#Ælfgifu

Text

If the English and British consorts had regnal numbers

#i decided not to include the ones where there’s only one consort with that name#since they wouldn’t have a number#Ælfgifu of shaftesbury#Ælfgifu#Ælfgifu of york#ealdgyth#edith of wessex#edith of mercia#matilda of flanders#matilda of scotland#matilda of boulogne#eleanor of aquitaine#isabella of angoulême#eleanor of provence#eleanor of castile#margaret of france#isabella of france#anne of bohemia#isabella of valois#catherine of valois#margaret of anjou#elizabeth woodville#anne neville#elizabeth of york#catherine of aragon#anne boleyn#anne of cleves#katherine howard#katherine parr#phillip ii

135 notes

·

View notes

Text

---

#shes canon except her appearance#I wonder if Emma will be mention tooo#Likeeeeeeeee#Plsssssss#vinland saga#vinland fanart#prince canute#Ælfgifu

20 notes

·

View notes

Link

“Ælfgifu and Swein ruled Norway for four years. This period became known as ‘Alviva’s time’, and she gained a reputation as tyrannical ruler who taxed the population heavily, causing the Norwegians to rebel against her. Ælfgifu and Swein were driven out, with Swein dying soon after in Denmark.

Ælfgifu made it back to England, however, around the time that Cnut died in 1035. This was advantageous for her, as it allowed her to participate in the ensuing succession dispute and act on behalf of her living son Harald. Succession disputes were arenas in which mothers could exert a great deal of influence, and in turn face harsh defamation.

(...)

Ælfgifu’s fate is unknown after fortunes turned against her. Her reputation was in tatters in both Norway and England. It was during Harthacnut’s reign that Emma had a literary work written about the events since the Danish conquest, a work which has been named the Encomium Emmae Reginae. A political justification of Emma’s actions lies behind every word. Its narrative casts aspersions on the parentage of the late King Harald, stating that Ælfgifu was a mere concubine, and that Harald was secretly the child of a servant placed into her bed. It even implicates Ælfgifu in the murder of one of Emma’s sons from her marriage to Æthelred.

All evidence indicates that these accusations do not reflect reality - but unlike Emma, Ælfgifu seemingly did not get chance to produce a work telling her side of events. Because of this, the formidable Emma is the more famous queen, while Ælfgifu has been sidelined in history. That does not mean Ælfgifu was not a rival for Emma, and every bit her match.”

#history#women in history#norway#england#english history#Ælfgifu of Northampton#queens#female rulers#11th century#middle ages#medieval women#medieval history#Emma of normandy

47 notes

·

View notes

Video

Special thanks to @darkrainbowtear

#vinland saga#canute#prologue arc#slave arc#prince canute#bretwalda canute#king canute#thorfinn#ragnar#gratianus#emma of normandy#snake#fox#badger#willibald#edmund ironside#einar#Ælfgifu of Northampton#ulf#Christian God maybe#bisexual#animatic

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#vikings valhalla#vikings: valhalla#vikingsvalhallaedit#perioddramaedit#pollyanna mcintosh#Ælfgifu of norhhampton#aelfgifu of northampton#my edits#stills

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dream 😍

#tw ed diet#tw ana shit#ed but not sheeran#tw ana diary#b1nge eating#ed relapse#ed account#tw ana relapse#ðšð¾ð»ñœñð°ð¹#disordered eating thoughts#disordered eating in tags#anor3x14#¾#ælfgifu of northampton

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

-`Æð𝒆𝒍𝒔𝒕𝒂𝒏 𝒂𝒏𝒅 Æ𝒍𝒇𝒈𝒊𝒇𝒖, 𝒕𝒉𝒆 𝒇𝒊𝒓𝒔𝒕 𝒓𝒆𝒄𝒐𝒓𝒅𝒆𝒅 𝑺𝒐𝒎𝒆𝒓𝒔𝒆𝒕𝒔´-

Born at the thriving age of the Anglo-Saxon dynasty in England, Ædestan was the son of an unknown but wealthy and important land of Mercia, meanwhile Ælfgifu, named after the Queen, was the epitome of the perfect Saxon noblewoman, who was also an incredible warrior on her own right.

Both of them fell in love during the constant wars, when Ælfgifu mistook Ædestan for a soldier and, when pinned down with a sword to his throat and a witty and flirty remark of him, the two connected after fending off the enemies and patching each other's wounds, they courted and, after the war was over, married on a great ceremony that was even attended by the King and his Queen.

The two of them would get on to have fifteen children, though only six would survive adulthood. The daughters married onto the nobility across what would later be England and the sons made equally auspicious matches that would mark them in history as one of the oldest families to remain in England, thing they'd remind on their family motto

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ages of English Queens at First Marriage

I have only included women whose birth dates and dates of marriage are known within at least 1-2 years, therefore, this is not a comprehensive list. For this reason, women such as Philippa of Hainault and Anne Boleyn have been omitted.

This list is composed of Queens of England when it was a sovereign state, prior to the Acts of Union in 1707. Using the youngest possible age for each woman, the average age at first marriage was 17.

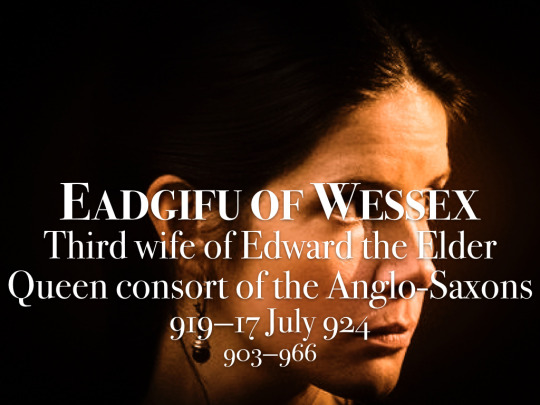

Eadgifu (Edgiva/Ediva) of Kent, third and final wife of Edward the Elder: age 17 when she married in 919 CE

Ælfthryth (Alfrida/Elfrida), second wife of Edgar the Peaceful: age 19/20 when she married in 964/965 CE

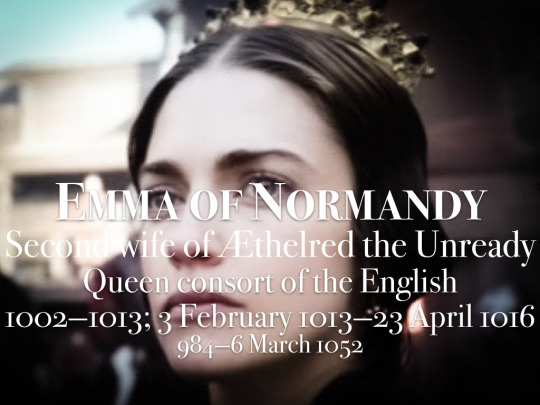

Emma of Normandy, second wife of Æthelred the Unready: age 18 when she married in 1002 CE

Ælfgifu of Northampton, first wife of Cnut the Great: age 23/24 when she married in 1013/1014 CE

Edith of Wessex, wife of Edward the Confessor: age 20 when she married in 1045 CE

Matilda of Flanders, wife of William the Conqueror: age 20/21 when she married in 1031/1032 CE

Matilda of Scotland, first wife of Henry I: age 20 when she married in 1100 CE

Adeliza of Louvain, second wife of Henry I: age 18 when she married in 1121 CE

Matilda of Boulogne, wife of Stephen: age 20 when she married in 1125 CE

Empress Matilda, wife of Henry V, HRE, and later Geoffrey V of Anjou: age 12 when she married Henry in 1114 CE

Eleanor of Aquitaine, first wife of Louis VII of France and later Henry II of England: age 15 when she married Louis in 1137 CE

Isabella of Gloucester, first wife of John Lackland: age 15/16 when she married John in 1189 CE

Isabella of Angoulême, second wife of John Lackland: between the ages of 12-14 when she married John in 1200 CE

Eleanor of Provence, wife of Henry III: age 13 when she married Henry in 1236 CE

Eleanor of Castile, first wife of Edward I: age 13 when she married Edward in 1254 CE

Margaret of France, second wife of Edward I: age 20 when she married Edward in 1299 CE

Isabella of France, wife of Edward II: age 13 when she married Edward in 1308 CE

Anne of Bohemia, first wife of Richard II: age 16 when she married Richard in 1382 CE

Isabella of Valois, second wife of Richard II: age 6 when she married Richard in 1396 CE

Joanna of Navarre, wife of John IV of Brittany, second wife of Henry IV: age 18 when she married John in 1386 CE

Catherine of Valois, wife of Henry V: age 19 when she married Henry in 1420 CE

Margaret of Anjou, wife of Henry VI: age 15 when she married Henry in 1445 CE

Elizabeth Woodville, wife of Sir John Grey and later Edward IV: age 15 when she married John in 1452 CE

Anne Neville, wife of Edward of Lancaster and later Richard III: age 14 when she married Edward in 1470 CE

Elizabeth of York, wife of Henry VII: age 20 when she married Henry in 1486 CE

Catherine of Aragon, wife of Arthur Tudor and later Henry VIII: age 15 when she married Arthur in 1501 CE

Jane Seymour, third wife of Henry VIII: age 24 when she married Henry in 1536 CE

Anne of Cleves, fourth wife of Henry VIII: age 25 when she married Henry in 1540 CE

Catherine Howard, fifth wife of Henry VIII: age 17 when she married Henry in 1540 CE

Jane Grey, wife of Guildford Dudley: age 16/17 when she married Guildford in 1553 CE

Mary I, wife of Philip II of Spain: age 38 when she married Philip in 1554 CE

Anne of Denmark, wife of James VI & I: age 15 when she married James in 1589 CE

Henrietta Maria of France, wife of Charles I: age 16 when she married Charles in 1625 CE

Catherine of Braganza, wife of Charles II: age 24 when she married Charles in 1662 CE

Anne Hyde, first wife of James II & VII: age 23 when she married James in 1660 CE

Mary of Modena, second wife of James II & VII: age 15 when she married James in 1673 CE

Mary II of England, wife of William III: age 15 when she married William in 1677 CE

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

I love the GoT series, especially for its historical accuracies (I could talk about them for daaaaaays), but I get really annoyed with the age gap debate with ships without taking into account the historical setting (especially Sansa Stark and Sandor Clegane). this has annoyed me to the point where I am writing a book to address the social construct just to tear it down.

In the past noble girls were married early. Not usually as soon as they had their first period (although legal), this was usually delayed until 16-18 years due to negotiations (it was a trade deal). However, most nobles would be married before they turned 20, unless they were undesirable for some reason (this could be appearance, family scandal, illness, physical health, disability, or personality), and they would quickly become known as spinsters - we think of spinsters being unmarried woman past middle age, but in the past, this could be used for an unmarried 25 y/o. Reminder that 'paedophile' refers to the attraction of prepubescent children (by UK law this is under 13).

Women married early for biological reasons; they have a short fertility period (while some men can keep fathering sons for decades; think Walder Frey). From first blood to menopause, a woman had to be married off as quickly as possible to ensure they had the best chance of providing as many children as possible. Menopause is currently between 45-50 yrs (with some biological variation), but in the past, this could be as early as 35 - unclear due to natural variation, but health and hygiene contribute to fertile health and the decline would be noted as the end for many noble women.

Men sometimes married later, usually for education, status, or military reasons. So one could expect a man not to marry until in their 20s (of higher social standing). Commoners skew the statistics, as they would marry at any age, and usually more love-matches (no need for social staus debates and political marriages), however, common men would be expected to have a job in order to provide for a wife and family, and so would sometimes be older, but the

If a man needed a wife, say windowed at 30. Guess what, they'd start at the beginning looking for a teenager. There was no point marrying an older woman (if there were any that were unmarried, that is). Widows were often off the cards if they had children as they would still belong to their dead spouse's family, and the social 'undesirables' would still be undesired by a man seeking their second or third wife. For example, Æthelred the Unready first married Ælfgifu - she was 4 years younger and perfectly normal. She died aged 32. His second wife Emma, was 18 years younger (aged 18 at the time) - a much larger age gap and unseemly by modern standards, but Æthelred would not have married a woman in her 30s whose fertility could decline shortly after marriage simply to marry someone closer to his own age.

Childhood and teenagers are relatively new terms. In the past, they were better defined as prepubescent and of marital age (postpubescent). Meaning you were considered almost adult once you could reproduce. To view historical fiction by modern standards, laws, and norms, is a mistake. One should understand the history to better understand the subject material and fictional writings it has inspired.

The best way to understand this is to understand why marriage was invented: to produce legitimate heirs. This is why infidelity was viewed differently for men and women - a man is unfaithful, it is a distraction and a sin, but bastards have no claim. A woman is unfaithful, this brings into question the legitimacy of her existing children, and she has wasted almost a year providing someone else a child. Not such a big deal now, but childbirth was also dangerous; they could literally die due to an affair... even before the husband found out about it. Therefore, ensuring the bride had enough time to produce children was essential. Bear in mind that during the Middle Ages, one could get an annulment for infertility in many countries (and still can) - as this is a breach of the marriage contract.

P.S. - This is historical thinking. I am pro same-sex marriage and believe this should have been legalised when marriage changed the definition to a declaration of love (circa 18th century)... but that's a religious debate for another time.

Back to the topic; Sansa Stark would not see age as an issue really. Although she hoped for a love match (and thus naturally inclined to someone near her own age), socially, she would see nothing wrong with Sandor Clegane based on age. Clegane would have had issues with any attraction until she reached 'adulthood' (before her first period) as this would have been considered immoral, however, once deemed an adult, this no longer poses an issue legally. Lysa was 21 years younger than Jon when they married - she protested this based on age, but realistically she only protested as she had hoped to marry Petyr.

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

I got curious and decided to check who Canute’s wives were, because they are most likely canon since it’s historical facts.

So there’s his first wife, Ælfgifu, and then there’s his second wife, Emma.

Emma is interesting, because her first husband was Ethelred… yes, that Ethelred, king of England.

Canute really had the man murdered and then he married his widow!

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Thing Of Vikings Chapter 73: Harthacnut Is Better Than None

Chapter 73: Harthacnut Is Better Than None

Harthacnut (Danish: Hardeknud), occasionally named as Canute III, was King of Denmark from AD 1035 to AD 1042, and King of England from AD 1040 to AD 1042. The son of King Canute the Great and Emma of Normandy, he was born, in July 1017, in England, shortly after their marriage. As part of the negotiations of surrender in the aftermath of King Canute's conquest of England, Harthacnut took precedence in inheritance over his older half-brothers from his parents' first marriages. When their father died in AD 1035, Harthacnut was left ruling Denmark, while his half-brother Svein (son of Ælfgifu of Northampton) was faced with a revolt in Norway, and Harold Harefoot (also son of Ælfgifu) took control in England.

[...]popularly seen as little more than a brutal tyrant without virtue or redeeming value, Harthacnut has usually been presented in a highly moralistic fashion in most popular media over the centuries. In these stories, he is used as an archetypal figure of the corrupt and brutal nobleman whose own evils bring about his downfall, an almost idealized villainous figure from whose tyranny and grotesque abuses the populace are freed from.

As such, in contemporary media, there is little interest in conflicting perspectives on his family background and upbringing that produced him. This is not helped by the recorded accounts of his actions, including massacres, repressive taxation, executions, feasts in the midst of bad harvests, oathbreaking, violations of hospitality, loyalty purges, and even the posthumous beheading and disposal of Harold Harefoot, his paternal half-brother, in retribution for the death of Ælfred Æþeling, Harthacnut's maternal half-brother. His death on 11 June, AD 1042 is seen as appropriately fated, but even then, he is typically overshadowed by the other events of the day...

—Dragons of the North: Profiles Of The Viking Lords, Waterford University Press, 1733

AO3 Chapter Link

~~~

My Original Fiction | Original Fiction Patreon

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Consorts of England and Britain

House of Wessex

#consorts of england and britain#ealhswith#Ælfflæd#eadgifu of kent#Ælfgifu of shaftesbury#Æthelflæd of damerham#Ælfgifu#Ælfthryth#Ælfgifu of york#emma of normandy#ealdgyth#edith of wessex

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Pollyanna McIntosh in Vikings: Valhalla (s1-s2) as Queen Ælfgifu

#pollyanna mcintosh avatars#vikingsedit#vikingsvalhallaedit#period fc#pollyannamcintoshedit#queen aelfgifu#aelfgifu of northampton#pollyanna mcintosh#vikings valhalla#rp avatars#avatars 400*640#rpg resource#*avatars#*mine

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Bastard Kings and their families

This is series of posts are complementary to this historical parallels post from the JON SNOW FORTNIGHT EVENT, and it's purpouse to discover the lives of medieval bastard kings, and the following posts are meant to collect portraits of those kings and their close relatives.

In many cases it's difficult to find contemporary art of their period, so some of the portrayals are subsequent.

1) Aethelstan I of England (894 – 939), son of Edward the Elder and his wife Ecgwynn

2) Edward the Elder (c. 874 –924), son of Alfred the Great and his wife Ealhswith

3) Æthelflæd of Mercia (c. 870 – 918), daughter of Alfred the Great and his wife Ealhswith

4) Eadgifu of Wessex (? - c. 951), daughter of Edward the Elder and his wife Ælfflæd; and her son with Charles III of France, Louis IV of France (920/921 – 954)

5) Edmund I of England (920/921 – 946), son of Edward the Elder and his wife Eadgifu of Kent

6) Eadwig I "All-Fair" of England (c. 940 – 959), son of Edmund I of England and his wife Ælfgifu of Shaftesbury

7) Edgar I of England (944 – 975), son of Edmund I of England and his wife Ælfgifu of Shaftesbury

8) Eadred I of England (c. 923 – 955), son of Edward the Elder and his wife Eadgifu of Kent

9) Eadburh of Winchester (921/924-951/953), daughter of Edward the Elder and his wife Eadgifu of Kent

10) Eadgyth of England (910–946), daughter of Edward the Elder and his wife Ælfflæd

#jonsnowfortnightevent2023#canonjonsnow#day 10#echoes of the past#asoiaf#a song of ice and fire#historical parallels#medieval bastard kings#bastard kings and their families#aethelstan i of england#aethelstan of england#edward the elder#Æthelflæd#Lady of the Mercians#Eadgifu of Wessex#Louis IV of France#Edith of England#Eadred of England#Edmund I of England#Eadburh of Winchester#Eadwig All-Fair#Edgar of England#aethelflaed of mercia

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

MEDIEVAL WOMEN AS PROVIDERS OF HEALTH CARE

“...While a formal education in medicine was the preserve of men in the Middle Ages, and women were not licensed, not all medical practitioners were academically trained and Green warns rightly against only recognising the activities of ‘explicitly labelled practitioners’. In England, an example of a woman saint being described as ‘benedicta medica’ [the blessed doctor] can be found in Goscelin of St Bertin’s late eleventh-century account of the visionary healing from scrofula of Ælfgifu, abbess of Wilton, by the royal saint Edith of Wilton (d. c. 986).

However this is a posthumous miracle, and Goscelin does not attribute the title or similar healing activities to Edith in his earlier narrative of her life. Nevertheless, even if women medical practitioners were seldom formally recognised in such terms, women did contribute to scholarly discourse on medicine.

While the attribution of women’s health care texts to the putative female physician Trotula of Salerno is problematic, the abbess and visionary Hildegard of Bingen is famous for two medical works: an encyclopaedia of the natural world, Physica, which includes an extensive herbarium, or description of the medicinal properties of plants; and her compilation of medical advice, Causae et Curae.

The twelfth century however seems to have been exceptional in this respect, and according to Green in Making Women’s Medicine Masculine, women’s engagement with medical textual culture declined in the later Middle Ages, and their access to handbooks on healthcare was severely limited. While some exceptional women, including the mid fourteenth-century Cecilia of Oxford, employed by Philippa of Hainault, wife of Edward III, even practised as surgeons, most engaged in a range of medical practices that were not identified in professional terms, including midwifery, wet nursing and nursing.

…Margery Kempe provides a particularly interesting, and potentially anomalous or atypical, example of the sort of expectations that circulated around female involvement in health care in late medieval England, because although Kempe was a married laywoman, she had a conversion experience as an adult, and thereafter lived a deeply religious life, which was expressed in her distinctive dress, her diet, her frequent pilgrimages, her prayers and her visions and affective piety.

In this respect, and similar to vowesses, beguines and lay anchoresses, Kempe blurs the boundary between the laywoman and the woman religious. Her Book records in considerable detail the hostility that her unconventional religious life generated, and her treatment of her husband is no exception. When the increasing frail John Kempe fell down stairs, his wife was blamed for neglecting him and thus for failing in her duties: ‘And þan þe pepil seyd, ȝyf he deyd [died], hys wyfe was worthy to ben hangyn for hys deth, for-as-meche as sche myth a kept hym & dede not.’

Kempe represents caring for her senile husband – in typical effective detail – not as a vocation, but as an act of penance, but the reality must have been that nursing was a key element of medieval housewifery, and that fulfilling this role was expected of women. Women within the household also engaged in practices sometimes termed unlearned or popular, such as herbalism. Indeed, as we will see later in this article in the examples found in the Paston letters, the kitchen garden or herber was a major source of supplies for medieval medical treatments.

In late medieval England, hospitals were usually housed in or linked to religious houses, and looking after those who were ill or dying was seen as a particular vocation for nuns as well as for laywomen who served as hospital nurses. In the late thirteenth-century Golden Legend, St Elizabeth of Hungary is represented as exemplary in this respect. We are told that, following the death of her husband, she founded a hospital and took it upon herself to tend to the patients.

William Caxton’s 1483 English translation of this text is particularly illuminating: And then this blessed Elizabeth received the habit of religion and put herself diligently to the works of mercy, for she received for her dower two hundred marks, whereof she gave a part to poor people, and of that other part she made a hospital, and therefore she was called a wasteress and a fool, which all she suffered joyously.

And when she had made this hospital she became herself as an humble chamberer in the service of the poor people, and she bare her so humbly in that service, that by night she bare the sick men between her arms for to let them do their necessities, and brought them again, and made clean their clothes and sheets that were foul. She brought the mesels [lepers] abed, and washed their sores and did all that longed to a hospitaller.

Like every hagiography, the life of Elizabeth of Hungary is highly conventional, and the extreme virtue of the subject is inevitably described in stereotypical terms, yet this passage has a verisimilitude that gives the account some plausibility. There is no suggestion here that Elizabeth miraculously healed all who came to her – the miracle, in so far as there is one, lies in the fact that the saint, who was born a princess, in her humility willingly embraces menial tasks, and endures the scorn of her critics.

Caxton’s choice of language is revealing: Elizabeth is a ‘chamberer’—that is, a ‘servant’ – but she is also a ‘hospitaller’, in other words a religious dedicated to the care of the sick. However, the word ‘hospiteler’ or ‘hospitaller’ usually referred specifically to the Knights Hospitaller, the male religious and chivalric order that has its origins in caring for sick pilgrims in the Holy Lands.

In translating this text for an English audience in the fifteenth century, Caxton seems to have been uncomfortable with the saint undermining her own aristocratic status, and in referring to her as a ‘hospitaller’ Caxton elevates her role significantly above that of a servant or nurse, and in so doing genders her role masculine. Because care for the body and care for the soul were seen to be inextricably linked, the practices of medicine and religion were entwined.

From the early medieval period onwards, physical illness was often associated with sinfulness, as seen in the following passage, describing the death of the saintly Anglo-Saxon abbess Æthelthryth of Ely in the seventh century, from Bede’s Ecclesiastical History (completed 731): [But more certain proof is given by a doctor named Cynefrith, who was present at her [Æthelthryth’s] death-bed and at her elevation from the tomb. He used to relate how, during her illness, she had a very large tumour beneath her jaw.

‘I was ordered’, he said, ‘to cut this tumour so as to drain out the poisonous matter within it. After I had done this she seemed to be easier for about two days and many thought that she would recover from her sickness. But on the third day she was attacked by her former pains and was soon taken from the world, exchanging pain and death for everlasting health and life. …’

It is also related that when she was afflicted with this tumour and by the pain in her neck and jaw, she gladly welcomed the said pain and used to say, ‘I know well enough that I deserve to bear the weight of this affliction in my neck, for I remember that when I was a young girl I used to wear an unnecessary weight of necklaces; I believe that God in His goodness would have me endure this pain in my neck in order that I may thus be absolved from the guilt of my needless vanity. So, instead of gold and pearls, a fiery red tumour now stands out upon my neck.’]

Whereas for Margery Kempe in the fifteenth century the task of nursing is

the act of penance, for Æthelthryth in the seventh century, the tumour itself is a physical sign of former sin, and the patient endurance of this plague is an act of atonement. However Bede’s account is more multilayered than this analysis suggests. As Bede’s life of Æthelthryth recounts, the abbess had been twice married before becoming a nun.

While Bede insists that Æthelthryth’s marriages were unconsummated, his narrative betrays anxiety about her status as a virgin, which is only resolved when her body is exhumed in order to be moved to another burial site, and found to be uncorrupted – with the wound on her neck where the tumour was removed miraculously healed, and only a faint scar remaining.

For the physician Cynefrith, and for Bede himself, the evidence of the uncorrupted corpse was proof that Æthelthryth remained pure in her lifetime, but the scar, as a reminder of the suffering caused by her tumour, indicates that by the time of her death Æthelthryth had fully atoned for her former imperfections, which include her marriages as well as her vanity.

While physical illnesses were often, although not necessarily, linked to sinfulness, mental illness in particular was associated with possession by devils. Treatment of both therefore might be directed at the soul as well as the body or the mind and, alongside prayer, charms, incantations and invocations were used for healing. Prayers to Christ and the saints, including the Virgin Mary, were seen to be particularly effective, and might be combined with other devotional acts such as pilgrimage.

…By the Reformation the Shrine of Our Lady at Walsingham in Norfolk, which was founded in the eleventh century, was one of the most important pilgrimage destinations not only in England, but in Western Christendom. The fame and significance of the shrine served to reinforce the reputation of the Virgin Mary, if not as physician, then certainly as intercessory healer.”

- Diane Watt, Medicine, Religion and Gender in Medieval Culture

#medicine#religion#gender#medieval#history#diane watt#medicine religion and gender in medieval culture

50 notes

·

View notes