#or even outright doing away with it. batman was also written before the concept of him not killing was added to his character

Text

I dunno man I feel like most statements along the lines of ‘Batman isn’t REALLY x, he’s y’ don’t hold much water because usually, there’s a pretty good chance a number of writers over the years have written him as x, you just didn’t like it or think it doesn’t count for some reason.

For example ‘Batman isn’t REALLY a good parent, he’s actually a bad parent’, when Batman has been written as a good parent by a number of writers, and has, in addition, been written as realizing that he’s screwed up with his children and resolved to fix it by even more. At the same time, stating ‘Batman isn’t REALLY a bad parent, he’s actually a good parent’ is also incorrect, because Batman has been written as a bad parent by a number of writers, either intentionally or not; in addition, the pattern presented by the tug-of-war between writers who believe he should be a good parent and writers who don’t has, over the years, created an unintentional pattern that strongly resembles that of an abusive relationship. So, stating he is a good parent is inaccurate and dismisses a bunch of his canon writing, but stating he is a bad parent also dismisses a bunch of his canon writing and the intentions of the authors that wrote him.

The secret here is realizing that Batman has had so many writers over the years that it’s practically impossible to find a universal truth about him beyond the basic premise and maybe very, very basic characterization keystones. Writers with different beliefs about both the character and the world at large have written him in accordance to their worldview, and sometimes that worldview will align with yours, and sometimes it won’t.

Like, at this point, Batman is more an idea than he is a character. He is the bare-knuckled fight against injustice, but what ‘injustice’ is depends heavily on your worldview, as does what ‘bare-knuckled’ and ‘fight’ mean. Batman has been interpreted in dozens of different ways over the years, and singling out a few of those as the True Batman is largely arbitrary and dependent on your personal taste and belief in what the character should be. The only ‘objective’ measurement you could apply here are the old Golden Age comics, and I think most fans can agree that measuring modern Batman comics by how faithful they are to the Golden Age comics is, more often than not, a little ridiculous.

For the record, I do think that arguing about what Batman should be matters; if right-wing assholes use the character as a mouthpiece for their worldview we can and should critique that, but not because it’s ‘OOC’, but because the worldview espoused by those right-wing assholes is harmful and shitty. Batman should be a good parent, not because it’s ‘OOC’ for him to be a bad parent, but because having your paragon of justice be a child abuser is pretty shitty. Etc.

I don’t really have anywhere specific to go with this, I just think it’s a little strange when people try to view Batman as a character with a clear-cut characterization, rather than a concept that many people have approached in different ways over the years. Can that concept be mishandled? Sure. But it’s usually mishandled for reasons a bit more substantial than ‘a previous writer wrote it differently’.

#part of me feels like it's a cop-out to say#'batman isn't really a character so much as a concept and he can rarely ever be truly ooc'#'because he's been written by so many different people that practically any interpretation of him has canon back-up'#but at the same time. when you have a decades long history as one of the most well known pop culture icons of our time#i do think you kinda stop being a character and start being more of a concept#this post was inspired by a lot of stuff but the thing on my mind rn is conversations about why batman doesn't kill#and a lot of people being like 'saying batman doesn't kill because he thinks it'd turn him into an unstoppable killing monster is wrong!'#which. isn't true. that's a take many writers have on his character.#you may not like you or think it's stupid or whatever but. it's an interpretation of the no-kill rule with canon backing#and for that matter. even 'batman doesn't kill' is kind of up in the air with many writers taking a more relaxed stance on that#or even outright doing away with it. batman was also written before the concept of him not killing was added to his character#like. with a character with a history as long an profilic as batman. shit's complicated i feel#bruce wayne#my posts#infodumping

206 notes

·

View notes

Text

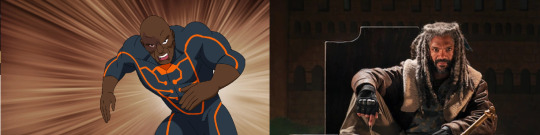

“Invincible”, Season 1 (2021) Review

Somehow both very cool and very fucking stupid :D

About

Created and written primarily by Robert Kirkman (principle writer for The Walking Dead comic and TV show), this Young Adult cartoon basically synthesizes a number of comic book characters (e.g., Superman, Batman, Green Lantern, Hellboy, Wonder Woman, Gambit) and tries to balance their heroism with cynical twists and dark realities. It's an exercise like Brightburn (2019) in that it mirrors existing comic writing all too closely in order to make violent twists. The cool stuff arrives pretty much immediately. You can tell right away that the physics have some level of realism, and it quickly gets serious because of this. The easy comparison would be to The Boys (also by Amazon, also about violent heroes, and also very well-produced). So, if you like The Boys (2019–), you'll probably like Invincible only a little less.

(( Some spoilers but nothing too specific ))

Wrong Focus

But, the stupid stuff comes from the same error that the Kick-Ass movie (2010) made: it focuses on the wrong person(s). In Kick-Ass, the error was focusing on.. well.. "Kick-Ass", an irredeemable loser and waste of screen time. Invincible makes the same mistake, focusing on.. well.. "Invincible", a (so far) irredeemable loser and waste of screen time. So, despite its virtues, this show cannot escape that it made the decision to go for the Young Adult viewing demographic. It reminds me of Alita: Battle Angel (2019) in that way too: some very cool adult concepts ruined by the dramatic devices of unrepentant teenage stupidity and irrelevance. I didn't even like that stuff when I was a teenager, though Jordan Catalano gets a pass.

Main Cast and Characters

The supporting characters were also very stupid. The most annoying was definitely Amber Bennett (voiced by the otherwise cool Zazie Beetz from Deadpool 2 (2018) and Joker (2019)),

who is supposed to be attractive somehow to Mark Grayson ("Invincible", voiced by Steven Yeun, who played Glenn on The Walking Dead)

despite the fact that she constantly judges him, fails to understand him, often fails to give him any kind of benefit of the doubt, and continues to scowl at him and be hurtful towards him even when she has information that should change her outlook towards him. And because she is part of the love triangle shared between herself, Invincible/Mark, and "Atom Eve"/Samantha (voiced by the awesome Gillian Jacobs from Community (2009–2014)),

audiences simply have to bear with it that Amber's annoying character will be present and wasting time until Mark can realize that Amber is in fact toxic and that Eve actually understands him and can improve him in more positive directions. That love triangle should have been a 20-minute distraction, but I'm guessing that it will eat up a season or two more, especially if the writers become cowardly and fail to change things for fear of messing up a perceived "winning" formula. In my ideal story line, they would skip ahead 10 years, drop the teen drama, the love triangle, and the stupid jokes and have Invincible and Eve paired in defense of Earth, with the main tension being from their worry that the other would be horribly gored in front of them during lethal fights against cosmic enemies ;)

Aside, I am aware of Amber’s motivation for being a bad person, I just think her justification is not based in understanding, empathy, and a regard for the gravity of Invincible’s situation. In a strict political sense, Invincible should not commit a lie of omission by keeping her in the dark about his identity — even if for the “noble lie” reason of protecting her — but in a real sense, he is a fucking teenager who just developed his super powers. For her to pretend that he should reveal his entire identity to her — a potentially transformative and even dangerous decision — after a few months of teenage romance paints an absurd portrait of her mind. It does, however, align her with Omni-Man, because where Omni-Man forces Invincible to become an adult in the fighting sense (pushing with full force early on), Amber forces Invincible to become an emotional adult by getting him to understand that toxic people such as herself need to be given boundaries — and he needs to learn to clearly delineate and communicate his real desires. By knowing that he does not want Amber, people who regiment his free time, or people who do not suit him, for instance, he can realize why Eve was an obvious decision: Eve understands, can make time when they have time, and will let him find his decisions. Part of a coming-of-age story tends to be realizing what one actually wants, and Invincible’s hesitation in telling Amber his identity shows that he does not truly want her. This separates Invincible from, say, Spider-Man, who avoided telling Mary Jane his identity not because he did not want her but because he wanted at all costs to protect her.

The next most annoying character has to be Debbie Grayson (voiced by TV-cancer Sandra Oh and who luckily was not animated to look like the real Sandra Oh and who should have been voiced instead by Bobby Lee due to Lee's successful MadTV parody of Sandra Oh).

Debbie basically fills the role of Skyler in Breaking Bad, except that Debbie's character tends to be slightly more understanding before her inevitable and toxic Skyler-resentment and undermining behavior. Despite having an 8-episode arc of change, Debbie's character flips too quickly and lacks the empathy and Omni-Man motive-justifying that would make her interesting (the comic's development may vary). For instance, if she refused to believe that Omni-Man meant his own words, that would make her empathetic and perhaps virtuous even if misled, but instead she dropped their "20 years" of understanding after viewing Omni-Man in action, which makes her appear shallow, easily manipulated, and unsympathetic. That was a definite "Young Adult" genre move because it shows immaturity by the writers to break apart a bond of 20 years so quickly. Mediocre teens might accept such a fissure because their lives have not yet seen or may not comprehend that level of time, but adults know that even long-standing and problematic relationships (which, beyond the lie, Omni-Man's and Debbie's was not shown to be) take a lot of time to break — even with lies exposed.

Omni-Man

The biggest show strength for me was of course Omni-Man, who in a success of casting was voiced by J.K. Simmons in a kind of reprisal of Simmons' role as Fletcher from Whiplash (2014).

The Fletcher/Omni-Man parallel shows through their being incredibly harsh but extremely disciplined and principled, forcing people to become beyond even their own ideal selves (this via Omni-Man's tough-love teaching of Invincible — comically, Omni-Man was actually psychologically easier on Invincible than Fletcher was on Whiplash's Andrew character). Despite the show's attempts to villainize Omni-Man, he, like Fletcher and also like Breaking Bad's Walter White, becomes progressively more awesome, eventually representing a Spartan will, an unconquerable drive, and a realistic and martial understanding of a hero's role.

To the show's credit, while it wrote Omni-Man to be outright genocidal and from a culture of eugenicists (again, Spartan), they could not help but admire him and his "violence" and "naked force" (for a Starship Troopers reference), giving him a path to redemption. That redemption comes in part because — despite the show's attempt to be often realistic and violent — its decision to be directed at young adults via dumb jokes, petty relationship drama, the characters’ reckless lack of anonymity and security in their neighborhood (loudly taking off and landing right at the doorstep), and light indy music also made the portrayed violence far less literal. With a less literal violence, the real statement becomes not that Omni-Man really did kill so many people (though he certainly did kill those people within the show's plot) but that he was symbolically capable of terrible violence but could be reformed for good. That's the shortcoming with putting violence under demographic limitations. If it's a PG-13 Godzilla knocking down cities, the deaths in the many fallen skyscrapers don't matter so much (the audience will even forgive Godzilla for mass death if it happens mostly in removed spectacle), whereas if it's Cormac McCarthy envisioning a very realistic fiction, every death rides the edge of true trauma.

By showing light between the real and the symbolic, it is much easier to identify and agree with Omni-Man. For instance, when Robot (voiced by Zachary Quinto of Heroes and the newer Star Trek movies)

shows too much empathy for the revealed weakness of "Monster Girl" (voiced by Grey Griffin), the audience may have thought, "Pathetic," even before Omni-Man himself said it. And this because Omni-Man knows that true and powerful enemies (including himself) will not hesitate to use ultra-violence against these avenues of weakness. "Invincible" can make his Spider-Man quips while in lethal battles, but he does so while riding the edge of death — something that Omni-Man has to teach Invincible by riding him to the brink of his own.

Other Cast/Characters and Amazon's Hidden Budget

It was impressive how many big-name actors were thrown into this — a true hemorrhage of producer funding. Amazon has so far hidden the budget numbers, perhaps because they don't want people to know that the show (like many of its shows) represents a kind of loss-leader to jump-start its entertainment brand.

Aside from those already mentioned, the show borrows a number of actors from The Walking Dead (WD), including..

• Chad L. Coleman ("Martian Man"; "Tyreese" on WD),

• Khary Payton ("Black Samson"; "Ezekiel" on WD),

• Ross Marquand (several characters; "Aaron" on WD)

• Lauren Cohan ("War Woman"; "Maggie" on WD)

• Michael Cudlitz ("Red Rush"; "Abraham" on WD)

• Lennie James ("Darkwing"; "Morgan" on WD)

• Sonequa Martin-Green ("Green Ghost"; "Sasha" on WD)

There were also connections to Rick and Morty and Community, not just with Gillian Jacobs but also with...

• Justin Roiland ("Doug Cheston"), who voices both Rick and Morty in Rick and Morty,

• Jason Mantzoukas ("Rex"),

• Walton Goggins ("Cecil"),

• Chris Diamantopoulos (several characters),

• Clancy Brown ("Damien Darkblood"),

• Kevin Michael Richardson ("Mauler Twins"), and

• Ryan Ridley (writing)

That's a lot of overlap.

They even had Michael Dorn from Star Trek: TNG (1987–1994) (there he played Worf) and Reginald VelJohnson from Family Matters (1989–1998) and Die Hard (1988), and even Mark Hamill. Pretty much everyone in the voice cast was significant and known. Maybe Amazon got a discount for COVID since the actors could all do voice-work from home? ;)

Overall

Bad that it was for the Young Adult target demo but good for the infrequent adult themes and ultra-violence. Very high production value and a good watch for those who like dark superhero stories. I have heard that the comic gets progressively darker, which fits for Robert Kirkman, so it will likely be worth keeping up with this show.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Should Hiro Mashima die?

My answer is no.

Though, this isn't about actually killing Hiro Mashima. Kinda got you with the title, though, huh? (This was originally going to be titled “Is Hiro Mashima dead?” and released on his birthday. You’re welcome.)

This post is about a widely debated topic of analysis known as the "death of the author." I've talked about this a few different times in passing in a few posts over the years. You could argue that this belongs in my series rewriting Fairy Tail and I considered placing it there. However, I feel that it's better that I keep this detached from that series. This topic concerns criticism of any series. Naturally, being a Fairy Tail blog, I plan on engaging this with the context of Fairy Tail's author being dead or not, hence the title. Still, this is helpful to think about for analysis of plenty of other series.

Again, though, my answer is still no.

Let's start with the origin of this term. The term comes from an essay by Roland Barthes called "La mort de l'auteur". Use your best guess as to what that translates to. I highly encourage you to read the essay as it's pretty short. It's about six or seven pages, depending on the version. There are three main points to his essay.

Creative works are products of the culture they come from and less original than people expect.

The idea of the author as the sole creator and authority of creative works is fairly modern.

The author's interpretation of a work shouldn't be considered the main or only interpretation of a work.

Of these three points, I'm sure you recognize the last point. But first, I want to talk about the other points. I believe it is important to understand the arguments being made as a whole.

The first point should be fairly uncontroversial. The vast majority of creative works use established language, tropes, and elements to create a new thing. I wouldn't go as far as Barthes does in this regard. Not to mention, this is somewhat weird to know considering his third point. However, I agree that creative works should be considered products of the culture and genre they come from.

The second point is a bit trickier for me. To be clear, the point is true. You only have to look at various cultural mythologies as an example. There isn't a single version of the Greek myths. There are several versions and interpretations of the various stories and myths.

Even recent popular fictional characters have had several different interpretations. This is especially true with comics. There have been multiple different Batman interpretations, Spiderman runs, and X-Men teams that fans love. Fans even love and appreciate numerous forms of established characters like Frankenstein's monster and Sherlock Holmes. So, as a consumer and critic of art, I can understand this.

My problem is as a creator of art. I understand this being contentious when it comes to something like religious myths. But, if I create something, I want to get the credit for it. I want people to love my music or writing. But I also want people to recognize me for my skill in crafting it.

This is true even if you hold to the first point Barthes made. Even if you believe that no art is truly unique, isn't the skill of synthesizing the various tropes and influences around a person worthy of credit in and of itself?

Then again, I am not without bias in this. Barthes says that the modern interpretation of the author is a product of the Protestant Reformation. As a Protestant myself, I get that my background plays no part in my view of this. Barthes also blames English empiricism and French rationalism, but personal faith is the biggest influence on me that Barthes lists.

That being said, there's also something Barthes completely misses in his essay. In the past, stories were passed down by oral tradition. As the stories were passed down from generation to generation, they slowly evolved and became what they are known today. Scholars today can gather a general consensus of what a story was meant to be and some traditions were more faithful about passing traditions down than others. However, you can't always tell the original author of a mythological story the same way we know who gave us stuff like the Quran or the Bible.

As time passed, stories were written down. With this, it was easy to share single versions of a story and identify its creator. We know who made certain writing of works even before the 1500s. For example, we have the Travels of Marco Polo and Dante's Inferno and know their authors. We could tell the authors of works were before the Protestant Reformation.

By the way, the Reformation happened to coincide with one of the most important inventions in human history: the printing press. Now you can easily make copies of an individual's works and you don't have to rely on word of mouth to share stories.

I can't stress how important an omission this is. The printing press changed the way we interact with media as a whole and might be the most important invention on this side of the wheel. And yet Barthes doesn't even mention as even a potential factor in "the modern concept of the author"? In his essay about understanding written media? That’s like ignoring Jim Crow in your essay about Birth of a Nation bringing back the KKK.

Now, we get to the final point. The author's original intentions of their works are not the main interpretation. This is understood as being the case after they create the series. Once the work is written and sent into the public, they cease to be an authority on it.

It's worth recognizing how this flows from the other two points. Barthes argued that works of fiction are products of their culture and our current understanding of an author is fairly modern. Therefore, the interpretation of the reader is just as valuable as that of the author. As Barthes himself wrote, "the birth of the reader must be at cost of the death of the author."

At best, this means that a reader can come away with an interpretation of a work that isn't the one intended. With Fairy Tail, my mind goes to the final moments of the Grand Magic Games. My view of Gray's line "I've got to smile for her sake" has to do with romantic feelings for Ultear. I don't know of a single person who agrees with this. Mashima certainly hasn't come out and affirmed this as the right view.

It's good to recognize that a work can have more meanings behind it than the ones intended by its creator. Part of the performing process is coming to a personal interpretation of a work. In many cases, two different performances will have different interpretations of the same work, neither of which went through the creator's mind. At the same time, both work and are valid.

That being said, there is an obvious problem with this: readers are idiots. Not all readers are necessarily idiots. But enough of them are idiots. The views of idiots should have as much weight as that of the creator. Full stop. Frankly, I maintain that idiots are the worst possible sources to gauge anything of note. (At the very least, policy decisions.)

I know this as a reader who has not been alone in misunderstanding a work. I know this as an analyst who has had to sift through all kinds of cold takes on Fairy Tail. (Takes that are proven wrong simply by going through it a second time. Or a first.) And I definitely know this as a creator who has to see people butcher my works through nonsensical "interpretations."

At the same time, the argument Barthes made comes with an important caveat. He also argued that works are the products of the culture and surroundings of the author. Barthes isn’t making the argument that author’s arguments don’t matter.

As far as I can tell, Barthes doesn't take this to mean that those influences are worth analyzing. Doing so would be giving life to the author. However, there should be some recognition that a creative work didn't come to exist out of nowhere. There's a sense in which Fairy Tail didn't just wash up on the shore chapter by chapter or episode by episode. It came to be as part of the culture it came from.

Now, you'll never guess what happened. Over the years, the concept of "death of the author" lost its original intent. Nowadays, people usually only care about the third point. "Death of the author" is only brought up to dismiss "word of God" explanations of work, after its release. I'd venture to guess that most people using the term casually don't know anything about its roots. I honestly don't know how Barthes would feel about this.

I can understand what might fuel this view. A writer should do their best to write their intended meanings in a work. It would be wrong of a writer to make up for their poor writing after the fact. I don't love Mashima's "Lucy's dreams" explanation for omakes. I know Harry Potter fans don't love the stuff J.K. Rowling has said over the years.

At the same time, my (admittedly Protestant) understanding of "word of God" and "canon" is that they have the same authority. After all, the canon IS the word of God. It is a small section of what God has said, but it isn't less than that.

Of course, it's worth recognizing that nearly every writer we're talking about isn't even remotely divinely inspired or incapable of contradiction. This understanding should cut two ways. An author should never contradict their work in talking about it. Write what you want and make clear what you want to. On the other hand, writers can't fit everything they want to in a work. I'll get to this soon, but their interpretation should be treated with some value.

By the way, people will do this while throwing out the other arguments made by Barthes in the same essay. People will outright ignore the culture and context that a work comes from in order to justify their views. Creators are worshiped and praised for their works or seen as the sole problem for the bad views on works.

What worries me most about this modern interpretation of "the death of the author" is its use in fan analysis. People seem to outright not care about the author's intent in writing a story. They only care about their own interpretation of the work. Worse still, people will insist that any explanation an author gives is them covering up their mistakes. Naturally, this often leads to negative views of the work in question.

This is just something I'll never fully understand. It's one thing if you don't like something. If you don't get why something happened, shouldn't your first move be to figure out what the author was thinking? Instead, people move to the idea that it makes no sense and the writer's a hack.

If all of this seems too heady, let's try to bring this down to earth. Should Hiro Mashima die so that his readers can be born?

Hiro Mashima is one of many mangakas who were influenced by Akira and Dragon Ball. He considers J.R.R. Tolkien to be one of his favorite writers. Monster Hunter is one of his favorite game series. He's even written a manga series with the world in mind.

It would make sense to look at Fairy Tail purely through this lens. You could see Fairy Tail as a shonen action guild story. Rather than seeing the guild as a hub for its members, Fairy Tail's members treat those within it as family. Rather than focusing on one overarching quest, the story is about how various smaller quests relating to its main characters threaten their guild. Adopting this view wouldn't necessarily be an incorrect way to engage with the series. (Mind you, I haven’t seen this view shared by many people who “kill Mashima”.)

Though, there's more to Fairy Tail than the various tropes that make it up. If you were to divorce Fairy Tail entirely from its creator, you'd miss out on understanding them. There are ways Mashima has written bits of himself into the series. Things that go farther than Rave Master cameos and references.

My favorite example is motion sickness. I often think back to Craftsdwarf mocking motion sickness as a useless quirk Dragon Slayers have. It turns out that its origin comes from his personal life. Apparently, one of his friends gets motion sickness. He decided to write this as part of his world.

This gets to the biggest reason I don't love "death of the author" as a framework for analysis. I believe the biggest question analysts should answer is why. Why did an author make certain decisions? You can't do this kind of thing well if you shut out the author's interpretation of their own work. Maybe that can work for some things, but not everything.

I've had tons of fun going through Fairy Tail and talking about it over the past seven years. More recently, I've been going through the series with the intent to rewrite the series. I've made it clear multiple times in that series that I'm trying to understand and explain Mashima's decisions in the series. I don't always agree with what I find. However, trying to understand what happened in Fairy Tail is very important to me.

It's gotten to the point that I love interacting with Mashima's writing. I talk about EZ on my main blog. I can't tell you how much fun I've been having. I'll see things and go "man, that's so Mashima" or "wow, I didn't expect that from him." HERO'S was one of my favorite things of last year and I regularly revisit it for fun. It's the simplest microcosm of what makes each series which Mashima has made both similar and distinct.

Barthes was on to something with his essay. I think there should be a sense where people should feel that their views of the media they consume are valid. This should be true even if we disagree with the author's views on the series. But I don't know that the solution is to treat the author's word on their own work as irrelevant.

There's a sense where I think we should mesh the understandings of media engagement. We recognize that Mashima wrote Fairy Tail. There are reasons that he wrote the series as we got it and they're worth knowing and understanding. However, our own interpretation of the series doesn't have to be exactly what Mashima intended. We can even disagree with how Mashima did things.

I know fans who do this all the time. They love whatever series they follow, but wish things happened differently. Fans of Your Lie in April will joke about [situation redacted] as well as write stories where it never happens. You love a series, warts and all, but wish for the series to get cosmetic surgery, or take matters into your own hands.

And who knows? It's not as if fans haven't affected an author's writing of a series. Mashima's the perfect example. I've said this a few times before, but Fairy Tail has gone well past its original end at Phantom Lord (or Daphne for the anime fans). Levy rose to importance as fans wanted to see more of her.

Could Mashima have done that if we killed him?

Before the conclusion, I should mention another way “death of the author“ comes up. People will invoke “death of the author“ to encourage people to enjoy works they love made by messed up people. Given everything we’ve said up to this point, that’s obviously not what should be intended by its use. For now, though, I do think that we can admit that we like the works of someone even if we don’t agree with everything they did as a person. (Another rant for another day.)

In Conclusion:

“Death of the Author” is an imperfect concept, but it’s not without its points. I don’t think we should throw out the author’s intent behind a work. However, we should be able to have our disagreements with the author’s views without killing them.

#fairy tail#hiro mashima#death of the author#i'm back#and what a way to return#i've been meaning to do this forever#fav

15 notes

·

View notes

Note

Imagine that you were put in charge of a modern, high-budget, well-written Animorphs TV series. What changes to the plot/characters/world would you make while adapting it? (Books that you'd skip, arcs that you'd rearrange, things you would add or outright alter...)

[Important caveat: I have ZERO experience in set design, directing, editing, camerawork, or any other processes involved in TV production, unless we’re going to be super generous and count the bit of scriptwriting and stage-acting I did in high school. Ergo, these ideas might make no sense in practice.]

Animate it. I would much much prefer to see an anime-style show to a live-action one for a handful of different reasons:

Battle scenes, morph sequences, and alien appearances wouldn’t be constrained by budget realities. Although we’ve come a long way from AniTV’s practical effects, in 2019 Runaways still minimizes Old Lace (the sentient dinosaur) and struggles with her somewhat less-than-convincing appearance while she’s onscreen. I’d like to see real-looking battles between exotic animals and highly unusual aliens. I’d like to see Ax portrayed as a deer-scorpion-centaur with no mouth who also has complex facial expressions. I’d like taxxons and hork-bajir that match their descriptions in the books. CGI for a moderate-budget TV show can’t do that yet.

The characters’ appearances could match their descriptions in the books. I don’t really care about AniTV’s Jake having blue eyes or Marco having short hair. I do care about the fact that Cassie is described as short, chubby, dark-skinned, natural-haired, and androgynous in self-presentation… whereas AniTV’s Nadia-Leigh Nascimento is (through no fault of her own and 100% the fault of Nickelodeon) none of those things. I’d like to see all of the characters drawn in a way that matches their canon racial heritage, and voiced with actors of those ethnicities as well. For bullshit marketing reasons of bullshit, that’s not as likely to happen in a live-action show.

I’d want the show to convey the frequent mismatches between characters’ physicality and their personalities. It’s an important motif of the books. It’s part of the reason that Tobias has been claimed by the trans* community. It’s a major plot point, lest new viewers think that the vice principal of the school is actually trying to kill his own students. It doesn’t come off in AniTV, for all that I commend them for even trying (casting Shawn Ashmore’s twin as controller-Jake, portraying Chapman as straight out of Stepford), just because the nature of controller-ness and nothlitization are difficult to convey literally. Animation has a lot of tricks, from deliberately distorted drawings to screensaver-like “mental space,” that can actually convey concepts like mind control or body dysmorphia pretty well — Alphonse in Fullmetal Alchemist and Aang in Avatar the Last Airbender great examples of body-mind mismatch and multiple consciousnesses in one body, respectively.

Use a cold open for every episode. I am a sucker for Batman cold opens or any other opening scenes that pick up in the middle of the characters’ everyday lives, because they work so well to convey that there is a crapton of life happening outside of the plot of any given episode. Several Animorphs books (#9, #14, #35, #41, #51) open this way, to great effect, and I love the way that it gives us slices of life we might not otherwise see (morphing to cheat on science homework, completing entire offscreen missions, having dinner with the family) and help build these characters’ worlds outside of individual episode plots.

Introduce James sooner (and have better disability narratives). There are several aspects of Animorphs’ social justice consciousness that age okay (Rachel shutting down Marco’s constant flirting) or not well at all (Mertil and Galfinian). One important way the series could update Animorphs is through having canon disabled characters like James, Mertil, and Loren have bigger roles and not resorting to kill-or-cure narratives. Maybe James could come in sooner and form a Teen Titans West-esque team with the other Auximorphs so that he and Collette and the others could be recurring supporting characters with unique plotlines. Maybe Loren could still gain morphing power, but remain blind and brain-damaged so that the hork-bajir need to work with her to figure out accommodations while sleeping rough.

Modify Jake’s and Cassie’s parents to account for the contemporary setting. The fact that the kids so often disappear all afternoon or even overnight without anyone worrying just wouldn’t translate to a contemporary reimagining of Animorphs. Tobias and Ax are each other’s only family on the planet whereas Marco’s dad and Rachel’s mom are both overworked single parents. Jake’s family, however, and Cassie’s…

Cassie’s parents are so freaking cool in canon that they would definitely start to worry if Cassie went for an entire “weekend at Rachel’s” without answering any texts or calls. Maybe there could be some scenes with them talking about how they have this super-mature responsible daughter whom they can trust not to get into trouble even if she does hate cell phones, but oh well because they’re not big on technology either.

Jake’s parents are… less cool, but they still try their best. The show might explain their lack of concern about either of their disappearing kids through upping the hippie factor from his mom, maybe until she practices Free-Range Parenting. (Why yes, it is true that Jake’s family would have the necessary privileges to get away with free-range crap while Cassie’s family would not, because yes it is the case that black families have been arrested for leaving kids alone for 10 minutes while white families are allowed more passes under the law. Yes, that is a steaming pile of racist bullshit.) The other way it could go is by having Jake’s parents completely checked out, which could get in the way of plots like #31 that hinge on them genuinely caring about their kids, but could also introduce an interesting dynamic if it partially parentifies Tom.

Include at least one Rashomon plot. The TV series would by necessity lose the first-person narration, with all its brilliantly subtle shades of bias and misinterpretation. One way to try and bring that back in would be to convey the same events from multiple points of view with subtle differences in the way that each person perceives what happened. This could happen somewhere in the Visser One plot, with Rachel interpreting the scene as a straight Animorphs-vs-yeerks battle, while Visser One interprets it as Visser Three incompetently sabotaging her as Animorphs ruin her life, while Marco interprets it as a struggle to protect his mom and also save his friends, while Visser Three interprets it as the andalite bandits flagrantly plotting with Visser One, while Jake interprets it as Marco going off the rails from stress… and the only witness who has a sense of what actually happened is Eva. Other possibilities abound.

Start with a plan to make one episode per book… and modify as necessary. There are areas of the series I’d like to see expanded (#50 - #54 covers a lot of ground in relatively little space) and areas that I think could afford to be compacted (#39 - #44 feature a whole lotta nothin’). But instead of adding or discarding an entire book, I think you could spread out many of the plots by simple virtue of TV shows not being constrained by first-person narration.

Certain books just wouldn’t get straight-translated today anyway (#40, most notably). I don’t think any books are so bad or useless that they couldn’t be modified into decent television episodes.

The ramping-up that leads to open war happens mostly in the background of #44 - #51, but a bunch of scenes with just controllers talking to each other could go into that process in a lot more detail. This content could help fill out plots like #44 and #48 that frankly don’t have a lot else going on.

The entire plot of Visser happens over a nonspecific period of time between #30 and #45, so instead of getting one book we could get an entire running Yeerk Empire subplot with major consequences for the main plotline.

Similarly, the andalites’ decisions happen mostly offscreen but have major consequences for the Animorphs. The consequences for the Electorate after the events of #38 could also run for a whole subplot that sets up their decision to nuke Earth in #52.

The biggest absence from the last couple books is Rachel. Her last book is a friggin’ dream sequence, she acts out of character in #52 especially, and the narration order cuts off directly before giving her one last book. It wouldn’t be necessary to add an entire episode just to rectify this oversight, when #51 could still be Marco-centric but also show her and Jake on their sabotage mission, and #52 could have the same rough plot but with a few scenes between her and Tobias thrown in for good measure.

Anyway, maybe the various Chronicles could be a handful of Doctor-lite episodes where the Animorphs themselves are incidental and Elfangor or Aldrea has the helm. Maybe the events of the Chronicles could come out organically over the course of the show, for instance by expanding the memory-dumps Tobias gets in #1 and #33 or having Jara tell Dak’s story in #13 or #23. The Megamorphses, on the other hand, could pretty easily just occur as regular-series episodes, albeit possibly as two- or three-parters.

Lean into the comic-book aesthetic. Animorphs is written very much in the style of a graphic novel, from its “teens with superpowers save the world from aliens” plot to its heavy use of onomatopoeia. Even the use of hypertext symbols around thought-speak hearkens back to the comic book convention of using pointed brackets around alien languages to convey translation. The show could homage this motif through having dramatic transformation sequences, “uniforms” of multicolored spandex the kids use to morph, an opening credits sequence that emphasizes the power of each animal, and other superhero-comic elements throughout.

Have the violence be consequential. To keep the examples from earlier: in Fullmetal Alchemist, as well as in Avatar, characters that get hurt stay hurt. A character getting shot or stabbed is portrayed as a potentially life-changing event. Characters’ injuries do not disappear between episodes, and even alchemy and waterbending are not portrayed as total fixes. Characters scar, they become disabled, they spend entire episodes in recovery, they accrue trauma, and they do not shrug off life-ending injuries. Animorphs helps to justify the idea that six kids could (mostly) survive (most of) an entire war against a friggin empire through making the protagonists nigh-unkillable thanks to their healing abilities, but it nevertheless shows that shooting someone will result in that person bleeding and screaming and possibly dying. Having a sci-fi or action show meant for children isn’t actually a valid excuse for portraying violence as cool or funny or inconsequential the way that (Avengers Assemble, Teen Titans, Kim Possible, Dragonball Z, Pokemon, etc.) too many children’s sci-fi/action shows opt to do.

#animorphs#anitv#racism mention#long post#asks#anonymous#animorphs meta#ableism mention#teen titans#avatar the last airbender#fullmetal alchemist#Anonymous

950 notes

·

View notes

Photo

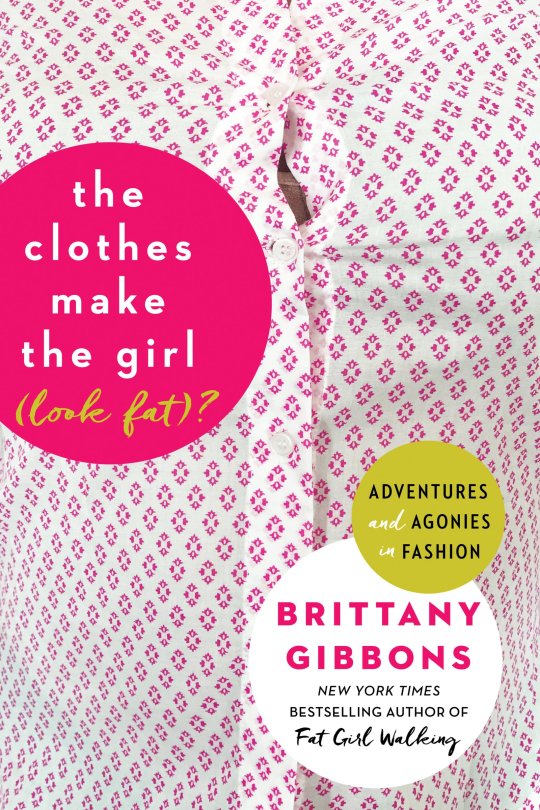

BOOK | The Clothes Make the Girl (Look Fat?): Adventures and Agonies in Fashion by Brittany Gibbons

I have officially confirmed that Brittany Gibbons and I are the same person.

I have read both of her books now and through both of them wrote copious notes that illustrated how she and I share many of the same experiences, attributes, body type, thoughts on certain topics, almost everything plausible that we could have as similarities. Some people will say that they read a book and swear they could have written it themselves. That is me with Brittany Gibbons.

Her sophomore novel, The Clothes Make the Girl (Look Fat?): Adventures and Agonies in Fashion, documents her personal grapples with something every plus-size woman struggles with at some point or another (if not all the time) – fashion. It’s not just trying to find clothes that will fit on your body, period; it’s the mental frustration we face alongside it, like coming to terms with the number that dictates this entire process, and the fact that those numbers when shopping store to store are hardly ever consistent. When a larger woman tells you that the struggle is real, you best believe the struggle is real. And Brittany Gibbons, thank the Lord, approaches these and other topics with wit and pure honesty about every battle she has experienced when it comes to the clothing on her back. If you thought her first book was legit, her second is right up there with it.

In true memoir style, The Clothes Make The Girl follows a general chronology of her life. We begin more or less in her adolescence and conclude with post-baby body. Along the way, Brittany not only cracks jokes about her exploits – a comic relief I really grew to appreciate – but she also constantly reminds readers that there is nothing wrong with their body. I wrote down so many quotes that were positive affirmations – reminders that FAT. BODIES. ARE. NORMAL. BODIES. Right away from the prologue, “Real women [...] are not defined by their curves, thigh gaps, or chest size.”

Furthermore, shortly thereafter in the Introduction, another spectacular truth: “We hold jobs, we go out with friends, and we date. We do normal human activities and feel a healthy desire to do them in clothes that make use feel confident and beautiful and are reflective of our personalities.” Let’s be real, not many of us plus-size ladies have personalities rooted in elastic banded sweatpants and Looney Tunes (not out in public, anyways).

Before I started reading The Clothes Make the Girl, I noted that I was already at a comfortable, confident standpoint with my body. Granted the current fashion scene has produced far more plus-size fashion than in years past and I can actually say that I have numerous outlets within which I can easily find stylish digs for my size 18 body... I wondered what the experience of reading this book would feel like for someone who wasn’t already at a body positive stage in their life. The beauty of this book, however, was that even though I am at that stage, I was able to find a renewed sense of self-assurance in myself, proving that it is a quality piece of literature for women (or any plus-size person) to read. It’s not solely for those starting their journey; it can be a tool for everyone feeling discouraged or in a rut when dealing with their bodies and fashion.

Despite every topic covered in The Clothes Make the Girl, I believe the most poignant section of the entire book is an intermission of sorts titled “You Have My Permission To Hate Yourself.”

Let me repeat that louder for the people in the back:

You have Brittany’s permission to hate yourself.

What sets Brittany Gibbons apart from other authors who tackle body positivity is that, sure, many will tell tales of their own personal demons, but I don’t recall any author or novel off the top of my head that outright told readers that it was okay to hate yourself and your body, and that it was normal to do so. “You don’t owe anyone shit,” Brittany says. “And only you get to decide how you feel about [your body] today.” Hell yassss, Gibbons. Hell yes. And some days, you’re allowed to be unhappy with it. That doesn’t mean you have to beat yourself up over it, or go on some extreme diet to change it.

While the major struggle in plus-size fashion lies in finding quality clothes for our double-digit bodies, another that Brittany touches base on that makes her literature all the more relatable is what happens when the clothes (especially pants) are finally found and worn. Many of us whom have never seen the light of a thigh gap are very familiar with the concept of chub rub and the sorrow of eventually rubbing holes through the inner thighs of our favorite bottoms. “I’ve buried more jeans than there are Batman movies” is a beyond relevant statement from this book. We try to salvage them as much as possible, but its occurrence and their ultimate disposal is inevitable. I’m glad to see its inclusion in The Clothes Make the Girl.

There were times in this book, just as there were in her first memoir, where she lost me a little (those pregnancy and babies chapters) but that doesn’t negate the fact that her logic and wisdom about plus-size lifehood were still present with flying colors. The Clothes Make the Girl is an excellent representation of life in plus-size fashion, and how rough it truly is. Brittany Gibbons touched on many of, if not all, the things I felt were important, especially in regards to legitimate ups and downs of body/fat positivity.

I give her major credit for extending her memoirs while also touching on a very specific topic; depending on said topic, I might consider that a difficult task. My only qualm might be that I felt the book ended a bit abruptly.

I don’t consider this to be a 5-star novel like her first (which still remains my only 5-star to date), but it was still a good quality read. I will always enjoy Brittany’s comical nature in the face of adverse subject matter and our seemingly unending list of resemblances. I’m sure as long as she continues to publish, I will absolutely continue to appreciate and enjoy her work.

FAVORITE EXCERPTS

"[...] Even Anna Wintour isn't dressed like Anna Wintour all the time."

"... Don't let anyone ever make you feel bad for liking clothes and doing your hair and wearing makeup. You are allowed to enjoy yourself in this life..."

"... We also hold jobs, we go out with friends, and we date. We do normal human activities and feel a healthy desire to do them in clothes that make us feel confident and beautiful and are reflective of our personalities."

"I am a normal being with a body that fits into some things and not into others."

"My insecurities came from other people telling me I should have them."

"Loving your body is about being comfortable in your body, and only you get to set the parameters of that, only you get to decide what it looks like, and only you know where your finish line is."

"The sexiest women I know are sexy because they feel sexy for themselves first."

"Your priority in this life is you."

"What you are feeling about yourself right now is fine and normal and allowed."

"... Take a shower and start over knowing that ninety percent of the people out to judge you are inside your own head."

"... You need to realize that you don't owe anyone shit. our body is yours, and only you get to decide how you feel about it today."

"Buy yourself clothes that fit. They may not be the size you think you should be, but who cares?"

"Thunder Thighs is a ridiculous insult. As if having thighs as loud and as powerful as thunder was a bad thing... That basically makes me an X-Man."

"When your jeans don't fit, buy a bigger pair. Larger jeans are worth the dinners with your best friends, the gelato during a semester in Italy, sleeping in on Sundays if you are tired, and a movie night on the couch with someone you love."

"Never apologize for your body. Ever."

"I won't hide my stomach to keep up some illusion that only thin bodies are beautiful."

"Body love is hard work."

ABOUT BRITTANY GIBBONS

(from the back cover)

Brittany Gibbons writes the award-winning humor blog BrittanyHerself.com and runs the Facebook group CurvyGirlGuide.com. She gave a 2011 TED talk on the reinvention of beauty and is the author of New York Times bestseller Fat Girl Walking: Sex, Food, Love, and Being Comfortable in Your Skin... Every Inch of It. Her writing has been featured in the New York Times, Huffington Post, Redbook, Woman's Day magazine, Marie Claire, Los Angeles Times, The Stir, and Babble, among many other publications and sites. Brittany also hosts a weekly Google talk show called Last Call Brittany and the weekly podcast Girl's Girls. Brittany lives in Ohio with her husband and three children.

The Clothes Make the Girl (Look Fat?):

Adventures and Agonies in Fashion by Brittany Gibbons

Publishing | Date | Pages

MY RATING:

★ ★ ★ ★ ✩

I'm fairly certain that any book Brittany Gibbons publishes, I will enjoy it. Many of the notes I took with The Clothes Make the Girl were because I agree with her statements so much. Our ideas, body types, etc. are so similar, it's almost as if I could have written this book myself. She may have lost me a little bit with the baby-centric life and fashion (as did also happen with her first book), but her logic and wisdom were still there.

I wasn't sure how well I could get into this book at first (it took me a long time to get a good pace started), but it really is an excellent representation of life in plus-size fashion. And the truth is that it is rough. But she touched on all the major points that I felt were important. The best overall part of this book was absolutely the chapter/intermission having permission to hate yourself and your body. Not everyday is as easy as the previous... and that's okay.

This was a good extended memoir while also touching on a specific topic. That's not always easy to do for my tastes in literature. However, I did feel that it ended a little abruptly. While I don't think this is a 5-star book like her first, it was still a good quality read. Especially as I once again go through a shift in my own personal style, and of course, the every day occurrences in fashion for a plus-size woman.

#book review#books#literature#the clothes make the girl#the clothes make the girl (look fat?)#the clothes make the girl by brittany gibbons#the clothes make the girl (look fat?) by brittany gibbons#brittany gibbons#advice#memoir#biography#autobiography#novel#reading#read#review#reviews

0 notes

Note

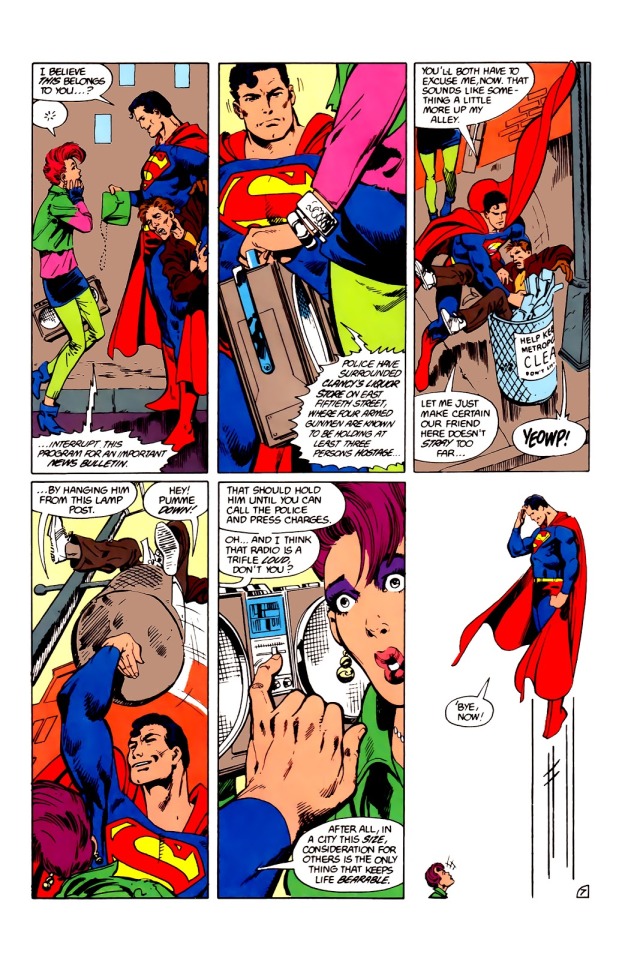

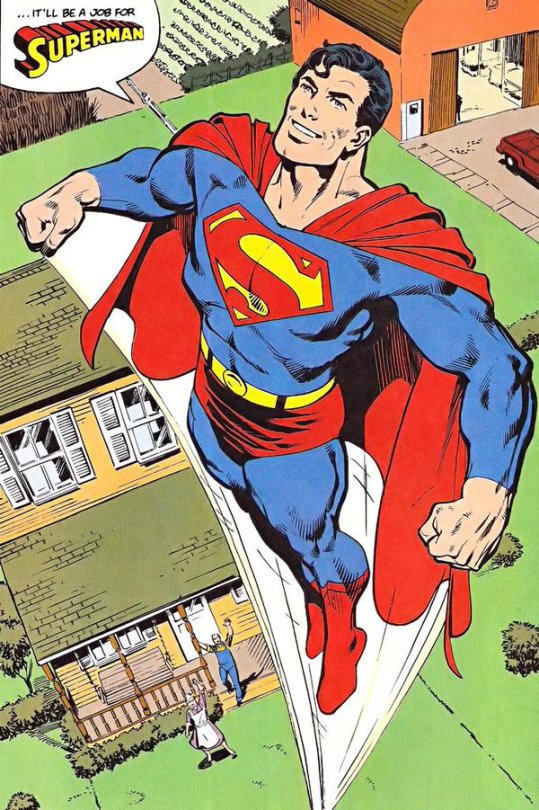

On one level hasn't Byrne's Superman been a smashing success? What other DC character has survived intact since 1986?

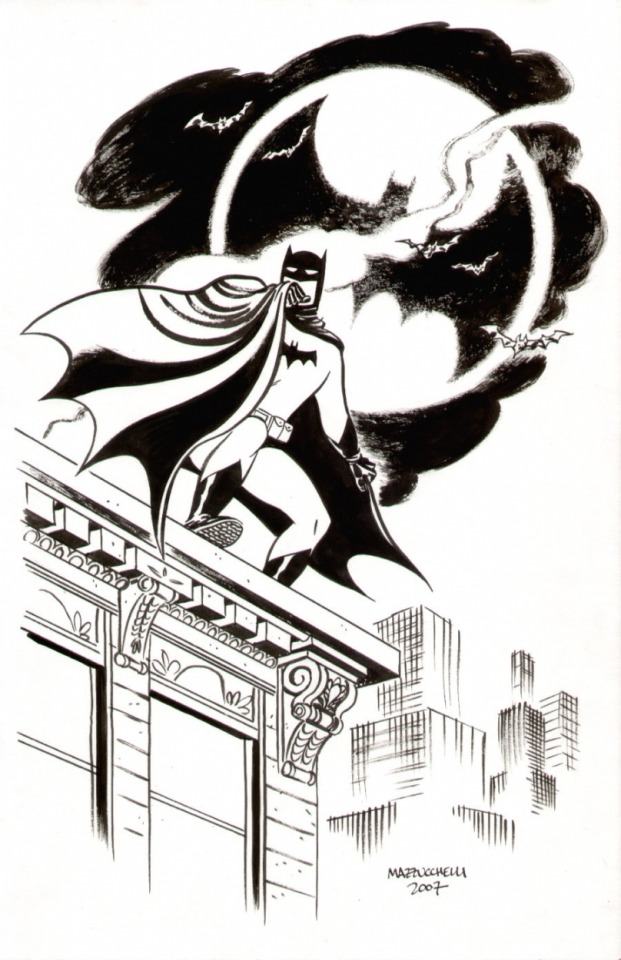

Well…I mean, this dude’s done pretty well for himself since 1986 too, I’d say.

I’d say considerably better, given that it was right around when Byrne revamped Superman that this guy beat him in the public eye now and forever, and people were generally satisfied enough with how he turned out that he’s stayed pretty much the same ever since with only a few tweaks - even the full reboot of the New 52 left him close enough to alone that it had to be retroactively established with Zero Year that anything of substance had been changed about him. Superman meanwhile went in the wake of Byrne’s reimagining from striding across the industry as a colossus, the undisputed most popular and lucrative superhero (and I’d say the most artistically successful as well up to that point other than Swamp Thing, the Spirit, and maybe Daredevil, between Moore’s work and Maggin’s novels), to a wistful kitsch afterthought at best, at worst a ‘mistake’ WB has spent decades and hundreds of millions of dollars trying to correct. Obviously there’s much more to what went wrong there than Byrne’s work - I’ve written about it before - but dispensing with politeness for a second for the sake of directness? I 100% think John Byrne bears the blame for Superman’s diminished state over the years as much as any other one person alive. At minimum, he is the closest there is to an embodiment of the most destructive era for the character.

It’s a funny thing; Man of Steel was actually one of my first comics as a kid, and for years I really did love it. Superman was my favorite between picture books, the animated series and the Flesicher shorts my dad had on tape, and I guess that was the closest I had to a big, weighty story with him (it probably didn’t hurt either that my first version of his origin as a kid, The True Story of Superman, was based on it). Batman and Spider-Man eventually took the lead though, and when I really got into Superman again as a teenager and he really became my favorite character, and I reread that in light of what I had come to appreciate about him? It just left me cold. The middle chunk is still a solid little run of superhero adventure comics - even if they get a little checklist-ey - and they’re absolutely gorgeous between Byrne, Giordano, and Ziuko, but the beginning and end, how they establish him as a character, built a foundation I am absolutely willing to say has just not worked, even aside from Superman’s entire journey to heroism turning out to be “boy, I sure did ignore your moral lessons for the first 17 years of my life, mom and dad. I suddenly am The Best Person now though, so I’ll be Superman in arbitrarily-presented secrecy until I reveal myself to the world in plain streetclothes”.

I’ve talked plenty in chunks before about a lot of what didn’t work for me here, but hitting the high points:

* Streamlining the Superman/Clark divide to the point of near-nonexistence with a more ‘normal’ Clark makes sense in the abstract as a way of making him more down-to-earth and understandable, but in practice it removes an indescribable degree of character tension and definition, and also makes Clark relatively boring because he’s exactly like Superman but not doing Superman stuff.

* In an attempt at incorporating Christopher Reeve’s charming, all-loving take, one that hadn’t really been seen in the comics up to that point, Byrne settled on a guy with a decidedly limited emotional scope. While trimming out some of the neuroticism of the Silver Age version was probably a good move, what we ended up with was a Superman who, pleasant as he may have been, didn’t have much range to him beyond calm beneficence, affection, determined seriousness, and the odd moment of sadness/shock where appropriate. He may not have been outright stiff, but he definitely came off less as Your Cool Dad so much as just The Dad. Nice, but not really charming. He’s got a sense of humor, but he’s not exactly down with The Kids™ either. Great coworker, standup Joe, but you couldn’t exactly imagine having much of a conversation with the guy.

* It scaled his world to exactly the wrong degree for an ongoing comics version of the character. I may be onboard with a cosmic Superman, but bringing him closer to square one for a total overhaul makes sense. But instead of taking the logical step of bringing him all the way back to near the Golden Age and having him fight ‘realistic’ threats again, he fought the same array of supervillains as ever. So you got neither the catharsis of a champion of the oppressed battling real-world ills or the awe of a godlike superbeing battling unimaginable perils from beyond the stars; instead he was a very strong (but not too strong, that’d be silly) guy in a generic city who fought bad guys and won, and never struggled too hard in that because again, he’s the clean-cut Superman, so you can never show anything getting too intense. Not that it’s impossible to tell satisfying stories with that setup, Mark Millar did great stuff on a similar scale in Superman Adventures with clever adventure stories, but in practice most writers took the easy out of regular villain brawls - an inevitability for something as long-running as comics with creators not being forced to push themselves in one direction or another - and it ended up a worst-of-all-worlds mix in that regard.

* The soap opera approach of those years led to a ton of what’s commonly regarded as the dumbest stuff for the character, and I think led pretty directly to the neverending crossover setup that’s done so much to hobble him over the last decade. And when that approach ostensibly driven by emotional drama was paired with the reduction of internal conflict in Clark himself, I think the attempts at forcing that necessary conflict again while staying in line with how Byrne had established things ultimately led to a lot of the hand-wringing “What does it truly mean…for me to be…a…Superman?” moping of the last twenty years.

* Much like its years-later namesake, this version of Superman pushes a fairly hardline assimilation take on his relationship with his heritage where the place he came from was bad and wrong, and the climax of what emotional journey he has is embracing his status as a real human/American, which cuts out a lot of the idea of him as an alienated figure showing us to accept the strange and different. It also hasn’t particularly aged well in how blatant it is as an 80s Cold War metaphor: there sure is a lot of talk about how the Kents imagined the cold, isolationist, inhuman, deservedly-doomed-to-die place Clark came from might have been Russia.

* It’s the first set of Superman comics to start to internalize in a big way the idea that Superman, or at least most of the mythology of his world, is silly and dumb and need to be fixed, even as creators wanted to bring all the fun old stuff back, squaring that circle by way of making everything either tremendously more boring or infinitely dumber. A square world is stupid, Bizarro’s just a sad grunting Frankenstein who dies in his first appearance now. Invulnerable? That makes no physical sense, so he’s got a forcefield, that somehow totally explains it all. He’s gotta truly be the sole survivor of Krypton now, that’s heavy and realistic, but what about Supergirl? Well, she’s, ah, a fire-angel protoplasmic clone of Lana Lang from a pocket universe. Sure. Also Brainiac’s a carny possessed by/possibly hallucinating the classic villain. And later on, following in those footsteps, Krypto’s from a fake Phantom Zone Krypton, and Kandor has no Kryptonians, and there were no other Kryptonian survivors because of genetic manipulation by a nationalist Kryptonian supercomputer, and the Supermen Red and Blue were electric energy beings brought about to fight the Millennium Giants, and Toyman’s a pedophilic serial killer, and Zod’s a mutant dictator in power armor who absorbs red sunlight and may be in telepathic communion with the original character. Yes, all that’s dribbling fucking idiocy removing every ounce of charm from the basic concepts with almost surgical precision, but at least it’s all quite serious.

I know Byrne’s era has a ton of support - it’s an 80s soap opera comic, those tended to accumulate die-hard fans. I understand it was better from a craft perspective than its immediate predecessors, since the Superman titles had been intentionally kept in a holding pattern (except for Moore’s work) of simple adventure stories as introductory stuff for kids. I imagine the focus on his personal relationships did a lot for people, it introduced a handful of genuinely good ideas (Wolfman’s corporate baron Luthor ended up meshing well with the best of the established take, and him drinking in solar radiation over time to explain his changing powers was inspired, for instance), and this particular brand of smoothed-out clean-cut pleasant superheroism is easy to look back on as a brighter, lighter time. But it was a creative dead zone - just about every major beloved Superman story either came before this period, or after its influence notably started to wane. And boy did it wane: people have been trying to reboot away from this thing constantly, over and over again, restoring every old element Byrne and company discarded. There have been three major origin reboots in the last decade-and-a-half, each farther away from the last, with Mark Waid (one of Byrne’s loudest critics for decades) bringing back the conceptual baseline stuff Byrne had missed in Birthright, Geoff Johns bringing back all the Silver Age mythology he could, and Grant Morrison (who while appreciative of aspects of Byrne’s take, also commented it had a “whiff of prefab plastic smugness”) pulling things all the way back to the Golden Age. And, with absolutely no caveats, Waid and Morrison’s word on Superman carries more weight than Byrne’s ever will. DC’s finally tried going back to Byrne’s version lately to grab on nostalgia dollars, and they’re even rebooting away from that next month less than a year after it began in earnest.

Obviously, Superman’s comics can only have so much impact on his public profile at this point. But Byrne’s ‘clean slate’ constricted possibilities and character, deadened the titles creatively for years, threw the line into a constant state of chaotic push-pull between creators who love essentially two different characters calling themselves Superman, and judging by how Superman’s lagged behind in other media since then, failed to inspire much in those charged with bringing his adventures to a larger audience, poisoning the brand far beyond the people still picking up his regular printed adventures. The film that did bring major aspects of Byrne’s vision to a larger audience in Man of Steel was…well, it was Man of Steel. Love it or hate it, there’s no argument to be made that the world broadly accepted it as an iconic, recognizable take on the character.

And that’s why, petty as it may be, I’ll always smile when I remember that Dick Giordano once pulled Byrne aside to explain to him "You have to realize there are now two Supermen – the one you do and the one we license.“ Still damn good art though.

#Superman#John Byrne#Batman#Christopher Reeve#Bizarro#Supergirl#Brainiac#Krypto#Kandor#Krypton#Eradicator#Superman Red#Superman Blue#Toyman#Zod#Mark Waid#Geoff Johns#Grant Morrison#Dick Giordano#Kinda ranting#Not gonna lie: parts of this were written while very tired#We'll see how it looks when I wake up#Opinion

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

OK so. The treatment of the We Are Robin gang in Batman Secret Files: The Signal #1.

TL;DR: It’s bad and a logical conclusion of the treatment of the gang post-We Are Robin, which as been going steadily downhill.

We Are Robin took great care to develop its team as much as possible; while it showed clear bias towards some select members (mostly Riko and to a lesser extent Izzy), everyone got their own arc and conflicts. None of the characters felt like they existed just to prop one of them up, and all of them felt like they have had lives and stories well before they were introduced on page. Basically: they felt like people.

Duke is the only character who has maintained the spotlight post-We Are Robin, and apparently, writers have taken this as a sign that they should character massacre everyone else. To my knowledge, the first major role post-WAR for any of the former Robin Collective members was Batman & The Signal, with Izzy and Riko, and both of them were shadows of their former selves in that, to the point that, if Duke’s character hadn’t been written with clear knowledge of We Are Robin, I would’ve said that the author just straight up hadn’t read it.

Riko’s characterization in Batman & The Signal is especially abysmal. Riko is portrayed as petty and childish, and overly focused on The Mission(TM) (aka crimefighting), telling Izzy that being Duke’s girlfriend is ‘distracting’ him from The Mission. This makes no sense with her previous characterization; while Riko obviously took being a vigilante seriously, she was portrayed as a dreamer, as well. I’d have to re-read both We Are Robin and Batman & The Signal to give on in-depth analysis on why I think her character is misrepresented in the latter (which I won’t do right now bc it’s Very Late for me), but to my reading, Riko in We Are Robin is quite a compassionate character, and would be unlikely to think that ‘relationships make you soft’ like she seems to in Batman & The Signal. In fact, I’d argue that she’d be infinitely more likely to consider relationships a strength, especially due to her experiences in the We Are Robin team. That, and also, she’s heavily implied to have a crush on Duke and be jealous of Izzy in We Are Robin, so she’s clearly not against Duke having a relationship. Maybe it was intended as an extension of her earlier jelousy, but then, again, she’s not that petty and childish.

Izzy has also been a shadow of her former self for a while now. While I think her characterization wasn’t quite as bad as Riko’s in Batman & The Signal, it lacked any real personality; it feels like you could swap Izzy with any random girl from the street and it would stay essentially the same. Gone are the complex family issues Izzy dealt with in We Are Robin. Her entire character in both Batman & the Signal and now Batman Secret Files: The Signal seems to be ‘Duke’s girlfriend’. Also, she was grossly whitewashed in Batman & The Signal, and while she looks better in Batman Secret Files, she’s still not anywhere close to her original design. If you hadn’t told me that was Izzy I wouldn’t have known by looking at her.

Batman Secret Files: The Signal finally delves into what happened to the rest of the We Are Robin gang after Duke got recruited by Batman, which is a fantastic concept and something I’ve been wondering about! Unfortunately, it’s clearly a transparent excuse to cause problems for Duke.

Dre’s characterization has little in common with what he was like in We Are Robin, and Jax straight up getting put away in Juvie Arkham is a disgrace to his character. If he needed to be a vigilante that bad, he could just??? Be one??? Like I’m sure it’d be harder without Batman/Alfred’s help, but he’s already. Done that. Like he’s already shown that he’s perfectly willing to make his own vigilante persona. Why wouldn’t he just. Do that. It makes no sense!!! No sense at all!!! Except if it is to guilt-trip Duke and provide problems for him, as well as a thin excuse to put Dre and the rest of the We Are Robin gang in an antagonistic role.

Poor Riko is the one whose character assassination is the worst. First of, no clue wtf is up with her powers, I’m assuming I either missed an obvious explenation bc I’m tired, or that it’ll get explained later, and frankly it’s the least of my problems. Riko being resentful of Duke for getting picked by Batman makes NO fucking sense, considering, oh, I don’t know, Riko’s whole entire fucking character in Batman & The Signal. Why would she be resentful of Duke for ‘abandoning’ the We Are Robin gang, but then help him as the Signal??? Why would she go so far as to scold Izzy for having a relationship with Duke???? Riko in Batman & The Signal seemed proud of Duke for having ‘graduated’ (her literal words), not resentful!!! None of this makes any sense with either her We Are Robin character, who was a kind, eccentric dreamer, or the hardass focused-on-the-mission Riko presented in Batman & The Signal. Neither would blame Duke for stuff that’s objectively not his fault, and even if she was resentful of him, she wouldn’t outright fight or attack him over it!! What the hell!!!

This is scattered and not as thought out as it probably should be because, again, I’d have to do some rereads and I’m also super tired right now, but it’s extremely clear that Batman Secret Files: The Signal has, at least so far, absolutely no interest in examining the We Are Robin gang as their own characters. Rather, they are being used to prop up Duke and the plot. This is a massive insult to both their own characters and Duke, since Duke doesn’t need to have his friends reduced to props to have interesting interactions with them. We Are Robin proved that these people work as a team, and that while not all of them might get along that well, they are a family. Duke’s interactions with them are infinitely more interesting if they’re allowed to be their own characters and have a life outside of Duke. That’s usually how character interactions work. Wild, I know.

Stop destroying the characters of the We Are Robin gang!!! Just let them be good characters!!! Damn!!!!

#riko sheridan#isabella ortiz#batman secret files: the signal#wednesday spoilers#duke thomas#my posts#infodumping

25 notes

·

View notes