#natural monopoly

Text

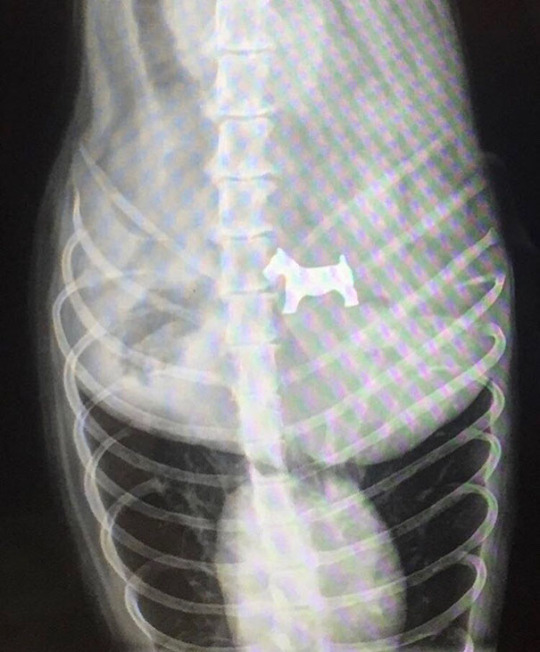

This dog accidentally swallowed the dog piece from monopoly.

#interesting#interesting facts#nature is everything#nature is weird#nature#discover#thats interesting#thats insane#thats incredible#animals#dogs#dog#monopoly#dog safety#dogs are family#dogs are the best#dogs are weird#dogs are better than people#dogs are great#dogs are amazing#dogs are awesome#what the hell#what the fuck#x ray#xray#what the heck#what then#what the flip#what the fuuuuuuuuck#what the shit

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

oh btw. Goats and sheep may be an illustration of God separating His flock from everyone else, but like. If u make a character with horns that doesn't inherently make them a demon or demon adjacent. Yeah somebody invented horns and it certainly wasn't the devil!

#tm speaks#text post#we talk a lot about not letting pagans have a monopoly on natural imagery and guess what. horns are a part of that#'this character has horns so they're probably a demon' my brother in Christ who do you think made horns in the first place#this is one of those things im training myself about so u get a post on it#christianity#like obv there WILL be demon characters out there with horns but horns do not immediately mean demons

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

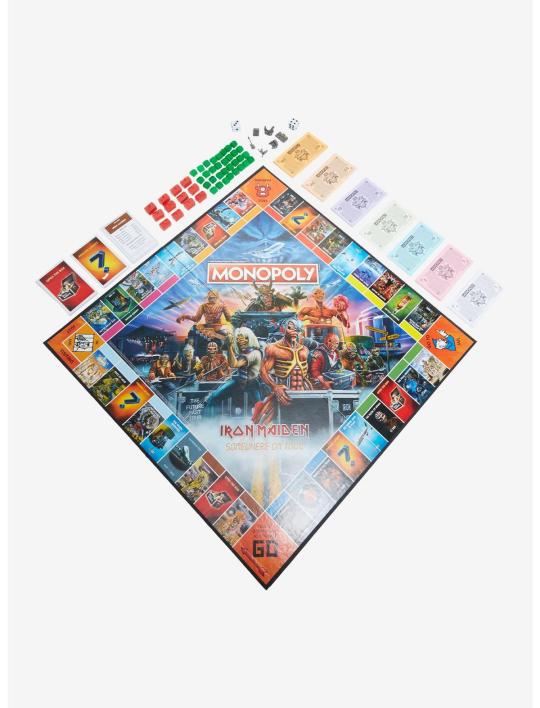

no fucking way

#that is so stupid that is so so stupid.#naturally i kind of want it but not for 50 fucking dollars. THIS IS SO STUPID A BAND IS A TERRIBLE BASIS FOR A MONOPOLY GAME...

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

i hate power companies i hate power companies i hate power companies

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Favorite PolSci paper?

...you should really know not to expect anything resembling concision from me, my friend.

So, uh...I'm not even gonna try to pick one.

The thing about me and political science is that I skew a lot closer to the humanities end of the analytical pool; I tend to be more inductive than deductive and it shows. I also tend to be skeptical of most work's explanatory power, and extremely skeptical about anything claiming predictive power. My favorite work tends to incorporate historical research and ethnographic data, and I tend enjoy critique papers and theory building. I tend to like "mid-level" approaches, where people try to study a specific phenomenon rather than going for large unifying theoretical questions, because I favor smaller knowledge claims with more data behind them. It's harder to build than tear down, and unfortunately I just love "tearing down" work. That said, there are some things that are really hard to research, and I'm always impressed by scholars who manage to do it well, either by spending a lot of time building trust or else by thinking of novel measures.

Kathleen Collins has a neat paper that tries to understand something really dang hard to research: banned underground movements in Central Asia. It's called "Ideas, Networks, and Islamist Movements: Evidence from Central Asia and the Caucasus." Specifically, she's looking at the spread of social movements that politicize Islam, and why they might succeed and take root in the face of governmental opposition or fail.

What I like in particular about the piece (in addition to the interview data she managed to collect from people involved in very illegal movements in generally illiberal states) is that she proposes mechanisms for the spread of a particular ideology in the face of state repression rather than just assuming "well, it's an Ideology! It's powerful!" She looks specifically at ideational fit and recruitment/idea networks (i.e. how the word is spread), and whether they're inclusive or exclusive networks (more about the "not us" or more about "join together").

It's ultimately case study research, but unlike a lot of case studies, convenience is decidedly not a driving factor behind her particular cases because she picked one of the hardest things to get people to talk about outside of a war zone. And of course, she gains a lot of respect from me by realistically assessing the implications for her paper (nothing turns me into a shark faster than people claiming greater explanatory power than their paper actually provides). So. Great insights, she really interrogates the mechanisms she proposes (which is absolutely what you have to do if you're theory-building with case studies), and she incorporates both extensive interviews from focus groups, political leaders, and surveys.

There's a series of pieces about Euromaidan by Volodymyr Ishchenko that I really enjoyed. The first is more or less introducing a database recording Euromaidan protest events that I admire. It does a good job being thorough and controlling for common biases from databases made up of media reports (skews towards big cities, sensationalist events, etc). I'm impressed by the dataset, and find the analysis particularly interesting.

Ishchenko really digs into what Euromaidan looked like on the ground and how it manifested regionally, who was involved, and what happened at protests. A bunch of scholars were going back and forth on whether Euromaidan was actually violent or not or what the degree of state involvement was, but he pretty convincingly argues that most of these arguments are based on...well, not cherry-picked exactly, but non-comprehensive evidence.

So you get one person who is saying stuff like "it was totally organized violence" and another saying "it was totally peaceful and state-escalated" and "it was mostly organized by the far-right" and "it was totally a popular protest" and frankly, based on their evidence, none of those contradicting claims were wrong because nobody was comprehensively analyzing what actually happened in all the protests and paying specific attention to who, what, where, and when incidents happened.

So he argues that most protests were peaceful, but there are specific regional trends, and eastern protests tended to be much less popular but had a higher concentration of far-right organizers, which is why some people can honestly say it was like a coup while a lot of other people can say "it was just a popular protest." He also identifies who exactly was involved, and when, and where, which is really important; in a followup article, Ishchenko IDs the groups with the resources to "[initiate] and [diffuse] efficient, coordinated, and strategic violence" and talks about how when Euromaidan was violent &/or radicalized, who was involved, and why. So who specifically was involved, who had organizational knowledge and violent knowledge, and when/where were they involved?

The concept of violent organization or escalation to violence is really interesting because people tend to separate peaceful from violent organization like they're two separate phenomenons or people assume that violent stuff was always going to be violent (scholars of violence are especially prone to only studying events where violence occurred, and when you want to know why something happens, it's really really important to look at why it might not happen). So I like what Ishchenko does.

My appreciation for Ischenko comes largely from a neat article by Charles King called "The Politics of Microviolence" which makes the assertion I just mentioned about violent and non-violent events being part of the same phenomenon. His piece is mostly a critique of the literature that then highlights two papers doing it well. (he argues we need to think smaller instead of only looking at large-scale violent events, and we need to consider when violence doesn't happen when it could have).

Oh man, there's a lot of really good work that I'm leaving out. Most of it is on civil war, paramilitaries and militias, and socialization to participate in violence (there's a really interesting study that says we basically assume it's easy to get people to be violent, then says that's not necessarily the case because that socialization fails, then works with with Israeli defectors). But my list kept growing and so I'll stop here.

The challenge with all scholarly work is that the more specialized you get, the easier it is to get siloed and unfortunately, it does get easier to take methodological assumptions as facts. For all the buzz around interdisciplinary stuff, there is a reason people specialize. I tend to be a connection-minded person and so I eat up work that combines disciplines well or critiques methodological assumptions that put two things into stark categories. But there's often a pretty good reason why those categories develop. Thus is the nature of scholarship...

Bibliography

Collins, Kathleen. 2007. "Ideas, Networks, and Islamist Movements: Evidence from Central Asia and the Caucasus." World Politics; World Pol 60 (1): 64-96. doi:10.1353/wp.0.0002.

Ishchenko, Volodymyr. 2016. "Far Right Participation in the Ukrainian Maidan Protests: An Attempt of Systematic Estimation." European Politics and Society (Abingdon, England) 17 (4): 453-472. doi:10.1080/23745118.2016.1154646.

Ishchenko, Volodymyr. 2020. "Insufficiently Diverse: The Problem of Nonviolent Leverage and Radicalization of Ukraine’s Maidan Uprising, 2013–2014." Journal of Eurasian Studies 11 (2): 201-215. doi:10.1177/1879366520928363. https://doi.org/10.1177/1879366520928363.

King, Charles. 2004. "The Micropolitics of Social Violence." World Politics; World Pol 56 (3): 431-455. doi:10.1353/wp.2004.0016.

#none of this is even getting into my big critique of a lot of literature#which is that i was trained in a field that just loves states#which means a lot of people i know about who study violence are asking it from the field of security#and security is about the security of the state#so it divides people pretty starkly based on their pro- or anti-government affiliation#and i'm not satisfied with that analysis#idk it's kinda like what volkov says in violent entreprenuers: we draw a line between organized crime and legitimate business#like there's a fundamental difference between state-sanctioned economic activity and state-criminalized economic activity#or state-sanctioned violence and non-state-sanctioned violence#and i don't think two types of the same behavior are fundamentally different just because they where they operate vis-a-vis the state#same thing with violence. who's to say the natural state of violence is that the state has a monopoly on it?#specifically. i think it's wrong and ahistorical to assume it's an anomaly when non-state actors engage in violence#even organized violence.#so yeah...i do think there's a difference between paramilitaries like SWAT and many militias#but rebel groups and state-aligned militias? not so much. or at least that's my current hypothesis based on what i've read#would like to do more research but alas. that's hard and i'm not willing to go for a phd in the foreseeable future#asks

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

I made a chess monopoly because I was 1) Bored and 2) inspired by the silly monopoly variants that already exist this is what it looks like

#chess#monopoly#if anyone has any ideas for calculation / natural language advice cards i would love to hear them#so far i only have like 6#calculation can be bad but NLA is always good

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

wut

#so apparently yt ppl on tiktok r now trying to callout a filipino woman being able to get a tan#like they’re saying she’s blackfishing cause she’s darker than usual when the thing is that she just got some sun#this is just a hairbrained theory but r these yt ppl like trying to like standardize race or something#like either last year or the start of this year u saw yt ppl accuse black ppl with natural narrow eyes of asianfishing#(its also worth noting that they especially did this to black girls with like cutesy aesthetics)#and then they started calling any attractive person of color white passing#like r they saying that black ppl have a monopoly on dark skin#and asians have a monopoly on narrow eyes#and yt ppl have a monopoly on attractiveness#i feel like the whole asianfishing accusations towards black women with cutesy aesthetics supports this#like they’re trying (and failing) to box blackness into whatever their conception of the hood is#and they’re beyond obvious in revealing that they think of asians purely through a fetishized lens of anime and k pop waifus

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Apulia my love...

The town of Monopoli

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

it never ceases to amaze me how capital just steals and steals and steals from the commons. capitalism robs humanity of its progress, every step of the way, and then has the gall to ascribe progress to themselves.

#thinking about my brainrot for all making but also reading about the Open Library#the ability for everyone EVERYWHERE to access knowledge and texts#for people in war torn countries to get an education! to be part of humanity!#BLOCKED by a bunch of corporations who just want more money and more monopoly off the earth#its disgusting its against human nature#idk if its just me but those contradictions Marxist say are the basis of revolution? clearer every damn day

1 note

·

View note

Text

I Am a LIFE

I am life, I have purpose in life

I am a purpose in life

Everyone is

Life I am

Purpose I have of life

Everyone has

All ones feel

The calling

Others just non stirring

Can’t change those against LIFE

They are here in the now

Present life being in the tolerable world

The problems are everywhere

What can one really do!

Don’t like reference of ONE

what would you do ?

Not even capitalized

It’s One that just has this LIFE

It’s all for everyone

You mean something

You have Energy

Just like in variables like everyday

You have skills attributes

Meaning to the whole of this Planet

Energy positive is better

I am a Life

My Energy 4

#wordsbymm#natural view#natural views#photobymm#photographybymm#early morning#pay attention#clouds#wrapbymm#picb4dinner#MMybsDroW#Living infinitely forever energy#LIFE#in ads a monopoly#saw them all day#taking money and some government#& body counts#WCNSF#and Hostages still taken#How are Ukrainians#those other people#still threatened by those#and what about thee#are the so and so still surviving#they like in Ukraine#Gaza may still be under rubble#Unlike Putin#But Still Damaging like a Putin#it was the tunnel varmin#we such theoretic rethink still doing nothing

0 notes

Text

also only tangentially related but it never ceases to amaze me how the internet, as both a space and an infrastructure, is largely a US property. like we're all just guests and tenants here. with that in mind it really isn't a wonder why a lot of usamericans, in general, tend to have difficulties conceptualising that the rest of the world exist. it's not just about the numbers, nor is it the language. it's kinda just hard ig to imagine other neighbourhood existing when, ostensibly, there isn't any.

also that kinda makes tiktok also p amazing in its own right. like yea it's bad for multitudes of things but looking at the mega-platforms that exist today?? am p sure it's literally the only one that's neither us-based nor us-owned. like that's mad wild.

#but yea expanding on the ''neighbourhood'' thing it really just goes like#the internet isn't just prioritising english-speakers (which would naturally mostly come from us first then canada/uk second)#the whole infrastructure was quite literally built with them and only them in mind.#it's more than catering to them it's basically existing *for* them#we're all afterthoughts here and once the infrastructure was occupied by us-based/owned companies that became monopoly conglomerates#it was truthfully over for us i think#like we're standing on other people's lands and quite a number of them are hostile to us yet to build another land is near impossible#if not purely a waste of resource. so ... what now?

0 notes

Text

So you're telling me that Scar naturally got the permit for sand, giving him the coveted monopoly, and didn't even want it anymore, whereas Grian has wound up with the permit for red sand and does actually want to use it. Red sand. Red. Meanwhile the end of third life involved Grian killing Scar and staining the sand with his blood following a conflict fuelled by a hopeless monopoly. And it's still following them years after the actual murder. And I'm supposed to be normal about this how exactly

#i love you coincidence i love you random parallels i love you confirmation bias#trafficblr#life series#life series smp#elfy talks#grian#mcyt#goodtimeswithscar#third life#3rd life#desert duo#hermitcraft#hermitcraft season 10

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

The majority of censorship is self-censorship

I'm on tour with my new novel The Bezzle! Catch me TONIGHT in SAN DIEGO (Feb 22, Mysterious Galaxy). After that, it's LA (Saturday night, with Adam Conover), Seattle (Monday, with Neal Stephenson), then Portland, Phoenix and more!

I know a lot of polymaths, but Ada Palmer takes the cake: brilliant science fiction writer, brilliant historian, brilliant librettist, brilliant singer, and then some:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/02/10/monopoly-begets-monopoly/#terra-ignota

Palmer is a friend and a colleague. In 2018, she, Adrian Johns and I collaborated on "Censorship, Information Control, & Information Revolutions from Printing Press to Internet," a series of grad seminars at the U Chicago History department (where Ada is a tenured prof, specializing in the Inquisition and Renaissance forbidden knowledge):

https://ifk.uchicago.edu/research/faculty-fellow-projects/censorship-information-control-information-revolutions-from-printing-press/

The project had its origins in a party game that Ada and I used to play at SF conventions: Ada would describe a way that the Inquisitions' censors attacked the printing press, and I'd find an extremely parallel maneuver from governments, the entertainment industry or other entities from the much more recent history of internet censorship battles.

With the seminars, we took it to the next level. Each 3h long session featured a roster of speakers from many disciplines, explaining everything from how encryption works to how white nationalists who were radicalized in Vietnam formed an armored-car robbery gang to finance modems and Apple ][+s to link up neo-Nazis across the USA.

We borrowed the structure of these sessions from science fiction conventions, home to a very specific kind of panel that doesn't always work, but when it does, it's fantastic. It was a natural choice: after all, Ada and I know each other through science fiction.

Even if you're not an sf person, you've probably heard of the Hugo Awards, the most prestigious awards in the field, voted on each year by attendees of the annual World Science Fiction Convention (Worldcon). And even if you're not an sf fan, you might have heard about a scandal involving the Hugo Awards, which were held last year in China, a first:

https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/science-fiction-authors-excluded-hugo-awards-china-rcna139134

A little background: each year's Worldcon is run by a committee of volunteers. These volunteers put together bids to host the Worldcon, and canvass Worldcon attendees to vote in favor of their bid. For many years, a group of Chinese fans attempted to field a successful bid to host a Worldcon, and, eventually, they won.

At the time, there were many concerns: about traveling to a country with a poor human rights record and a reputation for censorship, and about the logistics of customary Worldcon attendees getting visas. During this debate, many international fans pointed to the poor human rights record in the USA (which has hosted the vast majority of Worldcons since their inception), and the absolute ghastly rigmarole the US government subjects many foreign visitors to when they seek visas to come to the US for conventions.

Whatever side of this debate you came down on, it couldn't be denied that the Chinese Worldcon rang a lot of alarm-bells. Communications were spotty, and then the con was unceremoniously rescheduled for months after the original scheduled date, without any good explanation. Rumors swirled of Chinese petty officials muscling their way into the con's administration.

But the real alarm bells started clanging after the Hugo Award ceremony. Normally, after the Hugos are given out, attendees are given paper handouts tallying the nominations and votes, and those numbers are also simultaneously published online. Technically, the Hugo committee has a grace period of some weeks before this data must be published, but at every Worldcon I've attended over the past 30+ years, I left the Hugos with a data-sheet in my hand.

Then, in early December, at the very last moment, the Hugo committee released its data – and all hell broke loose. Numerous, acclaimed works had been unilaterally "disqualified" from the ballot. Many of these were written by writers from the Chinese diaspora, but some works – like an episode of Neil Gaiman's Sandman – were seemingly unconnected to any national considerations.

Readers and writers erupted in outrage, demanding to know what had happened. The Hugo administrators – Americans and Canadians who'd volunteered in those roles for many years and were widely viewed as being members in good standing of the community – were either silent or responded with rude and insulting remarks. One thing they didn't do was explain themselves.

The absence of facts left a void that rumors and speculation rushed in to fill. Stories of Chinese official censorship swirled online, and along with them, a kind of I-told-you-so: China should never have been home to a Worldcon, the country's authoritarian national politics are fundamentally incompatible with a literary festival.

As the outrage mounted and the scandal breached from the confines of science fiction fans and writers to the wider world, more details kept emerging. A damning set of internal leaks revealed that it was those long-serving American and Canadian volunteers who decided to censor the ballot. They did so out of a vague sense that the Chinese state would visit some unspecified sanction on the con if politically unpalatable works appeared on the Hugo ballot. Incredibly, they even compiled clumsy dossiers on nominees, disqualifying one nominee out of a mistaken belief that he had once visited Tibet (it was actually Nepal).

There's no evidence that the Chinese state asked these people to do this. Likewise, it wasn't pressure from the Chinese state that caused them to throw out hundreds of ballots cast by Chinese fans, whom they believed were voting for a "slate" of works (it's not clear if this is the case, but slate voting is permitted under Hugo rules).

All this has raised many questions about the future of the Hugo Awards, and the status of the awards that were given in China. There's widespread concern that Chinese fans involved with the con may face state retaliation due to the negative press that these shenanigans stirred up.

But there's also a lot of questions about censorship, and the nature of both state and private censorship, and the relationship between the two. These are questions that Ada is extremely well-poised to answer; indeed, they're the subject of her book-in-progress, entitled Why We Censor: from the Inquisition to the Internet.

In a magisterial essay for Reactor, Palmer stakes out her central thesis: "The majority of censorship is self-censorship, but the majority of self-censorship is intentionally cultivated by an outside power":

https://reactormag.com/tools-for-thinking-about-censorship/

States – even very powerful states – that wish to censor lack the resources to accomplish totalizing censorship of the sort depicted in Nineteen Eighty-Four. They can't go from house to house, searching every nook and cranny for copies of forbidden literature. The only way to kill an idea is to stop people from expressing it in the first place. Convincing people to censor themselves is, "dollar for dollar and man-hour for man-hour, much cheaper and more impactful than anything else a censorious regime can do."

Ada invokes examples modern and ancient, including from her own area of specialty, the Inquisition and its treatment of Gailileo. The Inquistions didn't set out to silence Galileo. If that had been its objective, it could have just assassinated him. This was cheap, easy and reliable! Instead, the Inquisition persecuted Galileo, in a very high-profile manner, making him and his ideas far more famous.

But this isn't some early example of Inquisitorial Streisand Effect. The point of persecuting Galileo was to convince Descartes to self-censor, which he did. He took his manuscript back from the publisher and cut the sections the Inquisition was likely to find offensive. It wasn't just Descartes: "thousands of other major thinkers of the time wrote differently, spoke differently, chose different projects, and passed different ideas on to the next century because they self-censored after the Galileo trial."

This is direct self-censorship, where people are frightened into silencing themselves. But there's another form of censorship, which Ada calls "middlemen censorship." That's when someone other than the government censors a work because they fear what the government would do if they didn't. Think of Scholastic's cowardly decision to pull inclusive, LGBTQ books out of its book fair selections even though no one had ordered them to do so:

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/05/06/books/scholastic-book-racism-maggie-tokuda-hall.html

This is a form of censorship outsourcing, and it "multiplies the manpower of a censorship system by the number of individuals within its power." The censoring body doesn't need to hire people to search everyone's houses for offensive books – it can frighten editors, publishers, distributors, booksellers and librarians into suppressing the books in the first place.

This outsourcing blurs the line between state and private surveillance. Think about comics. After a series of high-profile Congressional hearings about the supposed danger of comics to impressionable young minds, the comics industry undertook a regime of self-censorship, through which the private Comics Code Authority would vet comings for "dangerous" content before allowing its seal of approval to appear on the comics' covers. Distributors and retailers refused to carry books without a CCA stamp, so publishers refused to publish books unless they could get a CCA stamp.

The CCA was unaccountable, capricious – and racist. By the 60s and 70s, it became clear that comic about Black characters were subjected to much tighter scrutiny than comics featuring white heroes. The CCA would reject "a drop of sweat on the forehead of a Black astronaut as 'too graphic' since it 'could be mistaken for blood.'" Every comic that got sent back by the CCA meant long, brutal reworkings by writers and illustrators to get them past the censors.

The US government never censored heroes like Black Panther, but the chain of events that created the CCA "middleman censors" made sure that Black Panther appeared in far fewer comics starring Marvel's most prominent Black character. An analysis of censorship that tries to draw a line between private and public censorship would say that the government played no role in Black Panther's banishment to obscurity – but without Congressional action, Black Panther would never have faced censorship.

This is why attempts to cleanly divide public and private censorship always break down. Many people will tell you that when Twitter or Facebook blocks content they disagree with, that's not censorship, since censorship is government action, and these are private actors. What they mean is that Twitter and Facebook censorship doesn't violate the First Amendment, but it's perfectly possible to infringe on free speech without violating the US Constitution. What's more, if the government fails to prevent monopolization of our speech forums – like social media – and also declines to offer its own public speech forums that are bound to respect the First Amendment, we can end up with government choices that produce an environment in which some ideas are suppressed wherever they might find an audience – all without violating the Constitution:

https://locusmag.com/2020/01/cory-doctorow-inaction-is-a-form-of-action/

The great censorious regimes of the past – the USSR, the Inquisition – left behind vast troves of bureaucratic records, and these records are full of complaints about the censors' lack of resources. They didn't have the manpower, the office space, the money or the power to erase the ideas they were ordered to suppress. As Ada notes, "In the period that Spain’s Inquisition was wildly out of Rome’s control, the Roman Inquisition even printed manuals to guide its Inquisitors on how to bluff their way through pretending they were on top of what Spain was doing!"

Censors have always done – and still do – their work not by wielding power, but by projecting it. Even the most powerful state actors are not powerful enough to truly censor, in the sense of confiscating every work expressing an idea and punishing everyone who creates such a work. Instead, when they rely on self-censorship, both by individuals and by intermediaries. When censors act to block one work and not another, or when they punish one transgressor while another is free to speak, it's tempting to think that they are following some arcane ruleset that defines when enforcement is strict and when it's weak. But the truth is, they censor erratically because they are too weak to censor comprehensively.

Spectacular acts of censorship and punishment are a performance, "to change the way people act and think." Censors "seek out actions that can cause the maximum number of people to notice and feel their presence, with a minimum of expense and manpower."

The censor can only succeed by convincing us to do their work for them. That's why drawing a line between state censorship and private censorship is such a misleading exercise. Censorship is, and always has been, a public-private partnership.

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/02/22/self-censorship/#hugos

#pluralistic#ada palmer#worldcon#hugos#china#science fiction#fanac#publishing#censorship#systems of information control during information revolutions#scholarship

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

it’s really funny that taylor has adopted a reputation for being well-read and book smart because every time she opens her mouth about a real world issue i am forcibly reminded that she stopped going into school after 10th grade (her words), and even then, her formal education was provided by the state of tennessee.

because… what?

to frame patriarchy as this inherent thing that has ALWAYS existed and is as naturally occurring as a blue sky, is just not true. and to frame capitalism as this thing that is inherent is also just… not true. i could never unpack in just a post why those claims are ahistorical, but i will say that it is fucking nuts to look at an issue of capitalism and say “yeah it’s a problem, but, well, i’m just going to win at it 🤩” and call it feminism.

and that is the problem with white feminism. it just turns into idiots trying to speak on single topics and cherry pick their agendas, even though, in a sociopolitical or socioeconomic sense, it doesn’t work like that. you cannot talk about feminism without discussing western society, organized religion, global superpowers, communities of color, colonization, climate change, corporations, monopolies and more. anything less is useless at best and misleading at worst.

(because when you don’t, you get brain dead hot takes like “patriarchy has existed since the dawn of time, and so has money!”)

it’s like how greta thunberg said that she started as just a climate change activist, but now she’s basically a total anti-capitalist advocating for a complete disruption and overthrow to the way the world currently runs because she realized that advocating for that and advocating for climate justice are one and the same.

and if you criticize taylor swift for talking out of her ass, you’ll be hit with brainwashed swifties throwing out the word “misogyny” or “you’d never ask another celebrity this” or “you’re holding her to her own standards” because they’ve been hearing taylor’s bullshit feminism for so long that now they’ve adopted it as their own

taylor’s feminism will NEVER surpass the self-serving role it fills in her life because to do so would mean confronting the bigotry she has upheld, the questionable people she spends her time with, the wealth she is hoarding, her impact on the environment, and much more.

which is… fine, i guess. she doesn’t have to be a good feminist. but in that case she needs to pick a side and shut her fucking mouth about it. because letting her romp around spewing out the most egocentric and individualistic interpretations of it is boring and unhelpful.

#*#i knew that quote kept sticking out to me#like girl what the hell#taylor swift#time magazine#person of the year#white feminism

2K notes

·

View notes