#r.g

Text

Children of the Corn (1984)

#children of the corn#horror#movies#1980s#classic horror#gifs#film#linda hamilton#peter horton#john franklin#anne marie mcevoy#r.g. armstrong#robby kiger#1980s horror#courtney gains#my gifs#1984#1980s movies

521 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today in the Department of Before They Were Star Trek Stars, DeForest Kelley guest stars in "No Amnesty for Death," episode 25 of the third season of Bat Masterson (original air date March 30, 1961).

Kelley plays one of three men who are about to be hanged for their participation in the Lincoln County War when Bat Masterson arrives with a last-minute pardon, to the horror of the local sheriff, whose sons were killed in the conflict. As soon as the prisoners are released, they immediately rob a stagecoach and Kelley kills the driver. Masterson helps track them down, but instead of arresting them the sheriff starts a gunfight in which he and Kelley are both killed. Another perfectly good saloon floor ruined.

#star trek#star trek tos#star trek the original series#bat masterson#1960s tv#tv sci fi#tv western#deforest kelley#r.g. armstrong#james anderson#billy wells#gene barry

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dieu et La Fin de Satan or God and the End of Satan by Victor Hugo (tr. R.G. Skinner)

#quote#typography#dieu et la fin de satan#god and the end of satan#victor hugo#aesthetic#dark academia#light academia#french aesthetic#french#french studyblr#french literature#french poetry#literature#r.g. skinner

162 notes

·

View notes

Photo

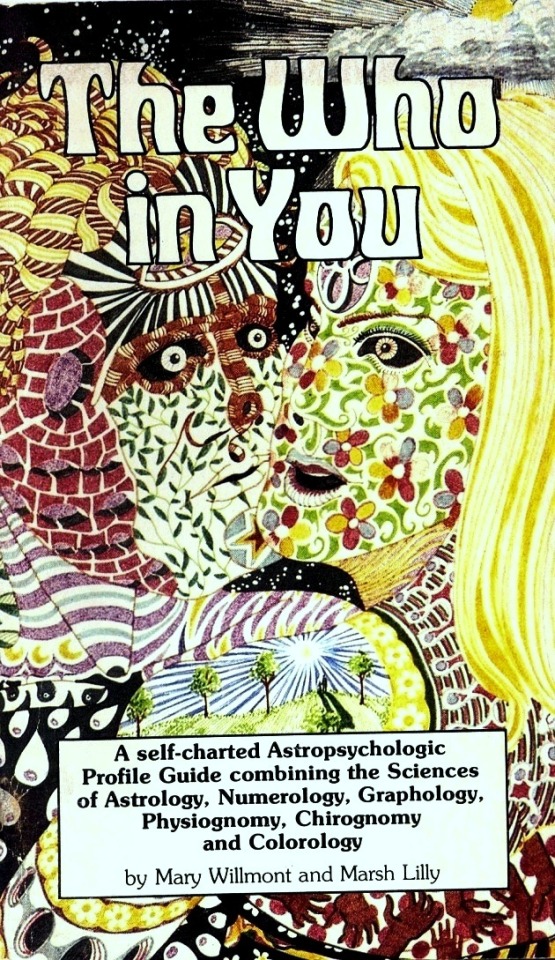

Mary Willmont and Marsh Lilly - The Who In You - Mary Willmont & Marsh Lilly Press - 1977 (illus . by R.G. Oleksyshyn)

#witches#yous#occult#vintage#the who in you#mary willmont#marsh lilly#self published#astropsychologic profile guide#astrology#numerology#graphology#physiognomy#chirognomy#colorology#r.g. oleksyshyn#1977

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

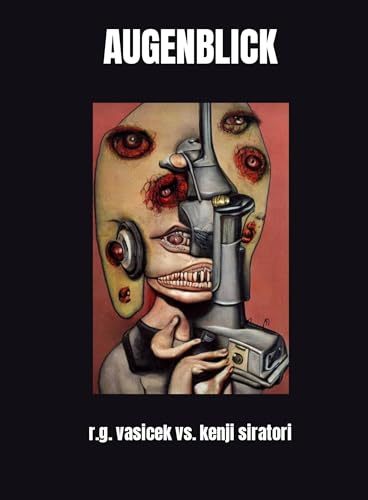

"What the fuck is this? What is this? I don't know. Maybe that is okay, not knowing, and maybe it isn't. These words, these phrases, these assaulting passages that strike like a tsunami are shattering the windowpanes of pure consciousness and disturbing the foundations of what has been whispered into our ear, by a robotic earworm, lodged in there. This creature has been there, as early as our conception on this wet planet, a metaphysical and physical thing that destroys all forms of continuity, rational thought, and reality, spreading the seeds of this elusive thing that has been drilled and planted into us, under the guise of fiction/literature, this thing called... art. This isn't a book. This isn't literature. This isn't normal. This will test you. And, the further you go, the more you realise, there is no goalpost, there are no markers to pinpoint and to use to map your way through it. It is this fusion of confusion and submerged identities and manifestos that screams for attention. It provokes you into skipping, forcing your way through the molasse of information and detail, and creating your own narrative from a cargo hold's worth of words, letters, and protein grain ruining your vision. You end up flipping through it and hitting pause on your meat machine, exacting a robotic process, selecting a phrase, a passage, a page, scrolling through the digital device, the paperback, breaking conformity and poisoning the expectation-devil sitting on your shoulder, the little bastard. This book can be read. This piece of art can be used as a physical weapon. This isn't the future. This isn't the present. This is definitely not the past. It is the in-between stages of corruption and renewal. In the blink of an eye, what was once a familiar word or letter transforms into something altogether ultra. Vasicek and Siratori have created a massive nuclear bomb of a "book." Augenblick is something altogether neu and alt. It is fucking impressive." Zak Ferguson (Author of My Body Meat & The System Compendium)

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

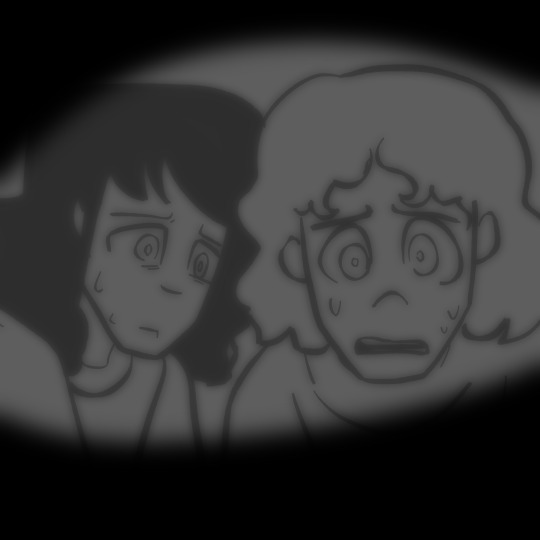

Ma’am?….. Hey! Hey…….. Wake up!

Ugh….. Where?

Lizzy: Wait — You two….

Ray Gordon? Sam Waters?

Ray: Oh good! You know us! Help!

Sam: Who are you? H-how?

Lizzy: Long story, but where are the others? Are you kids hurt?? Where are we?!

…..

Oh no….

#goosebumps#horrorland#goosebumps horrorland#fanart#l.m 📓#goosebumps fanart#digital art#art#R.G 😎#S.W 🐹#ray gordon#sam waters#lizzy morris#madison storm

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

El Dorado (1966)

Pulp science fiction writer Leigh Brackett was an anomaly in the genre. Not only was she a woman, but she also crossed over into Hollywood sporadically. Alongside her novellas and serialized stories, her film credits are enviable: The Big Sleep (1946; okay, this film’s story never made sense, but its romantic dialogue is legendary), Rio Bravo (1959), and, posthumously, The Empire Strikes Back (1980). To Brackett, she deemed her script to 1966’s El Dorado, a loose adaptation of Harry Brown’s novel The Stars in Their Courses, as “the best script [she] had done in [her] life.” High praise for oneself, especially as one could easily interpret El Dorado as a lighter, slightly more comic version of Rio Bravo. El Dorado was Brackett’s fourth of five collaborations with director Howard Hawks (1938’s Bringing Up Baby; the four other Brackett-Hawks collaborations include The Big Sleep, 1948’s Red River, Rio Bravo, and 1970’s Rio Lobo). Brackett’s inventiveness and spiky dialogue makes even the more clichéd elements of the story more entertaining than they should be. Other than Hawks and the ensemble cast, it is Brackett who is most responsible for the film’s success.

Somewhere in the American West, cowboy Cole Thornton (John Wayne) rides into the town of El Dorado for a job offer from local landowner Bart Jason (Ed Asner). His longtime friend, Sheriff J.P. Harrah (Robert Mitchum) meets with him, quickly deduces the reason for Cole’s presence in town, and effortlessly persuades his friend to turn down the job (the mutual respect for each other – between the characters and between Mitchum and Wayne – is apparent from the moment they meet). Jason’s job for to Thornton included coercing, gently or otherwise, the MacDonald family to abandon their land and water rights. The MacDonalds are an honest family, Harrah says, and they have been the target of regular harassment from Bart Jason and his men. Over the rest of the film, Harrah, Thornton, elderly deputy Bull Harris (Arthur Hunnicutt), a youthful gunslinger named Mississippi (James Caan), and Dr. Miller (Paul Fix) find themselves further embroiled in Jason’s repeated attempts to violently force the MacDonalds out.

El Dorado’s large supporting cast also includes saloon owner Maudie (Charlene Holt, whose character has a hankering for Thornton); R.G. Armstrong, Christopher George, Johnny Crawford, and Adam Roarke as the MacDonald boys; and Michele Carey as the hot-tempered Josephine “Joey” MacDonald (Carey and Holt play two of the final examples of the “Hawksian woman”).

Comparisons to Rio Bravo are all but inevitable to cinephiles and fans of American Westerns. Where Rio Bravo is more of a movie where friends revel in each other’s’ vibes, El Dorado is squarely a story of aging cowboys whose foibles – Harrah’s alcoholism to drown his self-pity, Thornton’s first act spinal injury and free-roaming ways – may spell the difference between local tragedy and justice. Despite what she might say, Brackett’s script to Rio Bravo (co-written by Jules Furthman) is far tighter than El Dorado’s, which employs a momentum-killing six-month time skip just as its dramatic interest begins to pique (editor John Woodcock does not provide any assistance here). It takes just a tad too much time for El Dorado, which uses the time skip to introduce Mississippi and sideline Harrah due to his heavy drinking, to regain the dramatic interest it established in the opening third of the movie.

Both casts of Rio Bravo and El Dorado have advantages over the other. Rio Bravo boasts Walter Brennan and Ward Bond in supporting roles (yet I’ve never been too fond of Dean Martin’s performance). El Dorado has Mitchum (whose dynamic with Wayne is fantastic), Caan (miles better than a Ricky Nelson sticking out like a rock 'n' roll kid from the 1950s), and not enough Asner. The two films, to me, are similar in quality, and I vacillate between which is “better” (but, on a rewatch, I think I might prefer El Dorado)*.

The interplay between John Wayne and Robert Mitchum lies at the heart of El Dorado. In 2024, it remains fashionable to lambaste Wayne for not being able to act and “playing himself” – an accusation that has been around for decades. With more lightly comedic material than usual (I would not consider El Dorado a comedy, but there are good-hearted ribbings and wry situational observances that prevent this from being a pure dramatic Western), Wayne revives some of the comic timing from The Quiet Man (1952) to decent effect here, especially around Mitchum and Caan. But most compellingly, Howard Hawks directs Wayne in a way that acknowledges and plays against his on-screen persona as the accomplished Western hero. Thornton’s spinal injury in the film’s opening act sees him reckon with his mortality – in jest and in seriousness. Wayne’s delivery and his physical acting is striking to longtime viewers such as yours truly, as it is one of the first films in which Wayne must come to terms with aging and his growing fallibility, as well as his reputation for outgunning and outthinking his opponents. The seeds of what would be Wayne’s late career signature performances in The Cowboys (1972) and The Shootist (1976) begin to show themselves here.

Mitchum, perpetually sleepy-eyed and always my first choice to play a slovenly protagonist good with a revolver, is wonderful here as a sheriff with the romantic maturity of a teenager who unaccustomed to rejection. The duality of Mitchum’s Sheriff Harrah here – the fastest gun for miles around determined to uphold the law and the inebriated slob who retains a sense of humor that makes self-pitying and self-deprecation indistinguishable – is difficult to pull off, but Mitchum does exactly that. Mitchum and Wayne’s historical on-screen personas are not polar opposites, but there is nevertheless little overlap between the two aside for their marksmanship. In their only screen appearance together (the two both co-starred on 1962’s The Longest Day, but their scenes were filmed separately), it seems the two have known each other for ages. The subtle glances, the knowing facial expressions, and gentlemanly warmth in conversation bely the fact that this is their first film together. But for El Dorado, their rapport benefits the film magnificently.

Like his good friend Ernest Hemingway, Howard Hawks admired masculine competence, professionalism, and self-reliance. El Dorado rambles a little bit about duty, honor, and loyalty, but all of this surrounds the central tenants of male friendship found here and in Rio Bravo. It is the development of that friendship and simultaneous professional excellence, rather than any plot details, that concerns Hawks – and this is the frame through which he wants viewers to see this film. By his own self admission, Hawks stated that he was, “much more interested in the story of a friendship between two men” than anything else in El Dorado (including fidelity to the original novel). The range war between Jason and the MacDonald family lacks as much exposition as some might expect. Hawks and Brackett refuse to fully explain how the dispute started, as well as what the conflict has wrought during the film’s time skip.

Those who are not as competent or professional – in this film’s case, James Caan’s character of Mississippi – are simply comic relief until they can prove otherwise. For those aware of Hawks’ aversion to Fred Zinnemann’s High Noon (1952) – in which Gary Cooper’s Sheriff Will Kane spends almost ninety minutes going around town asking for help when he learns a few recently-released convicts are coming to murder him (Hawks, to my consternation, considered this cowardly and a disgrace to the Western genre) – El Dorado is yet another reaction against it.

Unlike Hemingway, Hawks (who was by no means a feminist) rejects Hemingway’s reductionist portrayals of women as “Dark” (submissive lovers) or “Light” (castrating man-killers). The female protagonists in Hawks’ films, too, demonstrate tremendous ability. The saloon keeper, Maudie, is perhaps the most keenly observant individual in the entire picture, and can pick out the psychology of a person whether she has known them for ages (such as our leads) or if they have just stumbled in for a drink. She may be the smartest person in town. Her fellow Hawksian Woman is the wild-haired Joey MacDonald (her hair feels at times like an anachronism airlifted from the 1960s, rather than a likelihood of the Old West), quick on a gun and with a quicker temper. There is not nearly enough attention on either character as previous Hawksian Women (nevertheless, we need to recall what Hawks wanted to concentrate on most here, and that’s male friendship), but what there is still improves El Dorado’s watchability aside from our two leads.

youtube

A worthy score from composer Nelson Riddle (1960’s Ocean’s 11, 1962’s Lolita) dials back the main theme more than one might expect from a midcentury Western, but it is still effective music for this film. Riddle is best known as an arranger and orchestrator for the likes of Frank Sinatra, Nat King Cole, and Linda Ronstadt, not a composer. Nevertheless, arrangers and orchestrators can learn composition through osmosis if they have not already been trained in music composition. Riddle’s liberal use of harmonica perfectly captures the setting, although his use of electric guitar/bass and discernible lack of harmonic identity (especially in the strings) feels too much like television scoring from this era – Riddle was the principal composer for the 1960s Batman television series starring Adam West. Instead, the score highlights revolve around uses of the main title song and its variations.

And what about that title song? Sung by George Alexander and the Mellomen, with lyrics by John Gabriel (Dr. Seneca Beaulac on ABC’s soap opera Ryan’s Hope), “El Dorado” fits the film perfectly, and Alexander’s rich baritone musically exemplifies the masculine themes of El Dorado. Strings double underneath the vocals, with the occasional woodwind and brass section and peaking out from the melodic doubling (again, one wishes for more harmonic interest here aside from doubling the melody). A snippet of the song’s lyrics reference to Edgar Allan Poe’s poem “Eldorado”; the poem itself is recited by Mississippi. “El Dorado” is nothing but an earworm, and I just wish it (and its variations) made more appearances in the film itself.

Though Rio Bravo had elements of a changing of the guard, El Dorado cannot help but feel, by its conclusion, as a generational marker, a near-last hurrah – intentionally or otherwise. This is not, like The Wild Bunch (1969) or Unforgiven (1992), a eulogy of the Old American West. In 1966, El Dorado came at a time when the great figures of Old Hollywood and the height of the American Western’s popularity (Wayne and Mitchum) were no longer the dominant forces in American cinema. The film’s title song even opens with oil paintings from Western artist Olaf Weighorst, of evocatively overcast vistas of the West, as if in reflection.

El Dorado would be Leigh Brackett and Howard Hawks’ penultimate collaboration and penultimate Western, with Rio Lobo a few years away. Their professional partnership, so unlikely given Hawks’ status in Hollywood and Brackett’s supposedly disreputable day job as a pulp science fiction writer, is maybe one of the most underrated and undermentioned in Old Hollywood history – one that spanned the height of Golden Age Hollywood to its final years. For El Dorado, Brackett, despite a few structural missteps, once again shows her gifts for dialogue and a keen understanding of Hawks’ directorial intentions. Hawks arguably improves upon his depiction of male camaraderie from Rio Bravo, allowing our protagonists to intuit their aging (some might say obsolescence). This is a sterling Western, if slightly out of time.

My rating: 8.5/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating. My interpretation of that ratings system can be found in the “Ratings system” page on my blog. Half-points are always rounded down.

* As of this write-up’s publication, I have not seen Rio Lobo (1970), which forms an unofficial trilogy of Westerns with Rio Bravo and El Dorado.

For more of my reviews tagged “My Movie Odyssey”, check out the tag of the same name on my blog..

#El Dorado#Howard Hawks#John Wayne#Robert Mitchum#James Caan#Charlene Holt#Paul Fix#Arthur Hunnicutt#Michele Carey#Leigh Brackett#Ed Asner#R.G. Armstrong#Harold Rosson#John Woodcock#Nelson Riddle#Harry Brown#TCM#My Movie Odyssey

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

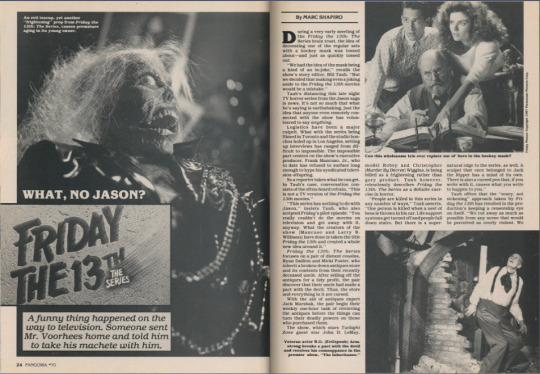

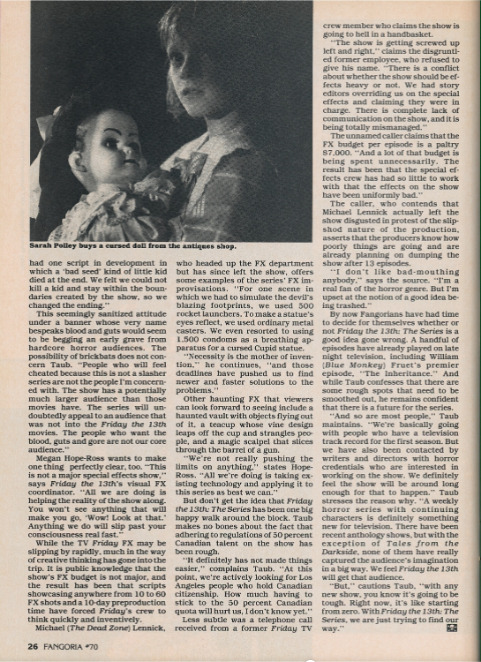

Early article at the beginning of the series run, citing hope for the show, as well as behind the scenes struggles.

#fangoria#80s tv#80s#article#friday the 13th: the series#john d. lemay#robey#louise robey#chris wiggins#r.g. armstrong#megan hope-ross#bill taub#william taub#marc shapiro#micki foster#ryan dallion#jack marshak#curious goods#fangoria 70

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Merhaba, ben yalnız. Tek başınalığın kurduğu krallığın ıssız bir üyesiyim. Oradayken uzun uzun dünyayı izledim. Kalabalıkların krallığımızdan korktuğunu öğrendim, onu istemediklerini, sevmediklerini. Zaten bir çoğu istemeden gelmişti krallığımıza, çıkmak isteyenlerin çığlıkları bulaşıyordu tenhalığıma zaman zaman. Merak ettim dünyalarını, bu kadar özledikleri şeyin ne olduğunu. Kalabalık dünyalarını bu kadar üstün kılan şeyin tam olarak neyle ilgili olduğunu. Kısa bir süre önce keşfe çıktım. Şimdi krallığın kalabalıkta kalan ıssız bir üyesi olarak yazıyorum bu satırları, bizim dünyamızdaki başka bir ıssıza; Bil ki burada durumlar daha farklı değil, burada da kimse daha mutlu değil."

119 notes

·

View notes

Text

There’s something about a woman with a loud mind that sits in silence, smiling, knowing she can crush you with the truth.

– R.G. Moon

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

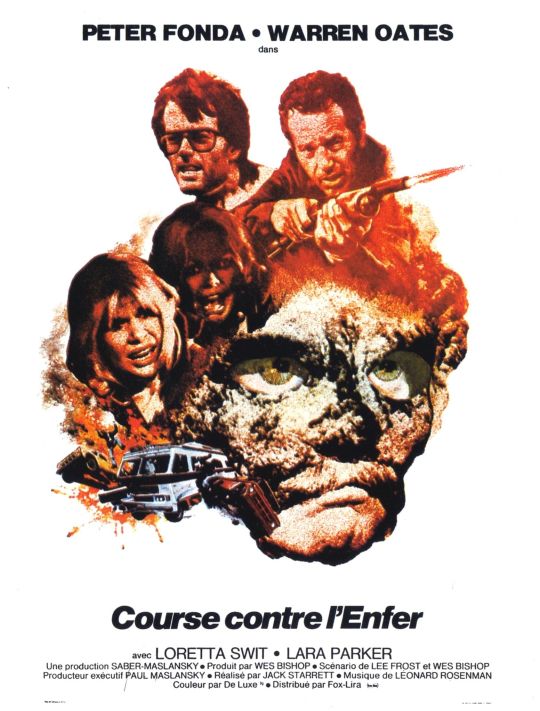

"Corrida com o diabo" (race with the devil) - cinema.

Double feature no IMS! Esse era o primeiro, menos conhecido que eu não tinha assistido. Nem sabia da sua existência até aparecer na programação do IMS. Desavisados presenciam cerimômia diabólica e passam a ser perseguidos pela seita. Elenco com Peter Fonda e Warren Oates.

depois de ver: acredito que se não fosse a nudez, esse filme seria uma sessão da tarde clássica nos anos 1980. ótima cena com as cobras e perseguição final usando um motorhome (!).

#Corrida com o diabo#cinema#Race with the Devil#Jack Starrett#Peter Fonda#Warren Oates#Loretta Swit#Lara Parker#R.G. Armstrong#1975

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dieu et La Fin de Satan or God and the End of Satan by Victor Hugo (tr. R.G. Skinner)

#quote#typography#literature#poetry#victor hugo#god and the end of satan#dieu et la fin de satan#aesthetic#dark academia#dead academia#r.g. skinner#angels#monstrum#dark things#divinity

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

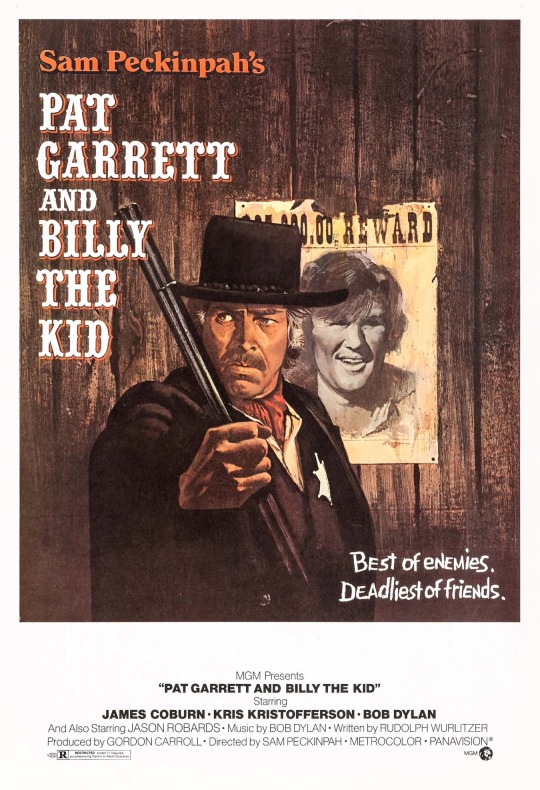

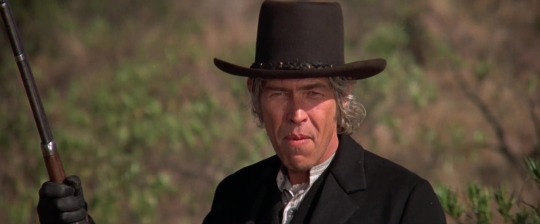

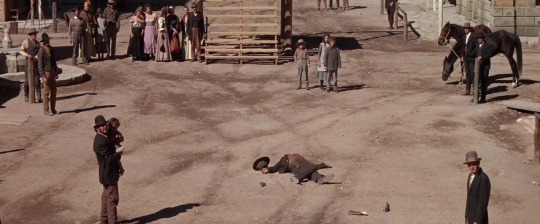

Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid (1973, Sam Peckinpah)

8/6/23

#Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid#Sam Peckinpah#Kris Kristofferson#James Coburn#Richard Jaeckel#Katy Jurado#Chill Wills#Barry Sullivan#Harry Dean Stanton#Jason Robards#Bob Dylan#R.G. Armstrong#70s#drama#western#true story#sheriffs#Billy the Kid#Pat Garrett#New Mexico#19th Century#outlaws#buddies#frenemies#friendship#masculinity

6 notes

·

View notes