#brain pickings

Text

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Finding that vitalizing “a reciprocity between us perceiving the world together through art, and the world in turn reading us through what we make.”

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Superb_Owl Sunday article/photo gallery: "Gorgeous 19th-Century Illustrations of Owls and Ospreys" via The Marginalian (formerly Brain Pickings)

#owl#owls#osprey#ospreys#bird#birds#birds in art#Richard Lydekker#The Royal Natural History#natural history art#scientific illustration#book illustration#19th century#English art#European art#The Marginalian#Brain Pickings#article link#Superb Owl Sunday#animals in art

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

One of the hardest realizations in life, and one of the most liberating, is that our mothers are neither saints nor saviors — they are just people who, however messy or painful our childhood may have been, and however complicated the adult relationship, have loved us the best way they knew how, with the cards they were dealt and the tools they had.

It is a whole life’s work to accept this elemental fact, and a life’s triumph to accept it not with bitterness but with love.

How to make that liberating shift of perspective is what the playwright, suffragist, and psychologist Florida Scott-Maxwell (September 14, 1883–March 6, 1979) considers in a passage from her 1968 autobiography The Measure of My Days (public library).

She writes:

A mother’s love for her children, even her inability to let them be, is because she is under a painful law that the life that passed through her must be brought to fruition. Even when she swallows it whole she is only acting like any frightened mother cat eating its young to keep it safe.

In a sentiment that calls to mind Kahlil Gibran’s insight into the delicate balance of intimacy and independence essential for romantic love — which is always an echo of our formative attachments — she adds:

It is not easy to give closeness and freedom, safety plus danger.

(...)

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

A VERY GOOD READ FOR WRITERS OF *MEMOIR* (also my editorial speciality, visit cassandrapereira.com/editorial.)

"I recently found myself in an intense conversation with a friend about privacy — why it matters; how much of it we’re relinquishing and what for; whether it is even possible to maintain even a modicum of control over our own privacy at this point — the same intense conversation being had everywhere from family dinner tables to courtrooms to public radio to the highest levels of government.

It suddenly struck me that our cultural narrative about privacy is completely backward: What we really fear is not that the internet — or a prospective employer, or a nosy lover, or Big Brother — knows too much about us, but that it knows too little; that it fails to encompass Whitman’s multitudes which each of us contains; that it reduces the larger, complex truth of who we are to a few fragmented facts about what we do; that it hijacks our rich, ever-evolving personal stories and replaces them with disjointed anecdotal data.

Perhaps the most potent antidote to this increasingly disempowering cultural shift is to grow ever more thoughtful and deliberate about how we tell our own stories; to master the art of personal narrative so that we can write — writing being that most lucid mode of thinking and an indispensable form of talking to ourselves — about the expansive, dimensional, textured reality of who we are.

That’s what writer Vivian Gornick explores in the... 2001 classic The Situation and the Story: The Art of Personal Narrative (public library).

Gornick writes:

Every work of literature has both a situation and a story. The situation is the context or circumstance, sometimes the plot; the story is the emotional experience that preoccupies the writer: the insight, the wisdom, the thing one has come to say.

She begins by illustrating the power of personal narrative with, befittingly, a personal narrative:

A pioneering doctor died and a large number of people spoke at her memorial service. Repeatedly it was said by colleagues, patients, activists in health care reform that the doctor had been tough, humane, brilliant; stimulating and dominant; a stern teacher, a dynamite researcher, an astonishing listener. I sat among the silent mourners. Each speaker provoked in me a measure of thoughtfulness, sentiment, even regret, but only one among them — a doctor in her forties who had been trained by the dead woman — moved me to that melancholy evocation of world-and-self that makes a single person’s death feel large.

[...] The next morning I awakened to find myself sitting bolt upright in bed, the eulogy standing in the air before me like a composition. That was it, I realized. It had been composed. That is what had made the difference.

What made the eulogy so memorable, Gornick reflects, is precisely what lends personal narrative its power — a delicate mastery of structure, shapeliness, associative flow, and dramatic buildup. The way the younger doctor recounted coming of age under the influence of her departed mentor fused these essential elements of enchanting personal storytelling into what Gornick calls “narrative texture”:

The memory had acted as an organizing principle that determined the structure of her remarks. Structure had imposed order. Order made the sentences more shapely. Shapeliness increased the expressiveness of the language. Expressiveness deepened association. At last, a dramatic buildup occurred, one that had layered into it the descriptive feel of a young person’s apprenticeship, medical practices in a time of social change, and a divided attachment to a mentor who could bring herself only to correct, never to praise. This buildup is called texture. It was the texture that had stirred me; caused me to feel, with powerful immediacy, not only the actuality of the woman being remembered but — even more vividly — the presence of the one doing the remembering. The speaker’s effort to recall with exactness how things had been between herself and the dead woman — her open need to make sense of a strong but vexing relationship — had caused her to say so much that I became aware at last of all that was not being said; that which could never be said. I felt acutely the warm, painful inadequacy of human relations. This feeling resonated in me. It was the resonance that had lingered on, exactly as it does when the last page is turned of a book that reaches the heart.

Illustration from ‘The Jacket.’ Click image for details.

This ability, Gornick argues, requires a certain sensitivity to the mystery of personal identity over time, a certain intimacy with the stable of our former selves. She writes:

It was the act of imagining herself as she had once been that enriched her syntax and extended not only her images but the coherent flow of association that led directly into the task at hand.

It requires, too, a clarity of purpose and a discernment in choosing from among one’s multitudes only those selves that add texture to this particular story:

The speaker never lost sight of why she was speaking — or, perhaps more important, of who was speaking. Of the various selves at her disposal (she was, after all, many people — a daughter, a lover, a bird-watcher, a New Yorker), she knew and didn’t forget that the only proper self to invoke was the one that had been apprenticed. That was the self in whom this story resided. A self — now here was a curiosity — that never lost interest in its own animated existence at the same time that it lived only to eulogize the dead doctor. This last, I thought, was crucial: the element most responsible for the striking clarity of intent the eulogy had demonstrated. Because the narrator knew who was speaking, she always knew why she was speaking.

And so does Gornick — she recounts this anecdote with the clear purpose of adding dimension to the inquiry at the heart of her book, which deals with that immensely intricate art of writing about oneself not from the surface stream of solipsism or narcissism but from a deeper well of universal truth. More than a decade later, Cheryl Strayed captured this beautifully in asserting that “when you’re speaking in the truest, most intimate voice about your life, you are speaking with the universal voice” — the singular task of the nonfiction writer of personal narrative, which Gornick elegantly distinguishes from the demands of all other writing:

To fashion a persona out of one’s own undisguised self is no easy thing. A novel or a poem provides invented characters or speaking voices that act as surrogates for the writer. Into those surrogates will be poured all that the writer cannot address directly — inappropriate longings, defensive embarrassments, anti-social desires — but must address to achieve felt reality. The persona in a nonfiction narrative is an unsurrogated one. Here the writer must identify openly with those very same defenses and embarrassments that the novelist or the poet is once removed from. It’s like lying down on the couch in public — and while a writer may be willing to do just that, it is a strategy that most often simply doesn’t work. Think of how many years on the couch it takes to speak about oneself, but without all the whining and complaining, the self-hatred and the self-justification that make the analysis a bore to all the world but the analyst. The unsurrogated narrator has the monumental task of transforming low-level self-interest into the kind of detached empathy required of a piece of writing that is to be of value to the disinterested reader.

Yet the creation of such a persona is vital in an essay or a memoir. It is the instrument of illumination. Without it there is neither subject nor story. To achieve it, the the writer of memoir or essay undergoes an apprenticeship as soul-searching as any undergone by novelist or poet: the twin struggle to know not only why one is speaking but who is speaking.

Illustration by Mimmo Paladino for a rare edition of James Joyce’s Ulysses.

This, Gornick argues, call for a clarity of intention that still makes room for complexity of feeling — that difficult art of holding opposing truths and walking forward with grace. The eulogist had to bridge this clarity of intent on the one hand (to celebrate and commemorate the dead), with recognition of her own mixed feelings on the other (the deceased mentor had been an often difficult but ultimately life-changing presence for the eulogist, “an agent of threat and promise”). Gornick considers how this particular task illuminates the general task of the writer of personal narrative:

First she sees that she has [these mixed feelings]. Then she acknowledges them to herself. Then she considers them as a way into the experience. Then she realizes they are the experience. She begins to write.

Penetrating the familiar is by no means a given. On the contrary, it is hard, hard work.

Returning to the essential interplay of situation and story, Gornick turns to the specific case of autobiography — perhaps the highest, most concentrated effort to take charge of one’s own narrative through a form of highly controlled privacy made public. (For a most enchanting exemplar, see Oliver Sacks’s masterwork of the genre.) She writes:

The subject of autobiography is always self-definition, but it cannot be self-definition in the void. The memoirist, like the poet and the novelist, must engage with the world, because engagement makes experience, experience makes wisdom, and finally it’s the wisdom — or rather the movement toward it — that counts… The poet, the novelist, the memoirist — all must convince the reader they have some wisdom, and are writing as honestly as possible to arrive at what they know. To the bargain, the writer of personal narrative must also persuade the reader that the narrator is reliable.

With an eye to the masters of the genre — Joan Didion, Edmund Gosse, Geoffrey Wolff — Gornick extracts the common denominator of uncommonly excellent personal narrative:

In each case the writer was possessed of an insight that organized the writing, and in each case a persona had been created to serve the insight.

[...] I become interested then in my own existence only as a means of penetrating the situation in hand. I have created a persona who can find the story riding the tide that I, in my unmediated state, am otherwise going to drown in.

TAKE AWAYS:

WHEN WRITING A MEMOIR:

What is the insight or wisdom you wish to convey through the telling of your story?

Which of "self" of yours is the best one to represent this story and deliver this insight?

SITUATION + STORY = GOOD WORK

The situation is what happened - the organizing principle that determines the structure and order of your remarks about it

The story is the emotional experience of you, the writer and storyteller

Clarity of intention is key: Who is speaking and why?

#memoir#narrative#personal narrative#personal writing#writing#amwriting#storytelling#memoirist#brain pickings#maria popova#writers#writing resources

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Einstein on Free Will and Imagination's Power

This week’s post highlights a very intriguing article by one Maria Popova who features an interview of Albert Einstein from the early 20th Century and gives us some background into his thinking and feelings of free will and its impact on our imagination. Since imagination and creativity go hand in hand, I felt it appropriate to include this blog post in my creativity series.

���Human being,…

View On WordPress

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

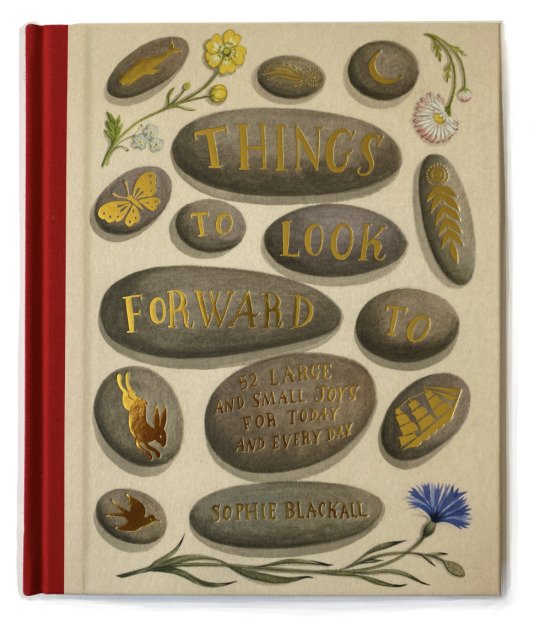

"What makes the book so wondrous is that each seemingly mundane thing on the list shimmers with an aspect of the miraculous, each fragment of the personal opens into the universal, each playful wink at life grows wide-eyed with poignancy.

Indeed, the entire book is one extended love letter to life itself, composed of the miniature, infinite loves that animate any given life (Maria Popova)".

13 notes

·

View notes

Quote

To go into solitude, a man* needs to retire as much from his chamber as from society. I am not solitary whilst I read and write, though nobody is with me. But if a man would be alone, let him look at the stars.

[…]

In the woods, we return to reason and faith. There I feel that nothing can befall me in life, — no disgrace, no calamity, (leaving me my eyes,) which nature cannot repair. Standing on the bare ground, — my head bathed by the blithe air, and uplifted into infinite space, — all mean egotism vanishes. I become a transparent eye-ball; I am nothing; I see all; the currents of the Universal Being circulate through me; I am part or particle of God.

Emerson, Nature

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Peek Inside My Head (a pull from my personal essay class)

A Peek Inside My Head

I am far from a simple girl. I take pride in what I know and interest in what I don't. Like Professor Graham, I don't particularly favor letting strangers take a peek into my mind. Yet, I want to be a writer. What's great is I get to be incharge of the work I display. If I think I've let my brain leak a little too much on the page, I can discard the piece. Though, for this particular assignment, I have allowed all the leakage to stream freely. In this essay I touch on what makes my brain wander far, ignorance, and a personal goal. Gifted with a grand amount of vulnerability, here is a look into my brain.

As a nineteen year old girl, numerous things make my brain go “hmmm.” For example, taxes or even something less complex like the mind of a nineteen year old boy. (slightly kidding!) Both of these things make me wonder. However, those ideas do not live in my brain. The concept of life and love, do. It has been argued for generations about how humans evolved on this giant rock and what our significance is. To me, the soundness of how we managed to get here or transform into who we are doesn't matter. What matters is that we're here, I’m here, right now. Out of all the planets, solar systems, galaxies, and universes my soul seeks refuge on earth. And to have the ability to experience a deep connection full of raw emotion, on a giant rock, makes my brain go “hmmm.”

“Come on Man!” is what I would say to the owner of a 2011 Honda Civic after they’ve cut me off on the freeway. Bad driving drives me absolutely mad. Something I've noticed about bad drivers is that they justify their actions by saying something along the lines of “i've got somewhere to be.” So does everyone else. Maybe a child is in the back of their mothers minivan throwing up on the way to the hospital, an employee late for work on their third strike, or an old man on his way to visit his wife’s grave, regardless, everyone has somewhere to be. The danger factor also contributes to the issue. Putting other’s lives at risk is something that happens every time one gets behind the wheel. Thinking that your destination is more important than everyone else’s is ignorant. Ignorant people cause me to scream “come on man!” on the freeway.

J’apprends le français mais je ne suis pas très bon. In English, this phrase translates to “I am learning French but I am not very good”. Before understanding life as I do now, I had no interest in learning another language. But, I got to college and all of the sudden my mind began to explore new ideas and opportunities. At first, I hated attempting to grasp how the French communicate. C’est difficile. Nonetheless, after indulging in a semester or two, I have fallen in love with trying. To be brutally honest, I suck at remembering and pronunciation is killer. I am far from great, some might even say horrible, but get back to me five years down the line. I might be conversing with a local under the brightly lit night sky in Paris, fluently. I am not good at speaking French but I strongly wish to be.

As stated before, I consider myself out of the box labeled “simple.” This consideration has its pros and cons. I see life and love through the eyes of youth and I have the capacity for a new language. With this, I also overthink about people who change lanes too quickly. I hope I have shed light on how I think and why I do so, in an admirable fashion.

#personal essay#corecore#university#universe#loveordietrying#reading#poetry#poems on tumblr#poem#college life#student life#college#paperback#writing#creative writing#brain pickings#life and love#aspiring writer#aspiring poet#perception#personal piece#for tumblr

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

"... to let the rustling of the leaves beckon forth the stirrings and murmurings on the edge of the psyche, which we so often brush away in order to go on being the smaller version of ourselves we have grown accustomed to being out of the unfaced fear that the grandeur of life, the grandeur of our own untrammeled nature, might require of us more than we are ready to give."

- Maria Popova

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

#hannah arendt#martin heidegger#maria popova#the marginalian#brain pickings#TIL about hannah arendt and martin heidegger

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

By awareness of life we are inspired to live.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Let there be spaces in your togetherness,

And let the winds of the heavens dance between you.

0 notes

Text

Andre Maurois: Acts, habits and destiny

André Maurois (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

“If you create an act, you create a habit. If you create a habit, you create a character. If you create a character, you create a destiny. ”

—Andre Maurois

View On WordPress

#Andre Maurois#Brain Pickings#First Things First#Proactivity#Religious habit#Stephen Covey#The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People

0 notes

Text

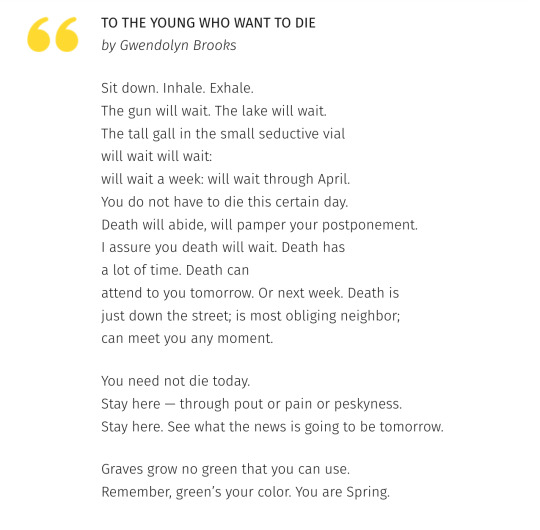

Gwendolyn Brooks' "To The Young Who Want To Die" from her 1987 collection "The Near-Johannesburg Boy and Other Poems."

#Gwendolyn Brooks#To The Young Who Want To Die#The Near-Johannesburg Boy and Other Poems#1987#1980s#Poetry#Quote#Quotation#Brain Pickings#The Marginalian

0 notes

Text

Truelove

"... and if you wanted

to drown you could,

but you don’t

because finally

after all this struggle

and all these years

you simply don’t want to

any more

you’ve simply had enough

of drowning

and you want to live and you

want to love and you will

walk across any territory

and any darkness

however fluid and however

dangerous to take the

one hand you know

belongs in yours."

David Whyte

Full poem here

0 notes