#macedonian history

Text

“Alexander the Great had three sisters - Cynnane, Cleopatra, and Thessalonice - and all three were eventually murdered. Since both' of Alexander's sons met similarly violent ends, it may appear at first glance that little distinguishes the pathetic life and death of each of these three royal sisters from the more pathetic and yet shorter lives of their nephews. Indeed, even earlier in the century, before the long and troubled demise of the Argead house had begun, very few male Argeads managed to die at home in bed.

On reflection, however, the very fact that a long dynasty was coming to an end should have meant that the sisters of the last king would have a better chance of survival than the minor male heirs of that king. After all, once the father is dead, the heirs are for practical purposes (assuming they are well below the age of maturity) no man's sons, and can do no would-be dynast any more than short-term good, whereas the king's sisters can be married and thus legitimize the seizure of royal or quasi-royal power. Better yet, a king's sister may produce children of the blood of the old royal house, as well as the new.

But two of Alexander's sisters did not realize the potential advantage seemingly inherent in their situation and ultimately all three died exactly because they were Philip II's daughters and Alexander's sisters. This failure to realize the potential to be the bridge between two dynasties is most surprising in the case of Alexander's full sister, Cleopatra. Analysis of the careers of Alexander's relatively obscure sisters, worthwhile as an end, in itself, should answer the question of why the Successors proved to prefer murder to marriage (in two of the cases) as well as produce important information about the nature of Macedonian monarchy in a period of great and rapid change. The significance of the similarity in ultimate fate of the three sisters and their nephews has been ignored for too long.

“... Calling Alexander's sisters his "relicts" is meant to convey two truths about them: their similarity to the other relics of Alexander (his corpse, his tent, and, of course, his empire) and their manipulation by various of the Successors and (by means of allusion to the older meaning of "relict" as a female survivor of some related and now departed male, with its implication of the lack of a separate existence for such women) their peculiarly property-like quality in the period after the death of Alexander. The answer to the question posed initially - why did Alexander's sisters fare so poorly and so similarly to their nephews - should now be clear. Alexander had no successor. Even Antigonus, although interested in the same land area as Alexander, was not a true successor to the curious monarchy Alexander had invented - a traditional national monarchy onto which a curious sort of personal monarchy had been grafted - Antigonus was, like the other generals, on the way to creating a personal monarchy. Thus even he did not really need Cleopatra. Cassander, with his marriage to Thessalonice and at least superficial attempt to imitate the traditions of Macedonian monarchy, could not really be Philip's heir because he could not be an Argead; he had murdered Argeads and would probably have liked to murder more. Until the death of Alexander, Macedonian kingship had been tied to one dynasty. This was so much the case that the kings used no title, but simply signed themselves as so and so, son of an Argead. Trying to decide whether Philip's or Alexander's reputation was greater after 323 is ultimately devoid of any real political meaning; neither had any real successors and thus Alexander's sisters and Philip's daughters, representing as they necessarily did continuity with what had come before, could have no future.

Cynnane died in an ill-advised attempt to take royal power by military and quasi-military means; the army did not save her. Thessalonice died in the death throes of the pseudo-dynasty Cassander had fabricated, her death demonstrating that even her son did not need to see himself as the heir to the Argeads. Cleopatra died making one last attempt to function as a symbol of continuity, and for that she was murdered. The sisters were expendable because continuity was neither needed nor genuinely desired.”

Elizabeth Carney, “The Sisters of Alexander the Great: Royal Relicts”

*I disagree that Cynnane's attempt to take royal power was ill-advised. As Carney herself points out in another book, "although this daring plan ultimately proved fatal for Cynnane, it succeeded in its object and was brilliantly conceived".

#the visceral tragedy of thessalonike's life always gets me#historicwomendaily#history#cynnane#cleopatra of macedon#thessalonike#thessalonike of macedon#alexander the great#macedonian history#ancient greece#ancient history#queue

28 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi Jeanne I'm Elena of @alessandroiiidimacedonia

I'd like to know if there is a term that indicates all the literary production about Alexander the Great, of any genre fiction and non-fiction, poetry or not, which see it positively and also negatively, by ancient and modern authors, contemporaries and later.

Thank you,

Elena

Hi, Elena!

Ernst Badian dubbed us "Macedoniasts" some decades ago, ha.

I like that term, as it's inclusive of the study not just of ATG, but also of Philip, the kings before them, the Macedonian people and culture, and also of the Hellenistic era that followed.

So we (professional, semi-professional, or amateur) are all Macedoniasts.

Welcome to the club. ;)

#Alexander the Great#Macedonian history#Philip II of Macedon#ancient Macedonia#ancient Greece#asks#Ernst Badian

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

the assassination of Philip of Macedon (336 BC)

Philip II of Macedon ruled over Macedonia from 359BC until his assassination in 336BC. He was killed by his bodyguard, Pausanias of Orestis, during the festivities for the marriage of Alexander I of Epirus and Cleopatra of Macedon (Philip's daughter).

Philip was entering the theatre of Aegae (capital of the Macedonians) unprotected, in order to seem more approachable and conspicuous. He was then approached by Pausanias and stabbed in the ribs with a dagger. The assassin immediately fled and ran towards the city gates, where his associates were waiting with horses for his getaway. However, Pausanias tripped on a vine root and was quickly overpowered by his fellow bodyguards, who stabbed him to death.

(1880 illustration depicting the assassination)

the motive

According to Greek historian Diodorus of Sicily in his World History, Pausanias of Orestis verbally abused his rival for the king's affections, a man also named Pausanias. The second Pausanias was unable to tolerate the insult and decided to prove himself by positioning himself in front of the king during battle, subsequently dying from the blows he protected Philip from.

Philip's uncle, Attalus, wanted to punish Pausanias for causing the death of his friend (the other Pausanias). He invited him to dinner, got him drunk, and allowed his stablemen to rape Pausanias. Philip, however, did not punish Attalus, possibly due to their kinship and the fact that Philip needed Attalus (he commanded Philip's forces). While Philip attempted to compensate by promoting Pausanias, he remained resentful and wanted to exact revenge on the king, who had denied him justice.

Despite this explanation, suspicions still fell on Philip's wife Olympias and his son Alexander the Great, as they had a lot to gain from Philip's death. In the epitome of Pompeius Trogus' Philippic Histories, Latin writer Justin suggests that Pausanias was instigated to commit the act by Olympias, and that Alexander was not unaware of his father's impending death.

(18th century piece depicting Olympias and bust of Alexander the Great, circa 330BC)

part 1/25 of a series introducing the assassinations outlined in Francis John's 1903 book, Famous Assassinations of History from Philip of Macedon, 336 B.C., to Alexander of Servia, A.D. 1903

#history#philip of macedon#alexander the great#macedonian history#ancient history#macedonia#q#historical assassinations series#ancient macedon#classics#long post#.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Alexander covering the body of Darius with his cloak

by Charles Meynier

#alexander the great#darius#art#charles meynier#antiquity#history#europe#european#asia#persia#persian#ancient greek#ancient greece#macedonian#macedonia#greek#greece#achaemenid empire#macedonian empire#king#persian empire

190 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alexander: I will crush every kingdom in India and kill the kings, and most importantly kiss Porus.

Hephaestion: Hmm..?

Alexander: KILL PORUS-

#macedonian sillys#greek history#ancient greek history#indian history#ancient indian history#ancient greece#ancient india#alexander of macedon#alexander the great#porus#hephaestion

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

#I’m fine I’m fine I’m normal I’m fine#dark academia#alexander the great#hephaestion#alexander x hephaestion#ancient greece#academia#history#girls when#dark academia aesthetic#macedonian#ancient greek history#happy ides of march I only care about alexander#but also girls when brutus#girls when et tu brute#brutus#rome#ides of march

316 notes

·

View notes

Text

Getting some work done on the Macedonians, going fast and dirty with them for a fun "break" from more intense projects

Works been rough and my car is having a time so a nice repetitive calming exercise like this is nice

#art#canopiancatboyart#painting#miniature#hail caesar#macedonian phalanx#macedonia#alexander of macedon#ancient greece#ancient history#tabletop#miniatures#wargaming#3d printing#board games#miniature painting#greece

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

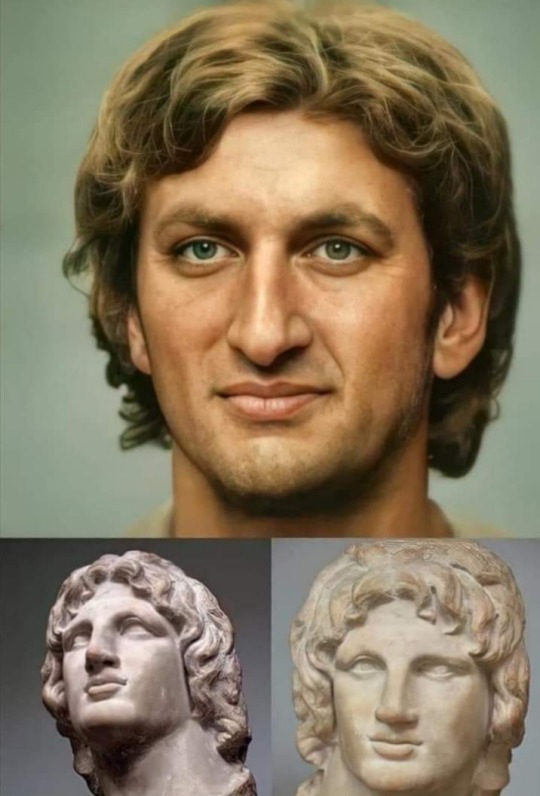

Recreating facial features of "Alexander the Macedonian" using the digital system according to the shape of his face in carved statues.

Alexander the Great died in the palace of King Nebuchadnezzar in Babylon in Iraq in 323 BC, when he was only 32 years old.

—

Alexander III of Macedon (20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon.

He succeeded his father Philip II to the throne in 336 BC at the age of 20.

He spent most of his ruling years conducting a lengthy military campaign throughout Western Asia and Egypt.

By the age of 30, he had created one of the largest empires in history, stretching from Greece to northwestern India.

He was undefeated in battle. He is widely considered to be one of history's greatest and most successful military commanders.

#Alexander the Great#Alexander III of Macedon#Alexander the Macedonian#Archaeo Histories#Macedon#Ancient Greece#Ancient Empires

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

People are like 'our peasant ancestors lived better than we did with fewer working hours and adored weather'

The same people who think pressing a screen on a smart phone is true slavery, and that there was ever a point in life where simply getting food and clothing wasn't great toil with long hours for relatively simple rewards in that 90% of human existence before recorded history and the 5% that's been recorded. They would go feral if asked to live a true peasant's lifestyle without any electronic conveniences, subject to the whim of nature and of the seasons that cannot be controlled, asked to feed and clothe themselves the way most of humanity did for most of its history.

Farming isn't idyllic now, in the 21st Century, with machines and knowledge a smelly lousy peasant didn't have and didn't know how to have. In the days when the cutting edge technology was the ass end of a mule or an ox and where you had to do all that weeding stooping over in a hot sun for the entirety of the working day it was much worse. There's a reason the Bible calls farming a curse!

Our ancestors would weep with joy that their modern descendants live in lives less brutal and horrifying than what they would have taken for granted, if anything. Nostalgia is a liar, at best, and it is seldom at its best.

#lightdancer comments on history#look I have a literal graduate degree in history#and one of the biggest things I've learned from that is I like reading and writing history#i would not want to live in the past#and that's merely focusing on the reality of my disability let alone being queer when in the past one or both would well....#history is only fun for some people in relatively narrow intervals#and most people who delude themselves they'd be Alexander the Great would be the person scooping Bucephalus's shit#or more likely just shanked in the gut by a random Macedonian soldier who didn't even register it

207 notes

·

View notes

Text

The elite bodyguard of Alexander the Great is said to have killed a lion with his bare hands and this is how he gained Alexander’s attention. This man was Lysimachus and he eventually had a small empire of his own.

#Lysimachus#Macedonian#Macedon#Macedonia#Alexander the Great#general#Greek#elite bodyguard#The Battle of Hydaspes#thrace#Wars of the Diadochi#Ptolemy I#Cassander#Seleucus#Antigonus#Diadochi#ancient#history#ancient origins

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

Such a loving family...

#greek philosophy#philosophy#socrates#Plato#Aristole#alexander the great#history#alexander of macedon#Macedonian empire#Greece history#greece#family#loving family#student

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

“...Ancient authors, while generally hostile to Olympias, are not uniformly so. Plutarch, for instance, although he provides an extremely negative picture of Olympias in his life of Alexander (e.g., 2.9, 9.5, 10.1, 4, 68.5), offers a different and much more positive picture of her in the Moralia (141b-c, 243d, 799e). Even Justin, notorious for his implausible account of Olympias' supposed outrageous behavior after the death of Philip (9.7.10-14), gives Olympias a long and heroic death scene (14.6.6- 13). Diodorus, although generally critical of Olympias, also grants her a noble death (19.51.5). Indeed, female bravery, especially in the face of death, and often characterized as man-like, is admired by many ancient authors.

Whereas the current historiographical trend in scholarship about the reign of Alexander disdains biography and resists speculation about the motivation of the great conqueror, most of those who deal with Olympias confidently assign motives to her actions, motives which are usually negative and almost always personal rather than political. The ancient sources, biased or not, are not always the basis for this assignment of motivation. Indeed, unpleasant motivation attributed to Olympias, while similar in ancient sources and modern scholarship, is not identical. Ancient sources tend to depict Olympias as motivated primarily by her difficult personality (they often imply that she liked to make trouble for trouble's sake) and by her natural nastiness, whereas modern scholarship tends to stress vengeance and something very close to madness, despite the fact that no ancient source characterizes Olympias' actions as mad and that very little stress is put on vengeance as her motivation. The actions of male contemporaries of Olympias, however brutal, are narrated in neutral fashion and their motivation is not usually perused, although apparently it is assumed to be rational if ruthless, whereas the actions of Olympias are described with a host of negative adjectives and adverbs and are assumed (although rarely argued) to be emotionally motivated.

Moreover, perhaps because of this unwarranted confidence in ascribing motivation to Olympias, modern scholarship sometimes supplements the already subjective judgments of antiquity. Scenarios and assumptions about Olympias have emerged that have little or no foundation in the ancient evidence. Many, for instance, assume that Olympias and her daughter Cleopatra did not get on and base their explanations for various political events on that assumption, yet no ancient source offers a shred of proof for this assumption. In fact, several sources describe mother and daughter as acting in concert for shared political goals and several more imply further concerted action. Similarly, many modern authorities assert that Olympias was universally unpopular in Macedonia after she brought about the deaths of Philip Arrhidaeus and his wife Adea Eurydice, whereas the narratives of Diodorus and Justin provide a more complex and nuanced picture in which Olympias emerges as a controversial figure, loathed by some and loyally supported by others.

This unfortunate state of scholarly affairs has had several consequences, none of them good. If we assume that scholars owe their subjects, groups or individuals, mass phenomena or personalities, some sort of fairness and balanced judgment, then clearly Olympias has not received it. Moreover, because of our unbalanced reading of this particular historical figure, our interpretation of Macedonian political events has been distorted. Distortion is especially a problem with the treatment of the period after the death of Alexander, and with the analysis of the reasons for the collapse of the dynasty which had ruled Macedonia from its historical beginnings. Problems with the treatment of Olympias' career have also affected our understanding of the most central of Macedonian institutions, the monarchy, and particularly the relationship of female members of the royal family to that institution.

Those who have recognized the hostile treatment of Olympias in the sources have attributed it, following Tarn, to propaganda created by Cassander to justify his elimination of her. While Cassander's efforts did doubtless play a part in the attitude of some of the surviving sources, it would be wrong to assume that he was the sole source of the hostility against Olympias.

The image of Olympias created by our sources results from the accumulation of many layers of prejudice. Greek unease with monarchy came partly from the role women played in succession politics; that Macedonian monarchy was polygamous only made for greater unease. A well-known but often carelessly read passage in Plutarch (Alex. 9.5) makes clear Greek distrust of Macedonian court politics: "The troubles in Philip's household produced many grounds for quarrels and differences because his marriages and love-affairs contaminated the basileia [kingdom or perhaps monarchy] with the customs of the women's quarters." (He follows this remark with an attack on Olympias' ill-nature to which we shall shortly turn.) It is a classic statement of Greek views about women and men and the association of the former with private life and the latter with public life: any mixing of the two worlds will lead to trouble. Hornblower has suggested that the emergence of Macedon as a great power and the consequent appearance for the first time of women like Olympias with political power in the Hellenic as opposed to the non-Hellenic world presented Greek historians with the problem of dealing with a new phenomenon, one they could not ignore.

Naturally, most Greeks disliked the role royal women played in Macedonian public life. In Athens, respectable women were, if possible, not even named in public, yet Athenian politicians refer to Olympias by name in the assembly, without even a patronymic (Hyp. Eux. 25; Aeschines 3.233). Shopping trips done for her sake (Aeschines 3.233) and acts of piety she performed (Hyp. Eux. 19) became matters of public discussion. She had a long public relationship with the Athenian assembly (Diod. 17.108.7, 18.65.1-7; Hyp. Eux. 25). Alexander sometimes liked to play the civilized Greek who did not indulge in backward Macedonian ways (e.g., Plut. Alex. 51.2). This pose may help to explain anecdotes about him and Olympias in which he takes the role of the conventional Greek male, reproving her for inappropriate behavior, and in one case implying that her actions were more typical of Epirus than Macedon (Plut. Alex. 39.12, 68.5; Diod. 18.49.4). All anecdotal material about the early life of Alexander should be treated with great distrust, but, true or not, if these anecdotes were actually generated by Alexander himself, they should be viewed in the context of his desire to be seen as Greek.

Much hostility is specific to Olympias herself: she is treated in a way that neither her daughter nor her rivals are. Some of this difference arises from the sources saying so much more about Olympias than about the others. Her career spanned three reigns and as the mother of Alexander the Great, she became a character in the vast body of anecdote his exploits generated. One wonders whether a lengthy Greek treatment of Cynnane, for instance, might not have demonstrated hostility to her aggressive militarism.

Clearly, though, some of the hostility of the sources to Olympias results from factors more essential than length or breadth of coverage. The sources object to her personality, as they interpret it. Consider the rest of the Plutarch passage just discussed: "the extremely difficult nature of Olympias, a jealous and indignant woman, exaggerated these difficulties because she provoked her son." Numerous anecdotes survive that have made her difficultness proverbial. Alexander jokes that she exacts a high price for his ten-month stay (Arr. 7.12.4). Her quarrels with Hephaestion and with Antipater remain vague, but the idea seems to be that she demonstrates her "difficultness” by involving herself in public affairs, often by unsuccessfully attempting to influence her son.

Since so many scholars have accepted the view of Olympias presented in these stories about her quarrels, it is important to note something at once simple and yet usually ignored: these stories do have a point of view and it is not that of citizens of governments with universal suffrage. The sources assume first that Olympias should not be active in public matters and therefore characterize such activity as interference. In fact we do not know that she was not acting within her role as king's mother; Hammond has suggested that she had a formal constitutional role during Alexander's reign. Even if we reject that suggestion, we might still conclude that her activity was well within Macedonian political patterns, how- ever much Antipater may not have liked it. They assume further that a woman who acts in such a fashion is difficult (xakeni), yet the great majority of modern scholars are unlikely to share such an assumption. Moreover, few scholars waste time wondering whether Alexander or Antipater or Attalus was "difficult"; we take it for granted that they were, that competitiveness and assertiveness were norms in the Macedonian court. Without realizing it, we have simply mirrored the cultural judgments of our source.”

A glance at the etymology of the word "virago" in Latin as well as in English will make my point clearer. In both languages, a virago is a person whose actions conform to cultural expectations of males ... So Olympias is a genuine virago, a woman who violated every expectation the Greeks had about women, but the antipathy her unconventionality inspired in the Greek world is a cultural assessment, not an eternal truth. Since all the surviving sources for the reign of Alexander date from Roman times and two of them were written in Latin, we should remember that Roman dislike of political women was also intense.

Not all the problems with hostility toward Olympias lie in the sources, nor does the nature of the sources explain why they have so frequently been read uncritically. We must recognize the fact that the image of the virago remains an extremely potent one in our own culture and it is very hard to give up a figure we so love to hate. The likes of the traditional figure of Olympias can be found virtually any night on television soap operas, wearing shoulder-pads, scheming, and making the plot go. In the past women so depicted were often royal-Eleanor of Aquitaine for instance - because royal women were often the only prominent women and certainly the only ones with a modicum of political power. What we have here is a kind of topos, which like many topoi continues to have powerful appeal. I shall refrain from considering exactly why we continue to be troubled by the association of women with power and why stereotypes associated with such women persist, but it is essential that we recognize and resist this fatal attraction.

- Elizabeth Carney, “Olympias and the Image of the Virago”

#historicwomendaily#history#olympias#alexander the great#macedonian history#ancient greece#mine#queue#ancient history

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

Your top 5 Alexander the Great moments?

Top Five Alexander Moments

One issue with answering this is to figure out what events actually happened, especially when it comes to anecdotes! Here are four I find either significant to understanding his charisma and/or which explain how he functioned and why he was successful, plus one I like just because I’m a horse girl.

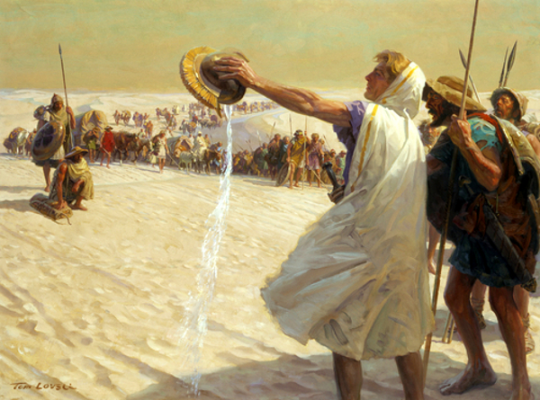

1) To my mind, the event that best illustrates why his men followed him to the edge of their known world occurred in the Gedrosian Desert. While I’m a bit dubious that this trek was as bad as it’s made out to be (reasons exist for exaggerating), it was still baaaad. One story relates that some of his men found some brackish water in a sad little excuse for a spring, gathered it in a helm, and brought it to him. Given his poor physical condition after the Malian siege wound, he no doubt needed it badly. He thanked them (most sincerely), then carried it out where all (or at least a lot) of his men could see, raised it overhead, and announced that until all of them could drink, he wouldn’t. Then he poured it onto the rocky ground.

That gesture exemplified his charisma. And it absolutely is not something the likes of a Donald tRump could even imagine doing—nor most dictators, tbh. They’d be blaming everybody else and calling for heads while drinking Diet Coke, not suffering alongside their people.

This wasn’t an isolated event of that type. While he almost certainly didn’t have time to engage along with his soldiers in every project, we’re told he would drop in from time-to-time, to inspire them and to offer a little friendly competition.

He also dressed like his men for everyday activities, especially early in the campaign. As time went on, some sources say he inserted more distance—probably necessary as his duties exploded—but he still seems to have found time to “just hang out” with his Macedonians on occasion. The claims that he was too high and mighty to do so appears to have been exaggeration (as such accusations often are) in order to forward a narrative that he was “going Asian.” Troop resentment over court changes was very genuine—I don’t want to underplay it (especially as I’ve written about it in a few chapters in this), but it tended to boil up during certain periods/events, then die back again. Alexander was trying to walk a very fine line of incorporating the conquered while not ticking off his own people.

2) Reportedly, he once threw a man out of line because he hadn’t bothered to secure the chin strap on his helm. I pick this one because it tells me a whole lot about how he saw himself as a commander, and what he expected of his men (and why he tended to consistently win).

On the surface, his reaction seems almost petty. It’s precisely the sort of mistake students whine about when professors ding them for it. It’s just a chin strap! I’d have tightened it before I went into battle! (It’s just a few typos; you knew what I meant! Or, Why does everything in the bibliography have to be exactly matching in style? Who cares? What a stupid thing to obsess about!) These objections are all of a piece. First, they’re lazy, and second, they indicate a disconcern with details. In battle, such disconcern can get a person killed. And on a larger scale, for a general, such disconcern loses battles.

One of the striking aspects of Alexander’s military operations was just how well his logistics worked. Consistently. We hear little about them precisely because they rarely fail. Food and water was there when they needed it, as were arrow replacements, wood to repair the spears, wool and leather for clothes and shoes, canvas for tents, etc., etc. All those little niggling (boring) details. If these are missing, soldiers become upset (and don’t fight well). Starting with Philip, the Macedonian military was a well-oiled machine. That’s WHY Gedrosia was such a shock: the logistics collapsed. Contra some historians, he did not do it to “punish” his men, nor to best Cyrus.* He had a sound reason—to scout a trade route.

Alexander understood that details matter. It starts with a loose chinstrap. (Or an unplanned-for storm and rebellion in his rear.) Everything else can unravel from that.

3) Alexander sends Hephaistion a little dish of small fish (probably smelts). He also helps an officer secure the lady of his dreams. And writes another on assignment (away from the army) that a mutual friend is recovering from an illness. While technically three “moments,” these are all of a piece. Alexander knows his men, and is concerned not only for their physical well-being, but also their mental state: that they’re happy. Granted, these are all elite officers, but it suggests he’s paying attention to people. I’ve always assumed he sent Hephaistion the fish because they were his friend’s favorite, and/or they were a special treat and he wanted to share. That he didn’t punish an officer for going AWOL to chase the mistress he wanted but offered advice, and even assistance, on how to court and secure her suggests the same care.

I don’t want to take away from what appears to be his serious anger management problems(!), but little details like those above strike me as the likeable side of Alexander—why his men were so devoted to him.

4) Then we have the encounter with Timokleia after the siege of Thebes. While probably a bit too precious to have occurred exactly as related, I think it may still hold a kernel of truth.

Alexander had a reputation of chivalry towards his (highborn) female captives. If some of that was likely either propaganda from his own time or philhellenic whitewashing later by Second Sophistic authors such as Plutarch (and Arrian), poor treatment of women is not something we hear attributed to him.

Ergo, while the meeting was probably doctored for a moral tail, he may well have freed Timokleia as an act of clemency to put a better face on a shocking destruction he knew wouldn’t sit well with the rest of Greece—who he both wanted to cow yet earn support from. (A difficult balancing act.) Also, if Timokleia hadn’t been high-born, she’d probably have been hauled off to one of the prisoner cages with little fanfare.

Nonetheless, I find his actions surprising given the casual misogyny of his era. If we can take the bare bones of the story as true, and it’s not all invented, Timokleia was raped as a matter of course during the sacking of Thebes, then managed to trick her rapist and kill him by pushing him down a well and dropping rocks on him. I assume this happened when his men weren’t there, but they found out soon enough and hauled her in front of Alexander to be punished for killing an officer. To the surprise of all, Alexander decided the man had earned it and freed Timokleia. One might be inclined to call this overly sentimental, but….

There’s a similar story that occurred much later in the Levant, when two of Parmenion’s men seduced/(raped?) the mistresses/wives of some mercenaries. Alexander instructed Parmenion to kill the Macedonians if they were found to be guilty.

In both cases, we have an affront against (respectable) women. In the latter case, Alexander was (no doubt) working to avoid conflict between hired soldiers and his own men, who—in typical Greek fashion—would have looked down on mercenaries as a matter of course. Some sort of conflict between Macedonians and Greek mercenaries up in Thrace had almost got Alexander’s father killed. Alexander saved him. No doubt that was on Alexander’s mind here.

Yet what both events illuminate is a willingness on Alexander’s part to punish his own men for affronts to honor/timē that involved women. Yes, this is clearly about discipline. But it also shows an unusual sensitivity to sex crimes in warfare: actions that would normally fall under the excuse of “boys will be boys” (especially when their blood is up).

I doubt he’d have felt the same about slaves or prostitutes; he was still a product of his time. Yet without overlooking his violence—sometimes extreme (the genocide of the Branchidai, for instance)—I find his reaction in these cases to be evidence of an atypical sympathy for women that I’d like to think isn’t wholly an invention of later Roman authors. And just might show the influence of his mother and sisters.

5) Last… the Boukephalas story…because who doesn’t love a good “a boy and his horse” tale? Obviously the Plutarchian version is tweaked to reflect that author’s later concern to contrast the Macedonian “barbarian” Philip with the properly Hellenized Alexander. Ignore the editorializing remarks, especially the “find a kingdom big enough for you” nonsense.

But the bare bones of the story seem likely: unmanageable horse, cocky kid, bet with dad, gotcha moment. You can imagine this was an anecdote Alexander retold a time or three, or twenty.

——

* His attempts to copy Cyrus may be imposition by later writers. In his own day, he may have cared more about the first Darius, for reasons Jenn Finn is going to explain in a forthcoming, very good article on the burning of Thebes and Persepolis.

#asks#Top Five Alexander the Great moments#Alexander the Great#Hephaistion#Hephaestion#Timoclea#Timoklea#Boukephalas#Bucephalas#Gedrosian Desert#ancient military logistics#Macedonian army#Alexander's logistics#Classics#ancient history#campaigns of Alexander the Great#tagamemnon

53 notes

·

View notes

Note

I’ve saw people saying that we don’t know if Cleopatra’s mother or paternal grandmother was black, so she could be mixed. What are your thoughs ?

My thought is very simple. If there is a line of ancestry we know about and a line of ancestry that we know nothing about and which could be black, brown or white again too, then you do the casting based on the part you know about and not the part you have no idea about. You do not eradicate the established historical fact for the sake of a pure hypothesis that flirts with wishful thinking and the cash-grabbing agenda trending in USA in 2023.

Also the Ptolemies were notorious for their intermarriages and most historians believe her mother was sister or cousin to her father 🤷🏻♀️ So from the get-go, this “documentary” loses any integrity.

#Cleopatra#anti Netflix#Macedonian Greek#ptolemies#Egyptian history#greek history#history#opinion#anon#ask

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alexander the Great in the Workshop of Apelles by Giuseppe Cades

#alexander the great#apelles#art#giuseppe cades#ancient greece#painter#painting#ancient greek#history#alexander#macedonia#macedonian#macedon#greece#greek#sculptures#sculpture#europe#european#classical antiquity#neoclassical#neoclassicism#artist#mediterranean

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hephaestion: Just tell me what happened.

Alexander: Okay but you have to promise you won't get mad.

Hephaestion: I promise.

Alexander: Ok so I was minding my own business-

Hephaestion: Bullshit!

Alexander: I was!

#macedonian sillys#alex just committed another arson nothing to worry about#just another regular day#also he can't mind his own business his petty ass just can't#alexander of macedon#alexander the great#ancient greece#ancient history#greek history#classical greece#classical history#hephaestion

107 notes

·

View notes