#yugoslavia history

Text

Monument dedicated to Serb and Albanian partisans, Mitrovica, Kosovo, 1973, designed by Bogdan Bogdanović. Photo by Ricardo Conte.

(Design Milk)

#kosovo#sculpture#architecture#military history#wwii#ww2#world war ii#world war 2#design#monument#serbia#albania#yugoslavia

239 notes

·

View notes

Text

I did this colourization of what I assume is a mother and her 2 daughters. The woman in the centre is wearing zar (robe) and peča (black face veil). The girls are wearing bošča (shawls). The picture was taken in Bosnia sometime between 1918 and 1950.

The original b+w is from: https://gams.uni-graz.at/o:vase.2577

#bosnia#bosnia and herzegovina#bosna i hercegovina#muslim#islam#muslim women#hijab#niqab#history#colorized#colorization#yugoslavia#jugoslavija

166 notes

·

View notes

Text

Serbian peasant who came to collect Red Cross aid, Pirot, August 1919.

107 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arsenopyrite and calcite

Natural History Museum of Denmark, Mineral Hall

#arsenopyrite#calcite#geology#minerals#mineralology#mineral hall#yugoslavia#serbia#museum#museums#danish museums#denmark#copenhagen#natural history#natural history museum#natural history museum of denmark#danish natural history museum

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

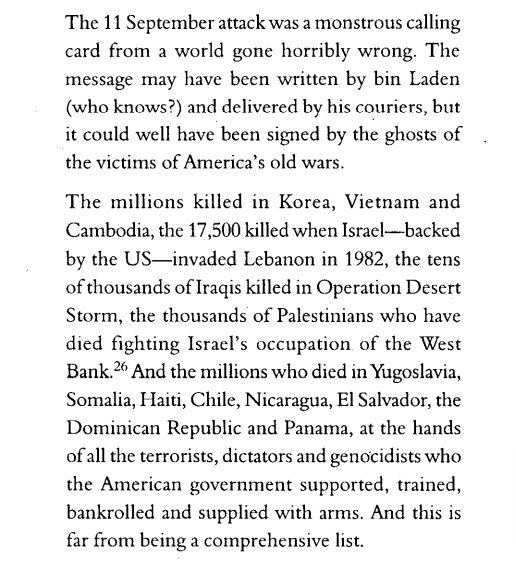

Arundhati Roy - The Algebra of Infinite Justice

#arundhati roy#the algebra of infinite justice#quote#september 11#9 1 1#korean war#vietnam#vietnam war#palestine#israel#cambodia#colonialism#imperialism#american imperialism#war#yugoslavia#politics#history#essay#book quotes#female writers#afghanistan#iraq#iraq war#trash

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sokovia falls in spring.

Much of it is blurry now, forced into oblivion, but he remembers that part with vicious detail - the unassuming, forgettable prelude to hell; Lazarus Saturday, the intermittent tinkling of bells down their cul-de-sac and the heavy wet air while he sat out on the wide expanse of the balcony, sipping on his lukewarm coffee and sneaking a rare indulgent cigarette while the house was empty. It'd done little to ward against the chill of the morning, the kind of cold that broke him out into consistent goosebumps and seeped down into his bones, seemingly misplaced in early April. The metal railing stuck to the warm skin of his forearms when he leaned over it to peer idly down at the street, to where snow had accumulated in front of the row of brand-new luxury apartment buildings; all alike in their appearance, all that same shiny glass and metal and blinding white that had become popular in the last fifteen years, fifteen years too late in regards to the rest of the world, and that would fall apart in about as many. All laid out like a poor man's idea of opulence and a stark contrast to the unkempt street.

He'd hated it initially - hates it still, really. The cheap sterility of it, this sign of the times made palpable infrastructure that was devouring what was left of a once beautiful neighborhood, clashing with the old, dilapidated villas and steadfastly grey communist architecture. But Sandra had said, it's a peaceful neighborhood. There's a good school nearby. Sandra had said, There's a life for us here, love, and it'll be a good change of pace. Look how beautiful the view is from up here. Sandra had said: just because you grew up in exile doesn't mean Miho should.

And she was right. So a pristine-white, new-century-cold castle on the hill it was. He could still fit his dream of a future in Sokovia into a different shape, he told himself; what mattered was what was inside, anyway.

He'd watched as a gaggle of children slipped and skittered their way downhill from the international school, kicking the stray willow wreaths that had slipped off the heads of previous passersby back and forth until they'd get stuck in the muddy slush, and found himself wishing again that he'd gone with his wife and son to visit her mother in Kralyev Pole. But he was scheduled to go back to Vienna in the morning - it was a familiar rhythm by now - and Sandra had just pressed a firm kiss to his cheek and said we'll see you back home at Easter in a purposeful, loving tone that almost got lost between the distracted flurry of packing and her distant eyes.

Looking down at the murky palette of the street below he'd wished, not for the first time, that it'd all felt a little more like home. That he wasn't itching to be back on that plane out of the country the second he landed, a feeling amped up to 11 the second his family had set foot outside the building.

But then again, Novi Grad had never been his home; not really, not in any way that mattered.

He'd been in a foul mood already when his father called, the glaring absence of sound from the open double doors behind him and the grey sky pressing down over his head like a steel trap setting his teeth on edge. He'd let the phone ring and ring for almost a full minute before guilt had finally, inevitably, won over.

Their conversation had been relatively brief, caught between perfunctory and utilitarian, much like all of their other phone conversations since he'd started splitting his time between Sokovia and work abroad. They talked about the unexpected snow, about what is to be done for the anniversary of his mother's death, about whether Mihailo would like a BMX sports bicycle for his birthday. He'd tried explaining that his son still didn't really know how to ride one well - that at eight, the five-speed he already had was perfectly fine, thank you, but it's a nice thought. His father had just scoffed.

"You were never athletic as a child either, you know. Never climbed trees with the other children. Always too afraid of falling, I suppose," he'd said mostly to himself, and then, "If the kid actually had someone around to teach him, maybe he'd be learning faster."

On a different day, he might've let it slide. On a different day, he wouldn't have let the sentimental old age in his father's voice feel like a personal affront. "Nobody ever taught me, and I learned just fine."

This wasn't necessarily true. For most of his young life, Zemo had been coached by a wide plethora of professionals: French, German, Latin, shooting, violin, tennis, horseback riding, mountaineering, art, diplomacy, you name it - he'd had a teacher for every single one of the skills his parents and his surroundings had deemed necessary for a young man of his stature, and eventually, with more or less effort, he'd excelled at all of them; but never alone. There'd been Katya, the au pair that practically raised him in his childhood, young herself and lost in a foreign country and still the warmest presence he'd had in his life. There'd been Oeznik, who'd governed him with a much stricter hand than his own parents, but who had guarded Zemo's life with his own nonetheless.

It's just that things like big-game hunting and history lessons took precedence over things like bike riding and soccer, which was just as well, really. He never liked being mundane.

At the Academy it was a different story altogether. Unnoticeability, the skill of being no more interesting than the person next to him, only came later, and at a cost.

"Just make sure your Germans let you out in time for Easter," the old man'd muttered, "if they even recognize that sort of thing."

He remembers that part clearly, too, that bitter emphasis: your Germans. Like Zemo'd picked the wrong thing to do with his abundant time and money, the wrong way to employ his very specialized skill set, the wrong side of the family to lean into; like his name and heritage were something he'd picked himself and not something that was hammered into him by way of memorization, that he was taught to take pride in and embody down to the last detail. Like this mild-mannered, West-oriented young man who spoke German and a handful of other languages softly but deftly, who subsumed all his wilder impulses and hid his smoking and all his other dirty habits from his family and from the world behind a courteous smile wasn't an inadvertent yet nonetheless direct creation of the man on the other end of the line. A prince and a baron, turned a lowly gastarbeiter.

"They're Austrian," Zemo'd said simply. "Look, I have to go - Sandra and the kid just came in. I'll talk to you later."

It's not the last conversation he had with his father, but it's the last one he rememebers. Subtle judgement, the smell of smoke and cold and stale Turkish coffee and all those little clear bells, ringing, ringing, ringing: Lazarus rising, just to fall a week later.

Novi Grad falls on his son's birthday, the 11th of April, the day before Easter. It takes everything else down with it.

This was not the first time Novi Grad had fallen. Historically, this wasn't even the first time it’d suffered this extent of loss of life. But it was the first time the ruins were cauterized before something could grow from in between them like weeds out the sidewalk. It was the first time that what was lost was acknowledged as such: dead, gone, our condolences for your loss. Nothing more to be done.

There’d been excuses, of course, and platitudes spoken by the feeble remaining government, echoes of the UN and NATO and the EU he'd learned to recognize as empty long before he started working in security consulting:

We empathize greatly with all Sokovian nationals in this trying time. We’re doing everything in our power to stabilize the situation. We’re doing everything we can to never let a catastrophe like this happen again. It’ll just take a few weeks, a month, a year or two or five to rebuild, but patience is of the essence here.

We’re all very horrified, you understand. There aren’t enough resources for everyone, you see. It’s a very complicated situation, there’s no one answer here – now’s not the time to be pointing fingers. But we’re doing everything we can. We’re sure it’ll be enough.

Daće Bog. That’s what his mother used to say – like a vague handwave to ward off all the legitimate fear and anxiety before it can ever take root in her body, in her home. If she saw even a glimpse of it in her son’s face she’d take it as a clear sign that she had personally failed somehow, which would, exacerbated by alcohol and pent-up emotion, upset and anger her more than the original problem itself. Zemo'd learned how to bury and snuff out these embers of fear very quickly.

There's talk of persecution of royalist dissidents abroad - God will protect us from the infidels, you'll see. The regime changes and the country plunges into economic crisis - so what, it'll pass, God willing, and then we'll be able to return. Yet another war breaks out, nothing but a parasitic twin to the last, devouring the country from the inside out and draining off fresh blood – well, it's nothing new. it'll be alright, God willing we'll get the bastards before they get us. Crkli dabogda.

And he’d just nod his little head and allow, very neutral, very acquiescing for the tender age of nine, thirteen, sixteen - sure, of course, it'll all be fine. Much later, he'd adjust the poorly-fitted camouflage greens that would squeeze too tight around his neck and say in that same steady tone of voice into the payphone receiver, Don't worry, mama, don't worry, it'll be taken care of. Daće Bog.

That’s all she’d ever say on the topic, or any topic really. God save us, God willing, God will provide – that was her eternal refrain. Well that and, just you wait until your father gets home, if she'd perceived him to be acting up somehow - more often than not by virtue of sheer existence alone.

This was, of course, yet another half-truth - his father never really took to beating him. There were always bigger things to worry about, things that belonged to the grander picture - too wide for him to fit into as an important variable and just manageable enough to squeeze into his young body like a manifestation of a future his father was pouring all his hope and dreams into.

Either way, the fear was there. The fear of disappointing, of coming up short to the ideal of what a son should be; it was all it took to keep him in line. Father, God – they became two sides of the same coin, the same promise of impending judgement. Both instilled far more trepidation in him than comfort.

It’s only when the bulldozer finally digs up what remains of their old country estate and he can pull his father’s unrecognizable, mangled body into his lap – so small and frail, when did his father get to be so small and frail? – that he thinks: what was I so afraid of all those years?

***

Excerpt from my Zemo character study - turned out to be much longer than a snippet, but I got carried away. Still very much a WIP, but thought I might as well post it until I figure out where I want to go with it.

Translations:

Daće bog - God will provide, God willing

Crkli dabogda - may they all die, God willing

gastarbeiter - (German) foreign or migrant worker

#VERY MUCH A WIP. jesus christ#i know zemo's wife and kid technically have german names in mcu canon but I've decided to ignore this#sokovian language and history heavily yet loosely based on yugoslavia with some mixing with other regional influences. to be developed#anyway! this needs so much work fml but the general idea's there.#helmut zemo#helmut zemo fic#my fic#ficlet

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

#antique#postage#postage stamps#stamps#photography#lightroom#tumblr photographer#macro#history#sscb#russia#yugoslavia

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today marks 32 years since the beginning of the Bosnian war.

I’m gonna include links for information and resources in this post.

Thousands of innocent civilians, mostly Bosniaks would be slaughtered, raped and/or interned by Yugoslav army troops, Bosnian Serb fascist militias and foreign volunteer mercenaries (mostly Russian and Greek christofascist types).

This would lead to the Bosnian genocide which consisted of atrocities such as the Srebrenica massacre where 8,372 men and boys would be killed en masse.

Among many other atrocities (too many to list here)

Atrocities which continue to be defended and/or denied by politicians among the Serbian far right, Bosnian Serbs, and far right fascist monsters in Europe, America, Israel and other places.

Including British loyalists in my own country, lionising figures like Miloševic and calling for my own people to be slaughtered like the Bosniaks. (Ironic since the UK they claim loyalty contributed troops and resources to the NATO and UNPROFOR missions against such forces in Yugoslavia at the same time)

Defending or denying such atrocities saying “tHe SErbS wERe ONLy deFEndinG THEir hOMeLanD¡” (if I hear another kebab removal joke I will NOT hesitate to get violent). Lionising the perpetrators in the process. Even to this day.

The war would end in 1995 with the signing of the Dayton Agreement. Which has since led to a lasting but uneasy peace but denialism still continues.

I’m including a few more links in a followup post too.

Reblog the shit out of this.

I bring this up because I study history myself.

#dougie rambles#personal stuff#history#yugoslavia#bosnia#bosnian war#bosnian genocide#srebrenica#war crimes#terrorism#genocide#denialism#yugoslav wars#reblog this#reblog the shit out of this#feel free to reblog#lemkin institute#raphael lemkin

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

As I begin the next chapter of research into my grandfather's journey through World War 2, I am focusing on his whereabouts betwen 1941 and 1945.

We believe some of this time was spent detained in a PoW camp, but we are not yet sure which one. We have a photo and anecdotal stories passed down the family. I also have a series of replies from official bodies saying they have no record of my grandfather.

During the height of the conflicts in Wolrd War 2, there were over 1000 camps for detainees, including Concentration Camps, Transit Camps and Prisoner of War Camps.

A needle in a haystack doesn't even begin to cover what I am trying find, and so to try and help narrow things down, and to provide some context and clairty of definitions, I am starting with some of the basics before investigating which camps he could possibly have been detained in.

What is a Prisoner of War?

A prisoner of war (PoW) is "A combatant who falls into the hands of an adverse party...in the course of an international armed conflict".

The rights afforded PoW's also stretches to civilians, so that any persons "who fall into the hands of the enemy during an armed conflict are protected under humanitarian law. If the individual is a combatant, he or she is accorded protection as a prisoner of war. If the individual is a civilian, he or she is protected as such." (Medecins Sans Frontieres)

Under the Geneva Convention, which at the time of Word War 2 was in its second iteration, and hence why I am flipping into past tense here, Prisoners of War and other civilian detainess were granted legal rights of protection.

To oversee these rights, the International Committe of the Red Cross (ICRC) were entrusted with a central role of "protecting the dignity and wellebing of PoWs". With the responsibility of monitoring conditions of those detained, the ICRC would attempt to visit camps and interview those detained.

However, during the Second World War, when attempting to access those captured by the Germans, this was not straightforward. German Red Cross had been pulled into being state owned and was no more than a puppet committee, and they did not comply with the ICRC's demands to visit detainees.

On 29 April 1942, the German Red Cross informed the ICRC that it would not communicate any information on "non-Aryan" detainees, and asked it to refrain from asking questions about them.

The ICRC have since acknowledged they were "impotent" during the Nazi regime.

So although no official records seem to exist for my grandfather thus far(acknowledging that I haven't completed all my investigations), I am slightly encouraged.

At first I felt that no records existed because he wasn't technically a PoW as he wasn't a combatant, which I assumed due to his age at this time. Of course it is possible he was a member of the Yugoslav Partisans at the age of 18 - we know that other members of our family were part of Tito's Partisan army.

However, it is just as possible, if not more likely, that he was captured by the Italians as a Slovene, and simply not visited by the Red Cross, especially given the difficulties they were having with Germany (which I read as all Axis powers).

Now I can understand why I have received responses From the ICRC stating that they have no known records of my grandfather during this time. I can also understand why no records exist from the former Yugoslavia, given this country no longer exists and many records were destroyed during the conflict of the early 1990s.

But with this clarity on the definitions surrounding Prisoners of War, along with this context and background of how PoWs were treated and monitored, I can start to find a way of narrowing down my searches and focus my investigations to find my grandfather in and amongst the historical chaos and confusion of the Second World War.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

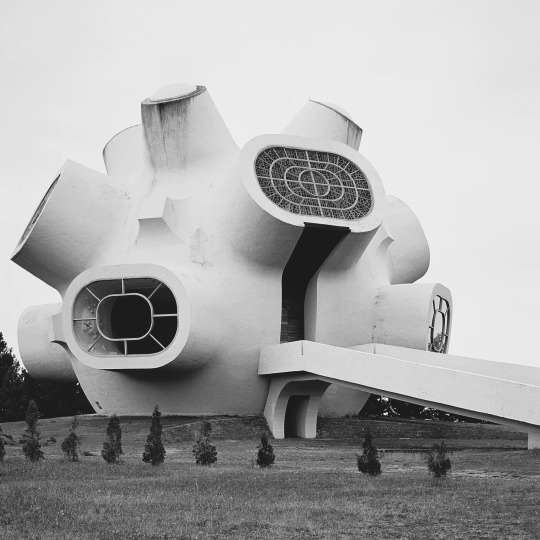

Monument Ilinden (Makedonium), Krushevo, Macedonia, designed by Jordan and Iskra Grabuloski.

(Architectural Digest)

308 notes

·

View notes

Text

Construction workers on "Assicurazioni Generali" building on Terazije, Belgrade, 1930. In the background Belgrade train station can be seen with Old Post Office building next to it.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Another one for the collection: home-made vest from Bosnia, another example of taking old Yugoslav Army M77 parkas and cutting them up. Magazine pouches are weirdly deep, most likely intended for either Thompson/PPsh or RPK magazines. Comfy and snug to wear though!

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Another poll about knowledge. Reblog and feel free to say how you know what you know, if you have any historical connections to the region.

#history#sort of (it happened in the 90s)#Yugoslavia#i know all the countries it is now#and consider myself somewhat knowledgeable about the process of the breakup#and I know what I know because of a podcast about nationalism#which triggered a category four autism moment

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

24 years on from March 24th 1999.

a poem by Dobrica Erić made in honor of Milica Rakić and all the children that were killed during the NATO bombing of Yugoslavia

we will not forgive you for what you did to our children

#nato agression#nato bombing#crimes against children#serbian history#serbian poetry#poetry#serbia#yugoslavia

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some additional links for info and Bosnian war resources I couldn’t include in the last post:

Feel free to reblog.

3 notes

·

View notes