#interpret this however you want the author is not dead just ambivalent

Text

contributing to the vampire hua cheng fandom o7

pose referenced off of this / follow for more fafa :)

#started this for portrait practice but it turned out so good im obsessed#part of my efforts to draw him more inhuman#obviously claws teeth ears but also#i think maybe when he is being calamitous he should drip blood.#how sick would it be if he left bloody footprints and that was a sign he’s getting pissed#or maybe you start hearing thunder in the distance#so i guess this is not technically vampire hua cheng this is just my headcanon#interpret this however you want the author is not dead just ambivalent#tgcf#hua cheng#mxtx#tian guan ci fu#hob#heaven official’s blessing#crimson rain sought flower#hualian#tgcf fanart#天官赐福#花城#血雨探花#art#digital art#my art#vampires

313 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rakepick and her symbolism

Some of you might’ve already seen interpretations of Rakepick’s lioness Patronus (or you’re the authors of such posts), and I absolutely agree that this odd choice should make us wonder. However, I want to also focus on a bigger picture of the symbolism around Rakepick’s character – because personally, I find it quite fascinating. Once again, credits for involvement in research go to @wilhelminafujita. And it all started when I found the article Inside the magical ‘80s art of Harry Potter: Hogwarts Mystery saying:

(You can also see the concept art I posted some time ago: here)

They wanted to get it “absolutely right”. And you know what? They totally did. Her design is ridiculously well thought-out.

Let’s start with her pin: the Eye of Ra which is obviously a reference to her time spent in Egypt, and therefore creates also a connection to Bill’s future. But that’s not all. Here’s the meaning of the symbol itself.

When you look at the Egyptian goddesses mentioned above, one is interesting, in particular: Sekhmet, represented by a lioness.

And now, we finally know not only that Rakepick has a Patronus but also that its form is a freaking lioness. And just in case anyone forgot that a Patronus takes “the shape of the animal with whom they share the deepest affinity”, the devs made absolutely sure to show how closely it’s connected with Rakepick as she literally emerged from the light of the spell.

As people were pointing out before (see: 1, 2, 3), a lioness on her own is interesting as a symbol of motherly protectiveness. It also goes well with Rakepick belonging to Gryffindor: a House of courage, bravery, determination, daring, nerve, and chivalry. But with the addition of the symbolism behind her pin… It’s pretty incredible, in my opinion. Even her name, Patricia, is derived from the Latin word patrician, meaning "noble". It all just goes too well together to be a mere coincidence: it’s a deliberate and pretty detailed design.

When we first meet Rakepick, it’s easy to think: “What a bitch!” – and the game keeps convincing us that it’s the case. But if you really look at her, Rakepick is full of duality: violence and protectiveness, a warrior goddess and a goddess of healing. The colour red, so prominent in her appearance, is associated with rage, anger, danger but also love, passion, courage, and power. I wrote quite a lot in the past about the duality in Rakepick’s behaviour (see: here, for example). And yet, while I find it really fascinating, I’m also terribly worried seeing what they’re doing with her character, especially after the recent chapters…

I doubt that anyone from Jam City will read that, but if they will… Listen, Rowan HAS TO come back somehow. They have to. If you decide to be arseholes and keep them dead, though – I beg you, stop teasing us with Rakepick’s ambivalence. Don’t give her a lioness Patronus, don’t give her a Patronus at all. Don’t waste time on animating her visually gorgeous entrance in the Forest. Just don’t. Make her a boring, plain, murderous villain. Because if Rowan is truly gone, Rakepick could be dead as well. This IS NOT the story where you can have “grey” characters who actually kill kids in the name of the greater good. It won’t work for anyone. I still claim that you kind of ruined her character already since it’s just too extreme. Most people don’t care about the ambiguities I’m talking about here. And you know, in that particular case, I can’t really blame them. But some of us do pay attention to that, so for the sake of our sanity: you have to either tone it down or just commit entirely to Rakepick being evil.

I’ll never believe that she was always meant to be evil with all that symbolism and whatnot. It also simply doesn’t make sense from the story’s perspective. I said it many times before, but what was the point of wasting all that time on her? Just to introduce a murderer? Rakepick’s betrayal didn’t have any emotional impact as MC never trusted her and we weren’t allowed to declare otherwise, not really. At this point, there’d be absolutely no difference if she appeared right before the Portrait Vault. If Dumbledore was like: “Y’know, MC. I was thinking last night: how about I get you a professional Curse-Breaker or something? She should be here before the end of the week”.

I don’t know, I feel like Jam City had different plans for her, even if Rowan somehow survived. But if they decided to abandon that original idea entirely, they should stop taking from it as they please when it doesn’t make sense.

#long post#hogwarts mystery#hphm#hphm spoilers#patricia rakepick#madam rakepick#pro rakepick#jam city#symbolism#analysis post

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

Persephone in “Jasper In Deadland”

Thanks to a random comment from a friend on a Tumblr post, I only just remembered that there’s another musical with Persephone that lies somewhere in between “Hadestown” and “Mythic”: “Jasper In Deadland.” I saw it back in 2014 and I thankfully have an audio recording of the show (there was an official recording made in 2016 and they’re quite similar but it doesn’t have the dialogue bits). It’s functionally a modern teen-audience retelling of the Orpheus and Eurydice myth but the Underworld has been replaced with Deadland, a land that is a ultimately a mixture of different mythological underworlds.

When Jasper is in Deadland searching for his dead friend Agnes, he encounters a bunch of people and places from myths in the six-layered combo-Underworld:

There’s a boatman named Lester, not Charon. The river they’re on is the River Lethe from Greek mythology (the first layer) and serves the same function. There is a Mr. Lethe, as opposed to a goddess of the river as there was to the Greeks.

Mr. Lethe is the story antagonist (of the evil capitalist factory owner variety; think an evil Hadestown!Hades and the closest thing to Satan) and Mr. Lethe’s goons who follow Jasper around are Loki and Hel of Norse mythology.

A three headed dog (who isn’t referred to as Cerberus in my 2014 recording but is referred to by name in the 2016 recording) guards the second layer.

Osiris, the king of the Underworld in Egyptian mythology, is a club DJ in the city layer, the third layer.

The club is called Helheim, the domain of Hel in Norse mythology and obviously where Hell comes from.

At one point Lester appears again and mentions that the only living souls in the Underworld are Orpheus, Lazarus, JC (I think it’s easy to guess who that is), and Jasper thus bringing in Christian mythology. The comparisons between Jasper and Orpheus are mentioned frequently throughout the show from this point.

Ammit of Egyptian mythology guards the fourth layer and weighs hearts along with “Blind Justice” (it’s been too long for me to remember what that means).

The fourth layer is some sort of gulf, but I’m not sure if that comes from any myth.

In the gulf, they meet Beatrix from The Divine Comedy who in this is part of the Elysium transit authority who drives a vehicle called Purgatorio.

They are brought to Mr. Lethe’s factory, which seems to be most like the Christian Hell or Tartarus, and there are Sisyphus, the Danaids, Brutus, and the fallen angel Luke, who’s the foreman.

They get to Elysium from there, and Jasper meets Eurydice in a fever dream.

In this musical Pluto and Persephone dwell in Elysium, the sixth layer and it’s implied that they rule that layer (I couldn't find an image of them from the show I saw but they were both wearing traditional Greek garb possibly in pink and burgundy or light green and black or something). It’s a little unclear what their relationship is to Mr. Lethe but it seems like everyone in the musical more or less runs their own specific domain without really stepping on anyone else’s space. It drives me nuts that they use those names since Pluto is the Roman name and Persephone is the Greek name (of unknown origin truthfully) so I’m just gonna call him Hades. At the beginning of their introduction Persephone is saying goodbye to Hades and he is begging her to stay longer and calling her snowflake. Lester comes in as her attorney to makes Hades sign their annual divorce contact. Persephone tells him that the year was “almost bearable” (and calls him Plutes, which sounds kind of gross to me but okay). It’s unclear whether she is messing with him or being honest but their relationship comes off as very unbalanced. Hades is very clearly in love with her and her feelings towards him are less clear. While I kind of like the idea of Persephone being so powerful because of how it recalls very old earth goddess/male consort ideas, it reads as kind of sad. There’s no mention of the origin of their relationship, which could have at least made it seem a bit more like maybe Hades was still repenting for kidnapping her or something but nope. She’s just kind of weirdly ambivalent to him while he worships her.

When Jasper and Agnes show up Hades is kind of annoyed to see him since he’s been causing such a ruckus but Persephone is amused by his presence. I support both aspects of this characterization. However, they are in agreement that Jasper needs to go back to the world of the living but that Agnes can’t. Jasper says he wants to trade his life for Agnes’ and Hades says he will allow it. An interesting change from the 2014 show to the album recording is that “Lifesong”, a song originally by Jasper about him giving up his life for Agnes, is now a Persephone song and then partially repeated by Jasper in the following song “The Trade/The Swim”. The ideas in the song about bringing life and the end of life vibe very well with her purpose so I understand the change and always support the idea of Persephone getting more screen time.

After Jasper’s declaration, Persephone steps in to say that maybe an exception can be made because she sees herself in them in how she too wants a “meaningful life.” This “meaningful life” line is actually not on the album so I wonder if they cut it because it feels completely random without the characterization to back up what she means by that. It could hint at the idea that maybe part of her ambivalence to being underground has to do with her not having as much work to do as she would on earth, but this is purely speculation.

Persephone offers to stay one more day with Hades if they are allowed to both go back and Hades is comically pumped. She makes a comment about how it’s hard for the first few millennia but you get used to it (seemingly she means she’s used to Hades or possibly his enthusiasm?). This may have also been cut from the show by 2016 because it’s not on the album but I don’t know. It is kind of startling that after millennia, this is still the dynamic between them. I can’t say I’m a fan.

Persephone gives them instructions to get out and later when they get above ground Jasper attributes the snow in spring to “an act of goddess.”

Overall, I like how powerful Persephone is in this interpretation but I can’t say I like sitcom!husband and sitcom!wife as a choice for her relationship with Hades.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thoughts on House of X #6

The penultimate issue!

While You Slept, the World Changed:

Before I get into the content, let me say that I think Hickman et al. really brought it with their two final issues, which are some of the best of the miniseries.

Showing Hickman’s love of circular storytelling, we flash back to the speech from the very first page of House of X #1, where Xavier announced the formation of Krakoa. The always-frustrating timeline is cleared up a little: Xavier’s speech happened a month ago, although we know from that same issue that work had been going on on Krakoa for “months” before the announcement - more evidence that the schedule was important.

Despite this all of this preparation, Xavier takes a moment before the speech to ask Moira and Magneto to join him for this “leap of faith,” which requires “total commitment.” (Which is interesting, given Namor’s questioning of same.) Moira agrees quickly, but then hangs back and watches, as is her wont (as we’ll see in Powers of X #6).

By contrast, Magneto makes a significant shift from his earlier pledge of unrelenting accountability to burying the hatchet completely (I love how “all the anger at the other’s relentless ideology and unyielding persistence” so perfectly describes both men) and promises his complete support (and possibly more, depending on how you interpret the hand-on-hand-on-shoulder panel) going forward. That’s a big moment for the two of them.

And then we get Xavier’s speech in full, which I’m going to do my best to annotate.

“Humans of the planet Earth...I am the mutant Charles Xavier and I bring you a message of hope. ”

The first thing I’ll note is that we’re already seeing a rather significant change in Xavier’s behavior: for decades, Charles Xavier refused to come out of the closet as a mutant even when asked directly, and only did so in New X-Men when possessed by Cassandra Nova. Here, he’s straightforwardly describing himself as “the mutant Charles Xavier,” putting his group identity before even his name.

Secondly, there’s an interesting tinge of classic sci-fi in the way that Xavier addresses “humans of the planet Earth” - it’s very reminiscent of The Day The Earth Stood Still - and I wonder whether part of this has to do with the so far largely unspoken Krakoan ambition of beating humanity to the Moon, to Mars, and the stars themselves.

“In the coming days, you will learn of several far-reaching pharmaceutical breakthroughs that have been discovered by mutant scientists. These drugs extend human life, heal disease of the mind, and will prevent - or cure - most common maladies. Influenza, Alzheimer’s, ALS, many cancers...gone. Overnight. These drugs will make life on this planet...better. Remarkably so.”

First, this is very much of a part of Hickman’s technocratic futurism from his F.F run, which I have to imagine often leads to a bit of frustration with the editorial mandate not to use super-science to make the world unrecognizable.

At the same time, I’m all the more convinced that the point of this proffer (in addition to buying U.N votes and diplomatic recognition) isn’t to mess with human biology - I think the drugs actually do what’s advertized, rather than mind-controlling people or activating the X-gene - but rather (according to what we learn in Powers of X #6) to dull the drive to achieve post-humanity, solving humanity’s problems but leaving the source out of their hands. This is a theme that featured quite heavily in the finale to Hickman’s Transhuman.

“All this...we have made for you. In the past they would have been a gift. Something freely given by me -- to you -- because I believed it would create harmony between our two peoples. That was my dream -- harmony -- but you have taught me a harsh lesson: that dream was a lie. You see, all I ever wanted was peace between humans and mutants. All I ever wanted was to love you and for you to love us.”

Here’s a great example of how comics can use text and imagery in different ways. Visually, what this page shows us is different levels of humanity: ordinary people in a hospital room, who see Xavier’s speech as a message of hope, the promise of deliverance from disease; a board room full of businessmen who probably see either opportunity or competition, depending on their market position; and a situation room of national security types who represent human power structures that have always viewed mutants as a threat.

At the same time, I think the text is an answer, if not a rebuke, to those fans who’ve been decrying Charles Xavier as acting “out of character” or spinning conspiracy theories about how it’s actually the Maker or the like. This is clearly the same Charles Xavier, who has come to change his mind about his vision of society, because he’s seen how humans have responded over again. (I think it also gets at one of the problems of grounding the X-Men in a “dream” of harmonious co-existence when genre conventions prevent that dream from ever coming to fruition. Especially given how the serial nature of comics leads to repetitions of “anti-mutant hysteria,” it’s not surprising how much of the fandom have shifted to a “Magneto Was Right” perspective.)

“We wanted to save you -- and we did, many times -- but in return, all you did was stand by while evil men killed our children. Over 16 million of them. So there will be no gift...for you have not earned it. We will -- however -- let you pay for it. In return for two things, we will provide you with the means to have a better life. One without pain or suffering and full of hope -- and it will cost you so little.”

Here, instead of constrasts, the text and images are working in concert, with the art giving pointed examples of whom Xavier is referring to - pointing to the Avengers as “stand[ing] by while evil men killed our children” (given that the Avengers tend to specialize in threats to the planet, but have had a decidely mixed record when it comes to threats to mutants specifically, to say nothing of the fallout from the Scarlet Witch’s actions), or the Fantastic Four as having “not earned” his “gifts,” given that the FF haven’t exactly been at the forefront of applying scientific advancement to specifically mutant concerns. Similarly, Doctor Strange was willing to brave the dangers of hell to bring the city of Las Vegas back from the dead, but didn’t do the same for the victims of Genosha.

At the same time, it becomes clear that what Xavier is getting at isn’t just direct complicity in anti-mutant violence, but the broader systemic problems of human apathy towards anti-mutant violence. (Although, to be fair, he’s bringing this up as, essentially, emotional blackmail to justify his economic policies and his political demands.)

On a different topic, it’s interesting that Xavier is offering something of a utopia for humanity - “a better life...without pain or suffering and full of hope” - but may instead be planning to put humanity inside a walled garden where they will be cared for but kept out of mutant-kind’s way.

“First, you must accept the island of Krakoa as the nation-state of all mutants on this planet. We will happily go through the same process as any newly formed nation with the U.N, but there is an expectation that our sovereignty will be recognized. Second, all mutants -- by birth -- can claim Krakoan citizenship. And with that citizenship, we expect a period of amnesty. So that those who have been singled out as criminals -- or punished and imprisoned by humans -- can overcome man’s bias against mutants.”

So here we get Xavier’s main political ask: international recognition of Krakoan sovereignty, mutant citizenship, and amnesty for mutants in prison.

It’s clear from his tone, however, that Krakoa is going through the “same process as any newly formed nation” mostly as a formality, with “an expectation that our sovereignty will be recognized” - both because humanity needs what Xavier is offering and the unspoken fact of mutant power.

One thing that caught my eye is that the citizenship/amnesty isn’t just a one-for-one copy of Israel’s law of return; given the heavy focus on human judicial system’s “bias against mutants,” it also borrows heavily from the 1966 platform of the Black Panther Party, which called for “freedom for all Black men held in federal, state, county and city prisons and jails,” because they had been denied a trial by jury of their peers.

“From this day forward, mutants will be judged by mutant law, not man’s. These are our simple demands, and they are not negotiable. In return for making our lives better, we will do the same for you. And if you find yourselves asking, who are these mutants to think they can dictate terms to us? We are the future. An evolutionary inevitability. The Earth’s true inheritors. You closed your eyes last night believing this world would be yours forever. That was your dream. And like mine...it was a lie. Here is a new truth: while you slept, the world changed.”

Here’s where we get a firm statement of mutant-kind’s manifest destiny, although how accurate a description of “evolutionary inevitability” it might be is up for debate, given what we learn about Moira’s Sixth Life in the next issue. No wonder that Magneto is eating it up, but Moira seems more ambivalent.

One important thing to note: as the art demonstrates, ORCHIS is very much in operation when Xavier makes his announcement. Rather than being a response to a more militant and separatist Krakoa, their motivations are much more driven by eugenic fears of demographic replacement, which is way less defensible.

Quiet Council of Krakoa Infographic:

In the wake of Powers of X #6, we now have to ask ourselves whether the (un-elected, possibly temporary) Quiet Council is, if not a Potemkin government (this would be a bit much, given what they get up to in this issue), but perhaps not the only locus of authority on Krakoa.

In addition to continuing the naturalistic themes of Krakoa, I wonder whether the Autumn/Winter/Spring/Summer designations suggest a kind of rotating chair system for a council in which all are supposedly equal...but who is primus inter pares? Xavier is acting as speaker, setting out the agenda and moving the action along, but he’s not the only voice in the room - a sign that he is sharing power to a significant extent.

So let’s talk about the membership of the Quiet Council:

Autumn: here we have the three ideological leaders whose ideas have led to the formation of Krakoa (although Apocalypse’s contributions are less public), and potentially Moira’s exes (although we never learn whether Moira was romantically involved with Magneto in her Eighth Life).

Winter: is “where we parked all of the problem mutants” other than Magneto. Mostly, this seems to be on the basis of both necessity and “better inside the tent pissing out than outside the tent pissing in.” One question I have is whether Exodus, as someone who used to basically worship Magneto, is a vote that Magneto can count on, since clearly he and Sinister aren’t on the same page, and Mystique is very much on her own.

Spring: here is Emma’s quid-pro-quo, and a recognition that the economic and foreign policy might of the Hellfire Corporation has to be represented within the governing structure of Krakoa. Given the structure (down to the very seating), I have to think that Xavier and Magneto had always planned for the third vote that Emma demanded. It’s also quite notable in later deliberations how limited Sebastian Shaw’s influence is on the Council.

Summer: as we might expect, given who’s extending the invitations, Xavier gives three seats to “my children,” which gives Xavier at least four votes that he can count on - although Ororo, Jean, and Kurt clearly have their own minds and priorities. As the Krakoan national project continues, counting votes will only become more important.

Speaking of which, we can’t forget about Krakoa and Cypher. While not formally one of the twelve, they are nonetheless a powerful influence who have a voice if not a vote on the Council. And ultimately Krakoa’s voice is quite loud, because the whole enterprise cannot happen without its consent.

The Great Captains:

So here we see the division of civilian and military government, with the “great captains..assum[ing] the responsibility of defending the state” during “times of conflict or war.”

The more curious question to me is what counts as a “state-related excursion” - it would seem to cover X-Men missions like the one at Sol’s Forge and at the ORCHIS facility in X-Men #1, but does it mean that Kate Pryde wouldn’t be in charge of her own vessel if Bishop steps on board? Does it cover X-Force clandestine operations, or would plausible deniability be important? Who does X-Force report to?

Cyclops as first among equals makes sense, although it does raise a question of what happens when you have two other captains in the field.

So Bishop makes sense as a head of whatever the name of the agency in charge of resurrection-related investigations is (possibly X-Factor), but I was surprised to see him show up in Marauders #1.

I wonder what Magik’s role as a Captain is supposed to be, especially since it seems she’ll be heading off to space in New Mutants. Down the line, I’m going to guess she’ll be involved in Krakoa’s version of Inferno, but what’s her intended role supposed to be?

Finally, what’s Gorgon’s role as Captain supposed to be.

The First Laws of Our Nation

Before I get into the content of this section, I want to talk about the beautiful panelling here that starts wide, shrinks down to the nine panel grid as the political debate intensifies, and then opens up again once the decision is made.

Similarly, I like the use of the two key symbols: the X of the chairs and the sigil on the ground (secular authority), Krakoa’s face looming over them all like a heart tree (spiritual authority)

Given what we learn in Powers of X #6 about why various council members was chosen, describing three of the four seasons as “family, friends, and allies” is highly ironic.

Sabertooth is removed from watery confinement - which, if Krkaoa can just hold people in water bubbles for an extended period, why isn’t that the punishment used late? - and Kurt sets an appropriately Biblical tone by noting that “our first bit of business is the oldest kind on this planet...judgement.” (Appropriately for Kurt’s themes, the judgement in question also centers on how to punish the first murder in this new land, and ends with exile.) Also, for those of you keeping track of how much Krakoan justice accords with human conceptions of justice, I will point out that Sabertooth comes out of the bubble threatening his judges/jury, which is never a good look for a defendant.

So let’s talk about the trial:

One of the things that jump out to me immediately is that it’s interesting seeing Magneto in the role of an idealist - “this is the establishment of a nation...and I would have it be one of laws.” - whereas Xavier’s acting as the pragmatist, acknowledging that “I cannot say everyone here best represents the ideals of what any society should be based on,” but that they have to do the best with what they’ve got. Ultimately, I think this is a tension at the heart of all national projects.

Meanwhile, we get precisely three speakers in before conflict erupts: Sinister is a camp shit-stirrer who (publicly, anyway) really only partakes in the meeting to poke at Xavier and Exodus. Meanwhile, showing how little bloc voting there will be in the “problem mutant” camp, Exodus goes right for direct threats, prompting Sinister to propose criminalizing “mutant-on-mutant violence” (again, the political resonances here are obvious), not because he believes murder is wrong but because he’s enjoying trolling Exodus.

Showing how much Krakoan technology and the...unique worldviews of the Council members are going to produce new forms of political philosophy, Aopcalypse opposes Sinister’s motion, because he doesn’t think it should be “a crime to kill someone who cannot be killed,” since killing mutants is now a non-lethal way of testing them for social Darwinian worthiness.

This clearly does not track with Storm’s morality, and in a rare moment in HOXPOX where we get to see Jean Grey operating as a forceful political presence, she uses Storm’s interjection to pivot to an appeal to “the highest of ideals” (perhaps aiming her words at Magneto as well as her fellow X-Men) that it should be the “highest crime...killing someone who cannot come back.” (This is more in line with her more recent appearances in X-Men: Red.) Thus, the Second Law of Krakoa is established...without actually taking a vote. It seems that the Council operates on the basis that any proposal not actively objected to becomes law, which I imagine the political scientists out there have some thoughts on.

Before the law passes, Mystique raises the question of self-defense against human aggression (which fits her first X-appearance nicely). Showing how much his earlier views have shifted now that he’s operating in the context of a mutant nation-state, Magneto distinguishes between “murder” and killing “done in defense of a nation,” and while that question is formally tabled, it does suggest an exception for formal armed conflict at least in the founder’s intent.

Supporting my theory that he’s going to be the de-facto Chairman or Speaker, Xavier not only drives the agenda (although he’s not alone in this, Magneto is definitely acting in this capacity), but also makes sure to “call the question,” deciding when proposals become law as long as no one objects.

Another point wrt to the justness of this process: well before he’s found guilty, let alone sentence is passed, Sabertooth threatens murder and cannibalism against his judges...which isn’t a persuasive defense against murder charges (even if he’s just threatening the murder of mutants...which isn’t legal AFAWK, just not as illegal as the murder of humans.)

A nice bit of character work, and another rare rmoment where we see Jean’s power in action, Emma and Jean collaborate to silence Sabertooth’s ranting.

With the Second Law established, and Sabertooth’s trial technically in abeyance, the Council moves on to “any new business.”

As we might expect from a neoliberal robber baron, Sebastian Shaw calls for “property rights, wealth, currency,” to be legislated for next.

In an interesting turn of events, Doug Ramsey interjects that “Krakoa is alive. Not a place, or a biome -- a person.” Krakoan (real) property rights will have to have a decidedly non-capitalist orientation, because as we see further in Marauders #1, in addition to not having rights in the land, you have to ask for Krakoa’s consent in order to build grow a house.

In a development I didn’t see coming, Storm takes the position that that mutants can still own property, but “it has to be...out there...in the world. No one has said we have to run from it.” This is somewhat more capitalist than I might expect from Storm, but it does make sense that someone with her particular entanglements in the wider world would take a less isolationist position. This raises an interesting question: if mutants own property in a sovereign nation, and they decide to plant Habitat flowers on their property, does that make that property now part of Krakoa?

Doug’s position gets supported by Exodus (in a characteristically religious tone), and Xavier once again calls the question, creating the Third Law of Krakoa. For those of us keeping track of the colonial theme, it is interesting that this largely European-led nation state has taken a legal position on land ownership that’s much more associated with indigenous peoples.

Befitting her role as the true power in the Hellfire Trading Company, Emma Frost tables the discussion of economic legislation, due in no small part to it impinging on Krakoan diplomacy and international economic policy.

With a decidely mocking air aimed at her son, Mystique shifts the agenda from the secular to the sacred. After a moment’s thought, Kurt who fires back with the original “manifest destiny” out of Genesis (the first creation), and we get the First Law: “make more mutants.” In addition to continuing the very horny feel of the issue, this law raises a set of interesting questions about Krakoan attitudes with regard to the right to choose, access to family planning services, and sexuality - although as Hickman has pointed out, the implications of an egg-based system for (re)growing people point in completely different directions. Why assume Krakoa will follow human social mores in any area?

With the fundamental laws established, the Quiet Council can now decide how to apply them to Sabertooth:

In an example of how subtly powerful agenda-setting can be, Xavier makes the question of voting guilty or not guilty a question of “making an example...that no one is above mutant law” or “giving you one last chance.” Fitting his somewhat collectivist bent in Powers of X #1, he frames this question not in terms of the civil rights of “Mr. Creed,” but in terms of how the decision “benefits our new society.”

While it doesn’t quite settle the post facto question, Magneto argues that Sabertooth’s killing of the Damage Control guards violatted the “strict instructions” he was given when Magneto dispatched him on the mission, making it not merely a question of the First Law but also of obedience to the chain of command. Apocalypse, who knows something about managing an aggressive workforce, agrees.

Sinister and Exodus, for once, are on the same page, and while Mystique ultimately goes along with the emerging majority, her body posture and dialogue suggests a degree of internal conflict - after all, she was the one leading the mission, so some responsibility falls on her shoulders.

Turning to the X-Men side of the room: as befits his spiritual role, Kurt feels shame for not turning the other cheek, Jean takes a moment but is more assured, and of course Storm has no problem with a bit of divine judgement.

Continuing the trend of divisions among the Hellfire Club, Emma is all about getting rid of Sabertooth, while Sebastian goes along with the emerging consensus because he doesn’t care.

And once again proving that a defendant representing themselves is always a bad idea, before all the votes are in (and we don’t know whether Krakoan juries require a unanimous verdict) or the sentence is given out, Sabertooth threatens familicide of the Quiet Council. Not exactly a strong argument for leniency, since Sabertooth hasn’t exactly been pleading innocence at any point.

Finally, Doug asks Krakoa to bring the hammer down, and Sabertooth is dragged down to hell put into an oubliette. As Xavier explains, “we cannot send you back into the world” (because Sabertooth is a serial killer who can’t restrain himself, and Krakoa just promised the world it would hold mutants accountable for their actions), they won’t jail him because “we tolerate no prisons here” (this seems a technicality), they won’t kill him, because seemingly the “resurection protocols” are non-optional (which is interesting, given what we learn about Destiny in the next issue), and so they “exile him.”

One interesting question: given the resources available to them, why is it necessary to leave him “aware but unable to act on it” rather than have him be unconscious during stasis? My guess is that Xavier wants to motivate Sabertooth to “redeem” himself down the line.

And then finally, we get Xavier’s concluding statement, where I think Hickman’s views on nation-states (“it’s distasteful, I know, this business of running a nation”), the proper attitudes one should have about holding and exercising political power (”I pray we never get used to it...never grow cold from it...never learn to love it”), and even parenthood come through.

Just Look At What We’ve Made:

But in the meantime, the council emerges to what almost everyone has analogized to the Return of the Jedi celebration: not only do we see bonfires and fireworks and a riot of color everywhere, but we see mutants flying around, using their powers, for the first time really feeling that they can live as mutants without fear for their lives.

As the Quiet Council walk down the steps, we see some of the reasons why and the consequences: the Five party as one, but near them we see the formerly dead raising a glass with the living. And echoing Magneto’s earlier statements about how Krakoa will change the way mutants see their own powers, we see Siryn and Dazzler combining their powers for the purposes of culture rather than warfare or high tech.

Xavier’s final message is that the Quiet Council will work like hell to ensure that the next generation of mutants “sleep in soft fields of lush green, staring at the stars and dreaming of a future where they hold those stars in their hands.” Once again, a sign that Krakoa’s manifest destiny lies in space, a common theme of Hickman’s from his FF run. As this happens, we see three of the O5 goofing around (I’m surprised how many people didn’t notice that Bobby had frozen Warren’s drink while he wasn’t looking), and Exodus leading storytime with the children as Sinister watches in the background.

But that’s not what people are really here for - as nice as it is to see Broo and Synch and Skin and Pixie, what people really care about is the Jean/Logan/Scott panel. As the now infamous architectural diagram in X-Men #1 makes very clear, this is not a case of a mere open marriage: the most famous romantic triangle in X-Men history is now a throuple, founded on the principle of beer and tummy rubs.

Almost as exciting for much of the fandom is the next page, where Jean goes to make peace with Emma while Scott hangs out with Alex. One of the big questions going on is what Emma’s role is in the polycule, since she doesn’t seem to be living at the Summer House. My guess is that Emma is “part of it” (to quote David S. Pumpkins), but may only be with Scott, and definitely would refuse point-blank to share communal living quarters with Logan. We will have to wait for more evidence to be sure.

And so we end with Xavier and Magneto looking out over the celebration, taking a moment to feel (rightly?) proud of “what we have made.” And yet, all is not well, because Apocalypse, the third ideological force who (through Moira) helped to create Krakoa, broods on what he lost when Krakoa was born.

Krakoa Infographic:

With Krakoa now extant as a nation-state, we get one more infographic...that shows us that there is a Krakoa Atlantic to go along with Krakoa Pacific. This points to an important truth about this new polity - it would be a mistake to see Krakoa as an island nation like Genosha or Utopia, because the nation of Krakoa exists wherever the physical entity of Krakoa exists. It’s in the Pacific and the Atlantic, it’s on the moon, it’s on Mars, it’s everywhere a Krakoan flower has been planted. Which makes it a post-geographic power.

So what’s on Krakoa Atlantic?

The Pointe is one of Xavier’s Cerebro back-up locations, so that an attack on Krakoa Pacific won’t destroy the database.

Danger Island is the X-Men’s new and expanded training facility.

Transit allows for instant transportation between Pacific and Atlantic to allow the X-Men to respond to a threat to either island or cradle, and possibly a final keep to fall back to if everything else is lost.

And finally we get one last map of Krakoa (All), and there’s a lot we don’t know about these locations:

The House of X and the House of M are Xavier and Magneto’s residences, and the location of one of the Cerebro “cradles.”

The Arbor Magna is the big tree where the Resurrection system is located in/on.

The Arena we don’t know anything about, but from the name it suggests that it’s a combat-oriented location, either for training or for entertainment purposes.

The Akademos Habitat is almost certainly Krakoa’s educational facility that Jean mentions back in House of X #1, but the fact that it’s a Habitat is interesting, because a Krakoan Habitat is a ”self-sutained environment” of its own that is “part of the interconnected consciousness of Krakoa,” and I had thought that having a Habitat on Krakoa itself, as opposed to one out on the moon or Mars would be redundant. My guess is that this is meant to provide an additional layer of safety to the next generation of mutants.

We saw Transit back in House of X #1, this Transit location is the Grand Central Station for Greater Krakoa, linking all gateway locations together. Yet another sign that, for Krakoa, their nation has a different conception of distance.

The Oracle is, I would guess, probably one of the Krakoan Systems, most likely either Sage’s or Beast’s part of the system.

I don’t know what the Grove is supposed to be, but given its proximity to the Akademos Habitat, I think it’s supposed to be a living space, possibly just for the young and possibly not.

The Cradle, it turns out, is just a cradle.

The Resevoir could be that lagoon we saw back in House of X #1, which would make sense if the Wild Hunt is a nature preserve, because animals love to congregate at watering holes.

The Carousel’s name suggests it’s an entertainment facility.

We know what Bar Sinister is from its last appearance; it turns out that Sinister recreated his little island Edwardian eugenics nightclub on Krakoa. Interesting that it’s locsated so close to Transit; maybe Sinister wants to be able to make a quick getaway.

Speaking of the fruits of faustian bargains, it turns out that the quid-pro-quo for becoming the economic engine of a nation is that the Hellfire Trading Company gets a whole Hellfire Bay to itself as its headquarters.

Red Keep is almost certainly Kate Pryde’s new pad, which is conveniently ocean-ajacent for our newest mutant pirate privateer queen.

Blackstone is Sebastian Shaw’s Gilded Age “gentleman’s” club.

The White Palace is naturally Emma’s boudoir, complete with buzzsaws and spikes.

The unnamed location 18 is clearly Moira’s No-Space.

18 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi, I just recently found your blog and it's amazing! I'm so happy there are still people there are as invested as I am in the Animorphs series! I especially love your Adult AU and your analysis of the books. In fact I was reading one of your posts where you said that Cassandra Clare's book glorify violence - if I'm remembering correctly - and I was curious if you could expand on that. If you prefer you can message me privately since this is strictly an Animorphs blog. I hope I'm not bothering u

No bother at all. I sometimes feel like I spend half my blog space whining about how every other book on the planet is inferior to Animorphs, which isn’t actually the kind of vibe I’m going for. I SWEAR I LOVE YA SF. Just… Not Mortal Instruments. I’ve tried. I tried so hard to like that series. It is objectively well-written and creative. I just… I can’t with Cassandra Clare’s work. I can’t.

First of all: a confession. I’ve only ever read City of Bones, City of Ashes, and about half of City of Glass, and then several different issues (the glorification of violence, the glorification of “slender” or “skinny” bodies, the way Jace’s Freudian Excuse gets used to let him get away with all kinds of bad behavior, the borderline-pathological worship of True Love in City of Ashes) conspired to drive me away from the series as a whole. So I don’t actually know if Clare improves in the last 80% of the series. Thus everything I say has that big honking grain of salt.

However, I do take issue with the way that, from what I’ve seen, the Mortal Instruments series portrays violence. Individuals are portrayed as all good or all bad (literally, they’re on the side of the angels or else they support demons) and—from what I’ve seen—there are literally no good demons, nor are there angels worse than “morally grey.” This Manichaeisan worldview (which I think is no accident given the overtly Christian overtones of the series) basically justifies pretty much any acts of violence on the grounds of “they are bad and we are good and therefore pretty much anything we do to them is good, regardless of the means we use to get to that end.” One extension of this principle which pops up again and again and again with regards to the Shadowhunters is that Might Makes Right. Clary is the best at coming up with new runes to kill demons, which is a sign she is the best good; Izzy is the best at stabbing demons very dead, which is a sign that she is good too. Morality comes about by way of violence in that series.

It’s troubling because it glorifies war as “we are the good guys wiping out the bad guys” and utterly dehumanizes the bad guys in the process. Given that we live in a world where pretty much any group can be potentially cast as “the bad guys,” and that we as humans have an implicit bias toward casting ourselves as “the good guys” no matter what group we belong to… It can reinforce bad behavior. To say the least.

Case in point, the first scene in the series is one of Clary witnessing a major fight between (apparently) several children her own age, who are using deadly weapons to launch all-out attacks against each other and (again, apparently) succeed in killing at least two individuals at the end. The narration doesn’t focus on her shock or horror or utter terror; it spends a long time dwelling on how cute Izzy’s dress is and how nice Jace’s cheekbones are and how cool they all look swirling around with their magical weapons. (And slender bodies. Can’t ever, ever forget to mention that every single one of them has a slender body. I confess that’s the #1 pet peeve in the writing that drove me away from the series.) I’m going to go out on a limb and suggest that Clare has probably never witnessed a real fight, or even a video of a real fight, because this is not only unrealistic (real fights are short, chaotic, hard to interpret, and incredibly disturbing—kind of like how they’re described in Animorphs) but it also suggests that violence is cool.

Meanwhile, I don’t want to suggest that Clare is by any means the only author with this problem. There was a great article (which I have since lost—I’ll have to send a link if I find it) which pointed out that American Clinton supporters and American Trump supporters and American independent voters all cast themselves as the Rebel Alliance in Star Wars and cast their political nemeses as the Galactic Empire. Because it’s easy to do: the narrative of Star Wars dehumanizes the stormtrooper enemy (although I could have cried with happiness when Finn took his helmet off in the latest film) while glorifying the individuated, special, blessed-with-magic heroes. It literally says that there is “light” and “dark,” and that the light is justified in (for instance) blowing up a space station with dozens of prisoners of war and possibly hundreds of innocent sanitation workers on board, just as long as doing so advances the cause of the Light. Avengers, Doctor Who, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Supernatural, and a simple majority of sci-fi/fantasy suffers from this problem.

I also specifically said that Clare doesn’t so much glorify violence and other troubling content as much as she fetishizes violence, which I do view as a problem specific to Mortal Instruments. It leads to this attitude of “people did bad things to me, therefore I can do bad things to [totally unrelated individuals].” Clary nearly forces Alec to out himself to his parents (which, I admit, hit all of my own personal “NOPE” buttons when I was reading the series as a closeted queer kid) because she idly experiments on him without fully informing him of what he’s getting into, but she’s special and this is how they discover she has the best angel powers of them all and that means that it gets brushed over. Jace and Clary are jealous and possessive jerks toward each other while also pushing each other away throughout City of Ashes and City of Glass, but this is portrayed as excused because They’re Doing It For (unhealthy, selfish, possessive) True Love.

The one that drives me furthest up the wall is the scene where Jace stalks into a bar, orders a Scotch (because Scotch is a Man’s Drink, never mind that the Man in question is a bratty 16-year-old), throws the Scotch at the wall because he’s Overcome By Emotion, shouts at the people in the bar, and then demands a replacement from the bartender. This whole sequence gets portrayed as “look how much Jace is suffering” but I couldn’t get away from thinking about how much the bartender, the random patrons, and everyone else who has to deal with his temper tantrum must be suffering. Seriously, that’s the kind of behavior that I would punish in a six-year-old, because I’d expect a six-year-old to know better, whether or not the six-year-old thinks that he’s in love with his sister and that their father is an evil demagogue (Luke Skywalker called and he wants his plot back, by the way) and whether or not the six-year-old has a Sad Hawk Backstory™.

Anywhoo, I find Clare’s work… frustrating. Obviously. I have ambivalent feelings about most of the other sci-fi/fantasy for which Animorphs has ruined me forever, but Clare’s work is high on my personal “nah” list.

Quick inevitable aside to How Animorphs Did It Better: the kids view avoiding violence as the ultimate end for which they are fighting this war. Any time the protagonists have to choose between a violent means and a nonviolent one, they struggle to find a nonviolent one. There are good yeerks (Aftran, Illim, Niss), bad andalites (Estrid, Alloran, Samilin), and even bad Animorphs (mostly David, but to a lesser extent Marco and Rachel). Even then, the good-bad dichotomy gets complicated and continuously questioned, such that the “good” guys do a lot of things that everyone can agree are “bad” and get condemned for it. Marco acts like a jerk toward Tobias early on in the series, and the fact that he’s doing it partially because he’s (reasonably) terrified of dying thanks to what Visser One did to both his parents and partially because he’s whistling in the dark very clearly doesn’t excuse his behavior. Visser One spends AN ENTIRE BOOK trying to argue that her bad behavior is the product of her having had a rough life, and at the end of it Applegate succeeds in getting us to hate her more, not less. Predominantly “good” characters do “bad” things (Ax killing Hessian soldiers, Cassie letting Tom’s yeerk have the morphing cube, Jake flushing the yeerk pool), just as predominantly “bad” characters do “good” things (Visser Three helping defeat the nartec and helmacrons, Visser One protecting Darwin and Madra, Chapman’s yeerk agreeing to help Melissa), and the series doesn’t offer a moral dichotomy any more absolute than “try not to harm people, I guess. Oh, and do your best to prevent other people from getting harmed, if they can’t protect themselves.” The series shows that Tobias’s sad human backstory doesn’t make it okay for him to annihilate the mercora or even to snap at Rachel when he’s hangry.

I just… really love Animorphs. And it ruined me for every single other book series on the planet.

#awaytothink#answers#asks#violence#morality#aggression#freudian excuse#jace wayland negativity#cassandra clare negativity#mortal instruments negativity#nothing to do with animorphs#albert bandura#body negativity#ya sf

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sincerely-Held Bigotry

Originally Published on June 26, 2017 on Eichy Says

It’s been exactly two years since the U.S. Supreme Court ruled – in the 5-4 decision of Obergefell v. Hodges – that same-sex marriages must be legal for secular purposes in all fifty states. This had been a long time coming...and this verdict (in favor of same-sex couples who desire legal marital protections) should have been rendered decades ago!

Two years later, there has been no erosion of rights for opposite-sex couples who wish to enter a civil marriage. Same-sex couples now have a significantly higher level of equality that they were denied for so long...although there are still battles to be fought on behalf of LGBT people in the areas of employment discrimination, adoption, and harassment.

The major “gay issue” of the moment appears to be the battle over whether “religious liberty” is a viable defense if private business owners want to discriminate against LGBT customers. This was precipitated by the case of Masterpiece Cakeshop, Ltd. v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission, where Colorado-based baker Jack Phillips refused to design a wedding cake for the same-sex nuptials of customers Charles Craig and David Mullins. It will now go to the U.S. Supreme Court to be dissected and analyzed at the federal level.

In November of 2015, I wrote an editorial entitled “Faking the Cake,” which described my socially-libertarian views on this controversy. My position on the “Wedding Cake Case” remains the same, today: I oppose the concept of federal employees being able to deny services to LGBT people in the public sphere (as Kim Davis infamously attempted to, that same year)...but I believe that *PRIVATE* business owners reserve the right to deny service to any citizen – for any reason – at their discretion. They just have to be prepared for the social and/or economic fallout...in the form of backlash or boycotts from the general public.

My narrative, today, goes more deeply to the core of why “anti-gay” attitudes are still an issue in the 21st Century. By and large, it’s for the same reason that we still see “whiteness,” “masculinity,” “attractiveness,” personal wealth, able-bodied (or able-minded) dynamism, and interpretations of what makes someone a “good Christian” revered by so many Joe Schmuckatellis throughout the United States.

When I attended the University of Wisconsin - Eau Claire in the early-aughts, I took a couple of courses from Bob Nowlan, a Professor of English, Critical Theory, and Cinema Studies. Bob is openly-gay and extremely revolutionary in his approach to teaching as well as when developing his curriculum emphases. In light of the fact that he himself is obviously pro-LGBT, he structures his course content in a way that acknowledges (and introduces students to) opposing viewpoints that can be hostile toward LGBT people (juxtaposed alongside the pro-LGBT perspectives, of course).

I once took an invigorating critical theory course taught by Bob that was entitled “Queer Theory and Culture.” During one class session, he showed us a video documenting the positions publicly taken by citizens who mobilize against ballot initiatives for LGBT equality (or, as it often happened to be the case, in favor of ballot initiatives that would enshrine secular discrimination against LGBT Americans into state constitutions).

In one segment of that video, I vividly remember a middle-aged Boston-area woman being interviewed (in her church, of course) about her opposition to the legal recognition of same-sex marriage. She insisted, casually and evenhandedly, that her opposition didn’t come from a place of hatred or spite...they were simply, in her words, “sincerely-held” religious beliefs.

During the group discussion that Bob led, afterward, I expressed my view that people such as this Boston woman are the real problem – as opposed to the “God Hates Fags” picketers who pop up at funerals or Pride Parades. It’s very easy for any of us to see the hatred oozing from the pores of the Westboro Baptist Church’s congregation. But when someone peddles their orientationism against LGBT people in such a cavalier, articulate, non-aggressive manner – as this Boston woman did – it normalizes and dignifies the “othering” of Americans who aren’t heterosexual. It makes it seem as though heterosexism or homophobia “aren’t quite as bad” when coming from someone who appears halfway-sane.

The semantic choice of someone’s bigoted worldview as being “sincerely-held” is deceptive. In my September 2016 op-ed entitled “Purple Pain: A Fairy Tale of ‘False Moderates’,” I point to former U.S. Senator (and Al Gore’s 2000 vice-presidential running mate) Joe Lieberman as a classic example of someone who spouted the mantra that disapproval of homosexuality isn’t coming from a place of hatred or discrimination...but rather, is based on “sincerely-held morally-based views.”

And look no further than the ambivalence of my former sociology instructor, Leonard, when we tackled homosexuality during our classroom discussions.

At the root of it is the misperception that homosexuality and bisexuality are all about gluttony, superficiality, and deviance. However, this flavor of cultural orientationism doesn’t exactly gel with secular parity in the legal sense.

First, there’s the misnomer that “If everybody on the planet was gay, humanity would become extinct as a species.” What they fail to acknowledge is that, if everybody on the planet was exclusively heterosexual, there would be even more global overpopulation than there already is.

And, if a lack of procreation is the basis for denying people legal equality, then, by that same reasoning, infertile people shouldn’t be allowed to remain married. Or, couples who choose not to raise children shouldn’t be allowed to remain married.

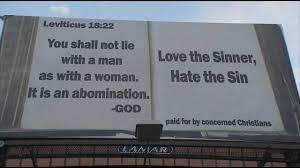

Then there are the classic Bible verses that people trot out, which appear to condemn homosexuality: namely Romans 1:26-27 and Leviticus 18:22.

What biblical-loyalists fail to acknowledge here is that the meaning of Scripture was much different back then compared to nowadays. We disregard biblical text that makes reference to marital obedience, slavery, divorce, and eating shrimp...yet, we, for some reason, are still willing to cling to the passages that cite homosexuality as a sin.

This, of course, assumes that the Bible was 100% unaltered between the present and when Scripture was first written. And, even if the Bible remained 100% intact over centuries, you still have to have faith to embrace the implication that all of the Bible’s multiple authors were writing strictly based on divine intervention...rather than interweaving their own deception, ignorance, or schizophrenia into biblical text.

If you believe that, then you are CHOOSING to believe that. Which means...you are CHOOSING to be bigoted. Which means...on some level, your embrace of this bigotry is either conscious or subconscious. Which means...you will get called out on it. #SorryNotSorry

There is also the red herring of bringing pedophilia, necrophilia, and bestiality into the equation. “Oh, if we accept homosexuality, should we then proceed to accept pedophilia, necrophilia, and bestiality?”

The big difference: homosexual relationships can (and should) involve consent. If you sexually prey upon a child, the child can’t legally consent. If you try to have sex with a corpse, that dead person cannot consent. If you wish to have sex with an animal, the non-human creature cannot legally consent.

Additionally, moral invokers of the “slippery slope” fallacy will bring up the scenario of the American public hypothetically condoning incest. But a romantic/sexual relationship between two people of the same-sex related by blood is NOT incest. Because they’re, you know, NOT RELATED BY BLOOD.

As far as polygamy and polyandry (multiple-spouse relationships)...I wouldn’t personally desire that for myself. But if several parties want to legally enter into a group marriage – and all of those parties are in consent – I wouldn’t have any problem with that.

Finally, even if there’s One Supreme Deity who has indeed determined that homosexuality is a sin, unconditionally – what gives us the right to use the law to legislate that morality? If homosexuality is so morally-abominable, wouldn’t He just punish all of us queers upon our deaths, anyway?

There are many things that could be construed as “sins,” which we routinely overlook (or, at least, we don’t retool the law to hold people hostage).

Should all secular opposite-sex marriages (if there is no house-of-worship involved) be dissolved, and then be replaced with state-sanctioned covenant marriages?

Should every married couple have to gain the permission of a clergyperson before legally getting a divorce?

Should any case of proven infidelity committed by a married person also come with automatic punitive penalties under the law?

Should heterosexuals who enter non-romantic marriages-of-convenience be sentenced to prison time for violating “the intent of God”...???

In most cases, what I believe it really comes down to is that the folks who rail against homosexuality, deep down, view it as “icky.” So they will try to rape and maul the law itself as a way of enforcing their “sincerely-held beliefs” upon everybody else.

Well, I find it “icky” when people litter inside of grocery stores. That doesn’t mean I’m going to call for all grocers to install 1984-style cameras and draconian behavioral guidelines in their supermarkets.

But, as William Shakespeare wrote, “The lady doth protest too much, methinks.”

Translation: conservative activists who crusade against secular recognition for same-sex couples want the “upper hand” in persuading others to similarly subscribe to the bigoted beliefs in which they themselves are choosing to believe. They will use buzz phrases like “lifestyle choice” or “special rights” to enact this agenda.

Why else would we see states such as Mississippi tout bigoted legislation? – such as House Bill 1523 (the Protecting Freedom of Conscience from Government Discrimination Act), that codifies discrimination by purposely using the phrase “sincerely-held religious belief” to justify equal protection of LGBT citizens.

Some of the language from the actual bill:

“...sincerely held religious beliefs or moral convictions...”

“...marriage is or should be recognized as the union of one man and one woman...”

“...sexual relations are properly reserved to such a marriage...”

“...male (man) or female (woman) refer to an individual’s immutable biological sex as objectively determined by anatomy and genetics at time of birth...”

This is why critics accuse conservatives and/or Republicans (or even some conservative Democrats) of trying to intrude into people’s bedrooms.

And, this is why current Vice-President Mike Pence will not win – assuming that Trump must step down, and Pence runs for the presidency in 2020. We never asked for Mike Pence (we never even asked for Trump, and we certainly didn’t ask for Trump to pick Pence as a running mate)...and, in the process, Pence would take down the entire conservative movement along with himself.

Job discrimination, policing bathrooms, Pride Flag shaming, heteronormativity, and “religious liberty” laws (or corresponding attitudes). Bring it on, bigots! We survived the Holocaust, McCarthyism, the Stonewall Riots, the AIDS panic, and attempts to enact the Federal Marriage Amendment.

This time around, social media and generational awakenings – as well as common sense – are on our side.

Are things better now – for gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender people – than they were five years ago? Absolutely – the secular legalization of same-sex marriage has made all the difference. We’re not going back. Just think how good things could be five years FROM NOW.

So no, I don’t believe the government should force private businesses to provide services to same-sex couples or for gay-friendly content. Just like I don’t believe the government should force churches or other religious establishments to recognize same-sex marriages.

On the other hand, you may whine that we’re trying to force you how to think. That’s not quite true – we’re asking you to reevaluate how you think, insofar as one very specific topic (homosexuality).

Condemning someone else based on their sexual orientation per se is no different than if you were to condemn someone solely based on their genitalia, their genetic ethnicity, their gender identity, their peacefully-practiced religion, their physiological or neurological disability, the geographic region in which they reside, or the income bracket that they happened to be born into.

And that’s my “sincerely-held common sense” talking!

0 notes

Text

“All the better to see you with…”- An Analysis of “The Company of Wolves”

July 2008

In his 1984 film adaptation of Angela Carter’s short story “The Company of Wolves” Neil Jordan paints the archetypal landscape of Western folklore upon the subconscious of the film’s protagonist, a young girl named Rosaleen. Sweating beneath the red lipstick and blush painted on her face, Rosaleen tosses in her bed one afternoon as a nap becomes a nightmarish tale. Her nightmare occurs in a kitschy mockery of a medieval world, a cobwebby forest village like an antiquated set invoking fairy tale imagery; emblems, like gingerbread cookies, toads, apples, serpents and dove-splattered wells, appear throughout the film. Rosaleen stands in for the well-known Little Red Riding Hood with her red cloak, wise granny and wide-eyed fear of wolves.

Jordan’s allusion to the classic fairy tale toys with various versions of the wolf and introduces a complex female protagonist who destroys the story’s optative certainty by ultimately becoming a wolf herself. The Company of Wolves becomes a garbled manipulation of archetypes—hero, beast, bride, mother, witch—reflective of the collective unconscious that informs the “real” Rosaleen in her subjective experience as a pubescent girl. Marina Warner explains that Carter’s writing reveals “the imagination’s own capacity for protean metamorphosis, which allows it to leap barriers of difference, or at least play with them till they seem to totter and fall” (Granny Bonnets 194). It is this “mercurial slipperiness of identity” (Warner, Granny Bonnets 194) that Rosaleen explores in her nightmare, confronting gender, specifically, and its role in her identity formation. In The Company of Wolves Jordan tampers with various archetypes to convey that, no matter what she does, Rosaleen will be punished for being a woman—either preyed upon, blamed or confined—and must therefore disavow her femaleness; in so doing, however, she inevitably accepts the patriarchal codes that determine the limited ways in which one can be female and thus betrays herself.

The first archetype Jordan recreates in his film is that of the big, bad wolf. In its classic form, the wolf “represents male predatoriness” (Hourihan 198). As with the original fairy tale, Carter’s story warns its readers: “If you stray from the path for one instant, the wolves will eat you” (111). In other words, this wolf symbolizes the unrepressed, savage, sexual urges of men (Warner, Beautiful Beasts 52) that little girls are taught to understand and fear. Though not visible in Jordan’s film, Carter tells us that the predator’s “genitals are a wolf’s” (113), illustrating the rapist implications of this archetype. The film’s primary werewolf, the “huntsman”, embodies it in some ways. With his trusty needle pointed north, he takes Rosaleen’s basket and mirror and replaces them with his hat, like a seal of ownership in exchange for her maidenhood. In a dramatic—and therefore pivotal—shot, the huntsman tells Rosaleen that he desires “a kiss,” proclaiming the wolf’s predatory intent; when Granny later asks what he has done with her granddaughter, the huntsman replies, “Nothing she didn’t want.” Thus, the wolf here represents the inescapability of male sexual predation.

The omnipresence of wolves in The Company of Wolves effectively symbolizes the pervasive sense of danger in Rosaleen’s world and subconscious. Indeed her caregivers naturalize the notion; her father speaks of “losing” his daughter to a boy, suggesting that she is property for the taking, and her granny unquestioningly interprets a young boy’s actions in a childish game as sexual assault. Her mother preaches that they “won’t live quiet” until “the beast is dead.” Older and presumably wiser characters convey these attitudes with conviction, and the many wolves of Rosaleen’s nightmare reveal her growing awareness of perpetually-lurking predators threatening her safety.

Complicating the stock character of the big, bad wolf, both Jordan and Carter occasionally construct the wolves of their stories as tragic; evading the stigma of pure evil attached to the predator, here the beasts become victims. In “The Company of Wolves” Carter describes the wolves’ sadness and how they cry “as if the beasts would love to be less beastly if only they knew how” (112). At times, her narrator tells, “the beast will look as if he half welcomes the knife that despatches him” (112). Jordan’s climactic scene between Rosaleen and the werewolf includes a dramatic shift when the supposed victim calls the beasts “poor creatures.” The wolves of The Company of Wolves thus invoke sympathy as well as fear.

In her chapter “Beautiful Beasts: The Call of the Wild,” Warner argues that this newfound softness for the predator reflects a shift in the values that we as a society accord nature and humanity (63). She explains that whereas nature once symbolized the savage and the evil (58), today it ironically becomes a sinless sanctuary (51) with its wild inhabitants as “healing figure[s]” (55) appeasing the “threat of entropy in nature, brought about by human achievements” (55). Coinciding with this increasing wariness of modern civilization, Warner notes, Perrault’s “Little Red Riding Hood” casts the wolf not as wild beast but as the embodiment of the “deceptions of the city and the men who wield authority in it” (Granny Bonnets 183). Employing the legend of King Kong as example, Warner argues that beast becomes victim when woman is enemy for stunting his libido and domesticating him (Beautiful Beasts 61). The beast then represents the “true” male repressed in a modern consumer culture—another feminized scapegoat—hence the contemporary ambivalence toward the beast evident in The Company of Wolves.

Jordan’s film explores this contemporary disdain for consumer culture, constructed as feminine, through the misogynistic story of the witch. In a suddenly Victorian setting, powdered men and women in wigs and elaborate costumes feast on a lavish wedding meal in a pink banquet tent. Comically made-up and overindulgent, the drunken aristocrats consume their meal in a grotesque manner, conveyed by the absurdist style of the scene. When the witch surveys the event and turns its members into wolves, circus music accompanies the equally grotesque, absurd and comical transformation yielding wolves in pretty, pink dresses. The farcical scene represents the “feminine” aspects of consumer culture in a most unflattering light; silly, frilly and maddening, the grotesquely ornate Victorians stand for that which has stopped the beast in his tracks. Because Rosaleen dreams that this tent sits before her “real” house, the viewer sees that she somehow belongs to this feminine world, or, at least, has played at it like a game removed from whatever her reality may be.

It follows then that Jordan’s wolf occasionally becomes “poor creature,” or what Warner calls “a figure of man, a desiring, aspiring, frustrated, tragic male” (Beautiful Beasts 61) in the face of domesticating, frivolous women. Rosaleen asks the werewolf, “Are you our kind or their kind?” His pathetic response—“My home is nowhere,”—posits him as an abject Other to be pitied in his beastliness. Against a romantic score, Rosaleen calls the werewolf a “gentleman” and succumbs to sympathy for her predator. As Beauty chooses the Beast, so Rosaleen may desire the wolf sexually, if only for a moment (Jordan visually conveys Carter’s sensual imagery as the werewolf strips: his “vellum” [116] skin, his “ripe and dark” [116] nipples). Ultimately, she tames the werewolf, turning him into a whimpering puppy to take under her wing. As Margery Hourihan explains in her discussion of archetypes, all females eventually serve as mothers in the fairy tale (166). Jordan’s climactic scene thus reflects the ambivalent terrain of the wolf archetype that allows the predator pleas for understanding.

Jordan further examines this ambivalence through the boy who becomes a werewolf. Perhaps a short tale of male puberty, this scene depicts a hairless, forest-dwelling boy who encounters a fancy car driven by a sly Rosaleen. Accepting and applying an ointment from a man inside the car, the boy suddenly grows hair and screams in horror as the forest swallows him whole. The “real” Rosaleen wakes to find this image in her bedroom mirror, as though she feels responsibility for this attack of the “voracious vagina” (Hourihan 191). As products of Rosaleen’s subconscious, these characters demonstrate her internalization of the knowledge that patriarchal society loathes femininity. Furthermore, because she places herself in the Little Red Riding Hood role, the viewer sees that she has begun associating herself with the elusive concept.

More concretely, The Company of Wolves explores female archetypes that Rosaleen might embody. Firstly, Rosaleen consistently represents the “barely pubescent” (Hourihan 196) virginal bride. In Carter’s words:

Her breasts have just begun to swell; her hair is like lint, so fair it hardly makes a shadow on her pale forehead; her cheeks are an emblematic scarlet and white and she has just started her woman’s bleeding, the clock inside her that will strike, henceforward, once a month. (113)

In his film, Jordan places Rosaleen’s menses, and what we are to therefore understand as her coming-of-age, at the centre of the story. The entire film is her nightmare and in it she assumes the role of a naïve girl at the cusp of her “sexualization.” She innocently questions female passivity when her granny laments her sister’s death, asking, “Why couldn’t she save herself?” Granny scoffs at Rosaleen’s ignorance, telling her that she is but a child; in other words, girls in this society will grow to learn of their place. When Rosaleen proudly states, “I’d never let a man strike me,” Granny, again, “knowingly” explains that men are “nice as pie until they’ve had their way with you, but once the bloom is gone, oh, the beast comes out.” Granny and others around her naturalize the idea that, shortly, Rosaleen will make a good, virgin bride.

Hourihan argues that the bride archetype serves the ubiquitous hero as his subordinate (196) and ultimately teaches girls that “all will be well when the prince appears” (198). Passive, submissive and void of agency, brides then serve the aforementioned predator as mere prey. Jordan illustrates this archetypal relationship through the tale of the newlyweds. Here the virginal ingénue in white soon learns that hiding beneath the hairless skin of men lurks a beast poised to attack her as a bride, a mother or a whore. Her first husband tears off his skin to reveal a werewolf, while her second simply beats her for no apparent reason. This scene thus conveys the idea that women should meet men’s needs but remain peripheral lest they overstep their boundaries.

Slowly internalizing the role of virgin bride, Rosaleen experiences her coming-of-age as shame and self-objectification. Jordan employs recurring images of contamination to highlight the dirtiness that Rosaleen feels for menstruating: spiders on her bible, mice in her dollhouse and maggots in her apple. Here, rodents infest symbols of chastity and childhood. The motif of red blood staining things draws a further parallel between Rosaleen and dirty animals with contamination to be ashamed of.

As Rosaleen’s shame grows, so does her awareness of herself as a sexual object. The character of the gangly, sniveling “amorous boy” exemplifies the absurdity of male privilege, that a boy like him can pursue the fair Rosaleen and make her feel watched, objectified and consequently aware of her burgeoning “sexuality” before she even understands it on her own terms. Although Rosaleen still mostly rejects the boy, her ambivalent coyness when dealing with him reveals that she has already begun rehearsing this female role; indeed, she goes on to employ it with the werewolf. Jordan thus creates a girl’s nightmare rife with anxiety about “becoming a woman” as seen through the eyes of others—namely, men.

The second female archetype Jordan examines in The Company of Wolves is that of the mother, who, for Hourihan, represents the inevitable fate of all women in the hero’s realm (166). Mothers in Western folklore serve to nurture the male hero through an oedipal bond (Hourihan 159). Fittingly, fairy tales commonly feature fatherless boys and motherless girls. Hourihan thus concludes that “the relationship most crucial to disrupt and destroy in patriarchy is that between mother and daughter” (202), as this relationship harbors the most potential for female solidarity. In The Company of Wolves, Rosaleen fares better than the archetypal maiden: not only is her mother alive, but the two communicate, enjoy one another’s company, and it is her mother’s instinct that saves her from getting shot by her own father following her transition to she-wolf.

However, these maternal strides may only mirror our contemporary patriarchy in which women enjoy a modest increase in female solidarity. While Rosaleen’s mother loves and supports her daughter, she also models for her the picture of ideal motherhood: confined to the private sphere in submission to the beast’s domination, as it were. As if to justify her position, she tells her daughter that, “if there’s a beast in men, it meets its match in women, too.” Seemingly content in the private sphere, Rosaleen’s mother guides the viewer through Rosaleen’s domain. Notably, The Company of Wolves takes place either in the domestic space or in the wild, but never in the public sphere. As Hourihan explains, the home, for the hero, is the space between public culture and the chaos of nature (199). Upholding this private space, Rosaleen’s mother states, “Thank god we’re safe indoors.”

Ultimately, she teaches Rosaleen to expect the same fate. Rosaleen also discovers this independently when, clamoring up a tree, seemingly in an act of freedom, she finds herself more like a kitten trapped in a dead end. Atop the tree she finds a mirror, red lipstick and babies hatching from eggs in a nest. As with the witch rocking her baby’s cradle on a treetop, this image symbolizes the final marker of appropriate femininity and the inevitable destiny of the virgin bride: motherhood.