#recently extinct

Text

leave everything always unbroken

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Tie a string around your finger, so you won't forget...

The Carolina Parakeet was declared extinct in 1939.

Up until just the year before, people were still claiming to have sighted the yellow-headed parakeets in the wild—in the impenetrable depths of Georgia's Okefenokee Swamp; along the Santee River basin of South Carolina, where people still search for the Ivory-Billed Woodpecker to this day—but evidence suggested only escaped, feral species of pet birds, tinged by wishful thinking.

The last definitively identified specimen of Conuropsis carolinensis, a male named Incas, had died at the Cincinnati Zoo in 1918. As it happens, his last home was the very same cage in which Martha, the endling Passenger Pigeon, had spent her final years. 2014, the hundredth anniversary of Martha's loss, brought the publication of a number of new books on the topic of the Passenger Pigeon and even a documentary; the centenary of Incas' death, by contrast, warranted only a handful of mentions of our lost native parrot.

Hardly a hundred years later, our parakeet has faded from common memory—like the fading text on the tags that twine around the feet of the study skins that fill museum specimen drawers, where they should have filled the sky, should have filled roosts in hollow trees, should have filled our backyards; should have filled their lungs with air, and our hearts and imaginations and eyes with the sight of their iridescent green feathers.

The title of this painting is Memory Knot. It is gouache on 18 x 13 inch paper, and is the 9th piece in my series on the extinct Carolina Parakeet. It is also the final piece in the series as originally conceived (though inspiration continues to strike, and this is not the last appearance the species will make in my art).

Please, remember that there was a bird called the Carolina Parakeet. Remember what happened to it. Remember that we are the only ones who can keep it from happening again.

948 notes

·

View notes

Text

Day 4 of January extinct birds - the black mamo (top, also known by other names) and the kauaʻi ʻōʻō (bottom)

Two birds! The hawaiian honeyeaters are the only entire family of birds to go extinct in recent times, and the kauaʻi ʻōʻō is the last (1987) and most famous. The song of the last male was recorded two years after the last female was estimated to have died. Other members of the family have unique striking plumage that the kauaʻi ʻōʻō doesn't, which might sadly be part of why it was able to persist for longer.

I also wanted to add in the black mamo to represent the hawaiian honeycreepers (not the same as honeyeaters!). These birds are similar to darwin's finches in the galapagos where their crazy beak shapes went through drastic evolution. Yes, the honeycreepers are finches! While some species are classified as least concern, most of the honeycreepers are extinct or critically endangered. Hopefully the extinction of the honeyeaters encourages people to focus their attention on the honeycreepers too so they don't suffer the same fate.

sorry for such a sad post! Island birds have really suffered the last few centuries :c

#bird of the day#birds? of the day#bird art#extinct animals#birds#digital illustration#illustration#extinct birds#recently extinct#daily art#passeriformes

549 notes

·

View notes

Text

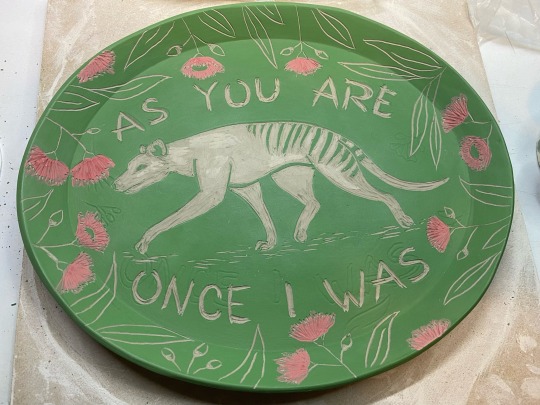

a new thylacine! fingers crossed 🤞🏼 this one doesn’t crack

#reserved#thylacine#thylacine art#extinct species#extinct animals#recently extinct#pottery#ceramics#ceramic#sgraffito#ceramic art#carving#underglaze painting

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

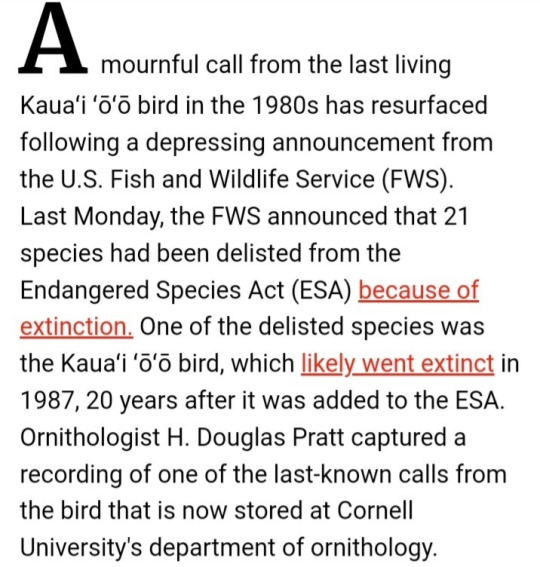

This was quite haunting to read.

#animals#birds#Kauaʻi ʻōʻō#Kauaʻi#hawaii#hawai'i#extinction#extinct animals#extinct species#news#science#zoology#biology#Endangered Species Act#ESA#recently extinct#Putting a bunch of tags in this because I really want this story to be known. It made me so sad.

438 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thylacine. Last Chance on Earth; a Requiem for Wildlife. Roger A. Caras. Illustrated by Charles Fracé. 1966.

Internet Archive

629 notes

·

View notes

Text

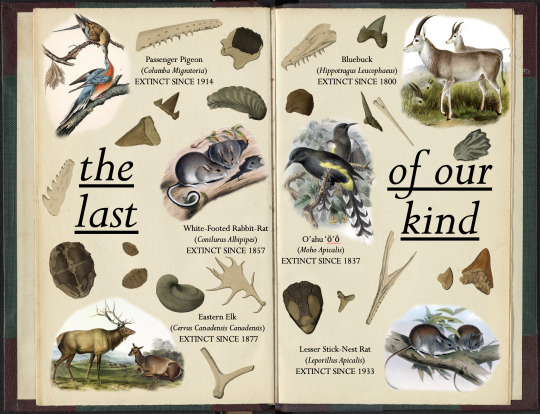

An Account of the First Aërial Voyage in England – Vincent Lunardi // A Pictorial Atlas of Fossil Remains – Gideon Algernon Mantell, James Parkinson, Edmund Tyrell Artis // Potorous Platyops – John Gould // Thylacinus Cynocephalus, Juvenile – Joseph Wolf // Choeropus Castanotis – John Gould // Hippotragus Leucophaeus – Joseph Smit, Joseph Wolf // Hapalotis Albipipes – John Gould // Pyrenean Ibex – Richard Lydekker, Joseph Wolf // Eastern Elk – John James Audubon // Royigerygone Insularis – Gregory Macalister Matthews, Henrik Grönvold // Sceloglaux Albifacies – John Gerrard Keulemans // Leporillus Apicalis – John Gould // Columba Migratoria – John James Audubon, J. T. Bowen // Moho Apicalis – John Gerrard Keulmans // ...Familiar Place – Lucy Dacus

for @artists-ache 💙🌹 📖

#okay so this is pretty different from my usual style#so if you don't like it just let me know and i'm happy to make a new/different edit with the same lyrics!#i was aiming for sort of a natural history/field notes type look#but idk if i achieved it 😅#natural history#extinction#extinct animals#extinct species#recently extinct#extinct birds#fossils#...familiar place#...familiar place lucy dacus#no burden#no burden album#no burden lucy dacus#lucy dacus#rose 🌹📖#request 🥰#art#art history#lyrics#lyric art#tw bones

496 notes

·

View notes

Video

The only known footage of the Laysan ʻapapane (Himatione fraithii) from 1923.

After rabbits were introduced and consumed their nectar sources, the Laysan ‘apapane went extinct alongside the Laysan millerbird and Laysan rail due to a strong storm that hit the island.

[video source]

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Needed to practice birds more, so did a pair of Huia!

#my art#digital art#huia#birds#extinct birds#recently extinct#one of the species im sad i will never see

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Spectacle(d Cormorant) - an informative post about an underrated extinct bird

(Artwork by me. Halfly based on the artwork by Joseph Wolf.)

Just something out of the ordinary from before. I am getting tired from posting all those comics and stuff on here, so here's a repost of my depiction of one of my all-time favorite extinct birds - the life, the moment, the spectacle itself - the spectacled (or Pallas's) cormorant, as well as a bunch of facts about it below this because I care about this bird so much and will protect it with all my life if it still existed.

You may ask, why am I so into this nerdy-looking bird? It's not like it's THAT special or anything - we still have at least 40 other cormorant species alive on earth - 3 of them in the same genus as the spectacled cormorant.

The reason is simple - no one ever talks about it or even has an idea on what it is, even though humans were the sole cause of its extinction. (And believe it or not, cormorant culling IS still a thing, but that's a different story for now.)

(Specimen kept at the Naturalis Biodiversity Center in Leiden, the Netherlands.)

Large, stupid, clumsy, ludicrous in looks. That was how others, including Georg Steller, the discoverer of the bird, described the spectacled cormorant. It was, perhaps, the largest of all cormorants known to exist, rivalling the Galápagos flightless cormorant in length, but was way heavier than the latter. Due to its large size, it was probably flightless, but studies of its wings have shown that it was more likely reluctant to do so due to its lack of natural predators (besides Arctic foxes) while residing in its former habitat - the Commander/Komandorski Islands in Kamchatka Krai of Russia. Occasionally, some of these birds would get lost and end up on the Kamchatka Peninsula, which led to its consumption by the locals.

However, it wasn't until the 1820s when their extinction was hastened. The Russian-American Company started to transfer Unangan (Aleut) people to the islands, and, to no surprise, they found this cormorant easy to hunt. As Steller said on his journey in 1741, the spectacled cormorant was also rather delicious, unlike most other cormorants. Along with how it was abundant on the Commander Islands, this was most likely the exact reason why the Unangan people consumed it whenever they could not catch enough fish to sell or feed their families.

That marked the end of the legacy of the spectacled cormorant. It vanished from the islands and the world in the 1850s, and was never heard from anyone ever again.

(Artwork by J. G. Keulemans.)

The reason why it might have been forgotten by man was probably due to there only being six known specimens of this bird collected (all apparently by the same person, Governor Kuprianof), and only one or two of those specimens are currently up for display in the whole world.

The spectacled cormorant died like the dodo, but unlike the dodo, it was quickly forgotten by the people who caused its rapid extinction. By the time we wanted to care about it, it was already gone.

170+ years have passed. People like me still remember this bird, wanting to do anything to bring it back to life, or just imagining it while it was still in its glory - plummeting into the cold seas to catch a mouthful of fish, as it clumsily swims back to the shore to dry its wings. A beautiful bird that met a rather depressing fate.

#extinct birds#bird art#spectacled cormorant#recently extinct#extinct animals#i can't draw backgrounds#extinction#lineless art#digital artwork#informative post#fact post#bird facts#cormorant#seabirds

240 notes

·

View notes

Text

I was looking through some of my colored pencil sketchbooks, and found this little Quagga friend. A subspecies of the plains zebra, the Quagga used to live in massive herds in South Africa, until it was hunted to extinction by European invaders in the 1800s (some say, before the hunters realized how special it was). Today, there are breeding programs trying to resurrect the Quagga’s phenotype, but our knowledge of the animal’s natural history remains murky. Drawn in colored pencil, 6x7 inches.

207 notes

·

View notes

Text

Durango Shiner

i decided to draw a a Notropis aulidion (Durango Shiner) after seeing AVNJ draw it on stream, i couldnt find anything about colour so i kinda just looked at other species of Notropis to get a general feel

im not too good at drawing small fish yet, the way you render them is slightly different to larger fish due to the differing levels of subsurface scattering

#paleoart#paleontology#digital art#artists on tumblr#digital artwork#palaeoart#digital illustration#id in alt text#sciart#paleobr#fish#fish art#extinct fish#recently extinct fish#recently extinct#Durango Shiner#Notropis aulidion

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

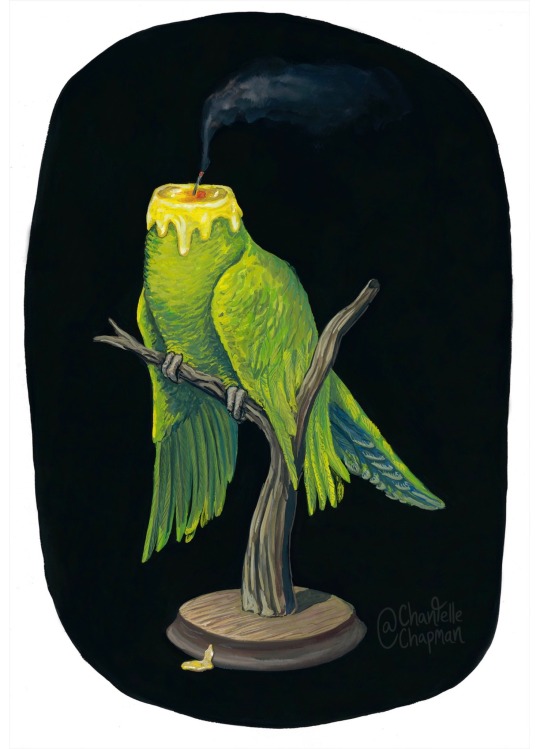

Another from my Carolina Parakeet series, this painting is gouache on 18x24” watercolor paper. It is a particular companion to the previously-posted ‘American Tannenbaum’, and its title is ‘The Etymology of Loss’.

The word ‘extinct’ existed for nearly four centuries before it was applied to the death of a species. Originally a variant of ‘extinguish’, the earliest use of the word can be found in the 1400s, when it was a descriptor for lights that had been doused. Within a short span, its meaning would expand to include the ending of specific family lines (i.e. “the king died without heirs, and his house became extinct”).

The progression from candle to lineage to species seems obvious in hindsight, yet it wasn’t until the early 19th century that the word became synonymous with the loss of an animal—the simple reason for this being, it wasn’t until that point that learnéd-minds accepted that species-death was possible.

According to the prevailing philosophy, the universe had been designed in perfect, unshakable balance, from which no element could possibly be subtracted or altered—much less by the actions of mere humans. (I’ve heard similar reasoning from modern climate change deniers.) The removal of species was an inherently blasphemous concept.

Even as they watched animals like the aurochs and tarpan vanish before their eyes, people assured themselves with the knowledge that more existed…just…somewhere else (after all, wolves had).

(Do you want to know one of my favorite stories from American history? When Thomas Jefferson sent Lewis & Clark on their expedition out west, one of his dearest hopes was that they would discover a living population of mastodons.)

It was the continued lack of any live mastodons, or mammoths, or wooly rhinos, not to mention the reptilian leviathans being uncovered by the burgeoning field of paleontology, that finally tipped the scales of common sense. In 1807, French naturalist Georges Cuvier, who had extensively studied such bones, came out strongly with the assertion that, yes, clearly, species can and do die.

Then began the task of counting the extinguished.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Ghosts in the water.

Another one of my collection of pieces based around the Bramble Cay melomys.

227 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bachman’s Warbler (Vermivora bachmanii).

#bachman’s warbler#extinct animals#extinct species#recently extinct#extinct birds#vintage illustration

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

The lesser bilby (Macrotis leucura), less degradingly known as the yallara by the Wangkangurru people, is one of Australia's many many obscure recently extinct mammals. It was last seen alive by western observers in 1931, although based on First Nations knowledge (and a skull found under an eagle's nest) it appears to certainly have survived at least into the 1960s.

(Image credit: Oldfield Thomas’ Catalogue of the Monotremes and Marsupials in the British Museum)

The yallara was smaller and less colourful than the living greater bilby (M. lagotis), hence its description of as the "lesser" of the two species, but what it lacked in stature it made up for in ferocity. Unlike its larger cousin, the yallara was reportedly very aggressive and feisty, with Hedley Finlayson (one of the few scientists to observe the species in life, and the last) writing that they:

"...completely belied their delicate appearance by proving themselves fierce and intractable, and repulsed the most tactful attempts to handle them by repeated savage snapping bites and harsh hissing sounds, and one member of the party, who was persistent in his intentions, received a gash in the hand three quarters of an inch long from the canines of a male."

Although few observations of the species were made in life and much of their ecology remains a mystery, they may also have been more carnivorous than the living greater bilby. Investigations of stomach contents found large quantities of skin and fur from rodents, with only limited seeds and no insect fragments having been ingested. However, this information only comes from a small sample of individuals, so whether or not the yallara was the most predatory of all modern bandicoots will likely remain uncertain. They also differed in behaviour from greater bilbies by always blocking the entrance to their burrow after entering.

The species was only observed by Europeans in the harsh deserts of north-eastern South Australia and the south-east of the Northern Territory, but testimony from Aboriginal peoples indicates it also extended further west into the Great Sandy and Gibson Deserts of Western Australia. Being reported as common when last observed by Finlayson in the 1930s, its decline and extinction appears to have occurred entirely unobserved by western eyes, but it is likely that they were a victim of the usual troubles - invasive species and changing fire regimes.

#we were robbed of feisty bilbies#australian wildlife#wildlife#mammals#marsupials#bilby#lesser bilby#extinct#recently extinct#extinct species#extinction#animal facts#mammalogy#natural history#infodumps#my stuff

128 notes

·

View notes