Text

Wonderful read for library lovers, bibliophiles and scholars: J. Pierpont Morgan's Library as An Architectural Archetype: An Aesthetic Encounter

The Home Library: A Unique Place

To create one’s own library is the natural impulse of devoted bibliophiles and lukewarm intellectuals alike. Whether it’s a single bookshelf above a desk, or a dedicated room in a grand mansion, the home library evokes a distinct mood.

Independent of their contents, the mere presence of books stimulates our appetite for learning. It inspires intellectual confidence and humility simultaneously; as a consequence of this tension, it sparks creativity.

How exactly does the aesthetic of the home library accomplish all this?

I’ve often wondered, (reposed against a backdrop of my own books.) But it wasn’t until immersing myself in the actualized, architectural archetype of “the home library,” J. Pierpont Morgan's Library, that I experienced the answer.

The Symbolic Mirror of Books Kept

A person’s home library is a mirror that reflects to them and others a multifaceted and dynamic individuality.

Unlike public libraries, which are curated and designed to meet the needs of a community, home libraries are always intimate extensions of the individuals who create them. Just as my library began long ago as a tender attachment to the books I was raised on, most home libraries are accumulative, lifelong endeavors, growing as we do, showing us not only our interests and values, but more broadly who we are, who we were, and who we might become.

As symbols, the books we keep and care for tether our sense of self to the ideas and knowledge they contain. To see them is to see our interests and values reflected back to us, and because this image is controllable, it is comforting. For example, ownership of Wittgenstein reflects someone who is, or at least wishes to be, philosophical and inquisitive. Romance novels, on the other hand, reveal an esteem for the amorous.

The books in our personal libraries also signify our connectedness with people. Firstly: past, present and future versions of ourselves. The books we’ve read hold memories of who we were when we read them, while the books we haven’t read yet contain who we might become if we do. (We keep these potentialities literally within arm’s reach.) Secondly, our kept books connect us to their authors: Memoirs on our bookshelves, for example, narrow the distance between our simple lives and the lives of heroes and history makers. Thirdly, the books we own are signals of relatedness with other readers. Consider, for example, visiting someone’s house for the first time and finding your favorite book on their mantlepiece.

Most interestingly, books are abstractions—thoughts, ideas, imaginary worlds—in concrete form. As such, books are physical bonds that prove the human being’s dual-occupancy of a physical reality and a metaphysical reality. To own books, to cherish them, is to acknowledge and to honor this dual-natured existence of ours.

A Sacred Creation of Self-Expression

...

[read the full essay here.]

#writing community#book lovers#books#library#library aesthetic#aesthetics#bibliophile#bookstagram#bibliomania#libraries#the morgan#the morgan museum#morgan library#interior design#altar#JP Morgan

1 note

·

View note

Text

A visual poem is one that must be seen to be fully understood, where the verbal and visual draw strength from each other to produce greater meaning. As such, visual poetry invites us to consider not just the typographic elements of verse—the shape of letters, the spaces between words, the overall composition of a page—but also the poetic potential of images.

In our workshop on visual poetry we followed a progression of ever more acutely visual forms, from technopaegnia (a tradition of “shaped poems,” of which George Hebert’s “Easter Wings” is an oft-cited example) to asemic writing, where the semantic function of language is removed entirely, as in works by mIEKAL aND or Rosaire Appel. Defining a collage-centric lineage of intermedia practices from Dada to Lettrism to Situationism and Fluxus, we lingered on specific works with roots in those traditions: the “typewriter poems” of Dom Sylvester Houédard, Sarah J. Sloat’s diagrammatic erasures augmented by collage, the swirling “tangle of language” in Ava Hofmann’s “[A woman wandered into a thicket],” the typographic abstraction of Andrew Topel’s “Black on White on Black,” and Tony Fitzpatrick’s multimedia collages, with their densely layered personal and social iconographies. We also discussed several visual artists who employ text, among them Ray Johnson and Deb Sokolow, whose work, while not necessarily poetic in intent, nevertheless contains some gnomic inscrutability that seems to tune our awareness to the frequency of poetry.

As with any practice that operates across arbitrary borders of medium and technique, the possibilities offered by visual poetry can make a blank page extra intimidating. The following prompts were inspired by questions from workshop participants, and each represents a potential starting point for exploring the intersection of words and images.

Prompt 1: Diagram a sequence

Choose a diagram you find visually interesting. Instruction manuals and science textbooks are an excellent source.

Remove or cover all the labels and captions.

Now consider something you wish would happen. What are the steps between here and there? What does the end result look like?

Describe each on a sheet of paper. Be as florid as you like.

Cut out each “step” and assign it a position on the diagram. Don’t think too hard about this part.

For inspiration, see Nance Van Winckel’s Book of No Ledgeor Flat-Pack by Anney Bolgiano.

Prompt 2: Visualizing voices

Start a collection of interesting words or phrases cut out of newspapers and magazines.

Choose one of these at random (draw from a hat, or close your eyes and pick one up). Paste it down in the center of a piece of paper.

Now choose the cutout that feels most like a response. Where does it belong in relation to the first? Does it agree? Disagree? How would that look visually—is it close or far away? Intersecting? Overlapping? Think about the different voices implied by differences in typography. Is the reply louder? Quieter? Paste it in place.

Repeat, with the phrase that seems to respond to what you just pasted down. Keep repeating.

For inspiration, see the work of Douglas Kearney.

Prompt 3: Finding images in letters

Start a collection of large text: newspaper and magazine headlines, chapter titles.

Cut out individual letters or words.

Now choose some of the most interesting letterforms and slice them further, vertically and/or horizontally.

Put several of these into your hands, a bag, or a hat, and shake them up. Drop them onto a blank sheet of paper.

Glue a few of these down where they landed. Now begin filling in the gaps, finding points of connection. Try to think of these as purely visual objects.

For inspiration, see the work of Geof Huth and Cecil Touchon.

Prompt 4: Score an event

Choose a situation that involves a series of repeating events or gestures. This could be a sporting event, the traffic passing by your window, the sounds you hear in a cafe.

Observe for a few moments in order to choose 6 to 16 “events” that are likely to recur. Design a mark or symbol to represent each event. For example, if you are watching traffic, create symbols for cars, trucks, motorcycles, bicycles. Consider how you can represent the direction a vehicle is traveling, its color or sound.

Decide on a time frame you’ll observe and divide a sheet of paper into units. For our traffic example, we could sample ten minutes by drawing ten lines on a sheet of paper.

Observe, using your system of symbols to record events as they occur.

For inspiration, see the drawings of Lee Walton or Rosaire Appel’s “Unsettled Scores.”

Prompt 5: Simple asemic writing

Coat the palm or side of your dominant hand with ink, paint, or graphite.

Now hold an imaginary pencil and write about a memory you don’t want to forget. Aim for five minutes, replenishing the ink or graphite at the end of each stanza or sentence.

#visual poetry#poetry#visual arts#visual language#poets#visual poems#writing prompts#prompts#writing exercises

0 notes

Text

"The child of both poetry and the visual arts, visual poetry has a double set of interests and its forms are myriad."

Click through for a Portfolio of Twelve (12) Works that exemplify this form...

0 notes

Text

Brand Building for Burgeoning Poets—Why it Matters and How to Do it Well

The post below is the November 8, 2023 issue of TellTellPoetry.com's newsletter. Sign-up for the newsletter on their website.

Brand Building for Burgeoning Poets—Why it Matters and How to Do it Well

You know your writing is good. Your friends and family adore the samples you’ve shared. Teachers in school wrote notes in the margins of your homework saying things like “Great voice!” and “Your word choice is spectacular.” But now that you’re working on getting people who aren’t in your inner circle (yet) to fall in love with your poetry, you feel overwhelmed. It might seem like standing out among thousands of other talented authors is going to be a near-impossible task, but it doesn’t have to be.

As an emerging author, it’s important to realize that you aren’t just trying to “get your words out there.” Of course, that’s your bread and butter, but your brand is a vital tool that will help you publish your poetry and connect with a wider audience. If you can dial in your unique voice, use consistent themes, personalize your aesthetic, and build authenticity into your persona, you’ll be growing a loyal fanbase before you know it.

Let’s dive in.

Find and Hone Your Unique Voice

The first step in laying a good foundation for your poetry brand is knowing who you are, and how you sound. Your voice is what sets you apart from other authors, and will ultimately be one of the most important aspects of retaining readership. It’s the way you share personality through the page via syntax, grammar, tone, imagery, rhythm, diction, punctuation, and more.

Take these poems, for instance:

Tell me it was for the hunger

& nothing less. For hunger is to give

the body what it knows

it cannot keep. That this amber light

whittled down by another war

is all that pins my hand

to your chest.

– Ocean Vuong

I drove all the way to Cape Disappointment but didn’t

have the energy to get out of the car. Rental. Blue Ford

Focus. I had to stop in a semipublic place to pee

on the ground. Just squatted there on the roadside.

I don’t know what’s up with my bladder. I pee and then

I have to pee and pee again. Instead of sightseeing

I climbed into the back seat of the car and took a nap.

I’m a little like Frank O’Hara without the handsome

nose and penis and the New York School and Larry

Rivers. Paid for a day pass at Cape Disappointment

thinking hard about that long drop from the lighthouse

to the sea. Thought about going into the Ocean

Medical Center for a check-up but how do I explain

this restless search for beauty or relief?

– Diane Seuss

They descend from the boat two by two. The gap in Angela Davis’s teeth speaks to the gap in James Baldwin’s teeth. The gap in James Baldwin’s teeth speaks to the gap in Malcolm X’s Teeth. The gap in Malcolm X’s teeth speaks to the gap in Malcolm X’s teeth. The gap in Condoleezza Rice’s teeth doesn’t speak. Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard kisses the Band Aid on Nelly’s cheek. Frederick Douglass’s side part kisses Nikki Giovanni’s Thug Life tattoo. The choir is led by Whoopi Goldberg’s eyebrows. The choir is led by Will Smith’s flat top. The choir loses its way. The choir never returns home. The choir sings funeral instead of wedding, sings funeral instead of allegedly, sings funeral instead of help, sings Black instead of grace, sings Black as knucklebone, mercy, junebug, sea air. It is time for war.

– Morgan Parker

Clearly, these authors’ writing styles vary greatly, which affects how we perceive their work. The je ne sais quoi of each writer’s voice ties together the other elements of their writing for truly unique, recognizable work.

Maybe you were lucky enough to find your voice early—if so, congrats! If, like many, you’re still working on it, fear not. There are plenty of ways to strengthen your voice through writing exercises, intentional reading, freewriting, and more. The more you work at it, the more confident you will become in your writing.

If consistent writing isn’t helping, try studying the works of authors with distinct voice and see if you can notice what makes their writing truly theirs.

Crafting Your Poetry Brand

Once your voice is dialed in, it’s time to focus on how you present yourself and your work. The themes you write about, your style, and your tone should become consistent, so that someone who reads your work can tell you wrote it, even if your name isn’t on the page.

Think of how you want the look of your work to feel. Do you want it to feel like a cozy reading nook? A surf shop? A yoga studio? A greenhouse? A midnight walk down 5th Avenue? Consider your voice, the tone of your writing, and your authentic personality, and match your look to them. Your aesthetics will become part of your calling card across cover art, social media, your website, in-person signage, and beyond, so it’s important to get them right.

Build a Memorable Author Persona

Both online and in person, getting people to want to revisit your work relies on a consistent persona. Social media and (eventually) your website will be key places you engage with your audience. Make sure to respond to comments, reach out to other authors, and cultivate a community around your work.

Authentic interaction is a huge draw and will not only help grow your audience, but it will make sure your audience is made up of “your people.” You don’t have to turn your life into a 100%-always-on content-fest, but make sure that the content you do share isn’t overly polished. Just be real with people and they’ll respect it. Relatability is rad.

Of course you’ll need to extend your persona beyond the internet, but being consistent with your brand at in-person events isn’t tricky if you’re being yourself (again…just be real and people will respect it). You’ll attract the type of people you want reading your poetry much more easily this way than if you try to be someone you’re not.

Need some inspiration? Check out these website for a few stellar examples of authors who have crafted an authentic online experience that reflects who they are. Note the continued elements between social pace and website, as well as what each does differently:

Chen Chen Website | Social

Sam Payne Social

Marya Layth Website | Social

So You Built a Brand. What Next?

You honed your voice, you put together a killer aesthetic, and you’re starting to see your audience grow. Using this personal brand as a foundation, shift your focus to getting your work in front of as many eyes as possible. Luckily, there are plenty of avenues to explore. Whether you’re marketing a book, a self-published poetry collection, or submitting your work to literature magazines and journals, it’s important to get your writing somewhere people can see it. That can (and should) be done on social media, but make sure to check out local poetry scenes as well as online communities. You’ll make valuable connections with your target audience and maybe even set yourself up for a mutually beneficial collaboration or other project down the road!

Consistency in your branding is key, but consistency in your writing is also key (no surprise there). Getting your brand up and running, and promoting your work afterwards, will be work. But make sure to keep writing with frequency—after all, that’s why you’re ultimately doing this in the first place!

And don’t forget—feedback is your friend. Listen to what others have to say about your style, your look, your tone, etc. Even if it is a criticism, the people you care about just want to see you succeed. Sure, you don’t have to pay attention to trolls on the internet, but if you value someone’s opinion, let them give it to you.

Get After It.

Alright, that was a lot. But a good lot. Hopefully your mind is bursting with thoughts on what your wonderful brand will one day look, sound, and feel like, but remember, you can take it one step at a time. Rome wasn’t built in a day.

Nail your foundation by establishing your distinct voice, settle in on a “vibe” for your brand, and implement your plan with consistency and authenticity. You’ll reap what you sow here, and we’ve got total faith you’re going to like what you come up with.

Crafted by Liam Norman.

Liam Norman is a midwest-based writer. With a propensity for movement, a passion for exploration, and an insatiable urge to create, storytelling is a natural extension of his interests. When he’s not writing, you can usually find Liam running the trails of Minneapolis, poking around the outdoors, hosting a get-together, or curating a fresh playlist. You can contact Liam at [email protected].

The post Brand Building for Burgeoning Poets—Why it Matters and How to Do it Well appeared first on Poetry editing services.

#telltellpoetry#poetry#editing#writers#writing#find your voice#your voice#voice#unique style#writing style#writing exercises#distinct voice#writerscommunity#writerslife#poets on tumblr#writers and poets#newsletter

1 note

·

View note

Text

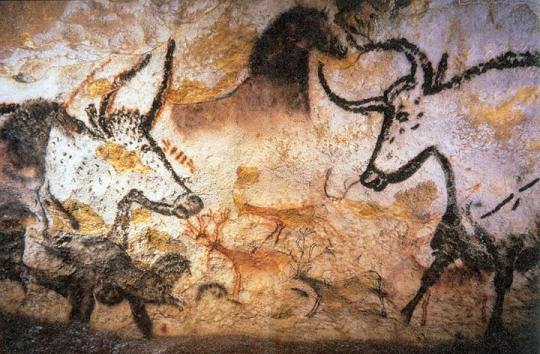

Depiction of aurochs, horses, and deer

The cave paintings of Lascaux reveal how stories are the custodians of our values and cumulative wisdom. They reflect our shared past and fate. They are part and parcel of the human community, and a central part of what it means to be human. We are storytelling animals, and always have been.

-- Alexandra Hudson, The Storytelling Animal

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

0 notes

Text

One must be drenched in words, literally soaked in them, to have the right ones form themselves into the proper pattern at the right moment.”

— Hart Crane, from a letter quoted in Hart Crane: The Life of an American Poet by Philip Horton (Norton, 1937)

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

“What is erotic about reading (or writing) is the play of imagination called forth in the space between you and your object of knowledge. Poets and novelists, like lovers, touch that space to life with their metaphors and subterfuge. The edges of the space are the edges of the things you love, whose inconcinnities make your mind move. And there is Eros, nervous realist in this sentimental domain, who acts out of a love of paradox, that is as he folds the beloved object out of sight into a mystery, into a blind point where it can float known and unknown, actual and possible, near and far, desired and drawing you on.”

— Anne Carson, from Eros the Bittersweet (Dalkey Archive Press, 1998)

#Anne Carson#erotic#imagination#creativity#eros#love#love of writing#writing love#writer love#writing#amwriting

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

https://www.wordstream.com/blog/ws/2022/01/20/copywriting-techniques

What is phonosemantics?

Phonosemantics (aka phonoaesthesia, aka sound symbolism) is a portmanteau word defining the theory that meanings come from sounds. Each sound, or phoneme, carries a specific psychological impression. Whereas onomatopoeias are a category of words that define themselves in the way they are pronounced, phonosemantics says that any word can make an impression based on the way it’s pronounced. It’s a form of copywriting psychology.

Which explains why you guessed Grataka as the land of mean-spirited hunters:

Hard /g/ and /k/, together with abrupt rhythm and short vowels, make this word sound rude. And the citizens of Lamoniana seem good fellows because of soft /l/, /m/, /n/, long vowels, and polysyllabic rhythm in their land’s name.

Phonosemantic associations

To illustrate phonosemantics, here are some phonemes and the associations they trigger:

/r/ – movement and activity

/p/ – precision and patience

/mp/, /str/ – force, efforts

/o/, /u/, /e/ – powerful, strong, authoritative

/b/ – round, big, and loud

/i/, /ee/ – small size, tenderness

/gl/ – shining, smooth, brightness

/l/, /n/ – soft, gentle

Phonosemantics is not new.

Sacred texts of Hindu philosophy (The Upanishads) describe mute consonants (b, c, d, f, g, p, t) as those representing the earth, fire, and eyes; sibilants (/s/) as representing the sky, air, and ear; and vowels representing heaven, the sun, and the mind.

Plato believed people could choose names for things depending on their features and the features of the sounds. In his book Cratylus, he suggested the letter and sound /r/ for the expression of motion and activity.

Russian scientist and poet Lomonosov suggested writers use the repetition of /i/, /e/, and /yu/ for creating the effect of something tender, pleasant, and soft, while repeated /o/, /u/, and /y/ would work to depict something terrifying, dark and cold.

Sound symbolism & the bouba-kiki effect

The mechanism of sound symbolism is yet unknown, but one suggestion is that it lies in verbal gesture—the way we use lips and tongue to pronounce the word. This concept, the bouba-kiki effect, was first introduced with an experiment in 1929 and has been confirmed by more recent studies.

In the experiment, participants were shown the below two shapes and asked which one is bouba and which one is kiki.

https://www.wordstream.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/copywriting-strategy-phonosemantics-bouba-kiki.jpeg

Ninety-five percent of people call the spiky one kiki and the rounded one bouba because those visual shapes align with what our lips do to say these words.

One of the most prominent researchers in sound symbolism, Margaret Magnus, nails it in her book Gods in the Word. She explains that:

Many words beginning with /b/ relate to so-called “barriers, bulges, and bursting” headings because our lips come together and form a barrier to the airflow when creating the /b/ sound. It results in a bulge and a burst of sound.

When pronouncing “kiki,” on the other hand, our lips narrow and our tongue makes a kind of sharp movement, therefore increasing Kiki’s chances to appear spiky.

Another idea around why this happens involves the connections between sensory and motor areas of the human brain. When hearing a sound, the brain doesn’t leap to a concept but associates it with a shape, a color, or an emotion—and responds accordingly.

Phonosemantics is an argument of little substance for most linguists denying such a relationship between sounds and meanings. And yet, conventional linguistic theories don’t have any alternative explanations for the bouba-kiki effect.

6 phonosemantic copywriting techniques to influence your readers

When it comes to copywriting (impressive copywriting examples here), it may seem super challenging to choose particular phonemes and combine them accordingly to influence readers’ perceptions and emotions.

But that’s not so.

Sound symbolism is not as hard as it sounds and may come in handy when coming up with business names, advertising slogans, or headlines for your content assets. Here are six ways to use them in your content to hook readers and generate sticky messages.

1. Use repetition & alliteration

Repetition and alliteration are two great techniques to practice here and make your written words memorable and more powerful.

It stands to reason that you won’t focus on just these sounds when crafting your ad copy, emails, or other marketing assets. Consider it an alternative copywriting technique to try in headings, intros, or conclusions whenever applicable.

Here’s how Aaron Orendorff applies it to his blog posts at iconiContent:

/b/ is everywhere—big, round, and loud

Repetition is used to pinpoint attention

Alliteration encourages readers to speed up

https://www.wordstream.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/copywriting-technique-phonosemantics-writing-example.png

2. Insert sensory words

Phonosemantics refers also to choosing sensory words for your content.

These are words, mainly verbs and adjectives, that help readers see, hear, taste, and feel your content. Best described by Henneke Duistermaat, they are more potent than ordinary words thanks to their more descriptive phonic nature. (Emotional words and phrases are super-potent too!)

She highlights five types of sensory words, according to different senses they evoke from people reading them:

Sight, indicating colors, shape, or appearance.

Hearing, describing or mimicking sounds.

Taste/smell, relating to tastes or odors, respectively.

Tactile, expressing concepts, feelings, and textures.

Motion, aka active words describing movements.

https://www.wordstream.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/copywriting-techniquie-phonosemantics-sensory-words.png

While sensory words can make your copywriting more compelling and memorable, it doesn’t mean you should stuff your business or marketing content with them. One to two sensory words in a headline or an email subject line are already enough to hook the audience and add personality to your writing.

3. Bust out the bucket brigades

According to research, bucket brigades (aka transition words and phrases) affect reader comprehension. These words improve coherence by conveying the structure and providing logical connections between arguments. Bucket brigades influence a text’s readability, which is especially critical for introducing new content topics. They show information flow, serving as hooks to encourage us to keep reading.

Here goes the example from your humble narrator’s oldy-moldy guest post for SEMrush. In it you’ll see the following bucket brigades:

It is true; but it is also true

More than that

To cut a long story short

Not very inspiring, huh?

Keep reading to find out

https://www.wordstream.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/copywriting-techniques-bucket-brigades-examples.png

Bucket brigades also make for great SEO copywriting because they get and keep readers hooked—which can increase CTR and dwell time.

4. Converse with your readers

Notice also that I used conversational language in the above example. A writer can evoke particular emotions from readers with different types of bucket brigades. They engage a reader’s brain and create an impression of dialogue (rather than a lecture), making texts sound more “alive.”

Here are some additional words and phrases to use for conversational bucket brigades:

Look:

Let me explain why

Here’s the deal

More than that

On top of that

In other words

Put another way

What does this mean?

So what

How so?

My point is

Plus, conversational writing is also in our list of landing page trends for this year.

5. Drop soundbites

Going on and on and tasking your reader with keeping track of everything? This is one copywriting mistake to avoid through the use of soundbites.

These are short yet powerful and poetic phrases that can better communicate the essence of a writer’s idea and make readers remember the core message.

Journalists and essayists know it as a thesis statement, screenwriters call it a logline, and speechwriters refer to it as a slogan (unforgettable advertising slogans here). The trick here is to choose lexical items and stylistic devices that would express your core message best, so the audience can’t help but remember it.

A classic example is John F. Kennedy’s “Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country.”

Writing techniques like repetition and contrast make this soundbite so attractive. Playing metaphors, rhythm, and phonemes are also great to practice for soundbite creation.

Let’s take Henneke Duistermaat’s blog post at Copyblogger as an example:

https://www.wordstream.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/copwriting-strategy-soundbites-example.png

Write less. Read more.

Talk listen more.

What do we have here?

The alliteration of /r/ expresses activity and motivates readers to act.

The repetition of less/more gives the soundbite rhythm.

The contrast of less – more / talk – listen / write – read) hooks attention and makes the conclusion memorable.

Here are some ways to use soundbites:

Put them in the last sentence of a paragraph or post for the audience to remember.

Include them at the top of a section as the “tl;dr”

Write them as one-sentence paragraphs (bolded or using the callout quote feature in your CMS if you have one)

Share tweetable quotes through a click-to-tweet tool

Visually appealing, they hook and share core messages of blog posts for readers to remember.

https://www.wordstream.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/copywriting-technqiues-soundbite-example-click-to-tweet.png

6. Use paragraph rhythm to make your content sing

For better engagement and desired perception, your content needs to sound smooth, with each line flowing. Besides the above-mentioned bucket brigades, paragraph length/rhythm is your instrument to use for that.

Consider the classic example from Gary Provost, the author of Make Every Word Count:

This sentence has five words. Here are five more words. Five-word sentences are fine. But several together become monotonous. Listen to what is happening. The writing is getting boring. The sound of it drones. It’s like a stuck record. The ear demands some variety.

Now listen. I vary the sentence length, and I create music. Music. The writing sings. It has a pleasant rhythm, a lilt, a harmony. I use short sentences. And I use sentences of medium length.

And sometimes, when I am certain the reader is rested, I will engage him with a sentence of considerable length, a sentence that burns with energy and builds with all the impetus of a crescendo, the roll of the drums, the crash of the cymbals—sounds that say listen to this, it is important.

It’s all about the rhythm of your writings. So:

Use short paragraphs with spaces between them, like in the article you’re reading right now. A mere look at your content piece should create an impression that it’s easy to read. (The human brain is super lazy, remember?)

Switch between short and long sentences (like Provost’s example shows) to make your content sound smooth.

Blend your content with one-sentence paragraphs now and then to highlight ideas (soundbites, remember?), provide a smooth reader experience, and create a dramatic effect when needed.

Phonosemantics: complex word, simple and effective copywriting technique

Copywriting may have formulas, but it is very much an art and there are no limits to the creativity you can apply to your marketing assets. It stands to reason that phonosemantics isn’t the silver bullet for content creators to drive engagement, win over readers’ love, or improve sales. And yet, it can become a powerful weapon in the arms of a writer who knows how (and when) to use it.

The basics of sound symbolism will help you analyze short- and long-form content, generate brand names and slogans, and influence the buyer decision process with psychology.

Just rememeber, while phonemes can trigger feelings and help you create emotionally rich content, it’s context and content value that matters most. So, treat phonosemantics as a faithful assistant, not a devil helping you manipulate a reader’s mind. Here is a quick recap of the copywriting techniques we covered in this post

Alliteration and repetition

Sensory words

Bucket brigades

Conversational language

Soundbites

Paragraph rhythm

#phonosemantics#semantics#psychology#psychology of sound#linguistics#science#sounds#writing sounds#writing

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE QUESTION

"Does writing down what I think and saying what I think activate different parts of the brain and neuropathways? I feel I have an easier time writing than I do speaking, so I wonder. Thank you for your time and knowledge!" - Minski

THE ANSWER

Hi Minski,

Last week I was at the Society for Neuroscience conference (think: 31,000 neuroscientists in the San Diego Convention Center), and I decided the best (read: funnest) way for me to tackle your question was to crowdsource.

So, late on night, at a bar filled with neuroscientists, I posed your question to 3 other Stanford Neuroscience PhD students. Here’s what we came up with, in our informal brainstorming session.

One graduate student remembered a series experiments involving split brain patients (whose corpus callosum, the part of the brain that connects the left and right hemispheres, is severed). So in these experiments, the researchers presented a picture to a patient in such a way that the image filled only ½ of the patients visual field. The idea here is that the visual image would only be captured by one eye, and therefore predominantly only be encoded by one side of the brain (this is a feature of how the human visual system is wired). So the image is presented to only one side of the brain, and then the patients are asked to pick a second object that was associated with the original picture, from a larger sample of objects. So people would pick the object associated with the original picture. And depending on which side of the brain was processing the original image, when the researchers asked the people why they picked the second object, they couldn’t tell the researchers why. But if the researchers then asked the people to write down their reason, the people were able to do that just fine.

Another example comes from the laboratory of Dr. Michael Gazzaniga. His patient, V.J. had her corpus callosum severed as a treatment for intractable epilepsy. After her surgery, V.J. was no longer able to write, but was able to speak and understand spoken language without any problem. So the idea here is that speech and writing are lateralized functions in the brain. Indeed, experiment conducted with the help of V.J. and other split brain patients have lead to the understanding that spoken languages are stored/encoded on the left side of the brain, whereas writing is controlled by the right side of the brain. For a more in-depth discussion of V.J. and the lateralization of speaking/writing, I highly recommend a 1996 article published in the New York Times, “Workings of Split Brain Challenge Notions of How Language Evolved”, written by Sandra Blakeslee.

With our discussion now focused on lateralization of behaviors, another graduate student mentioned a book by Stanislas Dehaene, called Reading in the Brain. This book talks about a lot of ideas, but the basic premise is that there are a lot of visual pathways that words/concepts can go through, that are completely independent from the pathways that those same word/concepts go through when you are hearing them. But at some point, there is a convergence of those various pathways - at some level, there is part of your brain that deals with semantics, where the representation of the written word ‘manatee’, meets the representation of the spoken sound ‘manatee’, and presumably the representation of the image below. So there is a region of your brain that is going to be encoding language, but there seem to be different neural pathways for accessing that general region (visual, verbal, aural). Our discussion reiterated the observation that some people display selective aphasia; for these folks, if you put a picture of a cat in front of them, and ask ‘What is that?’, you’ll get a response of ‘It’s, an animal. Not dog.’ But they won’t be able to say ‘cat’. And if you ask these people to write down that the picture is, they’ll be perfectly able to write the word ‘cat’.

So with these extraordinary examples, our conclusion was that it is not at all unreasonable to think that a person could be better at written language than verbal language, and at expressing their comprehension of language better through writing as opposed to speaking. And indeed this point has been highlighted in non-neuroscience based studies of the most effective ways to teach children: whether teachers should talk to the students or should draw on the board.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Written and spoken language can exist separately in the brain, a new study from Johns Hopkins shows. The study looked at stroke victims with aphasia that impaired their communication capabilities in one way but not the other.

Researchers at Johns Hopkins, Rice and Columbia universities studied five stroke patients with aphasia, difficulty communicating after their strokes. Four could speak but not write sentences that took a certain form -- the study focused on affixes, such as the “-ing” in “jumping” -- while the last could write those sentences but not speak them.

“Actually seeing people say one thing and -- at the same time -- write another is startling and surprising,” Johns Hopkins cognitive science professor Brenda Rapp told the website Futurity. “We don’t expect that we would produce different words in speech and writing. It’s as though there were two quasi-independent language systems in the brain.”

Futurity, a nonprofit website that shares university research, explains, “While writing evolved from speaking, the two brain systems are now so independent that someone who can’t speak a grammatically correct sentence aloud may be able write it flawlessly.”

The study, titled “Modality and Morphology: What We Write May Not Be What We Say,” was published in the journal Psychological Science. The abstract summarizes, “The findings reveal that written- and spoken-language systems are considerably independent from the standpoint of morpho-orthographic operations. Understanding this independence of the orthographic system in adults has implications for the education and rehabilitation of people with written-language deficits.”

0 notes

Text

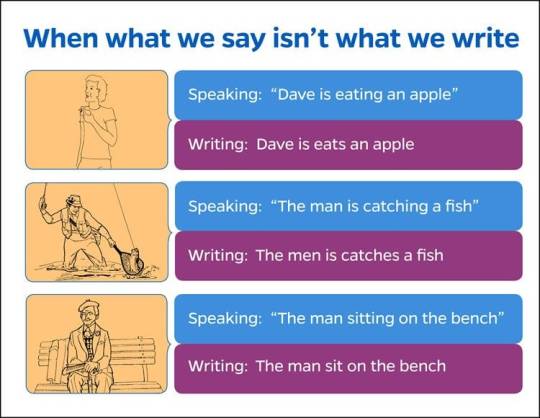

Out loud, someone says, “The man is catching a fish.” The same person then takes pen to paper and writes, “The men is catches a fish.”

Although the human ability to write evolved from our ability to speak, in the brain, writing and talking are now such independent systems that someone who can’t write a grammatically correct sentence may be able say it aloud flawlessly, discovered a team led by Johns Hopkins University cognitive scientist Brenda Rapp.

In a paper published this week in the journal Psychological Science, Rapp’s team found it’s possible to damage the speaking part of the brain but leave the writing part unaffected — and vice versa — even when dealing with morphemes, the tiniest meaningful components of the language system including suffixes like “er,” “ing” and “ed.”

“Actually seeing people say one thing and — at the same time — write another is startling and surprising. We don’t expect that we would produce different words in speech and writing,” said Rapp, a professor in the Department of Cognitive Science in the Krieger School of Arts and Sciences. “It’s as though there were two quasi independent language systems in the brain.”

The team wanted to understand how the brain organizes knowledge of written language — reading and spelling — since that there is a genetic blueprint for spoken language but not written. More specifically, they wanted to know if written language was dependent on spoken language in literate adults. If it was, then one would expect to see similar errors in speech and writing. If it wasn’t, one might see that people don’t necessarily write what they say.

The team, that included Simon Fischer-Baum of Rice University and Michele Miozzo of Columbia University, both cognitive scientists, studied five stroke victims with aphasia, or difficulty communicating. Four of them had difficulties writing sentences with the proper suffixes, but had few problems speaking the same sentences. The last individual had the opposite problem — trouble with speaking but unaffected writing.

The researchers showed the individuals pictures and asked them to describe the action. One person would say, “the boy is walking,” but write, “the boy is walked.” Or another would say, “Dave is eating an apple” and then write, “Dave is eats an apple.”

The team wanted to understand how the brain organizes knowledge of written language — reading and spelling — since that there is a genetic blueprint for spoken language but not written. More specifically, they wanted to know if written language was dependent on spoken language in literate adults. If it was, then one would expect to see similar errors in speech and writing. If it wasn’t, one might see that people don’t necessarily write what they say. Image adapted from the Johns Hopkins University press release.

The findings reveal that writing and speaking are supported by different parts of the brain — and not just in terms of motor control in the hand and mouth, but in the high-level aspects of word construction.

“We found that the brain is not just a ‘dumb’ machine that knows about letters and their order, but that it is ‘smart’ and sophisticated and knows about word parts and how they fit together,” Rapp said. “When you damage the brain, you might damage certain morphemes but not others in writing but not speaking, or vice versa.”

This understanding of how the adult brain differentiates word parts could help educators as they teach children to read and write, Rapp said. It could lead to better therapies for those suffering aphasia.

#linguistics#language#language acquisition#language learning#ESL#linguaphile#science#neuroscience#word choice#word selection#verbal fluency#article

1 note

·

View note

Text

Speaking is one of the actions we do the most every day and most people are very good at it: healthy fluent speakers can easily say 2–3 words per second, selected from tens of thousands of words in our mental dictionary (over 50,000 for adults!). The process of speaking, however, is not as simple in our brains as it seems when we are talking. Take, for example, naming a picture of an apple. Although the word apple comes easily to mind, several processes and brain regions are needed to allow us to fetch the word 'apple' from among all the words we have in memory. Choosing our words is just one of the steps we will describe below with the example of what our brain needs to do in order for us to name a picture of an apple.

Steps involved in choosing our words:

The first step is to think of the concepts associated with the picture of an apple. For example, a few concepts that are related to apples include sweet, crunchy, juicy, etc. These concepts help define what the object we see is; we can define an apple as a fruit that is sweet, crunchy, and juicy.

In the second step, we access all the words1 we associate with the concepts we thought of in step 1. The concepts associated with the picture of an apple can also be associated with words other than apple. Other words beside apple that might activate when we think about the concepts sweet, crunchy, juicy, etc. include pear, plum, or peach (see Figure 1).

The third step is word choice, during which the correct word needs to be selected from among all the activated words. This is what we are interested in researching. The brain needs to process very quickly to choose the right word during speech. Some researchers believe the language system needs help from other areas of the brain to process and choose words so that we can speak fast enough. These proposed areas outside of the language system that help with word choice are believed to support an “external selection mechanismAn external selection mechanism is a mechanism that is not directly a part of the language system but that can help the language system choose the right word when needed.” (in red in Figure 1).

Finally, after we pick a word, we have to say it out loud. To do that, we need the fourth step. During that step, the sounds we have stored in our brain, called phonemesA phoneme is a sound we have stored in the brain. We string each phoneme (sound) together to make a whole word—a lot like spelling using the alphabet! You can think of it like this: the alphabet is for written language and phonemes are for spoken/heard language., need to be activated. We string each phoneme together to make a whole word. It is almost like spelling using the alphabet. You can think of it like this: the alphabet is for written language and phonemes are for spoken/heard language.

apple—spelled with letters

æpәl—spelled using phonemes

And this whole process happens so fast that you never even realize you do all these steps every time you name an object!

Figure 1 - This is what happens in the brain when we name a picture.

First, we look at the picture and think about all the related concepts that help describe the picture. Second, we think about all the other words (lemmas) that can be described by those same concepts. Third, we select a word (lemma), with the help of an external selection mechanism (part of the brain outside of the language system that makes it easier to select words quickly), and use the brain’s knowledge of phonemes to say the word out loud.

Read more in link.

#linguistics#word choice#language#language acquisition#neuroscience#language science#linguaphile#article#science#apple

0 notes

Text

From my experience speaking in front of hundreds of audiences, I have learned that stories are memorable because of the images and emotions contained in them. The lesson of the story sticks because it’s embedded in an image. The image isn’t a still picture; it’s a motion picture, a movie.

Let’s test my theory. Take a moment now to think about a movie that you first saw more than ten years ago. Have you identified your movie? Now, what do you remember when you recall this movie?

I bet that the first thing that came to your mind was an image or a scene. You remember the actors, their clothes, the location, the situation, and the emotions. You can see these images as easily now as you did when you were watching the movie.

What you remember next is dialogue. But compared to how vividly you remember the images, you probably don’t remember much of the dialogue. Your brain remembers pictures first. It then remembers the emotional context, and finally, it remembers language.

In his book Brain Rules, molecular biologist John Medina explains this phenomenon. “When the brain detects an emotionally charged event, the amygdala releases dopamine into the system. Because dopamine greatly aids memory and information processing, you could say it creates a Post-it note that reads, ‘Remember this.’”

That explains why audience members who saw me tell a story in a keynote more than ten years ago approach me like I’m a long-lost friend and say, “I still remember your airport story.” But it’s what they say next that proves the effectiveness of my story theater method as an essential storytelling skill. With a smile on their faces, they say, “I’m still looking for the limo.”

“Look for the Limo” is the branded point of the story. I call it a phrase that pays. Because they remember the story, they remember the point. When they remember the point, it becomes actionable.

Most people who have ever given a speech, run a business meeting, or tried to sell a product or service will tell you that stories are more memorable than facts and data. In my experience, the story is essential if you want people to remember any of your content.

In his book Mirroring People, Marco Iacoboni asks, “Why do we give ourselves over to emotion during the carefully crafted, heartrending scenes in certain movies? Because mirror neurons in our brains re-create for us the distress we see on the screen.”

At last I’ve found a scientific explanation to explain what I’ve been teaching for the last 20 years: mirror neurons. We don’t just listen to stories; we see images and feel emotions. We experience the story as if it’s happening to us.

Daniel Pink says, “Stories are easier to remember because stories are how we remember. When facts become so widely available and instantly accessible, each one becomes less valuable. What begins to matter more is the ability to place these facts in context and to deliver them with emotional impact.”

In other words, when you tell a story and make a point, you make an emotional connection. When you make an emotional connection, you and your story are memorable.

0 notes

Text

"Identification" is the term we use to describe what happens to us when we meet fictional character we care about and grow to love. In Distinction, a study that defines popular culture in its relation to highbrow art, the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu argues that a so-called popular aesthetic (art designed for the masses) reveals "a deep-rooted demand for participation… the desire to enter into the game, identifying with the characters' joys and sufferings, worrying about their fate, espousing their hopes and ideals, living their life." In stark contrast to that euphoric state of breathless participation stands what Bourdieu calls a "bourgeois aesthetic," a style found in art works that espouse "disinvestment, detachment, indifference." The popular aesthetic found in the melodramatic plots of children's literature draws readers in, giving them the feeling that they have actually entered another world and are navigating it with the protagonist, but not, I would argue, as the protagonist. They are like participants, to be sure, but more like witnesses who watch events unfold and read the minds of the characters experiencing them.

From Bookworms to Enchanted Hunters: Why Children Read

Maria Tatar, The Journal of Aesthetic Education, Vol. 43, No. 2, Special Issue on Children's Literature (Summer, 2009), pp. 19-36 (18 pages) https://www.jstor.org/stable/40263782

#reading#readers#aesthetics#protagonist#amwriting#writers#writing resources#libraries#bookworms#jstor#reader#identification

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business. 20th Anniversary. Neil Postman with a new introduction by Andrew Postman. New York: Penguin Books, 1985.

In spite being published thirty-four years ago, Neil Postman’s Amusing Ourselves to Death is more relevant today than it was published in 1985, although the nature of the medium has changed from television to the iPhone and Internet and Las Vegas has been eclipsed by Silicon Valley as the metaphorical city of our national character and aspirations. We now live moreso in the world of the image and electronics rather than the world of the word and ear. The medium of this new way we interact with the world and with ourselves is the metaphor of how we see and exist as digital selves subject to constant manipulation by us, corporations, and governments. There is no constant, enduring self: only metaphors that continually change as new images appear.

The result of this “great media-metaphor shift” is that “much of our public discourse has become dangerous nonsense” (16). Postman shows how public discourse was generally more coherent, serious, and rational when print was the dominant medium of public discourse and how this has changed under the medium of television – and later the image and Internet – where emotive appeals are made by pundits, predictors, and public relationists. Although the older mediums of speech and word have not entirely disappeared, they have become supplanted by the image and do not dictate how we as citizens discuss things publicly. This fact strangely is overlooked by those who continue to advocate for some form of public reason or deliberative democracy, not recognizing that this activity presupposes the preeminence of the speech and word in the culture. It is not clear how public reason, whether in speech or in print, would break through the dominance of the image in our society.

The monopoly of the printed word in early American public discourse yielded the “typographic mind” that demanded logic, rationality, and evidence to structure argument. Even advertising was “regarded as a serious and rational enterprise” until 1890 “whose purpose was to convey information and make claims in propositional form” (59-60). The printed word shaped every facet of public discourse, creating an “age of Exposition”:

“Exposition is a mode of thought, a method of learning, and a means of expression. Almost all the characteristics we associate with mature discourse were amplified by typography, which has the strongest possible bias towards exposition: a sophisticated ability to think conceptually, deductively and sequentially; a high valuation of reason and order; an abhorrence of contradiction; a large capacity for detachment and objectivity; and a tolerance for delayed response” (63).

This age was replaced in the twentieth century by the “Age of Show Business” where communication became severed from transportation, beginning with telegraphy that erased state lines and connected the entire country together. The telegraphy created its own definition of discourse that “would not only permit but insist upon a conversation between Maine and Texas” (65) and, in turn, introduced “large scale irrelevance, impotence, and incoherence.” Information was a commodity that was context-free and did not have to serve any social and political function but only satisfy curiosity and interest. Newspapers soon followed suit with the speed of the news delivered and from what distances defining their mission rather than the quality or utility of the information provided. With this new abstract and remote information, people were confronted for the first time with too much information while simultaneously have their capacity for social and political action diminished, for “in both oral and typographic cultures, information derives its importance from the possibilities of action” (68).

The “Age of Show Business” was also when the image – initially in photography – eclipsed word and speech for how we communicate. Unlike language which represents the world as an idea, the image presented the world as an object to be controlled and manipulated. Lacking syntax or the capacity to be understood as a sequence of propositions, the image still today appeals to our emotions rather than our reason, with the resulting public discourse reduced to ad hominin attacks, virtue signaling, and political correctness.

When the image and instant communication came together as a single enterprise, first in television and later in the Internet, it became the only reality in which we acknowledge and with which we interact. Except for a few specialists, nobody knows how it works and thereby achieves the status of myth, becoming the reference point of our reality. Entertainment – amusing ourselves to death – is the content delivered not only because people want it but because the medium of the image dictates it. Unlike the printed word or speech, the image is impervious to rationality. And by the time one has rationally analyzed it, a new image has quickly replaced the old one.

Postman showed how the image has dominated the public discourse in our news, culture, religion, education, and politics in the 1980s so it is no longer rational, coherent, or relevant. Today one could say the situation has only gotten worse – as Andrew Postman intimates in the new introduction to this book – with every person, having access to an iPhone, being a director, actor, and screenwriter of his or her own show. Postman’s warning of our culture of becoming Huxleyan and burlesque, where we watch ourselves by our own choice, has proved to be true. Privacy is willingly given up for a technology that provides us the latest trends and toys for our amusement.

Postman concludes that “our philosophers have given us no guidance in this matter,” neglecting the role that technology plays in forming public ideologies (157). Philosophers have ignored the following questions Postman poses:

“What is information? Or more precisely, what are information? What are its various forms? What conceptions of intelligence, wisdom, and learning does each form insist upon? What conceptions does each form neglect or mock? What are the main psychic effects of each form? What is the relation between information and reason? What is the kind of information that best facilitates thinking? Is there a moral bias to each information form? What does it mean to say there is too much information? How would one know? What redefinitions of important cultural meanings do new sources, speeds, contexts, and forms of information require? Does television, for example, give a new meaning to “piety,” to “patriotism, to “privacy”? Does television give a new meaning to “judgment” or to “understanding”? How do different forms of information persuade? Is a newspaper’s “public” different from television’s “public”? How do different information forms dictate the type of content that is expressed?” (160)

Although philosophers have addressed questions about technology (e.g., the ethics of technology), not enough have written about the role of information, technology, and democracy. These questions are critical ones that need to be asked and answered for our democracy to survive and, in this sense, Neil Postman’s Amusing Ourselves to Death remains even more relevant than ever in this age of the image and the Internet.

#internet#the internet#modernity#technology#tech world#silicon valley#information#philosophy#21st century#20th century#important#favorite#image#speech#word#words#linguaphile#communications#communication#psychology

1 note

·

View note

Text

I think that Belle is this ultimate symbol of the fact that books can be rebellious, incredibly empowering, and liberating. You can travel to places in the world that you would never be able to, under other circumstances.

Emma Watson in an interview with Collider.

#belle#beauty and the beast#emma watson#library love#libraries#library lover#disney princess#library#books#book lover#bibliophile

34 notes

·

View notes