#the difference isn't that he's become personable in this social context; he's not! but he's doing his best now

Text

Darcy's role in P&P would work for me anyway, but tbh it works for me 10x better because he halfway reverts back to form towards the end of the book.

#so many takes on darcy seem to think his presentation of himself at pemberley is a permanent radical transformation of his personality#and the end point of his character arc#and it's explicitly not a static end point in that way#his inwards change is real but how much that translates into outwards presentation depends on the context#like late-novel darcy trying to compliment mrs bennet and doing it in a way that reads as icy and brusque is just peak darcy#the difference isn't that he's become personable in this social context; he's not! but he's doing his best now#and this being an ongoing struggle at which he sometimes comically fails is so much more austen#than the total transformation into a perfect dreamboat narrative#but yeah i love that austen goes out of her way at the end to yank him out of his fulfillment enclosures and underscores his foibles#anghraine babbles#austen blogging#austen fanwank#lady anne blogging#fitzwilliam darcy

214 notes

·

View notes

Text

On the Identity of "Chat"

Like all the linguistics folks on Tumblr, I've been sent the "chat is a fourth person pronoun" post by a bunch of well-meaning people and and I've been thinking waaay too much about it. @hbmmaster made a wonderful post explaining exactly why "chat" ISN'T a fourth person pronoun, and after reading it I wanted to go a little deeper on what it might actually be doing linguistically, because it is a really interesting phenomenon. Here's a little proposal on what might be going on, with the caveat that it's not backed up by a sociolinguistic survey (which would be fun but more than I could throw together this morning).

On Pronouns

Studying linguistics has been really beneficial for me because understanding that language is constantly changing helped me to become comfortable with using they/them pronouns for myself. I've since done a decent amount of work with pronouns, and here are some basic ideas.

A basic substitution test shows that "chat" is not syntactically a pronoun: it can't be replaced with a pronoun in a sentence.

"Chat, what do we think about that?"

"He*, what do we think about that?" (* = ungrammatical, a native speaker of English would think it sounds wrong)

Linguists identify pronouns as bundles of features identifying the speaker, addressee, and/or someone outside the current discourse. So, a first person pronoun refers to the speaker, a second person pronoun refers to the addressee, and a third person pronoun refers to someone who is neither the speaker nor the addressee (but who is still known to the speaker and addressee). This configuration doesn't leave a lot of room for a "fourth" person. But the intuition people have that "chat" refers to something external to the discourse is worth exploring.

Hypothesis 1: Chat is a fourth-person pronoun.

We've knocked this one right out.

Hypothesis 2: Chat is an address term.

So what's an address term? These are words like "dude, bro, girl, sir" that we use to talk to people. In the original context where "chat" appears - streamers addressing their viewers - it is absolutely an address term. We can easily replace "chat" with any of these address terms in the example sentence above. It's clear that the speaker is referring to a specific group (viewers) who are observing and commenting on (but not fully participating in) the discourse of the stream. The distinction between OBSERVATION and PARTICIPATION is a secret tool that will come in handy later.

But when a student in a classroom says "wow chat, I hate this," is that student referring to their peers as a chat? In other words, is the student expecting any sort of participation or observation by the other students of their utterance? Could "chat" be replaced with "guys" in this instance and retain its nuance? My intuition as a zillenial (which could be way off, please drop your intuitions in the comments) is that the relationship between a streamer and chat is not exactly what the speaker in this case expects out of their peers. Which brings me to...

Hypothesis 3: chat is a stylistic index.

What's an index in linguistics? To put it very simply, it's anything that has acquired a social meaning based on the context in which it's said. In its original streaming context, it's an address term. But it can be used in contexts where there is not a chat, or even any group of people that could be abstracted into being a chat. Instead, people use this linguistic structure to explicitly mimic the style which streamers use.

And that much seems obvious, right? Of course people are mimicking streamers. It doesn't take a graduate degree to figure that out. What's interesting to me is why people choose to employ streaming language in certain scenarios. How is it different from the same sentence, minus the streamer style?

This all comes down to the indexicality, or social meaning, of streamer speak. This is where I ask you all to take over: what sorts of attitudes and qualities do you associate with that kind of person and that kind of speech? I think it has to do with (here it comes!) the PARTICIPANT/OBSERVER distinction. By framing speech as having observers, a speaker takes on the persona of someone who is observed - a self-styled celebrity. To use "chat" is to position oneself as a celebrity, and in some cases even to mock the notion of such a position. We can see a logical path from how streamers use "chat" as an address term to how it is co-opted to reference streamer culture and that celebrity/observer relationship in non-streaming mediated discourse. If we think about it that way, then it's easy to see why the "fourth person pronoun" post is so appealing. It highlights a discourse relationship that is being invoked wherein "chat" is not a group but a style.

1K notes

·

View notes

Note

from a non-academic, i find parts of comphet to be useful (heterosexuality becomes compulsory when you’re raised in a heterosexual society) but the foundations . suck. what do we do with theories like this, that have touched on a truth but also carry a lot of garbage? can we separate the truth from the founder?

i have to be slightly pedantic and say that i don't think rich's essay is an example of this phenomenon. my central issue with her formulation is its bioessentialist assumptions about human sex and therefore also sexuality. if i say "capitalism includes economic mechanisms that enforce heterosexual behaviour and exclude other possibilities", then what i mean by "heterosexual" is plainly not the same as what rich means—and for this reason i would seldom formulate the statement this way, without clarifying that i am talking about the enforcement of heterosexuality as a part of the creation and defence of sex/gender categories themselves. so rich and i do not actually agree on the very fundamental premises of this paper! rich was not the first or only person to point out that economic mechanisms as well as resultant social norms enforce heterosexual pairings; i actually don't even think the essay does a very clear job of interrogating the relationship between labour, economy, and the creation of sex/gender; she means something different and essentialist to what i mean by sex and sexuality; and i think her proposed responses to the phenomenon she identifies as 'compulsory heterosexuality' are uninteresting because they mainly propose psychological answers to a problem arising from conditions of political economy. so, in regards to this specific paper, i am actually totally comfortable just saying that it's not a useful formulation, and i don't feel a need to rescue elements of it.

in general, i do know what you're talking about, and i think there's a false dichotomy here: as though we must either discard an idea entirely if it has elements we dislike, or we accept it on the condition that we can plausibly claim these elements and their author are irrelevant. these are not comprehensive options. instead, i would posit that every theory, hypothesis, or idea is laden with context, including values held and assumptions made by their progenitors. the point is not to find a mythical 'objective' truth unburdened by human bias or mistakes; this is impossible. instead, i think we need to take seriously the elements of an idea that we object to. why are they there? what sorts of assumptions or arguments motivate them, and are those actually separable from whatever we like in the idea? if so, can we be clear about which aspects of the theory are still useful or applicable, and where it is that the objectionable elements arise? and if we can identify these points, then what might we propose instead? this is all much more useful, imo, than either waiting for a perfect morally unimpeachable theory or trying to 'accept' a theory without grappling with its origins (political, social, intellectual).

a recent example that you might find interesting as a kind of case study is j lorand matory's book the fetish revisited, which argues that the 'fetish' concept in freud's and marx's work drew from their respective understandings of afro-atlantic gods. in other words, when marx said capitalists "fetishise" commodities or freud spoke about sexual "fetishism", they were each claiming that viewing an object as agentive, meaning-laden in itself (ie, devoid of the context of human meaning-making as a social and political activity) was comparable to 'primitive' and delusory religious practices.

matory's point here isn't that we should reject marx's entire contribution to political economy because he was racist, nor is it that we can somehow accept parts of what marx said by just excising any racist bits. rather, matory asks us to grapple seriously with the role that marx's anthropologically inflected racism plays in his ideas, and what limitations it imposes on them. why is it that marx could identify the commodity as being discursively abstracted and 'fetishised', but did not apply this understanding to other ideas and objects in a consistent way? and how is his understanding of this process of 'fetishisation' shaped by his beliefs about afro-atlantic peoples, and their 'intelligence' or civilisational achievements in comparison to northwestern europeans'? by this critique matory is able to nuance the fetish concept, and to argue that marx's formulation of it was both reductive and inconsistently applied (analogously to how freud viewed only some sexuality as 'fetishistic'). it is true in some sense that capital and the commodity are reified and abstracted in a manner comparable to the creation of a metaphysical entity, but what we get from matory is both a better, more nuanced understanding of this process of meaning-making (incl. a challenge to the racist idea of afro-atlantic gods as simply a result of inferior intelligence or cultural development), and the critical point that if this is fetishism, then we must understand a lot more human discourse and activity as hinging on fetishisation.

the answer of what we do with the shitty or poorly formulated parts of a theory won't always be the same, obviously; this is a dialogue we probably need to have (and then have again) every time we evaluate an idea or theory. but i hope this gives you some jumping-off points to consider, and an idea of what it might look like to grapple with ideas as things inherently shaped by people—and our biases and assumptions and failings—without assuming that means we can or should just discard them any time those failings show through. the point is not to waste time trying to find something objective, but to understand the subjective in its context and with its strengths and limitations, and then to decide from there what use we can or should make of it.

541 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Importance of Amae in My Personal Weatherman

Masterlist || Language Analysis Part 1

I have seen a lot of discourse in the English-speaking fandom surrounding Segasaki's apparent dismissal or trivializing of Yoh's desire to pursue his manga, and most of it is negative. His comments about wanting Yoh to remain dependent on him, or that Yoh does not need to earn money are seen as patronizing or controlling at best and oppressive at worst. It appears that Segasaki does not understand nor respect Yoh's need for independence, and that is what strains their relationship.

But what if I asked you to consider that Segasaki's behaviour is actually an invitation to Yoh to reinforce their relationship? And what if I told you that Yoh's withdrawal from Segasaki constitutes a rejection of that invitation, and it is that rejection that strains their relationship instead?

Of course, the end result is the same - a strained relationship - and in reality there is never one side wholly responsible for this. The point of this is to simply challenge the cultural notion that a successful relationship is the coming together of two equally independent individuals, as opposed to the co-creation of a relationship formed by two interdependent individuals.

"If only you could stay drunk forever..."

"It's okay to feel down again for me too you know"

- Segasaki, Ep 4, Ep 5

This isn't about Segasaki wanting to keep Yoh is helpless and dependent on him, but about wanting Yoh to be able to be true to his feelings and express his own desire for affection honestly, without having to hide behind "I hate you" or rejection.

Or, let's try and talk about how Segasaki and Yoh reinforce their relationship through the use of amae (featuring a brief mention of tatemae/honne) who am I kidding this is not brief at all

First: Cultural Context

The way people conceptualize and make meaning of the Self differs between Western and East Asian cultures, and this plays into the differences we see in the basis for our self-esteem, the personal attributes that we value, and even what constitutes the behavior of a mature individual. Broadly speaking, Western cultures tend towards the Independent Self Construal (whereby the Self is a distinct entity separate from others) whereas East Asian cultures tend towards Interdependent Self-Construal (whereby the Self is connected to and defined by relationships with others). Thus, in the West, expressing one's individuality is very important for one's self-esteem, and being able to communicate clearly and confidently is valued and a sign of maturity. Conversely, in the East, one's ability to integrate and become a member of the group is prized, and contributes significantly to one's self esteem. In order to be seen as a mature individual, one must learn not only to read a social situation but also how to modify one's behavior in order to respond to the changing demands of that situation, with the ultimate goal being to maintain group harmony.

tl;dr - In East Asian culture, behaviors and attitudes that emphasize interdependence and promote group harmony actually play a big role in reinforcing relationships and one's membership towards the group.

Segasaki is an expert at this - his "public mode" that Yoh refers to actually shows us how good he is at social interactions. This is the Japanese concept of tatemae/honne (crudely translated as public self/private feelings) - which I could link to a bunch of articles for you, but I'm going to suggest you check out this 9 min street interview instead. At 6:41, one of the interviewees comments that another is sunao, or "honest" (we'll cover this later too) and at 6:49 specifically talks about how reading situations is important as an adult. Segasaki reads the room well, but most importantly, he reads Yoh well.

Yoh is not good at this, at all. In Ep 6, we see that he does not integrate well with the group, and he doesn't realize how he might appear to others when he stares and sketches from afar. Yoh does not read the room well because he doesn't pick up on social cues and does not adhere to social norms (I'll point these out in Ep 6's corrections). He cannot read Segasaki, and especially cannot read Segasaki's amae, or his attempts at reinforcing their relationship. Part of this is because his low self-esteem causes him to withdraw from Segasaki's affection as a means of self-protection, and so he valiantly tries to deny his feelings for Segasaki. As Man-san commented in Ep 4, Yoh is not sunao - he has difficulty with being true/honest about his feelings, even to himself.

Sunao is another term that usually pops up when talking about feelings/relationships. It can be used to describe one's relationship with oneself, as well as the relationship with another/group. With oneself, it is usually used to mean "being honest/truthful/straightforward/frank/open-minded about one's feelings". With another person/group, it is usually used to mean "to cooperate/listen/be obedient, or "to be humble/open-minded". In essence, the word encompasses an ideal virtue that is often taught from early childhood - that we should treat both ourselves and others with humility and honesty, because that is how we accept ourselves and stay in harmony with other. This is what becoming an adult, or gaining maturity, means (not gaining independence, as adulthood is often equated to in the West - do you see a running theme here 😂). Of course, that's actually really hard to do, so you'll often hear children (and immature adults too) chided for "not being sunao" (this can therefore sound patronizing if you're not careful). We'll revisit this in a little bit.

Second: What is Amae?

Amae is a key component in Japanese relationships, both intimate and non-intimate. It happens every day, in a variety of different interactions, between a variety of different people. But it is often seen as strange or weird, and those unfamiliar with the concept can feel uncomfortable with it. This stems from the difference in self-construal - because independence is tied so strongly to an individual's self-image in the West, it is very hard to fathom why behavior that emphasizes interdependence could be looked upon favorably. It is telling that every possible English translation of the word "amae" carries a negative connotation, when in Japanese it can be both negative or positive. The original subtitles translated it as "clingy", for example. Other common translations include "dependence", "to act like a child/infant", "to act helpless", "to act spoiled", "coquettish", "seeking indulgence", "being naive" etc.

From A Multifaceted View of the Concept of Amae: Reconsidering the Indigenous Japanese Concept of Relatedness by Kazuko Y Behrens

*Note - the word "presumed" or "presumption" or "expectation" or "assumption" used in the above definition and in the rest of this post, can give the impression that all of amae is premeditated, which adds a calculative component to this concept. Whilst amae can indeed be used in a manipulative manner (benign or otherwise), it is not the case for every single situation, and often amae that seeks affection is often spontaneous and without thought, precisely because the situation allows for it to appear organically. This is the amae that Segasaki and Yoh most often exchange - so think of these assumptions and expectations as "unconscious/subconscious" thought processes.

Third: Amae Between Segasaki and Yoh

Yoh shows a lot of amae when he is drunk:

He whines, buries himself into Segasaki's embrace, refuses to move or let go of him, and keeps repeating "no". In these interactions, Yoh wants Segasaki's affection, but instead of asking, he does, well, this, and he presumes that Segasaki will indulge his behavior. Leaving to get some fresh air might not be as obvious - but it is a form of amae as well, because Man-san is his guest, not Segasaki's, and he shouldn't be leaving Segasaki to entertain her. The expectation that this is okay, and that neither of them will fault him for it, is what makes it amae.

Segasaki obviously enjoys indulging Yoh when Yoh does amae, because he recognises this as Yoh's request for affection from him. It's not that Segasaki enjoys Yoh in this drunk, helpless state; it's not even that Segasaki feels reassured by Yoh's requests for affection. Segasaki knows Yoh likes him, and recognizes that Yoh is struggling with those feelings. That Yoh is actually able to do amae to Segasaki is what delights him the most, because it is something that requires a lot of trust in Segasaki and a willingness to be vulnerable in front of him. This is how amae reinforces relationships - when a request for amae is granted, both the giver and the receiver experience pleasant feelings.

That said, an amae request can also be perceived negatively - if amae is excessive, or if the person responding feels they are obligated to do so. In Ep 5, Man-san chides Yoh for his amae - the fact that he expected to do well from the beginning, and became upset when he failed. He told her about his unemployment, presuming that she would comfort him, but alas.

Segasaki also does amae - but unfortunately Yoh misses many of his cues, and so neither of them really gain pleasant feelings from the interaction (ok so maybe Segasaki does, but I will argue that is more because Segasaki also enjoys it when Yoh obeys him - see @lutawolf's posts for the D/s perspective on this!).

Did you catch it? Segasaki wants Yoh to pass him the Soy Sauce, which, clearly, he is capable of getting himself. He tells Yoh to feed him, because he wants Yoh's affection. And the real kicker - he asked for curry, and expected Yoh to know he wanted pork. In all these interactions, Segasaki presumes that Yoh will indulge him and do for him things he can do himself perfectly well (and even better at that) - this is what makes this amae. But look at Yoh's reactions:

Yoh just stares between the Soy Sauce and Segasaki, between Segasaki and his food, and then just at Segasaki himself. He doesn't recognise any of this as amae, and in the case of feeding Segasaki makes the conclusion that this is somehow a new slave duty he's acquired. And therefore, he does not gain pleasant feelings from it.

In Ep 3 we see a turning point in Yoh's behaviour - his first (sober) attempt at amae (the argument in Ep 2 is debatable - it's not amae from Yoh's POV, but Segasaki responds as if it were, with a head pat and a "when you get drunk, you talk a lot don't you?").

Here, Yoh wants to express his desire for Segasaki's affection, but he can't bring himself to say it aloud. Instead, he dumps bedsheets on Segasaki's lap, as if the bigger the scene he makes the greater the intensity of his desire he can convey. It is the presumption that Segasaki will understand him that makes this amae. And then, we get this:

Not only a happy Segasaki and a sweetly shy Yoh, but also a Yoh who's emboldened by Segasaki's response, and who finally, for the first time, reciprocates touch, and considers the possibility that Segasaki might actually like him.

With every episode, Yoh gets more and more comfortable with doing amae towards Segasaki, because Segasaki picks up on his cues and always responds to them. In Ep 5, Yoh's amae comes out naturally, triggered by the stress of his unemployment, and we see it in all those moments he sounds and acts like a child, and as I mentioned, Segasaki spends the whole episode reassuring Yoh that his amae is welcomed, and that Segasaki likes responding to it. If you've been wondering why the relationship between Segasaki and Yoh can, at times, feel somewhat parental in nature - this is it. It's because Segasaki sees the contradiction between Yoh's childlike insistence that he does not like Segasaki and his desire for Segasaki's attention and affection, for what it really is - Yoh's struggle with accepting himself. When Yoh is able to be sunao, he does amae naturally, and Segasaki responds to him in kind.

Now, all we need is for Yoh to recognize when Segasaki does amae, which will likely happen soon, given that Yoh has grown with every episode.

As always, thank you for reading :))

#my personal weatherman#taikan yohou#体感予報#segasaki x yoh#MPW language analysis#sociolinguistics#japanese language#japanese cultural tidbits#mytranslations#MPW subtitle corrections#my meta is creeping into my sub corrections#need to get it out here instead#sorry for the length#tbh posting such crazy long posts and expecting that people will actually read it#can be considered amae too 🤣🤣#Ep 6 corrections will be out next#I just needed to get this out before 7#and i sorta made it

433 notes

·

View notes

Text

Adventure Time has the best redemption arcs

I love deep-diving into my favourite shows, which makes me lucky that Adventure Time has been analyzed to death.

It's awesome because it feels like the show itself is growing up along with Finn. The older seasons are a lot more episodic and focused on the surreality of Ooo. Meanwhile, the later seasons really embrace the show's complicated lore and the idea that morality isn't black and white. The progression of maturity in this one show is INSANE. As the show becomes more mature, so does main character Finn, physically and emotionally.

Nowhere are the show's themes and Finn's personal growth better demonstrated through the show's use of redemption arcs. As the show progresses, classical villain-hero archetypes are subverted to show that Finn is learning that people aren't exclusively good or bad. As the show and Finna age, being a hero or doing the right thing evolves from the basic idea of "fighting evil" to being empathetic and seeking peace.

Heavy spoilers for the main series after the cut.

Some context

I just wanna mention some facts about the show's history.

If you watch the first AT episode followed by the last episode, you're gonna feel disoriented. They're clearly the same show, but it feels like they have very different goals. Early AT is more lighthearted and less serious. The episodes have morals, but they're pretty simple. The randomness of Ooo is played more for comedy than for lore purposes.

Around season 5, the show started taking on a different direction. It's still funny and weird, but the characters are more fleshed out and the messages the show is trying to convey require a lot of digestion. For example, Princess Bubblegum is always smart, but the way she's depicted in episodes like"Enchiridion" vs "Burning Low." Although I consider this a massive improvement, it's unclear how much was pre-planned. Was PB always destined to become a control-obsessed, unethical ruler-scientist? Or was her initial characterization just Finn's crush?

Yes.

Episodes as early as season 1 ep 24 ("What have you done?") show PB acting more like a tyrant than a princess and have the Ice King depicted in a less antagonistic matter. The reason for the tonal shift in the later season is that as Finn grows up, his experiences change the way he perceives reality.

Ooo through Finn's eyes

Adventure Time is about Finn the human and Jake the dog, but really it's mostly about Finn.

The other characters get character arcs and have plot-relevant conflicts, but the show's main focus is dedicated to Finn's coming-of-age story. Finn is Ooo's hero: he's social, caring, and brave, and he's motivated by a strong sense of justice and a desire for adventure. All he wants is to try new things and help others at any cost.

However, he's only 12, at least at the beginning. His idea of being a hero is rooted in black/white morality. If you do bad things, then you're bad. Stopping bad people makes you good. And as a 12-year-old, he believes the only way to stop bad people is through violence.

The show is immature in this respect, too. For the first few seasons, there are two main antagonists. There's the recurring Ice King and his plots to force princesses to marry him, playing off the "save the princess" trope (more on him later). And then there's the Lich, who's a genuinely powerful cosmic entity that seeks to destroy life in all its forms. Naturally, Finn fights them both off through righteous punching.

The show presents this basic understanding of evil, that evil is as evil does. In the beginning, there's almost no nuance to these characters. And this is true with good characters, too.

Billy is a huge catalyst for Finn's character development, but you can see the show's limited understanding of heroism in his debut episode. Billy is Finn's predecessor in a way, being the number one fighter against evil. In "His Hero," Billy realized the fighting evil through violence didn't treat the root problem, opting instead for community activism. However, the show makes this look like a bad thing, with the moral of the episode being that violence can solve problems. Ironically, Finn's character development mirrors Billy, as he realizes over time that he fighting evil might mean hurting people he cares about. Case in point: Simon Petrikov, the Ice King.

The power of redemption arcs

Redemption arcs are controversial because they're ideal but they feel forced if they go unearned. In Adventure Time, redemption arcs serve a two-fold purpose: to convey the message that "evil" people can be understood and rehabilitated and to show Finn's developing maturity as he realizes this.

Ice King

The first character to get a real redemption arc is the Ice King. Initially, he's portrayed as Jake and Finn's natural nemesis, especially when he targets Princess Bubblegum. However, as the show goes on, it becomes clear that the Ice King isn't really malicious; he's just lonely and he doesn't know how to socialize in an appropriate way. Over time, he becomes a sympathetic villain. However, this changes with the Christmas specials "Holly Jolly Secrets, parts 1 and 2." In this episode, Finn and Jake discover the Ice King used to be a man named Simon, whose personality and sanity were corrupted by magic. Simon's backstory is further developed in "I Remember You" and "Simon and Marcy." From this point on, Finn starts referring to the Ice King as Simon, acknowledging Simon's true self and stops treating him less harshly. This leads to a really heartwarming moment in "Don't Look," where Finn's perception literally warps reality, causing the IK to revert to Simon (in appearance but not in personality).

Consequently, the Ice King becomes less antagonistic in general and we even get IK-centric episodes where he takes on a heroic role. For all intents and purposes, post-season 3 Ice King is Finn's friend. The show went from using a cliché villain-type to dedicating a significant amount of time and plot to Ice King's eventual return as Simon. From this, Finn learns that treating people with kindness is imperative to stopping evil. Not only did finding out that IK's personal life was tragic but by treating him as a friend he diminished IK's evil inclinations.

Magic Man

Magic Man is one of the more disturbing characters on the show. He always shows up to do something gross or psychologically messed up. Unlike the Ice King, who was shown to be evil because he wanted companionship, Magic Man wants people to suffer out of pure contempt for the world. His "pranks" include simple stuff like turning Finn into a foot, to more deranged acts like forcing Jake to escape a dream world where doing so would mean destroying all his new friends.

What's interesting about Magic Man's redemption arc is that Finn and Jake have little to do with it. Magic Man redeems himself practically by accident.

We gradually learn that Magic Man's wife was destroyed by GOLB, a powerful entity that can erase things from all realities. So Magic Man's cruelty is best described as frustration or vengeance to an extent. He is constantly suffering, which he tries to mitigate by deriving pleasure from others' suffering.

However, he eventually loses his magic powers (and with it, his anger and sadness) in"You Forgot Your Floaties", grounding him back in reality. From then on, his journey is one of atonement. He tries to reconcile with his family and seeks forgiveness from the people he has tortured.

This arc says more about the show's maturity than it does about Finn's. Although Finn shows no hatred towards a magic-less Normal Man, he seems pretty indifferent. The show, on the other hand, takes the time to make him a tragic figure and offers him a chance at redemption. It wants the audience to know that experiencing loss is not an excuse for being a jerk, but it can explain someone's actions.

King Man's (his title after rejoining the Martian community) redemption arc also demonstrates AT's advancing writing skills. Instead of giving King Man a clear-cut redemption arc, the show depicts him as genuinely sorry without changing his personality. King Man is still obsessed with Margles and is harsh with Martian prisoners, but he's no longer angry with the world. He hasn't moved, as is difficult to do with grief, but he wants to contribute to society instead of rage against it.

Betty Grof

Betty marks a milestone in the show and Finn's personal growth. She is the first antagonist who is shown to be sympathetic from the start. It helps that we know Betty before she goes crazy with magic, but despite that, Finn nor the show ever thinks of Betty as an "evil" character. She's misguided and unethical but well-intentioned.

Betty's whole deal is that she wants to be with Simon, which requires curing him of the Ice King Crown's effects. However, after she absorbs Magic Man's madness and sadness, she starts undertaking strategies that cause Ice King more stress than good.

She becomes a true antagonist in the Elemental mini-series when she prioritizes Simon's recovery over the lives of Ooo's inhabitants, despite the Ice King begging her to save his friends. Even after she betrays Finn, he doesn't seem to see her as a villain specifically. The real source of conflict in the Elemental series was more so the unchecked emotions of Finn's friends; Betty was just an obstacle.

Betty's redemption arc is completed in the show's finale. Betty summons GOLB, risking the entire universe's destruction to save Simon. Except her goal is not only to save Simon but to save their relationship. In an act of self-sacrifice, Betty manages to banish/merge with GOLB to save Ooo, despite knowing she could never be with Simon.

However, it's not as clear as I make it out to seem. While Betty does sacrifice her relationship with Simon, she still manages to save him, begging the question: if Betty couldn't save Simon, would she have made that decision? (I'm inclined to think no, but let me know what you think!)

Even if the "redemption" part of her arc feels rushed, it's Betty's journey that highlights the show's maturity. Just because she does bad things doesn't mean she's a bad person. Finn gets this; he doesn't blame Betty for almost destroying the world. He's more focused on aligning with her desire to save Simon and the rest of Ooo.

Through Betty, Adventure Time explains that it's impossible to judge people as good or evil. To do the right thing doesn't mean to help people who you think are "good" or oppose people you think are "evil" but to find common ground and a common goal.

Uncle Gumbald

He's basically the last antagonist of the show. I don't think there's a lot to say about him that hasn't already been said, so this section will be short.

He's a lot like PB in that he's a visionary. Their conflict stems from their competing ideas and the fact that they both want to subjugate each other.

They almost reach an understanding in the finale when they experience each other's lives, with PB realizing that Gumbald deserved to be treated as an equal. However, he isn't redeemed because he attempts to subjugate PB anyways by faking a truce. I feel like this was supposed to highlight PB's character growth as early PB definitely wouldn't have been willing to share authority.

Fern

I would say this is probably the most important redemption arc for Finn's character. It's weird to say that because Fern is introduced so late into the show and his arc is completed when he dies in the last minutes of the finale. Furthermore, he's a strange character to begin with. He's a grass clone of Finn made from two magic swords, and he's hardly antagonistic toward Finn except in the last two seasons.

But let's look at what we're dealing with here.

Fern's internal conflict is an identity crisis. At one point in the series, Finn comes into contact with a past self (merging timelines situation, dw about it), turning one of his selves into a sword. It's intentionally ambiguous at first, but it's eventually revealed that there is a miniature Finn inside the sword who is cognisant of the world around him. Because of Real Finn's carelessness, Sword Finn ends up getting busted, and eventually infected with a grass parasite, creating Fern.

Up until now, Finn has been acing his new pacifist approach to conflict resolution. He now prioritizes understanding someone's actions and reasoning with them, saving fighting as a last resort.

Fern represents Finn's greatest empathy challenge: trying to understand someone he thinks he already understands. To do this, Finn has to accept that his preconceived notions of Fern are wrong and take the time to get to know the real Fern. He thinks that because they share some sort of biology and memories, they are the same people. He fails to acknowledge the different life experiences that have forged him and Fern into distinct people.

When Fern heel-turns into an antagonist, it's not a surprise. We have seen repeatedly the jealousy that he feels outcasted by the real Finn. We also know he's frustrated with the dissonance between his past "life" and his current circumstances. Like Betty, Finn doesn't see Fern as a villain. However, he doesn't try to understand where Fern is coming from. He assumes that because they are similar, Fern will be willing to talk things out. In other words, Finn wants to reconcile with Fern but doesn't get how devastating Fern's identity crisis is.

In the finale's dream-dimension fight sequence, we see Finn finally hear out Fern's concerns and the two explore Fern's past together.

Fern does die because of plot reasons, but not before re-establishing his and Finn's friendship. I don't really like it when stories sacrifice one character for another's development, but it makes sense given Finn's narrative is about realizing that doing the right thing isn't always a feel-good experience. Finn wants the people he cares about to be safe, and he knows that Fern is in danger by siding with malicious characters like Gumbald. Fern also decides to align with people who care about him rather than someone who wants to use him. If Fern's villain arc is caused by feelings of inadequacies, then it's resolved through self-acceptance. Redeeming Fern requires Finn to truly understand Fern, but this means Finn loses someone who gets him.

I think it's implied Fern could never be at peace alive, since the grass demon was keeping him alive while corrupting his heart. It's a unique take on a heroic sacrifice: setting Fern free means letting Fern go.

Misc. thoughts

Not all redemption arcs are equal. I wanted to touch on a few mini-redemption arcs that either didn't fit the post or had a lesser impact on the story. These aren't relevant to the text, so feel free to skip to the conclusion.

Irredeemable villains

Some AT antagonists never get redemption arcs. These are usually one-off villains who don't get much characterization apart from just being evil. I don't think that AT wants to imply these people are beyond help (see Magic Man for proof), but maybe becoming a good person means that someone has to understand you first, which is harder to do in some cases. Examples include:

Ricardio the heart man

Thief Princess

Wyatt

Redemption arcs?

Originally, I wanted to write a section on Princess Bubblegum and how she gradually releases her iron grip on her kingdom. However, I decided against it because Finn never really sees her as a bad person. However, understanding that she's not perfect is definitely part of her arc. If I were to write about PB, it'd have to be a separate article, probably incorporating how Marceline plays into her character development and how her relationship with evolves over time.

Another character I omitted from this analysis was Lemongrab. I wouldn't describe his arc as a redemption arc because I feel it was more focused on self-discovery than making up for his past actions.

Finally, I thought about writing about the Lich's transformation into Sweet Pea, but I almost don't count it since they are essentially two different characters. A redemption arc to me means that a character undergoes a change of heart. I feel like Sweet Pea is more like the Lich reborn, and while you can argue that the events in "Whispers" are the good Lich fighting against his dormant persona, I feel like it's clear that Sweet Pea and the Lich are not one and the same. Either way, Sweet Pea being the Lich's redemption is to muddy to discuss in this context.

Becoming good

One thing I like about Adventure Time is that no one tries to make the bad guys turn good. Redemption arcs are mostly self-initiated. With characters like Ice King, Finn doesn't try to turn him into a hero, he just stops treating Simon like a villain. Unlike in other media, heroes and villains are not real roles in AT. They are more like social constructs that are easily altered once you start to empathize with supposed villains.

But while "villains" is a flexible term in AT, evil-doing is not. AT puts forward the standard that people should seek forgiveness and atone for the ways they've caused harm. It's a pretty grown-up idea that we should own up to our actions but also forgive people who want to be forgiven.

Conclusion

In Adventure Time, Finn wants to be a hero, but in trying to do so, he needs to answer this question: "What makes a hero?" Originally, the show asserts that a hero is someone who beats up bad guys and obeys people in authority. But as Finn and the audience get older, the show's ideas evolve, too. Through the use of its extensive rogue gallery, Adventure Time affirms that "bad people" are usually just normal people with personal issues. Heroism becomes less associated with righteous violence and more geared towards empathy and reconciliation. Eventually, Finn and the show give up on the hero-villain dichotomy, acknowledging that these categorizations prevent people from helping those who need it most.

Note: this is the first analysis I've posted on Tumblr and I'm planning on writing more with the goal of getting better at writing and media literacy. Additionally, I really love this franchise and I'm always down to discuss it further. Please let me know what you all think?

#adventure time#adventure time analysis#tv analysis#cartoon network#finn mertens#finn and jake#princess bubblegum#ice king#magic man#betty grof#fern#uncle gumbald#golb#the lich

267 notes

·

View notes

Text

imo part of contemporary racist attitudes (from any side of the political spectrum tbh) towards east asia are a lineage from older orientalist beliefs that easia (particularly china and japan) is ancient and unchanging. orientalists of the 19th century saw our countries as places that were stuck in time, decaying through inertia and opposition to "progress" (which, of course, would be brought to them by opening themselves to the west).

modern-day east asia... enthusiasts [polite smile] i'd argue cultivate a descendent of that thought. those who don't assume easia is just like their home country instead treat easia like it's insular from history and the rest of the world, as though our countries have not been historically imperialised and are not bombarded (like the rest of the world) with western viewpoints and american mass media. as though we don't go through societal change through our own efforts and of our own accord.

but no - east asia is a holdout against the tide of modernity. culture is not the background and context against which we move, but traits of each individual's character. an unruly child isn't just upset because his parents aren't buying him candy, he is rebelling against confucianism, and his parents disciplining him is bringing him back in line with confucian teachings. we are defined by rules, philosophy, and tradition—the more ancient these things are, the more intriguing for our onlookers.

better yet, to be untouched by modernity is to be untouched by its discourses. you know, "japanese people don't care about political correctness, they just write what they want" and "actual japanese women don't mind being sexually harassed" and "japan is homogenous so you can't possibly expect them to be sensitive towards other races." japan is presented as static and unchanging—people don't care because this is how things always were, and this is how things will be forever. it's their tradition. it's their culture.

meanwhile china's rapid societal modernization post wwii is largely regarded in every aspect to have been brutal and barbaric. whether change yields positive or negative results it's viewed negatively, as though it doesn't matter how many years pass or how many steps are taken, chinese people are still backwards and regressive, always socially lagging behind the west. because that is apparently our culture.

and yes this comes from all sides of the political spectrum. the right-wing fanbase which idealizes the unchanging nature of japan, a "progressive" fanbase that assumes japanese people are so tied to tradition and an imagined culture that everything goes back to rigidity and long-established practices, often justifying harmful things in the name of respecting japanese culture. nothing and no one in china can't be explained by saving face and confucianism, which is at all times oppressive, evil, and a source of mystical guidance for chinese people.

being considerate and acknowledging that you might not immediately understand every cultural nuance is good, acknowledging that not every story needs to be personally relatable is good, acknowledging that people are influenced by cultures different from your own is good. but at some point it becomes ignoring the fact that asians are humans who are influenced by our culture in addition to personal experiences, feelings, traumas, ambitions, politics. like just think about how everyone around you interacts with culture and to what degree that informs their actual personality and deepest desires and assume that asians are the same as you in that respect please.

being an asian among easia "enthusiasts" is like there's always this interminable search for authenticity, for what is "traditional," for the "real" japan untarnished by these modern western ideas of feminism, and meanwhile many societal advancements for china are just... ignored (don't you know regressive china is so homophobic that disney can't even portray gay affection?). everyone wants to pull us back through time and explain us through adherence to culture and tradition, as though the modern day and just... simple human experiences don't matter or contribute to our lives. we just gotta be explained by something else, something that makes us other from the west.

166 notes

·

View notes

Note

ooh you should elaborate ooh

( @oklotea ) ( @dollmenace )

why ofc 🤭 with no further ado here are my transfem headcanons & explanations

duchess :

manifesto largely here , here , and here , but I don't ever clarify as to WHY I think she has trans girl energy, so I will elaborate now.

first of all, narrative role of swans in stories. especially in stories like the ugly duckling, where there's an "ugly" kid who is socially outcast, excluded, harassed, and ends up becoming something beautiful like they were always meant to be-- it works really well as a trans metaphor, and duchess is literally a swan <3

but that's not her story! and you'd be right to point that out. to me, there's something about the way she's constantly feeling left out of the other princess groups because she's not a "happily-ever-after princess," the way she's basically dismissed by the princessology teacher by her saying "are you sure you're a real princess?" -- and wanting so desperately to be one.

so she follows around ashlynn, so she yells at apple, so she tears raven to shreds. she is so jealous and I honestly really think that the jealousy translates really well to a sort of gender envy -- especially since she's constantly dismissed by the same girls. she's constantly portrayed as wanting to "steal" their stories, and really all she wants is a happily ever after, the same safety and comfort they get by being a princess. I think the metaphor kind of speaks for itself.

"Seems to me we need to win this thing so you can always be a girl." - Sparrow Hood to Duchess Swan, Next Top Villain

dexter :

manifesto here + also I ADORE @tiny-leafbug's transfem dex art

now I know a lot of people headcanon dex as transmasc, which honestly I can actually fully understand in the context of the show and diaries. the idea that he's constantly trying to perform this paragon of masculinity, and constantly falling short. I get it.

HOWEVER! the books is where I fell in love with dex, and in the books dex's vibe is different. he doesn't care about being a "prince charming," not really, and his relationship with his brother seems much more affectionate, with him responding to daring's ribbing in turn and not really caring about daring making fun of him. this lack of caring makes all that pressure put on his shoulders by his parents seem more like something he never wanted to live up to in the first place. on the boxes, he says -- well, I'm good at hero training. and in the books, raven notices the calluses on his hands, the skill he has in PE class. it's not that he's ever been bad at what his parents what him to do. it's that... he doesn't want to do it.

at some point he says "well ... everyone else has been able to recite their story since they learned to talk, while I'm facing this huge unknown." there's something about this lack of direction and destiny that sets him completely apart from students that need to be a certain thing. all dex ever had to do was be a prince, and still, he wants to rebel. still, he followed raven into the dark. because maybe he didn't want to be a prince at all.

raven said "check you out, totally rocking the prince-to-the-rescue gig," and dexter said "what? no, I mean... that's not really me." - Storybook of Legends

dexter, in the books, is constantly torn between the royals and the rebels, this loyalty he has to the first person that's ever seen him, and daring, who still wants him to be, yknow, him. he is expected, at all times, to perform as his brother, to be his brother. and he doesn't want that. he doesn't want that at all.

“And Prince Dexter Charming?” Kitty smiled hugely. Her smile lingered a moment after she disappeared. She reappeared beside Dexter, holding a broom, which she thrust into his hands. “He might become a wicked witch!”

Dexter looked at the broom, shrugged, and gave a small laugh, glancing over at Raven as if to check what she thought.”

- The Unfairest of Them All

cedar :

I don't have quite as much to say here; this isn't a headcanon I have 24/7, it's just fun to think about

she is constantly talking about how she "wants to be a real girl" and idk there is something trans about that. to me.

“I don’t know what to do,” said Cedar. “Am I supposed to sit with my friends same as always? Or pick a side based on what I want? I’m not a Royal, but then again I do want my destiny, when I’ll be changed from a puppet into a real girl, but then again, I do want others to be able to choose if they don’t like their destiny so… so I don’t know what to do now!” - The Unfairest of Them All

I hope this helped <33

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

TLDR; i am more attached to the lost trio than the og trio

i don't know how this happened, but i find the lost trio much more, i don't know, entertaining(?) than the og trio. i also feel like the lost trio has like a counterpart to them in the og trio, so that's how im going to break down this opinion peice.

the first one i'm going to do is piper and annabeth. i chose piper for annabeth because in the books they are shown to be kind of like a direct parallel of each other, so thats my reasoning for piper as annabeth. that, and the only girls in both of their trios. i feel like i became more attached to piper since i got to see things from her perspective, i never really got that sort of thing in the original books. you are going to hear that a lot, but we only ever saw things from percy's perspective, and it was easy to get attached to characters but you were never as attached to them as you were to percy. i feel like we didn't ever get to see much from any other character's perspective, unlike tlh, where we get chapters from the three main characters perspectives. we get to see piper's personal frustration with the aphrodite cabin, or her traitor's guilt about what she's doing. we never got to see this kind of thing from annabeth, we kind of had to go with the social cues percy gave us, not annabeth directly stating. i feel more connected to piper because of how much more we got to see her emotions, and we were never told how she felt from a party that wasn't her.

next, i'll do leo and grover. they aren't a direct parallel like piper and annabeth, but i was originally going to compare jason to grover but their personalities feel too different, at least grover and leo have a little in common. i feel like we didn't see enough of grover to become properly attached. his story felt mostly wrapped up by book 4, and then his final ending in book 5 was like remembering you have leftovers from the night before. and even though he had some sort of cameo in every book, the cameos were always short. like that one family member that shows up to the function, grabs some food and leaves. and, once again, we get proper chapters from leo's view. we never really hear any sort of bad emotions from grover, the few times we did he seemed very general. like when he felt he'd never be as great of a hero as percy, or his fear of not getting his searchers license felt so general they were impersonal in a way. who knows how many demigods felt bad about themselves cause they thought they'd never amount to anything because of percy? or how many satyrs were afraid of not getting their license! were as we see leo dealing with what i assume is some form of survivor's guilt. like feeling that it was entirely his fault his mom died but he survived, it feels so personal. it makes you sympathize with him. i like leo more because of how brief grover is in most of the books.

lastly, jason to percy. they aren't the best parallel, like, at all, but they'll have to suffice. i don't think this is a real thing, but reading so many things from percy pov, i felt almost like a fatigue of reading it. at least with jason we get breaks. and unlike most readers, i actually found jason's perspective more entertaining. i don't know why, though it might have to do wiht the fact that i act a lot more like jason than percy, so there was almost a built-in connection. and percy kind of states the way he feels, and we already know most of what he had gone through, unlike the first ever interaction we have between jason and his past. he talks to lupa, and has this sort of context mental structure. he talks about how he has this feeling he isn't allowed to be weak when talking to lupa, he suppressed his emotion and he doesn't even know he did that. it feels almost like that joke where you say something traumatic under the guise that it's funny, and when they react weirdly you think, that didn't happen to you? jason doesn't even know he was taught to supresss weakness, and does it subconsciously, whereas percy expresses his emotion, even the ones that are weak. we also put percy on a gold pedestal, but jason didn't get that treatment from the fandom, since he was a demigod who felt he was better than the hero we read about first. jason just feels more relatable for the people who felt like they needed to hide anything that made them weak, or the ones who felt shunned by a large group of people. i am more attached to jason because he has subconsciously routed these ideas so deep in his brain, they are still there when hera steals his memories.

overall, i feel like the lost trio is more relatable to me than the og trio.

#essay#essentially just an essay#percy jackon and the olympians#heroes of olympus#pjo hoo toa#pjo#hoo#the lost trio#the og trio#jason grace#leo valdez#piper mclean#percy jackson#grover underwood#annabeth chase#opinion paper#opinion piece#opinion#opinion essay

41 notes

·

View notes

Note

hey its the anon who was asking about achilles’ characterisation in the iliad! thank you so much for your answer, it was super informative and helpful. i think i very much had the wrong interpretation because i had a classics teacher for a year before my school scrapped the subject and they basically rambled about how achilles was a rapist and awful and went against the gods etc. without really going into the nuance of everything or explaining the context of heroes. i was kind of curious about your mention of hubris though? i thought that was a Big Thing in ancient greece because placing yourself on a pedestal above the gods was a guaranteed way to get yourself smote. sorry for acting like a student bugging their favourite teacher for an answer but you really do explain things so well 😅

Hubris is a big thing in ancient greece, you're right; there are so many myths where someone does something stupid and gets their ass whooped by the gods (e.g. Perseus and Andromeda, among many others). But it isn't exclusive to Ancient Greece. In fact, the idea of hubris may have started there, but it changed throughout the years and took different forms in literary tradition. In ancient greek mythos, hubris is usually violent or dangerous behaviours, such as extreme boasting, that are ultimately punished by the gods. In that sense, hubris is external, that means the punishment comes from outside. As cultures changed and the focus shifted more on the individual, hubris started being used to denote a personality quality of excessive pride and arrogance, which are big no-no's in Christianity. So hubris gradually became more of an internal thing, a cautionary tale to make sure the faithful stay humble and are rewarded in the afterlife. In the context of stories, that often comes with personal development of some kind, such as the protagonist seeing the error of their ways and changing their behaviour, which isn't really an integral part of ancient greek mythos as a whole.

Ancient greek hubris and christian hubris often become confused, and because we are taught that hubris is SO important to greek mythos, people try all the time to fit the Homeric works into these neat little boxes. The thing is that Homer does not fit into that; Homer was strange even when the works were written. The Iliad doesn't follow the traditional formulae of stories and myths that were popular at the time, especially oral poetry: it includes emotional change but isn't a story about personal empowerment; there is complexity and nuance in all of the characters but the characters are not idealised; it is a meditation on complex social and human themes such as the connection between rage and grief; it puts mortality, not morality, at the center of the story.

It shows how vulnerable the characters are through their rage or their grief or their passions in general, but the story isn't at all about characters being punished for their hubris or wrong-doings. For example, Agamemnon technically commits hubris in the very first book of the Iliad, when he refuses to give Chryseis back to her father and Apollo gets pissed off about it. This could be considered dangerous behaviour by ancient greek standards, and the Achaeans are indeed punished for it with the plague that Apollo sends their way. However, at the end of the day Agamemnon himself does not get punished for his transgression in any way. He gets everything he wants: Achilles rejoins the fight eventually, Hector is killed, Troy is sacked, he returns to Argos a victor.

Achilles, too, could be said to have committed hubris through excessive violence, when he killed so many people he clogged up the river and then fought the god Scamander himself; and yet he isn't punished by the gods or by the narrative, he is one of the few characters (perhaps the only?) that gets a redemption arc of sorts, by returning Hector's body to Priam and treating the old man with respect, thus showing us his generosity, his integrity, and the nobility of his character once again. And that's where the Iliad ends for him. Not with his death or with him killing even more Trojans or whatever, but with a poignant and moving scene between two people on opposite sides of a war, who have lost everything and yet still find this point of connection between them.

So Homer, and especially the Iliad, breaks all of those norms when it comes to traditional storytelling, and that's why I think it's a work that still baffles and intrigues so many classicists. That's why in my previous answer I said that it's important to keep an open mind, and to try to avoid blindly applying literary criticism devices such as cause-and-effect analyses or importing modern moral judgement and anachronistic theories in works like Homer.

I hope this helped! I love talking about the Iliad so if you have any more questions I'd gladly answer them <3

P.S. WOW that professor really needs to get their facts straight lmao, I'm sorry your first contact with the Iliad and Achilles was through a lens like that. It always astounds me how little some people actually know about the subjects they're supposed to be experts in, like to talk about Achilles, a character from the ILIAD, and to refer to him as a "rapist", a thing that only appears in later Roman works which were basically ILIAD FANFIC LMAO, and BAD fanfic at that because it was essentially anti-Greek propaganda......... wow wow wow

P.S.2 unless the "rapist" thing refers to him sleeping with Briseis/a slave, which WOW once again extremely myopic take, very culturally and contextually tone deaf, I wish they actually do their research and stop spreading slander, that's slander, like come ON

#the iliad#homer's iliad#greek mythology#achilles#johaerys rambles#johaerys is physically incapable of shutting up#seriously though what IS it with all those classics teachers hating on the iliad like what gives??#what did Achilles ever do to you??? ;w;#he's a noble warrior and a beautiful princess and has never done anything wrong ever in his entire life

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

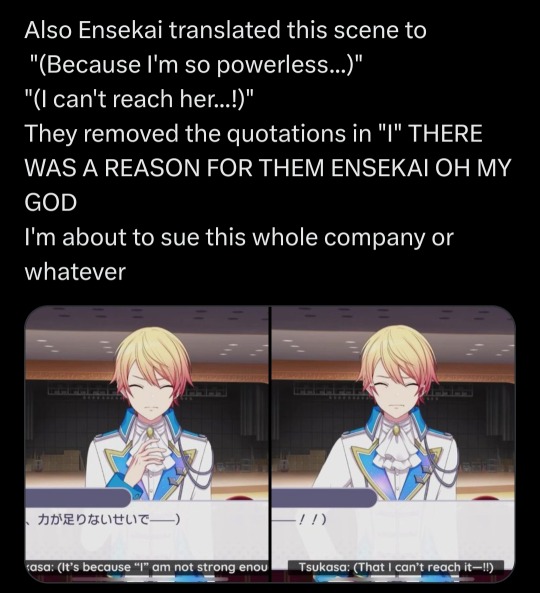

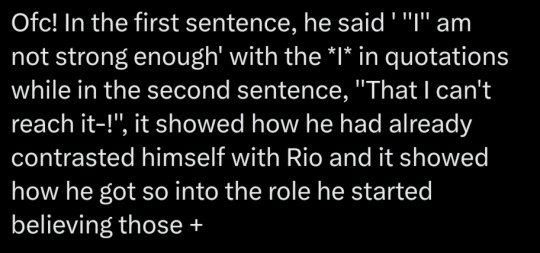

I decided to go on a Hiatus because I want to step back from prsk fandom buat I need to say something about this take (warning for Ensekai leaks)

Translation is fucking hard

What's impressive about this scene is Tsukasa specifically use BOKU (僕) and not his preferred pronoun ORE (オレ) to call himself

The emphasis is there so the JP readers could understand how impactful the fact that Tsukasa is not even using his preferred first pronoun because he's actually not being himself but being RIO EVEN IN HIS OWN HEAD

Tsukasa isn't being himself. On the contrary, he's completely, 100% become Rio at that moment

While English has a lot of third person pronouns, Japan has a lot of first person pronouns (compared to English measly "I"). Just like Western has their preferred pronouns, so does Japanese (of course their 1st person pronoun is interchangeable in the context of social interactions). Too bad that this nuance for Tsukasa's dialogue can't be replicated in English. I argue that putting emphasis on the "I" actually do Jack Shit because the emphasis is on the DIFFERENT PRONOUN IN JP. It's like when you hear someone calls a person as a "he" for a long time but then one person suddenly calls that person as "she" (I think, I know western are kinda sensitive on their pronouns but I can't really relate). Anyway it's THAT jarring

The second line is where the tl team kinda needs to wrack their brain, 届かない. No subject, no object. The scene before the sentence flashed back to Tsukasa crying after remembering how he felt how unreachable his own Phoenix is, and it's how he understands Rio's helplessness right at that moment. Using "it" actually makes the sentence sounds pretty vague. What does "it" refer to? "The level that he wants to reach?" It only applied to Tsukasa and not Rio. "The phoenix"? Kinda rude to call the phoenix as "it" though. Besides, using EN pronouns, Tsukasa's phoenix is a "he" while Rio's phoenix is a "she". That's why JP can have that sweet ambiguity while the EN translators need to think super hard about the implied object here.

There's two nuances happening here, and the Ensekai tl team decided to translate it by context of Tsukasa AS Rio: "I can't reach her". I'm guessing that they agreed that the flashback to that scene in chapter 7 means that Tsukasa at that moment completely understands Rio, HE'S RIO BECAUSE HE USES 僕, so they decided that it's Rio's thought and not Tsukasa even though the text box says Tsukasa and the JP implied that Rio and Tsukasa become one. I think the the EN line is okay, kinda missing some deep nuances but that's what translation is. You can't expect to be able to translate all those cultural nuances.

Maybe the alternatives might be "I can't reach my/the phoenix?" More straightforward but we can have a nice title drop lol

#I'm working on my master's degree on translation rn so I know I have some rights to critique some official translation choices#The one about 大好き into cares about is kinda 50:50 but I guess they use modulation cause in JP 大好き CAN be used platonically#The Ensekai team knows that both JP and en prsk fandom is infamous for discourses so they tried to make it as platonic as possible#The JP fandom is (arguably) calmer than the en one but it's still bad in terms of animangamobage JP fandom#It's 1 am and I'm sleepy#prsk#project sekai#hatsune miku colorful stage#When i heard Tsukasa's 僕 in his inner dialogue I screamed because HOLY SHIT HE REALLY DID BECOME RIO#So I guess the Ensekai tl team also went along with yeah that's Rio#He's weak so he can't reach his phoenix which is a she

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

SPOILERS FOR OPPENHEIMER BY THE WAY BECAUSE I HAVE WAY TOO MANY THOUGHTS ABOUT THIS MOVIE AND WANT TO DISSECT IT

Okay so I know there are some very reasonable and valuable complaints, comments, and criticisms about Oppenheimer and how it handles the ACTUAL victims of the war, martyrizing Oppenheimer, an arguably very gray character in reality for more reasons than the atomic bomb and...trying to poison his mentor. You know. The basics.

THAT SAID I AM GOING ABSOLUTELY FERAL FOR CILLIAN MURPHY'S PORTRAYAL OF OPPENHEIMER LIKE I HAVE A 3 IN 1 DEAL FOR HYPERFIXATIONS RIGHT NOW I THINK BECAUSE WE HAVE THE ACTUAL MOVIE, CILLIAN, AND THEN OPPENHEIMER. AGH. LOSING MY MIND. PICKING APART EVERY SCENE AND DETAIL WHILE ALSO GUSHING ABOUT CILLIAN'S PERFORMANCE.

on that note here's some things I worked out about the movie, or rather, my takes on them for those curious (some of these are definitely a stretch, but I like seeing how far I can push a metaphor once I find one, so here we go):

Lotta controversy about the "I am become death" quote during the sex scene, which, fair. I can see why they included it though, upon reflection. In the moment, it just feels like a strange foreshadowing of the bomb itself, which did Not resonate with me and seemed fairly jarring, but upon closer inspection, I think the relevance of that quote in *that* context is that this is the first person Oppenheimer lost. Jean needed Oppenheimer, and he blamed himself for her suicide (or murder, maybe). This was the first time he "became death, destroyer of worlds"; the first marble in the bowl, which mirrors Oppie's reaction to the bomb's actual detonation quite well, too, I think. Something terrible has just happened, and yet the expectation is that Oppenheimer shows up and pretends all is well and he isn't horribly damaged, just martyring on.

SECOND

The orange from Rabi might be a bit deep or I might be a bit stupid. Oranges tend to symbolize positivity and aid, so being told to eat one by a friend in his most vulnerable moment is a kindness, hence some symbolism there. I did unpack this deeper though, say, such that oranges need to be peeled to get to the sweetness, and they are one of the sweetest citrus fruits, though they maintain their tang. This represents perfectly how the orange delivery felt in that scene; sweetness from Rabi in a moment of vulnerability, the orange peel gone, the bitter and trauma numbed exterior of Oppenheimer stripped away for just a moment before the sour slammed back in full force. Also just. Really stretching it but oranges being segmented could both represent a fractured mind AND the different perspectives on Oppenheimer as a whole and his reputation to this day.

Oh and General Groves when telling Oppenheimer he's essentially done with him but will ..try? To keep in contact? And update him?? He's buttoning up his coat if I remember right, mirroring his guard getting put up as he ends his amicable dealings and negotiations with Oppenheimer, adding layers and making himself less vulnerable. Oppie, meanwhile, smokes as the quiet, socially acceptable way to perform an anxious ritual.

Also the RAIN. Don't have this one fully unpacked yet and maybe never will but Cillian in an interview mentioned that Nolan described Oppenheimer as "dancing between the raindrops" and this has only half clicked with me but oh well here we go. The basic idea is likely that Oppenheimer doesn't abide by just one grouping of people or their ideas, or hop on any flow bound for one particular destination. Rather, he dances in the space between; in the uncertainty that looms closer towards the ground the further things fall. I think this works decently with what I've listened to and read about Oppenheimer as a person, saying he'd follow recent physics, always growing impatient with the current field he was in and seeking something more...I don't like the use of this word in relation to science but "trendy." I guess the dust particles and whatnot in the headspace sequences work in line with the whole rain theory too in terms of how Oppenheimer doesn't just think about the interactions and the space between, but lives and breathes it as the space between the raindrops; between those that make the biggest splashes, as he gets caught in the ripples. Also given his anti-war rhetoric throughout the movie I feel like there's maybe a fire/water thing going on with him trying to quench the bomb he created but ultimately failing? Who knows. Maybe it's just rain.

Anyways here's all the ramblings I did to myself to reach these conclusions. They are incomprehensible.

#oppenheimer#cillian murphy#christopher nolan#oppenheimer spoilers#barbenheimer#god dammit cillian has me in a chokehold#american prometheus#j robert oppenheimer#my ap lit brain was Not Okay after that movie

144 notes

·

View notes

Text

So, i was trying to think of the strange connection that there is between Danny Phantom fans and Steven Universe fans, aside from SU being a show that was very popular on its moment. Like one show is from 20 years ago and the other is from last decade, both with different executions and genres.

...Which lead me to write a whole essay no one asked for, so here you go:

One of the first things that comes to mind is how the main leads are hybrids- Danny Fenton is half human/half ghost, Steven is half human/ half gem. And like both series give an idea that they are pretty unique in their experience as hybrids and they both belong to both worlds yet not fully to either of them.

Danny has a lot of issues with having to hide his part of himself from the world, his parents included. Meanwhile, Steven doesn't understand certain social norms and can feel disconnected from other teens around his age, having lived a somewhat recluded childhood from his peers. (This gets more explored in Future)

Aside from the struggles that being an hybrid it brings to them, they have episodes about learning new powers or learning how to control them. You see them start rather powerless only to become pretty OP on the long run. -Steven getting tired for summoning one shield to being able to do it without sweat-Danny having his powers glitching at the start to gain a power like Ghost Wail later on, etc.

Another thing that Danny and Steven share in common is that they want to help and be useful. In Steven's case, he wants to help people with their problems or "fix" them. Over time Steven starts to define his identity around helping others a little too much to the point that he doesn't know who to be outside of that.

A pretty common headcanon for Danny in the DP fandom is that his ghost obsession is about having to protect everyone he can, something you can see in the series in a way. After Phantom Planet, Danny doesn't know who to be outside being the hero and feels that people don't need him anymore in the context the world having being saved after the series finale. ( A Glitch in Time)

Both try solving problems talking it out if possible, if it is a misunderstanding or they think the antagonist can be reasoned with.

With Steven, he doesn't need an explanation as most people know his personality, for Danny- it depends on the situation and his mood, sometimes being kinder and other times more violent. I would argue again that he still tries to talk things out when he sees that violence isn't necessary -just not the same as Steven

That's not to say their characters are the same, in fact their personalities are pretty different and their ways to approaching problems differs too. They do, however, share some parallels in their character arcs that i already discussed.

Another aspect are the main antagonists, both Steven Universe and Danny Phantom have their antagonists have motivations outside of being evil for the sake of being evil.

In Steven Universe this is a main theme and i don't think it doesn't need much introduction. Antagonists (most Homeworld gems) have been taught and were socialized to act in a specific way in the totalitarian society they were born into. Examples of this are: Peridot, Jasper and Lapis- these motivations can be mixed with revenge or similar things as well.

In Danny Phantom the main antagonists are Vlad Masters/Plasmius and Valerie Gray, both characters who aren't evil by nature and the series leaves clear that their antagonism comes from what happened to them and the decisions they took in result of that.

Vlad Masters role as a villain comes from the insolation and abandonment issues that came from the Ghost portal accident in college caused by Danny's father, Jack Fenton. Vlad became obsessed with getting revenge on Jack and believing he "stole" a family that should have been his.

Valerie comes from her blaming Phantom for (accidentally) ruining her life and trying to get revenge on him, becoming a ghost hunter. Valerie's role is a mix between anti-hero and antagonist since she wants to protect people but opposes Phantom at the same time. Eventually she becomes a bit of a friendenemy to Phantom over the course of the seasons.

Other recurrent antagonists have their own motives to do bad things ( Sidney, Desiree, Ember) while others are more naturally classic evil (Ghost King, Spectra). It depends on the character one is talking about.

Diving more into Vlad Plasmius, both series have this idea of "legacy", as like protagonist having to deal with what their parent/s "left behind for them".

For Steven is a huge deal for him since many of the antagonists who attack him are for things his mother Rose Quartz did, having Steven deal with all this issues and believing he has to fix them, blaming himself for what how Rose hurt people in different ways.

As for Danny, Vlad Masters' antagonism comes from the portal accident caused by Jack, Danny's father, when Vlad, Jack and Maddie (Danny's mom) were still friends in college. In a way Danny has to deal with something that was caused by his father. It isn't something he choose to but yet still brings him a lot of problems to his life.

I'm not sure which character from SU Vlad could be compared to, but i would say that Spinel is the closest one, since Spinel was abandoned by Rose Quartz (as Pink Diamond), who was her best friend, similar to what supposely happened between Vlad and Jack after the ghost portal accident.

Other theme is the idea of redemption, or how you can be your worst own enemy. As i mentioned, antagonists in SU usually get redemmed and change their ways from the systematic ideas they were raised in. There is this idea that people have the capacity to change if they propose themselves to.

In Steven Universe Future, Steven is "his worst enemy" as he has to deal with his own demons he has been avoiding for years for trying to repress them or being too busy helping other people. He goes through a negative corruption arc because of this, ending with him realizing that he can't hiding his issues and needs help with them.

In the Danny Phantom series, this is very important theme in "The Ultimate Enemy", where Danny is confronted by the possible evil future version of himself, called Dan Phantom in the DP fandom. Danny battles against this version of himself and tries to fix his mistake, proving that he can avoid that future from happening.

Danny also meets Vlad Masters in the dark future timeline in this special, who regrets his actions after so many years passed and how he accidentally helped with creating Dan in that timeline.

A Glitch in Time expands on this theme further by exploring Vlad and Dan's motivations a lot more and giving them second chances. The novel itself shares parallels with Steven Universe and SU Future in multiple ways.

Back to Dan Phantom, he shares quite a lot of things in common with Malachite to the point people have pointed out these parallels.