Text

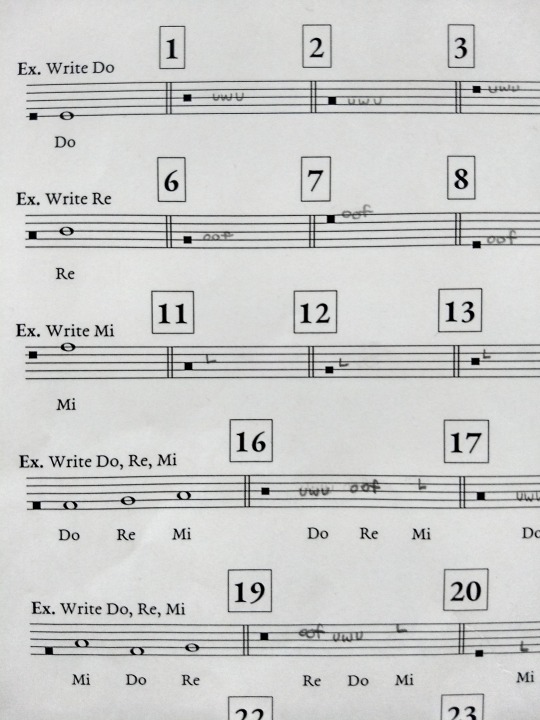

As a first year music teacher I've seen kids a lot of very weird things, but this absolutely sent me

3 notes

·

View notes

Video

vimeo

This is why we study music. This is why we sacrifice hours, meals, and sleep. We rehearse, we perform, and we study theory, AP, and sight-singing. It's for the occasions like these... when we can bring joy to someone, even in the final days of their life. Rest in Peace David, it was an honor to sing with you. Our intonation wasn't perfect, but the harmony was.

0 notes

Text

Summer Update

I finished my junior year of college. Here’s what’s been happening.

June: I had a musical and emotionally transformative experience at the Michigan State University’s Conducting Symposium. I was blessed to be able to learn from Dr. Kevin Sedatole, Dr. David Thornton, Kevin Noe, and guest clinician Dr. Jamie Nix (Columbus State). I met some wonderful people from around the country, and my conducting was lightly praised by the legendary John Mackey!

May: A saxophone quartet premiered my new composition, hot tongues & burnt coffee at the Composers Club Concert. I finished off my junior year by conducting the Symphonic Wind Ensemble for the pre-commencement concert, performing Frank Ticheli’s Simple Gifts and Cajun Folk Songs. Many thanks to Scott Downs, Patrick Neff, and Harvey Benstein!

April: I founded a contemporary music ensemble, and made our debut performance in Faye Spanos Concert Hall, jamming to Ted Hearne’s But I Voted For Shirley Chisholm.

0 notes

Text

hot tongues & burnt coffee

After a semester of composition lessons with Dr. Coburn, I produced a saxophone quartet. The name “hot tongues and burnt coffee” stem from my Thursday morning residences at Noah’s Bagels with a cup of hot coffee to help me cram-write before my afternoon composition lesson.

youtube

0 notes

Text

An informal study: Bernstein’s Ḥalil

Ḥalil … is formally unlike any other work I have written, but is like much of my music in its struggle between tonal and non-tonal forces. In this case, I sense that struggle as involving wars and the threat of wars, the overwhelming desire to live, and the consolations of art, love, and the hope for peace. It is a kind of night-music which, from its opening twelve-tone row to its ambiguously diatonic final cadence, is an ongoing conflict of nocturnal images: wish-dreams, nightmares, repose, sleeplessness, night-terrors and sleep itself, Death’s twin brother.

I never knew Yadin Tanenbaum, but I know his spirit.

—Leonard Bernstein, program notes for Ḥalil

In 1973, Israel occupied the Sinai and Golan Heights regions of Egypt and Syria, respectively. This was the result of the 1967 Six-Day War, a decisive Israeli victory which ended with a UN brokered ceasefire.

On 6 October 1973, on the Jewish holiday of Yom Kippur, Egyptian and Syrian military forces broke the ceasefire and launched a surprise attack on Israel, hoping to regain the territory they lost. Both sides were backed by massive resupply efforts by their respective allies, the Soviet Union and the U.S. The result was a twenty-day war which resulted in tens of thousands of deaths, the eventual creation of the Camp David Accords, and a near-confrontation between the two Cold War nuclear super-powers.

Among the Israeli casualties was the nineteen-year-old Sgt. Yadin Tannenbaum, who was killed along with his comrades when a shell hit his tank in the Sinai. He was a musical prodigy, “A flutist, he was singled out for praise by conductor Leonard Bernstein. He had rejected an offer to serve in the army orchestra and opted for a combat unit” (Rabinovich 123).

Following the tragedies of the Yom Kippur War, Leonard Bernstein was approached by Tannenbaum’s parents asking him to write a piece in memory of their son (Mazey).

To the spirit of Yadin, and to his fallen brothers

Ḥalil, the Hebrew word for “flute,” premiered 27 May 1981 in Tel Aviv’s Frederic Mann Auditorium featuring Jean-Pierre Rampal as the soloist, with Leonard Bernstein conducting the Israel Philharmonic.

In the 1982 New York Philharmonic program notes for Ḥalil, Richard Freed points out that Leonard Bernstein “has yet to produce a work which he calls a concerto,” attributing this largely to the “theatrical or dramatic substance” of the composer’s works. Indeed, Ḥalil is a single-movement nocturne for solo flute, string orchestra, and percussion.

In its full form, the score calls for solo flute, strings, harp, a wide assortment of percussion, as well as a piccolo and alto flute “seated within the percussion section, preferably invisible to the audience.”

The available reduction of Ḥalil is perhaps the biggest testament against the piece being labeled a concerto. Most solo works are available with a piano reduction for performance in smaller venues and recitals. However, the reduction for Ḥalil is not just for flute and piano. Bernstein makes the point of including a reduced percussion part as well.

This is because of the role that the percussion plays in the piece. As part of many juxtapositions used by the composer, percussion characterizes the violent war against the solo flute, the spirit of Yadin. In this sense, the piece is probably closer to a chamber work than it is a concerto. The programmatic content can also categorize the work as a tone-poem.

Another prominent juxtaposition in Ḥalil is the piece’s “struggle between tonal and non-tonal forces” (Bernstein). The piece opens with a haunting tone-row, and regularly switches between tonal music and atonal passages. Often in conjunction with the tonal quality, the piece alternates between “moments of lyricism and violence…” (Burton 465).

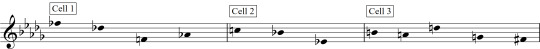

The introductory tone-row can be grouped into three different cells (Figure 1), each taking a portion of the twelve chromatic notes and creating various motifs (Figure 2). These motifs are used throughout the piece in both tonal and atonal contexts, and will be explained in more detail later.

Figure 1. The complete tone row, divided in three cells

Figure 2. Basic motifs used in Ḥalil

Introduction: As mentioned before, the piece begins with the introduction of the tone-row. By the end of mm.8 all the pitches have made their appearances, and then the row is played in retrograde. Once it completes its retrogression, the tone row is sent forward once again, this time hauntingly echoed by the alto flute. Finally, the introduction ends on a variant of Motif 1, setting up the transition into the next section.

Ballad (mm.26, Andante tranquillo): The ballad is the first tonal section of the work, rooted in D-flat major. The central theme for the piece is introduced here. The solo flute plays a blooming melody based on Motif 1 over smooth arpeggio accompaniment. In the case of Motif 1’s development into the melody, exact intervals are not followed. Rather it is explored through its basic contour (high, mid, high, mid, low, mid-low). At mm.41, the flute plays a quarter-note quintuplet figure that is widely used throughout the piece, Motif 2a (Figure 2). This is a derivative of Motif 2, the combination of a descending major second and an ascending fourth. The motif is set backwards and “stacked,” creating a descending teeter.

The flute drops out at mm.44 and the melody is continued on a solo violin. As the melody progresses, Motif 2 begins to pervade the increasingly dissonant texture, taking over at mm.52, Andante con moto. The flute, biting, returns with Motif 1 in similar fashion to the beginning. It quickly dies down, and the ballad theme is brought back by in the first violins. Meanwhile the soloist plays counterpoint- a ballad melody based on Motif 2, with an appearance of Motif 3. Motif 1 makes a brief appearance by the flute at mm.70, just as the ballad finally dies down.

Motif 2a Development (mm. 75, Con moto ardente): The ballad sets up the development section by setting Motif 2a in a descending sequence. The development features Motif 2a in a variety of transformations and is a dueling “non-tonal” section. The main idea of the development is an antecedent-consequent relationship. The antecedent is essentially a double set of Motif 2a, in which the first set is inverted. The consequent is similar in structure to the antecedent; a pair of quintuplets including an inversion. The intervals for these quintuplets are more varied than that of Motif 2a, however (Figure 3). The odd metric structure, lack of steady tempo, and absence of tonal center makes this development restless and unsettling. A solo viola and the flute toss the melody around, slowly building into mm.81, Con anima. The orchestra violently throws the motif and melody around in a cacophony of diminutions, trills, and transpositions. This also marks the first entrance of rhythmic percussion (previously used only for sparse accenting and rolls).

Figure 3. Melody featured in Motif 2a Development

The violence quells shortly after it begins, and the flute re-enters. Paired once again with the alto flute, the flute plays notes very reminiscent of the introduction (Figure 4). The development diminishes into a mysterious murmur.

Figure 4. Comparison of mm.16 and mm.102

The “CBS” section (mm.113, Allegro con brio): The quiet ending of the development is ripped open with a xylophone glissando to reveal a bright E-flat major fanfare. This is built squarely on the Motif 2 using the exact pitches as first found in the introduction. The fanfare clears the way for a bouncy F major accompaniment in 3/4 meter. The flute enters with the melody in A-flat major, using primarily three-bar phrases.

This bright “stereotypical-Bernstein” section was not originally written for Ḥalil. Jack Gottlieb notes that, like many composers, “Bernstein recycled musical materials when they suited his needs” (Gottlieb, Ḥalil). In his memoir Working with Bernstein, Gottlieb writes about the symbiotic relationship of Dybbuk (1974), CBS Music (1977) and Ḥalil (1981), noting that both the preceding development and the “CBS” sections are recycled:

The first is a mother lode that feeds into the other two. Least known is the middle work, written at the behest of William Paley, head of the CBS broadcasting company. Paley, on the board of the NYP and the one who supported the Young People’s Concerts, asked LB to write theme music for the fiftieth anniversary of the network in 1978…

The head motif consists of three notes: C, B-flat (B in German) and E-flat (Es in German) to stand for the CBS call letters. This profile of a descending major second and a rising interval of the fourth happens to be indigenous to parts of the Dybbuk ballet, particularly in the pas de deux section titled “LC” (for the doomed bride and groom, Leah and Chanon), dated “4 Feb. ’73.” It was a section that was eventually cut from the ballet, but subsequently thirteen bars from it were incorporated into the flute concerto, Halil (at con moto, ardente). This is done so smoothly that the lift would not be apparent even to discerning ears. But more front and center, LB organically merges the complete “Fanfare and Titles” of the CBS Music into Halil (Allegro con brio). No seams show. It is a feat of legerdemain accomplished by a musical magician at the top of his game.

Why did Bernstein choose to use his CBS Music, nearly verbatim, in Ḥalil? Although there is a possibility that it was not much more than an arbitrary decision to recycle music, the more likely explanation is found by understanding CBS’s role in the programmatic narrative Ḥalil is based on.

youtube

The pace of the peace processes following the ceasefire of the Yom Kippur War was slow. Egypt and Israel, led by President Anwar Sadat and Prime Minister Menachem Begin, were reluctant to meet face to face, and they had no established diplomatic relations. Soon, however, Sadat grew weary of the slow pace. In 1977, after hearing rumors of Sadat’s wishes to visit Israel, Walter Cronkite of CBS arranged a televised interview with the Egyptian President, “I asked him about preconditions for an Israeli visit, and he started rattling off the familiar list of Arab demands. It sounded like the denial I expected. To make certain, I asked him again if these were his conditions for going to Israel. Sadat said no, they were his conditions for peace. He was ready to go to Israel anytime.” Sadat explained that he was waiting for a proper invitation.

Later that day, CBS secured Begin via phone for an interview on-air with Cronkite. Begin stated “…I will, during the week, transmit a letter from me to President Sadat, inviting him formally and cordially, through the good offices of the United States, to come to Jerusalem.”

At that moment, 30 years of Arab-Israeli history were reversed. Sadat was set to go to Israel the following Saturday in the first direct exchange between the two countries. “Never in my career had I watched so many formalities swept aside so fast,” Cronkite noted. “The next morning, the papers were hailing CBS News as a force of media diplomacy. Time magazine talked of Cronkite's coup.”

Walter Cronkite and CBS were the catalysts of peace. The events they sparked led directly up to the signing of the historic Camp David Accords of 1978 and the subsequent Egypt-Israel Peace Treaty of 1979. The work of Cronkite and CBS symbolized what Bernstein described in his program notes as “the hope for peace.” His inclusion of CBS Music, which premiered during the time of the diplomatic events, is an appropriate celebration of that sentiment.

At mm.153 the score departs from the celebratory music, entering a lopsided 5/8 development. The piccolo, heard for the first time, mimics the flute’s playful melody over a light percussion accompaniment. The disjunct figures center around Motif 2 (and naturally the “CBS” theme) and are somewhat reminiscent of Con moto ardente: groups of tonally ambiguous notes in a quintuple setting.

The F major “CBS” melody returns in the strings at mm.175. As the 3/4-meter melody is played once again, the flute interjects with passages in an independent 5/8 feel. At mm.195, the meter fully switches to 5/8 with a subito-piano dynamic. It moves directly into 7/8, and an uncomfortable urgency is developed. Suddenly battery percussion enters, the strings bark and screech, and the piece launches into the cadenza.

Cadenza (mm.202): The cadenza is an emotional slurry featuring the various motifs and themes of the piece. “Bernstein was reluctant to reveal that the pyrotechnical cadenza section depicted the slaughter of the Israeli soldier, but critics were quick to note this programmatic aspect of the work” (Gottlieb, Ḥalil). Bernstein calls for qualities of “shrieking” and “panting” in the first section of the cadenza. The middle of the cadenza is a haunting, almost limping, “childlike” passage. It transitions into a 5/8 meter at rehearsal H, revisiting material from the development. At rehearsal J the flute and piccolo perform material from mm.153 again. This time, however, it is a half-step up, desperate and “breathy.” Finally, the flute closes the cadenza with Motif 2 and the highest note of the piece- a screeching F7 (Figure 5).

Figure 5. The flute’s final notes of the cadenza

The Ending (mm.203, Largo): Following the cadenza, the solo flute rests for nearly 60 bars of music. It is “the sleep after the terror of an unmistakable night of battle,” Humphrey Burton writes. “…the solo flute falls silent as if to suggest Yadin’s wasteful death…” (Burton 465).

At the beginning of Largo, the orchestra loudly plays music based on Motif 2/2a before opening into the passionate ballade theme. At mm.218, Andante amoroso, the alto flute reenters, playing a mournful duet with a solo viola, quintuplet figures based on Con moto ardente. Burton suggests that the hidden alto flute is “a touching metaphor for the spirit departing from Yadin.” At mm.230, Più lento, the piccolo enters, replacing the viola in the duet.

The orchestra plays a final iteration of the ballad beginning at mm.237, Adagio. Gaps in the middle of the phrases are like mourning chokes or a painful loss of words. The piccolo and alto flute make a final return, playing a series of half-steps. These steps, somewhat evocative of the final notes of West Side Story, are played three times, each time transposed a half-step up. The implied leading-tone to tonic relationship of these half-step continuously shifts the perceived tonality leading to the ending.

The solo flute makes a final entrance with a C-natural and a D-flat played over strings on a D-flat major chord, seemingly ending the piece in a simple major mode. However, the harp plays a descending arpeggio of F-flat, D-flat, and F-natural, obscuring whether the piece ends in D-flat major or D-flat minor (Figure 6).

Figure 6. The harp’s final notes

This will be our reply to violence: to make music more intensely, more beautifully, more devotedly than ever before.

—Leonard Bernstein, 25 November, 1963

Works Cited

Bernstein, Leonard. Ḥalil. 1981. New York, NY: Boosey & Hawkes, Inc., 1981. Print.

Cronkite, Walter. “Media Played Role in '70s Mideast Peace Process.” All Things Considered, NPR, 15 Jan. 2007, www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=6861044.

Gottlieb, Jack. “Ḥalil.” Milken Archive of Jewish Music, www.milkenarchive.org/music/volumes/view/sing-unto-zion/work/alil/.

Gottlieb, Jack. Working with Bernstein: a Memoir. Amadeus Press, 2010.

MaineTVClips. “CBS On the Air - 50 Years of CBS.” YouTube, YouTube, 20 June 2008, www.youtube.com/watch?v=ix8tJx-yIuw.

Mazey, Steven. “Symphony Holds Free Preview.” Ottawa Citizen, 15 May 2008, www.pressreader.com/canada/ottawa-citizen/20080515/282385510251464.

New York Philharmonic Leon Levy Digital Archives, and Richard Freed. “New York Philharmonic Program (ID: 4560), 1982 Mar 24, 25, 26, 27, 30.” Edited by Phillip Ramey, New York Philharmonic: Viewer, archives.nyphil.org/index.php/artifact/3dcd7737-5add-46c6-800e-17450ea4a24b-0.1/fullview#page/1/mode/2up.

Rabinovich, Abraham. The Yom Kippur War: the Epic Encounter That Transformed The Middle East. Random House Inc, 2005.

“Six-Day War.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 9 Dec. 2017, simple.wikipedia.org/wiki/Six-Day_War.

“Yom Kippur War.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 5 Jan. 2018, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yom_Kippur_War.

Note: This analysis was written in preparation for my performance of this piece on 3 February 2018 for my Junior Recital at the University of the Pacific in Stockton, CA.

0 notes

Photo

I’m very grateful for these five folks for rehearsing my brass quintet in preparation for its premiere this Wednesday night at the Composers Club Concert!

0 notes

Photo

I was tasked this summer with typesetting Geraldine Mucha’s 1998 Woodwind Quintet from a handwritten photocopy. Tonight, I finally got to hear it performed live by the Pacific Arts Woodwind Quintet as part of an exquisite evening of quintet literature.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

BrokenTimePiece & Legally Blonde

I don’t think I’ve ever overbooked myself so hard in my entire life. Unfortunately, booking myself for too much is my tragic flaw.

This week was hectic. On Monday, for example, I had three back-to-back rehearsals from 5pm-12:30am. Or look at Thursday, when I had no breaks longer than 45 minutes between 7:30am and 11pm. Or Saturday, a two show day with a 12am and an 8am. Or indeed today, Sunday, when I conducted Act I of the final show of the Legally Blonde production here with TAP, and then went over to rehearsal and perform the premiere of Scott Nelson’s eclectic senior composition project BrokenTimePiece.

My baton survived through nearly all of that. Until about the last minute of BrokenTimePiece, when at the climax of the piece I somehow broke it with my land hand mid-performance. Literally a broken time piece.

Is this symbolic?

1 note

·

View note

Text

Cadence-less Development Section

Much of western classical music is built on cadences. In a sonata by Mozart, for example, predictable, consistent cadences mark the phrases that make up the two sonata themes. Once you exit the exposition and dive into the development section, clear cadences are a little harder to find. Music just keeps moving around, modulating, and developing.

So, what’s been going on with me for the past few months?

May: Following my conducting clinics with Dr. Hammer and MJ Wamhoff, I had the honor of conducting Pacific’s Symphonic Wind Ensemble during the University’s Commencement festivities. I ended up conducting movements II and IV of Ticheli’s Simple Gifts. Right after commencement, I traveled to Cherry Valley, New York to begin my internship at the Glimmerglass Festival.

Mid-May through July: My time working at the Glimmerglass Festival as a Young Artist Program Residence Manager Intern was a little rough. I was having a hard time socially with folks who were older than me, and my job was lackluster and a little degrading to say the least. However, I did learn a lot about musicianship and the professional world of music. I had the opportunity to observe exemplary musicians at work. Guest artists Donald Palumbo (Chorusmaster of the New York Metropolitan Opera), Stephen Schwartz (Tony Award-winning composer), and Kevin Stites (veteran musical director) offered amazing insight.

August: I ended up leaving the job early; at times you must recognize when it’s not worth staying in a position. I traveled to Boston with my parents to do some sightseeing, and I also got to meet up with an old friend of mine who was working at Tufts University over the summer. We also visited the Verne Q. Powell flute factory where my parents were explained (in a two-hour tour) the reason the flute they bought me costs so much. Afterwards we drove back up to New Jersey, where my mom had arranged to reunite with some old high-school friend. Then up to the Big Apple. I caught Prince of Broadway (in previews), Miss Saigon, The Play that Goes Wrong, and Georama, in addition to Groundhog Day which I caught during my internship at Glimmerglass.

Returning to California early meant I had time to breathe, make various appointments, and slowly move into my new apartment at school. I had the pleasure of having coffee with my favorite professor, Dr. Rose, who just left his decades-long tenure at Pacific for a position at Stanford University. There are some people who are just too pure for this world. Dr. Rose is one of them.

Late-August through October: Okay. Let’s quickly talk about “Junior Block.” J Block is part of the music education program at Pacific. It’s where you talk about educational psychology, music, and the profession of music education. It’s the time when you really begin to observe teachers in the field and start to teach. I am in J Block.

In addition to the crazy workload in the class, I have several hours of fieldwork each week. Two-hours a week are spent teaching my very own musical classes to my very own students. I have second graders at Spanos Elementary School, and sixth graders at McCandless STEM Charter School, both in Stockton.

All on top of my other classes. But it’s such an enriching experience for me and the students. Seeing how music can affect children is phenomenal. Enough J Block. Moving on.

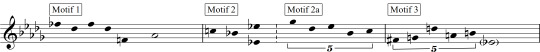

I also made the choice to schedule a solo flute recital next semester. I will be performing Maria Grenfell’s delightful unaccompanied solo Four Pooh Stories (1992, New Zealand), Karlheinz Essl’s electro-acoustic piece Sequitur I (2008, Austria), and Leonard Bernstein’s jarring and haunting nocturne Ḥalil (1981, United States) for flute, piano, and percussion. As you may have noticed, all the works were written within the last 40 years, and come from all over the globe.

In September, I had the pleasure of doing some work for Dr. Hammer’s professional ensemble, the New Hammer Concert Band. I sat in for all their rehearsals and took notes on rehearsal techniques, and I designed a new logo and concert poster. During the weekend of the performance, and Dr. Hammer was kind enough to offer to let me conduct the ensemble in rehearsal for a bit- what an experience! Conducting an ensemble of such a caliber is an intense musical experience. At the end of that same rehearsal, Dr. Hammer assigned me to help director Clubhouse Studios, the company he had contracted to video record the performance. From 5pm to 2am, and following morning (day of the concert), I marked up about 300 pages of score in preparation for the concert, ran a few test-runs to direct the camera shots, and hey, ho! away we go! we recorded the concert.

In September, I was also offered the job of Choral Assistant with the Stockton Youth Chorale program under the direction of Joan Calonico. I run warm-ups and sight-singing with children from third to eighth grade. This opportunity has forced me to work on my choral pedagogy techniques, as well as my classroom management skills.

I turned 21 in the first week of October. Some people like to celebrate their birthday by playing laser tag, going to the beach, or getting hammered. I chose to spend 9 to 5 at a professional development workshop with Little Kids Rock, an organization committed to helping teachers bring Modern Band to music education. It was an inspiring day and a day where preconceptions were turned on its head.

I’m sure I’m missing somethings here and there, but never mind those. What’s it look like moving forward?

November: Working with the pit orchestra for TAP’s production of Legally Blonde; conducting Scott Nelson’s senior project BrokenTimePiece. Then I’ll be watching Massenet’s Manon and John Adam’s premiere production of Girls of the Golden West at the San Francisco Opera.

December: Lots of various performances. Then the annual Palo Alto Caroling Corps!

I’ll try to update a little more often, but God only knows what my schedule turns into.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Whaddya know? I’m putting on a recital next semester. Since I’m performing Maria Grenfell’s Four Pooh Stories, I figured this would be an appropriate poster.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

"Our job is to draw the music out of the student, not to drum it in." -Little Kids Rock workshop

0 notes

Photo

The perks of being back home is that I can make white wine, golden raisin & fennel seed ice cream.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Improvised desserts

It’s been very hard to cook here with no actual kitchen. So with leftovers, a microwave, and a toaster oven, I present two desserts.

Plum upside-down cake (leftover pancake base)

Berry crumble (English muffin base)

0 notes

Text

2¢: Trump-Caesar, Theatre, and Line Crossed

There has been a lot of talk going on about the recent production of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar at the Public Theater in New York. Let me put these two pennies on the table.

The issue is this

The Public Theater’s production of Julius Caesar blatantly depicts the titular character as President Donald Trump; there is uncanny resemblance in his appearance, among other similarities. The character is murdered as part of a conspiracy by other characters. Critics of the free “Shakespeare in the Park” claim that it incites violence; corporate sponsors of the Public have withdrawn their funding or distanced themselves from the production.

Critics that merely cite that the production as "‘Trump’-stabbing” understand the situation and the play poorly. The production encourages violence just as much as the musical Les Miserables condones shooting a child. (I can’t help but to recall a similar situation in which the Metropolitan Opera’s 2014 production of The Death of Klinghoffer was criticized and protested against as glorification of terrorism.) On the contrary, Julius Caesar is the condemnation of “those who attempt to defend democracy by undemocratic means.”

“It’s an odd reading to say that it incites violence, because the meat of the tragedy of the play is the tragic repercussions of the assassination.... “The play could not be clearer about the disastrous effects of violence.” -Bill Rauch, Artistic Director of the Oregon Shakespeare Festival (The New York Times)

In a New York Times interview Oskar Eustis- the Public’s artistic director and director of the controversial production- asserts that “This production does not hate Julius Caesar... This production is horrified at his murder.”

In fact, the play revolves more around the downfall of Brutus as the tragic protagonist; he is vital to the planning and execution of Caesar’s assassination. Following the assassination is a show of the deadly repercussions of usurping democracy. In a way, the production speaks against those who may have wished an unfortunate demise of our president.

The Public Theatre has been the birthplace of many well known shows, including A Chorus Line, and more recently Hair, Fun Home and Hamilton. On their website they claim to be “an advocate for the theater as an essential cultural force, and leading and framing dialogue on some of the most important issues of our day.” And that is precisely what they have done. In this “hyperpartisan age,” there are loud voices across this internet.

From the right-wing

The president’s son weighs in on this situation in a response to a tweet from Fox News.

“I wonder how much of this 'art' is funded by taxpayers? Serious question, when does 'art' become political speech & does that change things?” --Donald Trump, Jr. (Twitter)

This is an interesting point. The Public Theater, according to Eustis in a New York Times interview, is mostly funded through private donors, claiming that the loss of their corporate sponsors are not a huge deal financially. However they do receive some government funding. The City of New York, which provides funding to the Public’s production, stood by their sponsorship, citing that otherwise it would amount to censorship. The National Endowment of the Arts, although having previously funded other projects at the Public, stated that they have not been funding the controversial production in any way. It should be noted that people speculate that their very upfront announcement has to do with their ever slimming chances of existence under the Trump Administration.

This issue I take with Trump Jr.’s tweet is the use of quotations around “art”. Despite any differences one has to a work of art, it remains 100% art. One may have many disagreements. It could be political, like this production, or the songs of Pete Seeger. They could be artistic, such as the case of Jackson Pollack’s painting techniques. John Cage’s 4′ 33″ is infamous for drawing philosophical debate in music. Regardless, each work is art within its own right. Trump Jr.’s question of when art crosses the political line demonstrates a lack of understanding of art. Art is rarely a “feel good” product. It’s more often packed with emotion, rhetoric, story, and commentary; political speech and art are not mutually exclusive (ask Shostakovich). If the arts do not comment on both the concord and discord of today, then it has neglected its humanitarian role in our society.

From the left-wing

“It’s an upsetting play, but if there’s a production of ‘Julius Caesar’ that doesn’t upset you, you’re sitting through a very bad production... It’s clear that the corporate sponsors who pulled out are just being cowardly and caving in to a lot of cranky right-wing people because Breitbart and Fox News told them to.” --Tony Kushner, Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright (The New York Times)

There are a lot of folks calling for the boycott of Delta Airlines and the Bank of America due to “financial censorship.” While I cannot deny that this is financial censorship, I can sympathize with the actions of the corporations. After all, their withdrawal is a form of expression in of itself.

The corporations

Three corporations associated with the Public’s production have distanced themselves. Most recently American Express has backed away from the production. Bank of America also withdrew their funding from the production, but announced that they will remain a sponsor for Public Theater. Delta Airlines, however, completely backed out their support as the theater company’s official airline. Delta Airline’s defense is that the Public’s “artistic and creative direction crossed the line on the standards of good taste,” regardless of political preference. Distancing from the Public is understandable. Their fear of the implications of even being associated with the production is probably for nothing, however. By nature of having been in the pit, one way or another, someone will be calling for a boycott. However, Delta’s complete withdrawal seems rather over-reactive and reminiscent of the uninformed critical sentiment.

Good taste/bad taste

For me, I am usually quite insensitive to good taste/bad taste in art, as I admit that there is usually acceptable, albeit not necessarily agreeable, justification. However something that I do find in bad taste is the depiction of a murder of a living, non-fiction, human being. Although Eustis claims that the character is Julius Caesar, there is no denying the implications. I feel similarly, in the case of controversial 2014 film The Interview (although not actually a murder, but an assassination attempt on a living foreign leader).

Regardless, as an artist I must defend the freedom of expression, for I cannot fathom the pain of being censored myself. However, I don’t have to agree, and I have every right to debate it. An exception is if something has a realistic potential for inciting violence, which I do not believe is a concern here.

Other productions

In his interview with the Times, Eustis mentions a Obama-as-Caesar production of Julius Caesar directed by Rob Melrose in 2012. The production, Eustis asserts, was left untouched by the left.

"This is about the right-wing hate machine. Those thousands of people who are calling our corporate sponsors to complain about this — none of them have seen the show. They’re not interested in seeing the show. They haven’t read Julius Caesar. They are being manipulated by ‘Fox & Friends’ and other news sources, which are deliberately, for their own gain, trying to rile people up and turn them against an imagined enemy, which we are not.” --Oskar Eustis (The New York Times)

The Melrose production received $25,000 in funding from the NEA (Grant #12-3200-7004).

Following the line of articles regarding the Public’s production, the New York Times released an article about other Julius Caesar productions in history that have captured the story through the lens of the times.

“When Caesar is killed, it’s horrifying, it’s awful — whether it’s Obama or Trump. Trump, Republicans and Democrats should all take heart that what this play says is that killing a political leader, no matter how righteous your views are, is a bad idea — a terrible idea.” --Rob Melrose (New York Times)

Finally

I want to end this post with a final quote from Oskar Eustis. It transcends the politics of the controversy, and addresses a wider concern; a lesson from Julius Caesar.

“Act Three, Scene One of Shakespeare’s JULIUS CAESAR takes place on the Ides of March, 44 B.C.

By the time that scene is over, democracy will have vanished from the face of the earth for almost two millennia, until some English colonists on the eastern seaboard of North America start throwing tea into Boston Harbor.” --Oskar Eustis (Public Theater)

Whatever happens here, take care of your democracy. It’s fragile, and precious.

#trump#obama#politics#theatre#theater#shakespeare#julius caesar#caesar#nytimes#thepublic#arts#performing arts#freedom of expression#free speech#drama#current events#news#controversy#nea#english#literature

1 note

·

View note

Text

Causing a Rackett, part 1

Starting this past semester I have been researching a short-lived musical instrument called the rackett. My goal is to recreate a consort of racketts, as well as explore organology through 3D-printing.

About the rackett

The rackett is a double-reeded instrument (much like the bassoon) that existed from the late-Renaissance through the early-Baroque periods. Although the country of origin is unknown, racketts are likely German or Italian creations; the name stems from the German work for “crooked:” rankett. The instrument’s convoluted design and quiet projection mostly likely resulted in its demise, lasting less than 50 years on the timeline. But history has not forgotten them.

➜ Listen to David Munrow and members of the Early Music Consort perform on Renaissance racketts (Youtube)

The design

There are two types of rackett designs, the Renaissance and the Baroque. They differ in two ways. The Renaissance rackett is cylindrical bore, and uses a reed placed at the top with a pirouette. The Baroque design on the other hand is a composite conical bore (a series of ever growing, but not tapered cylindrical bores) and employs a bocal much like a bassoon’s. I will be focusing on the Renaissance design in my research.

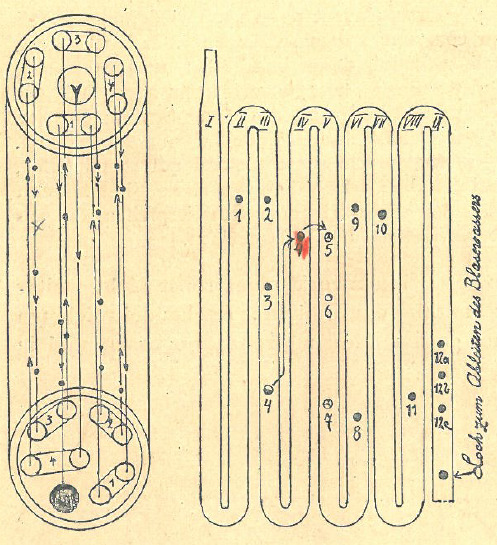

The rackett’s design is ingenious in a way; nine parallel bores are drilled into a cylinder and connected from alternatively top and bottom by carving through the end walls and sealing with cork plugs (Fig. 1). A double reed connects to the thin bores that run up and down the instrument, resulting in a deceivingly long instrument, and producing a low buzz. The discant rackett, smallest in the rackett family, is a 12 cm tall cylinder with a diameter of 4.8 cm. The small instrument packs over a meter of tubing (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1- A cutaway view of the bore system. The center bore goes down an connects to the bore on the right

Fig. 2- A sketch based on the Kunsthistoriche Museum’s discant rackett design

A pirouette is attached to the top of the instrument, from which half the reed protrudes (Fig. 4). The pirouette, in addition to being a very decorative part of the instrument, has a curious practical function. The rackett, being a low instrument, requires a very loose embouchure (lip pressure) in order to achieve low notes; too tight, and the instrument cannot reach the low notes. The problem with a loose embouchure on a free standing reed is that the player end up not having enough hold on the reed to keep it from sliding positions in the mouth. Thus a pirouette acts as a guard of sorts that the player’s mouth position can hold firm while maintaining a loose embouchure.

Fig. 3- A cutaway view of the pirouette and the reed within (the staple is also shown; the component that connects the reed and pirouette to the main body)

Racketts were made of boxwood or ivory; the only surviving originals (in Leipzig and Vienna) are made of the more durable ivory. The issue with racketts constructed from wood was the issue of moisture. The compact design of the instrument made it hard to wick out moisture. Consequently, cracks, rotting and even explosions were noted in the history books.

The sound

Because of the long tubing, the rackett family is a bass-y set of instruments. The discant rackett has a range of about G2 to D4. The tenor-alt, bass, and gross-bass (great bass) go even further down the bass range. Due to the small bore size however, (the discant’s bores are a mere 6mm in diameter) the instrument is considerable quieter than other reeded wind instruments (much like how the larger the bore of a tuba, the larger the sound, the small the bore, the quieter the sound). They emit a low buzzing timbre, much like the combination of a bassoon and a kazoo. Their unique timbre allows them to cut through large chamber ensembles.

➜ Compare the range and sound of a baroque contrabassoon and the great-bass rackett (Facebook, Unholy Rackett)

3D modeling

Following in the footsteps of Ricardo Simian and Jamie Savan and their work in 3D printing the Renaissance cornett, I decided to step up the game with a more complex instrument. I have been modeling using Autodesk Fusion 360 (See Fig. 4).

I have spent the last six days creating a digital replication of a Renaissance tenor-alt rackett based on published blueprints from the Toronto Consort Workshop publication of rackett-building instructions. Their design is modeled on the Leipzig original.

The first five days were spent creating the main model which consists of the body (main body, plugs, and end caps), the staple, the pirouette, and the reed (similar to a bassoon reed). The sixth day was spent redesigning the rackett for 3D printing.

Fig. 4- A wire-frame version of the rackett model in the Fusion 360 view-port

Preparing the 3D model for printing required changes to the design (I should note that all the parts, except the reed, will be 3D printed). As I will be using a Formlabs Form 1 SLA printer, I needed to adapt the model according to its restraints.

The Form 1 cannot print larger than a 125x125x165 mm object. Although the pirouette, staple, and reed are all separate from the body, and all much smaller than the maximum print size, the body itself is 200 mm long. To fix this, I basically chopped the rackett in two, combined the plugs and end caps with the body, and created a male-female design to minimize air leakage, especially from bore to another (Fig. 5). The advantage of this design, as far as I can tell, is that it will be easier for condensation to drip out of the instrument after use.

Fig. 5- A render of the components ready to be printed (plus the reed). Note that the top half of the body is upside-down to show the connection design. Starting from the left, counter clockwise: pirouette, top body, bottom body, staple, reed.

Hopefully, early into fall semester I can print this one out and give it a try! I’d like to print this in clear resin (Fig. 6); it’d either be really cool, or mildly cool and then eventually disgusting to look at.

Fig. 6- Render using transparent (in this case, polycarbonate) materials.

This is merely the beginning of this project, however. I intend to continue to work on it through the entire 2017-2018 academic year, culminating in a research paper, lecture/presentation/demonstration, and a consort concert.

Until part 2 (which will probably come much later),

A.

Thanks to: My project adviser Dr. Sarah Waltz, outgoing Powell Scholars Director Dr. Cynthia Wagner-Weick, the Powell Scholars Program, and the University of the Pacific. Also thanks to Gregor for introducing me to this monstrosity of an instrument.

Additional resources

Kite-Powell, Jeffery T. “Racket.” A Performer’s Guide to Renaissance Music. New York: Schirmer, 1994. 76-78. Print. A short but detailed profile of the rackett, as well as some pointers on playing the instrument.

Robinson, Trevor. “Racketts.” The Amateur Wind Instrument Maker. Amherst: U of Massachusetts, 1973. 71-75. Print. Robinson provides some basic information about the rackett, as well as a modified (in some ways simplified) rackett design accessible to hobbyists. The book includes blueprints and finger-hole measurements. Additionally, the rest of the book is an intriguing resource, covering several other instruments as well.

#music#renaissance#instrument#3d modeling#3d printing#engineering#technology#university of the pacific#history#music history#formlabs#autodesk#classical music#conservatory#research#academia#university

10 notes

·

View notes

Audio

This is a pretty crappy recording of a crappy reading, but it’s better than nothing... My final project for Adv. Orchestration!

2 notes

·

View notes