#editing advice

Text

Cut out the boring bits

If you are bored when writing a scene, then chances are, that scene will be boring for readers.

If you find yourself bored, take a step back and analyse why. How can you improve it, and if you can’t, is it necessary for your plot?

#quick writing tips#writers#creative writing#writing#writing community#writers of tumblr#creative writers#writing inspiration#writeblr#writerblr#writing tips#writblr#writers corner#nanowrimo#national novel writing month#nanowrimo 2023#nano 2023#let's write#story editing#editing advice#editing tips#tips for writers#helping writers#plot development

689 notes

·

View notes

Text

How to Survive the Editing Process

Writing a first draft takes so much of your time and energy. When you finish something, celebrate your accomplishment! It’s proof of your creativity and hard work.

If you want people to read your work, then it’s time to edit.

Editing can seem scary. Daunting. Confusing.

Use these tips to get started.

1. Take a Break from Your Work

It’s so important to let your brain reset after finishing any story. Close your draft and spend the next few days or weeks doing other hobbies. When you feel ready to return with a newly energized, distanced perspective, you’ll get your best editing work done.

2. Start With Developmental Editing

Writers often think that they have to start editing line by line, looking for grammar and spelling issues. While you’re free to do that, you’re likely going to add and remove plenty of content before your final draft is done.

Instead, start with developmental editing. Read through your work and take notes about how the larger plot points are working or not working. Does each chapter move your characters through each point on your plot outline or your visualized storyline?

This step may involve adding new scenes or removing others. It can also mean reworking old scenes so they’re less wordy, more descriptive, more actionable, or whatever you feel like is missing.

Take notes about plot holes too. You don’t have to fix them on your first read-through, but note where they’re happening and why they’re holes. You can return in your second read-through to address them.

You can also break your developmental editing into questions, like:

What is my story’s theme and does each chapter support that theme?

What does every character want and do they achieve that? Why or why not?

What motivates each character? Do they retain that motivation or develop a new one to better serve the plot? (Sometimes writers forget about initial character motivations while getting lost in the writing process. This is the time to revisit that!)

Do you have a beginning, an inciting incident, building through the middle, and payoff at the end? (You can have much more than these, but these are very basic plot mechanics to look for.)

3. Save and Start a Second Draft

After reading through your manuscript and noting the things above, create a copy for your second draft and start working on your notes. It’s good to have a separate second copy in case you want to include something from the original draft later on or just want to compare where you story started/how it ended up.

Again, you’re not supposed to worry about line work at this point. Focus on bigger-picture story issues like plot mechanics, how scenes work/don’t work, plot holes, and your theme(s).

Reminder: there’s no timeline for getting these steps done. Work when you have the energy and take breaks when you don’t. Your manuscript will stay right where you save it.

4. Reread Your Work

When you’ve worked through your list of notes, make a copy of your manuscript and start Round 3. Reread your story and start a new list of bigger-picture notes as needed. This time, the list should be shorter or include new notes that you didn’t catch before. They may also include notes for new scenes you just added.

The point of this reread is to make sure that your manuscript still works. Your plot shouldn’t have any holes, it should flow smoothly, and it should be engaging.

Here’s a key concern for many writers: how do you edit your story without getting away from your original intentions?

Keep your eyes locked on why you write your original draft. If you make edits/scene removals or additions with that purpose or theme in mind, your story will stay on track. It may eventually look completely different than what you originally wrote (if that’s your editing journey), but the heart of it will remain the same.

Try posting your story’s purpose or theme on a sticky note attached to your monitor.

You could also write the theme in your document’s header so it appears on every page.

5. Save and Start a Fourth Draft

Yes, it’s time for another new copy that’s your official fourth draft.

Remember—you can still walk away and return to your work later! Burnout won’t result in the story you’ve been working so hard to create. Get some sleep, see some friends, enjoy your other hobbies. You’ll come back ready to go.

The fourth draft is another chance to read through your work and ensure that everything works. Your chapters should get your characters closer to your theme/purpose with each page. The scenes should flow, not repeat information, and keep you engaged.

When you have a small list of edits or none at all, it’s time to start line work.

The spell check feature of any word processing software is a lifesaver, but it’s also not perfect. You’re going to have sentence structures that spell check deems incorrect when it actually works for your writing style or character. You’ll have fake names you made up that spell check wants to change.

If you use spell check, proceed slowly. Read every sentence with a flagged issue to make sure it’s a good or bad suggestion.

You can double your line work by combing through it by yourself. Print your story and grab a highlighter or use the highlight feature on your computer. Note linework issues that you can fix with a quick edit when you get a chance, like:

Misspellings

Missing punctuation

Wrong punctuation marks

Missing words

Inconsistent capitalization or spelling

Formatting issues (spelling out numbers vs using numerals, etc.)

Using the wrong tense in some paragraphs or chapters

Inserting indents as needed

Extra spaces between paragraphs

6. Send Your Work to Beta Readers

Repeat the saving, making a copy, and editing as many times as you want. When you feel like you’ve got your strongest draft yet, you can send it to beta readers.

How you define beta readers depends on your specific situation. You may have a few writing friends who know the craft well and will read your work with a professional eye. You might have a family member or best friend who doesn’t know about the craft of writing but always reads your work.

There are also places like Reddit threads and Facebook groups where people volunteer as beta readers.

The primary reason to get fresh eyes on your work is to get notes from someone who hasn’t been working on the content for months or years.

Their advice might not always be usable, but it’s still an important part of editing. Your beta reader might suggest points where they lost interest because your pacing slows down or point out places where you described your protagonist as having long hair when they have short hair during the rest of the story.

You’ll know which suggestions are actionable and which aren’t based on who’s speaking and how it resonates with your story’s purpose. You’ll probably get better advice from other writers who have been through editing before, but that doesn’t mean their advice will always be correct.

Check in with your story’s purpose or theme before taking action on a beta reader’s notes.

When Should You Stop Editing?

One of the final battles during your editing experience will be recognizing when you can stop working on your manuscript.

There will always be moments where you could think of a new scene or a new way to rewrite a scene. That doesn’t mean you have to!

Ask yourself these questions to finish your editing when your story is strongest:

Question 1: Have I Worked Through the Most Essential Plot Mechanics?

A finished manuscript doesn’t need more structural work. But structural, I mean that you’ll be at peace because your manuscript:

Doesn’t have any plot holes

Addresses your theme/message from beginning to end

Showcases each character’s growth through plot developments

Has natural dialogue

Has introduced and resolved conflicts (with the exception of conflicts that will continue in a sequel or series)

Has no known typos or grammar issues

Question 2: Are My Edits Improvements or Are They Inconsequential?

You could spend a lifetime swapping character names, adjusting your world map, or revising how you describe locations. You might like your edits better, but they aren’t vital to your story’s plot or character development. If there’s no substantial improvement with your edits, you’re likely done with your manuscript.

-----

Editing can be tricky at first, but using steps like these will help you whack through the densest parts of the work. Take your time, give yourself space to rest, and you’ll create the story you’ve been working so hard to finish!

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

self editing tips (first pass)

you want your work to be awesome. i want your work to be awesome. i would love to help you make your work awesome. but sometimes, the first step is doing an initial pass over your draft before passing it off to """""professionals""""" like us. so here are some tips to get that party started...

print your book. you can print it out onto a bunch of sheets of paper and staple them together, or, if you don't mind spending $9 or so, you can get barnes and noble to print it into an actual novel for you! i highly recommend the latter. it helps you view your work as an actual book, not a mess of computer words.

set up the atmosphere. put on some nice ambient music, get yourself a nice coffee or tea or whatever drink you like, light a candle! make your editing workspace feel awesome.

don't change anything during your first pass. this is part of why i recommend printing it! i just want you to take notes, baby. highlight things in different colors if you want. jot down notes if you want. use transparent sticky notes, annotate onto the page, whatever your vibe is. but don't actually change anything right now.

compliment sandwich. after every editing session, write down one thing you think is working from what you read in that session, one thing you want to change or improve, and one more thing you're happy with.

keep a growth mindset, not a fixed mindset. this isn't a bad version that isn't up to your standards and is therefore hopeless. this is a moving part of your book's journey! this is step one. you can't get to step two without acknowledging the value of step one and thanking it for its time.

give yourself breaks to read, listen to music, or watch something with similar vibes to what you're going for. for me, this looks like reading books in the genre i'm writing in, watching shows with characters i really love, listening to music that fits the vibe, or reading poetry about the emotions relevant to my work.

log your progress. maybe write a checklist of every section/chapter so you can check parts off as you finish your first pass. this helps you feel productive, like you're really Doing Something even if you only edited six pages.

second pass tips coming soon! for now, happy writing, and please feel free to send us messages if you have any questions :)

#writing#writing tips#editing tips#self editing#indie author#writers of tumblr#editing block#editing ideas#writing advice#editing advice#self editing tips#story writing#novel editing#story editing#write it#novel writing#writeblr#creative writing#writers block#nanowrimo

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

the writing process is more than just writing

I saw this picture on Twitter today, and I laughed. I think it’s funny, and I think we all like playfully bullying ourselves with things like this.

But I also think way too many of us believe that the only acceptable part of the writing process is the actual writing. That’s...just not true.

There are sooooo many non-writing or writing-extra things that can be part of your writing process. Making playlists? Writing process. Creating aesthetics on Pinterest? Writing process. Talking about your book part of the writing process!

We all have a creative well that will run dry, a creative spark that will be snuffed out if we allow it. If we force it. You’ll force that if you don’t feed that creative energy, and that’s what you’re doing when you participate in all these non-writing pieces of the writing process.

You’re involved in the writing process anytime you engage in storytelling--that means reading books but it also means watching movies or TV and playing video games. Daydreaming! Daydreaming is an excellent way to feed your creative brain, and it IS part of the writing process. Please, writers, I’m begging you to stop forcing yourself out of daydreaming and into writing.

You need activities other than writing within your writing process if it’s going to be fun, successful, and especially if it’s going to be repeatable. If you bully yourself into finishing this novel, great, you’re done...and now you’ll hate writing the next one. Your poor brain!

The writing process is so much more than just writing, and you’ll be a better, happier, more productive writer if you don’t fight that.

326 notes

·

View notes

Text

Editing Tips for Beginning Editors

This is a guest post written by Adrian Harley.

Congratulations! If you’re reading this, I’m willing to bet you already have a lot of the skills you need to be an editor. Even among full-time professionals, a lot of editing skill comes from reading a ton—you get an “eye” for when a sentence just doesn’t look right. The more you read professionally edited work, the better you get at it. (Fanfiction is incredible, obviously. But fanfiction has its own quirks, and the grammar and punctuation can vary, so I’m not confident recommending it as a way to brush up your instinctive grasp of when a sentence “looks right.”)

The specifics of what you do as an editor can vary a lot depending on what you’re editing and who you’re editing for, so in this post, I’ll be covering some of the basic principles that I think will be helpful no matter what type of editing you do. Broadly, I’ll be going over language-related tips and profession-related tips.

Language

I won’t be going over the nuts and bolts of grammar here, as a zillion good guides to it already exist online. Grammar Girl is my go-to free resource, and a lot of grammar and punctuation questions can be easily answered online or in a style guide from your library. I looked up the rules for commas a LOT in my first years of editing, and I still have to double-check them sometimes. A lot of the fiddly details differ between guides (how to write a.m. and p.m.; serial comma), but the nuts and bolts of grammar and punctuation stay the same across guides.

Professionally, those fiddly details are a big chunk of editing. Do you write out numbers less than 20? Less than 10? Do you capitalize titles like “President” all the time or only in certain situations? There’s no one right answer, which is one of the many reasons there’s no “right guide” to editing. A style guide will decide many of these questions for you. If you pick up editing as a profession, your employer will most likely have a style guide in mind. You may want to pick one for yourself if you do freelance editing. That way, you won’t have to re-decide on every job, and if you get repeat clients, you’ll be sure their text is consistent across all their documents. A “series bible” for fiction works on similar principles.

Whether you’re looking at those fiddly details or at the big picture, one principle of editing is to never take anything for granted. Someone says there’s five ancient orbs needed to defeat the dragon? You’d better count the orbs. Make sure every proper noun in the story (names of people, places, things) is spelled the same every single time. This is the kind of thing you’ll get quizzed on if you ever apply for a professional editing gig. Every editing job I’ve ever applied to has an “editing test” of at least a page, and it usually has at least one of those errors (if not both).

Another major thing to watch out for is colloquialisms, especially ones that mean multiple things. A short list of common errors I see:

“Since” should only relate to the passage of time; it does not mean “because.”

“While,” again, should only refer to time—two things happening simultaneously. “But,” “although,” “whereas,” and others are good substitutes for the other sense.

“Due to” does not mean “because of,” it means “caused by” (and I’ve seen some editors argue to not even use it for “caused by” and to only use it for when something is owed to someone).

“If” will often need to be replaced with “whether.”

Obviously with dialogue, that’s a whole nother story, but be careful about these in narration, even with a colloquial narrative. They can introduce unintentional double meanings.

When you’re moving from basic accuracy to style, you’ll often need to “tighten up” the language. This might be something you’re used to doing in your own writing. This doesn’t mean all prose should be sparse! But as an editor, part of your job is making sure that every word is contributing something, no matter whether the sentence is flowery or stark. One exercise is to go through and see if you can cut one word from every sentence. Depending on what type of editing you do, you’ll have different “filler words” to look out for. My personal demon is “just,” so I always do a search for that when I’m revising my own work. In my day job, the word “provide” often signals a clunky phrase that could be condensed into a single, better verb (e.g., “provides assistance” vs. “helps”).

You’ll look for a lot as you edit, so don’t feel like you have to do it all at once. A simple search can make sure you’ve caught issues like “while” and “since.” Other issues are best solved in their own read-through. For me, I try to do a read-through specifically for passive voice. I often skip over passive voice on my all-purpose read because, well, the sentence makes sense, doesn’t it? So my eye simply doesn’t catch it if I’m not on the lookout. As you edit, you’ll figure out what process works best for you.

And to wrap up the language section—checklists are your friend! I used to have a post-it of all the things I knew I struggled with, and I’d systematically search the document for those trip-ups after I did my first read. You can customize your own checklist with whatever snags give you trouble.

Professionalism

A huge part of editing as a professional is in how you interact with other people. Your whole job is telling people they’re wrong, after all, and you often have no control over whether they’ll listen to you. Everything you can do to make the criticism easier for them helps!

My favorite “one weird trick” that my first boss taught me is to turn every criticism into a question. If you’re suggesting a significant revision, “How about…?” is one of my favorite leads. If you have no idea what’s going on, do your best to figure out what might be causing the issue, then form a question around that. “Are there missing words here?” is kinder and more useful than “Huh?”

Essentially, your role as an editor is to advocate for the reader. This “reader stand-in” role can help frame critique as well. Will the reader understand this? If you’re in one of the more-technical editing jobs, that question may be completely necessary. As an editor for scientific research, I’m often editing documents meant for people who know way more about the subject matter than I do. The framing of “the reader” is also a useful tool in your toolbox for fiction. You may be editing something that you are not the target audience for. Or, on the other end of the scale, you may know without question that you’re reading something incomprehensible. The polite device of “the reader” helps add a level of depersonalization to the critique.

Unsurprisingly, for editing, communication is key before you even start work. “Editing” covers a huge range of possibilities. Make sure you and the author are on the same page. Do they want a proofread—only correcting glaring errors? Do they want you to improve the phrasing of sentences? It can go all the way up to practically rewriting the thing, if you’re working at a corporation and the authors aren’t professionals. This conversation beforehand will let you know whether you should make “artistic” suggestions as you read, whether you need to stick with nuts and bolts, or something in between.

If the author says they only need a proofread and you discover the whole thing is terrible, that’s when some tactful emails come into play. Never start doing a higher-level edit unless you’ve talked about it with the author first. You have much better odds of an affirmative if they feel like they’re collaborating with you–that you’re both in it together to make the best document possible. As far as the tactful emails go, be kind and be specific. If you have examples of what you’d like to correct, throw those in. It helps the author know what to expect and make an informed decision.

And sometimes the author says no, and that’s okay! You must wash your hands of it. It’s not your name on the thing, and if you don’t put it in your resume, it never will be (fresh out of college, I worked on a couple truly awful novels that nobody will ever know I worked on). Perfectionism is HARD to overcome, I know, but accepting the errors gets easier with practice.

And finally, if you’re still wondering, “Am I cut out to be an editor?” I would recommend the words of Neil Gaiman. In his excellent “Make Good Art” speech, he says that as a freelance artist, you need to do good work, do it on time, and be pleasant to work with. And then, he adds, “You don’t even need all three! Two out of three is fine.”I recommend the whole thing if you ever want to battle imposter syndrome, because the same tenets apply to editing. At least I think they do. You don’t need to be the perfect editor—nobody is. But I guarantee that you have most of what you need already, and I hope this has helped.

Biography

Adrian Harley, one of Duck Prints Press’s editors, has been a full-time professional editor of scientific research for 10 years. Their freelance and ad-hoc editing has run the gamut from books to blog posts to family members’ cover letters. They’ve been published in Duck Prints Press’ And Seek (Not) to Alter Me and the forthcoming She Wears the Midnight Crown, as well as OFIC Magazine.

Want to learn more?

Beware the Weasel Word has information and resources for “tightening up” language.

How to Ask for Feedback on Your Writing talks more about how, from a writer point of view, to help your editor understand what type(s) of editing you’re looking for.

Giving Quality, Motivating Feedback focuses on exactly what it says on the tin: how to give a writer feedback they’ll listen to.

What is an Alpha Reader? talks about what role alpha reader editors play and how to work with one.

219 notes

·

View notes

Text

Be your own editor/critic. Sympathetic but merciless!

– Joyce Carol Oates

#fiction#fiction writing#editing tips#editing advice#joyce carol oates#quotes#kcawf original#writeblr

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

tips for editing novels i wrote instead of editing

these are mainly targeted to people who find it hard to focus on editing (like yours truly) but really helps for anyone.

work section by section. i started doing this and it wasn't working because i kept reading on to the section after instead of focusing on editing the one section so what i did is copy paste the section (each should be no more than like 1000 words) onto another document and work on it there. read it over and over again until it sounds the way you want it to sound that copy paste it onto the other document and move on to the next section.

sit somewhere quiet. absolutely quiet.

no music.

turn off the wifi on your phone and on your laptop.

to get the emotion right in a scene, listen to music that embodies it. can't catch me now (olivia rodrigo) and east of eden (zella day) are what i'm listening to right now. of course, i can't write and listen to music at the same time because that's the kind of person i am but before you start writing, listen to the music and really get in the feels because emotion is what drives a story forward more than plot

i actually saw an author say this, i can't remember who, but it's good to have a song that evokes emotion so you can write the emotion properly

THESAURUSES. lifesavers. i can't come up with the perfect word to describe something because i have poor memory but the thesaurus always remembers (am i even spelling it right?)

drink water. (now. stand up. if you don't istg i'll find you.)

change the cliches. don't say it was a dark and stormy night. say it was a starless night that smothered even the smallest lamp lit in the little window of a small store at the edge of the abandoned town.

don't tell me what happened, tell me how it felt. it was not cold. her nose stung and her fingernails turned blue, she stamped her feet to keep warm, she shivered despite herself, her teeth chattering.

i think the trick is to search for every time you used the word 'was' and change it to a feeling

read aloud. do impressions. make your annoying character sound like your social studies teacher from 11th grade. have fun with it. just make sure the dialogue doesn't sound stiff and make sure the sentences flow well.

as a rule, shorter sentences flow better and are easier to understand

add more internal monologue, have your character try to reason things in their heads, don't have them just observe what's happening.

this is something i struggle with but if you have a mystery with a grand reveal in the end, keep track of what your readers know and don't know. reveal tiny clues that only fit when you finally see the full picture. be as evil with it as you want.

for motivation, reread your favorite scene (mine is the mc and love interest being adorable)

also, imagine the book being published. who would you dedicate it to? how many people would make tumblr posts analyzing it, how many people would make memes, who would the fandom ship?

finally, unrelated to editing, but if you must kill off characters, don't do it just because you want something dramatic and you need the plot to move forward, only do it for two reasons:

a) it completes the character's arc (i.e. they were afraid of death but when someone they truly loved was in danger they jumped in front of a bullet to save them)

b) they're going to come back to life later as a metaphor for phoenixes rising or something

personally, my favorite thing to do is to leave the death ambiguous. no one will know if the character really died or not (not even me)

#editing#advice#writeblr#creative writing#writing community#writers of tumblr#writing advice#editing advice#writing tips#social studies teacher from 11th grade is the most traumatic human being let me tell you --

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Source.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

A piece of advice often given to writers is "just write; you can always edit later."

It's good advice, but with a caveat: you can't always edit later. You have to know how to edit.

Editing is a different skill from writing. Only recently have I managed to edit my own writing; up until the last few months it was either write it correctly the first time around or get a beta to edit it for me/tell me what to fix.

And as I'm editing/rewriting a scene right now, I wanted to share with you some tips I've picked up from practice and other resources.

A. STYLE

- Run grammar and spell check. If you haven't already. Personally, I like to look these things up as I write, but I suppose some of you might prefer to write your stream of consciousness first and edit later. Whatever works. (Just please run your check at some point. It's crucial.)

- Read out loud. You can find from missing commas to typos to stilted dialogue if you check how your writing rolls off the tongue.

- Count your adjectives, your adverbs and your -ings. Not to keep score, obviously; but these are parts of speech that are best used in moderation. If there are three adverbs in one line of text, you might need to eliminate one or two.

- Use your thesaurus. Again, in moderation. Look for oft-repeated or very trite words and replace them. If there are no working synonyms and you're still being too repetitive, consider a full rephrase.

B. CONTENT

- Be prepared to lose content. You might be forced to edit out a turn of phrase you like or a background detail that's not necessary for your story. Make your peace with it. Do try to work it in if you like it, but don't do it at the expense of your story. This is the cornerstone of editing.

- Don't hard delete. Keep your previous drafts. They may come in handy.

- Apply the writing tips you're given. For instance, "show, don't tell". Look for instances of telling that could be improved by showing, and rework. (Not going to get into an exhausting list of these.)

- Check the purpose of the scene. Every scene you write has a purpose, be it plot-wise, characterization-wise, setting up the scene for something or whatever else - otherwise you wouldn't be writing it. Read the scene again: does it do what you want it to do? If not, focus on your goal: what would be another way to achieve it? And work from there.

- Count your dialogue, introspection, and descriptions. This depends on your style too, but sometimes the problem with a scene may be that it's too heavy on one or the other. Often, I may not be in my best writing shape, but a dialogue pops in my head; I write it down to use as my guide, then when it's editing time, I add the details around it.

- Reread your previous scenes. It will help you get more in touch with your story and style and perhaps give you ideas such as what you can address that you haven't already.

- Mimic your favourite writers. Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery. If something doesn't work for you, think: How would X write it? What would they tell me to change if they read it? Don't worry, you won't get nearly close enough for it to be a problem. 😋

- Be prepared to rewrite. Sometimes editing just doesn't cut it; you have to rewrite from scratch. Paste your previous draft where you can't see it and start again.

C. GENERAL

- Take some distance. Look at your writing again tomorrow, or next week, if you can afford to. I know when my writing is fresh I am too attached to it. A week later, I am much more likely to edit out a sentence that doesn't work even if I really like the fancy verb I chose to use in it.

- Be aware of time and circumstance. Not all days are good for editing. You may be too tired one evening; you may need another cup of coffee one morning; you may be too aware of your pending chores one day. Don't force it; give it another shot when you're in a better state of mind.

- Write down your comments. Too often, we feel something is not good but we don't know why. Write down your comments as if you'd explain to someone what you don't like about it, then come back to it.

- Get a beta. Boy, do I know it's hard! But a good beta is a (all right, figurative) life-saver. Ask around, or ask a friend. I'm not saying don't post unless you get a beta, but I'm telling you it's not a shame to ask for help. I literally never post without at least getting someone to read my work first, even if all they are equipped to say is "It was good, I liked it."

- Beta for others. It's easier to spot what needs fixing in a piece that's not your own. You don't have to be super experienced, catch every single mistake, or produce a professional result; just read and comment on what feels off, explaining why (so that it's easier for the writer to know how to fix it). It's good practice, and you help someone.

I hope this will be of use to some of you! Happy editing!

288 notes

·

View notes

Text

I can't just keep adding subplots

... or can i?

#writer#writer life#writing#writing stuff#writing a book#writing problems#editing#book editing#editing tips#editing advice#subplot#romantic subplot#new author#booktok

256 notes

·

View notes

Text

#writers of tumblr#writing advice#editing advice#editing tips#writeblr#writing community#quotes#zadie smith

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Get some distance before you proofread

Never begin proofreading immediately after a first draft or edit. Your brain will read what it's expecting, not what's actually there.

Take a break, and read something from another genre as a palate cleanser. You'll be more likely to spot errors if you get some distance.

#writers#creative writing#writing#writing community#writers of tumblr#creative writers#writing inspiration#writerblr#writeblr#writing tips#writblr#editing#proofreading#editing advice#editing tips#quick tips for writers#writing quick tips#creative writing tips#advice for authors#writing advice#advice for writers#writers corner

774 notes

·

View notes

Note

I want to be an editor someday! What are the most important qualities or skills you think an editor can have? Both from an editor perspective and an author perspective?

Hi Anon!

This is a great question that has lots of answers because it really depends on the kind of editing you do and what the expectations are. But in general, I think that having an understanding of authorial intent and voice is super important. Authors make choices in their art, and any editor who believes rules supersede those artistic choices in every situation possible is not taking into account that writing is art.

There are copyeditors (or copy editors, I know some of you like seeing this term open) who hew strictly to their style guide of choice, the dictionary (Merriam-Webster Collegiate is the gold standard in trade publishing), and/or the house style guide, even when the author demonstrates a clear preference for something that's contra the guides or the dictionary. Sometimes it's for a very good reason. For example, I know that "accouterment" is the American spelling and therefore the "correct" spelling in the US, but you can pry "accoutrement" from my bare hands only after I am dead. Sometimes the author simply does not know about the rule, and that's where your discretion comes in when writing a global query.

Hand in hand with understanding authorial intent and voice is the ability to query without being harsh. No one likes having a mean editor. It's tempting to snark or fuss at an author, especially when passages are egregious, but a gentle correction with the right tone of voice works much, much better than a comment that will result in your author thinking you hate them. Being a mean editor (I'm sorry, "brutally honest" if you're a man) is not a badge of honor. I'll say that again: Being a mean editor is not a badge of honor. Editors are there to help clarify and shape a document, all under the aegis of the author's vision. They are not there to cackle maniacally and go on power trips. It's a skill to write queries and letters with gentle but direct language and provide examples where they are needed, and it's something that's only developed over time.

What do I mean by gentle but direct language? Well, that's hard to define as well; authors take feedback in so many different ways, so what may seem gentle to you may not feel gentle to the author. As an author, I have received edit letters that made me spiral for two months. My editor was not mean. She was complimentary. It's just that she asked a lot of questions and I needed to break my manuscript apart to address them in the scope I think they needed to be addressed in, and then I ran into a block, and thus, a spiral ensued. And that's for a letter that was short and kind! Her language was great, though.

Overall, I think that language such as "Echo here intentional?" or "AU: I noticed that this chapter and the previous seem to be out of sync with the rest of the timeline. OK, or should that be changed?" and comments in that tenor are professional and will not be met with accusations of being mean. This goes for developmental edit letters too; you have to find the tone that suits you as an editor as you deliver news that amounts to "scrap the following and rebuild," which no one wants to hear even when we say we want to hear it! No, we want to have written it perfectly on the first try.

And lastly--this one may feel the most controversial, but it isn't if you're an editor, and is if you aren't--when you're on a job, take your sentimentality out of your editing. You'll definitely find manuscripts or papers or whatever you're editing that you're a fan of, and when that happens, it's really wonderful. The jobs go by so much quicker when you're enjoying the material. But you still have to be able to look at a work as objectively as you can and analyze it without regard to your personal feelings. People have asked me how I feel about things I've edited when I was editing them, and the real truth is, aside from a few manuscripts I really adored (but still took the magnifying glass to), I don't have particular attachments to them. I don't have opinions on them. It's work, and it's a sign of respect for your profession and your author that you give them your best, regardless of your feelings for the manuscript.

I know, I know, it sounds cruel. But it's also one of those things where you don't want to be overly harsh to an author because you really, really don't like the way they write, or miss things because you were so caught up in the book that you just could not stop reading it. In those cases, when you send the manuscript back to the author, you can include a little note about how much you loved it, how much you're looking forward to seeing it on the shelf or on your device, etc. There are exceptions, of course, and I try to sniff those out before I accept manuscripts so that I don't read something that hits all my triggers. And that's the last-last piece of advice I'll give on becoming a good editor. Learn what your boundaries are and how to say no. Sometimes, it feels like you can't say no because you need the cash or you want desperately to get word of mouth out, but editing is taxing on the mind and body and the only one who suffers the consequences of that work is you.

Hope that answered your question!

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

I'm on a bit of a plot block

Any tips?

Oh boy, plotting. Lemme just--

--right, let's do this.

SO, YOU'VE LOST THE PLOT

The solution to this all too common problem varies from writer to writer and usually depends on the exact issue you're having, but here's a few things I usually do.

Re-read all the plot you've got so far

It sounds obvious and you've probably already done it, but sometimes it's as simple as re-reading everything to get your flow back!

Figure out what you want from the plot

What's missing so far? Are there any characters being left behind? Have you opened a plot thread that hasn't been mentioned in a while? Is there a piece of character development you really really want to happen? Taking some time to think about what you have and what you're missing is important!

Skip that bit

You heard me. Figure out the next bit of plot you want to happen, skip to that bit. Come back to bridge the gap later!

Start over

I know I know, you put all this time into plotting and I'm telling you to scrap it. Don't scrap it! But just start writing the plot again from scratch and figure it out from there. Sometimes just the process of rewriting the same thing will give you a better perspective on where you're going! And sometimes you'll find the reason you can't get past the block is because something earlier in the plot isn't working, and this'll give you a chance to reshuffle and fix it!

Try a new medium

This is a lil bonus option I found recently works for me: just,,,, write somewhere else. New location, new medium, new program. I write all my plotting by hand! It helps me to have to write slower and to be able to plot somewhere that isn't the same place I write and spend my days (at my PC)

Hope this helps! It's hard to give any solid advice with something so wide, but these are some good starting points if you're not sure what's going wrong <3

#writing advice#author advice#writeblr#authorblr#novel planning#writing process#authors of tumblr#answered#mine#writing#editing advice#editing process#plotting advice#plotting process#anonymous

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

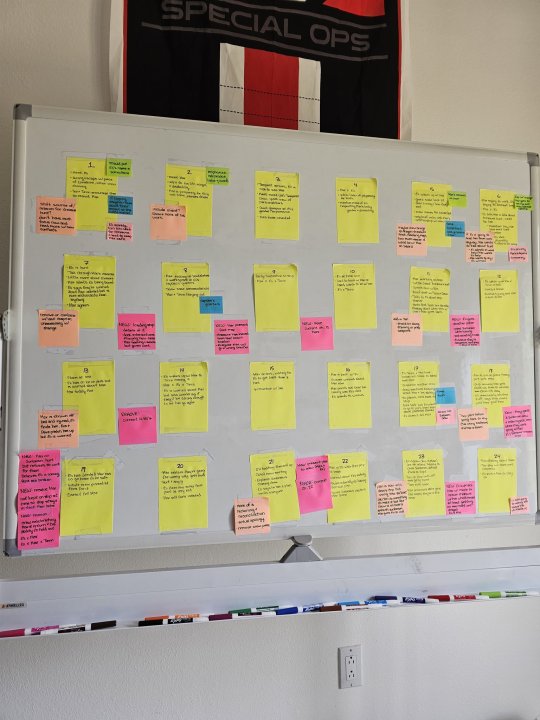

an editor’s editing process...

...is a little anal, and probably a little chaotic, but it’s very effective!

Here's how I plan and prep for my big edits/rewrites. The general idea is a visual display of the whole novel, chapter by chapter, with color-coded Post-it’s that decrease in size as we get from big pieces of content down to smaller details.

I have my giant whiteboard (isn’t she beautiful?), and I map out each chapter with the yellow larger rectangles. Effectively these are a super simple backward outline with just a quick bulleted list of the content in every chapter.

The orange-y squares are for bigger content or structure changes. If I’m editing the content of a chapter, I use one of these.

The smallest Post-it’s are for the details, one for worldbuilding, one for character details, and another for focus points within the chapter.

The final piece is those bright pink squares that show me where I’m going to add or remove a chapter and a quick description of what’s going into that chapter.

And of course, because this is me, I have a key nearby so I don’t forget which color or Post-it is what.

Especially with my neurodivergent brain, I find that a visual aspect added to my editing process is a game changer. Most people might have some pages of notes, might have it all in their mind, and then they sit down to edit. But I can’t sit down with a book I know by heart, all these edits in mind, and just...do it.

First of all, that’s boring. ADHD brains don’t do boring. And I don’t really want to get bored with my book!

Second, I’ll definitely lose track of everything I intend to do/add/change/remove. It’ll end up costing me more time in revisions when I need to go through another round of the things I forgot, and that’s assuming these things aren’t connected because that’s a whole different mess!

Third, that just leaves me with no space to think things through, to test things out and move them around, to change my mind on the fly.

This chaotic, beautiful board changes all that!

When I edit for clients, I often walk them through the process of taking in edits and organizing the work needed. This sort of visual can be extremely helpful, and you could make this work in a notebook with post-its!

Everyone's process is going to be different, but if you find edits really painful, anxiety-inducing, difficult—consider adding a visual step. It might make all the difference.

Now...go forth and revise!

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

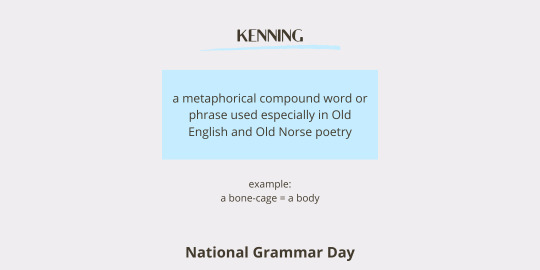

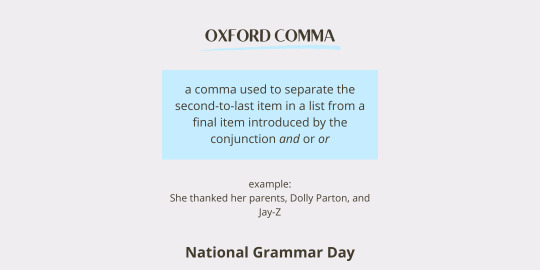

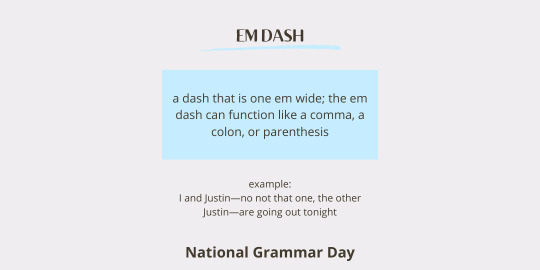

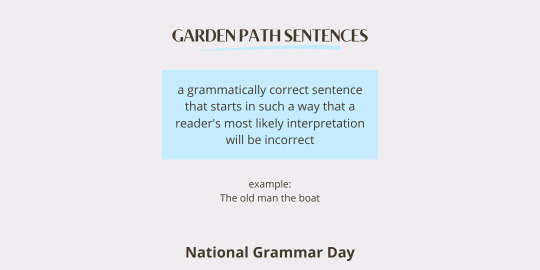

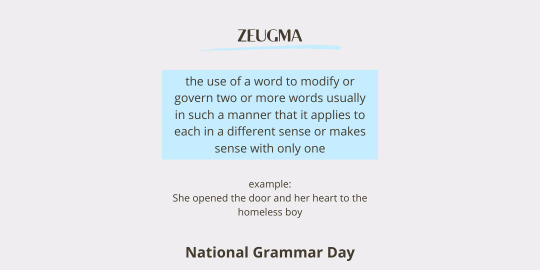

Celebrate National Grammar Day with 6 of Our Favorite Grammar Quirks!

What are your favorite things in grammar?

Here are some of ours!

Interrobang: a punction mark ‽ designed for use especially at the end of an exclamatory rhetorical question.

Example: You call that a cat‽

Kenning: a metaphorical compound word or phrase used especially in Old English and Old Norse poetry.

Example: a bone-cage = a body.

Oxford Comma: a comma used to separate the second-to-last item in a list from a final item introduced by the conjunction and or or

Example: She thanked her parents, Dolly Parton, and Jay-Z.

Em Dash: a dash that is one em wide; the em dash can function like a comma, a colon, or a parenthesis

Example: I and Justin—no not that one, the other Justin—are going out tonight.

Garden Path Sentences: a grammatically correct sentence that starts in such a way that a reader’s most likely interpretation will be incorrect

Example: The old man the boat.

Zeugma: the use of a word to modify or govern two or more words, usually in such a manner that it applies to each in a different sense or makes sense with only one

Example: She opened the door and her heart to the homeless boy.

*

Comment and tell us YOUR favorite grammar quirk in English (or some other language, why not!) We'd love to hear about it!

Post contributors: theirprofoundbond, boneturtle, unforth, owlish, and shadaras.

Who we are: Duck Prints Press LLC is an independent publisher based in New York State. Our founding vision is to help fanfiction authors navigate the complex process of bringing their original works from first draft to print, culminating in publishing their work under our imprint. We are particularly dedicated to working with queer authors and publishing stories featuring characters from across the LGBTQIA+ spectrum. Love what we do? Want to make sure you don’t miss the announcement for future giveaways? Sign up for our monthly newsletter and get previews, behind-the-scenes information, coupons, and more!

#duck prints press#weekly blog feature#national grammar day#grammar#editing advice#english#english is weird

57 notes

·

View notes