#president truman

Note

Just saw Oppenheimer and I was a bit disappointed with how they portrayed Truman. He came across pretty poorly IMO. It was only one scene but I wondered what you thought.

I understand your disappointment and it certainly wasn't a very in-depth portrayal of Truman, but according to the book that the movie was largely based on -- American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO) -- the meeting that Oppenheimer had with President Truman went down pretty much as depicted in the film.

As Bird and Sherwin write in American Prometheus:

(O)n October 25, 1945, Oppenheimer was ushered into the Oval Office. President Truman was naturally curious to meet the celebrated physicist, whom he knew by reputation to be an eloquent and charismatic figure. After being introduced by Secretary [of War Robert P.] Patterson, the only other individual in the room, the three men sat down. By one account, Truman opened the conversation by asking for Oppenheimer's help in getting Congress to pass the May-Johnson bill, giving the Army permanent control over atomic energy. "The first thing is to define the national problem," Truman said, "then the international." Oppenheimer let an uncomfortably long silence pass and then said, haltingly, "Perhaps it would be best first to define the international problem." He meant, of course, that the first imperative was to stop the spread of these weapons by placing international controls over all atomic technology. At one point in their conversation, Truman suddenly asked him to guess when the Russians would develop their own atomic bomb. When Oppie replied that he did not know, Truman confidently said he knew the answer: "Never."

For Oppenheimer, such foolishness was proof of Truman's limitations. The "incomprehension it showed just knocked the heart out of him," recalled Willie Higinbotham. As for Truman, a man who compensated for his insecurities with calculated displays of decisiveness, Oppenheimer seemed maddeningly tentative, obscure -- and cheerless. Finally, sensing that the President was not comprehending the deadly urgency of his message, Oppenheimer nervously wrung his hands and uttered another of those regrettable remarks that he characteristically made under pressure. "Mr. President," he said quietly, "I feel I have blood on my hands."

The comment angered Truman. He later informed David Lilienthal, "I told him the blood was on my hands -- to let me worry about that." But over the years, Truman embellished the story. By one account, he replied, "Never mind, it'll all come out in the wash." In yet another version, he pulled his handkerchief from his breast pocket and offered it to Oppenheimer, saying, "Well, here, would you like to wipe your hands?"

An awkward silence followed this exchange, and then Truman stood up to signal that the meeting was over. The two men shook hands, and Truman reportedly said, "Don't worry, we're going to work something out, and you're going to help us."

Afterwards, the President was heard to mutter, "Blood on his hands, dammit, he hasn't half as much blood on his hands as I have. You just don't go around bellyaching about it." He later told [Secretary of State] Dean Acheson, "I don't want to see that son-of-a-bitch in this office ever again." Even in May 1946, the encounter still vivid in his mind, he wrote Acheson and described Oppenheimer as a "cry-baby scientist" who had come to "my office some five or six months ago and spent most of his time wringing his hands and telling me they had blood on them because of the discovery of atomic energy."

#Oppenheimer#History#Oppenheimer Film#J. Robert Oppenheimer#Harry S. Truman#President Truman#Truman Administration#Atomic Bomb#Manhattan Project#Trinity Test#Oppenheimer Movie#Christopher Nolan#Cillian Murphy#Gary Oldman#American Prometheus#American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer#Kai Bird#Martin J. Sherwin#Nuclear Weapons#World War II

77 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Years after the fact, President Harry Truman explained his controversial firing of General Douglas MacArthur in 1951:

“I fired him because he wouldn’t respect the authority of the president … I didn’t fire him because he was a dumb son of a bitch, although he was, but that’s not against the law for generals. It if was, half to three-quarters of them would be in jail...

“I’m afraid he wasn’t right in the head … He didn’t have anybody on his staff that wasn’t an ass kisser. He just wouldn’t let anybody near him who wouldn’t kiss his ass. So… there were times when he was… I think out of his head and didn’t know what he was doing...

“He was wearing those damn sunglasses of his and a shirt that was unbuttoned and a cap that had a lot of hardware. I never did understand… an old man like that and a five-star general to boot, why he went around dressed up like a nineteen-year-old second lieutenant.”

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Like countless moviegoers around the world, I’m a major fan of Christopher Nolan’s “Oppenheimer.” But like many of those who saw it, I wasn’t alone in having qualifications about the last part of the movie. For me, the first two hours of “Oppenheimer” were electrifying. I felt the kind of full-scale mind/soul immersion that’s the definition of what we look for when we go to the movies. But in the last hour, I experienced a certain falling-off quality. I was still involved, but less involved. As the film kept returning to the 1954 hearing that resulted in Oppenheimer losing his security clearance, with Oppenheimer in the hot seat being hectored by a team of interrogators led by Jason Clarke’s special counsel to the AEC, I thought, “Why are we still at this damn hearing?” I asked because I didn’t know.

Now I do. A month or so after “Oppenheimer” opened, I went back and saw it again, and this time my qualifications evaporated. I was just as electrified as I’d been by the first two hours — only now that sensation didn’t end. The feeling of immersion lasted all three hours, right to the final shot. I’m a bit embarrassed to say this, since it means admitting that I didn’t get the film right the first time; as much as I raved about it in my Variety review, I would now rewrite the last part of that piece. But I’m even more fascinated by why I missed a crucial element of the movie.

“Oppenheimer” presents its title character as a totemic figure, a daring, mysterious, endlessly complicated renaissance genius who rose to his moment by envisioning and overseeing the creation of the atomic bomb. Cillian Murphy, in his mesmerizing performance, endows Oppenheimer with an all-knowing aristocratic dandy swagger. He makes him a singularly charismatic figure, a wizardly idealist who conjures up an awesome power and then grapples with the consequences of his actions. And since it feels as if Oppenheimer, at that hearing, is being persecuted (to a large extent for his earlier Communist ties), it was hard to watch it without feeling like I was on his side.

The movie, however, is not on his side. Not really. In the last hour, it’s deeply critical of Oppenheimer — as critical, I would say, as any major Hollywood biopic has ever been of its subject. And this is the road I didn’t fully let myself travel down the first time I saw “Oppenheimer.” The last hour was trying to me because I was fighting what the movie was.

I can say, with some surprise, that the final hour of “Oppenheimer” is now my favorite part of the movie. It’s the most morally dramatic and hypnotic — the true inquiry into who Oppenheimer was, and why he’s a hero who will always have an oversize asterisk next to his name.

The first time out, I thought I was watching a drama about the creation of the A-bomb. But as captivating as all that is — the science-lab frenzy, the race against the clock, the thorny politics of life in the makeshift city that was set up in the Los Alamos desert — the process by which Oppenheimer and his fellow brainiacs transformed nuclear fission into a weapon capable of delivering a nuclear apocalypse is not exactly the stuff of spoiler alerts. They gathered; they devoted themselves; they wondered if they were going to set the global atmosphere on fire; they triumphed.

Since “Oppenheimer” is a movie with a built-in big bang, I spent a lot of that first viewing anticipating what the Trinity Test would look and feel like. I still think it’s the one disappointing aspect of the film. Nolan fragments the bomb detonation (glaring light, rising hellfire), and in doing so he somehow fails to channel its viscerally terrifying and unprecedented largeness. That kind of threw me off.

Was the building of the atomic bomb justified? “Oppenheimer” says that it absolutely was. The Nazis were working on their own bomb, and Oppenheimer, who was Jewish, very much saw his mission as an attempt to save civilization by winning a weapons race that, had the Nazis won it, might have resulted in a level of devastation beyond the unthinkable.

But was the dropping of the atomic bomb justified? Given that the Nazis had been defeated before the decision was made (by President Truman) to drop the weapon on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, a powerful case could be made that it was not. Should Nolan have depicted the effects of the bomb on the Japanese, as Spike Lee suggested this week? I think that would have made “Oppenheimer” a very different movie, and not necessarily a better one. I’m not here to rehash that debate, but I’ll point out that Nolan’s film features Oppenheimer, speaking to a roomful of his Manhattan Project colleagues, cutting to a kind of cosmic justification for dropping the bomb. He says, in essence, that it will act as an inoculation, forever scaring off the human race from using the bomb by demonstrating its deathly horror.

Perhaps he was right. But this was still Oppenheimer’s Faustian bargain. He convinced himself that dropping the bomb was justified, maybe even necessary, but in doing so he was also acting out of an elaborate and convoluted self-interest. On some level he’d invented a new toy and desperately wanted to use it. Though it wasn’t his decision to use it, he distanced himself from the horror of that decision.

The rest of the movie is about how the horror comes crawling back. I certainly saw elements of that the first time. But I what I missed, in my kneejerk-old-school-liberal way, is that the 1954 hearing runs on and on not because the film is trying to demonstrate that Oppenheimer was “persecuted.” As much as the Communist associations he had in the ’30s come into play, the point is not to depict the hearing as a McCarthyite smear (even though, in fact, it kind of was).

No, the startling thing about the last hour of “Oppenheimer” is that it features two characters who seem to exist almost entirely to prosecute and torment our hero, and in both cases what they say about him is right. “Oppenheimer” shows us how J. Robert Oppenheimer was not so much a victim of history, or of an oppressive U.S. government, as he was a defensive narcissist crusader who spent his final years using the trigger of his guilt to cover himself in a kind of grand delusion.

Robert Downey Jr.’s performance as Lewis Strauss, the former head of the AEC who becomes Oppenheimer’s antagonist, is a stupendous outpouring of extemporaneous verbal energy (the actor is even more commanding without his irony than he is with it). But because Strauss is the person who stabbed Oppenheimer in the back, I assumed, the first time I saw the movie, that Nolan figured he needed some sort of villain, and that the virulent, hawkish Strauss was it. Strauss certainly had petty personal motives; the film returns several times to the Congressional hearing in which Oppenheimer publicly humiliated him with a flippant comment about radioisotopes. Yet the reason that Strauss, in certain ways, comes close to dominating the film’s last hour isn’t simply because we’re watching a bureaucrat take his vengeance. It’s because Strauss is the one who understands, and articulates, a crucial element of the film’s verdict on Oppenheimer: that he was a brilliant and self-glorifying celebrity who forged a mythology around himself, one that extended into his very crusade against the weapon he’d created.

Oppenheimer was the scientist who let the nuclear genie out of the bottle, but after the war he devoted his life to essentially saying, “Let’s try to put it back in.” Never realizing that this was hypocritical and unreal. In public, he’d mocked Strauss, and it was Strauss’s sleazy double dealing that was on trial during his own 1959 Senate confirmation hearing for Secretary of Commerce — the other hearing that’s featured in the movie.

But the reason that Strauss is in the movie, and the reason Downey should win the Oscar for best supporting actor for his performance, is the fantastic fervor with which he rakes Oppenheimer over the coals. Just because Strauss is rather scurrilous doesn’t mean that he’s wrong; he’s the one who has Oppenheimer’s number. And so does Jason Clarke’s Roger Robb, the AEC attorney who, in one of the film’s most cathartic moments, gives a speech in the 1954 hearing that excoriates Oppenheimer for the hypocrisy of his position on the hydrogen bomb: his denunciation of it as a monstrously overscaled weapon — but talk about the wrong messenger! Oppenheimer’s A-bomb was already an obscenely overscaled monster.

Christopher Nolan, in that inquiring last hour, has written all this into the movie, not because he wants to damn J. Robert Oppenheimer but because he wants to take the full measure of a 20th-century visionary who charged into the creation of the atomic bomb as if it were the science project of a lifetime — which it was — but had the luxury of not fully thinking through the implications of his actions. By the time he thought them through, he’d turned his criticism of America’s nuclear policy into a grandly repressed apology. He used the nuclear debate, and even his own martyrdom, to justify himself. But the way the movie portrays this doesn’t make it an attack on Oppenheimer. It makes “Oppenheimer” a piece of history that’s also a human exploration of the most exhilarating honesty.'

#Oppenheimer#Christopher Nolan#Lewis Strauss#Robert Downey Jr.#Oscars#Cillian Murphy#Trinity test#President Truman#Jason Clarke#Roger Robb

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

I will never get over Harry Truman saying “It’s not the pope I’m afraid of, it’s the pop.” Regarding JFK becoming president 💀 Joe Sr was truly the devil lmao. Like imagine the man who dropped bombs on a country saying this about you? 😭

Omfg!!! 😭😭😭😭

Joe Sr was never beating his reputation

#anon#ask#answered#john f kennedy#jfk#joe kennedy sr#harry truman#president truman#kennedy family#the kennedys

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just finished reading the part of David McCullough’s biography on Truman about the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and there is no part of me that should be acting this introspective at this hour. I’m sitting in bed looking at the sky asking the REAL questions right now.

#history#america#president#millard fillmore#american history#presidents#president truman#harry truman#world war 2#there is something wrong with me

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alignment chart meme, but it's Barbenheimer <3

(Second is just a very random example. It's super inaccurate but if you watch Oppenheimer, you'd get why random characters like Josh and Rodrick are there ;) I haven't watched the Barbie movie yet tho)

#barbenheimer#barbie#oppenheimer#alignment chart#rodrick#wimpy kid#mr robot#iron man#mcu#marvel#dc#harley quinn#suicide squad#juno#the notebook#president truman#albert einstein#peaky blinders#tony stark#drake and josh#josh peck#elliot alderson#alignment#tommy shelby

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

can't get over when Gary Oldman my long time crush since I was like 10 appeared on that scene in Oppenheimer and the battle of gaze and anger and annoyance and displeasure between him and Cillian Murphy was an absolute perfection!

THE PEAK OF CINEMA, I daresay!

I was holding my breath for who knows how long and I wanted to scream all of my lungs out inside the theater but I kept it in. The agony and the excitement and the joy in seeing the talent these two possess. The power they hold in me. Gosh, I love them so much.

To my long time crush, Gary Oldman

And to my new, Cillian Murphy

(Out of 38 middle-aged people I collect as my ideal significant other) *I'm a fangirl for years lol

#oppenheimer#gary oldman#cillian murphy#that one scene#president truman#versus#j robert oppenheimer#the peak of cinema

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reading Truman’s letters to his wife and I saw something interesting

I sit here in this old house and work on foreign affairs, read reports, and work on speeches-all while listening to the ghosts walk up and down the hallway and even right in here in the study. The floors pop and the drapes move back and forth-I can just imagine old Andy and Teddy having an argument over Franklin. Or James Buchanan and Franklin Pierce deciding which was the more useless to the country. And when Millard Fillmore and Chester Arthur join in for place and show the din is almost unbearable.

source: Dear Bess: the Letters from Harry to Bess Truman, pg 515-16(letter date: June 12, 1945)

I would totally watch a show or read a story that’s just the ghosts of dead presidents haunting the White House, it could be pretty funny.

#history#us history#president truman#harry s truman#bold of him to assume that pierce and buchanan would acknowledge their uselessness#i can imagine the ghost of woodrow wilson scolding truman for desegregation#like 'are you an idiot? you can't desegregate the military! you'll destroy whatever chance you had at reelection!#and then being endlessly surprised when truman won the 1948 election

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

• President Harry Truman | media and editorial archive

The Mossadegh Project

#harry truman#truman#president truman#us president#eisenhower#dwight d eisenhower#us history#corruption#letter to the editor#us elections#us politics#democrats#democratic party#syracuse#1950s

1 note

·

View note

Note

Watched “Oppenheimer” last night, and I keep thinking about the scene with Gary Oldman as Truman. While I absolutely believe that Truman would have claimed all the credit & blame of dropping the bombs for himself, and also that Truman would have called Oppenheimer a cry baby and an s.o.b., I am struggling to think of Truman as being so naive that he thought that Russia would “never” develop their own bomb. I checked the reference — Ray Monk’s “Robert Oppenheimer” (2013) is the source for the scene, but I can’t get at his sources to see what he’s drawing from. McCullough’s “Truman” corroborates the cry baby comment and the blood-on-my-hands but not the “never” quote.

Do you have anything to hand about Truman’s belief in the Russian’s ability to build the bomb? How could anyone think that the Russians would “never” create a bomb?

In American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO), which I believe was one of Christopher Nolan's major inspirations for the film, Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin go into detail about that meeting between Truman and Oppenheimer and the scene in the film takes almost word-for-word what is written in the book. Truman is actually quoted in the book as saying "Never" after asking Oppenheimer when he thought the Russians would develop their own atomic bomb and not getting a response.

The sources that Bird and Sherwin list for that meeting and the "Never" comment are Nuel Pharr Davis in the 1968 book Lawrence and Oppenheimer, and Murray Kempton, who wrote about the meeting and the comment in the December 1983 issue of Esquire Magazine and his book Rebellions, Perversities, and Main Events. I haven't read either of those books, but I did read Kempton's Esquire article and he also directly quotes Truman as saying "Never".

I agree that it seems really naive of President Truman to not think the Soviets would ever develop their own nuclear weapons. The only possible explanation that I can imagine for that mindset was that the meeting between Truman and Oppenheimer that is portrayed in the film took place in real-life on October 25, 1945. (In Kempton's Esquire article, he says it took place in 1946, but he was mistaken because Bird and Sherwin researched Truman's Presidential appointment calendar and were able to pinpoint the correct date.) The U.S. dropped the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6 and August 9, 1945, respectively. Japan surrendered on August 15 and the war officially ended when Japan signed the instrument of surrender on the USS Missouri on September 2, 1945. So, the meeting between Truman and Oppenheimer took place less than two months after the war finally ended. I can only imagine that Truman had still not fully shifted towards what the next conflict might be and was focused on trying to stabilize what was left of the world and mobilize the government in a different direction than it had been after 15 years of Depression, economic recovery, defense preparations, and fighting the war.

Plus, it's worth remembering that Truman didn't know anything about the existence of the American nuclear program until after President Roosevelt's sudden death thrust him into the White House and the military realized, "Oh shit, we should probably tell the new President that we're very close to building the most powerful weapon in the history of history!"

I don't think it was necessarily naivety on President Truman's part. I think, as Kempton suggests in the Esquire article, that is was just a fundamental lack of understanding by Truman that the Soviet Union didn't need Oppenheimer to build the bomb, especially since the war was now over and they wouldn't be under the time constraints or immediate pressures that made the work of the Manhattan Project so much more difficult. The knowledge was out there and the very fact that it had been proven by the Americans made it clear to the Russians and everyone else that it could be done. Harry S. Truman was a provincial politician from the outskirts of Kansas City who had a healthy dose of American Exceptionalism in him even before becoming a national figure, so the realities of nuclear physics were probably not easy for him to decipher.

#History#Oppenheimer#Atomic Bomb#Nuclear Weapons#Cold War#Harry S. Truman#President Truman#J. Robert Oppenheimer#American Prometheus#Kai Bird#Martin J. Sherwin#Murray Kempton#World War II#WWII

20 notes

·

View notes

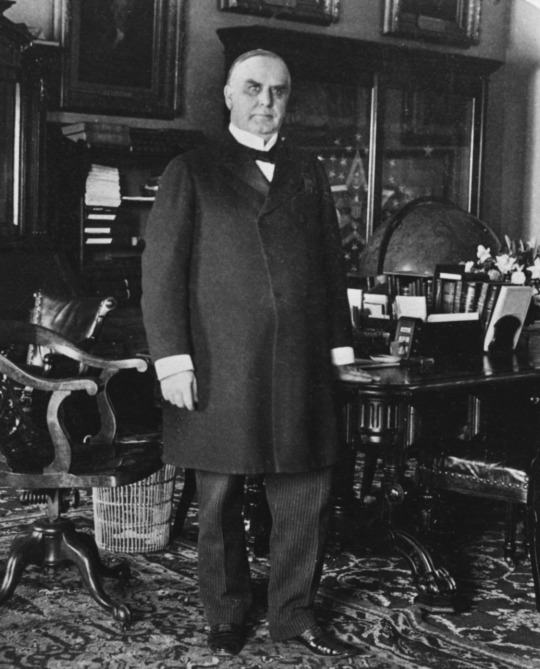

Photo

President Harry Truman was a self-taught scholar of presidential history. He had an assessment of every president who ever lived.

Truman said of the 1896 election of President William McKinley:

“The whole campaign was run by a man named Mark Hanna, who was a rich old man whose only interest was in getting richer, and that is what happened when McKinley got elected...

“He was another one of those who was good for the rich and bad for the poor...

“They say he was a nice man, and I’m sorry he got shot. But was still a damn poor president.”

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

'A whale or a lion or an earthworm is less inclined to go off in their heads than a human. No animal other than man suffers from congenital or acquired mental disorders such as depression or multiple personalities. We may hazard an explanation for this in the extremely complex and fragile wiring of our brains. Naturally, our default mode is insanity.

There is no reason why J Robert Oppenheimer, one of the most intellectually gifted, successful, and born-rich men of the 20th century, would suffer from bouts of depression till he died—of throat cancer in 1967.

Christopher Nolan’s eponymous movie, much debated, does everything right except bring alive the man’s torment, either before or after the bomb that Oppenheimer fathered and President Truman dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki—killing, according to one estimate, 2,20,000 people, most of them civilians.

Truman may not have been clinically mad, but he and his country had been fighting a war that cannot be said to be the finest expression of human reason. It must rub off in ways we are not equipped to tell because we are inside the matrix.

If those melted by the bomb, even one of them, were brought back to life by Nolan and confronted Cillian Murphy’s Oppenheimer, Oppenheimer’s remorse and guilt would have had an emotional punch the movie now lacks. Because when the dead come back, they always do so with more questions than the living can ever hope to answer.

In his essay on Gunter Grass, with special reference to the post-World War II novel, Crabwalk, J M Coetzee says: ‘Grass presents his apology for not having written and, sadly, for no longer having it in his power to write the great German novel in which the multitude of Germans (italics mine) who perished in the death throes of the Third Reich are brought back to life so that they can be buried and mourned fittingly … and a new page in history can at last be turned.’

Because of Oppenheimer’s connections at the time with the Communist Party of the US, he went through a sustained period of trauma, facing allegations of sedition and leaking sensitive information to the Soviet Union. Only as late as last December was he wholly rehabilitated, and the process by which his security clearance was cancelled (by the US Atomic Energy Commission in 1954) was declared ‘flawed’.

That a man who mastered nuclear forces and invented the atomic bomb for his country could be seen as an enemy explains how one’s fate is at the mercy of the careers of other men/women. If Hitler had remained a corporal as he was in World War I, content with the Iron Crosses he earned for his bravery and his soldier’s pension, and did not cherish a career in politics ending in his becoming the Fuhrer, millions might have had their lives spared. The role of an individual’s career in the destiny of civilisation yet awaits an author.

Indeed, had Oppenheimer’s ambition and drive for power not been so aggressive, he would not have accepted the post of director at Los Alamos Laboratory, which birthed the bomb.

In the movie, one of Oppenheimer’s lovers (Jean Tatlock, a communist party member, played with disturbing neurotic indeterminacy by Florence Pugh), in the course of a bedroom scene, picks out the Bhagavad Gita from the shelf, opens it conveniently at chapter 11, and makes Oppenheimer read the lines: ‘I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.’

The words are from Bheeshma Parva, in which Arjuna suffers from the ‘atomic’ equivalent of a nervous breakdown and would rather not take up arms against his elders and cousins; in short, he would rather not wage war. What good can come off such epic slaughter? But in the movie, the way it is played out, Oppenheimer never really has any great misgivings on his mission. They mildly assail him only after the bomb has been dropped.

The words come from one of the most egotistic chapters in all literature. Krishna annihilates the idea of Free Will for humanity. He is everything. Everything has been done. By Him. In Him, death happens. So does life. And all of it has happened once. All of it will happen again. There is no human agency. Arjuna just must carry out his dharma. In the great lines following, which Oppenheimer must have understood with keener insight than an average Indian, Krishna virtually licenses the dropping, thousands of years later, of the bomb: I have already killed Dronacharya, Bheeshma, Jayadratha, Karna, and other brave warriors. Therefore, worry not; slay them without a second thought. Do your duty, Arjuna.

Except for the appeal of Freudian association (Eros, love, and Thanatos, death, are virtually bedmates), it is not clear why coitus is interrupted for a short course on the Gita in the movie. Perhaps it augurs the destruction of Tatlot herself, who later commits suicide as Oppenheimer is reluctant to continue with the affair.

Despite the massive implication that we can all do great harm in the name of God, that if we are detached enough—having surrendered to the divine will—we are free to detonate a bomb, the nature of Oppenheimer’s career is markedly Faustian. He was ready to trade in death and make good in life. The US exploited Oppenheimer as much as Oppenheimer exploited the US. The amorality of either party does not find sufficient dramatic expression in Nolan.

Despite a boycott call by the right-wing Save Culture, Save India Foundation trending on social media, the movie has collected close to ₹100 crore at the Box Office. I suppose we have arrived at a stage in India where particle physics has become a matinee attraction. And at the same time, feel the need to save the Gita from Hollywood bedrooms. As I said, insane.'

#Oppenheimer#Bhagavad Gita#Florence Pugh#Jean Tatlock#Christopher Nolan#President Truman#Cillian Murphy

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Since I'm going to Independence, MIssouri this week (notice, kids, America trying to program you to be a freedumb fightin' independent even in the names of the places) ... I'd better watch a long documentary, or perhaps all three of them, about the President who was from there.

Truman's mother thought John Wilkes Booth was a great man and preferred Robert E. Lee to Abraham Lincoln.

Gore Vidal was not a fan of Truman, heh. My high school history teacher was, and Truman was his favourite president.

I'm at the part where Truman heads to Kansas City, which is right next door to Independence, of course.

0 notes

Text

Bethe was also one of the twelve American physicists* who challenged President Truman's decision in a statement dated 4 February 1950:

We believe that no nation has the right to use such a bomb, no matter how righteous its cause. This bomb is no longer a weapon of war but a means of extermination of whole populations. Its use would be a betrayal of all standards of morality and of Christian civilization itself . . . to create such an ever-present peril for all the nations of the world is against the vital interests of both Russia and the United States . . . we urge that the United States, through its elected government, make a solemn declaration that we shall never use this bomb first. The circumstance which might force us to use it would be if we or our allies were attacked by this bomb. There can be only one justification for our development of the hydrogen bomb and that is to prevent its use.

* S. K. Allison, K. T. Bainbridge, H. S. Bethe, R. B. Brode, C. C. Lauritsen, F. W. Loomis, G. B. Pegram, B. Rossi, F. Seitz, M. A. Tube, V. F. Weisskopf, and M. G. White.

"Brighter than a Thousand Suns: A Personal History of the Atomic Scientists" - Robert Jungk, translated by James Cleugh

#book quotes#brighter than a thousand suns#robert jungk#james cleugh#nonfiction#hans bethe#samuel k allison#kenneth t bainbridge#robert b brode#charles c lauritsen#francis w loomis#george b pegram#bruno rossi#frederick seitz#merle a tuve#victor f weisskopf#milton g white#harry s truman#president truman#february 4#50s#1950s#hydrogen bomb#nuclear weapons

0 notes

Text

They had expected a special public citation by the President as a reward for their services.

"Brighter than a Thousand Suns: A Personal History of the Atomic Scientists" - Robert Jungk, translated by James Cleugh

#book quote#brighter than a thousand suns#robert jungk#james cleugh#nonfiction#los alamos#soldiers#expectations#public citation#president truman#harry truman#reward

0 notes