#UNESCO heritage sites

Photo

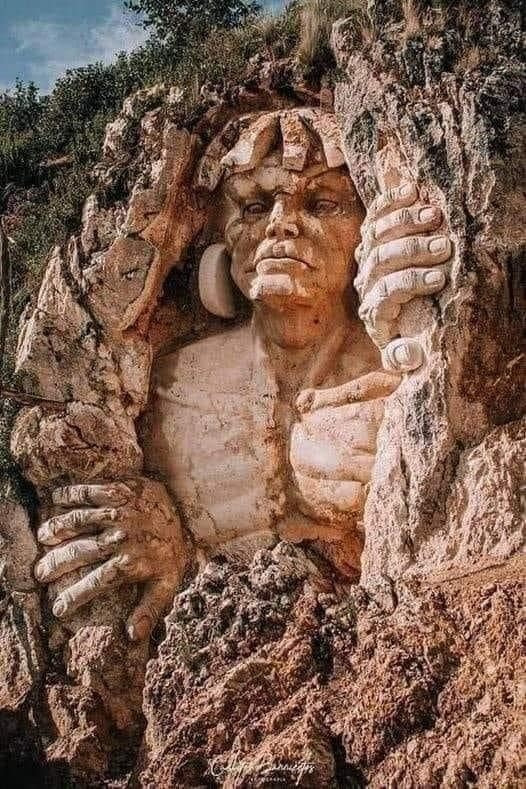

Apukunaq Tianan a Quechua (''The abode of the gods”) is a tourist attraction in Cusco, Peru that features 20-30 feet tall stone sculptures of Andean gods and sacred animals. Despite it’s ‘ancient’ appearance, these are modern sculptures created by sculptor Michael de Titan.

#Sculptures#Cusco#Peru#Peruvian attractions#travel#worth seeing#tourist attraction#Abode of Gods#wow#bucket list#artistic monuments#UNESCO heritage sites#Incan Gods

66 notes

·

View notes

Photo

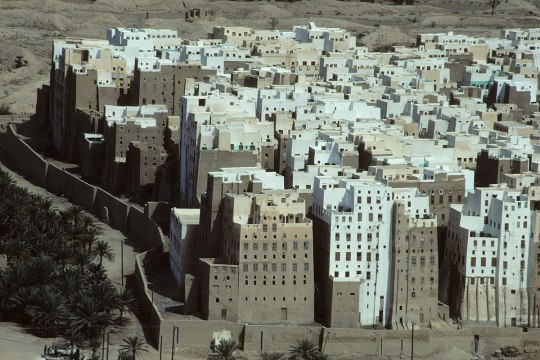

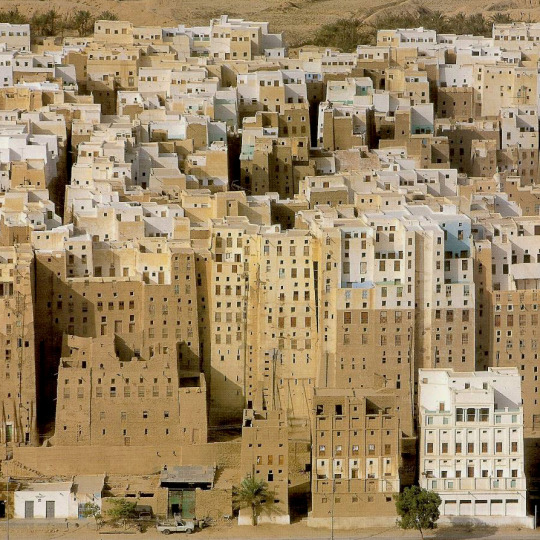

Shibam - This ~1,700-year-old walled city in Yemen is considered to be the oldest vertically constructed city in the world. Its trapezoidal buildings (most were built in the 16th century) are made of mud bricks and need constant maintenance due to rain and wind erosion.

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

Palacio Nacional de Mafra / Portugal (by Suzanne Tucker).

#portugal#visit portugal#mafra palace#architecture#baroque#royal palace#lusitania#unesco heritage site

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

#the hani rice terraces shu's design seems to be based on are absolutely gorgeous#highly recommend googling em#queen based off of a unesco heritage site fr#my art#arknights#arknights shu

494 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kölner Dom

Cologne, Germany

#photographers on tumblr#architecture#art#churches#windows#cologne#germany#cathedrals#kölner dom#cologne cathedral#köln#vertical#original photographers#original photography#gothic#unesco world heritage site#world heritage

242 notes

·

View notes

Text

there is a basilica in aquileia that has an ancient roman mosaic of a giant bowl of mushrooms on the floor and i have to admit, nothing would make me feel closer to god than that

#it's a unesco world heritage site now btw.#tagamemnon#queueusque tandem abutere catilina patientia nostra

503 notes

·

View notes

Text

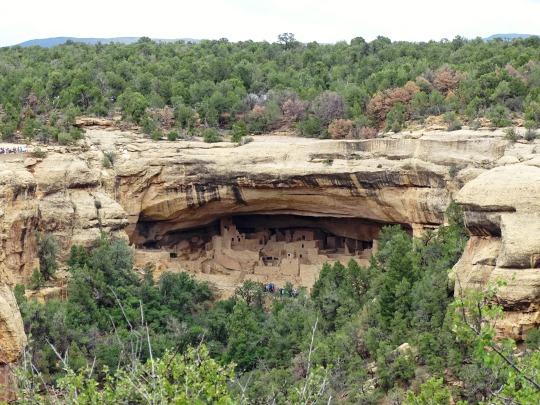

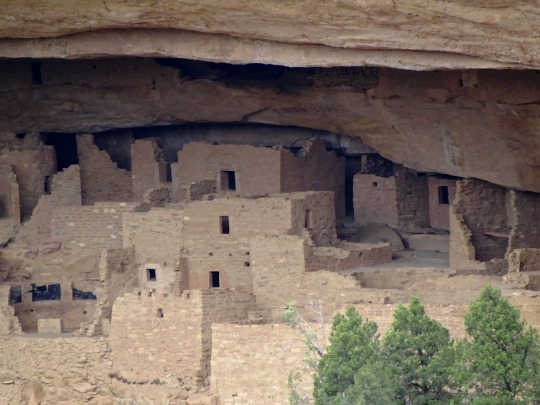

Cliff Palace, Mesa Verde National Park (No. 13)

Cliff Palace is the largest cliff dwelling in North America. The structure built by the Ancestral Puebloans is located in Mesa Verde National Park in their former homeland region. The cliff dwelling and park are in Montezuma County, in the southwestern corner of Colorado, in the Southwestern United States.

Tree-ring dating indicates that construction and refurbishing of Cliff Palace was continuous approximately from 1190 CE through 1260 CE, although the major portion of the building was done within a 20-year time span. The Ancestral Puebloans, also known as Anasazi, who constructed this cliff dwelling and the others like it at Mesa Verde were driven to these defensible positions by "increasing competition amidst changing climatic conditions". Cliff Palace was abandoned by 1300, though debate is ongoing as to the cause. Some contend that a series of megadroughts interrupting food production systems was the main cause.

Cliff Palace was rediscovered in 1888 by Richard Wetherill and Charlie Mason while they were looking for stray cattle.

Source: Wikipedia

#Cliff Palace#Mesa Verde National Park#cliff dwelling#Ancestral Puebloans#Colorado#UNESCO World Heritage Site#ancestral puebloan archaeological site#archaeology#Montezuma County#original photography#desert varnish#travel#vacation#tourist attraction#landmark#architecture#landscape#countryside#summer 2022#USA#Mountain West Region#tree#cliff

211 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sir Cecil Beaton in his bathroom decorated with autographed hands of guests, Ashcombe House, Wiltshire, UK, 1934

VS

Cueva de las manos, Santa Cruz, Argentina, 7300 BC

#cecil beaton#sir cecil beaton#ashcombe#ashcombe house#uk#dandy#hand#hands#Cueva de las manos#cave#unesco#world site heritage#shilouette#stencil

92 notes

·

View notes

Text

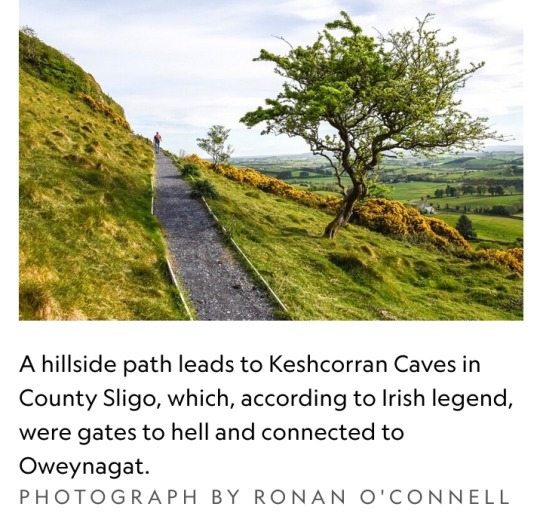

Story and photographs by Ronan O’Connell

September 26, 2023

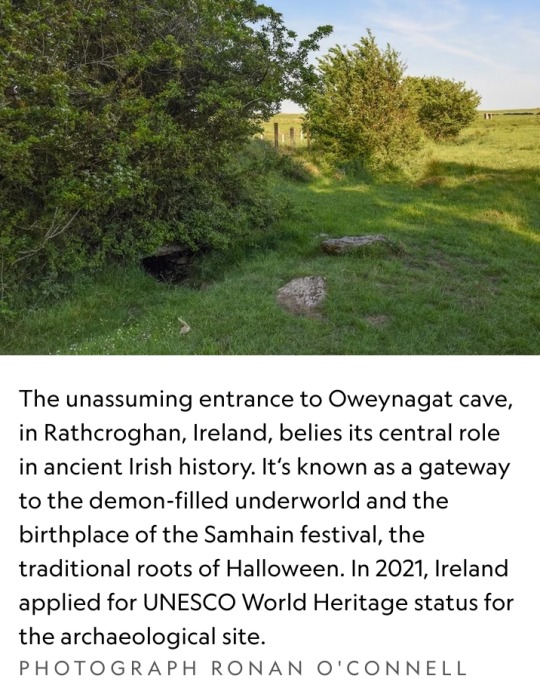

In the middle of a field in a lesser known part of Ireland is a large mound where sheep wander and graze freely.

Had they been in that same location centuries ago, these animals might have been stiff with terror, held aloft by chanting, costumed celebrants while being sacrificed to demonic spirits that were said to inhabit nearby Oweynagat cave.

This monumental mound lay at the heart of Rathcroghan, the hub of the ancient Irish kingdom of Connaught.

The former Iron Age center is now largely buried beneath the farmland of County Roscommon.

In 2021, Ireland applied for UNESCO World Heritage status for Rathcroghan (Rath-craw-hin). It remains on the organization's tentative list.

Rooted in lore

Spread across more than two square miles of rich agricultural land, Rathcroghan encompasses 240 archaeological sites, dating back 5,500 years.

They include burial mounds, ring forts (settlement sites), standing stones, linear earthworks, an Iron Age ritual sanctuary — and Oweynagat, the so-called gate to hell.

More than 2,000 years ago, when Ireland’s communities seem to have worshipped nature and the land itself, it was here at Rathcroghan that the Irish New Year festival of Samhain (SOW-in) was born, says archaeologist and Rathcroghan expert Daniel Curley.

In the 1800s, the Samhain tradition was brought by Irish immigrants to the United States, where it morphed into the sugar overload that is American Halloween.

Dorothy Ann Bray, a retired associate professor at McGill University and an expert in Irish folklore, explains that pre-Christian Irish divided each year into summer and winter.

Within that framework were four festivities.

Imbolc, on February 1, was a festival that coincided with lambing season.

Bealtaine, on May 1, marked the end of winter and involved customs like washing one’s face in dew, plucking the first blooming flowers, and dancing around a decorated tree.

August 1 heralded Lughnasadh, a harvest festival dedicated to the god Lugh and presided over by Irish kings.

Then on October 31 came Samhain, when one pastoral year ended and another began.

Rathcroghan was not a town, as Connaught had no proper urban centers and consisted of scattered rural properties.

Instead, it was a royal settlement and a key venue for these festivals.

During Samhain, in particular, Rathcroghan was a hive of activity focused on its elevated temple, which was surrounded by burial grounds for the Connachta elite.

Those same privileged people may have lived at Rathcroghan. The remaining lower-class Connachta communities resided in dispersed farms and descended on the site only for festivals.

At those lively events they traded, feasted, exchanged gifts, played games, arranged marriages, and announced declarations of war or peace.

Festivalgoers also may have made ritual offerings, possibly directed to the spirits of Ireland’s otherworld.

That murky, subterranean dimension, also known as Tír na nÓg (Teer-na-nohg), was inhabited by Ireland’s immortals, as well as a myriad of beasts, demons, and monsters.

During Samhain, some of these creatures escaped via Oweynagat cave (pronounced “Oen-na-gat” and meaning “cave of the cats”).

“Samhain was when the invisible wall between the living world and the otherworld disappeared,” says Mike McCarthy, a Rathcroghan tour guide and researcher who has co-authored several publications on the site.

“A whole host of fearsome otherworldly beasts emerged to ravage the surrounding landscape and make it ready for winter.”

Thankful for the agricultural efforts of these spirits but wary of falling victim to their fury, the people protected themselves from physical harm by lighting ritual fires on hilltops and in fields.

They disguised themselves as fellow ghouls, McCarthy says, so as not to be dragged into the otherworld via the cave.

Despite these engaging legends — and the extensive archaeological site in which they dwell — one easily could drive past Rathcroghan and spot nothing but paddocks.

Inhabited for more than 10,000 years, Ireland is so dense with historical remains that many are either largely or entirely unnoticed.

Some are hidden beneath the ground, having been abandoned centuries ago and then slowly consumed by nature.

That includes Rathcroghan, which some experts say may be Europe’s largest unexcavated royal complex.

Not only has it never been dug up, but it also predates Ireland’s written history.

That means scientists must piece together its tale using non-invasive technology and artifacts found in its vicinity.

While Irish people for centuries knew this site was home to Rathcroghan, it wasn’t until the 1990s that a team of Irish researchers used remote sensing technology to reveal its archaeological secrets beneath the ground.

“The beauty of the approach to date at Rathcroghan is that so much has been uncovered without the destruction that comes with excavating upstanding earthwork monuments,” Curley says.

“[Now] targeted excavation can be engaged with, which will answer our research questions while limiting the damage inherent with excavation.”

Becoming a UNESCO site

This policy of preserving Rathcroghan’s integrity and authenticity extends to tourism.

Despite its significance, Rathcroghan is one of Ireland’s less frequented attractions, drawing some 22,000 visitors a year compared with more than a million at the Cliffs of Moher.

That may not be the case had it long ago been heavily marketed as the “Birthplace of Halloween,” Curley says.

But there is no Halloween signage at Rathcroghan or in Tulsk, the nearest town.

Rathcroghan’s renown should soar, however, if Ireland is successful in its push to make it a UNESCO World Heritage site.

The Irish Government has included Rathcroghan as part of the “Royal Sites of Ireland,” which is on its newest list of locations to be considered for prized World Heritage status.

The global exposure potentially offered by UNESCO branding would likely attract many more visitors to Rathcroghan.

But it seems unlikely this historic jewel will be re-packaged as a kitschy Halloween tourist attraction.

“If Rathcroghan got a UNESCO listing and that attracted more attention here that would be great, because it might result in more funding to look after the site,” Curley says.

“But we want sustainable tourism, not a rush of gimmicky Halloween tourism.”

Those travelers who do seek out Rathcroghan might have trouble finding Oweynagat cave.

Oweynagat is elusive — despite being the birthplace of Medb, perhaps the most famous queen in Irish history, 2,000 years ago.

Barely signposted, it’s hidden beneath trees in a paddock at the end of a one-way, dead-end farm track, about a thousand yards south of the much more accessible temple mound.

Visitors are free to hop a fence, walk through a field, and peer into the narrow passage of Oweynagat.

In Ireland’s Iron Age, such behavior would have been enormously risky during Samhain, when even wearing a ghastly disguise might not have spared the wrath of a malevolent creature.

Two millennia later, most costumed trick-or-treaters on Halloween won’t realize they’re mimicking a prehistoric tradition — one with much higher stakes than the pursuit of candy.

#Rathcroghan#Connaught#County Roscommon#UNESCO World Heritage#Samhain#Imbolc#Bealtaine#Lughnasadh#Tír na nÓg#Oweynagat cave#Ireland#remote sensing technology#Birthplace of Halloween#Halloween#Royal Sites of Ireland#Halloween tourism#Medb#Oweynagat#Iron Age#Irish history#archaeological site

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

92 notes

·

View notes

Text

It’s always “oh, Geonosis, where they manufactured weapons during the Clone Wars”

And never

“Oh, Geonosis, home of Padme Told Anakin She Loved Him National Park and Monument”

#LISTEN in-universe Star Wars characters I know literally none of you know what happened between Anakin and Padme there#but THAT IS NO EXCUSE#this is a UNESCO galactic heritage site#show some respect#padme amidala#anakin skywalker#anidala

135 notes

·

View notes

Text

Church of the Holy Trinity.

This is one of the oldest churches in Berat. Easily accessible, the church is located in the historic Mangalem neighborhood in Berat, on the southern side of the Berat Castle.

The chapel is from the Byzantine era and was built during the 14th century.

27 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A view of the Kon-dō of Tōshōdai Temple in Nara City, Japan.

#Buddhism#Ganjin#Ganjin Wajo#Japan#Nara#Ritsu sect#Tang Dynasty#Tōshōdai-ji#Unesco#World Heritage Site#travel#唐招提寺

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hill of Crosses

Lithuania

#landscape#landscape photography#black and white#black and white photography#bw#bw photography#crucifix#crucifixes#cultural heritage#hill#pilgrimage site#religious#religious site#cross#crosses#statues#unesco#unesco world heritage#unesco site#interesting perspective#photographer on tumblr#original photography#original photographers#original photography on tumblr#Kryžių kalnas#Kryziu kalnas#Hill of Crosses#Šiauliai#Lithuania#Lietuva

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kölner Dom

Cologne, Germany

#photographers on tumblr#architecture#art#churches#windows#cologne#germany#cathedrals#kölner dom#cologne cathedral#köln#vertical#original photographers#original photography#gothic#unesco world heritage site#world heritage

219 notes

·

View notes

Text

“In Holy Baptism, we are not merely ‘joining the Church,’ nor are we merely ‘washing away our sins.’ Holy Baptism is not a rite of membership. Rather, Holy Baptism is being plunged into the death of Christ (Romans 6:3) and raised into the likeness of Christ’s resurrection. Believers are given a Cross to wear as part of their Baptism – a token to remind us that our new life is nothing other than living in union with the Crucified Christ.”

~Fr. Stephen Freeman

(Photos © dramoor 2015 Neonian Baptistry 5th century, Ravenna, Italy)

#Orthodox Christian#Neonian Baptistry#Ravenna Italy#travel#Fr. Stephen Freeman#Holy Baptism#photography#photographers on tumblr#Scriptures#Lord Jesus#UNESCO World Heritage Site#mosaics#ancient Christian monument

87 notes

·

View notes