#Armistice of 11 November 1918

Text

During the First World War, Queen Mary (26 May 1867 – 24 March 1953) paid her respects in 1916 at local memorial shrines in East London.

The ‘Roll of Honour’ (seen in the second photograph) listed over 100 men from around this street in Hackney who had enlisted.

#Queen Mary#British Royal Family#Remembrance Day#World War I#1900s#Roll of Honour#Royal Collection Trust#Poppy Day#Armistice of 11 November 1918#poppies#East London#20th century#war#Armistice Day#memorial day

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

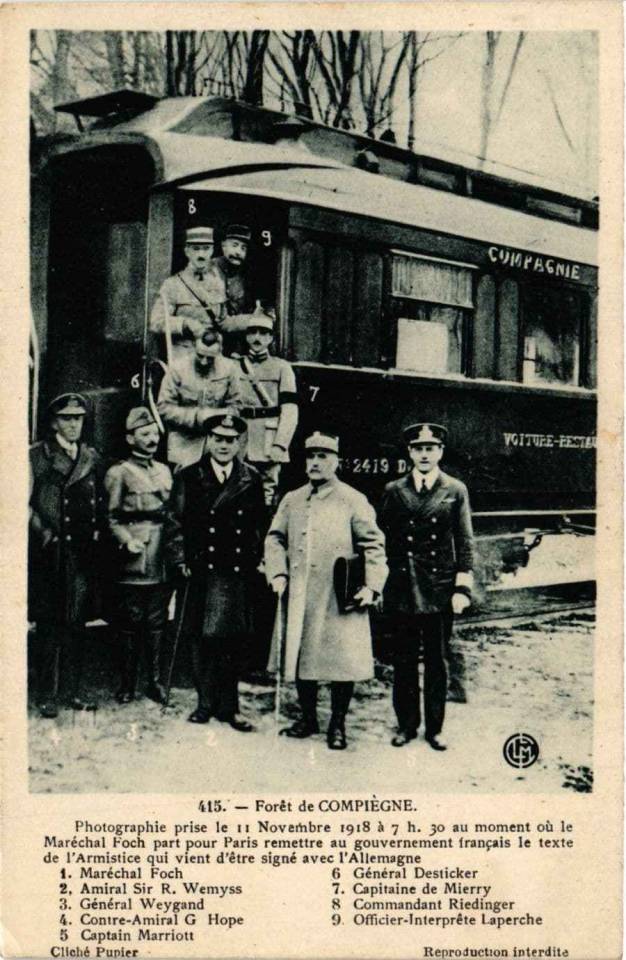

Armistice of 11 November 1918, signed in a wagon in Le Francport, Picardy region of France

French vintage postcard

#vintage#francport#picardy#armistice#wagon#tarjeta#france#briefkaart#postcard#photography#11 november 1918#region#postal#carte postale#sepia#ephemera#historic#french#ansichtskarte#1918#postkarte#le francport#november#signed#postkaart#photo

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

' ..and from the ground there blossoms red, life that shall endless be. '

#Flanders Fields#Remembrance Day#armistice#poppy field#WWI#11 November 1918#Belgium#We will remember them

138 notes

·

View notes

Photo

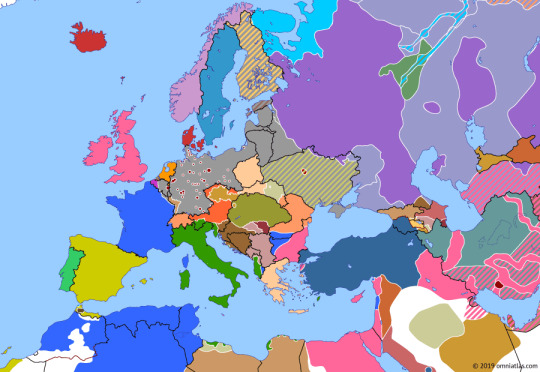

Germany and Austria in 1925

« Atlas des peuples d’Europe occidentale », Jean et André Sellier, La Découverte, 1995

by cartesdhistoire

From the summer of 1918, the German offensive in the West was an absolute failure. However, in Berlin, civil authorities continued to believe that Germany had the upper hand. On October 2, the General Staff informed the parties in the Reichstag of the urgent need to end the fighting swiftly, as the situation risked deteriorating decisively. The parliamentarians were shocked and dismayed. At 5 a.m. on November 11, the armistice was signed in Rethondes.

Yet, the Germans did not tangibly feel their defeat or experience it in their daily lives, except in the Rhineland. The country remained physically intact, its infrastructure undamaged, and no decisive battle led to the rout of the German army. The victory on the Eastern Front was also significant. The General Staff managed to conceal the army's disintegration by repatriating regiments in good order whenever possible, to the cheers of the crowds. Consequently, defeat for the Germans became an abstract notion that could be denied. How could a stable peace be established with a defeated opponent who refused to acknowledge their defeat?

Pétain and Pershing, the commander of the American Expeditionary Force, had initially wanted to continue the Allied offensive against a crumbling German army and advance to the Rhine to make the Germans understand and admit the extent of their defeat. However, after four years of war, this proved to be politically and morally impossible, a fact that Clemenceau and Foch fully understood.

The Treaty of Versailles, signed on June 28, was the best possible outcome at the time of its negotiation. However, it also sparked controversy among the victorious camp when Keynes published "The Economic Consequences of the Peace." This book, which became immensely popular, was used in Germany to justify opposition to the treaty and simultaneously created a myth in Anglo-Saxon countries that Germany was being unfairly treated.

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

November 11, 1918. Headline: Armistice Signed War Ends at Six. What a happy day that must have been. From Kenneth McIntyre, FB.

160 notes

·

View notes

Text

11 November 1918

A group of American soldiers ride in a truck, waving American flags during an Armistice Day parade , New York City. One soldier holds a sign reading 'To Hell With The Kaiser.'

(Colour by RJM)

#the great war#historical photos#world war 1#wwi#world war one#the first world war#history#ww1#canadian history#1917

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Armistice Day 11 November 1918

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the Air by Christopher Nevinson, 1917. Lithograph.

Today is Armistice Day, commemorated every year on 11 November to mark the end of the First World War and the armistice signed.

In this work by Christopher Nevinson the abstract patchwork of fields is laid out under the wing of a military aircraft, the sharp angles of the composition emphasising the dizzying height of the plane. During the war, the world was being seen from entirely new angles, inspiring artists to experiment and to depict landscape in new, unexpected ways.

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

November 11, 2023

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

NOV 12, 2023

In 1918, at the end of four years of World War I’s devastation, leaders negotiated for the guns in Europe to fall silent once and for all on the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month. It was not technically the end of the war, which came with the Treaty of Versailles. Leaders signed that treaty on June 28, 1919, five years to the day after the assassination of Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand set off the conflict. But the armistice declared on November 11 held, and Armistice Day became popularly known as the day “The Great War,” which killed at least 40 million people, ended.

In November 1919, President Woodrow Wilson commemorated Armistice Day, saying that Americans would reflect on the anniversary of the armistice “with solemn pride in the heroism of those who died in the country’s service and with gratitude for the victory, both because of the thing from which it has freed us and because of the opportunity it has given America to show her sympathy with peace and justice in the councils of the nations…."

But Wilson was disappointed that the soldiers’ sacrifices had not changed the nation’s approach to international affairs. The Senate, under the leadership of Republican Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts—who had been determined to weaken Wilson as soon as the imperatives of the war had fallen away—refused to permit the United States to join the League of Nations, Wilson’s brainchild: a forum for countries to work out their differences with diplomacy, rather than resorting to bloodshed.

On November 10, 1923, just four years after he had established Armistice Day, former President Wilson spoke to the American people over the new medium of radio, giving the nation’s first live, nationwide broadcast.

“The anniversary of Armistice Day should stir us to a great exaltation of spirit,” he said, as Americans remembered that it was their example that had “by those early days of that never to be forgotten November, lifted the nations of the world to the lofty levels of vision and achievement upon which the great war for democracy and right was fought and won.”

But he lamented “the shameful fact that when victory was won,…chiefly by the indomitable spirit and ungrudging sacrifices of our own incomparable soldiers[,] we turned our backs upon our associates and refused to bear any responsible part in the administration of peace, or the firm and permanent establishment of the results of the war—won at so terrible a cost of life and treasure—and withdrew into a sullen and selfish isolation which is deeply ignoble because manifestly cowardly and dishonorable.”

Wilson said that a return to engagement with international affairs was “inevitable”; the U.S. eventually would have to take up its “true part in the affairs of the world.”

Congress didn’t want to hear it. In 1926 it passed a resolution noting that since November 11, 1918, “marked the cessation of the most destructive, sanguinary, and far reaching war in human annals and the resumption by the people of the United States of peaceful relations with other nations, which we hope may never again be severed,” the anniversary of that date “should be commemorated with thanksgiving and prayer and exercises designed to perpetuate peace through good will and mutual understanding between nations.”

In 1938, Congress made November 11 a legal holiday to be dedicated to world peace.

But neither the “war to end all wars” nor the commemorations of it, ended war.

Just three years after Congress made Armistice Day a holiday for peace, American armed forces were fighting a second world war, even more devastating than the first. The carnage of World War II gave power to the idea of trying to stop wars by establishing a rules-based international order. Rather than trying to push their own boundaries and interests whenever they could gain advantage, countries agreed to abide by a series of rules that promoted peace, economic cooperation, and security.

The new international system provided forums for countries to discuss their differences—like the United Nations, founded in 1945—and mechanisms for them to protect each other, like the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), established in 1949, which has a mutual defense pact that says any attack on a NATO country will be considered an attack on all of them.

In the years since, those agreements multiplied and were deepened and broadened to include more countries and more ties. While the U.S. and other countries sometimes fail to honor them, their central theory remains important: no country should be able to attack a neighbor, slaughter its people, and steal its lands at will. This concept preserved decades of relative peace compared to the horrors of the early twentieth century, but it is a concept that is currently under attack as autocrats increasingly reject the idea of a rules-based international order and claim the right to act however they wish.

In 1954, to honor the armed forces of wars after World War I, Congress amended the law creating Armistice Day by striking out the word “armistice” and putting “veterans” in its place. President Dwight D. Eisenhower, himself a veteran who had served as the supreme commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force in Europe and who had become a five-star general of the Army before his political career, later issued a proclamation asking Americans to observe Veterans Day:

“[L]et us solemnly remember the sacrifices of all those who fought so valiantly, on the seas, in the air, and on foreign shores, to preserve our heritage of freedom, and let us reconsecrate ourselves to the task of promoting an enduring peace so that their efforts shall not have been in vain.”

—

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

#first world war#armistice#Letters From An American#Heather Cox Richardson#Dwight D. Eisenhower#war#peace#war and peace#soldier#soldiers#veterans#history#WWI#WWII

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Veterans Day, Victory Day and Duckvember - Cowardly Duck (Ducks)

Happy Armistice Day, Veterans Day and Victory Day!

Although I am late, I should still say that on November 11, 1918, the First World War ended and that day is commemorated for all soldiers who died in wars. Glory to them and peace to their souls! Amen.

Regarding that day, I drew two drawings that symbolize that day. The first drawing I drew is of Scrooge McDuck (in a Scottish military uniform) and Flintheart Glomgold (he is in a Boer (South African) military uniform) fighting under the flag of Great Britain (United Kingdom) on the Western Front against German soldiers (that what is in front of them is a German eagle in a military uniform). Yes, in my headcanon I believe that Scrooge and Glomgold were friends and fought together only in the First World War, which they won.

The second drawing I drew was a crossover of Three Caballeros and Looney Tunes and it was related to World War II. He found inspiration in the classic shorts "Daffy the Commando" (from 1943), "Commando Duck" (from 1944) and "Plane Daffy" (from 1944). Donald Duck (in US military uniform), Jose Carioca (in Brazilian military uniform), Panchito Pistoles (in Mexican military uniform) and Daffy Duck (as a pilot) fight together against Von Vulture, Baron von Sheldgoose (both German generals) and Hatta Mari (spy for the Third Reich). Yes, this is also the theme for Duckvember Cowardly Ducks in which Donald and Daffy are afraid of their enemies, yet all together they will defeat the three that make up the German Reich, and the Allies ended up defeating the Nazis in the war. I used a little bit from propaganda cartoons. I apologize to the Germans if they find themselves offended by this, these are just funny drawings. And no, I am not propagating anyone's propaganda, especially the ideology of the Third Reich, which I hate. Yes, even with uniforms and weapons, I'm still trying to draw. And that this song inspired me for these drawings: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5mt4B5Z8uLA

I hope you like these drawings and Happy Veterans Day, Armistice Day and World War I Victory Day once again.

#my fanarts#crossover#veterans day#duckvember#duckverse#looney tunes#three caballeros#scrooge mcduck#ww1#ww2#donald duck#flintheart glomgold#daffy duck#jose carioca#ducktales#panchito pistoles#disney#warner bros#duck comics#baron von sheldgoose#von vulture#hatta mari#army#history#comics#cartoons#germany#united kingdom#usa#brazil

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

World War I: Germany signed an armistice agreement with the Allies in a railroad car in the forest of Compiègne on November 11, 1918.

#Omri Amrany#World War 1 Monument#Community Veterans Memorial#travel#Munster#Indiana#Allan Harding MacKay#Toronto#Canada#Ontario#USA#11 November 1918#anniversary#history#WWII#World War Two#vacation#Ontario Veterans Memorial#Trois-Rivières#Québec#sculpture#cityscape#Monument to the Brave by Cœur-de-Lion McCarthy#Vimy Ridge Cross#Québec Citadelle#Halifax Citadel National Historic Site of Canada#Ottawa#National War Memorial by Vernon March

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anonymous asked: Do the French commemorate Remembrance Day and wear the red poppy to commemorate the dead?

Yes, of course they do. It’s called Armistice Day - and it’s 11 November. As time went on, the day came to mark the victims of all wars and several countries changed the name – in the UK it is now Remembrance Day and in the US it is Veterans Day – but France has stuck with Armistice Day.

The Great War officially ended with the signing of the Treaty of Versailles on June 28, 1919. But 11 November is chosen because it commemorates the signing of the armistice between Germany and the Allies that led to the ceasefire and finally put an end to World War I in 1918 - which took place at the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month in 1918.

It’s a national holiday and also a time to remember the war dead. There are memorial services all over France. All municipalities, regardless of their size, have a commemorative ceremony. A wreath of blue-white-red flowers is placed on each War Memorial, which is located either on the town’s square or by the church.

The President of the Republic presides over the Parisian comemoration and lays a wreath on the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier under the Arc de Triomphe at 11am. Two consecutive minutes of silence are observed at 11am local time. The first minute is dedicated to the nearly 20 millions people who lost their life during World War One. The second pays tribute to the living left behind, the mourning mothers, wives, brides to be and sisters. It’s quite a solemn and moving ocassion.

The red poppy, synonymous with Remembrance Day in the UK, is not used however. Instead the symbol of remembrance in France is the bleuet, or cornflower.

Although it is reported that France showed solidarity with the USA in 1920 (and again, with other World War One Allies, in 1921) by wearing the Remembrance Poppy, it is the cornflower (le bleuet) which was eventually adopted as the country’s memorial flower.

The young French army recruits, who arrived at the Front from 1915 onwards, were called “les bleuets” – because of the new blue version of jackets. Thus, there was a personal French connection with the dainty blue flower - that also grew profusely on the battlefields, with the poppy. It would make sense for the French to choose the bleuet because cornflowers have traditionally symbolised “pure and delicate” sentiments.

As with the Madame Guérin’s Poppy Day idea, as an emblem of remembrance and to help victims of war, French women were behind the idea of the cornflower / le bleuet as the memorial emblem of France. They were Suzanne Lenhardt and Charlotte Malleterre. It’s more than likely that Madame Guérin knew about le Bleuet, given it was begun in Paris in 1915, when she came up with her own red poppy idea.

Suzanne Lenhardt was a nurse and her husband had been killed on the Massiges battlefield, in the Marne. Charlotte Malleterre was daughter of General Niox - who was Commander-in-Chief of the hospital ‘Hôtel des Invalides’.

The two women arranged for the maimed French veterans (“les gueules cassées”) of the ‘Hôtel des Invalides’ to make the bleuets as an aid to their rehabilitation and as a means of earning money of their own. Such an occupation was the only thing many could have coped with. As Madame Guérin, and her one-time French co-lecturer Robert Arbour, used to state whilst fundraising for these men – such men did not receive a pension when they were medically discharged.

The soldiers would craft the petals from fabric and stamens from newspapers. In the beginning, les bleuets were only sold locally, in Paris, and not on a national scale. But that has changed in recent years as it is available nationally now.

The bleuet campaign is run on behalf of the Office National des Anciens Combattants et Victimes de Guerre and supports families of servicepeople or police officers who died or were injured in service, as well as victims of terrorism. Profits from bleuet sales go to veterans’ charities. However the flower is less ubiquitous in France than the poppy is in Britain. Why that is, I don’t know. But you do see more people wearing it as the years have increasingly passed.

Alongside my poppy, I wear it as a mark of respect for my French partner’s family, but also for the country I currently make my home. It’s also a way to honour the war dead of France who sacrificed their lives for their homeland and our freedom.

Thanks for your question.

#ask#question#remembrance day#armistice day#11 november#poppy#bleuet#cornflower#war#first world war#france#memorial#commemoration#europe

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

"IF YOU WERE AN ordinary person living in Canada in the winter of 1918– 19, you might well have thought that the world was coming down around your ears.

World War I had ended at 11 a.m. on Monday, November 11, 1918. Word of the armistice reached Canada in the early hours of the morning. As people heard of it, they spilled from their houses into the streets, some of them still in their pyjamas and nightgowns, congregating on street corners to toast the peace. After more than four years of war, there was a passion to celebrate. In Toronto, a pre-dawn procession of munitions workers, mainly women, paraded down Yonge Street, beating on pots and pans and blowing whistles. Towns and cities erupted in a noisy jubilee: sirens began wailing, factory whistles blew, church bells rang. Bonfires crackled on street corners and fireworks exploded. In the prairies, haystacks burned brightly in the fields. When daybreak came, work was forgotten as downtown thoroughfares filled with celebrants. Effigies of the German Kaiser were strung up and set ablaze. Civic officials hastily organized victory parades where Canadians expressed their relief that the war was finally over. Churches held special services of thanksgiving. The acting prime minister, William Thomas White (Prime Minister Robert Borden was already in England preparing for peace talks), dashed off a telegram to Arthur Currie, commander of the Canadian forces, commending their “courage, endurance, heroism and fortitude.”

But the euphoria did not last for long. Once the hangover of celebration wore off, Canadians woke up to the realization that there was no peace. Instead, everywhere in the world there seemed to be violence and turmoil: revolution in Germany and Hungary; civil war in Russia; uprisings in China and India; war in Afghanistan; general strikes in major cities across the United States. It was the Bolsheviks, people said; they seemed to be everywhere, overturning governments, seizing private property, and imposing their radical ideas. For some, these foreign “Reds” represented hope for a more just society; for others, they were a dangerous evil let loose to prey upon mankind.

If unrest was the rule around the world, why not in Canada? The war had left many Canadians disappointed and anxious about the future. The cost of living had been rising at three times the pace of wages. Working people found themselves poorer off than before the conflict began. As demobilized veterans returned home looking for jobs, a looming unemployment crisis threatened the economy. Returning soldiers were angry to find recent immigrants and people who had not put their lives at risk during the war occupying positions that they thought should belong to themselves.Conscription had opened an ugly division between French and English Canada. Under Borden’s Conservative government, political life seemed to have achieved unprecedented levels of corruption. The government and the press were engaged in a full-blown panic about the threat to the Canadian way of life posed by foreign agitators and labour radicals. Professor O.D. Skelton wrote in the Queen’s Quarterly:

The strain of war has produced a reckless and desperate temper. The world cannot be torn up by the roots for five years without destroying much of the old stability and acquiescence in the established order.

Canadians wondered what the war had been all about if the result was so much uncertainty, so much turmoil. They were proud of their country’s contribution to the conflict, but unsure about how to make it count for something. Surely more than 60,000 young Canadians had not given their lives just to preserve the status quo. The sacrifice seemed to demand a better way of doing things. A thirst for significant change cut across all stratas of society, from factory workers to farmers, from church ministers to returned soldiers to politicians. The federal cabinet minister Newton Rowell summed it up:

We cannot go back to old conditions, if we would, and we ought not to, even if we could.

But there was little agreement about what a new, improved Canada might look like. At a conference on reconstruction organized by the federal government in Ottawa, business leaders revealed their suspicion of even the most basic reforms, preferring instead a return to “normalcy,” by which they meant the way things had always been. That was the conservative, go-slow approach to post-war policy making: change if necessary but not necessarily change. What was the point of winning the war against Kaiserism, they wondered, if it led to Red revolution at home? More assertive voices for change emanated from the Protestant churches, which before the war had organized the Social Service Council to advocate for progressive social reform. The Council threw its support behind “industrial democracy” and a wide-ranging set of social welfare policies, including mothers’ allowances, unemployment insurance, and old-age pensions. The Methodists went farther still, calling for “nothing less than a complete social reconstruction” of postwar Canada.

Yet even this clarion call did not go far enough for political activists in the labour movement and the various socialist parties. They adopted the rhetoric of world revolution. Nothing would satisfy these radicals short of an overhaul of the structure of economic ownership in the country. “Are we in favour of a bloody revolution?” asked Calgary labour organizer Jean MacWilliams, appearing before a government commission in the spring of 1919. “Why any kind of revolution would be better than conditions as they are now.” In other words, what was the point of winning the war in Europe if it did not lead to revolution at home?"

- Daniel Francis, Seeing Reds: the Red Scare of 1918-1919, Canada’s First War on Terror. Arsenal Pulp Press, 2011. p. 9-12.

#world war 1 canada#world war 1#end of world war 1#fear of a red planet#postwar reconstruction#labour revolt#bolsheviks#russian revolution#communism#anti-communism#research quote#reading 2024#canadian history

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Map of Europe on 11 November 1918 (Armistice day)

78 notes

·

View notes

Photo

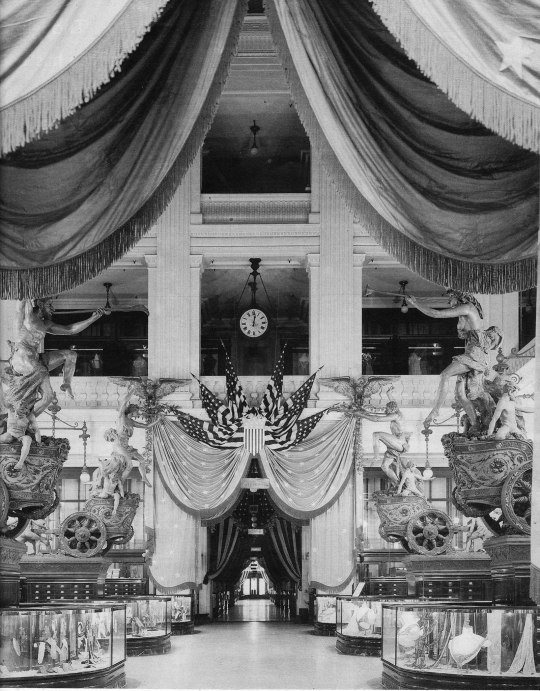

November 11, 1918 - Armistice Day decorations at the Marshall Fields Department Store. From Department Stores Remembered, FB.

139 notes

·

View notes

Text

11 November 2018 | Prince William, Duke of Cambridge and Catherine, Duchess of Cambridge attend a service marking the centenary of WW1 armistice at Westminster Abbey on November 11, 2018 in London, England. The armistice ending the First World War between the Allies and Germany was signed at Compiègne, France on eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month - 11am on the 11th November 1918. This day is commemorated as Remembrance Day with special attention being paid for this year's centenary. (c) Leon Neal/Getty Images

#Catherine#Duchess of Cambridge#Princess of Wales#Prince William#Duke of Cambridge#Prince of Wales#Britain#2018#Leon Neal#Getty Images

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

A 17-year-old Canadian soldier lies in a casualty clearing station. He was wounded only 15 minutes before the Armistice on 11 November 1918. Although the legal age requirement for Canadian soldiers was between 18 and 45, thousands of male adolescents served overseas as illegal underage soldiers.

#historical photos#the first world war#world war one#wwi#1917#world war 1#the great war#history#ww1#canadian history

49 notes

·

View notes