#matter of britain

Text

"I am Sir Launcelot du Lake, King Ban's son of Benwick, and knight of the Round Table." Illustration by N.C. Wyeth from p. 38 of The Boys' King Arthur, published by Scribner in 1922.

#art#art history#N.C. Wyeth#illustration#Sir Lancelot#Lancelot du Lac#Knights of the Round Table#Arthurian legend#Arthurian mythology#Arthuriana#Matter of Britain#American art#20th century art

426 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yniol shows Prince Geraint his Ruined Castle by Gustave Doré

#gustave doré#art#yniol#geraint#arthurian#enid#enide#alfred tennyson#castle#ruins#idylls of the king#alfred lord tennyson#tennyson#matter of britain#britain#british#knight#knights#chivalry#chivalric romance#mythology#castles#europe#european#ruin#lord alfred tennyson#magical#architecture#spiral staircase#spiral stairs

301 notes

·

View notes

Text

Celtic mythology/Arthurian legend : King Arthur - Arthur is the legendary king of Britain, he reigns in Camelot and counts on many knights of the Round Table such as Lancelot, Yvain, Perceval as his vassals. His wife is the Queen Guinevere, daughter of Leodagan. He's the wielder of the magical sword Excalibur.

#moodboard#aesthetic#mythology#matter of britain#celtic mythology#arthurian literature#king arthur#arthurian mythology#arthurian legend#arthur pendragon

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝖄𝖔𝖚𝖓𝖌 𝕸𝖊𝖗𝖑𝖎𝖓 𝖆𝖓𝖉 𝕹𝖎𝖒𝖚𝖊 (𝐌𝐞𝐫𝐥𝐢𝐧, 𝟏𝟗𝟗𝟖)

#Merlin#Merlin 1998#miniseries#mythic history#Nimue#Matter of Britain#Daniel Brocklebank#Agnieszka Kozon#fantasy

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

just watched King Arthur (2004) and while the movie has a meh plot, it has an incredible aesthetic and makes me want to write on the Matter or Britain so bad

here's the reason that got me to watch it : siwe

#king arthur 2004#king arthur (2004)#mads mikkelsen#matter of britain#hannibal extended universe#my thoughts#siwer says

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

None of this would have happened if Guinevere had just entered a poly relationship with Arthur AND Lancelot

#something something lancelot has two hands#matter of britain#king arthur#arthur pendragon#guinevere#gwenhwyfar#lancelot#thoughts#funny

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

And another Knight Of The Round Table for Gods Of Earth. Meet Lamorak! He's relatively obscure so I imagine he's insecure and hoping to make a name for himself

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

traytore knyght

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vivien and Merlin (1874) by Julia Margaret Cameron

Photographic illustrations for a new edition of Tennyson's Idylls of the King, a recasting of the Arthurian legends.

#Vivien and Merlin#julia margaret cameron#photography#Photographer#Vivien#Merlin#xix century#victorian#victorian age#Alfred Tennyson#Idylls of the King#Albumen silver prints#arthurian legend#Henry Hay Cameron#matter of britain#lady of the lake#Spell#king arthur#knights of the round table#the round table

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cold winter: King Arthur

KING ARTHUR

Category: Arthurian legend / Matter of Britain

Ah, King Arthur… THE central protagonist of the wave of medieval texts known as the “Matter of Britain”. He is so important to this Matter that it is even alternatively known as the “Arthurian myth”. And yet, King Arthur, despite being known by everybody, will have several dozen descriptions depending on who you ask. He is in the image of his own legend: throughout the texts, the cultures and the centuries he put on numerous different faces…

I) The primitive King Arthur

The roots of king Arthur, as those of his entire “myth”, lies in Welsh literature and Welsh mythology. King Arthur first appeared in literature in two Latin texts: Historia Brittonum (The History of the Britons, between the 9th and 11th centuries) and Annales Cambriae (Annals of Wales, between the 10th and 13th century). Or rather these two works are the first textual mentions of Arthur as a historical figure – both being works of history. The Annales Cambriae mentions Arthur twice: it lists the “year 72” (516 AD) as being the year of the Battle of Badon, “in which Arthur carried the cross of Our Lord Jesus Christ on his shoulders for three days and three nights and the Britons were victors” ; and the “year 93” (537 AD) as the Strife of Camlann, “in which Arthur and Medraut (Mordred) fell and there was death in Britain and in Ireland”. As for the “Historia Britonnum”, it presents Arthur as a “dux bellorum” (war leader/military commander) who fought twelve battles alongside the kings of Britain against the invading Saxons: the first at the mouth of the river Glein, the second to fifth above the river Dubglas, the sixth above the Bassas river, the seventh in the forest of Celidon, the eight at the fortress of Guinnion (and it is there that he “carried the image of Holy Mary ever virgin on his shoulders”, which put the “pagans” to flight, “and through the power of Our Lord Jesus Christ and through the power of the blessed Virgin Mary his mother there was great slaughter among them”). The ninth was at the City of the Legion (Caerleon), the tenth on the banks of the rivers Tribruit, the eleventh on the mountain Agnet, and the last on mount Badon (there Arthur was said to have killed 960 men all of his own in one charge, “as in all the wars he emerged as victor”).

Now… when I say those were the two first apparitions of Arthur, it is unexact. Arthur existed before, and was hinted at or talked about in various other older texts – but it was under his more “primitive” shape, the “original” folkloric figure of Arthur that was shared by both the Welsh in England and the Breton in France. This wide and old tradition depicted Arthur not as a king (as the above texts explains), but as a military leader of the Britons who battled against the Anglo-Saxons as they tried to invade Britain in the aftermath of the fall of the Roman Empire. A great and exceptional warrior without peer or rivals, he was presented as the defender of Britain – from both internal and exterior threats, from both natural and supernatural foes. On top of the Saxons, he was also said to have battled, hunted or killed various monsters and supernatural beings: witches, giants, dog-headed men, dragons… Some tales describe him as living in the wilds with a group of faithful companions who are all warriors with superhuman or unnatural abilities (some even seemingly being former Celtic gods) ; and he seemed to have a strong connection with the Welsh version of the Otherworld, “Annwn”, from either his wife and weapons coming from there, to a story depicting him besieging the fortresses of the Otherworld to obtain their treasures and/or free their prisoners. “Arthur the Blessed” was seen as an embodiment of valour, a hero great warriors could never hope to rival ; as for his entourage, it was implied he had a father-son relationship with Uther Pendragon (though it was only hinted at in certain texts), and while sometimes listed as the leader of two-hundred men, his most prominent and faithful companions were Cei (future Kay) and Bedwyr (future Bedivere). He also appears in another tale (Culhwch and Olwen) as a friend and cousin of the hero Culhwch, who he helps won the hand of the titular Olwen, by assisting him in a series of seemingly impossible tasks, from obtaining belongings of otherworldly rulers to the hunt of giant supernatural boars. And it is explained in the text that while Arthur is ready to help Culhwch in any way, and even lends him his six best men for his duties, there is one thing he will never do: it is lend him his sword, Caledfwlch (future Excalibur).

Beyond these distinctive Celtic/pagan texts, and before the two Latin sources above, Arthur also appeared in some early Latin and Christian texts – the “vitae”, texts retelling the life of saints. In the “Life of Saint Gildas”, the titular saint was living in Scotia as a faithful and loyal subject to Arthur, but his 23 brothers rose up against the “rightful king”, most notably his eldest brother Hueil who would frequently raid from Scotland the rest of Arthur lands – to the point the king had to kill him. However Gildas managed to forgive Arthur, and in exchange Arthur accepted to undergo a penance for the murder of the saint’s brother. Later Gildas arrived at the city of Glastonbury and there discovered a feud between king Arthur, who was besieging the city, and Melvas, the Somerset king, who had abducted and raped Guinevere, Arthur’s wife. The saint arranged peace between the rulers by having Arthur abandon his siege and Melvas return Guinevere to Arthur. Arthur also appeared in “The Life of Saint Cadoc”, where the titular saint puts under his protection a man who killed three of Arthur’s warriors. Arthur demands as a “wergild” (man-price, a compensation for a man’s death) a herd of cattle that the saint delivers, but as soon as Arthur takes the animals they turn into bundles of ferns.

II) The English King Arthur

All of the above was the “primitive” form of Arthur – but the Arthur as we know today originates from one very specific author, and one very specific text. Geoffrey of Monmouth, a Welsh cleric, and his “Historia Regum Britanniae” (The History of the Kings of Britain, 1136), a supposedly historical (but in truth much more fictional/legendary/folkloric) account of all the British kings, from Brutus (legendary “first British king, descendant of the Trojan/Roman hero Aeneas) to Cadwallader (king of Wales at the end of the 7th century).

Monmouth included Arthur in his list, and created him as the character we know today. Descendant of Constantine the Great and son of Uther Pendragon, Arthur was conceived when Uther (with Merlin’s magic) tricked Igerna (Igraine, wife of Gorlois duke of Cornwall) into sleeping with him at Tintagel. Arthur succeeded to his father at the latter’s death, when he was just fifteen – he underwent a series of battles against the Saxons, the Picts and the Scots, conquering Ireland, Iceland and the Orkney Island, building what is known as the “Arthurian empire”. After twelve years of peace, Arthur expanded to Norway, Denmark and the Rome-controlled Gaul, eventually leading to a battle against Rome itself. Arthur and his three closer men, Kaius (Kay), Beduerus (Bedivere) and Gualguanus (Gawain) vanquished the emperor Lucius Tiberius in Gaul, and would have marched on Rome if Arthur hadn’t heard that his nephew Mordredus (Mordred), that he had left to rule Britain in his stead, had married his wife Guenhuuara (Guinevere) and taken his throne. Arthur returned to Britain, and in a final battle against Mordredus on the river Camblam, he killed his nephew but was mortally wounded in turn. He left his crown to Constantine, before being taken to the otherworldly island of Avalon – to be there healed of his wound, and never be seen again.

This story is the foundation on which all of the Arthurian myth was formed. You have everything there: Uther as Arthur’s father, Guinevere as his wife, Merlin as the wizard-counsellor, Mordred as his final enemy, and even Excalibur (in its primitive form of “Caliburnus”).

III) The French King Arthur

Monmouth’s text became MASSIVELY popular and led to many texts expanding or talking about the Arthurian legend, but after this first wave a second important point shifted the Matter of Britain around: the “French Arthurian tales”. Aka Chrétien de Troyes’ various Arthurian novels, which in turn caused a new wave of Arthurian text and traditions in the 12th and 13th centuries. In the Chrétien de Troyes story, interestingly the focus of the tales aren’t on Arthur himself – who becomes just a background character. Chrétien de Troyes added several new elements of focus and importance in the Arthurian myth, such as Lancelot or the Holy Grail, and due to focusing more on the “knights of the Round Table” that surround Arthur, the characterization of the king changes quite a bit. As we follows the adventures of Percival, Gawain, Galahad, Ywain or Tristan, Arthur… does nothing. While before he was a great military leader, a monster-slayer and a ferocious warrior, in this new tradition he becomes an inactive and even some would say “lazy” king. He is still a glorious figure renowned in the Arthurian world and a supreme authority no one would ever dare contest, but from physical prowess, military power and active exploits, Arthur’s qualities shift towards wisdom, dignity, a patient and balanced temper – at the cost of him appearing seemingly… apathic. Weak. Feeble. Barely reacting to the events around him while everyone else goes on adventures, or always retiring from the story for one reason or another – sometimes even depicting Arthur as nodding off after a feast and having to sleep while everybody else stays awake. The Chrétien de Troyes story also introduced the idea of an adulterous love between Lancelot and Guinevere, making Arthur a royal cuckold. A true decline of the hero in the time of the romances.

Up to the early 13th century, most of the Matter of Britain (if not all) was told in verse (from Chrétien’s novels in verse, to Marie de France’s lais). Starting with the 13th century, we start to have prose texts about Arthur: the Vulgate Cycle, or Lancelot-Grail Cycle. Five prose works that focus almost exclusively on both Merlin’s story and the quest of the Holy Grail, while pushing Arthur in the background. BUT these texts also added a key element to the Arthur legend: the idea that Mordred, the nephew destined to kill him, was also actually his son, born of an incestuous relationship he had with his sister Morgause. Plus, the idea that Camelot was Arthur’s main court and castle also came from the Vulgate Cycle. The tradition around those prose texts also decided to include King Arthur as part of a group of men known as the “Nine Worthies”: nine men who were the perfect example and embodiment of chilvary. Three pagans (Hector, Alexander the Great, Julius Caesar) ; three Jewish (Joshua, David and Judas Maccabeus), three Christians (King Arthur, Charlemagne, Godfrey of Bouillon).

IV) The late King Arthur

The wave of the French texts, both verse and prose, came to an end by a full return to England: in the late 15th century, Thomas Malory wrote and published “La Morte d’Arthur”, a retelling of the entire Arthurian legend as build up by the previous centuries in one single text, that became MASSIVELY popular and became the new foundation for the Arthurian myth in England. However King Arthur’s popularity and figure slowly died out alongside the Middle-Ages – unable to resist to a Renaissance that praised and focus mostly and chiefly on Greco-Roman culture, rejecting everything deemed too “medieval”. Up until now, the various texts linked to Arthur were considered as either fully or semi-historical, and everyone agreed that he must have been an historical figure – but by the 16th century people opposed fiercely this idea and rejected Arthur’s tales as pure and entire fiction, complete inventions, and in return they disgraced the entire Matter of Britain from any kind of true “legitimacy” or “interest”. The Arthurian legends were never completely erased – for they were too much part of the culture of several countries and nations – but they lost their prominence and importance: it wasn’t taken with any seriousness, sometimes reserved as folktales and fairytales for children, other times reinvented as comedies and parodies ; and when they were treated seriously, the Arthurian tales were just used for political messages or political allegories (mostly about the politics of the English monarchy, or as reflections of its various kings). After all, King Arthur represented a “golden age” of Britain – he was the greater ruler of England, the “king of kings” who built an empire that crumbled only after his death. Many kings of England aspired to be associated with this figure – to the point Henry VIII himself had a personal “Round Table” built for him!

- - - - -

But to have a true “rebirth” of the Arthurian myth, we will have to wait a few more centuries. Just like King Arthur is said to wait or sleep forever in an otherworldly location, ready to come back to save England whenever it would be in trouble, the Arthurian legend stayed dormant throughout the Renaissance before waking up in the 19th century.

You had a conflagration… 19th century was the century of medievalism, of Romanticism, of the Gothic revival, and they all sought to know more about and revive the Arthurian myth and romance. Malory “Le Morte d’Arthur” was reprinted in 1816 (when its last edition was 1634), the Arthurian time with its knights was paralleled with the Victorian time and its gentlemen, king Arthur became a source of inspiration for many poets (such as Alfred Tennyson) and the Matter of Britain became the prime subject of the painters known as the Pre-Raphaelites. The craze even went beyond Europe, in the USA thanks to Mark Twain’s famous “A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court”…

But unfortunately the World Wars would seriously damage the reputation of the Arthurian myth and cause a mass rejection of the idea of chivalry – one would have to wait until the 50s to see Arthur return to the stage, with works such as T. H. Whites “The Once and Future King”, later adapted by Disney as “The Sword in the Stone”, or Marion Zimmer Bradley’s “The Mists of Avalon”.

King Arthur’s figure is a vast, complex and difficult one to explore in its globality, since each time he has been reinterpreted differently: an otherworldly hero, a messianic king, the pure and golden embodiment of chivalry and knighthood, or a symbol of a great man succumbing to his weakness and falling for his own faults… But my seasonal series are just to provide introductions and starting points, so enjoy this brief recap and if you are interested, go look in the world for more Arthur! Gosh knows the media are now FLOODING us with king Arthur content.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Piety: The Knights of the Round Table about to Depart in Quest of the Holy Grail, William Dyce, 1849

#art#art history#William Dyce#mythological painting#Arthurian mythology#Arthurian legend#Arthuriana#Matter of Britain#medievalism#Pre-Raphaelite#Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood#pre-raphaelisme#British art#Scottish art#19th century art#Victorian period#Victorian art#watercolor#Scottish National Gallery

146 notes

·

View notes

Link

My first audio commission!

Composed and arranged by Sam Yung.

Artwork by Dracona_Arts.

Feel free to leave a like or comment if you want but please do not repost! All rights reserved.

@warsofasoiaf

@cynicalclassicist

To read the first draft of Scotland’s Heir for free, click here.

To buy the final draft of Scotland’s Heir and more, click here.

P.S. Reposting is NOT the same thing as reblogging!

#art for mistland#music#piano#piano solo#arthuriana#scotland#tales from mistland#eugenius#eugenius iii#knights of the round table#camelot#matter of britain#arthur pendragon#king arthur#succession#scottish royalty#scottish history#scottish mythology#scottish legends#music for mistland

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Celtic mythology/Arthurian legend : Lady of the Lake called either Nimue or Viviane, enchantress, sometimes foster mother/protector of Lancelot. Her lake is said to be located in Broceliande and she is associated with Excalibur. She often gives it to Arthur in various versions of the legend. It's also said Merlin felt in love with her and taught her magic.

#lady of the lake#enchantress#viviane#nimue#moodboard#aesthetic#fairy#excalibur#king arthur#lancelot#mythology#matter of britain#celtic#arthurian legend#arthurian mythology#arthurian literature#celtic mythology

31 notes

·

View notes

Note

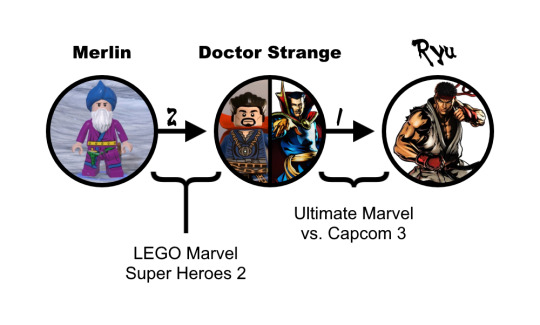

merlin the wizard?

Merlin has a Ryu Number of 2.

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Spear's first year #3: Rich research, circular as the seasons

What sources did I use to develop and research SPEAR? A post about the circular nature of research into an era that can seem to exist in the liminal state between myth and history.

An imaginary moment in which three seasons coexist: blossom in spring, green green grass of summer, and the falling leaves of autumn—blending and never-ending, like research.

Image description: A book, Spear by Nicola Griffith, standing upright in the grass under the trees. Against it lean an enamel pin, sized to look like a shield, and a large boar spear. A small hedgehog noses through the…

View On WordPress

4 notes

·

View notes