#National Socialism

Text

#second pic was obtained during my field research in a nazi channel posted unironically ofc#pagans#larpers#nazis#national socialism#fascism#tw disney mention#tw larpers#tw cringe#tw embarrassing#funny#found#e anthropology

92 notes

·

View notes

Text

The murder of people with physical, mental, and psychological disabilities was also directly linked to economic concerns — it was intended to rid the economy of people who were considered a burden. The Nazi language was quite economic and financially minded in this respect. For example, a typical propaganda poster read: “60,000 Reichsmarks throughout his life: that is the cost of this hereditary sick person for the Volksgemeinschaft [the Nazi word for national community]. Volksgenosse [national comrade], that is also your money.”

Even the Shoah is related to economic considerations. For in Nazi ideology, Jews were seen as the ultimate obstacle. Obstacle to what? To capitalism, not least. They were considered the backbone of Marxism. The Nazis construed Marxism as an essentially Jewish conspiracy against the capitalist economy — and thus against the natural order. Of course, the Shoah was the result of many factors and the culmination of various Nazi obsessions, phobias, and hatreds. But among all these, one shouldn’t lose sight of this socioeconomic factor.

The Nazis Weren’t Socialists — They Were Hypercapitalists

130 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alex Jones is getting swarmed on Twitter literally, actually because he said "fuck Hitler"

The man is down there in the replies trying to these retards basic historical facts and none of them can even process them. It's like Kanye all over again-Alex Jones is desperately trying to convince people that the Nazis were bad and the Holocaust was real(he's said he had a relative who liberated a camp, and if that's true I can definitely see why he'd be very invested in that not being lied about), and nobody is willing to listen. Not because he's the boy who cried wolf, but because he stopped crying it and that was all they ever wanted to hear from him.

#alex jones#twitter#x#infowars#conspiracy theory#nazis#nazism#national socialism#pro-pals take note#this is where you'll be this time next year#israel#palestine#gaza#gaza strip#gaza war#the last five tags are the reason there are suddenly so many Holocaust deniers and Hitler-defenders out in the open these days

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“オークション・ハウス Auction House Vol.3” Kazuo Koike, Seisaku Kanou 1991

#comics#comic books#manga#auction house#kazuo koike#seisaku kanou#national socialism#fascism#uniform#nazi

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

"This is a sobering study of how quickly and completely German universities and the humanities were corrupted by Nazi ideology and policies during the National Socialist era. Led by some of the most prominent scholars in their fields, entire scholarly disciplines conformed to Nazi rule, leading to the broader perversion of humanistic values, standards and ethics throughout Germany. Thoughtful and profound, the essays in this volume explore this history as a warning for our own times."

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

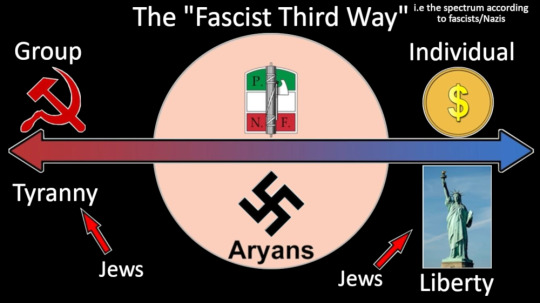

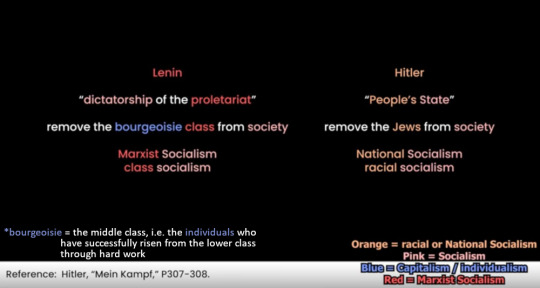

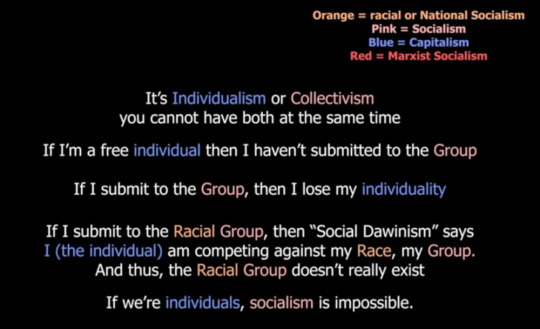

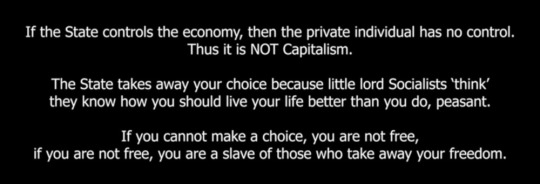

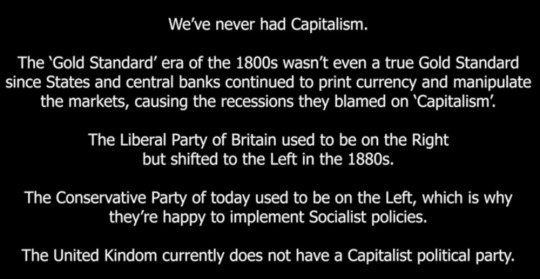

Since the current political environment is so mixed up by bad actors that the majority of people don't know what they are actually advocating for, here is a compact lesson so you know what you are voting for. These slides are from TIKhistory (mostly) who has done his own research after being disenfranchised by the left.

This is not to say that, to use the US as an example, the Republican party is 'good' or even on the right. This should show that even the Republican party is not even on the right anymore and both major parties in the US are on the left; just that the Democratic party is more left than the Republican. Both are bad if you value your individuality, personal freedom, and ability to own your own stuff without corporations breathing down your back.

#politics#socialism#capitalism#fascisim#left vs right#political parties who say they are on the 'right' aren't always actually on the right#the far right would be anarcho-capitalism or no state/government and free market driven purely by supply and demand of individuals#political spectrum#marxism#communism#leftism#right wing#left wing#republicans#democrats#national socialism#long post

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I just read this thread on reddit in a state of jaw-dropped incredulity, over just how many people tried to argue the WWII nazis were socialist.

It's one thing to know that people will make that argument, but to see so many idiots or propagandists...

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Germany, ca. 1940

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Classical liberalism “had a good war.” In 1944, two seminal books in this tradition of thought were published. The first of these was F.A. Hayek’s The Road to Serfdom, the other Omnipotent Government by Ludwig von Mises. They were complemented the following year by Karl Popper’s Open Society and Its Enemies.

Hayek’s book soon became a classic, and it is still considered a force to be reckoned with. Mises’s book has been less fortunate. Yet it is an important contribution, for at least two reasons. On the one hand, Mises offers his explanation of what made German politics degenerate to the point of trusting her fate into Hitler’s hands.

On the other hand, Mises offers a complex understanding of the consequences of what he calls “etatism” in the international sphere. Mises uses “etatism” instead of statism because that word, “derived from the French état… clearly expresses the fact that etatism did not originate in the Anglo Saxon countries, and has only lately got hold of the Anglo-Saxon mind.”

(…)

The world parted from liberalism in two key ways. In a liberal world, “frontiers are drawn on the maps but they do not hinder the migrations of men and shipping of commodities. Natives do not enjoy rights that are denied to aliens.” One may think of perhaps the most extraordinary passage in Pericles’s funeral oration: Athens, he claimed, is open “to the world, and never by alien acts to exclude foreigners from any opportunity of learning or observing, although the eyes of an enemy may occasionally profit by our liberality.” That sense of openness as an essential mark of a liberal polity is central to liberalism in Mises’s view (though of course he had a more inclusive understanding of political right). For him, embracing liberalism would be the only effective guarantee of world peace: any other solution than embracing free trade and open borders is bound to develop conflict between states.

(…)

If Omnipotent Government seems bitter, it does so because Mises thought “etatism” made conflict widespread and potentially unavoidable. “A democratic commonwealth of free nations is incompatible with any discrimination against large groups,” but modern politics thrive on such discrimination—which are apparent in trade and migration barriers. Etatism”must lead to conflict, war, and totalitarian oppression of large populations:” for Mises, it breeds conflict and thrives on conflict. “In our age of international division of labor, totalitarianism within several scores of sovereign national governments is self-contradictory. Economic considerations are pushing every totalitarian government toward world domination.”

Etatism breeds monism and intolerance. “The right and true state, under etatism, is the state in which I or my friends, speaking my language and sharing my opinions, are supreme. All other states are spurious. One cannot deny that they too exist in this imperfect world. But they are enemies of my state, of the only righteous state, even if this state does not yet exist outside of my dreams and wishes.”

(…)

While he was often dismissed as a laissez-faire ideologue, Mises’s explanation is historical and nuanced. He tracks the decline of the fortune of German liberalism and the rise of nationalism, trying to refuse easy and mistaken explanations. While he was deeply pessimistic about the spirit of the age (“It seems that the age of reason and common sense is gone forever,” he wrote to Hayek in 1941), his work attempts to be a logical, cold analysis of what happened.

(…)

Mises’s work is idea-centric: he attaches great importance to the fashions of the intellectual world. Politics is a matter of interests, but the dominant ideas in society make those interests intelligible to the very people who hold them. Ideas anticipate and draw the space of the politically possible. The prevailing ideas, in Germany, brought people to consider their nation as a “closed” economic system and to believe that its success depended upon other governments’ failures. “Etatism” becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy: “the most advanced countries of Europe have poor domestic resources. They are comparatively overpopulated.” As a trend “towards autarky, migration barriers, and expropriation of foreign investments” consolidates, they are bound to experience a severe fall in standards of living.

If “the old liberals were right in asserting that no citizen of a liberal and democratic nation profits from a victorious war,” when you introduce “migration and trade barriers” everything changes. The economy becomes a realm of conflict, not of co-operation. “Every wage earner and every peasant is hurt by the policy of a foreign government, barring his access to countries in which natural conditions of production are more favorable than in his native country. Every toiler is hurt by a foreign country’s import duties penalizing the sale of the products of his work.”

Had Germany adopted free trade and liberalism, these ideas would have gained center stage in continental Europe. But not only it did not happen: the fact that the entire world of politics was openly anti-liberal determined that possible opportunities to move in a liberal direction were never grasped.

A turning point was the end of WWI. “The main argument brought forward in favor of the Hohenzollern militarism was its alleged efficiency.” For Mises the First World War “destroyed the old prestige of the royal family, of the Junkers, the officers, and the civil servants.” By late 1918 “the great majority of the nation was sincerely prepared to back a democratic government.” But the Marxist elements of the Social Democratic Party withdrew their support for democracy, hoping to hasten towards the Revolution. Yet that created the impression that “as the conservatives had always asserted, the advocates of democracy wished to establish the rule of the mob.” Thus “the idea of democracy itself became hopelessly suspect.” For Mises, “the nationalists were quick to comprehend this change in mentality.” Very quickly German politics degenerated into a sort of war between “extreme” groups, Marxist and nationalist: “there was no third group ready to support capitalism and its political corollary, democracy.” Those who thought they were opposing nationalism were “fanatical supporters of statism and hyper-protectionism. Bt they were too narrow minded to see that these policies presented Germany with the tremendous problem of autarky.”

Such an ideological climate, together with the Marxists flirting, made for “a spirit of brutality” that gave “political parties a military character.” “If Hitler had not succeeded in winning the race for dictatorship, somebody else would have won it.”

(…)

The Nazis conquered Germany because they never encountered any adequate intellectual resistance. Mises insists that this happened because “the fundamental tenets of the Nazi ideology do not differ form the generally accepted social and economic ideologies.”

(…)

For Mises, what consolidated Nazism was the fact that statism was the hegemonic ideology in the Western world too. Instead of being inclined towards international cooperation and trade, other countries faced Germans in the way the Nazi expected—and that allowed them to grow consensus.

(…)

Mises’s liberalism in this book is, as always, adamant. “It is a delusion to believe that planning and free enterprise can be reconciled. No compromise is possible between the two methods. Where the various enterprises are free to decide what to produce and how, there is capitalism. Where, on the other hand, the government authorities do the directing, there is socialist planning.” But it will be wrong to take this for an uncritical endorsement of “real world capitalism.” He sees the emergence of a businessman’s syndicalism (crony capitalism, we would call it) as “something like a replica of the medieval guild system. It would not bring socialism, but all-round monopoly with all its detrimental consequences. It would impair supply and put serious obstacles in the way of technical improvements. It would not preserve free enterprise but give a privileged position to those who now own and operate plants, protecting them against the competition of efficient newcomers.”

Omnipotent Government may be seen by some as an overly economistic attempt to make sense of totalitarianism. Indeed, there was more to Nazis than their system of price controls. But it is precisely for this reason that it is such a fascinating read. Brutality, hatred and the pride some political groups take in aggression are traced back to a flawed understanding of the world, propelled by their rejection of liberalism. Omnipotent Government is a testimonial to the power of the economic way of thinking and to Ludwig von Mises’s analytical power.”

“Back on Feb. 16, the New Hampshire Bar Association held its annual mid-year meeting. This year the program was a little different. Instead of the usual continuing legal education event, the bar brought in two historians, Anne O’Rourke and Willliam Meinecke Jr., from the United States Holocaust Museum to look at how German lawyers and judges responded to the destruction of democracy and the establishment of the Nazi state.

Their presentation showed that the worst horrors of the Nazi regime did not arrive full-blown. Rather, the road to fascism was taken in gradual incremental steps, each one preparing the way for the next.

While German lawyers and judges might have opposed Hitler’s authority and the legitimacy of the Nazi regime, they failed to do so. Not only did they fail, they collaborated and interpreted the law in ways that broadly facilitated the Nazis’ ability to carry out their agenda.

(…)

O’Rourke and Meinecke pointed to a number of decrees by the Nazis that they used to consolidate their power and advance their program. After the February 1933 fire in the Reichstag, the German parliament, the Nazis suspended critical provisions of the German constitution, including right to assembly, freedom of speech and freedom of the press.

They also removed all restrictions on police investigations. They rounded up political opponents, particularly communists, socialists and social democrats, holding them in preventive detention and sometimes disappearing them altogether. Relying on the Reichstag Fire Decree, the Nazis held people without specific charges. Defendants had no right to appeal, no access to a lawyer or right to judicial review.

The German Supreme Court did not balk at the new power arrangement. Sadly, the court failed to challenge or protest the loss of its judicial authority.

Less than one month after the Reichstag Fire Decree, the Nazis enacted an Enabling Act that allowed them to promulgate and establish laws that violated the Weimar Constitution. Under the Enabling Act, they did not need the approval of then-President von Hindenberg or the parliament. The passage of law had previously required a two-thirds majority vote in parliament.

The Nazis prevented their parliamentary opponents from taking their seats, detaining them in camps. They stationed their thugs in the parliamentary chamber to intimidate remaining representatives.

The German Supreme Court did nothing to challenge the Enabling Act. The court saw itself as a loyal state servant, owing allegiance to Hitler. Law became a means to serve the Aryan race. What was defined as good for the race became good law.

In July 1933, the Nazis enacted another new law against the founding of new political parties. With this law, they outlawed all other political entities and made themselves the only allowed party in Germany.

When President von Hindenberg died in August 1934, Hitler assumed power as Reich chancellor and fuhrer. The oath of loyalty for all state officials was changed. Rather than pledging loyalty to the German constitution, a new oath required loyalty to the fuhrer.

(…)

By April 1933, the state ministries of justice suspended from duty all Jewish judges, public prosecutors and district attorneys. Also all professors of law who were Jews and those few who were not conservatives were driven out of universities and dismissed.

About this time period, the Holocaust historian Raul Hilberg wrote: “A lawyer necessarily had to face at every turn the critical question of harmonizing peremptory measures against Jews with law. In fact this alignment was his principal task in the anti-Jewish work. Yet in the end lawyers, no less than physicians, mastered those mental somersaults.”

It is impossible to know what degree of ambivalence or conflict German lawyers and judges had with the Nazification of the law. Hilberg wrote that the Nazis were obsessed with a need for legal justification. Even with the death of due process and any semblance of individual rights, the Nazis craved the appearance of legality.

Years before the Holocaust, the German judiciary had already rationalized the absolute debasement of law at the service of the Nazis. Considering the early years, what came later cannot be too surprising. There was never any outrage about the systematic removal of Jewish lawyers and judges from the German legal world.

So what lessons can we learn from the German experience? Why did the lawyers and judges turn out to be so weak, pliable and accommodating?

First, I would cite the failure of critical thinking by both lawyers and judges. They offered themselves up to the Nazis to do their bidding. The legal profession proved to be either too conformist or careerist to take chances and rock the boat. Lawyers and judges played it safe to try to get ahead.

By going along, they gave the Nazis a big gift, what the historian Timothy Snyder has called “anticipatory obedience.” If lawyers and judges had said “no” that would have caused significant problems. The Nazis desperately wanted at least the appearance of lawyer/judge buy-in to give themselves legitimacy.

Sadly, as Snyder pointed out in his book On Tyranny, most of the power of authoritarianism was freely given. The Nazis’ rise to power relied on zealous support from German conservatives and nationalists in the courts.

There was a massive failure of professional ethics. Somehow doing the right thing was replaced by subordination to a demagogue. We should remember that lawyers were vastly over-represented among the commanders of the Einsatzgruppen. The Einsatzgruppen were the death squads of Nazi Germany who were responsible for mass murder of Jews, Gypsies, Polish elites, communists and the handicapped.

The experience of German lawyers and judges shows the need for a genuinely independent judiciary, regardless of what political party holds power. Without genuine independence, justice as an ideal disappears. What is left is glorification of power.

In all that has been written about the Nazis, I find it surprising how little attention has been paid to the collaborationist role of lawyers and judges. In an allegedly rule-of-law state, the Nazis needed lawyers and judges. For Americans today, the German experience provides a sobering example of how a nation’s legal and judicial systems can be made to aid and abet a rogue regime’s gradual descent into barbarism.”

#mises#ludwig von mises#Omnipotent Government#hayek#Friedrich Hayek#road to serfdom#jonathan p baird#naziism#national socialism#fascism#totalitarianism#liberalism#statism#etatism#law#lawyers#supreme court#weimar#germany

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

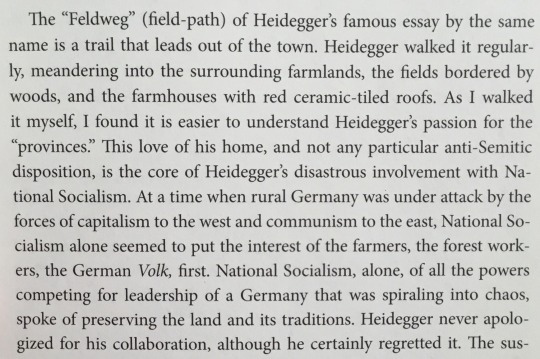

From the preface to S.J. McGrath, The Early Heidegger & Medieval Philosophy: Phenomenology for the Godforsaken.

7 notes

·

View notes

Link

NILS SCHNIEDERJANN Then why did they use the word “socialism” at all?

ISHAY LANDA We have to understand the context in which they applied the term. In our own days, right-wing politicians no longer use the term. Why? Because socialism is no longer so popular. But back then, anti-communists faced the challenge of gaining access to socialist strongholds and convincing as many working-class voters as possible. So, they had to present their policies as agreeing with the interests of the working class. The trick was to benefit from the popularity of socialism, which was widely seen as the force of the future, but at the same time to distance themselves as much as possible from its substance.

NILS SCHNIEDERJANN If the Nazis called themselves socialists only for strategic reasons, what did their economic policies actually look like?

ISHAY LANDA They were strongly capitalist. The Nazis placed great emphasis on private property and free competition. It’s true that they intervened in the free market, but it was also a time of a systemic failure of capitalism on a global scale. Almost all states intervened in the market at the time, and they did so to save the capitalist system from itself. This has nothing to do with socialist sentiment: it was pro-capitalist. In a way, there’s a parallel there with the way big banks were bailed out by governments after the 2008 financial crisis broke out. That, of course, did not reflect socialist intentions in any way, either. It was merely an attempt to stabilize the system a little bit.

251 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

“In such circumstances the tension between Ernst Thälmann’s footdragging on the issue of nationalism and Moscow’s priorities came to a head over the tactics to adopt when the Nazis forced a plebiscite to oust the social democratic government of Prussia. The vote was due on 9 August 1931. Under Thälmann’s direction, on 15 July the Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands leadership decided as a matter of principle to abstain. Any association with the Nazis was ruled out. Even the more radical Heinz Neumann appeared to go along with the decision. “Some” of the comrades in Moscow at Comintern’s secretariat also thought this the correct line to take: probably the moderate Kuusinen and doubtless the sinuous but not unintelligent Manuilsky. But as soon as word spread, others—probably the leftists Pyatnitsky and Vil’gel’m Knorin, egged on by Neumann—appealed over the heads of the German leadership to Stalin.

...

The Prussian plebiscite proved a dangerous fiasco that destroyed any chance of a united front against fascism in Germany and yet failed to make the KPD a credible voice for nationalism. A great victory was declared by Comintern and the KPD—Neumann, indeed, claimed that the central government and the Prussian administration were now “peeing in their pants”—even though insufficient numbers voted to oust the SPD from power in Prussia. All this did was to alienate social democrats even further, and not just them. The shortfall was attributable not least to the fact that core Communist districts failed to participate. This was, indeed, a serious matter. Most supporters of the KPD were simply unwilling to throw out the socialists. The doctrine of social fascism was thus effectively being ignored among the rank and file of the party. Stalin’s opportunism had tipped the largest Communist party in Europe, and therefore Moscow’s best asset, into prolonged crisis.

...

Before long Manuilsky could be heard acknowledging that fascism had not been blocked in Germany as “some comrades” had asserted, and that “in fact in no country had the growth of fascism been brought to a halt”. Worse still, the party in Germany appeared to be all over the place. On 17 November 1931 the KPD daily Die Rote Fahne spoke of Social Democracy as the main menace. Five days later it named the Centre Party. Comintern’s German policy was in tatters. But the underlying reason for the chaos was unmentionable, even within the walls of Comintern: Soviet state interests, as conceived by Stalin, had to be served. At all costs the Centre Party and the Social Democratic Party of Germany had to be removed from the levers of power or the convergence between debt-ridden Germany and the Entente would continue, leaving Moscow isolated and therefore vulnerable to the emergence of a hostile coalition.

The KPD was lambasted for not doing enough to combat the Nazis, who were seen by the party as fundamentally “anti-capitalist” and passively making gains on the back of dissatisfaction with government. They were seen as doing a better job of exploiting discontent, the implication being that the Communists should learn from them. Indeed, Thälmann made a Freudian slip in rating Hugenberg’s nationalist party against “the not so right-wing [sic] party of the Nazis”. Inevitably the KPD was bewildered and demoralised by signals from Moscow. As late in the day as 10 April 1932 Stalin was still insisting that “the main blow” should be aimed at Social Democracy. And this was after the presidential elections of 12 March, when Hitler obtained 30.1% of the vote against Thälmann’s tiny 13.2% and Hindenburg’s 49.6%.

The disconcerting spectacle all too visible to Comintern was that the Nazis were making alarming headway in recruiting from workers in enterprises where the Communists had been predominant. It soon became obvious where former KPD activists were going. KPD party membership rose as never before, but these were new members. Moreover, the numbers voting Communist in key working-class districts of Berlin such as Wedding and Friedrichshain were lower than in the May 1928 elections. All of this was cause for “serious alarm”. In this respect Thälmann’s speech to Comintern’s executive committee on 19 May was scarcely reassuring.

Thälmann was inevitably depressed by the outcome of the elections. It was a defeat generally recognised as such within Comintern, despite Pyatnitsky’s attempts to lighten the blow with reassuring denials. Yet Thälmann clearly understood that his hands were largely tied by Comintern’s commitment to the doctrine of social fascism. The KPD could not block the election of a Nazi to the Prussian Landtag “because it is not permissible to enter into horsetrading with Social Democracy and even less with the Centre as the governing party”. Moreover, his analysis of the Nazi Party and its growing popularity was bleak but spot-on:

The question is: why has the National Socialist Party such a colossal following? It is not only a question of the party being so active. It is not only a question of it conducting massive agitation and propaganda; it is not only a question of the millions provided by the bourgeoisie for these elections and other elections; but it also has to do with the existence of chauvinist and nationalist sentiment in Germany.… The Hitler movement positions itself as the movement that fights against the system and enables it to mobilise expressions of discontent and anti-capitalist opinion in Germany (general opposition to the Versailles system is also very strong) into their ranks.

...

Even diehards at Comintern headquarters momentarily began to suspect that they might be on the road to catastrophe when a new coalition government emerged on 1 June 1932 under the leadership of Franz von Papen for the Centre Party. With defeat staring him in the face, Knorin, the ultra-leftist heading Comintern’s Central European secretariat, panicked and raised the alarm:

Our party must now make every effort to reorganise itself in expectation of being outlawed. History has never known an instance of an 800,000- member party being forced underground. But we are now faced with … such a possibility.

Knorin now openly admitted that

Germany has a decisive significance for Comintern. Should fascism succeed in wiping out the resistance of the working class, should fascism succeed in forcing our party underground for a long time … then this would mean a colossal growth of the reactionary camp, it would mean fascism across the face of Europe.

Indeed.

...

On 4 April 1932 Stalin had told Thälmann’s nemesis, Neumann, that he was preoccupied with military matters and that left no time for Comintern. At this stage of the Depression other governments were increasingly sensitive to Comintern activity because of its international reach, even though the organisation was at its most sectarian and was therefore losing rather than gaining members. In May the Swiss minister in Rome had an audience with Mussolini, who in a bid to dominate the table played the anti-Communist card:

He told me that the four European great powers, France, Germany, England, and Italy, have to restore order in Europe; otherwise we are heading for one of the most serious social crises, the bolshevisation of Europe. Bolshevik propaganda is pervasive everywhere in all guises. Our bourgeois class is itself completely penetrated. Throughout Europe, not excluding Italy, the working class is convinced that the Bolshevik régime has succeeded.

It is by no means certain that knowing this would have reassured the Soviet leadership; rather the reverse is possible. The common fear of Bolshevism without doubt cemented relations between the antagonistic capitalist powers. Secret intelligence indicated that the German government was seeking common ground with the French at Soviet expense. Indeed, at the Lausanne conference of the major European powers on 29 June Papen, who counted on the Americans to ease reparations payments, proposed military conversations with the French for common action against the Soviet Union—a proposal that was, no doubt to Stalin’s relief, dismissed out of hand. Anxious not to make matters worse, given Papen’s fierce anti-Communism, Stalin vented his fury at “disastrous” attacks launched on the Papen government by the Soviet press. The consequences of his immediate priorities soon became apparent.

Comintern’s secretariat was largely on its own. It was frozen in place by Stalin’s previous decisions without any flexibility permitted to improvise policy for the KPD. In addition, Stalin’s habit of confiding in Neumann, who had nominally been in the dock since the spring of 1930 over his ultra-leftism, seriously undermined the authority both of Comintern’s secretariat and of Thälmann. Only shortly after he had made the case for anticipating a fascist coup Knorin, along with Pyatnitsky, refused to go along with a proposal made by Thälmann, who wanted to stop the election of a Nazi as chairman of the Prussian parliament even by means of voting for a socialist or Centre Party candidate and had the agreement of the majority within Comintern’s secretariat.

In Moscow the heightened vigilance during that summer proved all too brief. It dropped precipitously when the Reichstag elections on 6 November 1932 fortuitously delivered a rise in votes for the KPD and a fall in support for the Nazi Party. This inevitably sent a welcome wave of euphoria through Comintern and the German Communist leadership, who were now tempted to believe that the crisis was finally past. It proved a fatally beguiling mirage. One clue to the staying power of unrealism was the obviously demoralising consequence of acknowledging how far policy hitherto had been misdirected.”

- Jonathan Haslam, The Spectre of War: International Communism and the Origins of World War II. Princeton & Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2021. pp. 121-127.

#kommunistische partei deutschlands#comintern#weimar republic#weimar germany#crisis of the weimar republic#international relations#communism#soviet union#ernst thalmann#franz von papen#lausanne conference#national socialism#social fascism#nsdap#german politics#stalinism#german history#academic quote

1 note

·

View note

Text

Keep talking about Palestine!

#free palestine#palestine#signal boost#gaza#from the river to the sea palestine will be free#social justice#palestine resources#colonialism#imperialism#jerusalem#the west bank#end the occupation#tel Aviv#human rights#united nations

69K notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Lefranc - Tome 26. Mission Antarctique” François Corteggiani, Christophe Alvès 2015

Cover illustration detail.

#cover art#comics#comic books#lefranc#jacques martin#christophe alves#francois corteggiani#science fiction#nazi#swastika#haunebu#nazi ufo#national socialism

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

A few weeks ago the UN reported that everyone in Gaza is facing a food crisis -and that 1 in every 4 people in Gaza are starving -a quarter of their population is hundreds of thousands of Palestinian people. EVERYONE is hungry -their medical systems have collapsed and there are imminent outbreaks of diseases. How HUMILIATING and dehumanizing it is to have to fight for basic necessities. Imagine seeing a humanitarian truck -something rare because as we know the IOF has been collectively punishing Palestinian people for months now and has been committing mass genocide under the guide of 'war.' Not letting through resources to prevent people from dying from starvation is beyond depraved. And the fact we will NEVER see this on western/European mass media is just... absolutely infuriating.

#feminist#feminism#social justice#free palestine#palestine#freepalastine🇵🇸#free gaza#settler violence#settler colonialism#current events#gaza strip#gaza#gazaunderattack#end the genocide#end the occupation#ceasefire now#ceasefire#human rights violations#human rights#united nations

23K notes

·

View notes