Text

We’ve Moved!

Check out the new blog, Quarto Thinks!

0 notes

Text

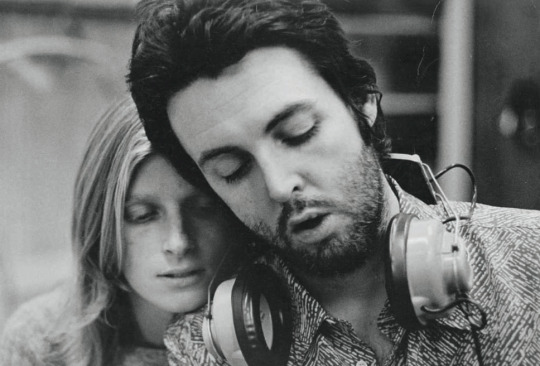

Sir Paul McCartney’s Solo Start

Recently, Paul McCartney has been rocking with Kanye and Rihanna. But where did his solo career start? The Beatles Solo documents his first career moves after Beatlemania.

If ever the world of music gave proof for the maxims “you always hurt the one you love” and“the road to hell is paved with good intentions,” it would be Paul McCartney and the Beatles. Though John was the Fab Four’s leader and founder, from 1966 it was Paul whose ambition, focus, and creativity increasingly drove and shaped the group. When John surrendered to his 1966–1967 LSD reverie, it was Paul whose songs filled the gaps left by John’s falling productivity. When the group, urged by George, stopped touring in 1966, it was Paul who came up with Sgt. Pepper as a project to give them a new world to conquer. When the Beatles’ manager, Brian Epstein, took his own life in August of 1967, it was Paul who insisted that making an unscripted road movie, Magical Mystery Tour, would cure them of the blues and confirm that the Beatles were still very much in business. When John fell headlong in love with Yoko Ono, installed her in the hitherto sacred space of the recording studio, and yet remained open to what the Beatles could do for his songs, it was Paul who asserted himself even more forcefully to have McCartney compositions performed the way he wanted in order to push the group to even greater heights.

This was Paul’s great mistake. Though there is no greater lover of harmony in music, Paul, paradoxically, had little gift for fostering harmony among his fellow musicians in the sessions for the so-called White Album. And despite the fact that the Beatles emerged with a masterpiece from those tense months in 1968, Paul was hardly wise to pressure the other three into the even more ambitious “Get Back” project, the back-to-basics movie/recording/ live-show rehearsals, where his perfectionism became even more overbearing to the other three as their doubts grew about Paul’s plans.

“After Brian died . . . Paul took over and supposedly led us. But what is leading us, when we went round in circles?” John said in 1970.

A very capable guitarist and drummer himself, Paul bruised the feelings of both Ringo and George in the way that he demanded adjustments to their playing, as if suddenly they were no longer quite good enough. (“We got fed up of being sidemen for Paul,” John added.) Paul, in short, was a control freak and, in another paradox for a musician with such a perfect ear, was surprisingly poor at listening to his friends.

Just as John had Yoko, Paul had another New York bohemian black sheep of a wealthy family, Linda Eastman. Whereas Linda never interfered in Paul’s music or his commitment to the Beatles, her family connections unwittingly created the circumstances by which the background tensions between Paul and the other three escalated into an acrimonious split.

New Jersey music-business accountant Allen Klein had flattered and seduced John Lennon into making him his business manager, with promises of vastly increasing the Beatles’ revenues. George and Ringo followed suit. They also voted to have him take charge of the running of their business, Apple Corps, which was out of control and hemorrhaging funds. Linda’s father and brother, John and Lee Eastman, were wealthy New York businessmen who had heard on the grapevine that Klein was not all that he seemed, and they counseled Paul to steer clear. Paul opposed the involvement of Klein in the Beatles’ affairs and urged the other three to let his new in-laws, the Eastmans, take charge instead. Seeing this suggestion as no more than a move by Paul to control every aspect of the group, they refused and got even more solidly behind their man Klein.

It turns out Paul’s judgment was right on target; however, his diplomacy was disastrous. Happily distracted by his marriage to the pregnant Linda in March of 1969, Paul could not finesse the feelings of his fellow Fabs. By that summer it was clear that, at the very least, the Beatles would be taking a break from each other while they tried to sort out their differences. In that spirit, the group recorded their final album proper, Abbey Road. Knowing that it may be their last for a while, the four pulled together one final time.

But no one, at that point, was saying that it was definitively over. Until two weeks before Abbey Road’s release, that is, when John announced to the other three that he was leaving. At that time, Klein was negotiating an enormous deal for the Beatles with Capitol Records, and he persuaded the four Beatles to keep John’s departure a secret until further notice.

Paul was distraught. At a draining time with the birth of his first child, Mary, that August, Paul found himself emotionally unprepared for the disintegration of the group he had poured himself into for years, as well as the fraying of friendships with all three, especially John, whom he continued to look up to even though he no longer understood what was going on in his old partner’s mind. Depressed and directionless, Paul later admitted that he hit the bottle at that time, and that only with Linda’s support did he recover the urge to make music. For years the studio perfectionist, now Paul was no longer trying to go bigger and better (and match the songs and productions of his friendly rival, Beach Boy Brian Wilson). Now, so roundly rejected by the other three Beatles, he would prove he didn’t need them. He would not only make a solo album, he would make it all by himself: writing, singing, playing, and recording every note. Only Linda would help him out with vocal harmonies—the controversial sound of things to come.

With no single, it would be an album of mostly casual, undercooked music making—just as Bob Dylan was also doing on the cusp between the 1960s and 1970s—entitled, in a stark declaration of self-sufficiency and independence, McCartney.

The fuss surrounding the album’s release upstaged the music itself. Paul wanted to release the album that spring of 1970, but the other three objected. Not only would it clash with the release of Ringo’s debut, Sentimental Journey, that March, but also with Let It Be, the Beatles album salvaged from the 1969 “Get Back” sessions by Wall of Sound producer Phil Spector, whose schmaltzy orchestration of his song “The Long and Winding Road” Paul loathed but could not veto. When John and George sent Ringo to Paul’s London home to ask him to delay the release of McCartney, Paul lost his temper and threw the drummer out.

It was all-out war now, which escalated when McCartney’s release was preceded by Paul’s wounded and coldly angry press release announcing to the world that he had left the Beatles, which made front-page news worldwide. Later, John remarked how smart Paul was to reveal the secret that the group was finished when he had a solo record to promote.

When the world heard the music behind the bombshell, they were underwhelmed—as were John and George, who voiced their disappointment in public. To most fans, only one song, “Maybe I’m Amazed,” sounded finished and a worthy addition to Paul’s songbook; the rest remained home-made sketches, or perhaps superior demos, as if Paul felt they weren’t worth any further work. But “Every Night,” which moves from angst to fulfillment in love, and the sadly nostalgic “Junk” are fine songs, and the remaining numbers, which include lo-fi instrumentals, are charming.

Such was the power of the Beatles’ brand that McCartney, with its back-cover photo of Paul with baby Mary, topped the U.S. album charts. Paul had gotten back on the horse, but he had a long way to go to meet public expectations. He spent much of 1970 and 1971 in a legal dispute with Allen Klein and the other Beatles as he tried to leave the partnership, exposing their commercial affairs and mutual grievances to a dismayed public, with many fans seeing Paul as the villain by suing his fellow former Beatles. By way of escape from the London High Court and lawyers’ offices, Paul and his family loved to retreat to his remote High Park Farm on the Mull of Kintyre, where he wrote a brand-new batch of songs.

The bitterness of the Beatles’ fallout, his rejuvenation at his spartan Scottish idyll, and his determination to make a proper, polished record now that he’d gotten over his depression, took Paul and Linda to her old apartment in New York. There they recorded, in semi-secrecy, a new album and stand-alone single that reflected the mixed picture of Paul’s life at the start of the 1970s.

Cut with a handful of excellent session players, Ram is a wonderful suite of singable, hummable McCartney melodies and sumptuous chord progressions.

Though none cohere into classic, self-contained songs to match “Maybe I’m Amazed,” never mind “Yesterday,” in mood and flow, Ram gets quite close to the bitty yet irresistible medley on the second side of Abbey Road. Though a vast overall improvement on Paul’s solo debut, Ram disappointed in two respects. First, Linda, who was pushed into the job of harmony singer by Paul, was no John or George, and from then on her often shrill and unsupple singing offered a poor substitute for the harmonic richness Paul’s fans had come to expect from his Beatles’ songs. (Linda was also cocredited as a songwriter on Ram, a legal fiction devised to help Paul earn royalties on a better publishing deal than that which he was tied into with the Lennon– McCartney partnership.) Second, without the friendly competition with the verbally exacting John to push wordsmith Paul the to memorable heights of wit and pathos, Paul’s lyric writing settled for glibness, whimsy, dippiness, and an occasionally carping tone that infuriated John when he rightly detected a finger-wagging criticism within the words of the album’s opener, “Too Many People.” John reacted by overreacting on his Imagine song “How Do You Sleep?”, which, nasty though it was, was written in blood and acid in contrast to the vanilla essence that flowed through Paul’s writing. (And just in case anyone missed the point: whereas Paul was photographed on the sleeve of Ram shearing a sheep at his Scottish farm, John had himself pictured straddling a pig on Imagine.)

Paul had written more good songs than would fit in one album, so “Another Day” was released as a stand-alone single; it’s a slice of an everywoman’s life that Paul had felt able to express beautifully before in “Eleanor Rigby” and “She’s Leaving Home.” Like Ram, it was catchy and attractive; also like Ram, the single did not reach his highest standards— far more a “Your Mother Should Know” than a “Hey Jude.”

Commercially, Paul hit the jackpot with both records, but then he had come to expect that as a matter of course over the years. But for Paul, without John there to test how far the public could be pushed before they stopped buying your records, big sales meant that he was pleasing people, and he was always eager to please the people. Indeed, in June of 1971, just after Ram’s release, he secretly (and expensively) rerecorded its tunes back at Abbey Road in middle-of-the-road big band and choir arrangements of the kind Paul felt his dad would enjoy. Titled Thrillington and credited to a fictional Percy “Thrills” Thrillington, this album of enjoyably undemanding light music was shelved until a belated release in 1977. Why? That summer of 1971 Paul had decided to form a new band.

---

#the beatles solo#sir paul mccartney#paul mccartney#macca#mat snow#music biography#music geek#music nerd#beatlemania#bassist

0 notes

Text

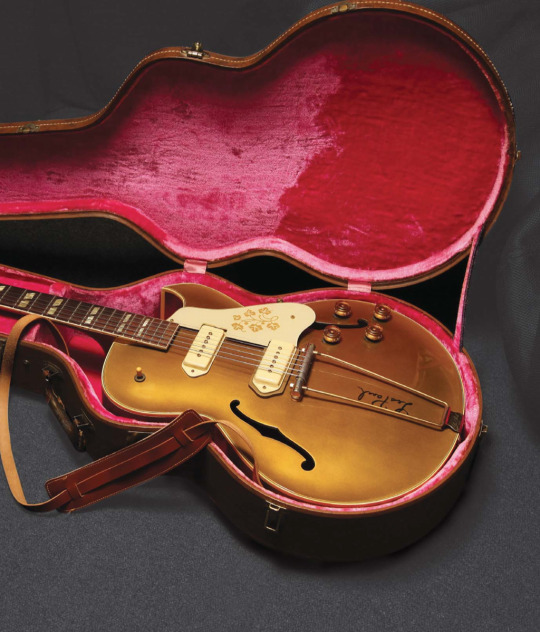

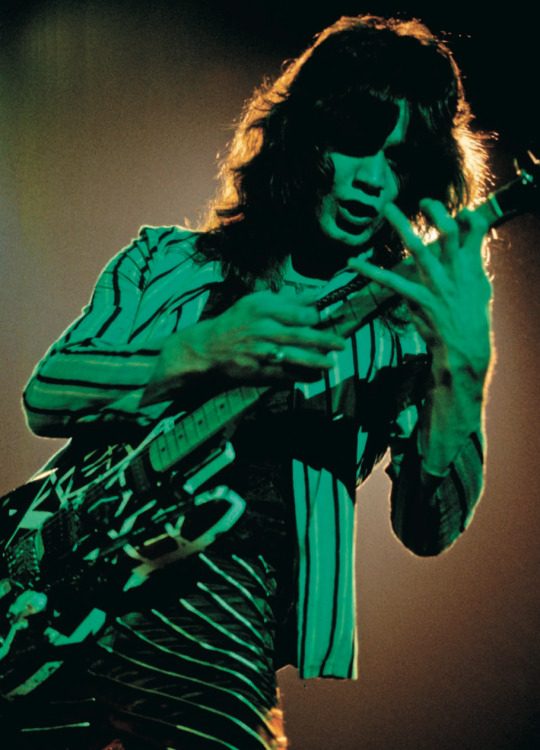

Neil Young’s Les Paul

Continuing our Les Paul celebration, Neil Young’s known as one of rock and roll’s greatest songwriters and performers, but what instrument did he use to get that accolade? The Gibson Les Paul tells you all about “Old Black”, Young’s favorite Les Paul.

A music fan of 1968 would have found Neil Young an odd candidate to be credited as a founder of the heavy-rock movement. Up to this point, his work with Buffalo Springfield and his self-titled solo debut (1968), all worked toward crafting his image as a country-rock originator and a moving force in the burgeoning singer/songwriter scene. With the release of his second solo album, Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere (1969), extended electric guitar workouts in songs like “Cinnamon Girl,” “Down by the River,” and “Cowgirl in the Sand” hinted at a more unhinged musical fury. Young’s stinging, slightly venomous musical persona—both sonic and thematic—continued to boil to the surface, first with a few tracks on the mostly folk- and country-informed After the Gold Rush (1970) and Harvest (1972), and more so on later releases like Zuma (1975), Rust Never Sleeps (1979), and Ragged Glory (1990). Though Young has long been associated with acoustic- flavored country rock, this is an artist who likes to rock—and when he does, he more often than not does so on a modified 1953 Gibson Les Paul known as “Old Black,” one of the quirkiest and most colorful guitars out there.

Young acquired Old Black from former Buffalo Springfield bandmate Jim Messina in 1969 (some accounts credit the former owner as Stephen Stills), by which time the Les Paul had already been thoroughly modified. Born with a classic early-1950s goldtop finish, it had been painted black by a previous owner. The original “wraparound” combined bridge and tail-piece had also been replaced by a Bigsby B7 vibrato/Gibson Tune-o-matic bridge combination. Apparently the guitar’s original neck or headstock had been replaced as well sometime in the ’60s, as evidenced by the SG/ES-335-style “crown” inlay found where the “Les Paul Model” logo would normally be seen. Other cosmetic alterations include pinstriping tape added to the back of the neck and body, and the aluminum pickguard that has replaced the original cream-colored plastic guard. More pertinent to its signature tone, though, is the addition of a Gibson Firebird mini-humbucking pickup in the bridge position, while the neck pickup is still the original P-90, though this has been updated with a metal cover over the years. An exceedingly lively pickup, this Firebird ’bucker, which Young’s long- time guitar tech Larry Cragg describes as microphonic, plays a big part in Young’s characteristic feedback-laden soloing assault. An additional toggle switch acts as a bypass, sending the Firebird pickup directly to Young’s amplifier.

Of course, some of the credit for Young’s distinct sound is owed to that amplifier: a modified 1959 tweed Fender Deluxe that has long been Young’s number-one amp. Young’s legendary, super-saturated overdrive sound is derived from Old Black injected straight into the Deluxe—other pedals are used for different effects, but none for added gain or distortion. Unprecedented control over the simple Deluxe’s three-knob control panel is afforded by a gizmo named “The Whizzer,” an automated unit built by Young’s late amp tech Sal Trentino in the late 1970s. The Whizzer can rotate volume and tone controls to four preset configurations with the stomp of a footswitch, to elicit subtle—and sometimes radical— changes in the amp’s performance. Add it up, and it’s a fierce assault enabled by relatively basic—and ancient—gear. And, as witnessed on albums and performances from 1969 to present, the rig proves more than enough to earn Young his “Godfather of Grunge” tag.

---

Buy from an Online Retailer

#The Gibson Les Paul#Les Paul#guitar#guitars#music geek#music nerd#neil young#musical instruments#music

1 note

·

View note

Text

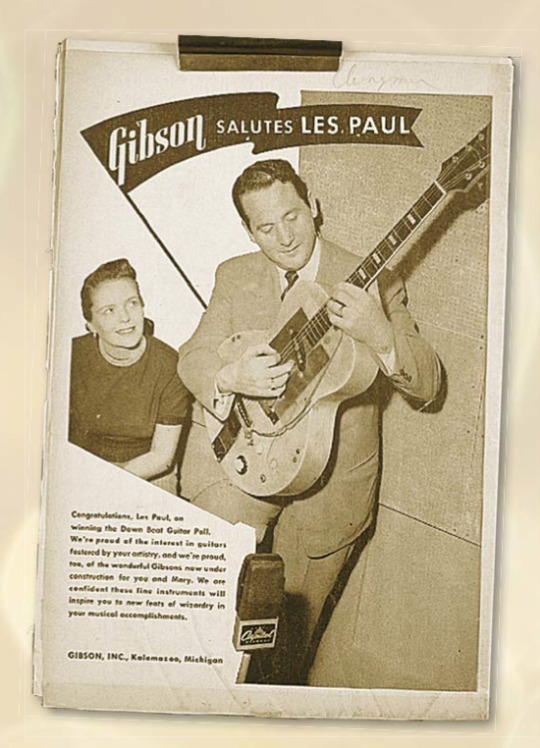

Les Paul Meets the Les Paul

Today marks the 100th Birthday of the late guitar legend, Les Paul. The Gibson Les Paul shares the story of how he lent his name to the Gibson guitar model.

One way or another, it seemed, all roads still led to Les Paul. In his conversations with writer Tom Wheeler, McCarty told the story of taking the prototype to Delaware Water Gap, Pennsylvania, a town about fifty miles outside New York City, where Les Paul had set up his recording studio. “Les played it, and his eyes lit up. We worked all night long on a royalty contract, and when we were finished, it was only a page-and-a-half long. After that we submitted things to Les for his advice.” As with any product in early development, several more iterations followed this prototype, all evolving toward a final commercial rendition in 1952, with a goldtop finish in place of the traditional sunburst, and a bridge-and-tailpiece unit based on one designed by Les himself, rather than the unit borrowed from Gibson’s larger hollowbody archtops.

The now-iconic goldtop finish—actually produced by add- ing bronze powder to a brew of clear nitrocellulose lacquer and reducer—was a wise bid to capture the attention of a new mood sweeping through the guitar world—one that would soon be defined simply as “rock ’n’ roll.” Whatever its supposed market appeal, Les has also claimed the finish to be his idea—the idea being to des- ignate the goldtop as a top-of-the-line electric guitar. (Somewhat contrary to this, perhaps, he also laid claim to the all-black coat worn by the “black-tie-dressed” Les Paul Custom of 1954, which was truly Gibson’s top-of-the-line solidbody electric for many years.) Apparently first used on a unique presentation model hollowbody in 1951, the gold finish also appeared on Gibson’s ES-295, which was also released in 1952 and quickly became iconic in rockabilly circles. That hollowbody electric was identical to the ES-175 except for its use of one significant piece of hardware: an integral bridge/ tailpiece unit designed by Les Paul himself, which also appeared on the inaugural run of Les Paul Model solidbody electric guitars, and which was later encored on the thinline hollowbody ES-225. The only problem—and it’s another great Les Paul irony—was that the bridge was used wrongly on the guitar that carried his name.

Les had designed the bridge back in 1945 or ’46 with the intention of enhancing sustain and minimizing unwanted body vibrations. He constructed it in the metal shop belonging to his neighbor Phil Wagner and used it on several of his own hollowbody electrics, and renditions of the log, for recordings and performances throughout the late ’40s, including studio dates with Bing Crosby. The bridge section was fashioned from a cylindrical metal rod with six holes for string anchors, a post at either end with thumb- wheel height adjustment, and long “trapeze” rods to anchor it at the butt-end of the guitar, in much the same way as a traditional trapeze tailpiece would be anchored. As used by Les, the strings were inserted through the anchor holes from the front of the bridge bar and wrapped around the top of the bar toward the fingerboard (as such, it was the true precursor to the “wraparound” bridge introduced in 1953—more of which later). As used by Gibson on the first batch of Les Pauls throughout 1952 and into ’53, however, its function was severely compromised.

“This is f---ed up,” Paul told The Guitar Magazine UK in February 2001, while displaying an original example. “The first arched-top body models were incorrectly made. The tailpiece is wrong, the neck joins the body wrong: it’s not on a bias, not on an angle. They thought, ‘Well, I guess what Les meant was the strings are supposed to go under the bridge.’ But you can’t muffle the strings at the bridge. They made this wrong. When I got this guitar, I said, ‘Stop it! You’re making the guitars all wrong!’ There may be a thousand of these guitars out there.” It’s also worth noting that Les Paul submitted his own patent application for the “Combined Bridge and Tailpiece for Stringed Instruments” (with the strings clearly wrapping over the bar) on July 9, 1952, and that it was granted on March 13, 1956, the year the ES-225 was introduced. The last guitar to carry that piece of hardware, it would be discontinued in 1959.

It might seem inconceivable that a well-established guitar maker like Gibson would make such a fundamental mistake on a major new model, and persist with the flaw through production numbers running into the four figures—Gibson’s shipping records show that 1,716 were produced in the first year, and many in early ’53 retained the same bridge—but several elements seem to have contributed to the prolonged gaff. For one, Les Paul himself was off on tour with Mary Ford for much of the time that the guitar was in production, and he didn’t receive his sample until plenty had come off the line (clearly, the assumption was that it would be much like the final prototype, but with his bridge added).

Back in Kalamazoo—according to accounts of firsthand encounters with key personnel related in Robb Lawrence’s book The Les Paul Legacy (Hal Leonard, 2008)—Gibson engineers were following the premise that the pickups should be set deep into the wood of the top to capture the body’s resonance, while also working with Les’s relatively high bridge design, which had presumably been tooled up and produced in great numbers. Put it all together, however, and the only way to make the thing playable was to wrap the strings under the bridge bar. You could no longer palm-mute the strings at the edge of the bridge the way Les and some other accomplished players liked to do, but the guitar still functioned.

In addition to the shallow neck pitch and incorrectly used tailpiece, some of the very earliest Les Paul Models had unbound rosewood fingerboards, as opposed to the bound boards that have become the norm. The very earliest also had the P-90 in the bridge position mounted with screws running through diagonally opposite corners of the cover and bobbin, rather than between the A and D and the G and B poles (as on the neck P-90, as well as the standard bridge units that followed shortly after). Soon, however, Gibson settled into the more common first-run goldtops, which were produced from around spring of 1952 into early or mid-’53. Unlike many collectible vintage guitars, these have never garnered as much excitement as have examples from throughout the rest of the decade, thanks to the flat neck angle and “wrong” bridge installation. Often more affordable on the vintage market than their successors, these debutante Les Pauls are sometimes converted by their owners, some of whom add “wrap-over” bridges (ground down to fit the low neck pitch) or even reset the necks to make them more like Les Pauls from the mid-to-late ’50s.

---

#the gibson les paul#gibson les paul#les paul#guitar#guitars#music#music geek#music nerd#les paul 100th anniversary

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Stay in touch with your friends.... or your enemies with these Breaking Bad postcards!

Get ‘em now!

Buy from an Online Retailer

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

The History of Drones

Drones have come a long way since they were first created almost a century ago. Today when we talk about drones, we could be referring to military operations or Amazon newest delivery service plans. Area 51: Black Jets shares the history of the drone at the famous U.S. Air Force facility.

The Lockheed Martin P-175 Polecat was a worthy successor to the reconnaissance aircraft projects that had come to Groom Lake from the Skunk Works through the decades. Illustration by Erik Simonsen.

In the world of popular interest in aviation, the first decade of the twenty-first century could be called the Decade of the Drone. Certainly the drone has become synonymous with clandestine military operations in places such as Afghanistan and Pakistan.These aircraft, called RPVs in the third quarter of the last century and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV) more recently, were first widely used for aerial reconnaissance missions during the war in Southeast Asia and for combat operations since the turn of the century.

However, drones have been around for almost a century.The first military drone designed for combat, the Kettering Bug, was being tested in 1918 and might have played a role in World War I had that conflict not ended when it did. By midcentury, the hobby of flying remotely controlled airplanes was widespread. During World War II, an enterprising Californian named Reginald Denny started a company called Radioplane, which sold thousands of scaled-up radio-controlled models to the US Army and US Navy as target drones. Northrop later bought Radioplane and continued building both piston-engine and jet target drones.

After World War II, as discussed in chapter 12, Ryan Aeronautical (later Teledyne Ryan) developed a line of jet-propelled target drones that were called Firebees. In turn, these were adapted for reconnaissance missions over North Vietnam, Laos, and elsewhere during the 1960s, propelling the company down a path toward more sophisticated RPV reconnaissance aircraft such as Compass, Compass Cope, and Patent Number 4019699.

By the 1990s, as RPVs were now being called UAVs, they were growing in sophistication. Many surveillance drones in service then, as now, such as the RQ-2 Pioneer, RQ-5 Hunter, or Boeing Insitu ScanEagle, were small, slow, piston-engine aircraft. Others are larger and much more sophisticated.Teledyne Ryan’s experience with the Compass Cope, for example, led to the RQ-4 Global Hawk, a large jet aircraft that can operate at 60,000 feet and stay aloft for more than 24 hours.

Drones captured the headlines after 2001, not only for their reconnaissance capability, but also for their offensive capabilities.Arming the General Atomics RQ-1 Predator with Hellfire missiles to take out terrorists and insurgents came as an afterthought to its original concept. However, when operations were watching the enemy in real-time video feeds, there was a natural inclination to attack the enemy that could be seen.The reconnaissance RQ-1 became the armed, multimission MQ-1, and General Atomics developed the much larger and more capable MQ-9 Reaper, which was capable of carrying more and varied offensive ordnance.

In the meantime, in 1998, DARPA and the US Air Force had initiated the Unmanned Combat Air Vehicle (UCAV) program, aimed at demonstrating unmanned stealth aircraft that could be flown on deep penetration missions, such as suppression of enemy air defenses, into heavily defended air space.This led to the Boeing Phantom Works X-45A, first flown in 2002, and the Northrop Grumman X-47A Pegasus, which made its debut in 2003.

Under the program, the Phantom Works project utilized technology from the Bird of Prey, while the X-47A would have benefited from the obscure Teledyne Ryan 4019699 research.

The UCAV program later became the Joint Unmanned Combat Air System (J-UCAS). The “J” was inserted when the US Navy expressed keen interest in the previously US Air Force program, specifically in the X-47A. Meanwhile, UCAV became UCAS when the DOD decided to consider the overall system developed within a program, not just the vehicle. Meanwhile the term UAS was introduced to supersede UAV, although in practice the UAV acronym continued to prevail.

The “white world” X-45A and X-47A never inhabited that arcane world where their existence was denied and are not known to have been tested in the skies over Area 51. However both projects involved technology that suggests that they may have “black world” cousins whose existence may not be disclosed for decades.

The future of aerial combat predicted at the turn of the century was embodied by the X-45A UCAV prototype, seen here at the Dryden Flight Research Center in 2001. DARPA.

One unmanned aircraft definitely straddles that line in the Lockheed Martin RQ-3 DarkStar, which brings the narrative full circle and back to the Skunk Works. Indeed, the DarkStar has evolved into programs that are known to have been seen over Area 51 and to others that simply remain unknown.

The DarkStar originated as Lockheed’s entry in DARPA’s High Altitude Endurance (HAE) UAV advanced airborne reconnaissance program, which was initiated in 1993 and which DARPA managed on behalf of the Defense Airborne Reconnaissance Office (DARO). HAE had evolved out of DARPA’s High-Altitude, Long-Endurance (HALE) program of the 1980s that led to the development of the Boeing Condor, a huge UAV with a service ceiling of 67,000 feet.

During the 1990s, each of the armed services developed a complicated and confusing taxonomy of “tiers” to define its UAV program, but this practice fell out of use in later years, probably because the respective nomenclature of the services did not align, and within the services, the drones themselves did not conform precisely to the tiers.The two complementary US Air Force aircraft developed under HAE were described not as Tier II and Tier III, but as Tier II Plus and Tier III Minus.Tier II Plus identified a strategic UAV operating up to 65,000 feet with a range of 3,000 miles, slightly beyond the performance envelope of Tier II.Tier III Minus UAVs were strategic HAE vehicles embodying LO characteristics, but they had a shorter endurance than Tier II Plus or Tier III aircraft.

Under HAE, the Tier II Plus aircraft was the RQ-4 Global Hawk, while the Tier III Minus was the RQ-3 DarkStar. Both were intended to be reconnaissance aircraft, not UCAVs.The DarkStar first flew in 1996, while the RQ-4 Global Hawk first flew in 1998. The Global Hawk was a longer endurance, higher flying aircraft, while the DarkStar was designed as a stealth aircraft capable of operating in hostile environments.

While elements of the Global Hawk’s ongoing twenty-first century operational career remain classified, it has been widely photographed and was never a black program. The DarkStar, meanwhile, came and went quickly, leaving much speculation about follow-on aircraft.

Resembling a “flying saucer” from the front, the DarkStar airframe was composed primarily of nonmetal composites, and it had no vertical tail surfaces. It was only 15 feet from front to back, but its wing spanned 69 feet.The DarkStar had a gross weight of 8,600 pounds and was powered by a single Williams FJ-44-1 turbofan engine. It had an endurance of 12.7 hours, or eight hours above 45,000 feet.

The first DarkStar prototype made a successful debut flight in March 1996 at Edwards AFB but crashed on its second flight a month later.After twenty-six months of reworking, the second DarkStar made a forty-four-minute fully autonomous first flight in June 1998, but the Defense Department officially terminated the Tier III Minus program in January 1999. By this time, it seemed that there was more interest in the potential usefulness of a long range Global Hawk than a stealthy DarkStar.

---

#area 51 black jets#area 51#drones#history of drones#military#military history#Aviation#military aviation

0 notes

Text

Journal with Poe

Edgar Allan Poe is a renowned poet and storyteller who paved the way for many writers after him. If you’re looking for some inspiration with your writing, try out these pages from The Edgar Allan Poe Keepsake Journal.

One of the most iconic literary figures in the world, Edgar Allan Poe (1809–1849) was an author and poet who not only helped shape and define the genre of

American macabre, but was one of the first American writers to become a major figure in international literature.

Poe is considered a pioneer of literary horror with classics such as “The Tell-Tale Heart,” “Fall of the House of Usher,” and “The Raven.” He was also an inspiration to favorite authors including H.P. Lovecraft, Jules Verne, Charles Baudelaire, and Stephen King.

Although his name has become synonymous with horrific frights, premature burial, ancient crypts, and vengeful black cats, Poe was a major contributor to science fiction and an early practitioner of the craft of the short story. A master storyteller, Poe is also known as the inventor of detective fiction who paved the way for characters like Sherlock Holmes and Hercule Poirot.

Poe’s effect on pop culture and the public permeates beyond his poetry, fiction, and essays. Examples of Poe’s influence have appeared in a broad spectrum of mediums including film, comics, books, theatre, radio, and television. From a film based on the “The Raven” starring actor John Cusak as Poe himself, to an Italian comic book featuring a Poe protagonist with the code name “Raven,” the influence of Edgar Allen Poe continues to grow and nurture yet another generation.

Edgar Allan Poe’s own life was not any less intriguing than his work. To this day, his death remains a mystery. The cause of his death is unknown, but speculation has included delirium tremens, rabies, syphilis, and cholera. Regardless, his legacy is one that changed the world.

---

Buy from an Online Retailer

#the edgar allan poe keepsake journal#edgar allan poe#horror#literature#literacy#the raven#literary geek#literary nerd#classics#classic literature#journal#writing#writing tips

0 notes

Text

What Makes a Cult Classic?

Chances are you’re a fan of a cult film. But what does it take for a movie to considered one? The Big Lebowski: An Illustrated, Annotated History of the Greatest Cult Film of All Time takes a look at the different types of cult classics and what a movie needs to become one.

Not all cult films follow the same formula. Some are movies so bad they’re good. Attack of the Killer Tomatoes! (1978), with its legion of evil yet utterly nonthreatening squishy vegetables, is an archetypal example, but the contemporary Showgirls, which swept the 1995 Razzie awards, fits the bill just as well. These are films whose makers took themselves seriously, whereas 1975’s Rocky Horror Picture Show (the film that should have its photo in the dictionary next to “cult movie”) actually had fun at its own expense, embracing the campiness of the plot and acting. The film spawned a phenomenon of midnight theater showings, accompanied by audience costumes and antics orchestrated to specific moments in the narrative; these showings continue to this day. Despite some measure of critical disagreement about its worth at the time of its release, The Big Lebowski was never truly considered a “bad” film along the lines of these movies.

Showgirls, starring Elizabeth Berkley, is in the so-bad-its-good category.

Cult films are often created outside of the mainstream Hollywood apparatus or are somehow distinctive or experimental in their techniques or plot structures. Rocky Horror, with its mélange of musical, transvestite, sci-fi, and sexualized elements, is a good example, as is David Lynch’s Eraserhead (1977), with its bizarre narrative; grotesque, creature-like characters; and eerie sound design. While The Big Lebowski is certainly uncommon in many ways, it was distributed through the widely known Universal Pictures, and it had recognizable actors and a plot that, while unusual, wasn’t terribly unconventional.

Because of its decades of midnight showings, The Rocky Horror Picture Show has had the longest theatrical run in movie history.

Another defining characteristic of cult films is a rabid fan base that is either small or specialized, or both, in its makeup. Lebowski has a broad and extensive fan base, and while it skews somewhat younger, male, and white, its devotees are from all walks of life, cross- ing economic lines with both white and blue collars, academics and the undereducated. A high percentage of people (well, white men) on the dating website OkCupid who list The Big Lebowski as a favorite film also cite NASCAR as a main interest—a little perplexing in light of the movie’s hero, a liberal slacker. On the other hand, there are stories of those who have incorporated the movie into their job interview process and professionals who have made careers out of giving sales presentations and symposiums using the language of Lebowski. So while rabid, the broad swath of Lebowski followers are not a small, distinct group.

As it doesn’t fit any of the aforementioned criteria, what argument can be made for The Big Lebowski as the ultimate in cult filmdom?

—

#the big lebowski#cult films#cult classic#movie geek#movie nerd#the dude#showgirls#rocky horror picture show#movies#cult filmdom

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

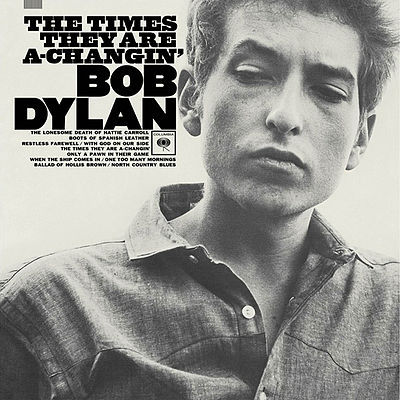

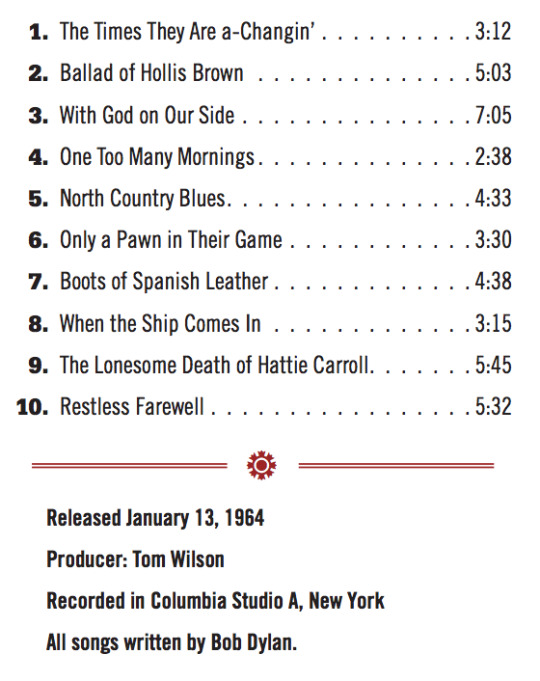

The Times They Are A-Changin’

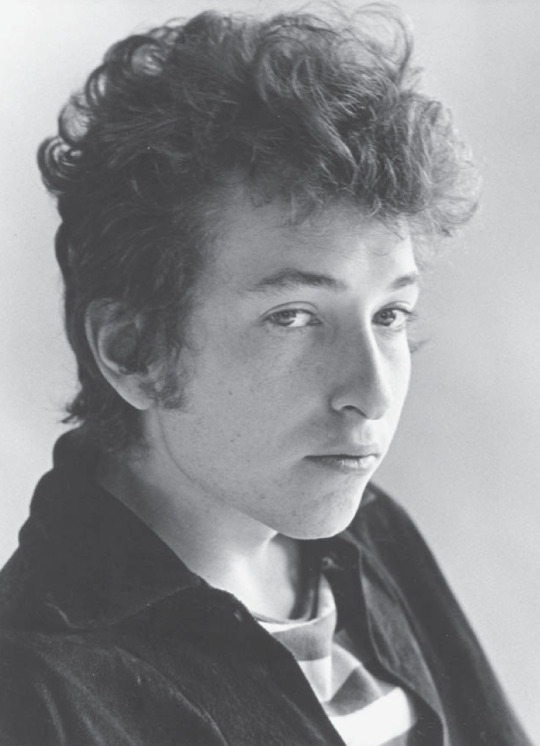

Happy Birthday to Bob Dylan! In celebration, let’s take a look at one of Dylan’s classic albums from Dylan Disc by Disc.

Although Dylan has often been labeled a protest singer, the period in which protest songs were a big part of his repertoire was fairly brief. Such songs were a major factor, however, in establishing his folk stardom and cementing his image, whether he wanted it or not, as a spokesperson for his generation. No other album captures this phase of his career as strongly as The Times They Are a-Changin’; the title song is one of the most famous protest songs of all time.

When the album was recorded between August and October 1963, things were changing fast not just in the world at large but also for Dylan himself. The release of his second album, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, in spring 1963 had vaulted him into national stardom. Folk star Joan Baez, by featuring Dylan’s songs in her concerts and albums, and also allowing him to share the stage at events like the 1963 Newport Folk Festival, exposed him to a wider audience than he could ever have hoped to reach on his own. The pair also appeared together that summer at the March on Washington, affirming his commitment to social justice in action as well as song.

The first of his albums to feature only original compositions, The Times They Are a-Changin’ was awash in tunes commenting upon, and at times railing against, social inequity, racism, and the madness of war. “With God on Our Side” attacked the hypocrisy of warmongers the world over, “Only a Pawn in Their Game” was inspired by the murder of civil rights activist Medgar Evers, and “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll” was based on the death of an African-American barmaid. The song “The Times They Are a-Changin’” was itself a declaration that a new generation of baby boomers had emerged to usher in a new way of looking at society.

Yet, like The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, the album balanced the diatribes with gentler, more personal ruminations. “Boots of Spanish Leather” reflected the ups and downs of his relationship with Suze Rotolo; “One Too Many Mornings” had a world-weary poetry that couldn’t be tied to any cause in particular. “Restless Farewell” hinted at a restlessness to move on—as he would, indeed, on his next album, leaving protest itself behind.

When The Times They Are a-Changin’ was released in January 1964, however, Dylan was still very much viewed as folk’s foremost topical songwriter. In accordance with his rising status, it became his first album to reach the Top Twenty. But much had changed after “Restless Farewell” concluded the LP’s sessions on Halloween 1963. President John F. Kennedy had been assassinated, puncturing the idealism of youthful activists across the globe. The singer’s romance with muse Rotolo was coming to an end. And the Beatles’ “I Want to Hold Your Hand” was rocketing to #1 in the United States, ushering in a new phase of both musical and cultural change that would impact Dylan and the rest of the music world.

---

#bob dylan#dylan disc by disc#the times they are a-changin'#music biography#music geek#music nerd#folk and traditional#rock#music

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

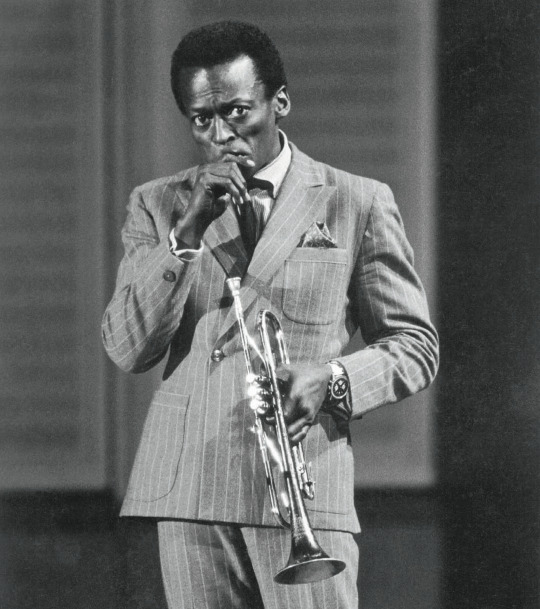

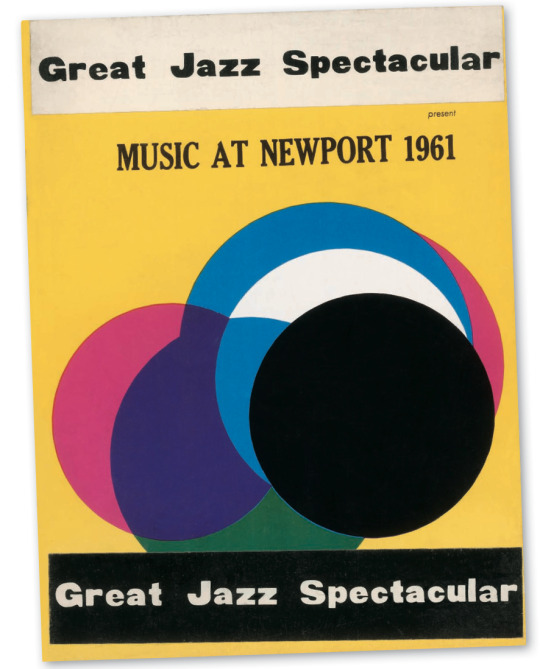

Miles, Newport, and the Business of Jazz

Happy International Jazz Day! What better way to celebrate than with a great story about an incredible jazz musician from Miles Davis: The Complete Illustrated History.

Early in 1952, Storyville At New Haven, a club I opened for a disastrous few weeks, welcomed a sextet that had been organized by Symphony Sid (Torin). Sid was the voice behind the live radio broadcasts from Birdland. He had worked with Shaw Artists to set up a tour for his bebop all-stars. The group consisted of Jimmy Heath on tenor saxophone, his brother Percy on bass, J. J. Johnson on trombone, Milt Jackson on vibraphone, Kenny Clarke on drums, and Miles Davis on trumpet.

At the beginning of the engagement, Symphony Sid told me not to give Miles any money. I was paying the group $1,200 for the week—from which all of their expenses, including Sid’s managerial fee and the agent’s percentage, were being extracted. I paid this amount directly to Sid, and he paid the musicians. Miles, who was deep into drugs at this time, probably owed Sid some money from their last gig.

Later that same night, Miles approached me.

“George,” he said, “give me ten dollars.”

“Sid told me not to give you any money, Miles. I can’t do it.” “George,” he said, as if he hadn’t heard me, “give me five dollars.” “Come on, Miles, I can’t do it. The man said not to give you any bread.”

“George, give me a dollar.”

“Miles—“

“Give me fifty cents, George. Give me a quarter. George, give me a penny.”

That was my first conversation with Miles Davis.

In 1955, during a trip to New York City that spring while I was planning the second Newport Jazz Festival, I stopped by the Basin Street East club. Miles Davis was sitting alone at a table in the corner. When Miles had played Storyville At New Haven, he’d been a pain in the ass. We didn’t have much of a relationship. But when I walked into the club, he called me over and asked a question.

“Are you having a jazz festival up at Newport this year?”

“Yeah, Miles,” I replied.

He looked me in the face and rasped: “You can’t have a jazz festival without me.”

“Miles,” I said, “do you want to come to Newport?”

“You can’t have a jazz festival without me,” he repeated.

“If you want to be there, I’ll call Jack,” I said. Jack Whittemore was Miles’ agent.

“You can’t have a jazz festival without me,” he said again. Miles had a way of getting his point across. Although I had already sketched out the program, I knew that I would somehow fit him onto the bill. Miles was in better physical shape in 1955 than he had been in recent years. But he didn’t have a working group. The economics of jazz were such that it was difficult for anyone to keep a band. Players took whatever work they could get. So I added Miles onto a jam session that already featured Zoot Sims on tenor saxophone, Gerry Mulligan on baritone, and Thelonious Monk on piano. These musicians were all willing to work as individual artists, without their respective groups. Percy Heath and Connie Kay were already scheduled to play earlier in the same program with the Modern Jazz Quartet, so I asked them to serve as the rhythm section.

Because of his late addition to the festival, Davis’ name wasn’t even printed in our program book. But his presence was felt that night. He overcame the inadequacies of the sound system by putting the microphone right into the bell of his trumpet—and playing Monk’s “Round Midnight.” The clarity of his sound pierced the air over Newport’s Freebody Park like nothing else we heard onstage that year. It was electrifying for the audience out on the grass, the musicians backstage, and the critics—some of whom had opined that Miles’ career was already over.

In his autobiography, Miles claims to have played “Round Midnight” with a mute. This was the way he would record it a few years later on ’Round About Midnight for Columbia Records. But he played the ballad with an open horn that night at Newport. My memory is as clear on that point as the sound that rang from the bell of the horn. Bootleg recordings of the jam session, taped from a Voice of America broadcast, confirm my recollection.

A point of interest in these tapes is that Miles does not appear to play well with Monk comping behind him (in “Hackensack”). When Monk lays out, Miles swings easily—“Now’s the Time.”

Miles also writes about how he had struggled with “Round Midnight” for a long time. Newport marked his victory over the tune. “When I got off the bandstand,” he writes, “everybody was looking at me like I was a king or something—people were running up to me offering me record deals. All the musicians there were treating me like I was a god, and all for a solo that I had had trouble learning a long time ago. It was something else, man, looking out at all those people and then seeing them suddenly standing up and applauding for what I had done.”

As Miles descended from the stage, he passed by me. His only words were in the form of a complaint: “Monk plays the wrong changes to ‘Round Midnight.’ ”

I laughed. “Miles, what do you want? He wrote the song!”

Miles Davis had the jazz world in his pocket at that moment, and he knew it. He handled it with characteristic aplomb. But even Miles couldn’t ignore the fact that this single performance had energized his entire career. His Newport appearance led to the beginning of what would be a longstanding relationship with Columbia Records. The fact that his comeback took place on the Newport stage helped to validate the festival among the jazz elite. In this way, July 17, 1955, was a good night for both of us.

---

#miles davis#international jazz day#jazz#jazz music#miles davis the complete illustrated history#music nerd#trumpet#newport#kind of blue#music biography#music geek

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

NWOBHM

The New Wave of British Heavy Metal hit in 1980, and The Big Book of Hair Metal has the timeline.

In 1980, the New Wave of British Heavy Metal (NWOBHM) is starting to mean something, with tons of fast, flash metal acts getting into the game, the most potentially hair metal of which is Def Leppard. Meanwhile, l.a. is starting to heat up, with bands frantically trying to get gigs, flyering, trading members, living off the avails of their low- level groupies, trying to make sense of a town that is still somewhere between post-punk, skinny-tie new wave, and the last vestiges of “glitter rock,” a term that essentially means glam but somehow applies more so to the handful of american bands making fools of themselves. bottom line: significantly, all the big Us hard rock bands (save for blue Öyster cult?!) have run out of gas around this time, and the UK behemoths aren’t faring any better. Just as there needs to be a NWOBHM, it looks like a young wave of american rockers are about to take over for the likes of yer wilting KISS, Aerosmith, and Deadly Tedly.

1980: Female metal band Vixen forms in St. Paul, Minnesota.

1980: Mickey Ratt moves from San Diego to L.A.

1980: Jon Bon Jovi is onto his third band, The Rest, after playing with Atlantic City Expressway and John Bon Jovi and the Wild Ones.

January 1980: The UK’s Girl unwittingly contributes to the invention of hair metal with their pouty, androgynous first album, Sheer Greed. The band features Phil Collen, later of Def Leppard, and Phil Lewis, later of L.A. Guns.

March 14, 1980: Def Leppard’s debut album, On Through the Night, considered the most Americanized, professional, and accomplished of all NWOBHM albums, a pointer toward the next metal trend. It would be certified platinum on May 9, 1989. The band somewhat disowns it, considering High ’n’ Dry their first “good” album. On Through the Night was produced by Tom Allom, known for commercializing Judas Priest.

March 26, 1980: Van Halen’s third album, Women and Children First, is released.

March 28, 1980: Vancouver’s Loverboy help pioneer the hair metal sound and look with a string of party rock anthems on their self-titled double platinum debut. Hits include “Turn Me Loose,” “The Kid Is Hot Tonite,” and “Working for the Weekend.”

August 22–24, 1980: Def Leppard play the Reading Festival in England. Already there is a slight backlash brewing to the band’s Americanized sound.

---

#hair metal#the big book of hair metal#1980#80s rock#rock n roll#rock music#def leppard#music#music geek#music nerd

0 notes

Text

Dude, Where’s My...TARDIS?

What would Doctor Who be without the TARDIS? Unofficial Doctor Who Big Book of Lists takes a look at the few episodes that did not feature the iconic TARDIS.

In the world of Doctor Who, we met the TARDIS before we even met the Doctor. And yet, there are some episodes—in fact, some complete stories—where the old girl is nowhere to be seen. It doesn’t bear thinking about, I know, but here are those offending adventures that didn’t feature Doctor Who’s most iconic feature, the TARDIS.

“Mission to the Unknown” (1965)

This one-part story (which acted as a prelude to “The Daleks’ Master Plan”) not only had the audacity not to include the TARDIS, but it also neglected to feature the Doctor or any of his companions!

“Doctor Who and the Silurians” (1970)

It would be a few years until the production team dared to forget the Time Lord’s ship of choice,and it was in this Jon Pertwee eco-tale where it was ignored. To make up for it, they stuck the name of the show in the name of the episode (they wouldn’t do that again for a while).

“The Sea Devils” (1972)

Just two years later in this six-parter, also featuring Pertwee, we saw the appearance of the Silurian’s amphibious cousins, the “Sea Devils.” The absence of the TARDIS is compensated for in a delicious scheme by the Master.

“The Sontaran Experiment” (1975)

Just a little later,withTom Baker in charge and traveling with Sarah Jane Smith and Harry Sullivan, the gang used a transmit beam from the Nerva Beacon to Earth (thirtieth century, apparently). Pity for them, as using the TARDIS would have probably meant they wouldn’t have come into contact with those nasty Sontarans.

“Genesis of the Daleks” (1975)

And, blimey, in the very next story, there was no TARDIS love either (a great disadvantage in this story, having to rely on the Gallifreyan Time Ring). Interesting that such a well-loved story (always in top 10 favorites of all time lineups) doesn’t feature the Doctor’s BFF. By the end of this story, fans had been without the TARDIS for eight episodes. Utterly shocking.

“Midnight” (2008)

And finally the most recent episode on this list, the David Tennant outing “Midnight.” Again, the Doctor could really have done with the TARDIS here to get away from his rather unpleasant traveling companions. Russell T. Davies also did away with the companion (Donna Noble) in this story, along with the Doctor’s voice. The fiend!

---

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

www.quartoknows.com

#Quarto Knows#Quarto Thinks#Qgeekbooks#be in the know#beintheknow#culture#music#pop culture#literature#classic literature#classic#classic rock#art#geek#nerd#humor#fiction

0 notes

Text

Must Watch: Indie Rock Documentaries

If you’re looking for some good documentaries about the 80s-90s underground rock scene, the films on this list from Gimme Indie Rock are incredible. Check them out!

Many of the bands featured in these pages have been the subjects of feature-length documentaries. While some of docs cannot be wholeheartedly recommended due to the general problems that plague the rock-doc format (or because I simply have not seen them), the following come highly recommended. Please note: aside from 1991: The Year Punk Broke, these are not “tour docs,” though many of those exist as well.

1991: The Year Punk Broke

Another State of Mind (1982 hardcore; Social Distortion, Youth Brigade, Minor Threat)

Athens, GA: Inside/Out

The Color of Noise: The Amphetamine Reptile Records Story

Couldn’t You Wait: The Story of Silkworm

The Decline of Western Civilization (1980s L.A. punk)

The Devil and Daniel Johnston

Don’t Need You: The Herstory of Riot Grrrl!

The Fearless Freaks (the Flaming Lips) Filmage: The Story of the Descendents

First Avenue Hayday (Minneapolis nightclub)

Fugazi: Instrument

Guided By Voices: Watch Me Jumpstart

Half Japanese: The Band That Would Be King

Hype! (Seattle scene documentary made in 1996)

Not a Photograph: The Mission of Burma Story Sonic Outlaws (Negativland & friends)

Such Hawks Such Hounds: The American Hard Rock Underground

Tad: Busted Circuits and Ringing Ears

We Jam Econo: The Story of the Minutemen

---

Buy from an Online Retailer

#gimme indie rock#indie rock#underground rock#music geek#music nerd#documentaries#music documentary#punk#punk rock#music history

0 notes

Text

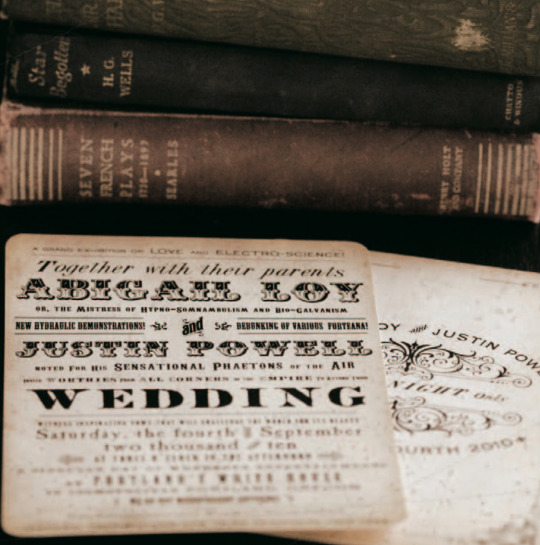

Steampunk Invites

It’s the season of celebrations. From weddings to graduation parties, make your invitations stand out with these steampunk inspired ideas from 1000 Steampunk Creations!

Royal Steamline, USA

Royal Steamline, USA

Royal Steamline, USA

Royal Steamline, USA

---

#steampunk#1000 steampunk creations#steampunk invitations#science fiction#victorian#invitations#dr grymm

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Can you caption this gorgeous illustration from The Secret Garden Unfolded?

You could win the whole collection!

Get them now for Mother’s Day!

#classics#Illustration#great illustrated classics#illustrated classics#classics unfolded#the secret garden#caption contest#literature#classic literature#literary

0 notes