#triploid

Text

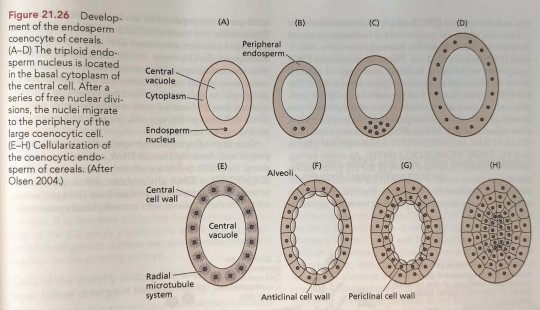

During cereal endosperm development, the triploid primary endosperm nucleus undergoes a series of mitotic divisions without cytokinesis, and the nuclei migrate to the periphery of the central cell, which also contains a large central vacuole (Figure 21.26, see parts A-D). As in the Arabidopsis coenocyte, each of nuclei is surrounded by radially arranged microtubules (see Figure 21.26E). Anticlinal walls form initially between adjacent nuclei, resulting in the tubelike alveolar cells, with the open end pointing toward the central vacuole (see Figure 21.26F). (...) The innermost layer of daughter cells remains alveolar in structure, and continues to divide periclinally until cellularization is complete (see Figure 21.26G and H). The most important source of starchy endosperm cells is the interior cells of the cell files that are present at the completion of endosperm cellularization (see Figure 21.26H).

"Plant Physiology and Development" int'l 6e - Taiz, L., Zeiger, E., Møller, I.M., Murphy, A.

#book quotes#plant physiology and development#nonfiction#textbook#triploid#endosperm#mitosis#cell division#cell differentiation#plant cells#cytokinesis#vacuole#arabidopsis#coenocyte#microtubule#anticlinal#alveoli#daughter cells

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

🧬 Check out the next big thing in the cannabis breeding world—triploid genetics!

😁 These unique weed plants show great potential, such as higher yields, faster flowering, and enhanced profiles.

🌱 Read my guide to see 3 new triploid strains on the market, available in feminized seeds.

🔗 https://medium.com/@moldresistant/triploid-cannabis-explained-is-it-worth-growing-6fde38cda5d3

#triploid#cannabis#weed#triploid cannabis#triploid buds#marijuana#marijuana seeds#sativa#thc#cbd#indica#ganja#stoners#cannabis culture#blaze it#weed seeds#pot#strains#cannabis strains#marijuana strains#weed strains#medical marijuana#cannabis seeds#cannabis plant#weed plant#weed plants

0 notes

Text

shemale big dick Chanel Santini, Natalie Mars

Kyle Mason painted Horny Teens Alice, Jessica and Jewels faces with his hot cum

Just me fucking my ex outside

Cum on clothes handjob

Alexis texas en cuatro en tanga

Eva Latex pov blowjob deep minet big dick mask pink leggins high heels fetish milf gonzo mature home

Skater bondage teen gay and man asphyxia porn xxx Wanked To

Blind Japanese girl suck a dick and got cum shot in her face

PervCity Asa Akira Brooklynn Lee and London Keyes Oral Overdose

Teengirl pisst auf Dildo und dann fickt ihre Fotze

#bowsaw#Bilskirnir#well-impressed#building#sovkhoz#Sakais#igniters#Kuroshio#gallach#havioured#triploids#reeveship#sculpts#cityscapes#gouter#chucking#ultracentrifuging#protevangelium#symphogenous#Massalia

0 notes

Text

射干|著莪[Shaga]

Iris japonica

Even though Sakura had not yet bloomed, I saw Shaga blooming in the shade of a forest, so took some pictures of them. Its flowering season is usually from April to May.

Well, sometimes I head for some mountains far from my home in search of rare flowers.

Late spring a couple of years ago, on a motorcycle, I took a side road off the street and passed the last lonely village in the bosom of a mountain, as if aiming for the top, went deeper and deeper along the narrow path for a while, and then, found a lot of flowers of Shaga in a flat and somewhat open area at a foot of a dense forest. I took off the helmet and looked at them.

Standing there, all I can hear is the chirping of birds, the murmur of the mountain torrent, and the sound of the wind rustling leaves through the trees. I imagined what was the scene like when it first bloomed here.

Although Shaga has the specific name of japonica, it is native to China and was introduced in the distant past. Those in Japan have triploid chromosomes, which means that they do not produce seeds and do not distribute themselves more and more naturally. In other words, it is highly likely that someone planted them this place.

I do not know when it happened or who they were, but I was moved to think that there would have been human life in such a lonely, deep mountain in the middle of nowhere.

Nearby, the flowers of Yamabuki were in bloom.

Shaga also has another name, 胡蝶花[Kochōka](Buttefly flower.)

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kordofan melons from Sudan are the closest relatives and may be progenitors of modern, cultivated watermelons. Wild watermelon seeds were found in Uan Muhuggiag, a prehistoric site in Libya that dates to approximately 3500 BC. Watermelons were domesticated in north-east Africa, and cultivated in Egypt by 2000 BC, although they were not the sweet modern variety. Sweet dessert watermelons spread across the Mediterranean world during Roman times.

Many 5000-year-old wild watermelon seeds (C. lanatus) were discovered at Uan Muhuggiag, a prehistoric archaeological site located in southwestern Libya. This archaeobotanical discovery may support the possibility that the plant was more widely distributed in the past.

In the 7th century, watermelons were being cultivated in India, and by the 10th century had reached China. The Moors introduced the fruit into the Iberian Peninsula, and there is evidence of it being cultivated in Córdoba in 961 and also in Seville in 1158. It spread northwards through southern Europe, perhaps limited in its advance by summer temperatures being insufficient for good yields. The fruit had begun appearing in European herbals by 1600, and was widely planted in Europe in the 17th century as a minor garden crop.

Early watermelons were not sweet, but bitter, with yellowish-white flesh. They were also difficult to open. Through breeding, watermelons later tasted better and were easier to open.

European colonists and enslaved people from Africa introduced the watermelon to the New World. Spanish settlers were growing it in Florida in 1576. It was being grown in Massachusetts by 1629, and by 1650 was being cultivated in Peru, Brazil and Panama. Around the same time, Native Americans were cultivating the crop in the Mississippi valley and Florida. Watermelons were rapidly accepted in Hawaii and other Pacific islands when they were introduced there by explorers such as Captain James Cook. In the Civil War era United States, watermelons were commonly grown by free African people and became one symbol for the abolition of slavery. After the Civil War, African people were maligned for their association with watermelon. The sentiment evolved into a racist stereotype where Africn people shared a supposed voracious appetite for watermelon, a fruit long correlated with laziness and uncleanliness.

Seedless watermelons were initially developed in 1939 by Japanese scientists who were able to create seedless triploid hybrids which remained rare initially because they did not have sufficient disease resistance. Seedless watermelons became more popular in the 21st century, rising to nearly 85% of total watermelon sales in the United States in 2014

A melon from the Kordofan region of Sudan – the kordofan melon – may be the progenitor of the modern, domesticated watermelon. The kordofan melon shares with the domestic watermelon loss of the bitterness gene, while maintaining a sweet taste, unlike other wild African varieties from other regions, indicating a common origin, possibly cultivated in the Nile Valley by 4360 BP (before present)

#kemetic dreams#watermelon#wow#kordofan#sudan#ta seti#nubia#progenitor#nile valley#african#afrakan#africans#libya#north africa#african culture#north ifriqiya#ifriqiya#kordofan melon

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

American Toad: These toads lay up to 8000 eggs in a single clutch, laid out in a string. Tadpoles have been proposed to have a mutually beneficial relationship with the algae Chlorogonium, where the algae growing on their backs seems to cause them to grow faster. Like most toads, their parotoid glands contain bufotoxin, a foul-tasting chemical. They are also known to interbreed with A. woodhousii and A. hemiophrys in regions where their ranges overlap. Females of the same clutch, however, are able to recognize their brothers through their calls, avoiding potential inbreeding.

Edible Frog: Found throughout Europe, this species is a hybrid of Rana ridibundus (the marsh frog) and R. lessonae (the pool frog). Due to this, they can be either diploid or triploid and demonstrate different genomes due to a process called hybridogenesis. They are also sometimes quite difficult to distinguish from either parent species, taking on traits from one or both. For example, their hibernation behaviours vary depending on which parent species they coexist with: if near R. ridibundus, they hibernate in water. If near R. lessonae, they hibernate on land. As their common name suggests, they were often eaten by humans of the area.

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

Cavendish Bananas, due to being triploid, are unable to produce seeds, and are instead propagated with identical clones. Do with this information what you will.

. "Wow! What a messed up fact! It's a good thing us most of us fruit and veggie toons aren't meant to be based on highly scientifically-specific species of real-world foods and probably don't follow most of the same rules and logic one-to-one to begin with."

#((He's got nephews with different personalities. They're not even triplets. I don't think DB and his fam are any specific type of bananas))#anonymous#ask#appeeling show host (dancing banana)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

PROJECT LUCID | LIMINA

GENERA//////////////////////////////////////////////////

Astro-signatures (ןוاiا)

ן ו ا i ا

The characters composing the signatures are Semitic and Latin characters translatable to the names of the planets they represent.

Each vertical bar in a signature indicates a planetary body orbiting the star.

The length of the vertical bar indicates the relative length of that planet’s solar year.

“i” indicates a habitable planet in that elliptical ring corresponding to it’s displacement from the right.

E.g. Иawaia’s signature (ןוاiا) indicates a habitable planet second from the solar center.

SOPHIA///////////////////////////////////////////////////

ΩΔiلاбe | John 12:25

FEDERA///////////////////////////////////////////////////

ןוاiا | Иawaia (a Crvena-Seren, or a red supergiant star, Иawaia hosts one inhabitable planet: Ayatha.)

יוןוי | Yunoy (home to a relaxing paradisal retreat, a terraformed möbius superstructure orbits the tectonically active planet Orestes, harnessing its thermal energy. All manner of outdoor activities from hiking to kayaking, swimming, fishing, camping, etc. Best kept secret this side of Abrium.)

ןויון | Nuyon

ןוاוי | Nevi (at least one planet with nitrogen-rich atmosphere, evidence of intelligent life; terraforming efforts.)

liיוןו | Liiono (one occupied planet hosts lithium mines)

יוןاi | Iona

ןיןוי | Ni Nui

LENGUA///////////////////////////////////////////////

Abrium - Hebrew

Agreda - Greek

APPLICA/////////////////////////////////////////////

•: وةا | log is a real-time quasi-quantum linguistic extrapolation auxiliary device. Log’s signature triploid (•:) appears to indicate the program is active.

م ن ة ي | Spatial Orbital Units Projector (SOUP) displays solar system orbits.

م م ن | Utility•Polyglot •pH quantum and chromatic radiometer. Combines numerals, historic context and religious concordance to aid in decision making. Measures the catalytic capacity and potential for linguistic intimation of information providing lucrative and insightful mooring lines. The name itself is an example of the concept. Borrowing from the name of the city Uppsala, Sweden. The omitted portion of the name s-a-l-a, spells, in Spanish, "living room." The application’s aim is to facilitate comfortable conversation about lofty ideas by phasing through linguistic and academic barriers without disrupting one’s fabric of reality.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I could genuinely cry like IT WORKED!!!! Months of work and I successfully did something big!!!!!!! I actually made triploid yeast!!!!!!!!!!

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

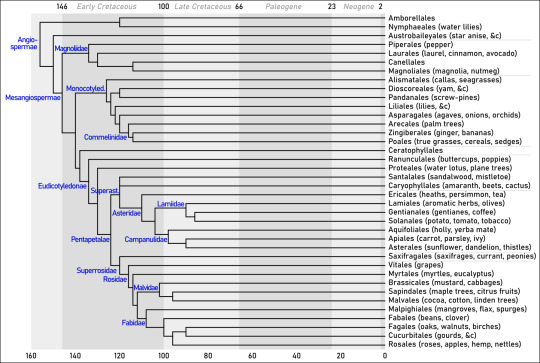

Tree of Life 4: Angiospermae (flower plants)

[Disclaimer: taxonomy is a complex, ever-changing field, and this overview is certainly not going to be exhaustive, especially concerning extinct groups]

← Part 3 (Archaeplastida: green plants)

Part 5 (Unikonta: amoebae, fungi, and such) →

Angiospermae “vessel seeds”: The clade including all plants that produce flowers and fruits. The name refers to the fact that ovules (the female gametophytes, see part 3) are enveloped in structures carpels, which are accessed through a pistil. The pistil may be surrounded by the stamina (sing. stamen), the male structures that produce pollen grains (which are the male gametophytes). In some species, male and female structures coexist in the same flowers; in other, they are found in different flowers of the same plant; in yet others, only on different plants. Finally, these structures are surrounded by the perianth, concentric whorls of modified leaves that are commonly called petals (for botanicists, petals are only a subset of the perianth). The entire structure makes up a flower.

Pollen granules, falling upon it, produce tubes that enter the pistil and release non-flagellate sperm cells right next to the ovules. Upon fertilization, each ovule develops into a seed: each contains an egg cell that will become the embryo, the part of the seed destined to sprout into the daughter plant. At the same time, other sperm cells fertilize the egg’s companion cells, which develop into the endosperm, the seed’s “pulp” or nutrient reserve, usually mostly starch. (The endosperm is triploid, which means it has three copies of each chromosome.) The fact that the formation endosperm requires fertilization ensures that it is never wasted on an un-fertilized egg. The lower carpel matures into the fruit surrounding the seed, while the rest of the flower withers away.

Flower plants arose somewhen between the very end of the Jurassic and the earliest Cretaceous, some 150 to 140 Ma (million years ago), quite late for plant evolution, and went through an explosion of diversity in the early Cretaceous. (An early form of the ovule coating leading to fruits is found in † Caytonia, a seed fern (see part 3) from the Jurassic.)

By 100 Ma, most of the orders we recognize today were in place, and flower plants had replaced Gymnosperms as the main component of worldwide flora. This explosion was probably driven by co-evolution with pollinating insects (at first beetles and scorpionflies, then early bees and butterflies), which carried pollen from a flower to another in exchange for sugar-rich nectar. Flowers evolved large and colorful perianths as signals for these insects. Later, many sub-groups of Angiosperms gave up on insects and entrusted their pollen to wind or water, like their pre-flower ancestors.

Let’s go into detail below the cut. As per botanical tradition, plant orders are named after a representative genus: for example, Vitis (the common grape) → Vitales. Note that because of the way plants grow (by elongating and branching at the end of their stems), they tend to take irregular fractal shape that vary even between individuals. Their body is not organized in systems like that of animals, but rather it’s composed of small modular elements that are highly variable; therefore, clades of plants often cannot be identified by obvious morphological features -- "trees”, for example, evolved independently from herbs dozens of times.

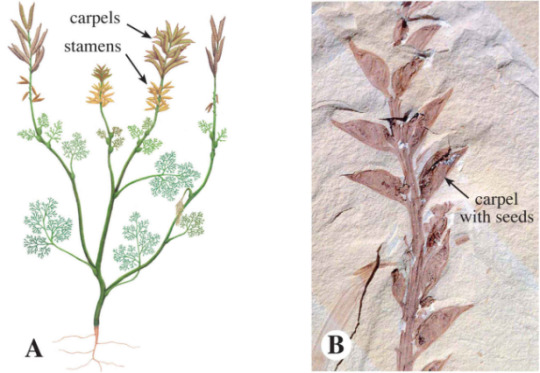

The earliest fossil plant acknowledged as an Angiosperm is † Archaefructus, from Early Cretaceous China (about 125 Ma): it was a small semi-aquatic shrub which had carpels and stamina arranged along branches, rather than condensed in a flower, and no perianth. Combined with the aquatic nature of Nymphaeales and Ceratophyllales, this suggests that flower plants first evolved in aquatic environments, and spread their pollen with water.

Reconstruction and fossil of † Archaefructus, possibly the “uncle” of all flower plants. (Simpson 2019)

1. Amborellales: Actually only one species, Amborella trichopoda from the jungles of New Caledonia; the most basal of all Angiospermae. A small shrub with almond-shaped leaves, it has rough-looking flowers with white proto-petals and green carpels, still very clearly modified clusters of leaves. Unlike all other flower plants, the carpels are clearly separated from each other.

2. Nymphaeales: A clade of aquatic plants sprouting from buried rhizomes, with disk-shaped floating leaves and flowers emerging from the water on stiff, vertical stems. Water lilies (e.g. Nymphaea, the giant Victoria from the Amazon basin) are here.

3. Austrobaileyales: Tropical trees and shrubs whose leaves contain aromatic oils. The flower perianth is a compact cup whose carpels form peculiar star-shaped fruits: for example, the star anise (Illicium verum), which is used as spice in dried form.

4. Mesangiospermae: The group that contains all Angiosperms except for the three basal orders we just saw. Here a new type of water vessel appears, formed by short and wide hollow cells with sieve-like plates at both ends. They might be more efficient at carrying dissolved salts and sugars than the old tapering, pitted conductive cells; however, they're more likely to be clogged by gas bubbles at lower temperatures, which might be the reason sub-polar forests are still dominated by conifers.

4a. Magnoliidae: An ancient group put together on molecular basis.

4a1. Piperales: This order contains the ornamental Aristolochia, with a hanging red three-petaled flower. More importantly, here is Piper nigrum, whose small fruits grow clustered on a vertical spike, and give us red, black, and white pepper (ripe fruit, unripe dried, and bare seed, respectively). Right next to it, kava (Piper methysticum), whose dried root is consumed as a narcotic in Polynesia.

4a2. Laurales: Another order of tropical trees and shrubs producing aromatic oils. Accordingly, we find more spices (Cinnamomum verum, cinnamon), herbs (Laurus nobilis, laurel or bayleaf, from which the crowns of Roman poets and generals were also made), and perfumes (Cinnamomum camphora, camphor), as well as the avocado (Persea americana).

4a3. Magnoliales: These plants have large flowers with a pillar-like structure bearing both stamina and carpels. Here we find magnolias (Magnolia) and tulip-trees (Liriodendron tulipifera), whose fruits are pinecone-like aggregates of woody seed-vessels; as well as Myristica fragrans, from which both nutmeg and mace are made (the first from the seed, the second from the gummy red pulp that covers it).

The relatively primitive flower and pinecone-like fruit of Magnolia grandiflora (Magnoliales) from Southeastern USA. (Wikipedia, Ianaré Sévi/Berthold Werner)

4b. Monocotyledonae: One of the big groups of flowering plants, accounting for about a fifth of all their species. The name refers to cotyledons, the proto-leaves that are first to sprout from the embryo before mature leaves are ready, and to the fact that Monocotyledon embryos have only one, rather than two like all other Angiosperms, which were once known as “Dicotyledons”. Monocotyledons, for unknown reasons, also have many small vascular bundles scattered in the stem, as opposed to a single central bundle or a ring; this gave no problem to early grass-like species, but it means that they have very little secondary growth (see part 3) and cannot produce true wood. Accordingly, very few Monocotyledons are trees. These plants can often be recognized by their leaves, since their veins are either parallel, running along the leaf’s length, or sideways in a feather-like pattern from a single central vein.

4b1. Alismatales: At the base of this order we find the family Araceae, whose distinctive trait is a spadix, a fleshy pillar-like structures carrying small flowers on its surface. The spadix is surrounded by a modified leaf that resembles a petal; thus, what you might think is the flower of a calla lily (Zantedeschia aethopica) or a taro (Colocasia esculenta, farmed for its root in Polynesia), is actually a whole complex of flowers or inflorescence, which develops into a pineapple-like compound fruit. One such inflorescence, that of the titan arum Amorphophallus titanum, stands 3 meters tall. At the opposite extreme, the little floating duckweed (Lemna and Wolffia) measure only a few mm. Other members of Alismatales took to the sea: the alga-like seagrasses Zostera and Posidonia, which form vast meadows on the bottom of shallow warm seas, spreading thrugh floating fruits.

An undersea meadow of turtle seagrass (Thalassia testudinum, Alismatales) at the Bahamas. Despite appearences, these are not algae but proper plants with roots, leaves, and flowers (which are very small, since pollen is carried by water). (Wikipedia, James St. John)

4b2. Dioscoreales: The stars of this order are yams (several species of genus Dioscorea), whose starch-rich roots are staple crops in Africa, South Asia, South America, and Oceania. Unlike most Monocotyledons, they have re-evolved back the old reticulated leaf veins. Yams also produce an estrogen-like hormon, diosgenin, that was used for the earliest birth control pills.

4b3. Pandanales: The screw-pines (Pandanus and other genera) are considered the only true Monocotyledon trees, but the inability to produce thick wood forced them into strange shapes. The trunks are thin, twisted, splitting in large clumps, and are propped up at the base by thick roots. Individual flowers are small and sometimes lack petals: the inflorescences are effectively bundles of naked stamina and carpels.

A screw-pine in Hawai’i (Pandanus tectorius, Pandanales). (Wikipedia, Forest & Kim Starr)

4b4. Liliales: The most illustrious family is Liliaceae, distinguished by radially-symmetrical flowers with a single whorl of six petals and six large stamina. Here are true lilies (Lilium) and tulips (Tulipa). They grow from onion-like bulbs. Among other Liliales is the autumn crocus (Colchicum autumnale), whose colchicine, is both a poison and a drug with many medical uses.

4b5. Asparagales: A highly diverse order, which has the honor of including the largest family of Monocotyledons: Orchidaceae, with some 28,000 species. Orchids (whose name is Greek for “testicle”, after the shape of their tubers), with their distinctive bilaterally-symmetrical flowers are here, from Vanilla planifolia, whose seeds give vanilla, to Angraecum sesquipedale, with a 45 cm-long tube that can only be pollinated by a moth with a proboscis of equal length. The windborn seeds of orchids are so small that they carry fungal cells from which they depend for nourishment. The other Asparagales (recognized by black seed coating) include the common asparagus (Asparagus officinalis); the day-lily (Hemerocallis) and the saffron flower (Crocus sativus), whose stamina are dried and ground into the most expensive-by-weight spice in the world; the genus Allium, which encompasses onions, leek, and garlic; the sharp-leaved agaves (Agave) and Joshua tree (Yucca brevifolia) of the American deserts; and the strange Australian “grass trees” (Xanthorrhoea), with meters-long spikes rising from a clump of grass-like leaves; and many, many others.

The bee orchid Ophrys apifera (Asparagales), found in Europe and the Mediterranean region, does not attract its pollinator, a solitary bee, with nectar. Rather it, pretends to be a receptive female bee; when a male bee attempts to mate with the orchid, it will coat itself in pollen to be carried to the next flower. (Wikipedia, Bernard Dupont)

4b6. Commelinidae: A group of Monocotyledon orders, mostly put together by molecular data, but also by the presence of particular fatty acids in their cell walls that happen to glow under UV light.

4b6a. Arecales: Palm “trees”, from coconut palms (Cocos nucifera) to date palms (Phoenix dactylifera) to many others (though some species are herbs or lianas). The trunk is unbranched (except in Hyphaene), mostly formed by the leftover sheath of fallen leaves.

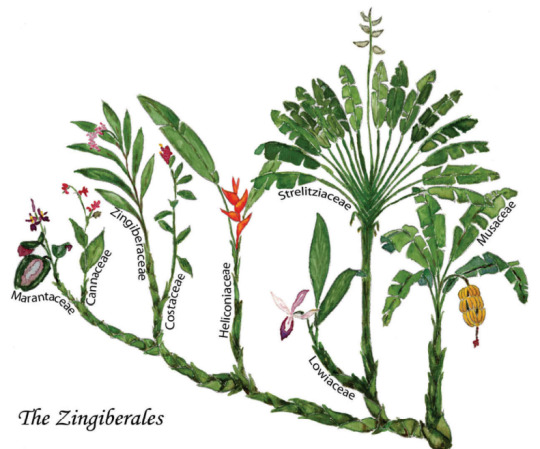

4b6b. Zingiberales: Plants in this mostly tropical order have in common a stem filled with air chambers and leaves whose edges roll around each other. Leaf veins usually have a feather-like structure. One one side of the order we find the banana (Musa paradisiaca), another woodless “quasi-tree”, with large hanging inflorescences that develop into banana bunches. On the other, a variety of spices including ginger (Zingiber officinale), turmeric (Curcuma domestica), and cardamom (Elettaria cardamomum). The order also contains several exotic flowers, such as the bird-like Strelitzia and the flame-like Heliconia.

A pictorial cladogram of the Zingiberales. (Simpson 2019, credited to Ida Lopez)

4b6c. Poales: Here we find all true grasses (Poaceae), which includes not only humble lawn grass (Poa, Festuca, &c), but also all cereals, from wheat (Triticum) to rice (Oryza sativa) and from maize (Zea mays) to sorghum (Sorghum); as well as the sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum). Most are wind-pollinated plants with reduced stems and numerous, tiny flowers, which develop into ears or spikes. Seeds, of course, are very rich in starch-based endosperm. They have a hollow stem, divided in compartments, that manages to grow very tall compared to its width even in absence of true wood, reaching its extreme of course in bamboos (Phyllostachys edulis, which is farmed for wood and edible shoots in China and Japan, can stand 28 m tall). Leaves develop as sheaths surrounding the stem. Another important family of Poales is Bromeliaceae, many of whom are herbs with reduced roots that grow on the branches of tropical trees -- although the one we see most often, the pineapple (Ananas comosus), does not. In other families we find swamp reeds (e.g. Typha), and sedges (such as papyrus, Cyperus papyrus).

An unripe pineapple (Ananas comosus, Poaceae), sole fruit of its plant (actually developed from a whole cluster of flowers, one for each scale) growing in the Hawai’i. (Wikipedia, Diego Delso)

4c. Ceratophyllales “horn-leaves”: Just like the not-closely-related Anthocerotophyta (see part 3), these too are known as “hornworts”. They are a handful of species of small aquatic plants with whorls of leaves growing at regular intervals out of the thin, flexible stem. Flowers are tiny, with fused petals. Ceratophyllum demersum is commonly grown in aquaria.

Slightly older than † Archaefructus, † Montsechia from Early Cretaceous Spain (130 Ma), an aquatic plant with thin stems and paired almond-like fruits, was likely an early member of this order.

4d. Eudicotyledonae: The bulk of modern plant diversity, making up about 75% of all Angiosperm species. They all share tricolpate pollen (or later variants thereof), meaning that each pollen grain opens with three grooves, as opposed to the single-grooved grain ancestral to seed plants.

4d1. Ranunculales: Mostly herbs and shrubs with colorful flowers, most notably poppies (including the opium poppy, Papaver somniferum, from whose fruit morphin and its derivates are extracted) and buttercups (Ranunculus).

4d2. Proteales: Another one of those clades that contains multiple subgroups very unlike each other. Here we have the aquatic lotus (Nelumbo nucifera), whose flowers fuse into the perforated seed capsule that usually pops out when you look up “trypophobia”, and whose waterproof leaves and periodically flowers rising out of water made it the symbol of enlightenment in India. We also find plane trees (Platanus), as well as the ornamental flower Banksia, whose elongated stamina far outgrow their own petals, and macadamia nuts (Macadamia).

All Eudicots listed here save the two we’ve just seen form the clade Pentapetalae “five petals”, whose flowers are indeed formed by five-parted whorls -- five petals, five series of stamina, five carpels, and such.

4d3. Santalales: A member of Superasteridae, related to Asteridae here below. Named after sandlewood (Santalum), whose perfumed wood is sacred to the Hindu goddess Lakshmi. Here we also find mistletoe (Viscum album), a parasite bush that grows on tree branches, sucking nutrients through its roots, and spreading its seeds by sticking them to birds with a gluey (”viscous”) pulp.

4d4. Caryophyllales: Another Superasteridae.

Family Cactaceae includes all varieties of cactus, from the massive saguaro (Carnegiea gigantea) to the prickly pear (Opuntia ficusindica), which have turned their leaves into defensive spines -- all of them native of the Americas, except for Rhipsalis baccifera, which may have spread to Africa by sticking to birds its mistletoe-like fruits. Another family of succulents, the mostly-South African Aizoaceae, contains the bizarre Lithops, a little plant with rock-like leaves that surround a single flower. Family Amaranthaceae contains several edible plants, such as sugar beets (Beta vulgaris), spinach (Spinacia oleracea), and the “pseudo-cereal” quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa), as well as the saltbush (Atriplex) able to grow in salty sand. In this order we also find two unrelated clades of carnivorous plants: in one, the pitcher plant Nepenthes, which turned some of its leaves into water-filled insect traps; in the other, the sundew Drosera, which trap preys with sticky hairs, and the flytrap Dionaea, which do so with mobile beartrap-like leaves.

The carnivorous plant Drosera tokaiensis (Caryophyllales) from Japan. Drops of sticky sugary sap (drosos is Greek for “dew”) attract, trap, and drown insects. Leaves then curl toward the center to create as much surface contact as possible, while secreting digestive enzymes. Carnivorous plants generally evolve in regions where the soil is poor in nitrogen and phosphorus, but they still get the bulk of their energy from photosynthesis. (Wikipedia, Jan Wieneke)

4d5. Asteridae: A large group of Angiosperm orders, with some cellular and biochemical traits in common. In most, flower petals are partially or wholly fused together, but this might not be an ancestral feature.

4d5a. Ericales: Usually small and shrubby. At the center of this order we find heathers (e.g. Erica and Calluna), which form prairies on poor, acidic soils, as well as Rhododendron and the blueberry (Vaccinium) of boreal forests. Other members of the order include the kiwifruit (Actinidia); primroses (Primula); the Indonesian gutta-percha (Palaquium gutta), whose latex was used to insulate wires before the invention of plastic; genus Diospyros, which gives persimmon as fruit and ebony as wood; and finally the rather bizarre boojum (Fouquieria columnaris), whose pillar-like trunk towers over the Mexican savanna. Not enough? Camellias are here -- most importantly, tea (Camellia sinensis).

Boojum trees (Fouquieria columnaris, Ericales) in Baja California. The trunk, up to 20-25 meters tall, is covered in dense, short branches, each a few tens of cm long. (Wikipedia, Qnonsense)

4d5b. Lamiidae

4d5b1. Lamiales: Key of this order is family Lamiales, once called Labiatae “lipped” because of their bilaterally symmetrical flowers, whose petals form a support platform for pollinating insects. Their leaves sprout in pairs, each pair perpendicular to the adjacent ones, and are packed full of aromatic oils: indeed, here we find many of the herbs of Mediterranean cuisine, such as sage and rosemary (Salvia), thyme (Thymus), basil (Ocimum), mint (Mentha), as well as lavender (Lavandula). In another family, we also find the olive (Olea europaea) and ash trees (Fraxinus); elsewhere, the disquietingly-named “broom-rape” (Orobanche), a genus of parasitic plants that completely lacks chlorophyll and grows on the roots of other plants.

4d5b2. Gentianales: Several plants in this order have poisonous leaves, such as dogbane (Apocynum) and oleander (Nerium oleander). Most, however, will be more interersted in family Rubiaceae, as it includes not only Cinchona, whose bark provides quinine used to treat malaria before it could be produced synthetically, and madder (Rubia), used since antiquity as red dye, but also coffee (Coffea arabica).

A parasitic cluster of Orobanche flava (Lamiales), growing in Northern Europe. Note that this plant has no leaves, and no green parts at all, as it has completely lost chlorophyll. (Wikipedia, Jerzy Opioła)

4d5b3. Solanales: Family Solanaceae, whose petals are fused at the base into long tubes, is of greatest interest to humans, mostly because of the South American genus Solanum, which includes both tomatoes (S. lycopersicum) and potatoes (S. tuberosum). However, it also includes plants that produce more-or-less toxic alkaloids with various effects, such as bell and chili peppers (Capsicum), tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum), and the deadly nightshade (Atropa belladonna). Almost as important is family Convolvulaceae, with genus Ipomoea, which besides the several species of morning-glories also includes the sweet potato (I. batatas) and the water spinach (I. aquatica). All have distinctive circular flowers with fused petals. The family also contains Cuscuta, another genus of parasitic plants lacking chlorophyll that grows as a leafless vine on trees.

4d5c. Campanulidae

4d5c1. Aquifoliales: A rather small order, mostly made famous by the genus Ilex, which includes both the holly (Ilex aquifolium) with its waxy, spiny leaves, and yerba mate (Ilex paraguariensis), used to make a stimulant tea in South America.

4d5c2. Apiales: The central family Apiaceae was once known as Umbrelliferae “umbrella-bearing”, as their tiny flowers are gathered in branching, dome-shaped inflorescences. Like Lamiaceae they are often full of aromatic oils, and indeed they comprise such herbs and spices as coriander (Coriandrum), cumin (Cuminum), parsley (Petroselinum), and fennel (Foeniculum vulgare), as well as celery (Apium) and carrots (Daucus carota), but also the hemlock (Conium maculatum) whose juice killed Socrates. Elsewhere in Apiales we find ginseng (Panax) and common ivy (Hedera).

A stand of giant hogweed (Heracleum mantegazzianum, Apiales), a invasive species in central and northern Europe. Its sap is toxic and produces painful blisters, but only once it’s struck by sunlight. Note the umbrella-like inflorescences typical of Apiaceae. (Wikipedia, Huhu Uet)

4d5c3. Asterales: Here’s the other big one -- with some 33,000 species, family Asteraceae beats Orchidaceae for the title of largest family of the Plant kingdom. Once known as Compositae, for they have structures that would appear to be flowers but in fact are complex inflorescences: the large “petals” are in fact modified flowers that surround a bunch of smaller tube-shaped flowers. They are usually herbs, and infamous for often having little yellow inflorescences that all resemble each other. A great deal of them are known as daisies (e.g. Bellis perennis); after them, the sunflower (Helianthus annuus) is usually named as “type” of the family. Here we also find the dandelion (Taraxacum officinale), the thorny thistles (Cirsium) and their close relative the artichoke (Cynara cardunculus), lettuce (Lactuca sativa), sagebrush (Artemisia), and the giant-leaved burdock (Arctium), whose hooked seeds, by hanging onto animal fur for dispersal, inspired the invention of velcro. Other families of the order have more conventional flowers: for example, bluebells (Campanula).

Flower heads of the daisies Argyranthemum frutescens from the Canaries (Asterales). It is visible how the center of the heads is, itself, a cluster of smaller flowers. (Wikipedia, Forest & Kim Starr)

4d6. Saxifragales: A member of Superrosidae, related to Asteridae here below. Representatives include Liquidambar, sweetgum trees, whose resin is used as chewing gum and in herbal medicine, as well as Ribes, the genus of currants and gooseberries; witch-hazel (Hamamelis); peonies (Paeonia); and Saxifraga “stone-breaker”, which grows on cold, rocky ground. Particularly interesting is the family of Crassulaceae, or stonecrops, little succulent plants with whorls of thick, rubber-like leaves -- such as the hardy Sempervivum (“always-living”).

The Crassulacean from Madagascar Kalanchoe daigremontiana or “mother of thousands” (Saxifragales), a “viviparous plants” that generates hundreds of plantlets from the edge of its leaves. Note how they are developing leaves and roots even before detaching from the parent plant. (Wikipedia, CrazyD)

4d7. Rosidae: A large grouping of Eudicot order, without clear morphological common features.

4d7a. Vitales: A small order, but a precious one: grapes (Vitis vinifera) are here.

4d7b. Myrtales: A rather diverse group of herbs, shrubs, and trees, among which we find myrtles (Myrtus), cloves (Syzygium aromaticum), pomegranates (Punica granatum), and the 700 species of Australian Eucalyptus, which include the tallest flower plant in the world, standing over 100 meters tall.

4d7c. Malvidae

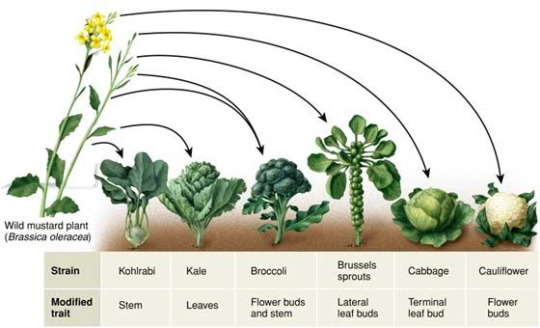

4d7c1. Brassicales: The family of Brassicaceae or Cruciferae (”cross-bearing”, because of their 4-petal flowers) contains radish (Raphanus sativus), turnips (Brassica rapa), several species of mustard, and woad from which blue dye was made since the Neolithic (Isatis tinctoria), as well as Arabidopsis thaliana, the plant most closely studied and raised in laboratories worldwide. But the star of the order is Brassica oleracea, from which selective breeding created a staggering variety of forms: kale from expanded leaves, kohlrabi from the stem, cabbage from terminal buds, Brussel sprouts from lateral buds, broccoli and cauliflower from flowers. Outside of Brassicaceae, this order includes the saltwort (Batis maritima), which grows on the edge of saltpans, and the papaya (Carica papaya).

Some of the many cultivated varieties of Brassica oleracea (Brassicales), all of them the same species. (Found on the web in multiple copies; I don’t know what the original source is.)

4d7c2. Sapindales: Stranely specialized families here. Burseraceae contains both frankincense (Boswellia sacra) and myrrh (Commiphora myrrha), with their odorous sap; Anacardiaceae comprises plenty of fruits, such as cashews (Anacardium occidentale), pistachio (Pistacia vera), and mango (Mangifera indica), but also the poison ivy (Toxicodendron). Finally, Rutaceae, the family of rue (Ruta graveolens) gives us all citrus fruit: lemons, limes, oranges, and grapefruits, all a complex web of hybrid species spread over the genus Citrus.

4d7c3. Malvales: Family Malvaceae is named after the mallow (Malva); it also contains the beautiful Hibiscus, whose carpels and stamina are fused into a single column, and the massive African baobab (Adansonia digitata); linden (Tilia) and kapok (Ceiba pentrandra) trees; and the infamous durian (Durio zibethinus), cola nuts (Cola nitida), and okra (Abelmoschus). But the most important members to us are probably the textile species -- cotton (Gossypium), whose seeds are coated by cellulose threads to catch the wind, and jute (Corchorus) -- and of course cocoa (Theobroma cacao), to which we owe chocolate.

4d7d. Fabidae

4d7d1. Malpighiales: In this order we find plants of great relevance for humans, such as flax (Linum usitatissimum, with whose stem fibers linen is made) and coca leaves (Erythroxylon coca); as well as mangroves (Rhizophoraceae), whose semi-aquatic roots have an enormous ecological importance; poplars (Populus) and willows (Salix); and the impressive passion-flower (Passiflora), with its part elevated in multiple tiers. Star of the order is the vast and diverse family of spurges (Euphorbiaceae), which, while recognizable by their milky white sap, have taken an enormous variety of forms, from succulent and spiny cactus-like species (e.g. Euphorbia obesa) to cassava (Manihot esculenta) to the rubber tree (Hevea brasiliensis). One more example? Rafflesia, the largest single flower in the world, which in fact is nothing more than a parasite flower drawing nutrients from other trees, and which takes the (red, fleshy, hollow, stinking) appearance of an animal carcass to draw its pollinators, carrion flies.

A tiny sample of the vast diversity of genus Euphorbia (Malpighiales). From left to right: E. myrsinites (Mediterranean), E. obesa (South Africa), E. pulcherrima (”Poinsettia”, Mexico), E. actinoclada (East Africa), E. dendroides (Mediterranean). (Wikipedia, Qwertzy2/Frank Vincentz/Sparrer 77)

4d7d2. Fabales: Dominated by family Fabaceae a.k.a old Leguminosae -- the family of beans. Here we find all types of legumes, from true beans (Phaseolus vulgaris) to peas (Pisum sativum) and from soybeans (Glycine max) to peanuts (Arachis hypogaea), whose fruits ripen underground. They also include the common clover (Trifolium), the touch-me-not (Mimosa) famous for its mobile leaves, and acacia trees (Acacia). These plants have bilaterally symmetrical (zygomorphic) flowers, and nodules in their roots that host symbiotic bacteria such as Rhizobium (see part 1). These bacteria can break down nitrogen gas in the atmosphere and convert it into ammonia, which can be taken up by plants as a source of reactive nitrogen. This allows beans to pack their seeds full of proteins, and explains the traditional use of clover and alfalfa in crop rotation to enrich the soil.

4d7d3. Fagales: Mostly an order of trees with clustesr of little, wind-pollinated flowers. Here we find a lot of trees familiar from northern temperate forests such as birches (Betula), alders (Alnus), hazelnuts (Corylus) (in family Betulaceae); beeches (Fagus), chestnuts (Castanea), oaks (Quercus) (in family Fagaceae); and walnuts (Juglans). The seeds of Fagaceae, enclosed in wooden shells, are common as food for humans; the bark of the oak Quercus suber provides cork.

Temme-Lauri, a 700-years-old oak tree (Quercus robur, Fagales) in Estonia. (Wikipedia, Abrget47j)

4d7d4. Cucurbitales: The star here is Cucurbitaceae, the family of gourds, squashes, and pumpkins (terms overlapping for various species of genus Cucurbita), as well as melons (Cucumis melo), cucumbers (Cucumis sativa) and watermelons (Citrullus lanatus). They are all vines with large fruits that are essentially massive berries, with a thick rind and seeds embedded in a fibrous pulp. Begonias (Begonia) are elsewhere in the order.

4d7d5. Rosales: The order is of course named after roses (Rosa), but it also includes a great variety of fruit trees and shrubs closely related to roses, such as apples (Malus) and pears (Pyrus), strawberries (Fragaria), thorny blackberries (Rubus) with their compound fruits, and the many-formed genus Prunus, which contains at once peaches, apricots, plums, cherries, and almonds. (Incidentally, the true fruit of Prunus is the woody pit, which defends seeds packed in turn with cyanide; the edible pulp is a secondary coating.) All these species fall in family Rosaceae; all non-Rosaceaean Rosales have small, wind-pollinated flowers. Almost as rich, family Urticaceae is named after nettles (Urtica), which defend themselves with needles full of formic acid, but also includes fig trees (Ficus), hemp (Cannabis) and the hops (Humulus lupulus) used to make beer. Elsewhere in Rosales we also find elms (Ulmus) and mulberries (Morus), whose fresh leaves are the only suitable food for silkworms.

Summary. Dates (mostly based on Bell &al 2010) are always in million years before the present.

Sources

Bell &al 2010, “The age and diversification of the Angiosperms re-visited” (link)

Crane & al (2004), “Fossils and plant phylogeny” (link)

Novikov & Barabasz-Krasny (2015), “Modern plant systematics” (link)

Qiang & al (2004), “Early Cretaceous Archaefructus eoflora sp. nov. with Bisexual Flowers from Beipiao, Western Liaoning, China” (link)

Sánchez-Baracaldo & al (2017), “Early photosynthetic eukaryotes inhabited low-salinity habitats” (link)

Singh (2019), Plant Systematics: An Integrated Approach (4th edition), CRC Press

Simpson (2019), Plant Systematics (3rd edition), Academic Press

Willis & McElwain (2002), The Evolution of Plants, Oxford University Press

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

Dandelions are also fucked up. There are sexually reproducing diploid and asexually reproducing triploid lineages and they look the same. Also the triploids can still get genetic material from the diploids somehow and benefit indirectly from sexual reproduction.

love that for them <3 thank u dandelions. plants LOVE fucking silly-ways

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Worldbuilding: Heterozygote Advantage

One of the interesting facets of how DNA works on Earth is, so long as you’re one of most eukaryotic organisms, you generally have two separate copies of each and every gene in your genetic makeup.

There are, of course, exceptions.

See the sex-determining chromosomes in mammals, and the completely different ones in birds. Not to mention some weird triploid fish and amphibians. And archaea and prokaryotes have their own bizarre stunts; check out bacterial plasmids for some interesting stuff, including why some varieties of E. coli are downright deadly. But most of the time, this holds. Two sets of chromosomes, giving the possibility of two different alleles for each gene.

Like most parts of life, this has its ups and downs. You might have two copies of the same allele (homozygous), meaning if the protein or RNA produced is good, you’re good - but if it’s not, you’re screwed. See a lot of cheetah populations, ow. If, however, you’re a member of a larger population with more variety, you’re very likely to have two different alleles (heterozygous). Which could be good, bad, or neutral. Or mostly just ignored, until it’s suddenly very important indeed. Like blood types. Most of the time they don’t matter; so long as you’ve got healthy blood circulating you’re good. But then you run into cases of transfusions, or epidemic disease, and your blood type matters a lot.

For the record blood type O seems to have a better resistance than others to smallpox and a few other crowd diseases, but is more vulnerable to cholera. Roll the dice.

Cholera and malaria seem to have selected for heterozygote advantage in humans. At least, we are darn near sure malaria infections selected for sickle-cell genes and a few other blood mutations. We’re less sure on cholera and dysentery selecting for cystic fibrosis genes, but the fact that defective gene pops up so frequently seems to indicate there was selective pressure to keep it in the gene pool.

Here’s where your worldbuilding should come in, if you’re of a biological mindset. Fantasy or SF, there should be some interesting selective pressures on your creatures and your characters’ populations. Low gravity? Bet your characters need more RBCs and oxygen-uptake capacity, look into high-altitude populations for what might thrive. High mana exposure? Certain groups might be extremely magic-resistant, unable to use magic but also shaking off curses like rain. Others might be very sensitive to magic, for better or worse. Still others might have an aptitude, or resistance, to specific types of magic. (See elemental benders.)

And if you cross two different races, or species, all bets should be off. See the mule - universally acknowledged to generally be smarter, tougher, and stronger than either horses or donkeys. Just (usually) sterile. Of course, you could ignore this completely; humans tend to have ways of getting around limitations. But it might be interesting to contemplate, oh, why some space colonies work, and others don’t; or how a vampire can prey on a whole town and yet only a few bodies rise....

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Trilogene Seeds Launches Revolutionary Triploid THCa Cannabis Seeds

Key Takeaways:

Innovative Breakthrough: Trilogene Seeds introduces new triploid THCa cannabis seeds, enhancing cultivation with multiple benefits.

Enhanced Features: These seeds offer reduced seed production, seedless flowers, higher yields, and improved flower morphology.

Genetic Advantages: Triploid seeds prevent cross-pollination and enhance plant qualities by being genetically sterile but…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

most miserable tropical plant on this gay earth. native to southeast asia. worldwide food staple. triploid mutant. vulnerable to every disease. wretched symbol of neocolonialism. hates wind. looking at it puts that one tally hall song in my head.

0 notes

Text

GenoTriplo: A SNP genotype calling method for triploids

http://dlvr.it/T3jr6q

0 notes

Text

Sexual Reproduction in Flowering Plants-NCERT Solutions Class 12

Sexual reproduction in flowering plants is a captivating and intricate process that plays a pivotal role in the life cycle of angiosperms, the largest and most diverse group of plants on Earth. Unlike their non-flowering counterparts, flowering plants have evolved a sophisticated system of reproduction involving specialized structures known as flowers. These flowers serve as the epicenter for the fascinating dance of pollination, fertilization, and seed development. The intricate interplay between male and female reproductive organs within these botanical wonders ensures the continuity of plant species and contributes to the breathtaking diversity of the plant kingdom. In this journey through the realm of sexual reproduction in flowering plants, we explore the mechanisms, adaptations, and significance that make this process a cornerstone of the plant life cycle.

Here is an overview of sexual reproduction in flowering plants Class 12:

Sexual Reproduction in Flowering Plants:

1. Introduction:

Flowering plants (angiosperms) undergo sexual reproduction to produce seeds and ensure the continuation of their species.

2. Structure of a Flower:

Flowers are reproductive structures consisting of sepals, petals, stamens, and pistils.

Sepals protect the flower in the bud stage.

Petals attract pollinators.

Stamens produce pollen (male reproductive cells).

Pistils contain the ovary, style, and stigma (female reproductive structures).

3. Pollination:

Transfer of pollen from the anther (male part) to the stigma (female part) of a flower.

Can be classified as self-pollination (pollen transferred to the same flower or another flower on the same plant) or cross-pollination (pollen transferred between flowers on different plants).

4. Fertilization:

Fusion of male and female gametes to form a zygote.

In flowering plants, the male gamete (sperm) is in the pollen, and the female gamete (egg) is in the ovule within the ovary.

5. Development of the Seed:

After fertilization, the ovule develops into a seed, and the ovary develops into a fruit.

The seed contains the embryo, endosperm, and seed coat.

6. Double Fertilization:

Unique to angiosperms, involving the fusion of one sperm with the egg to form a zygote and another sperm with two polar nuclei to form a triploid cell (which develops into the endosperm).

7. Seed and Fruit Formation:

The ovule develops into a seed, and the ovary develops into a fruit.

The fruit protects the seed and aids in seed dispersal.

8. Seed Germination:

The process by which a seed develops into a new plant.

Requires water, oxygen, and suitable temperature conditions.

9. Agents of Pollination:

Pollinators include wind, insects, birds, and animals.

Adaptations in flowers enhance successful pollination.

10. Types of Pollination Syndromes:

Flowers have characteristics that attract specific pollinators, such as color, scent, and shape.

11. Significance of Seed and Fruit Formation:

Ensures the survival and dispersal of plant species.

Seeds carry genetic information to produce new plants.

These are the fundamental aspects of sexual reproduction in flowering plants. Students may delve deeper into the details of each process and study specific examples for a comprehensive understanding.

#biology#botany#11thclass#science#9thclass#chemistry#class 8#foundation#11th class#vavaclasses#class 12#cbse#ncert#higher education#student#exam season#cbse school#ncertbooks#ncertsolutions

0 notes