#scientific literacy

Text

Most people who believe in some "weird" thing like magic, ghosts, extraterrestrial visitors, cryptids, or whatever are not "anti-science." They generally believe that science is fundamentally correct about most things, but cannot adequately explain the "weird" thing they believe in.

If there is strong evidence against said weird thing, it's much more likely that they're just unaware of it, rather than being aware of it and actively choosing to disregard it. It's also more likely that they're unaware of scientific models that adequately explain it, rather than choosing to completely disregard said models.

Also, some people have genuinely had bizarre experiences that scientific models simply cannot explain yet. Like "three people in a small community independently had the exact same prophetic dream about an event they had no reason to expect" kind of bizarre. And when shit's this weird, the "scientific" explanations are just insultingly reductive.

Scientific literacy is good and should be encouraged, but being rude and dismissive to people who believe in "weird" things isn't the way to go. Most people who are into "weird" stuff tend to be curious by nature, so if you just present them with accessible scientific material that doesn't talk down to them, they'll often happily dive right in.

694 notes

·

View notes

Note

why do you trust psychs and their findings? it's a fucked up system, sad to see you fall for it

So I've had this in my ask box for a while mostly because I felt it was both kind of silly and very presumptuous (not to mention condescending).

I read research because I don't trust people. If you know How to read a research paper, you will be able to tell if the conclusion is a bit of a leap, if their method makes sense, if their sample size is good, if the demographics are not representative, etc. I don't "trust" findings and I don't "trust" the researchers writing them, I weigh the findings based on all that prior info and decide whether the findings make sense to me. I don't mean this to say that I'm special for being able to do so, but that if you develop the skill then you can Also do that.

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

How to check if a source is credible. Misinformation is straight up killing people

via reddit: What’s some basic knowledge that a scary amount of people don’t know?

EDIT: How to actually check if a source is credible:

- Identify the author and check their credentials. Also, see who their employer is, and consider how it might impact their biases.

- Compare headlines to the actual content of the article. Is it intentionally misleading to provoke an emotional response? Think about whether it's done to intentionally misdirect people.

- Check the date the article was published. When it was released could change if the information is outdated.

- Fact check the story by using websites like FactCheck.org.

- Dig deep to see if the news article cites sources and traceable quotes.

- Check if the URL has any misspellings or odd use of language.

Important things to remember:

Always consult multiple sources - Social media is NOT a reliable source (looking at you, Facebook)

- Be open minded and fight against confirmation bias.

- Avoid predictive searching so you don't get trapped in an echo chamber.

—

P.s. I save quite a few things from Twitter. When I do, I look who posted it, what their credentials are, if that's corroborated elsewhere, who else endorses them, etc. (Usually it's from researchers whose work I already knew from years back.) That doesn't mean they or the info is certainly infallible; it's just due diligence, to the extent I can.

If something is incorrect, I want to know. But likewise I'm skeptical depending who says so, what their credentials and sources are, and always: cui bono?

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

People on this site will complain about media literacy and then completely forget that scientific literacy is an equally prevalent and important issue in the US.

Seriously, most adults can't correctly interpret a research paper's findings. Most adults think science and experimentation prove/disprove things. Most adults aren't even aware of science being limited to falsifiable statements.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

How does science fiction television shape fans' relationships to science? Results from a survey of 575 ‘Doctor Who’ viewers by Lindy A. Orthia

Fiction is often credited with shaping public attitudes to science, but little science communication research has studied fans' deep engagement with a science-themed fiction text. This study used a survey to investigate the impacts of television series ‘Doctor Who’ (1963–89; 2005–present) on its viewers' attitudes to science, including their education and career choices and ideas about science ethics and the science-society relationship. The program's reported impacts ranged from causing participants to fact-check ‘Doctor Who’'s science to inspiring them to pursue a science career, or, more commonly, prompting viewers to think broadly and deeply about science's social position in diverse ways.

Read the full article

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Informal Explanations of Behavioral Research Concepts; Concept Validity

So I'm internally monologuing to myself about animal behavior research and how it compares to human research and the number of difficulties between it and the bridge between these two fields honestly highlights a great issue of concept validity which is why human behavior, emotions, and research on self have not really been able to break into the field of animal research which for stuff like medical issues has RAPIDLY accelerated findings and insights to how humans work

One of which that I've read the most on during my time studying animal behavior in academics was the idea of researching the concept of fear in animals. It sounds relatively straight forward, illicit fear in animals, measure that fear, bing bang boom easy

But you first have to ask a few questions to build that.

What is fear? How do we measure fear in humans? Is that measurement actually a good depiction of fear? Is what we think fear is a good description to what we are actually trying to study for the purposes of long term research?

Fear is a very subjective concept to start with. Ask 40 different people to describe and define fear and you will get many many many different answers. Some would describe it based on the biological reactions - amygdala activation, cortisol, etc - some might describe it on its behavioral aspects - avoidance, arousal - some might describe it on self reports - psychometrics and surveys - and some might describe it in a very ethereal manner that can't really be measured - some might mix and match these. To research fear in humans, we have to understand what fear is and what we are researching and any differences in the definition of fear that the researcher takes on will inherently change how the data is collected and interpretted. Data that talks about fear (purely biological and measuring activation of the amygdala) will likely have wildly different results than data that talks about fear (psychometrics and self reports) and data that talks about fear (behavioral measures and tracking). Which is the most accurate and most valid description and understanding? Which works the best to address the larger question in hand that you are meaning to look into? There is no real clear cut objective right answer and thus talking about "research in fear" will result many conflicting results not only due to many other complications in research but ALSO just different approaches to the concept of fear.

This is questioning the researcher's concept validity of fear in human research.

Do animals feel fear? If some do and some don't what animals do? What would fear look like in different species considering the lack of ability to directly communicate (with most) species despite the many different forms, biological and neurological differences? For species that have notably different brain structures and development (birds vs primates; insects, etc) how can we know that fear is even a possible expression that their brain can generate and not simply a human inferrence and transference assuming that our experiences are the same with animals? Additionally, how would we measure fear in animals? Is that measurement reliable? Is it actually a measurement that matches our definition of fear? Is that definition of fear actually in line with what we are trying to study for the purposes of long term research?

While humans have a tendency to assume all animals experience the same things as us, it is proven to be a very disservice assumption that underlies a lot of animal welfare issues that - as researchers realized it is often not the case - have been remedied in some locations but not others (cough cough ARAs cough cough). The truth is, animals have wildly different biologies than humans from the way they take in sound, vision, feelings, to how they process food and even their brain structures. As a result, it is heavily presumptuous to assume that any subjective and more ethereal emotional concept like "fear" is not only present but also present in the same way as humans and that stages a huge difficulty in the research of animal emotions and welfare states. Currently, this field is pretty young and in its infancy so there is limited understanding and consensus on the best way to navigate this and so there is a lot of discourse on what the HELL we are considering "fear" in animals and if it is even fair to call it that. Fundamentally, we have to heavily consider the concept validity of "fear" and even its existence and how we approach it when researching animal behavior.

Additionally, even if we do assume that, we have a large communication barrier between animals and humans and thus we are not able to rely on self reports (even with some 'communicative animals' like apes and parrots as there is discourse as to if that is "genuine" communication or learned) so we are forced to rely on behavioral and biological measurements - which in itself pose an issue due to the different morphology across species.

Additionally, when researching fear across species (particularly human and animal) - are these measurements measuring the same thing? Are the definitions the same? Do they both address the same type of fear in concept, definition, and measurements? How do they differ? How do the inherent differences in morphology impact the results and how much do those differences need to be taken into account?

ASSUMING that we take the claim that animal fear and human fear are the same and comparable, if we were to compare one to another, we would need the data and concepts of fear to be matching otherwise direct comparisons are not going to be all that fair as one measurement may be biased due to it being defined differently or measured differently. Of course it can be hard to have this ideal perfect match up and so often people accept that there will be this difference, but that does come at a cost to the validity of the concept itself. A study that measures an animals fear based on behavior would have to justify that it is a valid comparison to say a human measurement of fear through a combination of behavior and self reports and what not.

As a result to the researcher interpretting all these questions differently than another, the results can vary drastically and many many different and opposing conclusions can be made.

In turn, to the complex topic of DID and syscourse where the concept of DID and "plurality" and what not are VERY VERY VERY ethereal and esoteric, we have to ask what exactly are we defining, how are we measuring them, and how does that definition and measurement compare to the practical phenomenon itself that we are interested in?

Every approach will have its strengths and weaknesses, its more valid corners and its less valid corners, and it largely depends on what the overall long term research interest is. Someone interested in the experience of people who live as multiple people will be researching and coming to conclusions wildly different than someone who is interested in the experience of people who have survived complex and repeated trauma by developing strong dissociative states. Neither interpretation is inherently wrong or better than one another and they are answering the questions of concept validity of their research target very differently from one another simply due to the fact that the overarching interest is different.

That said, the differences and background and interpretation of the phenomenon that we are discoursing about needs to be taken into consideration when discussing and understanding research literature on the topic. A sociologist will answer it different than a clinical psychologist who will answer it differently than a neurologist because each of them are interested in a slightly different long term research goal than the other and that is netiher wrong nor bad. It is the intersection of all these different long term research interests that help build a much larger image of a very very complex and intangible concept such as DID/plurality/multiplicity etc

#syscourse#discourse#research rambles#research#alter: riku#research literacy#scientific literacy#riku rambles#concept validity

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is Christine Jorgensen, a transgender pioneer. The way her story evolved is incredibly sad: an initially curious and enthusiastic public turned to hate — because they would not accept a sterile woman.

Excerpts below from a VICE article by Hugh Ryan

(warning for possible triggers; hate speech after 2nd paragraph):

“Christine's celebrity happened at a very particular time in US history,” said David Serlin, a Professor of Communications and Critical Gender Studies at UC San Diego and the creator of the CJMB. He pointed out, “There was this incredible enthusiasm for science,” and Jorgensen’s transformation was seen as a triumph of modern medicine. The public’s initial response, he said, was, “We are building rockets, we can cure illnesses, and we can take a boy from the Bronx and turn him into a glamorous woman!”

...

This question of realness would end up being Jorgensen’s undoing, Serlin told me. Part of her celebrity had to with America’s love of science, but the rest had to do with how little anyone knew about sex reassignment surgeries. Her peers, even those in the nascent homophile movements of the 50s, had no context for gender transitioning. There was no T in the vague LGB movement, and the word transgender hadn’t even been coined yet. Of course, people with cross-gender desires have always existed, and a few earlier pioneers had also undergone experimental surgical gender reassignments, but they didn’t have a public face in America until Jorgensen, according to GLAAD.

Serlin speculates that at first most Americans “really thought Christine was menstruating and had eggs in her fallopian tubes.” But after six months, the press began to ask more probing questions about what her surgeries actually entailed. When they didn’t like the answers, the country “went ballistic.” Gender panic took over, said Serlin. “They said, ‘He's not a woman. He's just a neutered faggot.’” Reputable magazines like Time stopped using female pronouns for Jorgensen, and coverage of her took on a nasty, speculative air.

America didn’t have a huge problem with someone switching between two discreet and very separate sexes, but the suggestion of some middle ground, of a spectrum between male and female, made people fearful and angry. Jorgensen’s existence and acceptance as a woman implied that gender and the body were not necessarily connected, that gender was something one worked to create. If this were true, the sex-segregated ideals of post-war suburbia would have been out the window. In the eyes of the public, Jorgensen was no longer a man-made woman, but a gender terrorist in a blond bouffant.

...

our awe came first and our hatred came after ... America stumbles towards every new thing like a delighted (but dangerous) toddler, and that our present moment is just another moment waiting to be changed.

#Christine Jorgensen#trans#trans rights#lgbtqplus#womens rights#women#historical#science#scientific literacy#science enthusiasm

61 notes

·

View notes

Photo

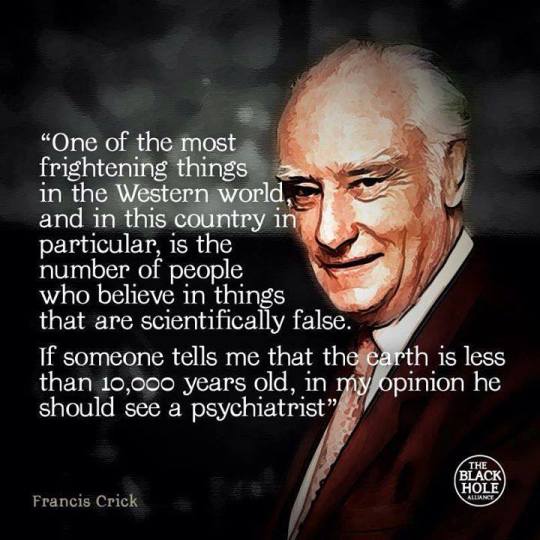

"One of the most frightening things in the Western world, and in this country in particular, is the number of people who believe in things that are scientifically false. If someone tells me that the earth is less than 10,000 years old, in my opinion he should see a psychiatrist”

-- Francis Crick

#Francis Crick#scientific literacy#scientific illiteracy#scientifically illiterate#science illiterate#science illiteracy#young earth creationism#young earth#young earth creationists#delusional#science#religion is a mental illness

84 notes

·

View notes

Note

do you have any resources for figuring out the source of chronic joint pain? ive done some searching myself but its hard to find anything that isnt just talking about rheumatoid arthritis

unfortunately i don’t have like one source i can direct you towards but hopefully some of this is a helpful starting point!

afaik the most common causes of joint pain are rheumatological (rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, lupus/SLE, Sjögren’s, fibromyalgia), secondary to inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s or ulcerative colitis), Lyme disease, or due to hypermobility such as EDS. this list (link) from the Mayo Clinic includes rarer causes

my general diagnosis research advice, in no particular order, is:

if you developed symptoms before 18, refer to both adult and juvenile information

look at actual diagnostic criteria, not just summaries. often symptoms are weighted differently according to frequency

focus on any distinctive (common) differences between conditions because often there’s a lot of overlap

if a condition seems to overlap with some aspects of your experience but not others, look into those specific differences - information may be outdated or oversimplified. for example, recent studies show AS is equally common regardless of gender but articles will still say it’s more common in men, people can have seronegative RA (negative blood test for rheumatoid factor), etc

read sites geared towards doctors, such as continuing education sites, for more detailed and accurate information

search PubMed and skim for any recent breakthroughs in diagnosing/classifying a certain condition

search tumblr and other social media platforms to get an idea of what symptoms people who have a certain condition/diagnosis actually experience

keep in mind that if you’ve narrowed options down to something treated by the same medications (for example: RA, AS, psoriatic arthritis, and IBD can all be treated by Humira), then which particular diagnosis you receive isn’t that important

i highly recommend checking out DermNet New Zealand (link) if you experience any dermatological symptoms (skin, nails, hair) - they have click/hovertext definitions of terms, very thorough lists of potential diagnoses for symptoms, acknowledgments that differences in prevalence could be due to bias, and usually include example images of what conditions look like on non-white skin

best of luck to you and i hope you get some answers soon 💕💕

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hello everyone!

I am a geology master's student finishing my degree this December. I'm currently focused on studying lunar meteorites!

I don't entirely know what I'll use this blog for, but I hope it will be educational and fun!

I really love doing community outreach and science education, so I hope I can use this blog for that purpose.

I also think it's important to improve scientific literacy, which means I think everyone deserves to feel confident they can tell the difference between a good article and bunk science.

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi, just curious! Are there problems with how research is done?

Oh, huge can of worms. Here's a post I made about basic scientific literacy. But I'll touch on problems here instead of basic stuff like stats.

1) Funding bias. This Should be disclosed in more modern research but sometimes still is not. But basically research teams are...not exactly swimming in cash (side tangent please support PhD researchers in trying to secure better pay and better working conditions). They have to request funding from Somewhere--university money, govt money (NIMH etc), corp money (pharmaceutical companies), or private funders (think SpaceX). That means that researchers can feel pressured to report things that those parties Want to hear in order to get money to do their research. Looking up who the funder is should give a pretty clear idea. This is Typically more of a problem for pharmaceutical research for psych and privately funded/other corporation research for most other things. So make sure to check out who funded something.

2) This isn't technically funding bias but is still funding related and is a major pet peeve of mine. But often there are a lot of things that researchers WOULD absolutely research, but the problem is that it never gets funded because the people with money don't think it's important/interesting enough. If you get very good at reading research you can tell when researchers really want to study a specific thing but they weren't allowed to so they did something tangentially related. Big huge thing that rarely gets funded is longitudinal studies, because...well. It's expensive. But there's a lot of stuff that would deeply benefit from longitudinal views.

3) Publication bias. This is more about research Not getting published than the fact that the published stuff is "bad" per se. But whenever research is conducted, the research team pays for a research journal (there are many, but usually you don't apply for multiple at once due to cost) to look over their paper and decide whether to publish it in or not. The journal has a team of reviewers who rate the paper on a scale and if there's editing stuff to be done and so forth. The good side of this is that reviewers are neutral 3rd parties that can catch things like poor methodology etc and on a more minor note things like typos or word choice. The bad side of it is that sometimes research that "has been done" or is not considered "interesting enough" doesn't get published. So basically more sensationalist or groundbreaking papers get published than the more "boring" stuff but many times the boring stuff is kind of pretty important.

4) Research limits. So, I talked about demographic and sample size in the post I linked. But sometimes, particularly for less common conditions, there simply is never a representative sample. For rare things, you might only get case studies of 1-2 individual people per paper. If you are in NY for example, and you have to have people physically in your lab to conduct tests, and they all have to have x condition that occurs in 1% of the population. You theoretically have 1% of your state to work with, but then you factor in whether people are willing to drive to you, whether they meet your other criteria like age range, or they have a bunch of comorbidities that you can't begin to untangle, then they also have to Hear about the study so where are you marketing, then they have to Agree to be in the study and then they have to Keep Going to your study (many people drop out for various reasons during the course of a study). At the end of the day you may be have 50-200 people to work with and maybe there's an overrepresented demographic or two. There's also stuff like ethics to consider but I don't consider that a "limit" per se...like for example the reason why children aren't studied to "make sure" trauma is what really causes DID is because they would have to knowingly leave or put children in traumatic situations to do that.

5) Ok pet peeve #2 time, but speaking of comorbidities. Studies will usually exclude people for having comorbid conditions (unless they're specifically looking at how the conditions interact). This is for the simple reason that they can't account for how all that other stuff is affecting their results. Some of it might seem "obvious," but science doesn't really do "obvious"...it's meant to eliminate as much bias and assumption from the researcher as possible. Downside of this is that very very few people are as simple as research would like them to be. There's not really a solution to this, just something to keep in mind.

6) Speaking of! The researchers themselves. You will see strongly opinionated papers, particularly in lit reviews and in meta analysis (I personally really like watching 2 researchers duke it out but instead of being normal about it they just publish papers back and forth shittalking each other. Not very useful info in their papers though). More subtle/hard to see on paper, but researchers are people and unfortunately that includes all the nasty shit that people come with, like bigotry. This can affect how they treat research subjects as well as how they interpret those peoples' results. Double blind studies are nice for this because noone knows who got what results or what their demographics are, but not every study can be double blind.

7) Research work environment. Hinted toward this with the higher pay and whatnot but a lot of PhD researchers are severely overworked and very underpaid. A lot are making roughly $20-30k/year while juggling research, teaching, publishing, conferences, sourcing funding, and continued education, while trying to pay off their student loans. And some universities don't pay them over summer breaks so they also often have Another job. There is also the beaurocracy to deal with, the fact that sometimes they are expected to pay out of pocket (rather than through the funder) for things like the research publication application or panel reviews, and...there is a significant amount of sexual harassment and racism etc from PIs who they often are not in a position to argue with or report. This means that stuff probably gets missed, often, or the data drawn doesn't really match up with their conclusion because they're running on empty.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

It is hard — re: "when you look out the window or when you’re out in your N95 and see 99% of the population going about things as if there’s no pandemic."

It is hard.

It helps me to remember that what we see outside is factually not 99%, just our own anecdotal sample. Some larger than others: I live in one of the most populated, traveled-to cities in the world and see a royal shit-ton of people every time I go outside — yet another reason I join the few masking.

(I get it that in other, less crowded places things look different; that's a contributor to confusion online. My city problems may not make sense to someone in the suburbs, but we're in the same discussion without any context.)

OTOH, I look at the data and know that outside, I won't see the invisible others. Those who are IC, have LC, etc. Of course they/we group online, since that's the only place to safely be and discuss.

I also know that people, even those who are informed, value social norms. E.g. Dr. Fauci going to some event and removing his mask because others were, then getting covid. And here's a good thread: https://twitter.com/Helenreflects/status/1641003804584972289

So I think a combination of a few factors contribute to those still masking; any single one may not be enough:

being closer to the nonconformist end of the spectrum to begin with (i.e. "I care about people; less so what they think.")

being informed, scientifically-literate

cultural (conforming, but to a different group)

those who've experienced chronic illness (not just the physical aspects but also how others react short and long-term...

and the resulting distrust built up from that: lack of, or lack of trust in the strength of safety nets — social and financial

likewise, those who've experienced gaslighting (this term is overused lately, but having experience with that can lead to personal high valuation of fact-checking and record-keeping, and again a lower regard for what some others are doing or saying)

privilege / circumstances (e.g. it may be harder for someone with kids; they might be more likely to be more fatalistic if it seems insurmountable. or e.g. this person's BF who probably felt high pressure due to this mandatory work event: https://www.reddit.com/r/WitchesVsPatriarchy/comments/11h3ciu/comment/jart4aj/?utm_source=reddit&utm_medium=web2x&context=3)

#covid#masking#still masking#long covid#chronic illness#safety nets#gaslighting#scientific literacy#nonconformity#conforming#personal stories#commentary/opinion

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Looking at a Systematic Review of Environmental Risk Factors for Child Stunting

Child stunting, characterized by impaired growth and development, is a significant public health concern globally. While nutrition plays a crucial role, there are other environmental factors that contribute to this condition. In this blog post, we will delve into the findings of a systematic review conducted by Vilcins et al. (2018) to highlight the key environmental risk factors associated with child stunting. This research sheds light on the multifaceted nature of stunting, beyond nutritional aspects, and provides valuable insights for effective interventions.

Household Air Pollution:

The systematic review by Vilcins et al. emphasizes the impact of household air pollution on child stunting. Exposure to indoor air pollution from sources like solid fuel for cooking and heating, such as biomass or coal, can lead to respiratory infections and chronic inflammation. These conditions can impair a child's growth and development. For instance, in regions where solid fuel is commonly used, such as parts of Africa and Asia, children exposed to high levels of indoor air pollution have an increased risk of stunting.

2. Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (WASH) Practices:

Inadequate access to clean water and sanitation facilities significantly contribute to child stunting. Vilcins et al. highlight how poor WASH practices, including limited access to clean water for drinking and hygiene, and inadequate sanitation facilities, increase the risk of infectious diseases and nutrient deficiencies. For example, in areas where open defecation is practiced, the risk of stunting is higher due to the increased likelihood of fecal-oral transmission of diseases like diarrhea and intestinal parasites.

3. Environmental Contaminants:

The presence of environmental contaminants, such as heavy metals and pesticides, is associated with child stunting. Exposure to these pollutants, either through contaminated soil, water, or food, can interfere with a child's growth and development. For instance, in agricultural communities where pesticides are extensively used, children may be exposed to these harmful substances, which can impair their cognitive development and contribute to stunting.

4. Poor Housing Conditions:

Inadequate housing conditions, including overcrowding, lack of ventilation, and dampness, are identified as risk factors for child stunting. These conditions increase the likelihood of respiratory infections, which can impact a child's nutritional status and growth. For example, in slum areas with crowded living spaces and insufficient ventilation, children are more susceptible to respiratory illnesses, leading to stunting.

Vilcins et al.'s systematic review highlights the environmental risk factors associated with child stunting beyond nutritional aspects. Household air pollution, poor WASH practices, exposure to environmental contaminants, and inadequate housing conditions all contribute to stunting. Addressing these factors requires comprehensive interventions that improve access to clean energy, promote proper WASH practices, reduce environmental pollution, and enhance housing conditions. By understanding and addressing the environmental risk factors associated with child stunting, policymakers, health professionals, and communities can work together to develop effective strategies for prevention and intervention. It is through targeted actions and investments in improving environmental conditions that we can reduce child stunting rates and ensure healthier futures for children worldwide.

References!

Vilcins, Dwan, Peter D. Sly, and Paul Jagals. "Environmental risk factors associated with child stunting: a systematic review of the literature." Annals of global health 84.4 (2018): 551.

#medical anthropology#medicine#global health#global medicine#child stunting#paediatrics#social determinants#systemic review#anthropology#scientific literacy#environmental factors

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Non-dualism and logic

Is it the answer to questions, or is it just more questions? Do we see a lot of things around us, or are we missing many more things that exist? This is my take on looking at ourselves and our world with logic, not eyes.

What should one follow – a religion, belief system, spirituality, or ‘how-to’ guide? I don’t know the answer to that, and nobody does because the one you are following may also be following someone else, and the chain may be going on and on. So, who are you following in the end? Nobody knows, and neither do I. But I know one thing for sure – I am on a path to understanding the world around me,…

View On WordPress

#3D#advaita vedanta#astronomy#bhagavatham#big bang#cognizance#common sense#consciousness#dimensions#fake illusion#Hubble telescope#James Webb Telescope#knowledge#logic#math#non dualism#priyafied#sanskrit#scientific literacy#suriya siddhanta#theory of everything#time#unified#unified force of nature#universe#vivekachudamani

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello, I’m curious about what this post means?

https://www.tumblr.com/system-of-a-feather/718445430628859904/ok-people-equating-the-theory-of-structural

If you don’t mind explaining, that is! Aren’t they both scientific theories? /gen

(I got to sleep in today weekends are great ;w; *is in a better mood and has energy to explain some to someone genuinely asking since this is a thing that hurts me about the internet and how they talk about science*)

"Aren’t they both scientific theories?"

Yes, but only in the way that you can say that apples and tomatos are both fruit (true) and should be put in a fruit salad (debatable by which study you go to and the context in which you discuss it) - or that fish and Chordata are both existing things (for those that don't know either through school or memes, "fish" don't exist claudistically / in taxonomy, they are a polyphylic group)

.... while I'm doing comparisons, I think its actually fair to say that its more inaccurate than comparing apples to oranges - its comparing apples and tomatos - but I digress that's just a distracting "heh" I thought of XD

Putting the analogies aside and explaining it properly - they are both "scientific" in the sense that they are both following and part of the very very very very broad term of "science". With that being said, science in practice and when understanding research - when talked about in such a general way - is much more an ideal and a concept like Bushido Code than it is an actual like.... Facts TM and Truths TM about the world.

When we talk about stuff like the theory of evolution, gravity, the scientific theories we easily and frequently label as "basically as close as you can get to fact" we are almost always talking about hard sciences such as biology, chemistry, physics - sciences that have a relatively simple / easy time (relatively) in terms of research design, validity, and verifying data. Hard sciences (again, relatively speaking) tend to collect and base their theories on unchangable, (relatively) simple functions of systems that they are investigating, and their data (relatively) are hard and firm as they are directly measuring an aspect of the system they are investigating and (comparatively) the concern on concept, criterion, face, predictive, external, internal, (etc) validity is not really as significant. The things that hard sciences are investigating are far more "unchanging rules of the world base in hard to accidentally or intentionally spoof measurements" than soft sciences.

Psychology - a soft science - doesn't (often) work on measuring hard and (relatively) unchangeable measures and is often measuring really large scale topics that aren't even really properly sure even 1) exists 2) if it is genuinely even a single thing or an emergent property (as in it comes out through the means of many other things interacting but on its own is not really a 'thing').

Because the measures are not (often) hard measures, they are often subject to ambiguity, bias, interpretation, and questions of how valid of a measure it even is (which isn't a "yes or no" thing, because you very very rarely have a perfectly valid measure in psychology - it is a lot more of how much you are willing to accept it as a decent enough of a measure).

Because measures are measuring things we don't even have a firm concept of ("things falling" for gravity VS consciousness??? what??? is??? it???), the very relation of the measure to whatever the researcher is trying to study and how they understand it has to be taken into account as well. (In the research community of DEDICATED researchers on memory (also often considered one of the more harder sciences in the soft science psychology) while starting to get to an agreement on it - can't even agree on what "memory" and "forgetting" is despite it being the heart of their main dedicated study. Read the discussion on decay vs retrieval)

Because of BOTH of those, psychology is almost ALWAYS up for debate within research, professional, and academic environments. There is always something wrong with someone's research design, variable measurement, analysis method, concept validity, or what the hell they are approaching shit with. (for example, some people in the field of memory don't believe you can retrieve repressed memories because there have been numerous studies that shows that in a research lab they could not get any adult and-not-stressed individuals to intentionally forget an elephant and show evidence of recalling it later within implicit, explicit, long term, or short term memory; I'm sure I don't need to explain why while this is "good evidence" and "science", that its fucking STUPID.) Even the best and most backed ideas in psychology - even in the ones that border closer to neuropsychology - are always genuinely up to debate within the research community.

Additionally, when we talk about biology, chemistry, physics, etc we are talking about fields of science that have existed for millennia (arguably biology has been around since humans have had society with people trying to understand the human body and animals around through what can be considered early scientific means) and at worst centuries (modern chemistry which is around the 1700s or 1800s). Psychology (which is also a large group and not a monolith) has only really been making significant scientific advancements in the tail end of the 1800s and mainly in the early 1900s which, when combined with the issue above makes for an entirely different way you have to approach how you talk about "theories". This is just a sheer numbers game in terms of how long some of these theories have been genuinely considered and challenged by more individuals and also by letting the research fields grow properly.

That is all generally speaking in regards to PSYCHOLOGY. If we are talking about developmental psychopathology and clinical psychology (which would probably be the best specific fields to label the claims the ToSD makes) we have to keep in mind that we are operating in a field that has soft measurements, complex and possibly non-existent concepts they are measuring, and - if we are being real - people who actually are interested in helping and caring for mentally ill people rather than putting them in a hell asylum for debatably give or take a century. A good number of the people who started genuinely giving an interest in actually treating and understanding (with good intent) the mind of mentally ill people could still be alive today. Additionally, its a field that compared to other fields is relatively small in the workforce of people interested in exploring it. Then you have to pull it down to the specifications of dissociation and trauma disorders in those areas and you have that even more so + that the concept of "what is DID" is a WHOLE other thing and that one I won't explain on cause I am in the dunning kruger pit of despair of how that works and I refuse to act like I know what the fuck is going on there and am ok staying in my lane until I resume my education and talk to more experienced people in the field with my 5000 questions.

I had something more to say on this but I lost my train of thought and flow of this specific one cause my bird distracted me and I've been sitting here for 5 minutes trying to remember it and I'm just gonna give up on picking up that train of thought because even if I do I think itll be incoherent with what I wrote above - but they are really non-comparable.

They both use the word "theory" in a similar manner, but it's like grabbing an American and a British person and saying "chips" or "football". You will get a "snack probably made potatoes" but you will very likely not get the same thing because you have to take into consideration what subset of english / the culture around the english word "chips". You will get a game where multiple people play against eachother using a ball to get points on a board - but you will absolutely not be able to get an American team of football players and British football players on a field to play a cohesive game against each other because you have to take into consideration what subset of english / the culture around the english word "chips".

You can talk about apples and tomatos like they are fruits, but when you breakdown what a "fruit" is for each of those. Apples are fruits in almost every field afaik. Tomatos - while fruits - are not fruits in more softer / artistic fields like culinary, and that is where you have to understand the context of the field you are specifically talking about to understand that on a professional level you REALLY should not put a tomato into a fruit salad.

You can talk about fish as a concept as something that obviously exists and that there is research obviously there proving that fish are physically there and an existing phenomenon - but you would be laughed at to state that there is hard scientific proof that fish exist JUST as much as there is hard scientific proof that the Class Chordata exists because 1) what the fuck is a "fish" defined as is up to debate 2) there is a lot of evidence that would suggest that trying to group something as a "fish" is hard to do and absurd.

It's an issue of understanding the context of the term "theory" in respect to the field it is in. It's about understanding that while "theories" are both the "same" thing, the practical application and specific interpretations of the term in their respective fields are drastically different even by the people who are studying it for a living. It's an issue of understanding that even within the same field, the subfields have different context and approaches and guidelines for research that has them coming to different conclusion. It's an issue of understanding that one field is trying to understand often intangible and blurry concepts BY DESIGN (as it is impractical to try to understand shit like DID to the atomic level) and another is operating in investigating a harder and more concrete concept.

You can go into physics, chemistry, and biology and there are concepts you will find that no researcher would really question (unless they are in the really innovative end where they go so deep that the specifics of those are questioned). You can't do that for psychology - and for a lot of the things you think you can for psychology - I would probably be willing to bet you that there is a valid research opposition. You can do that even less for developmental psychopathology and clinical psychology, and even less for dissociation and trauma and that is solely because dissociation and trauma research is dependent on other sub fields like memory, consciousness, identity, etc that are SUPER not established. If researchers can't agree what MEMORY and FORGETTING is; if researchers can't agree if CONSCIOUSNESS even EXISTS; if researchers are clueless as to what the fuck identity is and how the brain generates it - then who the fuck are we to say we know fuck all about DID (which requires all three for those combined) to the same level we understand gravity or evolution.

The theory of structural dissociation is far more a practice-orientated theory to help in the practical immediate because currently the field is too young and confused to have a genuine "this is KNOWN scientifically" consensus - and the ToSD works pretty well for practical uses but you have to acknowledge that it only does so by ignoring five bajillion holes and assumptions it has to make to work. It's laughable to compare something that is a practice-focused theory to something that is a hard dedicated 'universal truth' seeking theory like gravity.

(Which is not to say it is invalid or wrong or anything, see the above conversation on validity in psychology, but that you have to take it with a grain of salt understanding that it is assuming things about memory, consciousness, identity, etc that we REALLY don't even know exists; and this is a GOOD and FAIR trade off because the intent is for practicality and treatment for people that are clearly dealing with SOMETHING rather than a genuine question of what does and does not exist because in clinical psychology there is very very little point in trying to prove something exists because the goal is to TREAT and find ways to help people with whatever it is they are dealing with. You are expected to do some handwaves and generalize concepts for the sake of practicality and application, its just that you have to understand that you are choosing to lower its reliability and validity in name of practicality and application)

-Riku

-----

Post cut comments and thoughts / points that came into my head that I wanted to put in but never got the opportunity.

Another thing worth considering, if I told you that for five billion dollars, I needed you to get me a list of every scientist who helped develop and found evidence supporting gravity OR every scientist who helped develop and found evidence supporting ToSD - which would you do? It'd be a fucking pain in the ass because ToSD is decently supported by a number of individuals, but god hell no would I waste my time even trying with gravity. The list would be larger by an order of multitudes.

I always tell my friends that the field of psychological research is literally just professional discourse / syscourse. Everyone is chronically bitching at each other under their breaths and calling each other stupid and nitpicking the other people's small words and arguments in favor of their theory - and the thing is? They ALL are scientifically valid arguments because in psychology we don't know SHIT. In actual psychological research discourse it's a whole bunch of people slamming papers on the table and going "SEE. I'm right" and then someone picking up their paper and going "Actually your [insert type of validity and research design and concept] is stupid lol" and then slamming another study that accounts for it and supports their argument and then the first guy doing it BACK at him. Thats how the field of psychology works and its so fucking funny and amazing and thats what I LOVE about it. Its PROFESSIONAL discourse and some of the people in the field are the most fucking SNARKY and STUBBORN bitches in how they talk about other researcher's opinions in private but do their best to respect them in public and professionally because they DO respect their role and that their approach is still not only scientifically sound, but also invaluable to the accurate development and understanding of the concept at hand. They WANT to be right and to hold onto their opinion because they feel they are right so there is always this stubborn snark - but there is an agreed and shared mutual understanding that we all are just trying to get to the truth of an absurdly complex and possibly not even real topic and that back and forth is VITAL lifeblood to it.

In regards to #2, its one of the reasons I try to avoid any serious syscourse cause every time I see people saying things are "science" they are usually jsut throwing one psychological research paper or literature review down (maybe 5 if they are actually better at discussing it) and saying "these are FACTS" when - in the field of psychology and research - that is honestly only slightly better than just linking someone else's blog post as evidence. Yeah its more professional and actually based on data and research so its better than someone just saying "its real" but its hardly "facts" like people like to act like they are

This isn't a black and white issue where it either "is facts" or it is "invalid and non scientific" which is the main thing I really want to make sure is clear. We are NOT anti-ToSD but we are anti-"calling things facts when they arent". ToSD is the best that we know currently and it is incredibly helpful in reflecting generalized understandings of a vague concept and we can talk about things in "mosts" and "currently" but we absolutely can't be sitting here stating anything in absolutes because when people say "it just a theory" in THIS case, they are honestly probably more right than wrong because unlike gravity and evolution, ToSD does not have nearly enough support to live up to the standards and comparison of Gravity and Evolution - which is not bad or wrong - it's by design and serves its purpose, it just isn't made to be used Like That.

#alter: riku#research posting#nerd posting#scientific literacy#ask#asks#syscourse#discourse#syscourse tw#discourse tw#riku rambles#tosd#theory of structural dissociation#long post#research

2 notes

·

View notes