#prefigurative politics

Text

When incorporating disability into your politics, it is good to remember that the allocation of resources is one of the central questions that divides political ideologies. It is the “why”, whereas most of the other questions are sorting out the “how”.

I think one of the core tensions that plays out between disability movements and other liberatory movements is that knowledge of disability fundamentally reshapes how you understand the allocation of resources. In one sense, to be disabled is to need resources allocated to you because you cannot get them on your own.

•Disabled people know, experientially, that we need flattened hierarchy; the hierarchies of the medical establishment kill us and further disable us. They strip away our access to the resource that is medical knowledge and medical care.

•We know that we need an ecological relationship that is sustainable and stable, because the current eugenic environmental management system is sometimes the cause, and more often the exacerbator, of our disability. But also because we know that the scarcity of resources it is progressively creating will kill us first

•We know that we need continual industrial production to maintain the means by which we can be diagnosed and treated, and that even a short term collapse of production will kill many of us.

•we also know that there must be a fundamental reorganization of all society because we know that the current organization is also killing us, and that methods of gradual change will not prioritize us, and that many of us will be dead by malice or neglect before they come into effect.

•we know that we need ongoing, active care to survive.

•we know that a society cannot meet the needs of those whose needs it does not understand. We know that any plan for meeting needs, or granting rights, or ensuring values must explicitly include us, because we know that the nature of disability is that things do not work the same for us as they do for others.

The lived experience of disabled people creates a direct challenge to the ideas of resource allocation that those with less experience have developed. We see the gaps in their proposals because we know we are the ones who will fall through them. It is easy for an abled political theorist to say “we will work it out when we get there”. But someone who will die with 2 missed doses? they must say “will we get there?”

This question is often met with dismissal, for understandable reasons. At its heart, the existence of the disabled reminds the theorists that their ideas are incomplete.

But, for a moment, I would ask you to consider us a prompt, instead of a threat. Yes, we can point to the gaps in your ideology. But we are not doing this to hurt you, or even to say you are wrong. We point to the gaps because we want to help you fill them.

So, political thinkers, take a moment to imagine your world. Imagine the look, the feel, the smell. Think of your social relations, your food, your housing. Conjure up every beautiful dream for society that you’ve built.

Now ask yourself

1. In this society, how would someone get their medication reliably, Every single day? How can they ensure the quality and safety of that medication?

2. In this society, how would someone seek information about what’s wrong in their body? Are there widely available high-tech diagnostics, like MRI machines? (Bonus question: how does your society go about inventing and creating new high tech diagnostics?)

3. How would someone who cannot move their body bellow their neck get around. How would they get food, water, shelter, socialization, and freedom to leave their domicile and participate in the world?

4. How would someone who cannot read, write, or speak due to intellectual disability be able to live, and to have meaningful access to all the things that you believe humans deserve in your society?

5. In trying to build this society, transitioning from our current world to this new one, how would the people mentioned in above questions survive the transition?

And try to answer these questions. It’s okay if you don’t know right away. It’s okay if you have to think about it, do some research, or talk to some people. You love dreaming about the world we could build, right? This is more information for you to develop and refine that dream.

These questions are not exhaustive, at all. But they are a good starting point to check for gaps in your plan for reality, and to see who is currently falling through.

#text post#disability#long post#politics#prefigurative politics#anarchism#cpunk#socialism#communism#leftism#rose baker#disabled#liberation#utopia#cripple punk

152 notes

·

View notes

Text

i'm not sure about dialectical materialism...

I spend a lot of time talking about strategies and frameworks for IRL worldbuilding. This can be a bit problematic for a lot of reasons. I’ll start by looking at two: a “democratic centralist” ideological lineage that I disagree with, and a different, more insurrectionary response to that tendency. Now, that is something I have much more respect for, but don’t see it as being able to carry the torch the whole way.

I am someone who sees the importance and benefits of strategic thinking but also understands the negation-oriented spontaneity of uprisings, direct actions, and isolated confrontations. I don’t want (nor do I think it’s possible for) those things to stop, but I want them to be as effective as possible. This means that more people need to become collaborative and autonomous (in the self-directed, can-make-decisions-for-themselves sense). We have to organize around this, and we need a strategy so that we can both make it happen and iterate more successfully.

That’s all I’ll say about that section of things. Anti-organization/anti-strategic folks are dope, but they can’t get us all the way. The best case is that they widen the spaces for autonomy to flourish. The main thing I want to focus on is people who strategize and organize in a centralized way. I’m going to discuss dialectical materialism as it is conceived, and why I think that it blows.

Let’s talk about dialectics and materialism separately for a bit. Dialectics is a way to think about the world, a kind of mental model builder, that allows one to analyze tensions (or contradictions) in society and resolve them in a way more satisfactory than either choice. It is an undergirding idea that can animate further thoughts. Materialism, meanwhile is that the material world/reality itself is what promotes history and social development. Ideas aren’t what make history move, it’s the material conditions. So, the way that they are combined, becoming the philosophy of dialectical materialism is meant to be a framework to allows us to understand and critique society so that we can make it more liberatory.

Dialectical materialism is an idea that I’ll mostly attribute to Stalin that sees social change and history through understanding contradictions and material circumstances. It’s meant to understand the base of society, which is the economic mode of production, and the superstructure, which is everything that is birthed from that economic mode of production. So things like culture, art, ideology, etc. Base = economics, Superstructure = the rest of the pieces of society. Got it?

While this may sound great, dialectical materialism as a framework has some glaring blind spots. People don’t act purely from a place of rationality or determinism based on their conditions. Said otherwise, you cannot look solely at material conditions and understand why the world is why it is, or why people act the way that they do. We have to dialectically (ha) look at the tension between materialism and idealism, analyzing both of their places in the world. With this in mind, the way that dialectics are bundled with materialism (creating the philosophy of dialectical materialism) claims scientific rigor without proving it through a relationship of experimentation and iteration. There isn’t enough empirical evidence to support this conception of dialectical materialism.

It leaves me to question whether or not a more holistic, systems & complexity-oriented method/philosophy can surpass dialectical materialism. Complexity theories, namely the ideas of self-organization, emergence, chaos, and entropy are exciting and interesting ways to see how social change works. Rather than a simple machine, societies are complex adaptive systems that are more than just resolving tensions between contradictions. A useful mental model builder is DSRP (Distinctions, Systems, Relationships, and Perspectives) structures. Distinctions are about looking at the elements/agents within a system, where identifying one element implies the existence of other elements. Systems are an understanding whole that necessitates parts. Relationships are the actions and reactions between the other structures (Distinctions, Systems, other Relationships, and Perspectives). Perspectives are specific positions/points, implying a view. Using DSRP, we can construct models of systems and understand them on a holistic level, rather than reducing the fidelity of our analysis to our detriment. DSRP, similarly to dialectical materialism, is a fractal tool, creating as little or as much fidelity as we would like in our models.

I think that the most damning thing for dialectical materialism is a lack of understanding of how power functions within both the base and the superstructure, influencing and steering social forces. Power is a relationship between both people and their positions within a society. By not questioning the form that power takes (power-over vs. power-to vs. power-with), it cannot actually resolve the contradictions within society meaningfully. It undermines the whole project. We need to unpack the multifaceted nature of inequality, relating to all of the vectors that identity exists (race, gender, ability, sexuality, etc.) and seeing their relation to the structure as both of and from that structure. How social discourses, institutions, and practices reinforce matrixes of domination is very important to understand.

But maybe this doesn’t mean that we fully discard dialectics and materialism. I see them as something that can complement complexity theory and a liberatory power analysis. Dialectics are a great way to look at shifting terrains and sites of struggle, based on our understanding of the complex adaptive system of society. We also need to understand the material world, which benefits from a holistic scientific framework like understanding complexity. Ecosystems (a descriptive, holistic science) are a much more useful touchstone for understanding society than physics (a prescriptive, reductionist science). Oppressive ideas come from material conditions and are shaped by power structures. We could critically employ dialectical materialism to get a fuller picture, but that comes from being in concert with other tools.

Instead of fully abandoning it, we can integrate some of the most useful insights from dialectics and materialism, blending them into more modern systems analysis and theories of power. This has to be done in concert with those marginalized by society. Fuddy-duddies are the ones who have bungled everything, so it’s time to pass the torch. If we can do this, if we can empower the folks on the furthest margin, they will be able to emancipate themselves with a theory that simultaneously facilitates a building of dual power, contesting oppressive power, and ushering in a new world.

#economics#economy#econ#anti capitalists be like#neoliberal capitalism#late stage capitalism#anti capitalism#capitalism#activism#activist#direct action#solarpunks#solarpunk#praxis#socialism#sociology#social revolution#social justice#social relations#social ecology#organizing#complexity#resist#fight back#organizing 101#radicalization#radicalism#prefigurative politics#politics#mobilize

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

You must believe that the world is going to change. You must believe that you can change it. Not alone, like some ruggedly individualist caped superhero, but as part of a mass movement, a superorganism, a shared heart, a moment of unity. You must trust that your actions matter, even when they don’t. You must remember that even if going to a protest or opening your doors to the desperate or giving up hyperpconsumption cannot alter the wider societal patterns if only you undertake to do so, that you are just one drop of water in an ocean. And it will change you. That is often the first step. You must believe that one day all the fossils will stay in the ground. You must believe that one day war will be a distant memory. You must believe that one day women will dance in the streets at night unafraid. You must believe that one day land will belong to everyone and queer liberation will be achieved. You must believe it. Even if your great-grandchildren do not live to see it done. Prefiguration is praxis. It’s therapy. It’s all we have.

#solarpunk#hopepunk#environmentalism#social justice#optimism#community#bright future#prefiguration#politics

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

There were two central issues at Columbia: the question of divestment and that of university decision-making. The heart of the divestment argument is that money changes things. If economic sanctions against South Africa were pursued with the vigor of, say, the destabilization of the democratically elected government of Allende in Chile, the regime might well be prevented from prosecuting the war in Namibia, and forced into negotiating with the African National Congress. Divestment, as an act of solidarity with the black trade unions and the United Democratic Front in South Africa, can help make South Africa ungovernable. [...] As the Columbia Coalition points out, "IBM is still supplying computers which keep track of blacks under the pass law system, Mobil is still providing oil to the South African military, and all companies are still obliged under the Key Points Act to offer their factories to the military in case of black unrest. " At present, Columbia's investment policy looks more and more like the Reagan administration's "constructive engagement "-which has meant backing IMF loans to South Africa, sending 2,500 electric shock batons to apartheid's police, and encouraging American investment. Indeed the changes that have taken place in South Africa-like the heavily-boycotted "Coloured" and Asian Parliaments-are, as Stanley Greenberg of Yale's Southern Africa Research Program has argued, signs not of the success of "constructive engagement" but of the vulnerability of the apartheid regime.

But the Columbia blockade was not only about divestment: since the University Senate had unanimously voted for full divestment, the blockade focused attention on the unaccountability of the university trustees. In the course of the blockade, two visions of the university came into conflict: on the one hand the humanistic ideal of the university as a community, which, if not quite democratic, still recognizes the rights and responsibilities of its several bodies-faculty, students, staff, alumni; and on the other hand, the reality of the university as a real estate corporation, directed by a corporate board, increasingly dependent on corporate monies, and selling a service to student consumers. Students at Columbia became particularly aware of the second Columbia-Columbia Inc.-when the administration bitterly resisted recognizing the clerical union earlier this school year. They have seen it again in the trustee's resistance to the university community's decision for divestment. And during the blockade, the support from community and tenants groups included an education about Columbia as landlord and gentrifier. The various lived experiences of the corporate university was the ground for the reciprocal support between students and clerical workers, and for the two major marches: one from Harlem to Hamilton Hall, the other from Hamilton Hall to Harlem. As Tanaquil Jones of the Coalition said, "We're going to give back to the Harlem community what they've given us."

[...] The Columbia blockade sparked sit-ins, demonstrations and arrests at cam puses across the country: among them, Berkeley, Rutgers, Purchase, Cornell, Princeton, Santa Cruz, and Syracuse. Though each of these has their own history and internal dynamics, and all of them, including Columbia, are part of a larger history of actions against American support for apartheid, the events of April do provoke the question: "why divestment? " The divestment movement has uniquely condensed the unquestioned opposition to the apartheid regime of the mass of students, a focus on a specifically university issue of investment, and, perhaps most strikingly, the possibility of multiracial action, the prefigurative politics of a rainbow coalition.

Michael Denning, Money Changes Everything: The Divestment Bockade at Columbia Inc. (1985)

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

I do think that the opposition to veganism / reactionary mocking and condemnation of multispecies-justice oriented practices will escalate as does collective awareness (in the global northwest) that 1) the most extreme effects of climate disaster hitherto imaginable are and have been happening right here and now and 2) it becomes less and less possible to obfuscate the uniquely violent - on individual and collective levels - practices and systems that structure our food system, for all species involved.

Put simply, even progressive political voices seek an “endpoint” to their politics, after which they are finally freed from caring / making necessary personal changes to prefigure/assist in collective social transformation. So yeah, you’re going to get a lot of people screeching about the futility of what they call “consumer activism,” or unsolicited diatribes against “stupid vegans” doing this or that. It’s the screech of a guilty conscience, of unresolved tensions, of the embedded knowledge that at the end of the day, collective transformation requires individual sacrifice and discomfort, and vegans are far more equipped in said practices of sacrifice and accommodation than we’re given credit for.

161 notes

·

View notes

Text

Radical feminism remained the hegemonic tendency within the women's liberation movement until 1973 when cultural feminism began to cohere and challenge its dominance. After 1975, a year of internecine conflicts between radical and cultural feminists, cultural feminism eclipsed radical feminism as the dominant tendency within the women's liberation movement, and, as a consequence, liberal feminism became the recognized voice of the women's movement.

As the preceding chapters have shown, there were prefigurings of cultural feminism within radical feminism, especially by 1970. This nascent cultural feminism, which was sometimes termed ‘female cultural nationalism’ by its critics, was assailed by radical and left feminists alike. For instance, in the December 1970 issue of Everywoman, Ann Fury warned feminists against "retreating into a female culture":

“Like other oppressed [sic], we have our customs and language. But this culture, designed to create the illusion of autonomy, merely indicates fear. Withdraw into it and we take our slavery with us. . . . Furthermore when we retreat into our culture we cover our political tracks with moralism. We say our culture is somehow "better" than male culture. And we trace this supposed superiority to our innate nature, for if we attributed it to our powerlessness, we would have to agree to its dissolution the moment we seize control. . . . When we obtain power, we will take on the characteristics of the powerful. . . . We are not the Chosen people.”

Similarly, in a May 1970 article on the women's liberation movement in Britain, Juliet Mitchell and Rosalind Delmar contended:

“Re-valuations of feminine attributes accept the results of an exploitative situation by endorsing its concepts. The effects of oppression do not become the manifestations of liberation by changing values, or, for that matter, by changing oneself—but only by challenging the social structure that gives rise to those values in the first place.”

And in April 1970, the Bay Area paper It Ain't Me, Babe carried an editorial urging feminists to create a culture which would foster resistance rather than serve as a sanctuary from patriarchy:

“It is extremely oppressive for us to function in a culture where ideas are male oriented and definitions are male controlled. . . .Yet the creation of a woman's culture must in no way be separated from the political struggles of women for liberation. . . . Our culture cannot be the carving of an enclave in which we can bear the status quo more easily—rather it must crystallize the dreams that will strengthen our rebellion.”

But these warnings had little effect as the movement seemed to drift almost ineluctably toward cultural feminism. Cultural feminism seemed a solution to the movement's impasse—both its schisms and its lack of direction. Whereas parts of the radical feminist movement had become paralyzed by political purism, or what Robin Morgan called "failure vanguardism," cultural feminists promised that constructive changes could be achieved. To cultural feminists, alternative women's institutions represented, in Morgan's words, "concrete moves towards self determination and power" for women. Equally important, cultural feminism with its insistence upon women's essential sameness to each other and their fundamental difference from men seemed to many a way to unify a movement that by 1973 was highly schismatic. In fact, cultural feminism succeeded in large measure because it promised an end to the gay-straight split. Cultural feminism modified lesbian-feminism so that male values rather than men were vilified and female bonding rather than lesbianism was valorized, thus making it acceptable to heterosexual feminists.

Of course, by 1973 the women's movement was also facing a formidable backlash—one which may have been orchestrated by the male-dominated New Right, but was hardly lacking in female support. It is probably not coincidental that cultural feminism emerged at a time of backlash. Even if women's political, economic, and social gains were reversed, cultural feminism held out the possibility that women could build a culture, a space, uncontaminated by patriarchy. Morgan described women's art and spirituality as "the lifeblood for our survival" and maintained that “resilient cultures have kept oppressed groups alive even when economic analyses and revolutionary strategy fizzled.” There may even have been the hope that by invoking commonly held assumptions about women and men, anti-feminist women might experience a change of heart and join their ranks. The shift toward cultural feminism also suggests that feminists themselves were not immune to the growing conservatism of the period. Certainly, cultural feminism's demonization of the left seemed largely rooted in a rejection of the '60s radicalism out of which radical feminism evolved.

-Alice Echols, Daring to Be Bad: Radical Feminism in America: 1967-75

#Alice Echols#feminist history#radical feminism#cultural feminism#liberal feminism#womens history#second wave feminism

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the mass protest decade, street explosions created revolutionary situations, often on accident. But a protest is very poorly equipped to take advantage of a revolutionary situation, and that particular kind of protest is especially bad at it. If you believe that you can forge a better society, if you are willing to run the risk of trying, then you should enter the vacuum yourself. But a diffuse group of individuals who come out to the streets for very different reasons cannot simply take power themselves, at least not as an entire diffuse group of individuals. Once someone goes in there and takes power in the name of the masses, you are talking about a type of vanguard—a particular ideological project, and a minority of people who dare to try to represent the rest of the population. In some of the more utopian strains of anti-authoritarian thought, the riot is supposed to become the new society, but this has not worked out so far.11 Perhaps it might, someday, but it would probably not work very well in the actually existing Global South, which is surrounded by so many foreign actors that might be sucked very quickly into an apparent power vacuum by the possibility of easy profit and plunder.

If some new group boldly steps into the vacuum, manages to stay there, and transforms society, then that’s a revolution. But if you find your political system broadly acceptable, or you don’t think you can replace it with something better, then the thing to do is to negotiate. That is called reform. You can use your power on the streets to extract concessions, if you play it right. But once more, this necessarily entails representation.

It was not just Mayara and Haddad who overlapped in their answers to my question. I heard it very often—it came in different forms, but I heard it more than any other response. I think Hossam Bahgat put it best, or at least, the most directly.

“Organize. Create an organized movement. And don’t be afraid of representation,” he said without hesitation, in his office in Giza, as his world fell apart around him. “We thought representation was elitism, but actually it is the essence of democracy.” I heard answers like this over and over, confirming research compiled by scholars. As early as 1975, William Gamson found that movements succeed more often when they deploy hierarchical forms of organization. In a wide-ranging 2022 study, Mark Beissinger found that loose uprisings of the Maidan type tend to increase inequality and ethnic tensions, while they do not consolidate democracy or end corruption.

“After Maidan, I decided I do not believe in self-organization,” said Artem Tidva, the young leftist who brought a red European Union flag to the square, as we grabbed a bite to eat in central Kyiv in the summer of 2021. “I used to be more anarchist. Back then everyone wanted to do an assembly; whenever there was a protest, always an assembly. But I think any revolution with no organized labor party will just give more power to economic elites, who are already very well-organized.” Unlike some of his former comrades, Artem never gave up on the Ukrainian uprising and stayed active in the post-Maidan political scene, working to push for center-left, anti-racist alternatives in the context of the new political order. But in Ukraine, it seemed clear that the uprising had benefited the groups that had already formed coherent, disciplined organizations before the uprising began, and we had seen more evidence of that earlier in the day.

“I definitely don’t have the same views on these things as I did before 2013,” said Lucas “Vegetable” Monteiro. He still believes that a better society must be born out of this one, not just created after some revolution seizes state power. But he now thinks that the Movimento Passe Livre turned the principles of horizontalism, autonomy, and prefiguration “into a dogma, into a kind of religion, and we could not turn them into real political practice. Instead, they became a kind of identity. And we ended up quickly crashing into barriers that we ourselves had created.” The MPL still exists, but no one who was in the group in 2013 is still a member. Looking back on 2019 in Hong Kong, Theo told me, “[It] was very fun to see the China building defaced, I had a lot of fun on the streets, but the decentralized nature of the movement meant that there was no room for discussion about how it should work, or how a coherent strategy could be developed.”

Not everyone I met came out of the decade adopting positions in favor of formal structures, in support of “verticalism” and hierarchy, insisting that representation matters. Mayara, for example, remains mostly true to the ideals she adopted as a young punk. But everyone moved in the same direction. I spent years doing interviews, and not one person told me that they had become more horizontalist, or more anarchist, or more in favor of spontaneity and structurelessness. Some people stayed in the same place. But everyone that changed their views on the question of organization moved closer to classically “Leninist” ones.

Bevins, Vincent. If We Burn: The Mass Protest Decade and the Missing Revolution

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

THIS DAY IN GAY HISTORY

based on: The White Crane Institute's 'Gay Wisdom', Gay Birthdays, Gay For Today, Famous GLBT, glbt-Gay Encylopedia, Today in Gay History, Wikipedia, and more … March 5

1534 – On this date the Italian painter Correggio died (b. 1489). Born as Antonio Allegri Correggio in Parma, he was the foremost painter of the Parma school of the Italian Renaissance, who was responsible for some of the most vigorous and sensuous works of the 16th century. In his use of dynamic composition, illusionistic perspective and dramatic foreshortening, Correggio prefigured the Rococo art of the 18th century. According to some sources he was born in 1494.

Correggio infused all of his figures—male and female alike—with an intense voluptuousness that transcends any limitations of gender. His depiction of exquisite androgynous youths has made him a favorite among gay male viewers in the modern era.

Danaë

Among prominent homosexuals in late nineteenth-century Britain, Oscar Wilde shared admiration for Correggio's art with John Addington Symonds , and Wilde sought out his paintings during his trip to Italy in 1875. The homoerotic qualities of Correggio's paintings have continued to be appreciated by gay viewers in recent decades.

Frequently included in lists of famous gay historical figures, Correggio is among the fifty-two individuals whose name is recorded on Into the Light, the mural covering the dome in the Gay and Lesbian Center of the San Francisco Public Library.

Correggio's The Rape of Ganymede was the first large-scale Renaissance oil painting of the subject. Correggio shows Jupiter, in the guise of an eagle, lifting the shepherd boy high above the lush blue-green landscape, while a dog jumps excitedly up toward his young master.

The Rape of Ganymede

With his face encircled by soft curls, Ganymede gazes out seductively at the viewer, even as he embraces the eagle. The dark feathers of the eagle help to set off the glowing pink flesh tones of the youth, who is shown at a three-quarter angle with much of his backside visible. Wind blows the pink draperies away from Ganymede's smooth, radiant buttocks, so that these are fully exposed to the viewer. Jupiter's understandable attraction to the beautiful youth is revealed by the way that the eagle tenderly licks at the boy's wrist.

The early acknowledgment of Correggio's Ganymede as a quintessential representation of homoerotic desire is indicated by the numerous references to the painting in the proceedings, conducted by the Spanish Inquisition against the wealthy connoisseur Antonio Pérez (1534-1611) on charges of sodomy. During the lengthy trial (which lasted from 1579 until 1590, when Pérez escaped to France), his ownership of Correggio's Ganymede was repeatedly cited as proof of his inclination to commit homosexual acts.

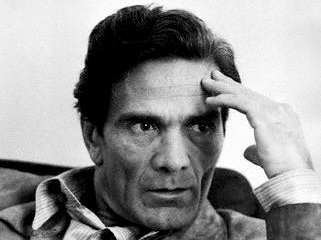

1922 – the Italian poet, intellectual, film director, and writer Pier Paolo Pasolini, was born on this date (d. 1975). Pasolini distinguished himself as a philosopher, linguist, novelist, playwright, filmmaker, newspaper and magazine columnist, actor, painter and political figure. He had a unique and extraordinary cultural versatility, and in the process became a highly controversial figure.

While openly Gay from the very start of his career (thanks to a sex scandal that sent him packing from his provincial hometown to live and work in Rome), Pasolini rarely dealt with homosexuality in his movies. The subject is featured prominently in Teorema (1968), where Terence Stamp's mysterious God-like visitor seduces the son of an upper-middle-class family; passingly in Arabian Nights (1974), in an idyll between a king and a commoner that ends in death; and, most darkly of all, in Salò (1975) [banned in many countries throughout Europe and North America], his infamous rendition of the Marquis de Sade's compendium of sexual horrors, The 120 Days of Sodom.

In 1964 he found his public moviemaking "voice" with The Gospel According to St. Matthew. With a non-professional cast and a quasi-documentary shooting style, Pasolini retold the familiar story of the life of Christ in the simplest, least-Hollywood-like style imaginable.

For a time a Christian fundamentalist film distributor had the rights to the film in the United States and successfully exhibited it to church groups. One wonders how receptive the fundamentalist audience would have been to the movie had they known that its maker was a gay, atheistic communist.

Gospel was followed by The Hawks and the Sparrows (1966), a comic fable about the adventures of a Chaplinesque father and son team, played by the great Italian star Toto and Ninetto Davoli, a young former lover of Pasolini's who was to appear in many of the filmmaker's works.

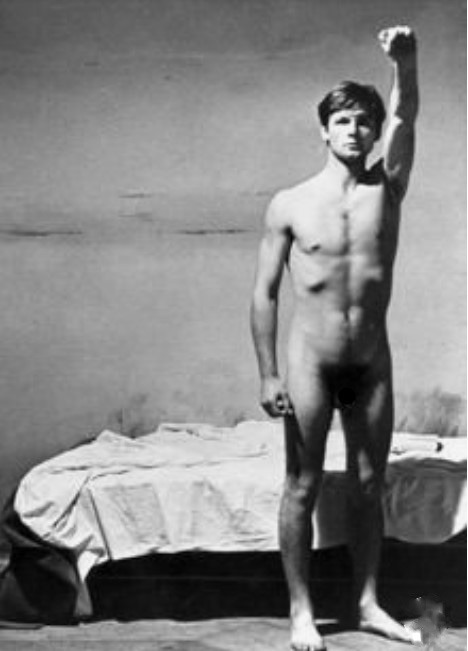

a scene from Pasolini's Salò

His most visually elegant and dramatically reserved work, Salò offers Sade's vision of old, wealthy, evil authorities (politicians, lawyers and bishops) having their way with nude and compliant youths and maidens of the lower classes as simply standard operational procedure for the powers that be.

Pasolini was open about his sexuality, his Communism, his compassion for the poor, the delinquent, and the young. He once wrote a poem for the dying Pope Pius XII that read, in part:

How much good you could have done!

And you

Didn't do it.:

There was no greater sinner than you

Pasolin's own death was a terribly banal sort of death. As far as the heterosexual status quo is concerned, Pasolini, a wealthy, older, and therefore "corrupt" man was killed by a poor and therefore "innocent" youth "disgusted" by his "advances." But, as every gay man knows, this homophobic scenario is never really the truth.

Pasolini's death (which involved the killer or killers driving over the artist's head with his own car) was a gay-bashing as certainly as was that of Matthew Shepard. The difference is that in 1975 the cultural climate was not as sympathetic to the spectacle of the death of an intellectual as it proved to be in 1998 with the death of a gay college student.

1932 – Michael Rumaker is an American author best known for his semi-autobiographical novels that document his life as a gay man in the 1950s and after.

Rumaker graduated from Black Mountain College in 1955 and later wrote a memoir of his time there. He hitchhiked to San Francisco where he encountered the literature of the Beat Generation. Returning to New York, he attended Columbia University and received an MFA in 1969, after which he began teaching writing.

His first book, The Butterfly, is a fictionalized memoir of his brief affair with a young Yoko Ono, published before Ono became famous. His short stories, Gringos and other stories, appeared in 1967. A revised and expanded version appeared in 1991. He began to write directly about his life as a gay man in the volumes A Day and a Night at the Baths (1979) and My First Satyrnalia (1981). The novel Pagan Days (1991) is told from the perspective of an eight-year old boy struggling to understand his gay self. Black Mountain Days, a memoir of his time at Black Mountain College, has a strong autobiographical element. In addition, there are portraits of many students and faculty (including the poets Robert Creeley, Charles Olson and Jonathan Williams) during its last years, 1952-1956.

Following his graduation from Black Mountain College, Rumaker made his way to the post-Howl, pre-Stonewall riots gay literary milieu of San Francisco, where he entered the circle of Robert Duncan. His account of that time in the book Robert Duncan in San Francisco gives an unvarnished look at the premier poet of the San Francisco Renaissance. Rumaker will release previously unpublished letters between himself and Robert Duncan for a new edition, published by City Lights.

1947 – Michael Mason (d.2015) was the news editor of Gay News who went on to co-found and edit the pioneering London paper Capital Gay and was a leading figure in the campaign for homosexual law reform.

Having been born in an era when homosexuality was illegal, Mason was bemused towards the end of his life to see a Conservative prime minister fighting for gay marriage. But, without his own tireless groundwork , such changes might not have happened.

Michael Aidan Mason was born in London. His father, Kenneth, was a Fleet Street journalist who later founded his own publishing house specialising in marine books.

Michael was sent as a weekly boarder to prep school in Surrey, then to Lancing College where, as well as singing in the chapel choir, he trysted happily with willing partners in the space below the school stage. It was there that he was discovered in flagrante while he was house captain.

Fortunately this did not derail his school career, and he went on to read Law at St Edmund Hall, Oxford.

In the early 1970s he encountered the Gay Liberation Front, the radical movement which offered gay people an alternative, more open, way of life to the furtive existence they had led hitherto. It completely changed his world view and he became a GLF activist.

The GLF dissolved and fragmented within a couple of years, but one of the fragments was Gay News, a hippie-style fortnightly. Excited by the concept of a gay newspaper, Mason got a job as business manager and within six months was news editor.

In 1981 Mason and his colleague Graham McKerrow broke away to set up a London-only paper called Capital Gay.

When a mystery sickness began claiming the lives of gay men in New York and San Francisco, Capital Gay appointed a medical columnist. The publication is credited by the Oxford English Dictionary as the world’s first to use the term HIV. It was ahead even of science journals, and British doctors read it to get information about the new disease from the United States. The prompt alert it offered is one reason Aids casualties were relatively low in London.

Mason’s proudest memory was being received at Grace Cathedral in San Francisco by the city’s mayor, Diane Feinstein, and asked to lead that year’s Pride parade. His lover Carl Hill had been arrested at immigration for wearing a gay badge while they were travelling to cover the event. They had become a cause célèbre, and this was San Francisco’s bid to atone.

After a decade with Carl Hill, he had a long-term relationship with David White, who later emigrated to Australia.

When Capital Gay finally collapsed in 1995 after a series of burglaries, Mason went to work as a legal secretary in a south London firm specialising in lesbian and gay immigration cases.

Soon after retirement, he was diagnosed with lung cancer which spread to his throat and his brain.

1990 – Matt Rogers is an American comedian, actor, writer, podcaster, and television host. He is best known for co-hosting the pop culture podcast Las Culturistas with Bowen Yang since 2016.

Rogers was born and raised on Long Island, New York. Rogers attended Islip High School and was named prom king at his senior prom. After graduating, he earned a BFA in Dramatic Writing from New York University. While studying, Rogers became a member of the improvisational group Hammerkatz and started studying at the Upright Citizens Brigade in 2009. It was while at NYU that Rogers first met Yang.

While studying at UCB, Rogers performed in several shows, including Characters Welcome and Amazing Welcome; he also performed in the Maude team and served as the artistic director of the musical sketch comedy group Pop Roulette. In 2016, Rogers was recognized as a "Comic to Watch" by Comedy Central. Since 2016, Rogers has co-hosted the podcast Las Culturistas with fellow NYU alumnus Bowen Yang

In 2020, Rogers hosted two television competition series. Gayme Show, co-hosted with Dave Mizzoni, was based on a popular comedy night in which straight men were quizzed on queer culture; the show aired for one season on the streaming platform Quibi. After initially being renewed for a second series, the show's current status remains in limbo following the closure of Quibi in October 2020. Also in 2020, Rogers became the host of Haute Dog, which aired on HBO Max and saw dog groomers compete for a cash prize.

As an actor, Rogers has made guest appearances on multiple television series, including Shrill, Awkwafina Is Nora from Queens, and Search Party. In 2021, it was announced that Rogers would have a starring role on the comedy series I Love That for You, in addition to a supporting role in the film Fire Island, a gay retelling of Pride and Prejudice.

He is gay, having come out while a student at NYU.

2007 – The first US soldier to be injured in the Iraq conflict, Marine Staff Sgt. Eric Alva, came out and announced his opposition to the US armed forces' "Don't ask don't tell" policy on homosexuality.

Today's Gay Wisdom:

Pier Paolo Pasolini

Pasolini, as he appeared in his own "The Decameron."

If you know that I am an unbeliever, then you know me better than I do myself. I may be an unbeliever, but I am an unbeliever who has a nostalgia for a belief. - Pier Paolo Pasolini

The mark which has dominated all my work is this longing for life, this sense of exclusion, which doesn't lessen but augments this love of life. - Pier Paolo Pasolini

One should never hope for anything. Hope is a thing invented by politicians to keep the electorate happy. - Pier Paolo Pasolini

I suffer from the nostalgia of a peasant-type religion, and that is why I am on the side of the servant. But I do not believe in a metaphysical god. I am religious because I have a natural identification between reality and God. Reality is divine. That is why my films are never naturalistic. The motivation that unites all of my films is to give back to reality its original sacred significance. - Pier Paolo Pasolini

Power has two ways of bringing racist hatred against the poor. The first point: leave them poor and a poor person comes to be hated. Make them policemen and they're accused of being killers. The moment a poor person becomes a killer he's open to racist hatred. This is horrible, we shouldn't experience this. I am obviously against the police. It's the arm upon which every power structure is built. And the power structure always tends towards the Right. I do, however, refuse to share in any type of racial hatred. - Pier Paolo Pasolini

I've never talked about the importance of the family, I'm against the family, the family is an archaic Remnant. During my childhood I had certain conflicts with my family whose background was definitely middle-class. My father represented the worst element I could imagine. It's rather difficult to talk about my relationship with my father and mother because I know something about psychoanalysis. What I can say is that I have great love for my mother. My origins are fairly typical of petty bourgeois, Italian society. I'm a product of unity of Italy as a Republic. - Pier Paolo Pasolini

I've stated various times that "Oedipus Rex" is an autobiography: my father who was an officer and my mother was more or less the woman played by Silvana Mangano. I live the Oedipus complex in a kind of laboratory fashion, in an almost elementary and schematic way. - Pier Paolo Pasolini

When I make a film I'm always in reality, among the trees and among the people; there's no symbolic or conventional filter between me and reality as there's in literature. The cinema is an explosion of my love for reality. I have never conceived of making a film that would be a work of a group, I've always thought of a film as a work of an author, not only the script and the direction but the choices of sets and locations, the characters, even the clothes. I choose everything, not to mention the music. - Pier Paolo Pasolini

From Pier Paolo Pasolini's, Roman Poems:

I WORK ALL DAY...

I work all day like a monk

and at night wander about like an alleycat

looking for love... I'll propose

to the Church that I be made a saint.

In fact I respond to mystification

with mildness. I watch the lynch-mob

as through a camera-eye.

With the calm courage of a scientist,

I watch myself being massacred.

I seem to feel hate and yet I write

verses full of painstaking love.

I study treachery as a fatal phenomenon,

almost as if I were not its object.

I pity the young fascists,

and the old ones, whom I consider forms

of the most horrible evil, I oppose

only with the violence of reason.

Passive as a bird that sees all, in flight,

and carries in its heart,

rising in the sky, an unforgiving conscience.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

If you look towards any unalienated/semi-alienated community in the world, the most unifying aspect is always food and we know intuitively just how important food is. This shared cuisine of people is rooted really in a shared mode of subsistence and a shared way of place-specific life. The movement of civilization is the uprooting of these ways of life; of place-specificity; and replacing it with a unified, homogeneous food culture based around a surplus of a select few crops. Ethnic cuisine ultimately becomes a relic, a memory of ways of life being lost.

In countercultural circles the prevalence of veganism speaks to the desire for a new food culture; the critique of the animal husbandry is less important than the ties that construct a vegan counterculture. Ultimately it is a consumer lifestyle choice, a simplified critique that mobilizes our predisposition to acknowledge taboo, reinforce stigma and moralize feelings of disgust. In the communal house the sharing of homogenized lentil and rice dishes is imagined as prefigurative politics in the kitchen but its really more like Sumerians lining up to fill their grain rations or devotees taking communion.

The person who overcomes taboo and develops a taste for cockroaches has achieved more than this communal house; they found a way to commune directly with the inhabitants of their city and subsist in spite of sealed-away soil. Every self-subsisting community that eats what it does has developed a cultural adaptation to their environment and one of the primary aims of civilization on its frontier is destroying that capacity to commune with and therefore adapt to and inhabit the land beneath us.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Amid the gritty heroism of the Edain, it is easy to think of them primarily as a people who arrived and became allied in the fight against Morgoth, a mission that prefigures Aragorn's role much later in the legendarium. Amlach is an intriguing character because he hints at the complexity of the political situation that lurked behind the rapid-fire and often aggrandized history that is The Silmarillion. Initially a skeptic in Marach's embrace of the Elvish mission against Morgoth, Amlach's mind is changed when he is the victim of a particularly sinister demonstration of Morgoth's dark powers.

In this month's Character of the Month biography, @hhimring explores the character of Amlach. Seemingly a minor character (he is mentioned just four times in the published Silmarillion), his story is not only intriguing in its own right but invites speculation about the political relationships between the various houses of the Edain and the different groups of Elves they would encounter upon their migration to Beleriand.

You can read Himring's biography of Amlach here.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 4. Environment

What about global environmental problems, like climate change?

Anarchists do not yet have experience dealing with global problems because our successes so far have only been local and temporary. Stateless, anarchic societies once covered the world, but this was long before the existence of global environmental problems like those created by capitalism. Today, members of many of these indigenous societies are at the forefront of global resistance to the ecological destruction caused by governments and corporations.

Anarchists also coordinate resistance globally. They organize international protests against major polluters and their state backers, such as the mobilizations during the G8 summits that have convened hundreds of thousands of people from dozens of countries to demonstrate against the states most responsible for global warming and other problems. In response to the global activity of transnational corporations, ecologically-minded anarchists share information globally. In this manner, activists around the world can coordinate simultaneous actions against corporations, targeting a polluting factory or mine on one continent, retail stores on another continent, and an international headquarters or shareholders’ meeting on another continent.

For example, major protests, boycotts, and acts of sabotage against Shell Oil were coordinated among people in Nigeria, Europe, and the North America throughout the 1980s and ’90s. In 1986, autonomists in Denmark carried out multiple simultaneous fire bombings of Shell stations across the country during a worldwide boycott to punish Shell for supporting the government responsible for apartheid in South Africa. In the Netherlands, the clandestine anti-authoritarian group RARA (Revolutionary Anti-Racist Action) carried out a campaign of nonlethal bombings against Shell Oil, playing a crucial role in forcing Shell to pull out of South Africa. In 1995, when Shell wanted to dump an old oil rig in the North Sea, it was forced to abandon its plans by protests in Denmark and the UK, an occupation of the oil rig by Greenpeace activists, and a fire bombing and a shooting attack against Shell stations in two different cities in Germany as well as a boycott that lowered sales by ten percent in that country.[67] Efforts such as these prefigure the decentralized global networks that could protect the environment in an anarchist future. If we succeed in abolishing capitalism and the state, we will have removed the greatest systemic ravagers of the environment as well as the structural barriers that currently impede popular action in defense of nature.

There are historical examples of stateless societies responding to large scale, collective environmental problems through decentralized networks. Though the problems were not global, the relative distances they faced — with information traveling at a pedestrian’s pace — were perhaps greater than the distances that mark today’s world, in which people can communicate instantaneously even if they live on opposite sides of the planet.

Tonga is a Pacific archipelago settled by Polynesian peoples. Before colonization, it had a centralized political system with a hereditary leader, but the system was far less centralized than a state, and the leader’s coercive powers were limited. For 3,200 years, the people of Tonga were able to maintain sustainable practices over an archipelago of 288 square miles with tens of thousands of inhabitants.[68] There was no communications technology, so information travelled slowly. Tonga is too large for a single farmer to have knowledge of all the islands or even all of any of its large islands. The leader was traditionally able to guide and ensure sustainable practices not through recourse to force, but because he had access to information from the entire territory, just as a federation or general assembly would if the islanders organized themselves in that way. It was up to the individuals who made up the society to implement particular practices and support the idea of sustainability.

The fact that a large population can protect the environment in a diffuse or decentralized manner, without leadership, is amply demonstrated by the aforementioned New Guinea highlanders. Agriculture usually leads to deforestation as land is cleared for fields, and deforestation can kill the soil. Many societies respond by clearing more land to compensate for lower soil productivity, thus aggravating the problem. Numerous civilizations have collapsed because they destroyed their soil through deforestation. The danger of soil erosion is accentuated in mountainous terrain, such as the New Guinea highlands, where heavy rains can wash away denuded soil en masse. A more intelligent practice, which the farmers in New Guinea perfected, is silvaculture: integrating trees with the other crops, combining orchard, field, and forest to protect the soil and create symbiotic chemical cycles between the various cultivated plants.

The people of the highlands developed special anti-erosion techniques to keep from losing the soil of their steep mountain valleys. Any particular farmer might have gained a quick advantage by taking shortcuts that would eventually cause erosion and rob future generations of healthy soil, yet sustainable techniques were used universally at the time of colonization. Anti-erosion techniques were spread and reinforced using exclusively collective and decentralized means. The highlanders did not need experts to come up with these environmental and gardening technologies and they did not need bureaucrats to ensure that everyone was using them. Instead, they relied on a culture that valued experimentation, individual freedom, social responsibility, collective stewardship of the land, and free communication. Effective innovations developed in one area spread quickly and freely from valley to valley. Lacking telephones, radio, or internet, and separated by steep mountains, each valley community was like a country unto itself. Hundreds of languages are spoken within the New Guinea highlands, changing from one community to the next. Within this miniature world, no one community could make sure that other communities were not destroying their environment — yet their decentralized approach to protecting the environment worked. Over thousands of years, they protected their soil and supported a population of millions of people living at such a high population density that the first Europeans to fly overhead saw a country they likened to the Netherlands.

Water management in that lowland northern country in the 12th and 13th centuries provides another example of bottom-up solutions to environmental problems. Since much of the Netherlands is below sea level and nearly all of it is in danger of flooding, farmers had to work constantly to maintain and improve the water management system. The protections against flooding were a common infrastructure that benefited everybody, yet they also required everyone to invest in the good of the collective to maintain them: an individual farmer stood to gain by shirking water management duties, but the entire society would lose if there were a flood. This example is especially significant because Dutch society lacked the anarchistic values common in indigenous societies. The area had long been converted to Christianity and indoctrinated in its ecocidal, hierarchical values; for hundreds of years it had been under the control of a state, though the empire had fallen apart and in the 12th and 13th centuries the Netherlands were effectively stateless. Central authority in the form of church officials, feudal lords, and guilds remained strong in Holland and Zeeland, where capitalism would eventually originate, but in northern regions such as Friesland society was largely decentralized and horizontal.

At that time, contact between towns dozens of miles apart — several days’ travel — could be more challenging than global communication in the present day. Despite this difficulty, farming communities, towns, and villages managed to build and maintain extensive infrastructure to reclaim land from the sea and protect against flooding amid fluctuating sea levels. Neighborhood councils, by organizing cooperative work bands or dividing duties between communities, built and maintained the dykes, canals, sluices, and drainage systems necessary to protect the entire society; it was “a joint approach from the bottom-up, from the local communities, that found their protection through organizing themselves in such a way.”[69] Spontaneous horizontal organizing even played a major role in the feudal areas such as Holland and Zeeland, and it is doubtful that the weak authorities who did exist in those parts could have managed the necessary water works by themselves, given their limited power. Though the authorities always take credit for the creativity of the masses, spontaneous self-organization persists even in the shadow of the state.

#environmentalism#environment#solarpunk#anti colonialism#anarchism#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#anarchy#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy#economics#climate change#anarchy works

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

One of the main principles of anarchism is Means-End unity.

Put simply, Means-End Unity is the concept that the world we want to make can only be made by living to the values of that world.

If you want a world of kindness, you must be kind.

If you want a world where everything is held in common, you must hold things in common.

If you want a world where every need is met, you must meet every need that you can, including your own.

This is in direct opposition to the “revolutionary procrastination” of other forms of leftism. The anarchist doesn’t wait for the mythical day of liberation, the anarchist liberates daily.

The only way to make the world we want come into being is for us to birth it ourselves, every single day, in every action we take.

Don’t wait. Start now. Maximize help. Reduce harm. Maximize joy.

Live within your values. If you can’t figure out how, then your values need more complexity and more information

#text post#anarchism#wisdom#prefigurative politics#socialism#anarcho disability#means end unity#anarchy#religious anarchism

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

One thing that I think will be important in any social movement is creating spaces for new people to join the communities for a variety of reasons. It can be as simple as wanting to be a part of the movement. Could also be due to them not having anywhere to go. We need to account for the future ahead as much as we can in our prefiguration.

#prefigurative politics#social revolution#climate solutions#climate change#climate action#working class#climate crisis#climate collapse#climate news#climate migration#climate migrants

0 notes

Text

Honestly I think if one thing could help solarpunk the most to become a cohesive movement where we all truly collaborate and look after one another, I think it would be if we stopped generalising.

Not all solarpunk art has to be art nouveau! Not all architecture has to be white stone and green glass in a western-style city! Not everyone is abled enough to just make by hand all the things they want or need that they currently purchase under the capitalist economy. Not everyone you meet on the internet is American (seriously guys, what’s with this assumption, I get it all the time even though I tell you I’m British in my bio). Not everyone wants to work the land or build turbines for a living.

A truly Solarpunk future is one where we speak different languages, employ a variety of techniques to work the land, provide for our material and spiritual needs and restore the environment. It’s open borders and community solidarity and sex worker justice and indigenous sovereignty. For some people it looks like a quiet rural life and for others it’s all about the bustle of a city full of reliable transit and accessible third spaces. It’s also about realism. Some things will be rarer because we will have had to massively slow down trade and shipping to decarbonise it - we’ll need to eat locally as much as possible. In utopia some disabled people will still need cars, so we need EVs despite their current imperfections.

There will likely be mosques, community centres, food forests, art galleries and hospitals. People will be trying their best. We’ll mess up. We can’t predict what will happen and we certainly can’t universalise one experience. And if Solarpunk is all about living out a prefigurative politics where you imagine you exist in a world already free, then it’s essential we try to practice that open-mindedness and lack of assumptions in our day to day interactions, in real life and on the internet

480 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Around the mid-2000s I began noticing a very distinct change in Daniele’s attitude. He was feeling increasingly alienated from Israeli society as it was evolving and mentioned a couple of friends that he no longer talked to. While he continued to be invested in Israel, he nonetheless found it hard to justify why he was. He adopted a kind of ‘I don’t like what they are doing but we Jews don’t have much choice but to support Israel’. On one occasion, I told him a story related by Edward Said. I can no longer find the reference so I might have changed the story a bit. I think it was about an intellectual who was a reluctant Zionist, but that Said liked and respected, nonetheless. In explaining why he supported Zionism despite not having any affinities with it, this intellectual said something like this: if your son steals all your money and bets it on a horse, you might not like what you son has done and you might not even like the horse, but would you want the horse to lose the race? Daniele really liked that story. He thanked me for it and said it really captured how he felt.

In 2014, however, two years before he died, Daniele surprised me. We happened to be visiting him and his wife in Rome, in the midst of what became known as ‘Operation Protective Edge.’ This operation, in many ways, prefigured the 2023 Israeli invasion of Gaza in its exterminatory deadliness, and its indifference to civilian life. Daniele was upset by it. As we were watching the violence unfurl on the news, he got particularly agitated watching a clip of two Israeli soldiers leading away a handcuffed young boy. He sighed heavily, and turned to me and said: ‘I no longer care if this horse wins anymore. It’s like, as they say in English, “flogging a dead horse”.’ I did not dare say anything triumphant as it would have cheapened the moment, and disrespected what he must have experienced saying this.

It was an important moment to me. As I noted above, while I always considered the linking of the Holocaust and Israel’s right to exist as an ethno-national entity intellectually untenable, I nonetheless understood the people who have been traumatised by the Holocaust and who experienced the relation between it and Israel as sacrosanct. I always refrained from engaging with such people critically. That moment when Daniele referred to Israel as a ‘dead horse’ helped me break the aura of sanctity that surrounded the nexus between the Holocaust and Israel. After all what has happened and has been happening, I increasingly see in the people highlighting this nexus as self-serving ideologues whose collapsing of the idea of ‘being at home in the world’ with the idea of ‘defending an ethno-national state’ is both politically and ethically untenable."

- Ghassan Hage, The Metamorphosis of Daniele the Zionist

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

apropos of @txttletale im thinking about how my approach toward masking is more or less the same as my approach to veganism, that is, that engagement in these practices is a prefigurative politic that helps me in demanding collective action — eg requiring students to mask in my classrooms/at conference panels, and ensuring wide availability of healthy, safe, unexpired and allergen friendly vegan food when I am distributing food. These individual actions aren’t enough alone to effect transformative change, but they in and of themselves function as moments of education and edification for me and others, demonstrating what can be possible and reaffirming the need to demand better of the social structures we make our lives around

as in, these projects aren’t accessories to individual ideology but insistences that we won’t lay down and give up in the face of violence + greed + abandonment

#again I think one of the most valuable things abt this work is as an educational tool#bc no transformation happens w/o educating ourselves about how we live now and how we could be living#mine#I don’t know if this makes sense but I’m making a lot of connections in my head#it is important to live my ideals regardless of the scale at which they are implemented at s given time#I believe in living as if they are possible because that keeps me alive

28 notes

·

View notes