#reflectionsonhealing

Photo

In ancient Egypt, what we call medicine was understood as a form of magic. Practicing medicinal magic honored the goddess Sakhmet, the ferocious, lion-headed protector of Egypt. Though she is often thought of as protecting Egypt from invasion, this life-size sculpture of the goddess was one of hundreds commissioned by king Amunhotep III for his funerary complex, which scholars believe were meant to thank the goddess for the ending of a plague that ravaged the region. Sakhmet was believed to be so ferocious that if her wrath was not calmed after the enemy was defeated, she may bring about the end of the world. She could be placated with offerings of beer dyed red to resemble blood as well as the flooded Nile carrying silt, suggesting renewal and rebirth.

Like today, preventing disease was the first course of action. The ancient Egyptians turned to apotropaic deities who were believed to be able to scare-off the evil and chaotic forces, including those that caused disease. A magical knife, adorned with the head of a protective leopard, and fearsome, hybrid gods—lion-headed Aha showing domination over poisonous snakes, and hippo-based Tawaret wielding a knife herself—would cut the heads off of demons. Over time, gods like Aha, and the similar Bes, were ascribed more and more traits to address more and more concerns. This seven-headed figure with four sets of wings, the tail of a falcon and a crocodile, the heads of jackals for feet, and enveloped in a ring of fire is an example of a deity so mysterious and powerful that it could guard against a variety of maladies described on this small papyrus scroll meant to be rolled up and carried around.

In the final weeks of 2020, we're taking time to find comfort, hope, and healing with artworks in the Museum's collection.

Egyptian, Bust of the Goddess Sakhmet, ca. 1390-1352 B.C.E. Granodiorite. Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Dr. and Mrs. W. Benson Harer, Jr. in honor of Richard Fazzini and the excavations of the Temple of Mut in South Karnak, Mary Smith Dorward Fund and Charles Edwin Wilbour Fund, 1991.311. → Egyptian, Fragment of "Magic Knife," ca. 1759-after 1630 B.C.E. Frit. Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Evangeline Wilbour Blashfield, Theodora Wilbour, and Victor Wilbour honoring the wishes of their mother, Charlotte Beebe Wilbour, as a memorial to their father, Charles Edwin Wilbour, 16.580.145. → Egyptian, Scene from a Magical Papyrus, 664-525 B.C.E. Papyrus, ink. Brooklyn Museum, Bequest of Theodora Wilbour from the collection of her father, Charles Edwin Wilbour, 47.218.156a-d.

#reflectionsonhealing#bkmegyptianart#egyptian art#egyptian#sakhmet#healing#magic#medicin#goddess#lion#protector#plague#renewel#rebirth#disease#prevention

599 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In "Leaves of Grass" the poet Walt Whitman writes, "Happiness is not in another place, but in this place, not for another hour, but this hour." Finding peace in the present, as well as the constant passage of time, are themes in this work by Tiffany Studios, in which unique glass-making techniques are used to evoke the atmosphere of dawn and dusk in a tranquil forest. Although fixed in stained glass, the scenes appear to shift depending on the light and time of day, with complex coloring and layers that give a sense of depth. The transition of seasons from spring to autumn is a reminder that change is continual.

In the final weeks of 2020, we're taking time to find comfort, hope, and healing with artworks in the Museum's collection.

Posted by Forrest Pelsue

Tiffany Studios (1902-1932). Dawn in the Woods in Springtime and Sunset in Autumn Woods, 1905. Stained glass window. Brooklyn Museum, Gift of All Souls Bethlehem Church, 2014.17.1. Creative Commons-BY

#reflectionsonhealing#Tiffany#Tiffany Studios#stained glass#transition#season#change#contiual#walt whitman#leaves of grass#happiness#place#peace#present#dawn#dusk#tranquility#bkmdecarts

132 notes

·

View notes

Photo

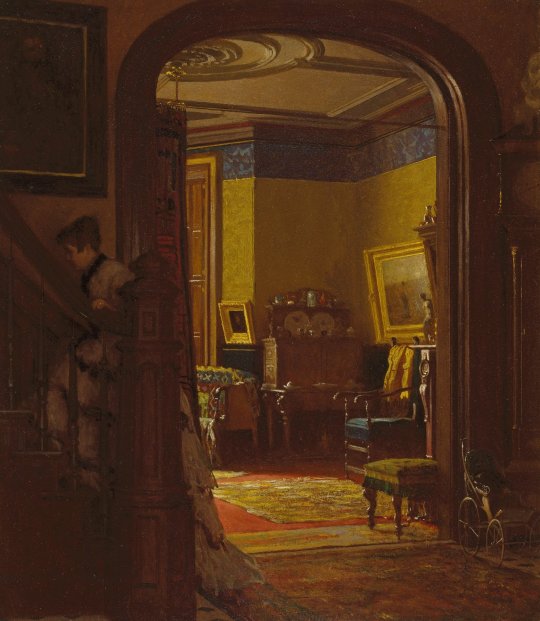

This painting’s title, Not At Home, may seem strange, since there is clearly someone on the stairs. In the past, however, this phrase indicated that the occupants of the house were not available to receive visitors. The painting held a particularly personal meaning for the artist, Eastman Johnson: the woman on the stairs is his wife, Elizabeth, on her way to the more private areas of their residence on Manhattan’s West Fifty-fifth Street. While the holidays can bring a schedule full of friends and family, it’s also important to appreciate—especially this year—the intimate spaces where we can rest, relax, and be “not at home.”

In the final weeks of 2020, we're taking time to find comfort, hope, and healing with artworks in the Museum's collection.

Posted by Forrest Pelsue

Eastman Johnson (American, 1824-1906). Not at Home, ca. 1873. Oil on laminated paperboard. Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Gwendolyn O. L. Conkling, 40.60

120 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In Karon Davis’s nearly life-sized sculpture “Nicotine,” a tired yet resolute nurse sits alone, savoring a cigarette break. The nurse’s colorful scrubs take shape around an armature of plaster, and frayed edges reveal shredded medical bills amassed from cancer treatments for the artist’s late husband, painter Noah Davis. Begun in collaboration, “Nicotine” was completed by Karon following Noah’s death, and their harrowing, expensive hospital stay. A 2016 rumination on incalculable personal loss, the work also emphasizes how care and humanity persist, despite the impersonal bureaucracy of the U.S. healthcare system, also highlighting the role of Black women in the field in particular. Viewed in 2020 amidst a devastating pandemic, “Nicotine” reminds us of the emotional and physical toll that healthcare workers endure for the sake of the health of their patients and communities.

In the final weeks of 2020, we're taking time to find comfort, hope, and healing with artworks in the Museum's collection.

Posted by Carmen Hermo

Karon Davis. Nicotine, 2016. Plaster, cloth, oil paint, synthetic hair, clothing, wire, shredded bills, coffee cup, wood, mirror, cigarette. Brooklyn Museum, Purchase gift of Beth Rudin DeWoody, 2018.2. © artist or artist's estate (Photo: Photo courtesy Wilding Cran Gallery)

#Karon Davis#reflectionsonhealing#brooklyn museum#comfort#hope#healing#healthcare workers#health#patients#communities#emotional#physical#pandemic#hospital

101 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Multiple notions of healing coincided in the Spanish Americas—a crossroads of diverse Indigenous, European, African, and Asian cultures. This eighteenth-century painting depicting the devotional figure of Our Lady of Cocharcas centers the Catholic traditions imported to the Americas by Spanish missionaries. The statue is believed to have been brought to the highlands of present-day Peru by Sebastián Quimchi, a young Indigenous convert, after he was miraculously healed of his physical ailments during a pilgrimage to another Marian statue along Lake Titicaca.

Our Lady of Cocharcas is seen here as part of a procession in which Indigenous, African, and criollo (Spanish descent) devotees flock to the Marian statue, seeking blessings and miracles. The conical, mountainlike shape of the Virgin’s floral dress creates a deliberate association with Pachamama, the Andean earth-mother goddess, speaking to survival, transformation, and appropriation of Indigenous beliefs during the colonial period.

In the final weeks of 2020, we're taking time to find comfort, hope, and healing with artworks in the Museum's collection. #reflectionsonhealing

Posted by Joseph Shaikewitz

Cuzco School artist, Our Lady of Cocharcas Under the Baldachin, 1765. Oil on canvas,. Brooklyn Museum, Bequest of Mary T. Cockcroft, by exchange, 57.144

#reflectionsonhealing#cuzco school#peru art#our lady of cocharcas#spanish americas#healing#indigenous#catholic#traditions#spanish missionaries#Sebastián Quimchi#lake titicaca#criollo#marian#spanish#floral dress#pachamama#andean#earth-mother#goddess#survival#transformation#colonial period

54 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In this illustration, Winslow Homer noted a custom that was familiar to many Americans of the time: the New Year’s Day social call. Every January 1st, households would receive guests for short visits; typically, women would dress up and remain home as hostesses, while men went out to make the rounds of their social circles. Through this tradition, which was observed from the Dutch colonial era of the 1600s through the Gilded Age of late 1800s, many people celebrated this day as an opportunity to renew bonds with friends and family, share good wishes for the year ahead, and enjoy food and drink together.

2020 has significantly changed the ways we gather and observe important dates. Despite the challenges of our current circumstances, we’ve still found ways to connect, from video chats to socially distanced outdoor dining. How can we continue to sustain our own ties with family, friends, and neighbors? What new rituals might we create to carry us forward into 2021?

In the final weeks of 2020, we're taking time to find comfort, hope, and healing with artworks in the Museum's collection.

Winslow Homer (American, 1836-1910). Waiting for Calls on New-Year's Day, 1869. Wood engraving. Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Harvey Isbitts, 1998.105.122

#ReflectionsonHealing#Winslow Homer#New Year#New Year's Day#art#illustration#social calls#brooklyn museum#2020#2021

44 notes

·

View notes