#anatomical venus

Text

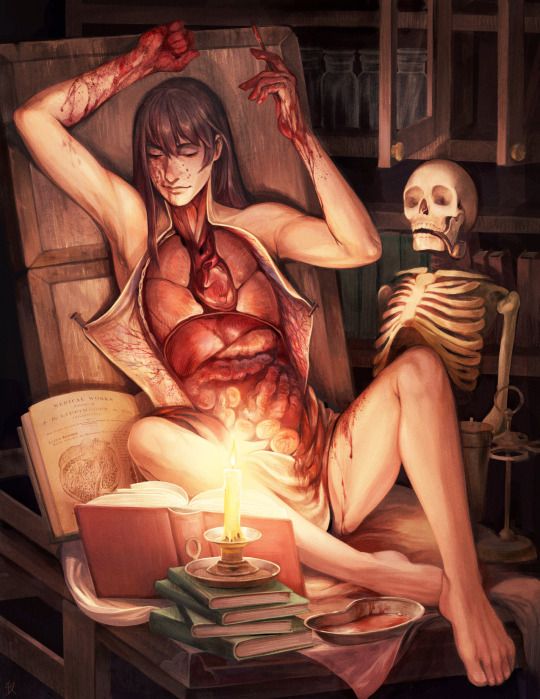

Anatomical Venus I

#ruineart#gore#blood#anatomical venus#illustration#horror#victorian medicine#something about baring oneself#surgery#a series#tw gore#cw gore#dissection#organs#autopsy#body horror#guro

13K notes

·

View notes

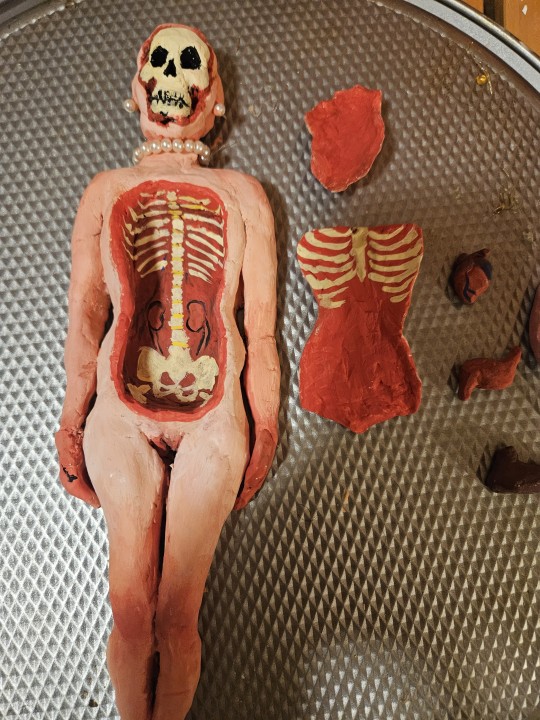

Text

Anatomical Venus update :) she's coming along quite well! The clay is very crumbly, obviously, as it is simply airdry. I want to do this with more permanent materials. She still needs hair, and a coat of sealant/varnish.

131 notes

·

View notes

Text

untitled by tali lennox, unknown date, oil on linen, unknown dimensions

237 notes

·

View notes

Text

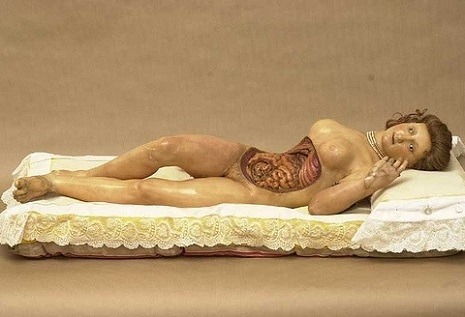

The anatomical waxes of La Specola in Florence

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy National Poetry Month 2024!

Happy National Poetry Month! Join us in celebrating by checking out these queer and/or trans poetry collections and novels in verse, and get even more recs by taking a gander at least year’s post!

Queer and Fearless: Poems Celebrating the Lives of LGBTQ+ Heroes by Rob Sanders and Harry Woodgate

Learn about the lives of some of the most important LGBTQ+ heroes in this unique picture book that…

View On WordPress

#Amber Dawn#Anatomical Venus#Bless the Blood#Brontez Purnell#Courtney Bates-Hardy#Franny Choi#jaye simpson#m. patchwork monoceros#Parisa Akhbari#Remedies for Chiron#Rev. Julián Jamaica Soto

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Anatomical Venus. Hand-embroidered artwork. 30" x 33"

youtube

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sketchbook nonsense.

Precious collected objects of curiosity.

(Preliminary sketchbook exploration for my huge Anatomical Venus silk scarf.)

#Anatomical Venus#anatomy#cabinet of curiosities#pinned specimens#illustration#art#sketchbook#watercolor

185 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Anatomical Venus, linogravure

Ces petites linogravures (20x5cm), tirées à la main sur papier machine et contrecollées sur canson 180g sont à vendre pour 5€ en main propre (Paris et IDF) ou 6,50€ par courrier en France métropolitaine !

Elles font de très bonnes petites décorations pour vos étagères et murs, ou de jolis marque-pages pour vos lectures du moment !

These small (20x5cm) hand-pulled linocuts, printed on printer paper and mounted on 180gsm paper are for sale for 5€ hand deliveery in and near Paris, or 6.50€ by mail in France. (DM to discuss shipping options in the EU if desired.)

They make lovely little trinkets for walls and cabinets, or original bookmarks !

Octobre 2022 — Zouabar

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

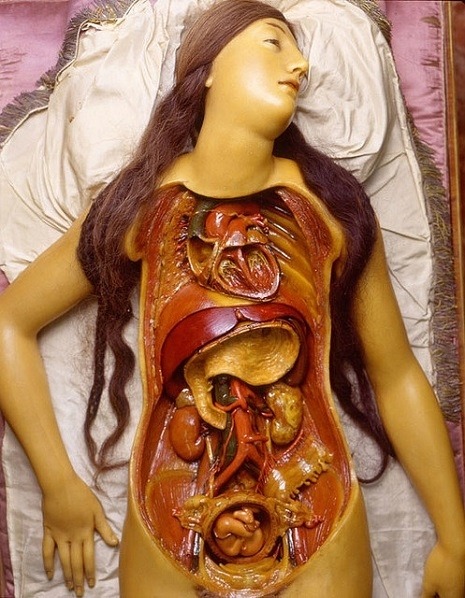

The Anatomical Venus

Between 1780 and 1782, Clemente Susini created the Anatomical Venus. She was conceived as a way to teach anatomy, cadavers being in short supply for reasons of medical ethics, rather than any shortage of death. Lifesize and made of wax, her prettiness is self-evident, and in case you missed it, adorned with a string of pearls. Her eyes are dead, unmistakably and her hair is real human hair. She is fashioned of seven anatomically correct layers, which the keen student can pull apart, ending in a teeny foetus curled in her womb.

It is genuinely difficult to pinpoint how unsettling it is, what an act of violence has been perpetrated by the accuracy of the rendering. There seems to be something blasphemous, inhumane, in creating a corpse and trying to beautify it – or rather, in considering beauty to be a necessary trait in an anatomically accurate dead body. In taking beauty to be such a critical component of womanhood, it misses, and seals in wax its own misapprehension of, what beauty is. Attractiveness and life are indivisible: there is nothing in natural life that is prettier dead than alive.

Necrophilia is a taboo for a reason. It is not what it says about, or does to, the corpse that makes it aberrant to desire it. It is what it says about your desire for women en masse, that you could see the appeal of a dead one: it is the logical end point of objectification, perceiving the physical traits to be so important that they continue to entice even after the life to which they were attached has been extinguished.

Joanna Ebenstein’s sumptuous and therefore even more disgusting book is fascinated by this era, in which “the study of nature was also the study of philosophy”; in which a body created for medical purposes could also be read as a work of art. Perhaps it is so horribly magnetic for purely anachronistic reasons: we are so used to the separation of body and mind, science and philosophy, that when we see that separation elided we cannot help but read in some insult to the spirit to see it reconnected with its own internal organs.

The aesthetics of anatomical drawings and models had been prized for some centuries before Demountable Venus, on the basis that, in order to be interested in the inner workings of the human body, men must be seduced by it. “Anatomy,” wrote Andreas Vesalius in 1543, “is an important part of natural philosophy; since it embraces the study of man and must properly be regarded as the prime foundation of the whole art of medicine and the source of everything that constitutes it.”

It is interesting to consider that the body – its nuts and bolts, the raw mechanics of it – had by this point long been considered a proper subject for artists. Leonardo da Vinci had dissected more than 100 bodies himself earlier that century, and a younger artist, Michelangelo Buonarroti, accepted a commission from a church for which he was paid in corpses.

Naturally, though, there is a piquancy to the female cadaver, not simply because of these hideously orgasmic expressions juxtaposed against intestines. It is a given that a woman’s body will be dismembered by life, and only by good fortune, put back together again. (The simplest for-instance: after a friend had a caesarian, her husband said, “I’ve seen a part of my wife no other man will ever see. Her kidneys.”)

In so many of these figures, almost all of them pregnant, the woman’s face is so idealised and the foetus so carefully rendered that she looks like the doll, and the baby like the human. The idea that beauty doesn’t simply cling on past the end of life, but is actually intensified by death, is explored by increments, so that Edgar Allan Poe’s contention that “the death of a beautiful woman is, unquestionably, the most poetical topic in the world” slips, tracelessly, into historian Philippe Aries’s, that “the dead body becomes in its turn an object of desire”.

The Anatomical Venus is literally uncanny, by Freud’s definition (borrowed from Schelling), “everything that was meant to remain secret and hidden has come into the open”.

https://www.google.com/amp/s/amp.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2016/may/17/anatomical-venus-anatomy-human-biology-joanna-ebenstein-books

103 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anatomical Venus III : Apotheosis

This is somewhat removed from the original anatomical inspiration. But this series represents a progression for me: a journey from the flesh, to the shedding of it. I hoped that within this labyrinth of veins, I would find divinity in repose.

#ruineart#illustration#anatomical venus#horroart#horror#veins#blood#wings#series#medical illustration

655 notes

·

View notes

Text

Milano

CERE ANATOMICHE

LA SPECOLA DI FIRENZE

DAVID CRONENBERG

David Cronenberg durante le riprese del film, Museo La Specola di Firenze. Foto Flavio Pescatori, Courtesy Fondazione Prada

24 Mar – 17 Lug 2023

“Cere anatomiche” è una mostra ideata in collaborazione con La Specola, parte del Museo di Storia Naturale e del Sistema Museale di Ateneo dell’Università di Firenze, e il regista e sceneggiatore canadese David Cronenberg.

Il progetto rappresenta una nuova tappa del percorso di ricerca attraverso il quale Fondazione Prada vuole far conoscere importanti collezioni provenienti da ‘musei ospiti’, per offrire interpretazioni inattese del patrimonio culturale e innescare un dialogo tra una collezione storica e un’istituzione contemporanea.

Creata nel 1775 e attualmente chiusa al pubblico per lavori di ristrutturazione della sua sede storica, La Specola è uno dei musei scientifici più antichi d’Europa. Al suo interno ospita più di 3,5 milioni di reperti animali, la raccolta più ampia al mondo di cere anatomiche del XVIII secolo e la collezione del ceroplasta siciliano Gaetano Giulio Zumbo (1656-1701). 1.400 elementi della straordinaria collezione di cere anatomiche sono stati realizzati tra la fine del XVIII e l’inizio del XIX secolo per ottenere un vero e proprio trattato didattico-scientifico che, senza bisogno di ricorrere all’osservazione diretta di un cadavere, si proponeva di illustrare l’anatomia del corpo umano.

“Cere anatomiche” si articola in due parti complementari. Una mostra riunisce tredici ceroplastiche del XVIII secolo provenienti dalla prestigiosa raccolta del museo fiorentino, e una serie di settantadue copie espositive di disegni anatomici raccolti in nove vetrine. In particolare, sono presentate quattro figure femminili distese, tra le quali una delle opere più importanti della collezione del museo La Specola, la cosiddetta Venere, un raro modello con parti scomponibili conosciuto per la sua bellezza.

Un inedito cortometraggio, realizzato da David Cronenberg negli spazi della Specola, introduce queste quattro cere in una dimensione alternativa, esplorando temi come la fascinazione per il corpo umano e le sue possibili mutazioni e contaminazioni. Il film di Cronenberg rivela la dimensione vitale e sorprendente delle ceroplastiche con l’obiettivo di generare una pluralità di nuove risposte emotive, suggestioni intellettuali e intense reazioni.

Come spiega David Cronenberg: “Le figure di cera della Specola furono create prima di tutto come strumento didattico, in grado di svelare i misteri del corpo umano a chi non poteva accedere alle rare lezioni anatomiche con veri cadaveri tenute nelle università e negli ospedali. Nel loro tentativo di creare delle figure intere parzialmente dissezionate, il cui linguaggio corporeo ed espressione facciale non mostrassero sofferenza o agonia e non suggerissero l’idea di torture, punizioni o interventi chirurgici, gli scultori finirono col produrre personaggi viventi apparentemente travolti dall’estasi. È stata questa sorprendente scelta stilistica che ha catturato la mia immaginazione: e se fosse stata la dissezione stessa a indurre quella tensione, quel rapimento quasi religioso?”

Il progetto si configura come un duplice intervento: la narrazione scientifica e quella artistica prendono forma in due allestimenti indipendenti realizzati dall’agenzia creativa Random Studio. Al primo piano del Podium le cere del museo La Specola sono esposte seguendo un rigoroso approccio museale. Al piano terra le stesse opere accedono all’immaginario del regista diventando le protagoniste di un enigmatico processo di metamorfosi.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tiny anatomical Venus embroidery

#embroidery#embroidery art#fiber art#black and white#black and white embroidery#embroidery aesthetic#hand stitching#yourgothicgranny#goth aesthetic#Rachel dreimiller#anatomy#anatomical illustration#anatomical venus

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Anatomical Venus (2022)

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

New Releases: April 9, 2024

Young Adult

Every Time You Hear That Song by Jenna Voris

They say to never meet your idols. But they never said anything about upending your life for a quest designed by one.

Seventeen-year-old aspiring journalist Darren Purchase has been a lifelong fan of country music legend Decklee Cassel, who’s as famous for her classic hits as she is for her partnership with songwriter Mickenlee Hooper. The…

View On WordPress

#A Sweet Sting of Salt#Anatomical Venus#Aubrey McFadden is Never Getting Married#Aurora Rey#Canto Contigo#Cedar McCloud#Courtney Bates-Hardy#Ellen van Neerven#Elliott Gish#Every Time You Hear That Song#featured#Georgia Beers#Good Bones#Grey Dog#Jenna Voris#Jonny Garza Villa#Kalie Holford#Katrina Carrasco#KT Hoffman#Nathan Burgoine#Party of Fools#Personal Score#Rose Sutherland#Rough Trade#The Final Curse of Ophelia Cray#The Prospects#Triad Magic

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the middle of one of the rooms of the Josephinum, laid out in a glass coffin like Snow White, is the figure of a beautiful nude woman. She lies on her back, in a pose suggesting intoxication or orgasm more than sleep: one knee slightly bent, hands rucking the silk sheets beneat her, her had tilted back in abandon or ecstasy. She has been slashed open from throat to groin. Her breasts hang to the sides, just flaps of wax, and her guts are a bulbous dark mass against her alabaster skin, coils of intestine resting on a pristine hip. On top of her long blonde hair, which spills prettily around her shoulders, is a delicate circlet of gold.

Next to her, in a similar glass and rosewood box, lies another lounging blonde figure, this one wearing a string of pearls. Her torso, too, is open, but not in the manner of a crime or an autopsy. The front of her torso has simply been sliced off in a neat, bloodless curve and deposited elsewhere. Instead of breasts, she has smooth expanses of light brown lung underneath her pearls. Under that, her diaphragm folds like a wing over her stomach and a neat tongue of pancreas. Something, maybe a kidney, lies by her side. Her eyes are open, and her expression is not exactly orgasmic; it is, more than anything, resigned. Tucked inside her pelvis is a fetus the size of a fist.

These are "anatomical Venuses", an eighteenth-century innovation in medical display: lovingly detailed wax models of ideal feminine beauties with real eyelashes and human hair and jewelry and abdomens full of gore. The Josephinum Venuses, and a number of other surviving Venuses of Europe, come out of the wax workshop of a Florentine museum: the Museum for Physics and Natural History, also known as La Specola. La Specola, like the Josephinum, is full of models depicting aspects of human anatomy -- "an encyclopedia of the human body in wax," as Joanna Ebenstein puts it in her lavishly photographed book The Anatomical Venus. Unlike dissection, wax was sanitary, odorless, and stable over a long period of time. It was also, potentially, beautiful. Wax models could be rendered placid and pain-free, their otherwise lovely faces and bodies drawing the mind away from death and towards higher (and lower) things. Like the Renaissance anatomical illustrations that preceded them, the La Specola waxworks were intended to show the hand of God in the human design. The luminous wax sculptures even called to mind earlier religious figurines. But they were also meant to be visually, even sexually, appealing. (This is why, despite the preponderence of male anatomical illustrations and models and cadaver dissections, there was no male equivalent of the Venus.) Ebenstein quotes eighteenth-century anatomical illustrator Arnaud-Éloi Gautier d'Agoty: "For men to be instructed, they must be seduced by aesthetics, but how can anyone render the image of death agreeable?" The anatomical Venus was the answer: the instructional realism of human innards, leavened by the seductive aesthetics of feminine beauty.

Zimmerman, Jess. Women and Other Monsters: Building a New Mythology. Beacon Press, 2021.

#jess zimmerman#women and other monsters#women and other monsters: building a new mythology#anatomical venus#excerpts#prose#nonfiction#*

3 notes

·

View notes