#cultural marxism

Text

youtube

309 notes

·

View notes

Text

"cultural marxism" is an antisemitic dogwhistle

hey fun fact for anyone who doesnt know, if you hear someone talking about "cultural marxists taking over", they mean jewish ppl. marx talked about economics and societal structure, not culture - which are two very different things when you recognise that he only spoke of societal structure in terms of economics.

"According to the theory of 'Cultural Marxism,' a group of Jewish Marxists called the Frankfurt School have profoundly reshaped society and public opinion; deciding to abandon the original Marxist goal of an international working-class revolution, they sought to implement socialism through a slow, creeping takeover of 'culture.' Under such names as 'political correctness' and 'multiculturalism,' so the theory goes, 'Cultural Marxists' indoctrinated and shamed 'the West' into abandoning Christianity, family, and nation in favor of a new worldview and system of control, involving mass immigration, sexual liberation, and moral and aesthetic decline."

(shout out to @darkfalcon-z for the source and correcting my original post! please reblog this version instead as the other had inaccurate information)

jewish people pls feel free to add anything you feel relevant

#bug talks#cultural marxism#judaism#jewish culture#karl marx#dogwhistle#leftist#right wing#communism#conservative#liberal#antifa#antisemitism#human rights#fuck kanye west#jewish ppl are probably the most persecuted group in history#i can Not believe people really think theres some secret society of jews that rule everything#like how fucking stupid can you be#it just goes to show jewish people have been the scapegoats for power hungry fascists for centuries

327 notes

·

View notes

Text

“ The most extreme possible agenda is now being assiduously (some might say ruthlessly) pursued by those around President Sock Puppet, and Americans are bearing the brunt of radical economic, racial, and cultural warfare that is tearing us apart rather than bringing us together.” <— Don’t say I didn’t warn you.

(From my blog archive)

#leadership#extremism#government#save america#biden#democrats#Biden is destroying America#cultural marxism

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

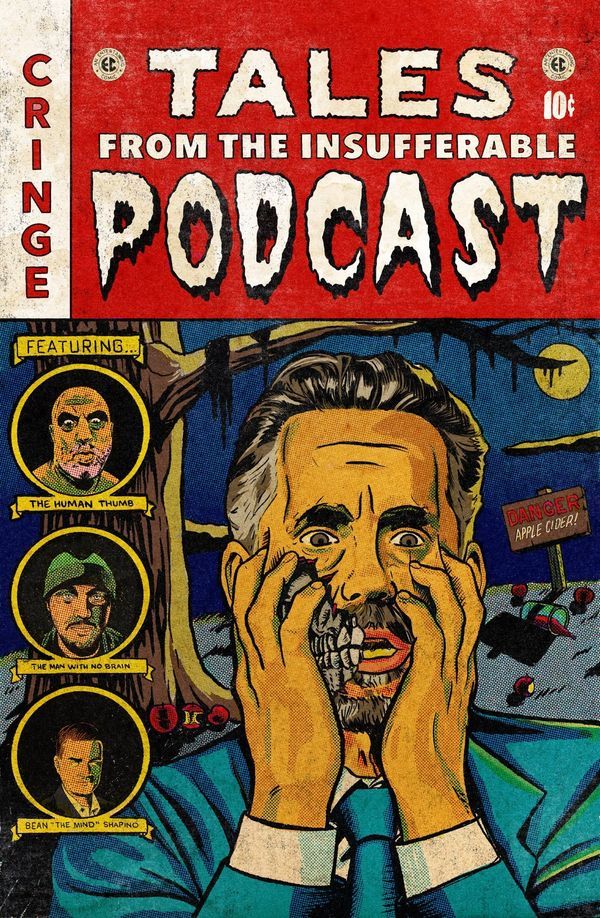

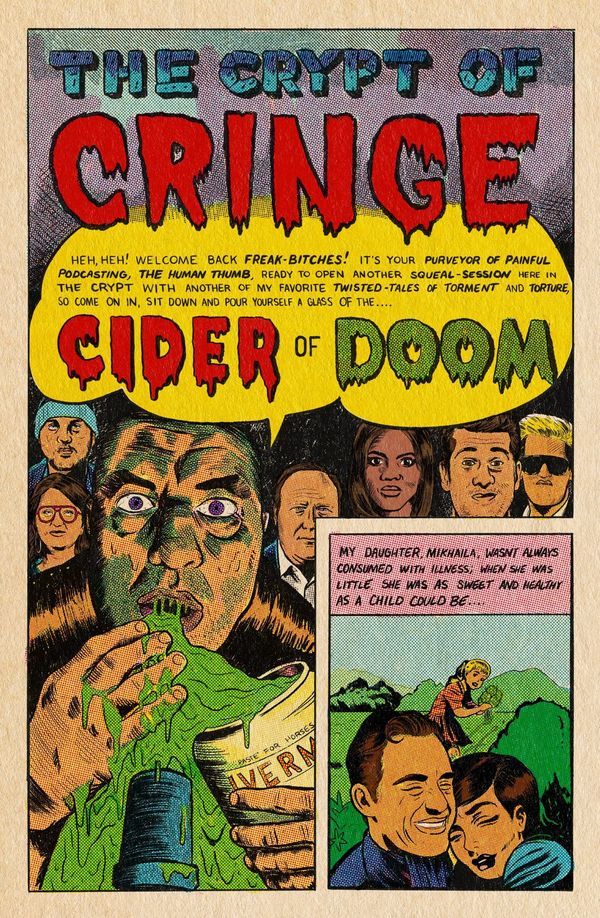

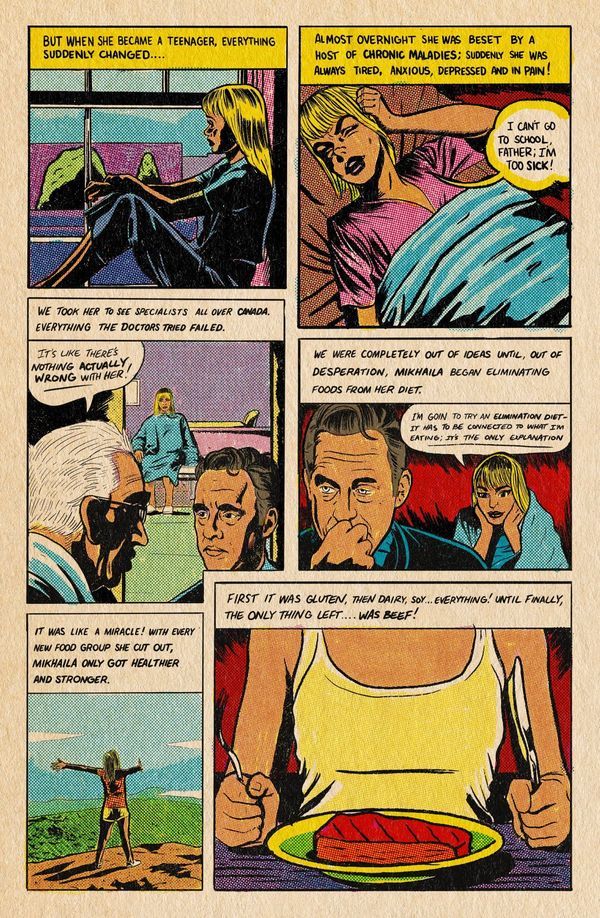

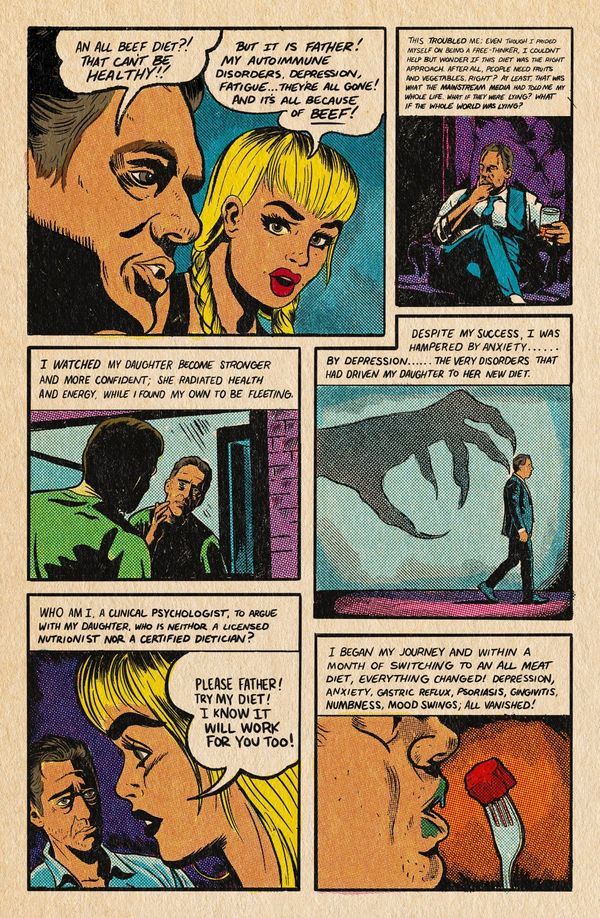

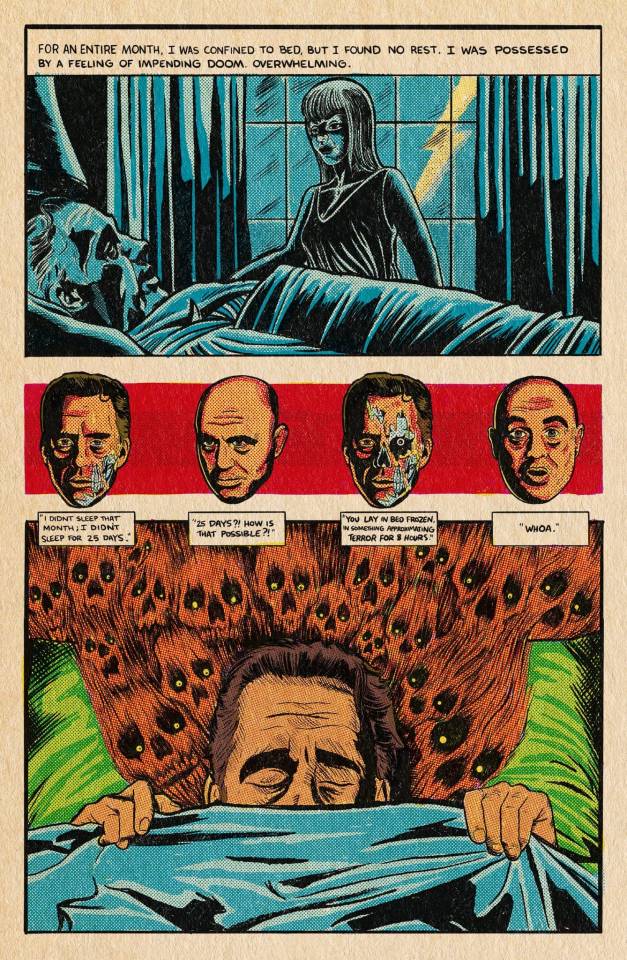

by the amazing @samalcarez (https://www.instagram.com/samalcarez/)

#antifa#jordan peterson#antifascist#joe rogan#the human thumb#antifascism#tim pool#the man with no brain#ben shapiro#bean the mind#cultural marxism#women are mystical dragons#sam alcarez

149 notes

·

View notes

Text

GamerGate 2: The Fempire Strikes Back

youtube

#gamergate#sweet baby inc#gamergate 2.0#razorfist#marxism#cultural marxism#gaming journalism#video games#pop culture#anita sarkeesian#the daily wire#matt walsh#culture war#politics#FBI#DHS#discord#Youtube

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Urban Dictionary Definition of “Cultural Marxism”

Cultural Marxism is sometimes labeled as a conspiracy theory by people on the far left, but this definition explains how most people use the term in political conversation:

Marxism can be summed up as the interpretation that the world is best understood as a power struggle between different wealth groups (poor, middleclass, rich, bourgeoisie, proletariot, etc). Cultural Marxism is a term used to describe the idea that our society is best interpreted as being a power struggle between different identity groups or cultures(women, men, gay, straight, black, white).

Cultural Marxism is used by most people refers to a kind of behavior that looks for power imbalances in everyday culture (like asking a person where they are from, or complementing a black persons hair) and problematizing those interactions, causing people to resent others for innocuous little social misdemeanors.

Cultural Marxism assumes the worst of the actions of a supposedly powerful group by saying that their little faux-pas are really egregious examples of latent prejudice, and excuses the hatred and rudeness of the supposedly weaker group by saying that their behavior is an expression of resisting power or "asserting their personhood".

Cultural Marxists hunt relentlessly to find things to be offended about, and claim to speak on behalf of all oppressed groups, though most of the time cultural marxists are rich, priviledged, upper and middle class white college women with multicolored hair.

"Like every moral busybody across history, Cultural Marxists always come at you with this famous glint in their eye that suggests that they know better than you how you should live your life and they will make you if they get the chance."

"Cultural Marxism is the practice of interpreting what people say in the most uncharitable way."

🌸Source🌸

#that awkward moment when the urban dictionary definition is more accurate the Wikipedia page#cultural Marxism#marxism

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Eddie Waldrep, PhD, MSCP

Published: May 15, 2023

This is a guest post by Edward E. Waldrep, Ph.D, M.S.C.P. Dr. Waldrep is a Veteran of the War in Iraq, Purple Heart recipient, and is currently a clinical psychologist for the Department of Veteran Affairs specializing in PTSD. Views expressed here are those of the author and are not the views of the Department of Veteran Affairs.

Our country, and indeed the world, has gone through a lot in the past couple of years. The COVID-19 pandemic, the murder of George Floyd by a police officer, a racial reckoning, rioting, and a tumultuous transition of presidential power that has marred our democratic institutions to name a few. With so much going on, the radical political changes within the American Psychological Association (APA) may have easily escaped the attention of many.

For example, the APA has been gradually changing the way race is approached. Officially, in 2017 it updated standards on multiculturalism to include embracing “intersectionality,” a conceptualization of the myriad ways in which one is oppressed via group identity. In 2019, a Task Force on Race and Ethnicity Guidelines in Psychology noted drawing upon Critical Race Theory (CRT) as a guide and in 2020 the definition of racism promoted by the APA was officially changed. The redefinition changed it from internal prejudicial beliefs and interpersonal discrimination to a “system of structuring opportunity.” What led to this change and why does it matter so much?

Social Justice versus Critical Social Justice

These changes came as a result of the changing focus of APA, and academia in general, from traditional social justice movements to Critical Social Justice (CSJ). Traditional social justice sought to end institutional oppression, discrimination based on immutable characteristics, focus on universal humanity of every individual, and for equality of opportunity for each to pursue their own self-directed goals. These are indicative of aspirational goals found in Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I have a dream” speech. There are contemporary organizations promoting the same pro-human ideals such as the Foundation Against Intolerance and Racism (FAIR) and many others. On the other hand, there is CSJ that has skyrocketed in the public sphere in recent years and is much more pernicious.

The boom of CSJ is not a mere phenomenon. It is the result of decades of planning referred to as “the long march through the institutions,” a neo-Marxist approach to establish the conditions for revolution. This built upon the work of Italian Marxist, Antonio Gramsci who developed the concept of “cultural hegemony.” Cultural hegemony was posited as an explanation for why the grand Marxist revolution and utopia had failed to manifest itself. Basically, if people were able to have a comfortable life in a free market society, then they lack the motivation to burn down western society to make way for the grand utopia.

Critical Critical Theory Theory

The hegemony is thought of as an invisible, largely undetectable, ubiquitous force that nobody intentionally directs but by which all are influenced. This is where the “fish in water” analogy stems from the that is commonly used to explain “white privilege.” In their book, Black Eye for America, Swain and Schorr (2021) note that the strategy to bring about communism is to dismantle or undermine western society by attacking five societal components that maintain the hegemonic “oppression”: educational establishments, media, the legal system, religion, and the family. Douglas Murray also noted this attack in his recent book, The War on the West.

CRT is just one iteration of the application of Critical Theory(1) to different aspects of society (e.g., race, gender, sexuality, queer, colonialism, etc.) and often is presented as diversity, equity, and inclusion. CRT and intersectionality have been encouraged to be adopted in cultural competencytraining and stem from the same origin. Intersectionality, applied socially, is designed to get people to think of how they are constantly oppressed, in any variety of ways, in any given situation, to promote social divisiveness. The concept of intersectionality was popularized by Marxist lawyer and key developer of CRT, Kimberle Crenshaw. In her 1991 article for the Stanford Law Review, she argues that universal humanity ought to be rejected and focusing on race should be retained and be used for political power.

This is the exact opposite of Dr. King’s approach. She makes the distinction between “I am black” vs. “I am a person who happens to be black”. She is critical of the latter and states, “’I am a person who happens to be black,’ on the other hand achieves self-identification by straining for a certain universality (in effect, “I am first a person”) and for concomitant dismissal of the imposed category (“Black”) as contingent, circumstantial, nondeterminant” (pg. 1297). Hence, the CRT focus on “centering race” to achieve ideological and political goals associated with imposing Marxist ideology to “dismantle” western norms and practices centering individual human rights and liberties.

The Modern Echoes of the Ugly History of Collectivist Ideologies

This ideology has a horrendous track record for humanity. Simply relabeling the ideology does not change that fact. American Psychologist, the “flagship publication” of the APA, went so far as to dedicate an entire special issue promoting this ideology in 2021. The edition editors criticize the field of psychology for “failing” to focus on structural power dynamics and for not creating “lasting social change” (Eaton, Grzanka, Schlehofer, & Silka, 2021). These are references to postmodern philosophy, Marxist structural determinism and social engineering. The authors go on to state “articles in this special issue build the case for a public psychology that is more disruptive and challenging than simply aiming dominant, canonical, and mainstream psychological research and practice outward” (pg. 1211).

Flynn and colleagues, 2021, discuss civil disobedience and criticize nonviolence as the only acceptable form stating, “we encourage psychologists to think critically about the effects of privileging certain acts of civil disobedience over others on the basis of decontextualized tactics alone, such as the assertion that property destruction invariably denotes a protest tactic outside the bounds of civil disobedience” (pg. 1220). They go on to describe strategies to twist and manipulate APA Ethics to justify any means they appear to see fit to dismantle “systems of oppression”. For example, regarding Principle C: Integrity, they state, “we also read it as authorizing clandestine methods of civil disobedience to contest injustice (e.g., deception, evasion) when methods maximize benefits and minimize harm” (pg. 1224). This stretches the intent of the use of deception from research methods, a researcher pretending to be a student for example, to justifying outright dishonesty.

And of course, the special issue would not be complete without an article criticizing “good” psychology. Note, the use of “Critical” in this context is related to neo-Marxist “Critical Theory” and not critical thinking. Grzanka and Cole, 2021, make an argument for what they describe as “bad psychology”. They argue that “good psychology” (maintaining rigorous methodological, scientific, and objective standards) is a problem because it gets in the way of the radical political agenda of transforming society the way that they think is best. They state, “we contend that what is commonly thought of as ‘good’ psychology often gets in the way of transformative, socially engaged psychology. The radical, democratic ideals inspired by the social movements of the 20th century have found a voice in the loose network of practices that go by the term critical psychology and includes liberation psychology, African American psychology, feminist psychology, LGBTQ psychology, and intersectionality” (pg. 1335).

The authors do, conveniently, leave out the fact that the ideology underlying the radical social movements of the 20th century are attributed with mass murder on an unimaginable scale. Throughout the special edition, the argument is made, consistently, that this ideology, advocacy, and radical social transformation should be incorporated through all aspects of psychology: research, training, and delivery of clinical services.

How could the American people continue to trust the organization if this ideology is being actively promoted? What would psychotherapy look like within this ideological framework? I would argue that society would not and should not continue to trust APA if this continues. This is not sound, competent, professional, empirically informed psychology. This is Psychological Lysenkoism.

Critical Theory Ideas are Bad Psychology

APA has allowed, even endorsed, the miscommunication of psychological science that has the potential to negatively affect the mental health of individuals and society overall. Concepts such as implicit bias and microaggressions have questionable validity yet are so prominently displayed that they have the effect of gaslighting society. The net effect is to have people wondering if every interpersonal interaction is racist or bigoted and second guessing each encounter for intent and impact. These are reflective of the precepts and goals of CRT itself. The implicit idea is that almost everything is or can be racist is a central tenet of the ideology. From there, the goal is to then create the critical consciousness necessary to give rise to social unrest and revolution. The first paragraph of the intro to CRT, written for high school students, sets itself aside from traditional civil rights, and “questions” equality theory, Enlightenment rationalism, and neutral principles of constitutional law. Delgado and Stefancic (2017) state, “Unlike traditional civil rights discourse, which stresses incrementalism and step-by-step progress, critical race theory questions the very foundations of the liberal order, including equality theory, legal reasoning, Enlightenment rationalism, and neutral principles of constitutional law” (pg. 3).

An additional tenet is that the voices and “lived experiences” of marginalized groups ought to be accepted unquestioned. However, the hypocrisy of the framework is laid bare when the “voices of color” dissent from the prevailing narrative. Prominent examples are those of John McWhorter, Glenn Loury, Wilfred Reilly, Roland Fryer, Ayaan Hirsi Ali, Darryl Davis, Jason Hill, Coleman Hughes, Eric Smith, Ian Rowe, Thomas Sowell, and the list goes on and on. The same dissociation occurs with members of various marginalized communities when anyone of that community doesn’t toe to line with the ideological framework. The individual does not matter, only the prevailing ideological narrative and political agenda. Anything, or anybody, that interferes with that agenda is inherently loathsome. The most common response to any individual expressing skepticism or dissent is to label the individual (any applicable variation of -ist or -phobic) and should not even be allowed to have a voice!

APA Should Adopt a Pro-Human (All Humans) Orientation

In psychological practice, we should focus on the individual with inherent dignity, value, and careful consideration of how factors influence the individual. APA ought to return to a pro-human orientation. The “critical” movement denies the individual and views them as simply a representative of a superimposed group identity or combination of identities. This is antithetical to our field. The adoption of radical political ideology has even led to the resignation of at least one leadership role in protest. When we focus on our universal humanity, we can celebrate our differences. If not rejected as morally abhorrent as it is, then the American people would rightly lose trust in the organization and damage trust in our profession.

--

(1) “Critical Theories” (Critical Race Theory, most varieties of postmodernism, fat studies, etc.) have taken that name because they endorse deep skepticism of liberal democratic norms and practices that pervade … liberal democratic societies. I (this is Lee writing here) sometimes have a bit of fun with this by referring to critiques of Critical Theories as Critical Critical Theory Theories — i.e., turning the lens of critique that includes revelations of implicit, empirically flawed or moral dubious claims & assumptions back on Critical Theories themselves, as Ed Waldrep has done here with respect to APA.

#Eddie Waldrep#critical theory#critical race theory#cultural marxism#neo marxism#queer theory#postcolonial theory#lived experience#intersectionality#woke#wokeism#cult of woke#wokeness as religion#wokeness#psychology#human psychology#institutional capture#religion is a mental illness

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Right wing people when they discovered that they too could use postmodern philosophies to ignore reality for political gain

#critical theory#critical race theory#intersectionality#cultural marxism#intersectional feminism#whatever you want to call it#this one might be just for me#and that’s OK

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The strategies of the politics of the image has to take a very different and much less guaranteed route, in my view. It has to go inside the image itself – inside the image – because stereotypes themselves are really actually very complex things. It has somehow to occupy the very terrain which has been saturated by fixed and closed representation and to try to use the stereotypes and turn the stereotypes in a sense against themselves."

— STUART HALL, “Representation and the Media,” Media

Education Foundation, 1997

#media literacy#stuart hall#cultural marxism#marxism#media#media analysis#writing#writeblr#booklr#bookish#analysis#writing quotes#quotes#representation#my books reference 1997 heavily for a reason dootdoot

13 notes

·

View notes

Quote

If the social justice movement went by its actual name, young Christians would not have been lured into it. Because the social justice movement is actually CULTURAL MARXISM. There's no such thing as social justice, people. In fact, in the Bible, justice never has an adjective. There is justice and there is injustice, but there's not different kinds of justice.

Voddie Baucham

33 notes

·

View notes

Quote

The mode of production of material life conditions the social, political and intellectual life processes in general. It is not the consciousness of men that determines their being, but on the contrary, their social being that determines their consciousness.

Karl Marx, German Ideology

#structuralism#consciosness#solipsism#social construct#karl marx#marx#german ideology#marx 1859#1859#carl marx#philosophy#19th century philosophy#materialism#social construction#marxism#cultural marxism

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cultural Marxism doesnt make sense. Marxism is an economic theory, so cultural marxism if we take it literally would be the effects on culture under marxism.

Yet people use it to describe things like lgbt representation.

Their words are meaningless

3 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Prof. DiLorenzo: How Cultural Marxism Destroyed Education

0 notes

Text

“Unless we understand the dire nature of the threat now facing our nation due to the efforts of committed Marxist-Leninists now occupying positions of power and trust throughout America, we soon will very possibly be an easy target for those countries who envy and fear our successes—and freedoms.”

(From my blog archive)

0 notes

Link

Podcast Published: Aug 2, 2022

[..]

Steve McGuire: Anyways, maybe we start by just setting up what was the keynote about? What was your critique of it?

Erec Smith: Well, the keynote was at a conference called the Conference for College Composition and Communication. The keynote address, I'm forgetting the very long title, but it was, How Do We Use Language to Stop People from Shooting Us or something like that. And his overall argument was that white professors, white scholars are inherently problematic. He used terms like students of color feel suffocated by whiteness. And this idea that language is sold as something that will save our lives, but it won't. I don't know anybody who thought that language would make one bulletproof so I didn't really understand that either. I thought this did a little bit more harm than good. It didn't just demonize white people. It infantilized people of color. Scholars and students. So I went to the listserv and I asked, "Was this the best way to go about this? I think this was pretty problematic and we should talk about it."

That was not met with agreement. It was not met with a desire to talk. It was met with a desire to yell at me and not listen to my responses. That's for sure. And I realized something then. I realized that there is a particular narrative that is heavily founded on victimhood, infantilization, the oppressor/oppressed dichotomy. And that if you don't abide by it, then you are a bit of a pariah. There are sacred texts. I mean, John McWhorter's characterization of this as a religion is apt. There are texts you cannot question. There are people you cannot question. There is a party line you cannot steer from. And that's that. It is somewhat cultish. I like to tell my students emotional intelligence is it about not ever getting angry, it's about channeling anger into something more productive.

So that's what I did. The initial anger, which eventually became just amusement, but we can talk about that a little bit later on. The initial anger resulted in two books, several articles about the misguided nature of contemporary anti-racism. And a website and online journal called Free Black Thought. I have other things in the works right now, but those are the solid things. And it's changed my career. I had no intention of doing this stuff before that listserv, before that thread. No intention. And here I am, and I'm speaking all over the country about these things. I'm being asked to moderate very popular panels. And this is all because I'm pushing back against the contemporary mode of anti-racism in academia.

Steve McGuire: Right. Right. So you're not yourself just against anti-racism in toto, you just have a critique of certain contemporary trends within anti-racist discourse and action, I guess.

Erec Smith: Right. Right. And a lot of people will mischaracterize me as being against fighting racism, which makes no sense whatsoever. And the people who say that, I mean, this is why nuance is kryptonite tonight to woke ideology. It's got to be either or, or else their ideas fall apart. So to critique this version of anti- racism comes off as I'm against fighting racism. Right?

It can't possibly be, I don't like this particular strategy. I want to do this strategy. No, that's not possible at all. So my critique of anti-racism is the fodder for my last two books. One called A Critique of Anti- racism in Rhetoric and Composition, and one called The Lure of Disempowerment. The first describes the contention and issues around anti-racism in academia. The second is more prescriptive in that it is trying to provide a possible alternative to a lot of DEI trainings, which again are based on a oppressor/oppressed dichotomy and a lot of guilt and victimhood. So, yeah.

[..]

Steve McGuire: Interesting. Yeah. In the first of the two books that you mentioned, you propose an alternative approach to anti-racism that's based in empowerment theory. Could you maybe just describe how that is different from the current trends in anti-racism that you're critical of and what that is and why you think that could be a more productive approach?

Erec Smith: Well, I think current anti-racism, based in what I call, what others also call critical social justice, it necessitates victimhood, it necessitates infantilization, it necessitates disempowerment. The people in question have to be distinctly disempowered first and foremost. If they're not, then nothing else works. So you're already casting people in victim and oppressor roles before you even know them.

And that's wrong for obvious reasons, but it's also wildly disempowering. And so how do we do this in a way that doesn't infantilize some and demonize others, but empowers everyone? Because I do think that feeling empowered goes a long way in being able to accept other people. Because a lot of what's going on is that we project our insecurities onto other people. We project our fears on other people without even realizing we're doing that. So empowerment theory, what that does is help us be more self aware. It promotes metacognition, emotional self control, things like that. So that we can meet people where they are. And once we meet people where they are, we can have generative conversations about what needs to happen in ways that doesn't guilt people or patronize people or anything like that. And that's why I embrace empowerment theory. I dedicated a para ... I'm sorry, paragraph. A chapter to it in my book, A Critique of Anti-racism. And that chapter was expanded into an entire book called The Lure of Disempowerment. And so that's really what I'm driving these days.

Steve McGuire: Okay. Yeah. In the first book, The Critique of Anti-racism, in the introduction, you point to W.E.B. Du Bois as an example. And I was reading that and I was like, yeah, this is ... I mean, it's a really inspirational story. I wonder, is Du Bois ... He's an exceptional person. He's an exceptional intellect. He demonstrated exceptional courage. He clearly had a degree of self confidence. Is that the kind of thing that you're hoping for everybody to achieve? I can see somebody saying, needing to be like that just to get through the academy or something like that is a lot to ask somebody, if that makes sense.

Erec Smith: Well, you're not being like that to get through the academy. You're being like that to be like that.

Steve McGuire: Okay.

Erec Smith: And that's empowerment. The ability to not let somebody discourage you because of what their thoughts are about you. It doesn't matter. I often tell people, "Listen, if somebody calls me the N word in traffic, I don't care. I'm going to my tenured professorship to shape young minds and then research and write scholarship on topics I care about. And this guy is going to a bar at 8:00 AM. I win. I don't care about that guy's opinion." But I know that is a very unpopular disposition. So with empowerment theory, what I'm doing is saying you can create a disposition that can't be toppled.

You can do that. You can realize that somebody disagreeing with you isn't epistemic violence. You're not harmed. They just disagree with you. You can move on as long as people aren't in your way and blocking you. And if they are in your way and blocking you, then empowerment theory can help you better deal with that situation more strategically, more productively. In ways that don't indicate that your emotions are overpowering your ability to look at a situation for what it is. And I mean, that's what I see when I point to Du Bois and his attitude. I mean, he had that attitude in the 1880s. A black person in Harvard in the 1880s. If he could have that attitude then, then we cannot embrace victimhood now. Frederick Douglas had a similar disposition. When abolitionists would ask, "What should we do about black people?"

The black question. He said, "Don't do anything. Let them fall. That's how you learn how to get up." He was all about, "Just let us do this. We're adults. If you leave us alone, we'll handle it." And they didn't like that. They actually didn't like that. They liked the idea of minorities being the poster people for victimhood. I guess it helped them with their political aspirations as well. But Zora Neale Hurston's another one. She spoke out about this. She lamented the fact that the only role for black people was one of pity. And people were uncomfortable by the confident and successful black person. They didn't know what to do with that. They knew what to do with the downtrodden black person who needs white people to save them. And they knew what to do with that. And Zora Neale Hurston complained about it. In fact, she died in abject poverty because she had this position. And fought a lot, interestingly enough, with W.E.B. Du Bois. But that's fodder for a different conversation. But yeah. I point out Du Bois. I think he's a great model for dealing with things. He's a great model for what it looks like to be empowered. And I'm glad I put him in the book.

[..]

Steve McGuire: Yeah. Viewpoint diversity or intellectual diversity, a lot of people think that's a problem, say, in higher ed in general. I mean, you've got Heterodox Academy. And I think that probably a lot of people in various ways have found themselves in situations where they didn't think the way that people expected that they would think based on what they knew about them. Like I myself lean conservative, but I have a PhD, I've taught in the university. A lot of studies show there aren't that many conservatives in higher education. And so in terms of talking about politics, often I'll find myself in a minority viewpoint position. But I guess the question I'd like to ask you is how is it different or amplified when race is involved? And I could imagine it's a much bigger problem. Maybe one that is experienced on a more pervasive basis. I don't know. I'm just interested to know what your thoughts on that would be.

Erec Smith: Everybody thinks I'm a conservative because of these views. I wouldn't call myself that. I would say I'm left of center. I would say I'm somebody who embraces classical liberalism, which used to be something that both sides of the aisle could get around. I mean, it's the Venn diagram of Republican and Democrat, the center, what's classical liberalism. At least there was that. But that doesn't seem to be the case anymore. So people of all colors just assume I identify as a black conservative and I don't. That being said, at the college level ... And York College of Pennsylvania, where I teach, is not egregiously woke in any way. There are people here and there, but it's not a place that I feel uncomfortable walking onto. So there's that. But the field, the field of rhetoric and composition is a different story altogether. And yes ... Excuse me. I've been called a white supremacist by white people in the field. So that's how bad things are.

[..]

Steve McGuire: Interesting. You mentioned a few minutes ago that this has been something that you've dealt with your entire life, and I was just wondering if you'd say a little bit more about that. Is it that you've always had heterodox social and political views or interests, or what is it that put you in a position where you've had to contend with this so regularly?

Erec Smith: Well, I was always not being black correctly.

Steve McGuire: Okay.

Erec Smith: And I got this from white people as well as black people. So I've been dealing with this since I was a kid growing up in a predominantly white neighborhood and being reminded of that on a regular basis, several times a day. And then going to a more diverse high school and being shamed by the black students for being too white.

Steve McGuire: I see. Okay.

Erec Smith: So the combination of that, I didn't know it at the time, but that really set me on a path to where I am today, really, because I was very interested in why two people can come to the same conclusion for very different reasons, through very different values, attitudes and beliefs, very different ways of describing the world of using rhetoric on themselves and others who describe the world they see fit. A world in which I have to play a particular role. And that role can't be the smartest guy in the room, or that role can't be one of respect and virtue. It can't be one of optimism. An attitude of success. Wanting to follow your dreams and things like that. It was like both parties were saying, "How dare you like yourself? Don't you know you're black?"

They were both saying the same thing there. But they took different paths toward it. And that is something that can be addressed in rhetorical theory. How are we describing, what words are we using to describe this world? And how can we come to the same conclusion from apparently different places? Because we have similar ideas about ethos, about who we are in a grand meta narrative of society. And although we seem like we are fighting each other, we kind of abide by that narrative. We're all abiding by that narrative. So I was very interested in that. I didn't know the word rhetoric at the time. I didn't know the word discourse at the time. Ethos and things like that. But I would eventually discover it and realize this is where I belong.

Steve McGuire: Okay. So you're talking like, yeah, audiences have expectations of you right off the bat, just looking at you or hearing you speak or what they think they know about you and that sort of thing.

Erec Smith: Right.

[..]

Steve McGuire: It's like you were saying earlier, everything's binary. It's either-or. I'm wondering, what do you think is ultimately the source of that? It seems like it's just so crucially important that you agree, going back to this listserv debate, that students be taught or be allowed to express themselves in, say written assignments, I guess, through the African American vernacular English, as opposed to standard English. And the suggestion that it would be valuable to learn standard English is just instantly seen as anathema. You can't even debate that point because it would already be conceding too much even to consider it.

Erec Smith: Right. Yeah. They don't want to dignify it with a response.

Steve McGuire: Yeah. Right.

Erec Smith: Right. And the whole idea that expecting students of color to learn standardized English is inherently racist. That was also a part of the keynote address that sparked all this.

Steve McGuire: Okay. Yeah.

Erec Smith: So yes. That's part of it. Any kind of pushback will expose them for the flimsy ideas that they have. So they can't allow any kind of pushback. And so that's why you get the treatment that I got from the listserv. But there's something else going on as well. And this something else derives from what's called critical pedagogy, which derives from critical theory, which is something that derives from a Marxist think tank called the Frankfurt School. And there is a very clear thread between that school and what's going on today. When I talk about it, I sound like a conspiracy theorist, but it's true. It's all there. And what's there is the idea that the point is to transform society. Society is bad. That's not an argument. Society's already bad. When it comes to cultural Marxism or race Marxism, society is racist. This situation is already racist. That's already decided. These students are downtrodden and they feel bad and they're victims and we need to liberate them. That's already decided. There's no conversation about that. If you want to have a conversation about that, you're a bad person who doesn't get it or you're suffering from false consciousness.

Steve McGuire: Right. Yeah. Right.

Erec Smith: And those students who want to learn standard English, but they're black, that's false consciousness.

Steve McGuire: Right, right. Right. So you're not offering a counterargument that deserves to be considered, you've just made an error that needs to be pointed out to you.

Erec Smith: Right.

Steve McGuire: Yeah.

Erec Smith: Right.

Steve McGuire: But it seems like at the end of the day then, it's motivated by something other than scholarly concern to know what's true. It's motivated by politics or you reference McWhorter and his idea that it's a religion, which would make it a kind of spiritual problem or theological problem, not just a political one. But that raises the existential stakes for people who adopt these views to such a level that it literally is harmful or even heretical to hear or consider other points of view. Does that seem fair to you to say?

Erec Smith: Well, yes. Because, as is true for many critical theorists and pedagogues, the point is to change society. The point is to transform it. And this comes straight from ... Marx said, "Philosophers have been describing the world, but the point is to change it." I mean, that sentiment is still alive and well and in various corners of academia. So when that's the main goal, what education becomes is a trojan horse for those ideas. So you have the equitable math whitepaper. Maybe I shouldn't say whitepaper. Recommendation report that basically turns a math class into social studies. You have questionable accounts of history that are formatted that way to support this narrative that supports the need to transform society. And Lenin gave this advice in the 1920s. He said, "It's not enough to just learn these ideas. You have to learn math in so far as it supports communism." History in so far as it supports communism. And that's going on right now. There's a leader in my field who thinks that black students who want to write in standard English are immature and selfish. Because their success in acquiring standard English will help them go out and probably be better equipped for certain jobs and be happy and successful and therefore maintain the status quo.

Steve McGuire: Right.

Erec Smith: Right. Happy and successful people don't revolt.

Steve McGuire: Yeah. It's very similar to Marx. Yeah. You don't want people to be just materially satisfied enough that they're not going to go out into the streets. Interesting. You've said your career pivoted since 2019. You're tackling this stuff head on now. So you must at least have some small hope that pushing back and arguing against these ideas could have some positive impact in the academy. At the same time, it seems like this is the pretty strong wave or series of waves that's washing over a lot of places in higher education in the United States. And a lot of people don't have, I think, much hope at least for the immediate future that we can really successfully push back on some of these ideas. What are your thoughts on that?

Erec Smith: Well, I'm done convincing the wokest of the woke. Or trying to anyway. They are now a catalyst for my thoughts on viewpoint diversity. And they're also an opportunity to model what it means to push back on these people and why, and that we don't have to accept their absurd ideas. There are people out there who are listening to these things and saying to themselves, "I must be missing something. This makes no sense, but it's my positionality that keeps me from understanding what's going on." No, no. You're seeing it correctly. It's absurd. It makes no sense. You're seeing it correctly. And I want to confirm that. I don't just want to confirm it. I want to confirm it and meticulously explain why it's the truth. I just want to be that voice out there. I want people to know that not everybody's buying this crap. So long story short, I'm done trying to convince people. I am trying to "save" people who haven't fallen into the woke abyss yet or are still trying to figure out what's going on. That's what I'm trying to do. And I want them to know that there are people out there like them, like me, who they can reach out to.

Steve McGuire: Right. Yeah. Yeah. And you seem to have a bit of ... You mentioned earlier at the beginning, something about that you were angry, I think, earlier when you went through what you went through in 2019, but now you seem to be able to laugh about it, joke about it. It at least appears to me like you have no compunction about just calling it like you see it and saying it flat out with no apology. Is that the case and how did you get there?

Erec Smith: Yes. That is the case. And I got there from ... I mean, initially, the pushback, I was like, "Wow. They must not really understand what I'm trying to say. If they'd only listen to me." When I realized that they're just living in this world that makes no sense whatsoever, then they became jokes to me. And that's what they remain. So when people try to call me out and mob me again like that, I get excited. I'm like, "Okay. Yay. All right, we're doing it again. All right. What idiocy are going to say now? What absurd ideas are they going to throw at me now?" So I take that attitude about it now, and it makes all the difference. It really does. If you can point out their absurdities and do it in a way that is amusing and memorable, then you can probably get a little bit farther with these ideas instead of always being serious or stern all the time. I mean, that's important too. But I mean, when somebody says something ridiculous, point out the ridiculousness. Yeah.

[ Full podcast transcript ]

#Erec Smith#Free Black Thought#W.E.B. Du Bois#Zora Neale Hurston#antiracism#antiracism as religion#critical theory#critical pedagogy#false consciousness#cultural marxism#liberalism#liberal ethics#wokeness as religion#woke activism#cult of woke#wokeism#woke#oppressors#victimhood#victimhood culture#empowerment#infantilization#neoracism#long post#religion is a mental illness

10 notes

·

View notes