#the mit press

Text

Output. An Anthology of Computer-Generated Text, 1953–2023, Edited by Lillian-Yvonne Bertram and Nick Montfort, The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 2024

(via J. R. Carpenter)

#graphic design#typography#computer science#computer technology#computer art#computer generated text#book#cover#book cover#lillian yvonne bertram#nick montfort#the mit press#2020s

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

كيف تَنتفِع من أداة "وام إنتلجنت" بصفتك كاتب محتوى؟

ما هذه المجموعة من المختارات تسألني؟ إنّها عددٌ من أعداد نشرة “صيد الشابكة” اِعرف أكثر عن النشرة هنا: ما هي نشرة “صيد الشابكة” ما مصادرها، وما غرضها؛ وما معنى الشابكة أصلًا؟! 🎣🌐

🎣🌐 صيد الشابكة العدد #45

صباح تعلّم كتابة المحتوى 👋🏼

🎣🌐 صيد الشابكة العدد #45🖊️🏃♂️ تَعلَّم من هاروكي موراكامي تَقبُّل أعمالك الإبداعية✨ كُن نزيهًا وتحلَّ بالشفافية عندما تحتاج وقتًا للراحة ولا تخف! سيتفهمك عملائك🤖🔍…

View On WordPress

#Adam Frank#AI agents#Alex Dobrenko#BIG THINK#Both Are True#David Szabo-Stuban#Dexa#Haruki Murukami#Henley & Partners#Jon Gillham#Marcelo Gleiser#mtchbk#The MIT Press#مجلة رسالة اليونسكو#مدونة مريم بازرعة#مدونة سالم حمده#مريم بازرعة#نشرة Alex Dobrenko#نشرة Both Are True#نشرة Indie Hackers#وكالة mtchbk#وكالة أنباء الإمارات#وام إنتلجنت#اندبندنت عربية#د. ماجد الخواجا#رسالة اليونسكو#سالم حمده#سالم حمده طب أسنان#شركة هانلي وشركائه

0 notes

Photo

“House in Arcosanti”, Arizona, U.S.A. _ 24.07.2022 _ SK

Zeitlian, Η. (ed) (1992). Semiotext(e) Architecture, Cambridge: The MIT Press.

https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/semiotexte-architecture

#House in Arcosanti#Arizona#U.S.A.#Semiotext(e) Architecture#The MIT Press#Anatopism#Collage#Architecture#Spyros Kaprinis#1992#2022

0 notes

Text

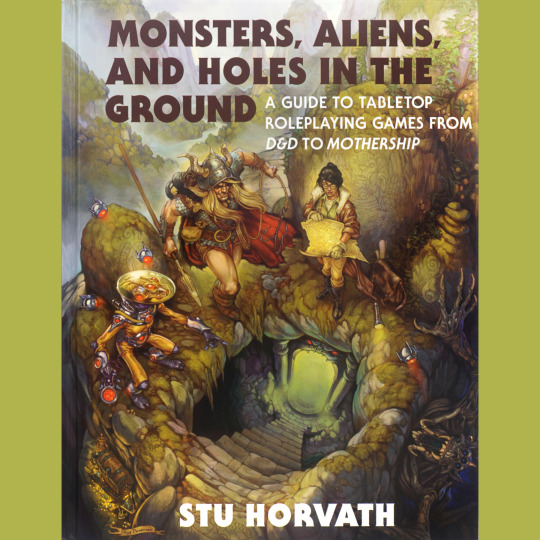

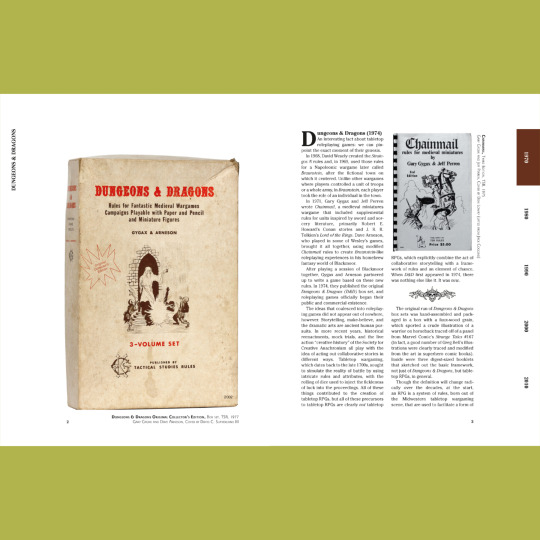

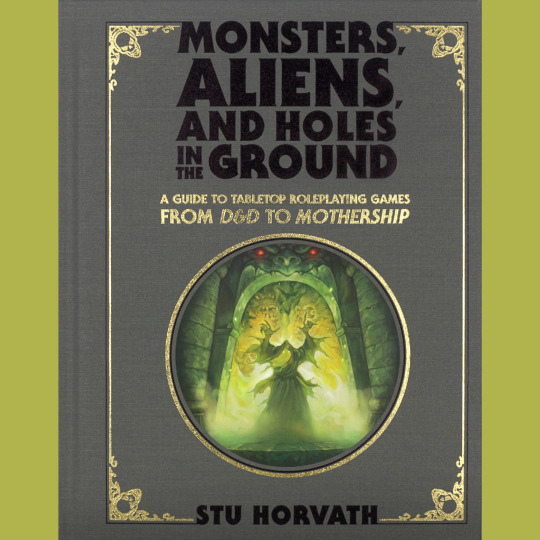

Hey! HEY! This is my book, Monsters, Aliens, and Holes in the Ground, coming to a bookstore near you on October 10, 2023 thanks to MIT Press. Pre-orders are live now pretty much everywhere, though I recommend using Bookshop.org, as I have been impressed at their packaging skillz. I have a real live copy of the book in my possession and I gotta say, it’s pretty neat.

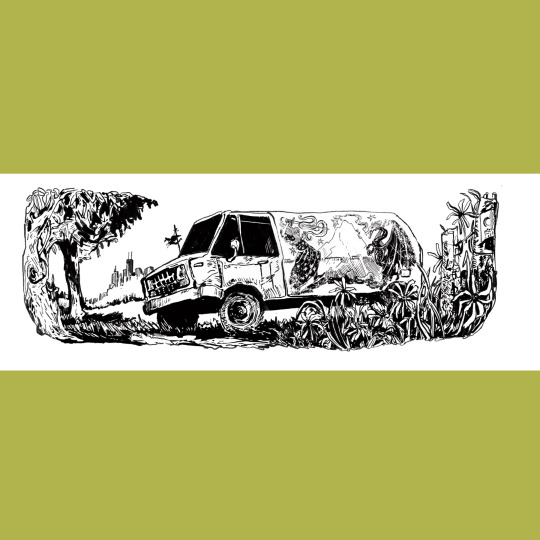

What is the book? It’s a look at the history and development of tabletop RPGs, one product at a time, arranged in chronological order across five decades. It’s sort of like this Instagram feed, actually, but way more polished, and, you know, on paper. I covered the classics, but this is also very much an exercise in expanding horizons — I hope there is at least one game featured for every reader that they never heard of. To that end, there are lots of lesser known games, weird games, silly games, even a couple board games. All pulled from my collection, all illustrated with something like 350 photographs.

There’s original art, too. Kyle Patterson did the amazing cover, somehow transforming my deeply silly post-it sketch (last slide) into a canny encapsulation of the RPG experience. He did a two-page spread introducing each decade, and effortlessly capturing its essence. He also did a handful of gorgeous spot illustrations. All of Kyle’s art makes me low-key angry. How dare he be so talented? I’ll share more of it, and some sketches, later on. You’ll be annoyed by his talent, too, I guarantee.

We (that’s myself and Derek Kinsman, who did the layout) also filled some empty spots with rights-free art from Amanda Lee Franck, evlynmoreau and natetreme, which is pretty rad - Amanda did the wizard van in the next to last slide - and also some Giovanni Battista Piranesi, cuz that dude had aesthetic for days.

And there you go, a first taste of 450-something pages of full-color RPG goodness. Go snag a copy now, yea? (Worth noting, this is the Standard edition. I’ll show you the Deluxe edition tomorrow.)

#rpg#d&d#dungeons & dragons#tabletop rpg#roleplaying game#ttrpg#MIT Press#Monsters Aliens and Holes in the Ground

607 notes

·

View notes

Text

Moral Hazard

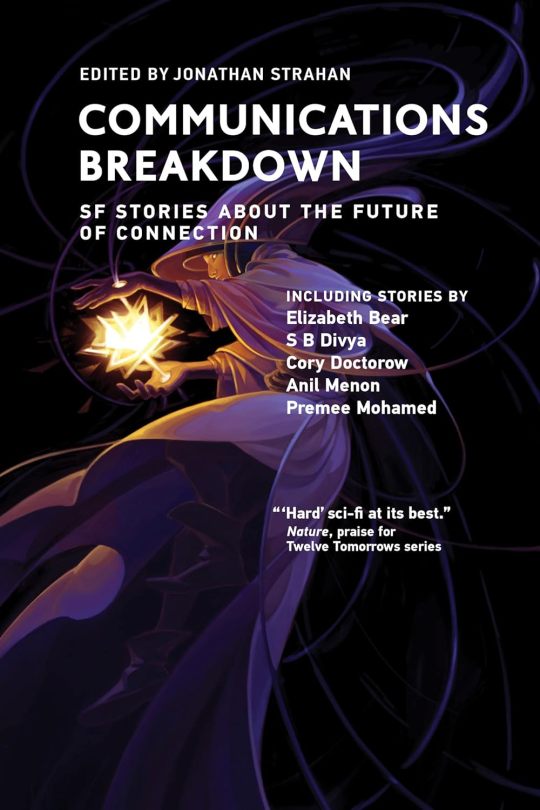

Today on my podcast, I read my short story "Moral Hazard," a madcap tale of fintech, inequality, finance bros, Wyoming, homelessness and bailouts. It's from "Communications Breakdown," a new anthology from MIT Press, edited by Jonathan Strahan, with stories from Elizabeth Bear, S.B. Divya, Chris Gilliard, Lavanya Lakshminarayan, Ken Macleod, Tim Maughan, Ian McDonald, Anil Menon, Premee Mohamed, and Shiv Ramdas.

Episode:

https://craphound.com/stories/2023/11/12/moral-hazard-from-communications-breakdown/

MP3:

https://archive.org/download/Cory_Doctorow_Podcast_455/Cory_Doctorow_Podcast_455_-_Moral_Hazard.mp3

Anthology:

https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262546461/communications-breakdown/

I know exactly where I was the day I decided to give every homeless person in America their own LLC. I was in the southeast corner of the sprawling homeless camp that had once been Seattle’s Discovery Park on a rare, dry February afternoon. The sun was weak but so welcome. After weeks of sheltering in our tents and squelching through the mud and getting drenched waiting for the portas, we were finally able to break out the folding chairs and enjoy each other’s company. Mike the Bike had coffee. He always did. Mike knew more ways to make coffee than any fancy barista. He had a master’s in chemical engineering and a bachelor’s in mechanical engineering and when he was high he spent every second of the buzz thinking of new ways to combine heat and water and solids to produce a perfect brew. I brought trail mix, which I mixed up myself with food-bank supplies and spices I bought from the bulk place for pennies. My secret is cardamom and a little chili powder. I learned that from my Mom. “Trish,” Mike the Bike said, “I wish I was a corporation.”

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Muriel Cooper - MIT Press

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

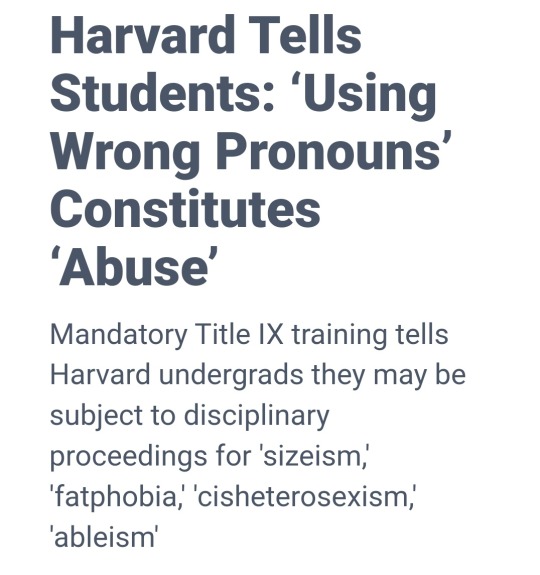

"Safety first." That’s the approach taken by university administrators these days.

On campuses across the country, "safety first" has been the rationale for silencing speech and firing professors. This practice has birthed a whole new moral framework, one that treats microaggressions as acts of violence.

"It's your job to create a place of comfort and home for the students."

But when it comes to threats and calls for genocide against the Jews...

"One solution! Intifada revolution!"

... it's a different story. Not safety first, but anything goes.

Just look at the facts. Last year, Harvard told students in a mandatory training session that using the wrong pronouns for a person constitutes abuse. "Sizeism and fatphobia," according to the session, are also attitudes that "contribute to an environment that perpetuates violence."

But when Harvard's president was asked by members of Congress this week in a hearing on campus antisemitism, if calling for the genocide of Jews constitutes bullying and harassment, here's what she said:

"It can be, depending on the context."

In 2018, the University of Pennsylvania barred law professor Amy Wax from teaching freshman after she said black students "rarely" finish in the top of their graduating class. Penn has since been trying to sanction Wax for statements the law school says violate its antidiscrimination policies.

But when Penn's president was asked if calls for genocide violate college rules, here's how she answered:

"If the speech turns into conduct, it can be harassment, yes."

"I am asking specifically calling for the genocide of Jews. Does that constitute bullying or harassment?"

"If it is directed and severe or pervasive, it is harassment."

"So the answer is yes."

"It is a context-dependent decision."

And when she was asked this:

"So is your testimony that you will not answer yes?"

This is what she said:

"If the speech becomes conduct, it can be harassment, yes."

"Conduct meaning committing the act of genocide? The speech is not harassment? This is unacceptable, Ms. Magill. I'm going to give you one more opportunity for the world to see your answer. Does calling for the genocide of Jews violate Penn's code of conduct when it comes to bullying and harassment? Yes or no?"

"It can be harassment."

In 2021, MIT canceled a major lecture about climate change by scientist Dorian Abbott because a group of graduate students disagreed with his belief that hiring should be based on a person's merit, rather than their identity. If MIT won’t tolerate unacceptable views, surely the college president would shut down chants of "Long live the intifada" on her campus...

"Long live the intifada!"

... right?

"At MIT, does calling for the genocide of Jews violate MIT‘s code of conduct or rules regarding bullying and harassment? Yes or no?"

"If targeted at individuals, not making public statements --"

"Yes or no? Calling for the genocide of Jews does not constitute bullying harassment?"

"I have not heard calling for the genocide for Jews on our campus."

"But you’ve heard chants for intifada?"

"I’ve heard chants, which can be antisemitic depending on the context when calling for the elimination of the Jewish people.

"So those would not be, according to the MIT's code of conduct or rules."

"That would be investigated as harassment, if pervasive and severe."

But antisemitic speech on campus has already escalated into physical violence.

Students at these campuses have been assaulted, targeted and harassed.

"Safety first." But when it comes to the Jews, it all depends on the "context."

==

It would be one thing if these universities had consistently refused to censor free speech, and told the students, "no, you have to accept that people can and will say things you don't like."

But they haven't. They've done the opposite. Claudine Gay, the president of Harvard, presided over the worst score any university has ever received on FIRE's College Free Speech Rankings: 0 out of 100. Actually, they scored lower than 0, but FIRE had to round it up.

https://www.thefire.org/news/harvard-gets-worst-score-ever-fires-college-free-speech-rankings

In 2020, Harvard ranked 46 out of 55 schools. In 2021, it ranked 130 out of 154 schools. Last year, it ranked 170 out of 203 schools. And this year, Harvard completed its downward spiral in dramatic fashion, coming in dead last with the worst score ever: 0.00 out of a possible 100.00. This earns it the notorious distinction of being the only school ranked this year with an “Abysmal” speech climate.

What’s more, granting Harvard a score of 0.00 is generous. Its actual score is -10.69, more than six standard deviations below the average and more than two standard deviations below the second-to-last school in the rankings, its Ivy League counterpart, the University of Pennsylvania. (Penn obtained an overall score of 11.13.)

These universities have done nothing but suppress speech, but suddenly they're free speech absolutists when it comes to calling for the extermination of all Jews?

This makes much more sense if you re-read the section on Dorian Abbott and take a moment to glance at the panel for a moment: they're all intersectional feminists put into top university positions as diversity hires for identarian reasons.

FIRE maintains a Disinvitation Database.

Harvard:

University of Pennsylvania

MIT

I keep seeing people making excuses that "intifada" means anything from just demonstrations to more aggressive armed action, so calling for "intifada" is not necessarily a call to genocide.

The problem here is the same as "faith." There is, by definition, no boundary on "faith," so as soon as you endorse "faith" as a way to know the world, you forfeit the right to judge what others do based on "faith." If "intifada" is so broadly defined, you don't get to say, "well, to me it means demonstrations." It doesn't matter how you define it, privileged Western college student, it only matters what the sickest, most depraved, most psychopathic Palestinian does in the name of the far-right Islamic religion, ideology and movement you've just promoted and endorsed. There's no distinction between your "intifada" and theirs.

By calling for "intifada," you endorse anything and everything done under that banner. (Besides which, we all know by now that "pro-Palestine" activists are really pro-Hamas, due to their abject refusal to condemn the Islamic jihadi terrorists.)

Now remember that Hamas are jihadi Islamic supremacists, and Palestinian civilians were also involved in the attacks, including dragging dead Israelis through the streets and beating captives in the backs of trucks. So, when they seek "intifada," are they more likely to veer more towards "demonstrations" or are they more likely to go more in the direction of a genocidal atrocity?

"You should attack every Jew possible in all the world and kill them."

-- Fathi Hamad, political leader of Hamas.

"Israel will exist and will continue to exist until Islam will obliterate it, just as it obliterated others before it."

-- Hamas Covenant, 1988

https://quranx.com/Hadith/Bukhari/USC-MSA/Volume-1/Book-8/Hadith-387

Narrated Anas bin Malik:

Allah's Messenger (ﷺ) said, "I have been ordered to fight the people till they say: 'None has the right to be worshipped but Allah.' And if they say so, pray like our prayers, face our Qibla and slaughter as we slaughter, then their blood and property will be sacred to us and we will not interfere with them except legally and their reckoning will be with Allah."

🤔

#Maya Sulkin#Bari Weiss#safetyism#antisemitism#The Free Press#Mein Context#intifada#genocide#free speech#freedom of speech#academic corruption#censorship#pronoun culture#pronouns#Harvard University#massachusetts institute of technology#MIT#University of Pennsylvania#UPenn#religion is a mental illness

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

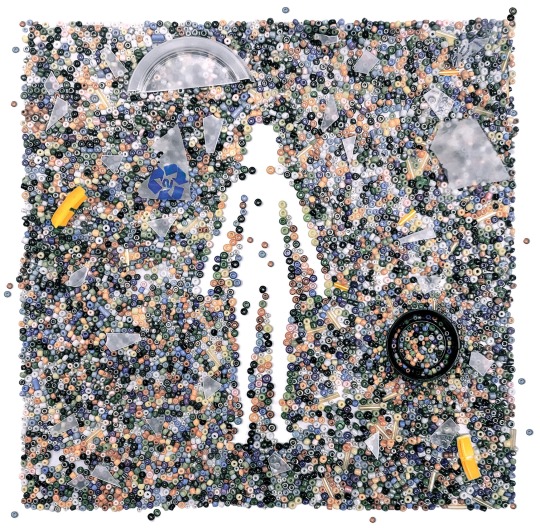

How Plastics Are Poisoning Us

They both release and attract toxic chemicals, and appear everywhere from human placentas to chasms thirty-six thousand feet beneath the sea. Will we ever be rid of them?

— By Elizabeth Kolbert | June 26, 2023

Annual production of plastic exceeds eight hundred billion pounds; much of it ends up as microplastics, spreading across the ocean. Illustration by Daniel Liévano

In 1863, when much of the United States was anguishing over the Civil War, an entrepreneur named Michael Phelan was fretting about billiard balls. At the time, the balls were made of ivory, preferably obtained from elephants from Ceylon—now Sri Lanka—whose tusks were thought to possess just the right density. Phelan, who owned a billiard hall and co-owned a billiard-table-manufacturing business, also wrote books about billiards and was a champion billiards player. Owing in good part to his efforts, the game had grown so popular that tusks from Ceylon—and, indeed, elephants more generally—were becoming scarce. He and a partner offered a ten-thousand-dollar reward to anyone who could come up with an ivory substitute.

A young printer from Albany, John Wesley Hyatt, learned about the offer and set to tinkering. In 1865, he patented a ball with a wooden core encased in ivory dust and shellac. Players were unimpressed. Next, Hyatt experimented with nitrocellulose, a material made by combining cotton or wood pulp with a mixture of nitric and sulfuric acids. He found that a certain type of nitrocellulose, when heated with camphor, yielded a shiny, tough material that could be molded into practically any shape. Hyatt’s brother and business partner dubbed the substance “celluloid.” The resulting balls were more popular with players, although, as Hyatt conceded, they, too, had their drawbacks. Nitrocellulose, also known as guncotton, is highly flammable. Two celluloid balls knocking together with sufficient force could set off a small explosion. A saloon owner in Colorado reported to Hyatt that, when this happened, “instantly every man in the room pulled a gun.”

It’s not clear that the Hyatt brothers ever collected from Phelan, but the invention proved to be its own reward. From celluloid billiard balls, the pair branched out into celluloid dentures, combs, brush handles, piano keys, and knickknacks. They touted the new material as a substitute not just for ivory but also for tortoiseshell and jewelry-grade coral. These, too, were running out, owing to slaughter and plunder. Celluloid, one of the Hyatts’ advertising pamphlets promised, would “give the elephant, the tortoise, and the coral insect a respite in their native haunts.”

Hyatt’s invention, often described as the world’s first commercially produced plastic, was followed a few decades later by Bakelite. Bakelite was followed by polyvinyl chloride, which was, in turn, followed by polyethylene, low-density polyethylene, polyester, polypropylene, Styrofoam, Plexiglas, Mylar, Teflon, polyethylene terephthalate (familiarly known as pet)—the list goes on and on. And on. Annual global production of plastic currently runs to more than eight hundred billion pounds. What was a problem of scarcity is now a problem of superabundance.

In the form of empty water bottles, used shopping bags, and tattered snack packages, plastic waste turns up pretty much everywhere today. It has been found at the bottom of the Mariana Trench, thirty-six thousand feet below sea level. It litters the beaches of Svalbard and the shores of the Cocos (Keeling) Islands, in the Indian Ocean, most of which are uninhabited. The Great Pacific Garbage Patch, a collection of floating debris that stretches across six hundred thousand square miles between California and Hawaii, is thought to contain some 1.8 trillion plastic shards. Among the many creatures being done in by all this junk are corals, tortoises, and elephants—in particular, the elephants of Sri Lanka. In recent years, twenty of them have died after ingesting plastic at a landfill near the village of Pallakkadu.

How worried should we be about what’s become known as “the plastic pollution crisis”? And what can be done about it? These questions lie at the heart of several recent books that take up what one author calls “the plastic trap.”

“Without plastic we’d have no modern medicine or gadgets or wire insulation to keep our homes from burning down,” that author, Matt Simon, writes in “A Poison Like No Other: How Microplastics Corrupted Our Planet and Our Bodies.” “But with plastic we’ve contaminated every corner of Earth.”

Simon, a science journalist at Wired, is especially concerned about plastic’s tendency to devolve into microplastics. (Microplastics are usually defined as bits smaller than five millimetres across.) This process is taking place all the time, in many different ways. Plastic bags drift into the ocean, where, after being tossed around by the waves and bombarded with UV radiation, they fall apart. Tires today contain a wide variety of plastics; as they roll along, they abrade, sending clouds of particles spinning into the air. Clothes made with plastics, which now comprise most items for sale, are constantly shedding fibres, much the way dogs shed hairs. A study published a few years ago in the journal Nature Food found that preparing infant formula in a plastic bottle is a good way to degrade the bottle, so what babies end up drinking is a sort of plastic soup. In fact, it is now clear that children are feeding on microplastics even before they can eat. In 2021, researchers from Italy announced that they had found microplastics in human placentas. A few months later, researchers from Germany and Austria announced that they’d found microplastics in meconium—the technical term for an infant’s first poop.

The hazards of ingesting large pieces of plastic are pretty straightforward; they include choking and perforation of the intestinal tract. Animals that fill their guts with plastics eventually starve to death. The risks posed by microplastics are subtler, but not, Simon argues, any less serious. Plastics are made from by-products of oil and gas refining; many of the chemicals involved, such as benzene and vinyl chloride, are carcinogens. In addition to their main ingredients, plastics may contain any number of additives. Many of these—for example, polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFASs, which confer water resistance—are also suspected carcinogens. Many of the others have never been adequately tested.

As plastics fall apart, the chemicals that went into their manufacture can leak out. These can then combine to form new compounds, which may prove less dangerous than the originals—or more so. A couple of years ago, a team of American scientists subjected disposable shopping bags to several days of simulated sunlight, in order to mimic the conditions that they’d encounter flying or floating loose. The researchers found that a single bag from CVS leached more than thirteen thousand compounds; a bag from Walmart leached more than fifteen thousand. “It is becoming increasingly clear that plastics are not inert in the environment,” the team wrote. Steve Allen, a researcher at Canada’s Ocean Frontier Institute who specializes in microplastics, tells Simon, “If you’ve got an IQ above room temperature, you have to understand that this is not a good material to have in the environment.”

Microplastics, meanwhile, don’t just leach nasty chemicals; they attract them. “Persistent bioaccumulative and toxic substances,” or PBTs, are a hodgepodge of harmful compounds, including DDT and PCBs. Like microplastics, which are often referred to in the scientific literature as MPs, PBTs are everywhere these days. When PBTs encounter MPs, they preferentially adhere to them. “In effect, plastics are like magnets for PBTs” is how the Environmental Protection Agency has put it. Consuming microplastics is thus a good way to swallow old poisons.

Then, there’s the threat posed by the particles themselves. Microplastics—and in particular, it seems, microfibres—can get pulled deep into the lungs. People who work in the synthetic-textile industry, it has long been known, suffer from high rates of lung disease. Are we breathing in enough microfibres that we are all, in effect, becoming synthetic-textile workers? No one can say for sure, but, as Fay Couceiro, a researcher at England’s University of Portsmouth, observes to Simon, “We desperately need to find out.”

Whatever you had for dinner last night, the meal almost certainly left behind plastic in need of disposal. Before tossing your empty sour-cream tub or mostly empty ketchup bottle, you may have searched it for a number, and if you found one, inside a cheerful little triangle, you washed it out and set it aside to be recycled. You might also have imagined that with this effort you were doing your part to stem the global plastic-pollution tide.

The British journalist Oliver Franklin-Wallis used to be a believer. He religiously rinsed his plastics before depositing them in one of the five color-coded rubbish bins that he and his wife kept at their home in Royston, north of London. Then Franklin-Wallis decided to find out what was actually happening to his garbage. Disenchantment followed.

“If a product is seen as recycled, or recyclable, it makes us feel better about buying it,” he writes in “Wasteland: The Secret World of Waste and the Urgent Search for a Cleaner Future.” But all those little numbers inside the triangles “mostly serve to trick consumers.”

Franklin-Wallis became interested in the fate of his detritus just as the old order of Britain’s rubbish was collapsing. Up until 2017, most of the plastic waste collected in Europe and in the United States was shipped to China, as was most of the mixed paper. Then Beijing imposed a new policy, known as National Sword, that prohibited imports of yang laji, or “foreign garbage.” The move left waste haulers from California to Catalonia with millions of mildewy containers they couldn’t get rid of. “plastics pile up as china refuses to take the west’s recycling,” a January, 2018, headline in the Times read. “It’s tough times,” Simon Ellin, the chief executive of Britain’s Recycling Association, told the paper.

Trash, though, finds a way. Not long after China stopped taking in foreign garbage, waste entrepreneurs in other nations—Malaysia, Indonesia, Vietnam, Sri Lanka—started to accept it. Mom-and-pop plastic-recycling businesses sprang up in places where they were regulated laxly, if at all. Franklin-Wallis visited one such informal recycling plant, in New Delhi; the owner allowed him inside on the condition that he not reveal exactly how the business operates or where it is situated. He found workers in a fiendishly hot room feeding junk into a shredder. Workers in another, equally hot room fed the shreds into an extruder, which pumped out little gray pellets known as nurdles. The ventilation system consisted of an open window. “The thick fug of plastic fumes in the air left me dazed,” Franklin-Wallis writes.

Nurdles, which are key to manufacturing plastic products, are small enough to qualify as microplastics. (It’s been estimated that ten trillion nurdles a year leak into the oceans, most from shipping containers that tip overboard.) Usually, nurdles are composed of “virgin” polymers, but, as the New Delhi plant demonstrates, it is also possible to produce them from used plastic. The problem with the process, and with plastic recycling more generally, is that a polymer degrades each time it’s heated. Thus, even under ideal circumstances, plastic can be reused only a couple of times, and in the waste-management business very little is ideal. Franklin-Wallis toured a high-end recycling plant in northern England that handles pet, the material that most water and soda bottles are made from. He learned that nearly half the bales of pet that arrive at the plant can’t be reprocessed because they’re too contaminated, either by other kinds of plastic or by random crap. “Yield is a problem for us,” the plant’s commercial director concedes.

Franklin-Wallis comes to see plastic recycling as so much (potentially toxic) smoke and mirrors. Over the years, he writes, “a kind of playbook” has emerged. Under public pressure, a company like Coca-Cola or Nestlé pledges to insure that the packaging for its products gets recycled. When the pressure eases, it quietly abandons its pledge. Meanwhile, it lobbies against any kind of legislation that would restrict the sale of single-use plastics. Franklin-Wallis quotes Larry Thomas, the former president of the Society of the Plastics Industry, who once said, “If the public thinks recycling is working, then they are not going to be as concerned about the environment.”

Right around the time that Franklin-Wallis started tracking his trash, Eve O. Schaub decided to spend a year not producing any. Schaub, who has been described as a “stunt memoirist,” had previously spent a year avoiding sugar and forcing her family to do the same, an exercise she chronicled in a book titled “Year of No Sugar.” The year of no sugar was followed by “Year of No Clutter.” When she proposes a trash-free annum to her husband, he says he doubts it is possible. Her younger daughter begs her to wait until she goes away to college. Schaub plunges ahead anyway.

“As the beginning of the new year loomed, I was feeling pretty good about our chances,” she recalls in “Year of No Garbage.” “I mean, really. How hard could it be?”

What Schaub means by “no garbage” is not exactly no garbage. Under her scheme, refuse that can be composted or recycled is allowed, so her family can keep tossing out old cans and empty wine bottles along with food scraps. What turns out to be hard—really, really hard—is dealing with plastic.

At first, Schaub divides plastic waste into two varieties. There’s the kind with the little numbers, which her trash hauler accepts as part of its “single stream” recycling program and so, by her definition, doesn’t count as trash. Then, there’s the kind with no numbers, which isn’t supposed to go in the recycling bin and therefore does count. Schaub finds that even when she purchases something in a numbered container—guacamole, say—there’s usually a thin sheet of plastic under the lid that’s numberless. A lot of her time goes into rinsing off these sheets and other stray plastic bits and trying to figure out what to do with them. She is excited to find a company called TerraCycle, which promises—for a price—to “recycle the unrecyclable.” For a hundred and thirty-four dollars, she purchases a box that can be returned to TerraCycle filled with plastic packaging, and for an additional forty-two dollars she buys another box that can be filled with “oral care waste,” such as used toothpaste tubes. “I sent my TerraCycle Plastic Packaging box as densely packed with plastic as any box could be,” she writes.

Eventually, though, like Franklin-Wallis, Schaub comes to see that she’s been living a lie. Midway through her experiment, she signs up for an online course called Beyond Plastic Pollution, offered by Judith Enck, a former regional administrator for the E.P.A. Only containers labelled No. 1 (pet) and No. 2 (high-density polyethylene) get melted down with any regularity, Schaub learns, and to refashion the resulting nurdles into anything useful usually requires the addition of lots of new material. “No matter what your garbage service provider is telling you, numbers 3, 4, 6 and 7 are not getting recycled,” Schaub writes. (The italics are hers.) “Number 5 is a veeeery dubious maybe.”

TerraCycle, too, proves a disappointment. It gets sued for deceptive labelling and settles out of court. A documentary-film crew finds that dozens of bales of waste sent to the company for recycling have instead been shipped off to be burned at a cement kiln in Bulgaria. (According to the company’s founder, this is the result of an unfortunate mistake.)

“I had wanted so badly to believe that TerraCycle and Santa Claus and the Easter bunny were real, that I had been willing to overlook the fact that Santa’s handwriting looks suspiciously like Mom’s,” Schaub writes. Toward the end of the year, she concludes that pretty much all plastic waste—numbered, unnumbered, or shipped off in boxes—falls under her definition of garbage. She also concludes that, “in this day, age and culture,” such waste is pretty much impossible to avoid.

A few months ago, the E.P.A. issued a “draft national strategy to prevent plastic pollution.” Americans, the report noted, produce more plastic waste each year than the residents of any other country—almost five hundred pounds per person, nearly twice as much as the average European and sixteen times as much as the average Indian. The E.P.A. declared the “business-as-usual approach” to managing this waste to be “unsustainable.” At the top of its list of recommendations was “reduce the production and consumption” of single-use plastics.

Just about everyone who contemplates the “plastic pollution crisis” arrives at the same conclusion. Once a plastic bottle (or bag or takeout container) has been tossed, the odds of its ending up in landfill, on a faraway beach, or as tiny fragments drifting around in the ocean are high. The best way to alter these odds is not to create the bottle (or bag or container) in the first place.

“So long as we’re churning out single-use plastic . . . we’re trying to drain the tub without turning off the tap,” Simon writes. “We’ve got to cut it out.”

“We can’t rely on half-measures,” Schaub says. “We have to go to the source.” Her own local supermarket, in southern Vermont, stopped handing out plastic bags in late 2020, she notes. “Do you know what happened? Nothing. One day we were poisoning the environment with plastic bags in the name of ultra-convenience and the next? We weren’t.”

“We now know that we can’t start to reduce plastic pollution without a reduction of production,” Imari Walker-Franklin and Jenna Jambeck, both environmental engineers, observe in “Plastics,” forthcoming from M.I.T. Press. “Upstream and systemic change is needed.”

Of course, it’s a lot easier to talk about “turning off the tap” and changing the system than it is to actually do so. First, there are the political obstacles. For all intents and purposes, the plastics industry is a subsidiary of the fossil-fuel industry. ExxonMobil, for instance, is the world’s fourth-largest oil company and also its largest producer of virgin polymers. The connection means that any effort to reduce plastic consumption is bound to be resisted, either openly or surreptitiously, not just by companies such as Coca-Cola and Nestlé but also by corporations like Exxon and Shell. In March, 2022, diplomats from a hundred and seventy-five nations agreed to try to fashion a global treaty to “end plastic pollution.” At the first negotiating session, held later that year in Uruguay, the self-described High Ambition Coalition, which includes the members of the European Union as well as Ghana and Switzerland, insisted that the treaty include mandatory measures that apply to all countries. This idea was opposed by major oil-producing nations, including the U.S., which has called for a “country-driven” approach. According to the environmental group Greenpeace, lobbyists for the “major fossil fuel companies were out in force” at the session.

There are also practical hurdles. Precisely because plastic is now ubiquitous, it’s difficult to imagine how to replace all of it, or even much of it. Even in cases where substitutes are available, it’s not always clear that they’re preferable. Franklin-Wallis cites a 2018 study by the Danish Environmental Protection Agency which analyzed how different kinds of shopping bags compare in terms of life-cycle impacts. The study found that, to have a lower environmental impact than a plastic bag, a paper bag would have to be used forty-three times and a cotton tote would have to be used an astonishing seventy-one hundred times. “How many of those bags will last that long?” Franklin-Wallis asks. Walker-Franklin and Jambeck also note that exchanging plastic for other materials may involve “tradeoffs,” including “energy and water use and carbon emissions.” When Schaub’s supermarket stopped handing out plastic shopping bags, it may have reduced one problem only to exacerbate others—deforestation, say, or pesticide use.

“In the grand scheme of human existence, it wasn’t that long ago that we got along just fine without plastic,” Simon points out. This is true. It also wasn’t all that long ago that we got along just fine without Coca-Cola or packaged guacamole or six-ounce bottles of water or takeout everything. To make a significant dent in plastic waste—and certainly to “end plastic pollution”—will probably require not just substitution but elimination. If much of contemporary life is wrapped up in plastic, and the result of this is that we are poisoning our kids, ourselves, and our ecosystems, then contemporary life may need to be rethought. The question is what matters to us, and whether we’re willing to ask ourselves that question. ♦

— Published in the print edition of the July 3, 2023, The New Yorker Issue, with the headline “A Trillion Little Pieces.”

#Plastic Poisoning#Toxic Chemicals#On Earth and Under Seas#Microplastics#Plastic Pollution#PFASs#PBTs#MPs DDT & PCBs#E.P.A.#MIT Press#Coca Cola | Nestlé | Exxon | Shell#Greenpeace

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

auslöser _filmverband sachsen 03 2009 (press archive: shared folder)

#press archive#auslöser#filmverband sachsen#03#2009#wuhan#sächsische filmemacher zu besuch in china#whisky mit wodka#andreas dresen#hinterhof-blues#cinemabstruso#im nächsten leben#marco mittelstaedt#alle anderen#maren ade#the countess#julie delpy#inglourious basterds#brad pitt#quentin tarantino

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

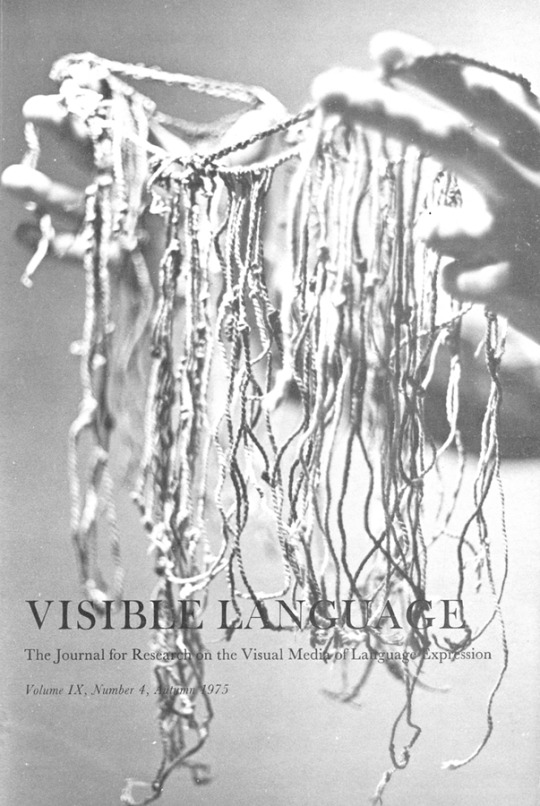

«Visible Language» – The Journal for Research on the Visual Media of Language Expression, Volume IX, Number 4, Autumn 1975, The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA. Cover: An lncan quipu in the collection of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA (full issue pdf here)

#graphic design#visual communication research#visual writing#textile#journal#magazine#cover#magazine cover#visible language#the mit press#peabody museum of archaeology and ethnology#1970s

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

The MIT Press Podcast: How are Sports Teams Using Data Science?

"In this episode, the journal's Features Editor Liberty Vittert and Editor in Chief Xiao-Li Meng dig into the data behind sports with two experts: Brian Macdonald, sports analytics at Yale (formerly Carnegie Mellon University) and Kirk Goldsberry, NBA analyst at ESPN and author of Sprawlball: A Visual Tour of the New era of the NBA."

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ich muss jetzt ernsthaft mit dieser Folge (die ich mit 2 von 5 Sternen bewertet habe - 1 Stern für Moritz, weil er gut aussah, 1 Stern für das Ende mit der Musik) in die Pause gehen und bekomme ungefähr sechs Monate keine neue Folge zu sehen? Heißt, die Ereignisse aus dieser Folge bleiben so lange der Status Quo? Als wären die Ereignisse nicht ätzend genug.

#soko leipzig#k watches soko leipzig#ich werde die folge ignorieren und verdrängen#zumindest die szenen zwischen moritz und kim#was mich darauf bringt...#in der press release hieß es doch was von wegen jan und ina bekommen was davon mit?#davon hab ich wiederum nichts mitbekommen

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

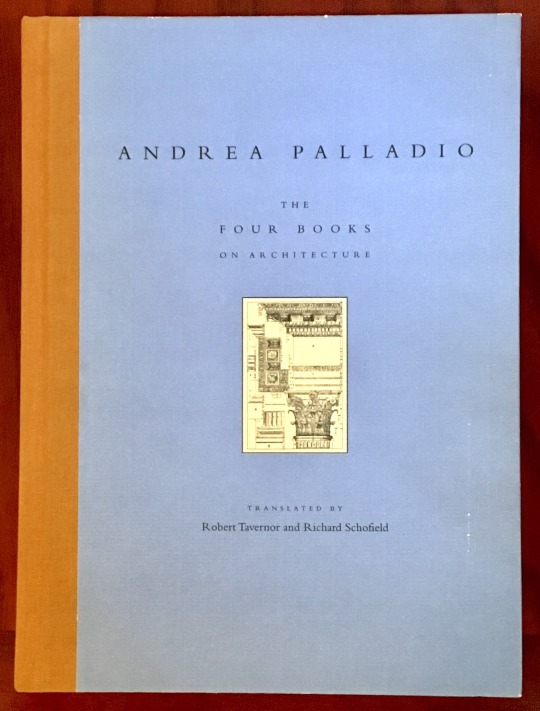

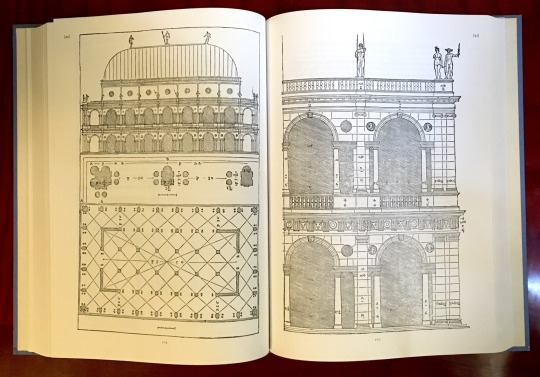

Book 408

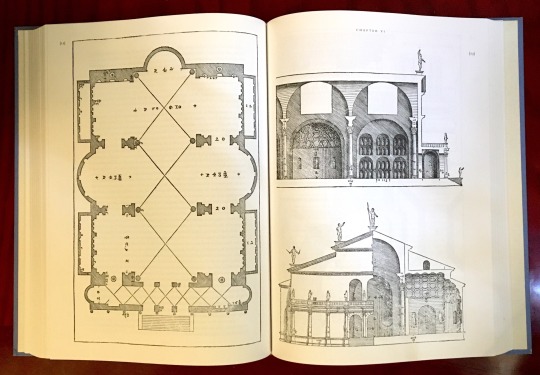

The Four Books on Architecture

Andrea Palladio / translated by Robert Tavernor and Richard Schofield

The MIT Press 1998

Renaissance architect Andrea Palladio (1508-1580) is one of the most influential figures in the field of architecture, and his Four Books on Architecture, first published in 1570, are still universally regarded as some of the most important books in the literature of the field. With a new translation by Robert Tavernor and Richard Schofield, the first English translation since 1738, this MIT edition is both notable and lovely. Containing new reproductions of the original woodcuts, Palladio’s architectural diagrams and plans are models of balance and composition that exemplify the mathematical and harmonic beauty of proportion.

#bookshelf#illustrated book#library#personal library#personal collection#books#book lover#bibliophile#booklr#andrea palladio#the four books on architecture#mit press#Robert Tavernor#Richard Schofield#architecture

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

OK, so, as if having a massive book on RPGs coming out in October wasn’t exciting enough, I actually have two massive books on RPGs coming out in October? Sort of. Same tasty words and pictures (with one exception, I’ll get to that in a minute), but totally different candy coating. This is the DELUXE edition of Monsters, Aliens, and Holes in the Ground, published by MIT Press and due on shelves October 10.

As you can see, we have a clothbound book and slipcase, stamped with both gold and black foil. There is a dramatic increase in the number of skulls on display. We also have an entirely different piece of Kyle Patterson’s art set in as a medallion on the cover there. There is a sewn-in ribbon bookmark (natch), the pages are gilt and the inside of the slipcase is a lustrous gold. As I said, the interior is essentially the same, but with one key difference: this one has custom end pages in the front and back — those shelfies. That was a last minute addition in the production and I legit forgot about them until I opened the book for the first time and they look so dang cool. It’s the little things.

Also, because there is nothing worse than having to forgo rad regular art for the special edition, they included an 8.5x11-inch card stock print (sans text) of Kyle’s painting for the standard edition inside the slipcase.

The deluxe is also up for pre-order everywhere. I can not stress how much I recommend pre-ordering this version via Bookshop if you want rest assured it will arrive in good shape. I also recommend pre-ordering the deluxe if you want to be sure to get it in October, as they were printed in a smaller quantity and I know at least my Patrons are snagging them fast.

#rpg#d&d#dungeons & dragons#tabletop rpg#roleplaying game#ttrpg#Monsters Aliens and Holes in the Ground#MIT Press

130 notes

·

View notes

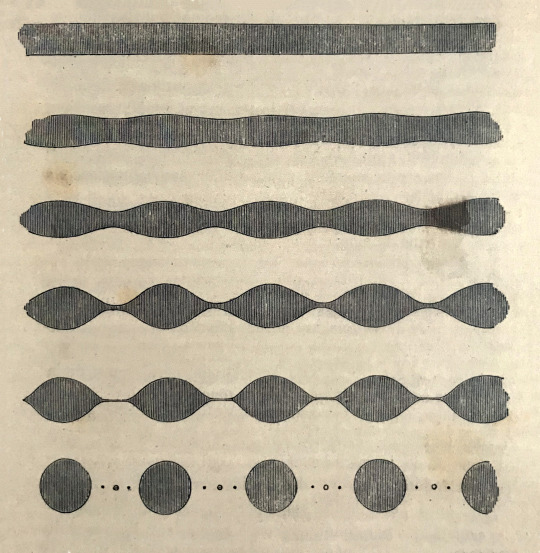

Photo

When milk - is not just milk.

Three from Milk and Melancholy by Kenneth Hayes, Prefix Institute of Contemporary Art - MIT Press, 2008

Top: Joseph Plateau, Statique experimentale et theorique des liquids soumis auz seules forces moleculaires (Experimental and theoretical study of liquids subjected only to molecular forces), 1873 - Ghent University Library

Centre: Sigmar Polke, Tisch Mit Umgekkippter Kanne (Table with Overturned Jug), 1970 - courtesy of the artist

Bottom: Jeff Wall, Milk, 1984 - courtesy of the artist

https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/milk-and-melancholy

#jeff wall#joseph plateau#sigmar polke#prefix photo#mit press#milk#melancolía#photography#kenneth hayes

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Currently Reading

Mark Wittman

ALTERED STATES OF CONSCIOUSNESS

Experiences Out of Time and Self

Translated from the German by Philippa Hurd

#reading#Mark Wittman#Philippa Hurd#2023#MIT Press#consciousness#entheogens#altered states#human evolution

0 notes