#Feminist Press

Text

“An academic's institutional affiliations also afford greater access to media than lay feminists have. Professional journals print her studies. From there, her work may be picked up and disseminated by secondary media sources. Few outlets exist for non-academic papers (a fact especially striking when we consider the proportion of women each camp contains). Further, professionals can publish in both academic and movement journals; non-academics, only in the latter. Academic women also have access to the mass media proper (tv, radio, and newspaper coverage) via their institutional connections. Their views are solicited, their speeches noted, and their activities reported.

These university-based resources give academic feminists a disproportionate share in defining the movement. They exert undue influence on both ideological and structural matters.

First, academic feminists control certain communication channels between the movement and the target population. Their decisions on who gets to use which channels, and what sort of message is conveyed, affect the movement. For instance, they often receive requests for speakers. Matching audiences with "compatible" spokespeople, they determine which views are disseminated to which groups. ("I'll address the State House rally; I'm good at that. You talk to the Thursday night Great Books Club.") When special journal issues solicit their editorial advice, they divvy up work assignments the same way. Further, in their classes on women, they influence their students' views of the movement through their lectures, choice of required reading, and selection of guest speakers.

University funds help too. For example, conferences provide occasions for interaction both among movement members and the target population. Since academic institutions frequently subsidize conferences, university feminists influence the movement by establishing conference topics and format. Further, these same institutions pay honorariums to selected "lay" feminist speakers, so academics carry great weight in deciding which non-academics become movement spokeswomen.

Finally, with their media contacts and their credentals of expertise, academic feminists have a better crack at the target population than the "civilian" movement does. So they can legitimize their pre-eminence to the movement, by claiming special privileged communication with the masses. ('I talk with lots of people all over the country, and I know what reaches them.") They get away with this claim precisely because it's false. The communication flows only one way: they address the people, but the people have neither organizations, nor media, for formal means to reply. How can Jane Doe, average person, answer a newspaper series, radio marathon, or tv guest appearance? Academic feminists talk to, not with, the people. But their monopoly of communication channels makes it difficult for the movement to doubt, much less publicly dispute, their claim to represent the people.

Feminism’s new members have a lot of weight to swing around.”

- “Academic Feminists and the Women’s Movement” from Ain’t I a Woman?, vol. 4, no.1, April 1, 1974

#TELLLLLLL MEEEEEEE#who you thought of#for me it was the full surrogacy now woman#and mikki kendall though shes not an academic#and of course judith butler#feminist press

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

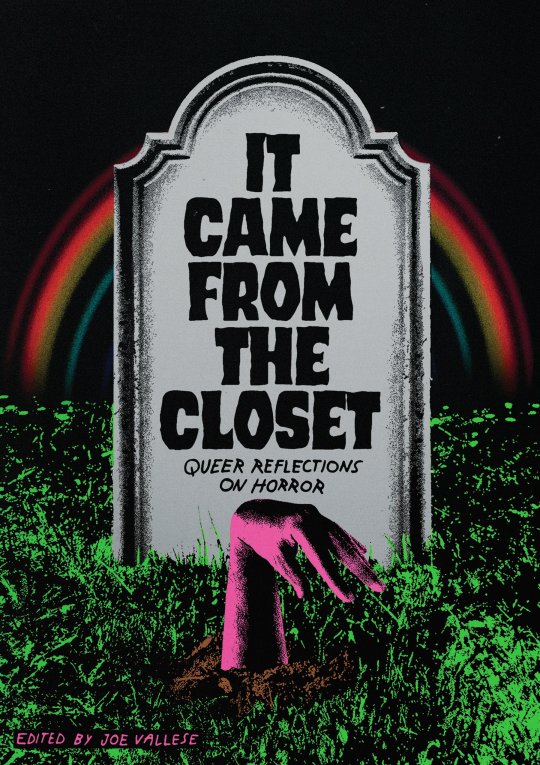

I am so honored and excited to have been included in It Came from the Closet: Queer Reflections on Horror.

Check out my essay, "Indescribable," in which I draw from my personal experience, as well as The Blob (1988) and Society (1989), to talk about gender and embodiment in relation to the figure of the blob monster.

#It Came from the Closet#Feminist Press#horror#queer horror#queer#LGBT#gender#essay#personal essay#film

16 notes

·

View notes

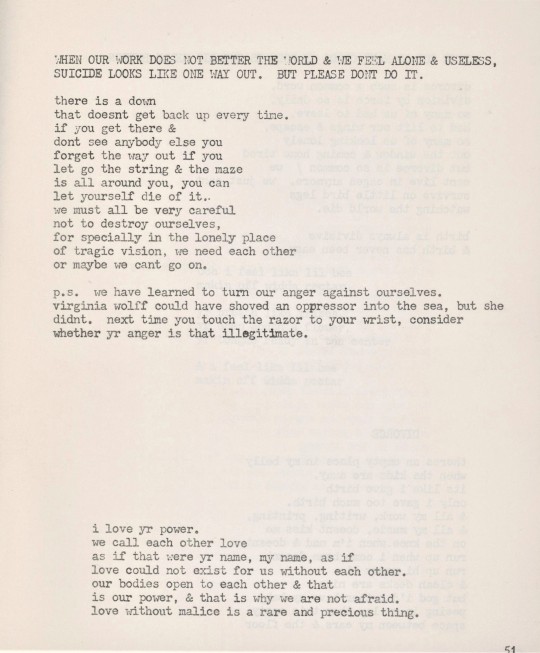

Photo

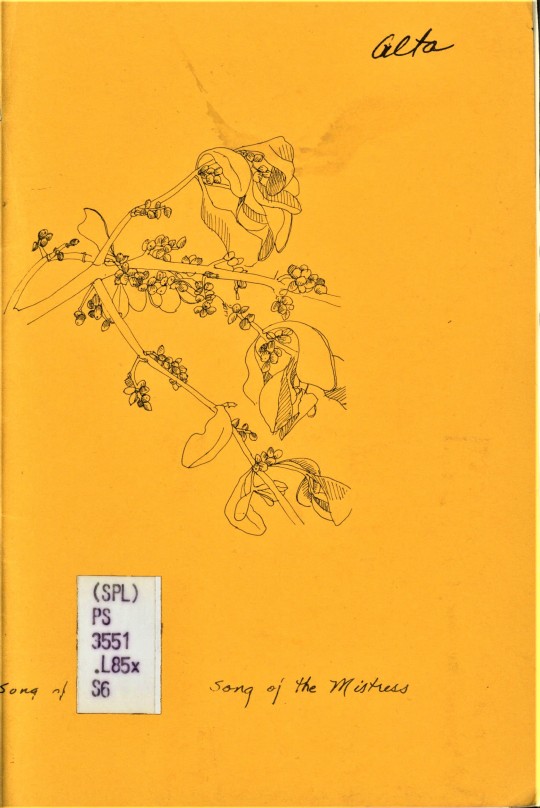

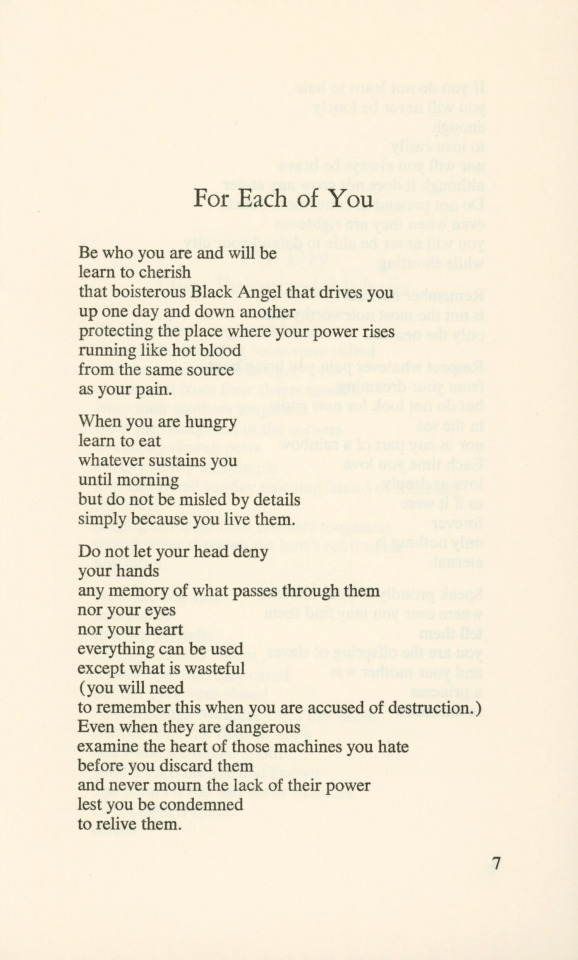

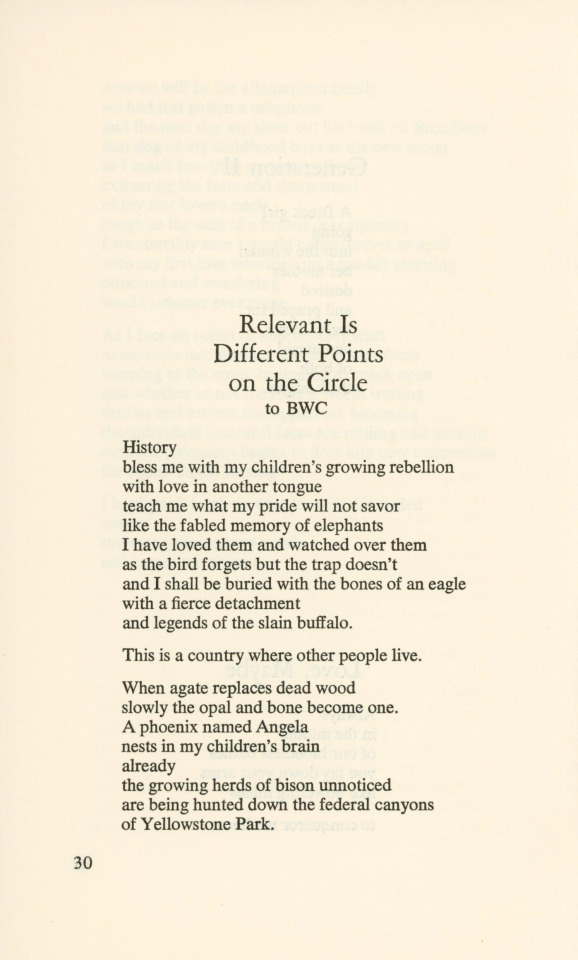

First Feminist Press!

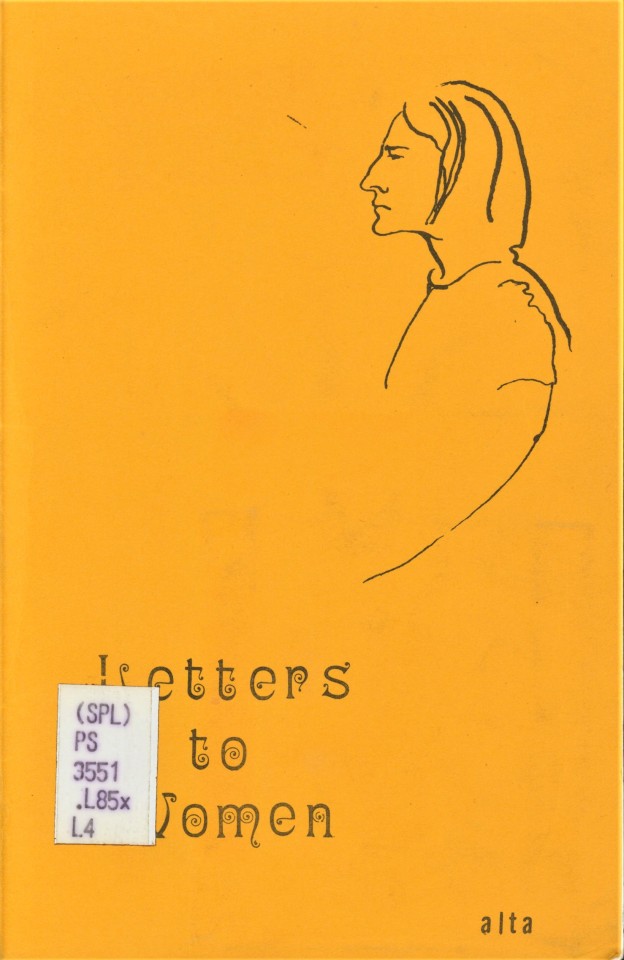

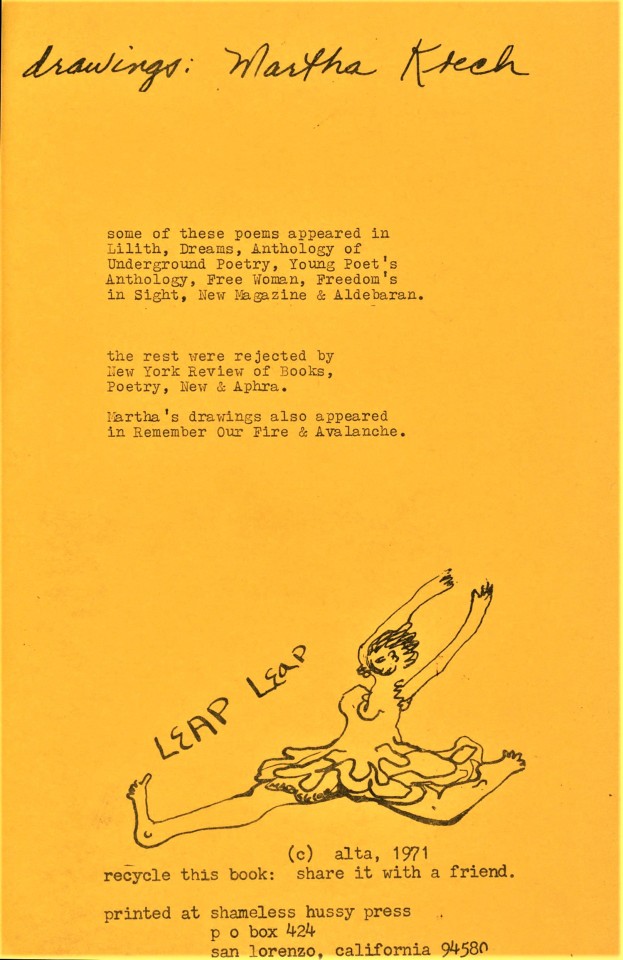

Shameless Hussy Press

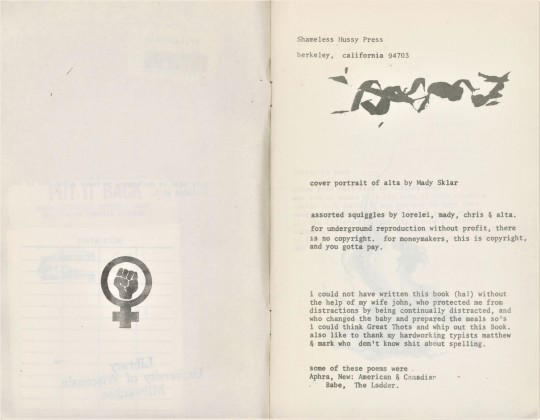

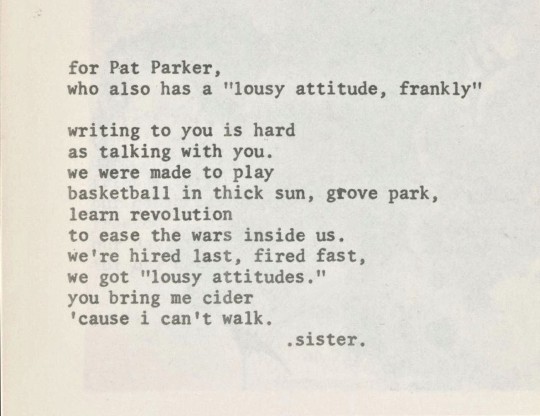

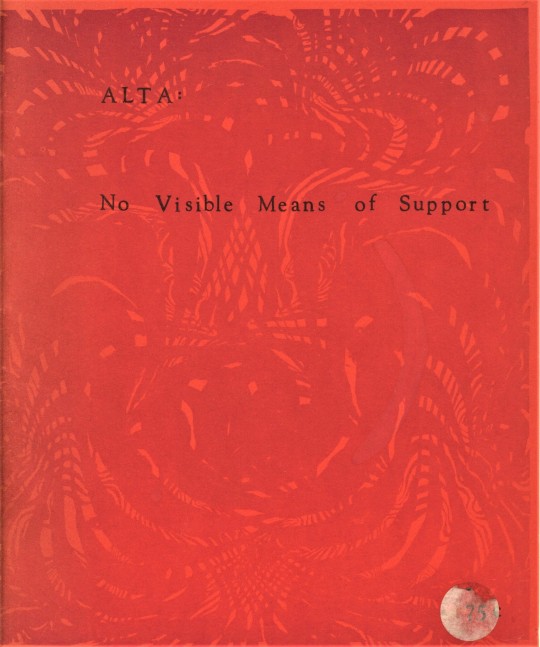

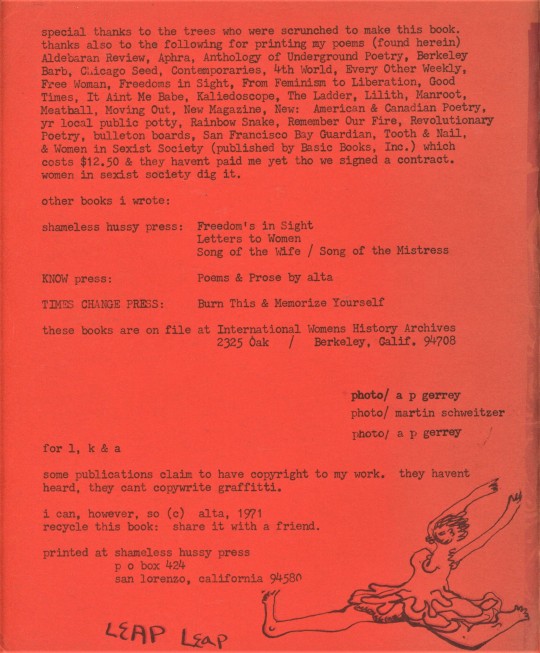

With the stress of Roe vs Wade potentially facing a repeal this summer, we want to let the women in our lives know they are not alone in their frustration. The fight women have been waging for their intellectual and bodily freedom has been a long one, so we wanted to revisit some history about the first women-owned feminist press in California, the Shameless Hussy Press! Poet and soon to be publisher Alta Gerrey founded the press in Oakland, California, in 1969, and would publish four women who later became prominent feminist writers: Pat Parker, Mitsuye Yamada, Ntozake Shange, and Susan Griffin. Alta published her own titles under her Shameless Hussy Press imprint, including three poetry collections preserved in our collection: Letters to Women, published around 1970; Song of the Wife; Song of the Mistress, published in 1971; No Visible Means of Support, published in 1971.

Alta’s sarcastic and straightforward writing style is reflected in the Shameless Hussy Press aesthetic. In her first collection, Letters to Women, she includes the iconic feminist symbol of a fist within the symbol of Venus and her copyright statement reads:

for underground reproduction without profit, there is no copyright. for moneymakers, this is copyright, and you gotta pay.

Alta emphasizes the aid of her friends and family in producing her book, and poetry aimed at letting women know that they were not alone in whatever injustices and hardships they faced, whether gender inequality and sexism, marriage and divorce, rape, mental illness, or raising children.

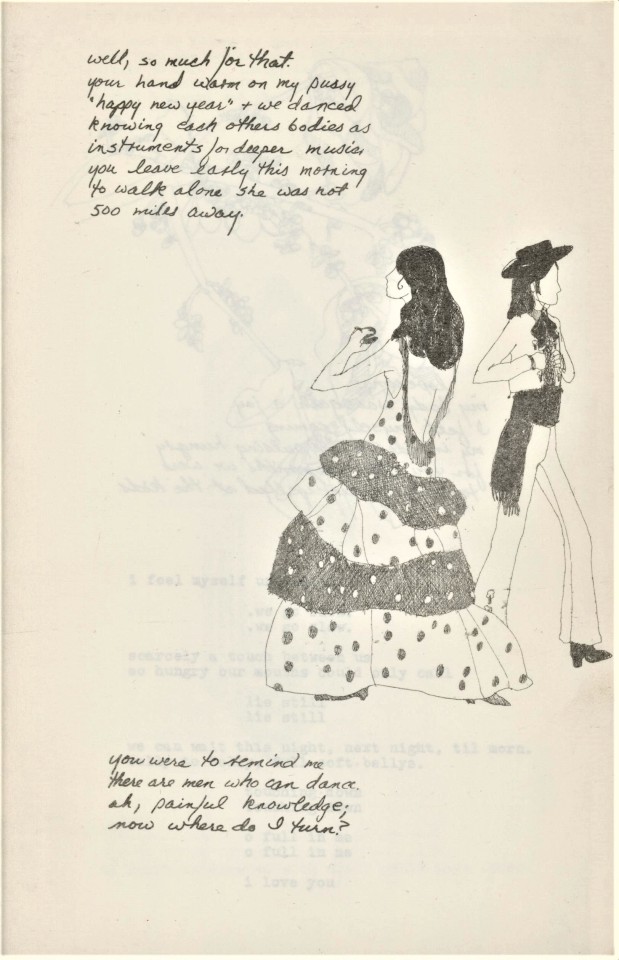

Alta’s second collection, Song of the Wife; Song of the Mistress, with drawings by Martha Kuech, reflects the intimacy the poet felt with her readers and how she used poetry as the outlet for emotions that could be a burden too heavy to carry at times. Letters to Women is dedicated “to every woman who is as isolated as i,” but Song of the Wife; Song of the Mistress "isn’t dedicated to anybody. eat yr hearts out.” Alta had a love for improper grammar, punctuation, and unconventional spelling. The first half of this second book reproduces a handwritten cursive script, presumably Alta’s handwriting, and the second half switches back to typewriter print. This title and Alta’s third collection, No Visible Means of Support, were both published after the Shameless Hussy Press had moved down the Bay to San Lorenzo, California, from its original location in Berkeley. Alta made the choice to move her independent press after the sabotage of a friend’s press in the same area, as well as to protect her daughter and herself from death threats she received for her work in the lesbian, feminist, and activist communities.

Shameless Hussy Press was the first to publish Ntozake’s Shange’s poetic performance work, For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow Is Enuf, which was later adapted into an Obie award-winning Broadway theater production. In 1976, Shameless Hussy published Camp Notes and Other Poems by Mitsuye Yamada, revolving around her experiences in the internment camps and the pain she felt at being perceived as an outsider.

The formation of the Shameless Hussy Press by Alta and the Women’s Press Collective by Judy Grahn, with aid from Pat Parker (who I posted about earlier), was quite inspirational for second wave of feminism. The four women who brought the feminist and lesbian publishing community to the foreground in California, Alta, Susie Griffin, Judy Grahn, and Pat Parker, had all met originally as neighbors over tea, but decided it was time to take action in their communities. Alta said in an interview that the group would often argue over how political their writing should be, wondering whether they should, “stick to the personal. [but] Susie kept saying, ‘the personal is political.’”

Griffin’s works were said to have launched ecofeminism in the United States as she rose to become one of the most influential American feminist writers of the 20th century. Alta’s Shameless Hussy Press gave these influential women the opportunity to be published outside the patriarchy of mainstream publishing, allowing them to completely claim their work as their own. Shameless Hussy ran from 1969-1989, despite being a one-woman-publishing house, publishing over fifty titles in its 20-y3qr existence.

–Isabelle, Special Collections Undergraduate Writing Intern

#Shameless Hussy Press#Alta Gerrey#Alta#Letters to Women#Song of Wife ; Song of Mistress#No Visible Means of Support#Judy Grahn#Feminist Press#Lesbian Poetry#Women's Press Collective#Pat Parker#Susie Griffin#Ecofeminism#Martha Kuech#Ntozake Shange#For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow is Enuf#Mitsuye Yamada#Camp Notes and Other Poems#Second Wave Feminism#Isabelle

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

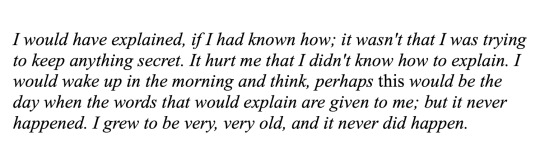

— Suzette Haden Elgin; Native Tongue

[Photo ID: "I would have explained, if I had known how; it wasn't that I was trying to keep anything secret. It hurt me that I didn't know how to explain. I would wake up in the morning and think, perhaps this would be the day when the words that would explain are given to me; but it never happened. I grew to be very, very old, and it never did happen." /END ID.]

#suzette haden elgin#native tongue#lexical gap#language#linguistics#science fiction#feminist fiction#feminist press#speculative fiction

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Welcome to Casablanca: Blood Feast by Malika Moustadraf

Welcome to Casablanca: Blood Feast by Malika Moustadraf @FeministPress @Read_WIT #WITMonth #ArabicLit

First, read the stories. Unsettling, allow them to assault your senses. Enter a world marred by poverty and illness, poisoned by the values of traditional patriarchal society, infused with everyday magic and superstition where women and men are trapped in roles defined by factors beyond their immediate control. This is the Casablanca of Malika Moustadraf’s fictional landscape, the space in which…

View On WordPress

#WITMonth#womenintranslation#Alice Guthrie#Arabic#Blood Feast#book review#books#Feminist Press#literature#Malika Mostadraf#Moroccan#short stories#Something Strange Like Hunger#translation

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I was trying to find some detail on the clearly small/feminist press that published Meanwhile Farm, Les Femmes, and finally I found a tidbit at the end of an NYT book review column from 1977 about current trends in publishing, but the whole last section is so fascinating I want to preserve it here:

Feminists. The success of Rita Mae Brown's “Rubyfruit Jungle” has focused new attention on the feminist tresses that have grown out of the women's movement over the last five years. An autobiographical novel that might do for lesbians what “A Catcher in the Rye” did for adolescence, “Rubyfruit” was first published in 1973 by Daughters Inc., a New York‐based company. The book went on to sell 70,000 copies without mass‐market distribution or major media attention, and then the paperback rights were sold to Bantam Books for $750,000.

That sale makes Daughters one of the successful feminist presses; three others stopped publishing this year, leaving about 10 all over the country, some of which limit their activity to one or two poetry books a year. The tendency of feminist presses to adhere to a separatist ideology means that most will only employ feminist printers and distributors (one of the latter, Women in Distribution [WIND1] in Washington, D. C., is beginning to penetrate the mass‐market paperback stores). Some of the presses have only just begun to employ fulltime sales representatives.

It is a struggle then, but here is a rundown of the main feminist presses, along with addresses where interested readers may write for lists of their books.

Daughters Inc. was founded in 1973 by Parke Bowman and June Arnold, who were interested primarily in feminist fiction. It has published novels by Selma Lagerlhf, Blance Boyd, Pat Burch, June Arnold, Bertha Harris, Monique Wittig, (22 Charles St., New York, N.Y.)

Diana Press is the first women's press to own its own paperback binding equipment, and when the purchase of a web press goes through next year it will he capable of printing mass market paperbacks hooks. It emphasizes elaborately prociticeu paperbacks, including its biggest success, Rita Mae Brown's “Songs to Handsome Woman,” a poetry collection that no one else would publish. “We have always tried to produce work by women who found it hardest to get accepted by publishers, among them Third World and lesbian women,” says Co'etta Reid, a founder. Diana later merged with Women's Press Collective, the first women's press. (4400 Market St., Oakland, Calif. 94608.)

Feminist Press started publishing out‐of‐print titles by women authors and now operates on the State University of New York campus at Old Westbury, where it receives free space in return for providing women's study courses and a women's history library. Because of its tax‐exempt status, Feminist Press's list resembles a university press, with titles like “Witches, Midwifes and Nurses,” a history of women in medicine. (Box 334, Old Westbury, N. Y. 11568.)

Les Femmes is a subsidiary of Celestial Arts, a male‐run general trade paperback house, and is looked down on by feminists as an opportunistic latecomer. The two‐year‐old house does, however, have several titles of practical interest for women. (231 Adrian Road, Millbrae Calif. 94030.)

Did I howl at the "Fake Feminist" accusations thrown at the last one? I sure did. ("who could be more Women than us. That's LITERALLY our name." / "Yeah I have some questions about that actually.")

#feminist press#i'm putting this in a general tag for interest but be warned there is literally nothing else like this on my blog

0 notes

Text

Currently Reading

Norman Erikson Pasaribu

HAPPY STORIES, MOSTLY

Translated from the Indonesian by Tiffany Tsao

#reading#Norman Erikson Pasaribu#Feminist Press#Tiffany Tsao#Indonesian writers#Indonesian literature

0 notes

Text

"The soil knows no border,

murmur their splintered feet."

— Claudia D. Hernández, "Knitting the Fog"

0 notes

Link

Naomi Kanakia is the author of two YA novels, with three more books in the works, including her first adult novel with Feminist Press (The Default World) and a nonfiction project with Princeton University Press (What’s So Great About The Great Books?, “a reexamination of the Great Books movement, and whether these much-criticized and much-praised works are worth reading if, like the author, you're not white, male, straight, and cisgender”). Naomi’s essays have been featured on Tablet, The Los Angeles Review of Books and Literary Hub, amongst others.

Topics include (breathe): working in “the highest of high culture (literary criticism) and in low culture (YA and sci-fi)”, idealising high culture only to discover “the majority of the writers, editors, agents, and critics involved simply don't have their own independent taste”, the reason why literary fiction doesn't discuss money, meritocracy, “the line between 'phony' and 'person with terrible taste'”, credibility, Azia Kim, impostors and con artists, being rejected, being celebrated, the demon of envy, being “a transfem brown YA writer who happens to write very good books”, the success of anti-racism and diversity efforts in the workplace, having fired and being fired by agents, the anti-woke movement, the lure of racial grievance and the fact “so many people only want to be seen as great, but they have no inner concept of what greatness entails.”

ENJOY.

#woke#anti woke#literary criticism#ya fiction#transfem#lgbtq+#Feminist Press#Princeton university press#nonfiction#Naomi Kanakia#longform#CRAZY LONG#crazy long longform

1 note

·

View note

Text

Andrew Scott at the National Board Of Review 2024 Awards Gala

131 notes

·

View notes

Text

#like cop the fuck on#barbie and Taylor swift is peak white feminism#it only takes a few brain cells to see that the Barbie movie is not the feminist holy grail that people think it is#like at all#not all cristicisms of Barbie or Taylor swift are sexist#because they are not representative of feminism or women as a whole#yes some criticisms are sexist but honestly so what? that’s not unique to these people that applies to all women#thinking that the issue on the forefront of the feminist movement is jokes about a movie is ridiculous#open your eyes!#it’s not even the most pressing issue in the west#palestine#free palestine#anti Zionist#anti zionism#barbie#Barbie movie#talyor swift#golden globes

106 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Academic feminists exercise great influence over the "civilian" movement. But there exists no semblance of a checks-and-balances system between the two groups. The movement did not elect academics to lead it; there was never a plebiscite; and there is no recall mechanism. Rather, their institutional affiliations give academics preeminence. So they must answer to only one constituency: their (mostly male, mostly hostile) colleagues.

Sometimes academic feminists do owe their jobs partly to movement ferment or women's caucuses' pressure. But the fact remains that the movement can neither reward nor punish them materially, once they are ensconced in their positions. It simply lacks the material wherewithal. And wielding what clout it has is difficult, since its loose structure hampers cohesive action. The professions on the other hand, enjoy both ample resources and the tight organization to use them deliberately. Consequently the movement cannot exert the leverage the professions can over academic feminists generally. The only realm in which it outweighs the professions is the moral realm; the only pressure point it can touch is individual conscience. And normally, alas, ethical judgements don't sway people who are padded by good salaries, lucrative grants, and the knowledge that their job futures depend more on their colleagues' good graces than on the movement's opinion. After all, academics get their credentials of expertise, their reputations, their jobs, and their security from their colleagues, not from the rag-tag movement. An academic woman may submit herself, voluntarily and individually, to the moral sanctions which constitute the movement's control over her. But academic women are formally and collectively responsible solely to the institutions which underwrite then: the universities.

“Academic Feminists and the Women’s Movement,” from Ain’t I a Woman?, vol. 4, no. 1, April 1974

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

radfem or any woman poll:

is there a specific age that you think pressure to wear makeup was at its highest? like do you think there's more pressure as you get older or more pressure when you're young?

(you can use ur best judgement to decide if you're qualified to answer-- in my experience most radfems on here are under 30 so we all only have so much life experience🤷♀️)

context (readings not necessary to vote): I'm 17 and so I'm highschool-aged although I've dropped out, but I still hang around highschool and college aged people and I genuinly cant imagine more pressure to wear makeup than right now. maybe it's j being a teenager ? or like idk hormones too?? but it feels indescribable and I've talked to my friends (and mom, see below) abt this and my friends also feel that sooooo much. which is maybe super self absorbed to think im at the age where its the worst so i could deffffinitely be way off. but do u think theres any relief as you get older? I talked to my mom about it and she does wear makeup, but she said something abt how it's nice to just be a "random non descript middle aged woman," and how that's kind of affected her own self image (in a good way). like she still feels the pressure to be beautiful, but maybe less so ? just curious what yall think!!

thanks yall.

#also fyi im not answering this poll ! im not doing the teenaged catagory and instead im j pressing the bottom choice#radical feminist safe#radical feminism#radblr#terfsafe#anti makeup#anti make up#anti beauty standards#anti beauty culture#anti beauty industry#question tag#radfem

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

International Women's Day

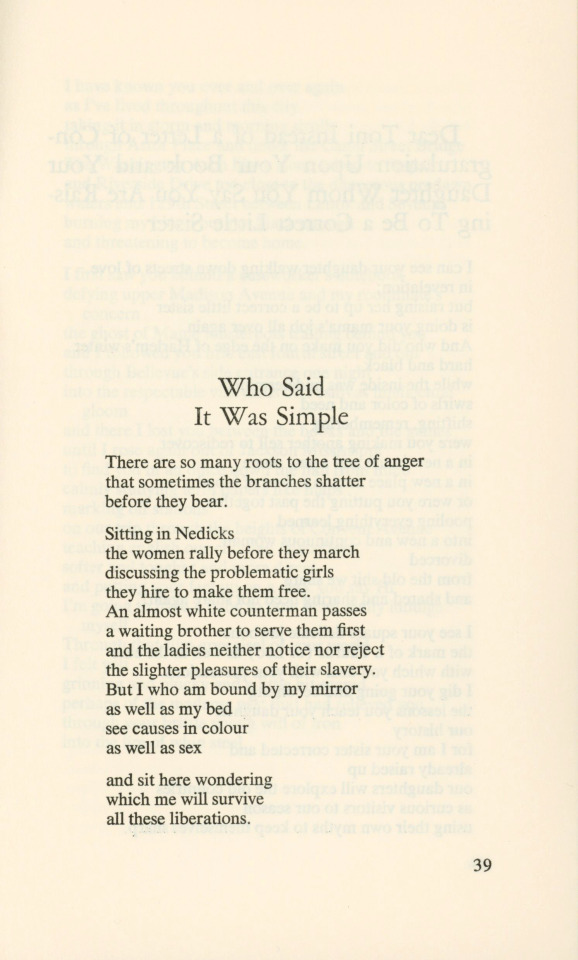

In celebration of Women’s History Month and International Women’s Day (March 8), we’re showcasing one of writer, educator, intersectional feminist, poet, civil rights activist, and former New York public school librarian Audre Lorde’s (1934–1992) early collections of poetry. From a Land Where Other People Live was published in 1973 by Detroit’s groundbreaking Broadside Press. This independent press was founded in 1965 by poet, University of Detroit librarian, and Detroit’s first poet laureate Dudley Randall (1914-2000) with the mission to publish the leading African American poetry of the time in a well-designed format that was also "accessible to the widest possible audience." A comprehensive catalog of Broadside Press’s impressive roster of artists (including Gwendolyn Brooks, Nikki Giovanni, and Alice Walker, to name a few), titled Broadside Authors and Artists: An Illustrated Biographical Directory, was published in 1974 by educator and fellow University of Detroit librarian Leaonead Pack Drain-Bailey (1906-1983).

Lorde described herself in an interview with Callaloo Literary Journal in 1990 as “a Black, Lesbian, Feminist, warrior, poet, mother doing [her] work”. She dedicated her life to “confronting and addressing injustices of racism, sexism, classism, and homophobia.” From a Land Where Other People Live is a powerfully intimate expression of her personal struggles with identity and her deeply rooted critiques of social injustice. The work was nominated for the National Book Award for poetry in 1974, the same year that Broadside Press published New York Head Shop and Museum, another volume of Lorde’s poetry featured in our collection. You can find more information on her writings and on the organization inspired by her life and work by visiting The Audre Lorde Project.

More posts on Broadside Press publications

More Women’s History Month posts

More International Women’s Day posts

-- Ana, Special Collections Graduate Fieldworker

#Women’s History Month#International Women’s Day#Audre Lorde#Broadside Press#Dudley Randall#Detroit#Poetry#From a Land Where Other People Live#Independent presses#Feminist writers#Lesbian writers#Black writers#women writers#women poets#Ana

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

— Suzette Haden-Elgin, Native Tongue

[Photo ID: ""Please," Nazareth said, giving up. "Please. I love you. And everything is going to be all right. Let that be enough." /End ID]

#suzette haden elgin#native tongue#science fiction#feminist fiction#feminism#feminist press#love#now reading#daymarkist

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

June Jordan, From Sea to Shining Sea [«Feminist Studies», Vol. 8, No. 3, Autumn, 1982; then in Living Room. New Poems, Thunder's Mouth Press, New York, NY, and Chicago, IL, 1985], in Home Girls. A Black Feminist Anthology, Edited by Barbara Smith, Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, NJ, 2000, pp. 215-221 [first edition Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press, 1983]

#graphic design#poetry#journal#book#june jordan#barbara smith#kitchen table women of color press#rutgers university press#feminist studies#1980s#2000s

67 notes

·

View notes