#when arguably THE central theme of the work amounts to 'make love not war'

Text

people will debate endlessly "is SNK fascist" "is it pacifist" "is it liberal/centrist" "is it anti-racist" "is it nationalist" which like are valid questions when it comes to discussing the social and political implications of a work and its themes but if you were to ask me i would say that Isayama's intended main thesis is "you should enjoy when it's a nice day out" and the geopolitical stuff is more or less window-dressing.

#kind of joking here. partly not joking tho#and of course using such political themes as window-dressing for a fundamentally less-than-political story is questionable#from an artistic or a social standpoint#but i am just amused sometimes by the endless discourse over whether Isayama is 'imperialist' or 'anti-imperialist'#when arguably THE central theme of the work amounts to 'make love not war'#(if this post sounds like an endorsement or a condemnation of SNK or its author please be assured that it is intended as neither.)

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why is one of the first things that we ever learn about Roy Mustang the fact that he is useless in the rain?

So at this point, I think we’ve all heard or realized that Roy Mustang’s rain/water motif is not just a physical limitation for his alchemy but also a symbol for his regret and “uselessness.” It’s a brilliant metaphor that elementally balances him out.

And it’s introduced the moment we meet him.

While it does serve as a bit of comic relief during the extremely intense first episode, the significance of it being in that episode is still important to Roy’s development and how the audience develops their understanding of him throughout the series.

First, we need to contextualize it. The first episode is centered around Isaac McDougal, the freezing alchemist (as in an alchemist who freezes, not a really really cold alchemist, although “Isaac the Really Really Cold Alchemist” would be a fantastic name. Anyways). Isaac’s goal is to freeze over Central Command via a city-wide transmutation circle using a philosopher’s stone.

The plot of the first episode is a parallel to the plot of the entire series, and it is full of foreshadowing. In terms of exposition, it isn’t very subtle. The basic exposition of characters like Ed, Al, and Roy is pretty much told to us through dialogue. However, that choice is justified. For people who are completely new to the FMA world, as I was when I watched this two years ago, the first episode has a lot going on. New members are not only meeting all the characters, but they are also trying to put together what alchemy is, where and when this is taking place, and who they should be rooting for. And THAT is where the brilliance (in my opinion) comes in. Watching the first episode through for the first time, the audience is rooting for Ed and Al (because they are the protagonists), and the military (because our protagonists trust them and are part of it). When our protagonists are told to capture Isaac and to view him as a traitor, we do, too. It’s only when Isaac confronts Ed about his beliefs about the military that we start to question our own. But even then, we aren’t given enough information to understand why we should question the military. However, watching the episode in hindsight, our loyalties are switched. Isaac becomes the hero trying to take down the evil military, and Ed, Al, and Mustang become the villains.

So, back to Roy. During the first episode, aside from getting the basics of who he is and what he does, we don’t learn much more about him. Just these two things:

1. He is a veteran of something called the Ishvalan War (and the Ishvalan War is apparently controversial based on conversations between Isaac and Roy and Isaac and Kimblee).

2. He can’t make things go sparky sparky when he gets wet.

And those two things are arguably the most important parts of who Mustang is and what he has been through.

First, let’s talk about Roy, Isaac, and Ishval. As the first episode unfolds, the audience knows nothing about what happened in Ishval. But Roy and Isaac do. In hindsight, knowing how Roy feels about the Ishvalan War and what he did there, why on Earth would he be calling Isaac a traitor? Roy knows that the military is corrupt (although not to the extent that he will). Roy’s biggest regret is blindly following orders in Ishval. Roy has his eyes set on becoming the Fuhrer and changing things. Roy is literally a genocidal war criminal who stages a coup from an ice cream truck and overthrows the military. And somehow Isaac is the traitor?

Roy is following orders because he has to in order to achieve his goal. He is putting on a loyal-to-the-military act and biding his time until he can admit to the world that Isaac was right.

Er, that his ideals were.

See, Isaac is Roy’s elemental opposite. Isaac is water, Roy is fire. He is also Roy’s narrative foil. While Isaac’s plan lacked patience and was too rash to ever succeed, Roy’s plan has taken him and will take him years, and he has been extremely careful curating it. It’s ironic to me that the character associated with water would act more rashly and have less patience than the character associated with fire. That’s not to say that Roy doesn’t act rashly. Roy’s impulsiveness and vengeance-driven actions are some of his greatest setbacks as a character.

But Roy is also intelligent and strategic in achieving his greater goals. His dependence is on his closest allies, while Isaac’s dependence is on a philosopher’s stone. And while the characters do not yet know the ingredients for stones in the first episode, Isaac’s use of one to accomplish his ultimate goal is what sets him apart from Roy and the Elrics. And yes, Roy does use a stone to regain his eyesight, but he does not depend on one during his coup. I would even argue that Isaac’s use of a philosopher’s stone could also be foreshadowing Roy’s eventual use of one in addition to foreshadowing the overall plot. It’s also important for us to see Isaac defeated in the first episode because it shows us that although philosopher’s stones remove the law of equivalent exchange, they do not make the user all-powerful. At the end of the day, the user can still be defeated.

Another difference between the two is how their limitations are presented in this episode. Isaac’s alchemy is unlimited because of the philosopher’s stone, but the first thing we learn about Roy Mustang’s alchemy is that he is limited by water. This leads me to the second point.

Establishing Roy’s limitations in the first episode does a few things for us:

First, it establishes that he is dependent on Riza and trusts her in his most vulnerable moments. That even though Riza knows how easily Roy can be overpowered, she still chooses to stay by his side, protect him, and help him accomplish whatever he sets out to do.

Second, we get a peek at Mustang’s creativity and perseverance. His determination and intelligence is displayed in how he overcomes the limitations presented, and it makes us want to root for him.

Third, it gives us some information as to how alchemy works. We see a few types of alchemy in this episode: Ed’s without a circle, Isaacs’s with a circle and elemental, Roy’s with his transmutation circle gloves and unique flame alchemy, and Major Armstrong’s forceful style. This helps us get an idea of the varying styles of alchemy, varying ways of how it can be used and manipulated, and the different forces that use it for their benefit or the benefit of others.

Lastly, it begins the “uselessness” theme. It tells us that even though Mustang is an extremely powerful alchemist, there are still things that he can’t control. That there are forces that can overpower him, and the best thing he can do is to get back up and try again until he accomplishes his goal. We also see Roy’s anger at those forces, the ones that render him unable to do anything. And we see him use that anger to fuel his alchemy and overpower them.

“The power of one man does not amount to much, but however little strength I am capable of... I’ll do everything humanly possible to protect the people I love, and in turn they’ll protect the ones they love. It seems like the least we tiny humans can do for each other.”

Roy Mustang, Fullmetal Alchemist: Brotherhood

#fmab#roy mustang#royai#riza hawkeye#fullmetal alchemist#fullmetal alchemist brotherhood#fullmetal alchimist brotherhood#fma#fullmetal alchemist: brotherhood#elrics-inferno

923 notes

·

View notes

Text

If Jason wanted to convince me that Lxa was the love of Clarke's life, he wouldn't have killed her off, effectively cutting their love story permanently, with 4.5 seasons left of the show. Their arc, starting with their introduction in 2x07 and concluding with L's death in 3x07, is 17 episodes long, accounting for 17% of the entire narrative. If I generously add 3x16 to the count, an episode in which L is already dead in the corporeal world Clarke is trying to return to, it's a whopping, grand total of 18%. An 18% congruous with Clarke's intense connection to Bellamy and vice versa, which even A.lycia confirmed as romantic. Feelings romantic enough to spur the formation of a love triangle. An 18% ignoring Clarke's ultimate choice to go back to her people when L wanted her to stay.

CL is a chapter in the story begun and wrapped up in the first half of the narrative. And that's omitting further illumination on the finer details making CL so problematic for Clarke. Do you expect me to believe it was coincidental for CL to occur at a time when Clarke was spiraling down a dark path, commencing with Finn's death? Who played a hand in forcing Clarke's own hand, with Finn, and TonDC, and Mount Weather? Whose example inspired her to ensnare herself in armor and warpaint to be strong enough to save her people? Whose behavior did she emulate in the pushing away of support from her people? Who gave her a place to continue hiding from Bellamy, her mom, and her friends? A place to be someone other than Clarke Griffin? In lieu of facing her fears like the heroine she is? The purpose of CL wasn't to provide Clarke with a magnificent, fairy tale romance gone tragically wrong. I believe Jason's intent with the relationship aimed to further damage Clarke's psyche after L's death, to solidify the belief that her love is not only deadly to its recipients but renders her too weak to do what must be done for survival.

After 3x16, CL is an often superfluous namedrop or two per season for Clarke to briefly react to before carrying on with the plot. Season 5 aside, most of these references are needless enough to be able to interpret them as attempts at reparations for the L/CL fandom's benefit -and their views- without altering the course of the story. Crazy me for thinking it's not enough to constitute an ongoing love story. Crazy me for not thinking this was on par with interactions between living characters. Crazy me for thinking it doesn't befit a love story for the protagonist.

This sliver of the story is what Jason and the CLs would have us unquestionably believe is the pervasive love story of The 100's seven seasons?

Despite his lie and the constant gaslighting from the pineapple CLs, some of us know how to decipher what a temporary love interest is. Lxa? I think you know where I'm heading with this.

I'll acknowledge my admittedly negative appraisal of CL as someone who recognizes its value to the LGBT+ community and treats it as valid while not caring for L/CL on a narrative level. I felt, when swayed by L's influence, Clarke became the antithesis of what I found admirable about her. I resented Clarke's acquiescence of her power to the commander. I wanted nothing more than to remove the wedge L had driven between Clarke and Bellamy.

Let me try to give L/CL the benefit of the doubt for a minute. I don't hold L as responsible for Clarke's choices, but I recognize the prominent role she played in their upbringing. The push and pull was an intriguing aspect of their dynamic, as was the chance to meet a manifestation of who Clarke might have been if she was all head, no heart. Her fall from grace was arguably necessary for her to be a fully-rounded character, not a Mary Sue. It wouldn't be realistic for the protagonist of a tragic story about a brutal world to be a pure cinnamon roll. When forgiveness is an innate theme with Clarke, it would be my bias at work if I was content with her applying it to everyone but Lxa. Clarke saw enough commonalities between her and L to identify with the latter. When she extended forgiveness to L, I believe it was her way of taking the first step on the path to making peace with herself by proxy. None of this means I wanted them paired up. At best, I made my peace with seeing the relationship through to its eventual end. In time for L's death, ironically. My passivity about them notwithstanding, my conclusions are, however, supported by canon.

If I may submit a Doylist reason for romantic CL? Jason knew he had a massive subfandom itching to see them coupled, thereby boosting ratings and generating media buzz. A Watsonian reason? Without relevance, I think L would have been another Anya to Clarke. Grapple shortly with the unfair taking of a life right as they choose to steer towards unity, melancholy giving way to the inconvenience of the loss of a potential, powerful political ally. Romance ensured her arc with L would have the designated impact on Clarke's character moving forward in the next act.

For a show not about relationships, Jason has routinely used romantic love as a shorthand for character and dynamic development. It's happened with so many hastily strung together pairings. And when it does, everyone and their mother bends over backward to defend the relationship. It's romantic because it just is. Didn't you see the kissing? Romantic.

No, The 100 at its core is not about relationships, romantic and otherwise. But stack the number of fans invested exclusively by the action against those of us appreciating a strong plot but are emotionally attached to the characters and dynamics. Who do we think wins? Jason can cry all he wants over an audience refusing to be dazzled solely by his flashy sci-fi.

Funnily enough, "not about relationships'' is only ever applied to Bellarke. Bellarke, a relationship so consistently significant, it's the central dynamic of the show. The backbone on which the story is predicated. Only with Bellarke does it become super imperative to represent male-female platonic relationships. As if Bellarke is the end all, be all of platonic friendship representation on this show. In every single television show in the history of television shows.

Where was this advocacy when B/echo was foisted upon on us after one scene between them where he didn't outright hate Echo? When one interaction before that, he nearly choked the life out of her. If male-female friendship on TV is so sparse, why didn't B/ravens celebrate the familial relationship between Bellamy and Raven? Isn't the fact that they interpret Clarke as abusive to Bellamy all the more reason to praise his oh-so-healthy friendship with Raven as friendship? They might be the one group of shippers at the least liberty to use this argument against Bellarke, lest they want to hear the cacophony of our fandom's laughter at the sheer hypocrisy of the joke. Instead, they've held on with an iron grip to the one sex scene from practically three lifetimes ago when the characters were distracting themselves from their feelings on OTHER people? They've recalled this as "proof" of romance while silent on (or misconstruing) the 99% of narrative wherein they were platonic and the 100% of the time they were canonically non-romantic.

Bellarke is only non-romantic if you believe love stories are told in the space of time it takes for Characters A & B to make out and screw each other onscreen, a timespan amounting to less than the intermission of a quick bathroom break. If it sounds ridiculous, it's because it is. And yet, some can't wrap their heads around the idea that maybe, just maybe, a well-written love story in its entirety is denoted by more than two insubstantial markers and unreliable qualifiers. B/raven had sex, and the deed didn't fashion them into a romance. Jasper and Maya kissed but didn't have sex. Were they half a romantic relationship? Bellarke is paralleled to romantic couples all the time, but it counts for nothing in the eyes of their rival-ship fandom adversaries. Take ship wars out of it by considering Mackson. Like B/echo, the show informed us that Mackson became a couple post-Praimfaya, offscreen, via a kiss. Does anyone fancy them an epic love story with their whisper of a buildup? Since a kiss is all it takes, as dictated by fandom parameters, we should.

If Characters A & B are ensconced in a romantic storyline, then by definition, their relationship is neither non-romantic nor fanon. "Platonic" rings hollow as a descriptor for feelings canonically not so.

If the rest of the fandom doesn't want to take our word for granted, Bob confirmed Bellarke as romantic. Is he as delusional as we are? Bob is not a shipper, but he knows what he was told to perform and how. Why do the pineapples twist themselves in knots to discredit his word? If they are so assured by Jason's word-of-god affirmation, then what credibility does it bear to have Bellarke validated by someone other than the one in charge? They're so quick to aggressively repudiate any statement less than "CL is everything. Nothing else exists. CL is the only fictional love story in The 100, nay, the WORLD. CL is the single greatest man-made invention since the advent of the wheel."

We've all seen a show with a romantic relationship between the leads at the core of the story. We all know the definition of slowburn. We can pinpoint the tropes used to convey romantic feelings. We know conflict is how stories are told. We know when interferences are meant to separate them. We know when obstacles are overcome, they're stronger for it. We know that's why the hurdles exist. We know those impediments often take the shape of interim, third-party love interests. We know what love triangles are. We know pining and longing.

Jason wasn't revolutionary in his structure of Bellarke. He wasn't sly. Jason modeled them no differently than most other shows do with their main romances. Subtler and slower, sure. Sometimes not subtle at all. There's no subtlety in having Clarke viscerally react to multiple shots of Bellamy with his girlfriend. No subtlety in him prioritizing her life over the others in Sanctum's clutches. In her prioritizing his life above all the other lives she was sure would perish if he opened the bunker door. There is no subtlety in Bellamy poisoning his sister to stave off Clarke's impending execution. In her relinquishing 50 Arkadian lives for him after it killed her to choose only 100 to preserve. In her sending the daughter Clarke was hellbent to protect, into the trenches to save him. In him marching across enemy lines to rescue her. In her surrender to her kidnapper to march to potential death, to prevent Bellamy's immediate one. No subtlety in Josie's callouts. No subtlety in Lxa's successful use of his name to convince Clarke to let a bomb drop on an unsuspecting village. Bet every dollar you have that the list goes on and on.

There are a lot of layers to what this show was. It was a tragedy, with hope for light at the end of the tunnel. It was, first and foremost, a post-apocalyptic sci-fi survival drama. Within this overarch is the story of how the union of Clarke Griffin and Bellamy Blake saves humanity, ushering in an age of peace. In this regard, their relationship transcended romance. But with the two of them growing exponentially more intimate each season, pulled apart by obstacles only to draw closer once again, theirs was a love story. A romantic opus, the crescendo timed in such a way that the resolution of this storyline -the moment they get together- would align with the resolution of the main plot. Tying Bellarke to the completion of this tale made them more meaningful than any other relationship on this show, not less.

Whereas the trend with every other pair was to chronicle whether they survived this hostile world intact or succumbed to it, Bellarke was a slowburn. A unique appellation for the couples on this show, but not disqualifying them from romantic acknowledgment.

Framing Bellarke in this manner was 100% Jason's choice. If he wanted the audience to treat them as platonic, he should have made it clear within the narrative itself, not through vague, word-of-god dispatches. A mishandled 180-degree swerve at the clutch as a consequence of extra-textual factors doesn't negate the 84% of the story prior. It's just bad writing to not follow through. And Jason's poor, nearsighted decisions ruined a hell of a lot more than a Bellarke endgame.

The problem is, when Bellarke is legitimized, the pineapples are yanked out of their fantasies where they get to pretend the quoted exaggerations above are real. Here I'm embellishing, but some of them have deeply ingrained their identities in CL to the degree where hyperbole is rechristened to incontestable facts. An endorsement for Bellarke is an obtrusive reminder of the not all-encompassing reception of their ship. A lack of positive sentiment is an attack on their OTP, elevated to an attack on their identity. Before long, it ascends to an alleged offense to their right to exist. The perpetrators of this evil against humanity are the enemy, and they must attack in kind, in defense of themselves.

Truthfully, I think it's sad, the connotation of human happiness wholly dependent on the outcome of a fictional liaison already terminated years ago. I'm not unaware of the marginalization of minorities, of the LGBT+ community, in media. I haven't buried my head in the sand to pretend there aren't horrible crimes committed against them. I don't pretend prejudice isn't rampant. When defense and education devolve into hatred and libel for asinine reasons, though, the line has been crossed. You don't get a free pass to hurt someone with your words over a damn ship war. No matter how hard you try to dress it up as righteous social justice, I assure you, you're woefully transparent.

#my thoughts#thoughts i wanted off my chest#don't mind me#i'm trying to keep this out of the main tags#la dee da#ok here we go#bellarke#anti jroth#the 100#cl#the 100 ships#long post#fandom wank#sorta#if you read all this#you're a real trooper#i salute you#anticlexa#antibecho#antibraven#late night rambling#an autobiography#my post

252 notes

·

View notes

Text

More about my morally-grey heroines and their messed-up relationships

I wanted to elaborate on this post I wrote about D&F and BFS, but it turns out that adding readmore links to reblogs is a PITA, and I just now that this is gonna turn into a fucking novelette.

So here we go.

Time to go into some detail about this!

Let’s define our terms:

“Decline and Fall” is my 120K+ series of loosely chronological, interconnected short fics, set in a tiny fandom for a visual novel that’s been in alpha development since 2015. For the record, the word count disincludes unfinished drafts, and stories that I’m holding back because they’re based on canon spoilers.

“Blood from Stone“ is my 100K unfinished Skyrim WIP, which began as a response to a kink meme prompt, and is not so much a rarepair as a non-existent one.

Both of these stories centrally feature young female protagonists and their sexual relationship with a much older man. Both heroines are... “grey” to say the least.

Let’s compare our fandoms, shall we?

Skyrim is a juggernaut fandom for a super-popular RPG which is part of a 30-yo franchise. The setting is moderately dark and casually sprinkled with murder cults, cannibalism, secret police death squads, and the prison industrial complex. The player character can be a thief and a murderer and everyone just learns to be okay with it because the only alternative is a fiery apocalypse. They also rob graves for the lulz.

Seven Kingdoms: The Princess Problem is a pinkie-toe-sized fandom for a hybrid RPG and dating sim where attractive young people flirt and date for the purpose of brokering world peace. The setting is one where you can actually broker world peace effectively. The player character can perpetrate a fair amount of proxy violence, but maintaining a good reputation dishonestly is legitimately difficult.

Now, let’s compare our heroines:

Corinne is a 24-year-old bounty hunter who became a folk hero, a soldier, and a cult assassin. She’s living alone and working for a living since she was 18. She’s never been in love, but she’s had multiple sexual and romantic relationships in the past. I deliberately wrote her as being very sexually confident and self-assured. She also has combat training, magical training, her special Dragonborn powers, and an incalculable amount of social clout. By every metric, she’s a powerful character. Though she can talk her way out of a tight spot (all my favorite characters can), she can also fight her way out.

Verity is (at the beginning of D&F) not yet 18 years old. She’s a princess from a very conservative kingdom who was raised to become a barter bride in a diplomatic marriage. The values that were passed to her were duty, tradition, and absolute obedience. Her primary skills are social, charisma, eloquence, and persuasion. Then she was dropped into the deep water of a diplomatic summit and had the weight of future history put on her shoulders, without ever having been taught how to make her own decisions or live with her regret.

To sum up, we have one hyper-competent, confident, and independent badass, universally recognized as powerful and dangerous, and then we have someone who’s basically a deconstruction of a traditional fantasy princess.

Okay, what about the more specific setting within the game world?

BFS is set in Markarth, arguably the most corrupt city in Skyrim, and the site of a localized war, on top of the 2-3 other wars that Skyrim has going on. The city is controlled by the cartel-like Silver-Blood family, and their enemies are swiftly and brutally eliminated. The rule of law is a joke. When the player character arrives at Markarth, they witness a chain or murders and are drawn into a conspiracy that sees them sentenced to life in prison for a crime they didn’t commit. The ruling elite suppress the native underclass by a variety of inventive methods. The roads into the city are controlled by the remnants of a violent but failed uprising, and this uprising is actually the origin story of Skyrim’s entire civil war storyline.

D&F is set in Revaire, explicitly the most violently war-torn of the seven kingdoms. Once the epicenter of a conquering empire, it was a country full of arts and culture, until a bloody coup slaughtered the entire royal line and instituted a new and more brutal regime. The new regime is on shaky grounds and foresighted people predict its imminent fall to rebel forces. So much, so canon. In D&F, I made a point of developing the new royals and their small coterie of supporters, as well as illustrating their constant struggle to conceal how widely reviled they are by the populace, and most of the former nobility. Their apathy to the plight of the common people is underscored in contrast to Verity’s compassion, which is ridiculed as a sentimental feminine affectation.

I’m attracted to certain themes, as you might have noticed.

Now, we get to talk about love interests.

Thongvor Silver-Blood is rather anemically characterized in Skyrim’s canon, so much of the information that I include in BFS is inferred. From his limited number of dialogues in the game, we know that he’s politically ambitious, a Stormcloak supporter, easily angered, and that he has one legitimate friend in the city. Like most Skyrim characters of his age bracket, he served in the Great War. He’s defined by his relationship to his generational cohort. In BFS, he’s def8ined in contrast to his brother. Thonar is comfortable being thought of as a villain. Thongvor still needs to believe that he’s the good guy. And I’m gonna get more into that in later chapters, too.

As a love interest, he’s initially in awe of Corinne, and always genuinely adoring, but more than a little jealous and possessive. BFS is not a story about love redeeming bad men (don’t get me started), but Thongvor shows different sides of his personality to different people, and the side that Corinne gets to see is much nicer than what most people do.

Hyperion Asper is a character of my own devising, whose existence in 7KPP canon is purely implied. We know his children, Jarrod and Gisette, and we knew that he organized a coup to seize the throne. I posit him as a tyrant and unrepentant child-killer (not directly stated in D&F, at least not yet). He’s ruthless and manipulative and his sole purpose is maintaining a sense of personal power. I structured him as the bad example that Jarrod tries -- and fails -- to live up to.

As a love interest... look, he’s a man who’s cheating on his wife with his son’s wife. He seduces Verity and manipulates her, and takes a special delight in pushing her buttons. All his compliments to her are mean-spirited and back-handed. He’s also jealous and possessive... which is especially pathetic, since he’s jealous of his own son, whom Verity doesn’t even like. His rage is a constant implied undercurrent in the narrative.

And the relationship dynamics themselves?

Corinne kisses Thongvor, proposes marriage to him, and then sleeps with him before riding off into mortal danger. She’s fond and affectionate, but she shies away from intense emotions, whether negative or positive. Since they spend most of their time apart, their marriage has been defined by Thongvor yearning like a sailor’s wife, while Corinne ran around doing violence and crime. They only just had their first fight. It will change when they get to spend some more significant time together... but on the whole, their marriage is fairly happy, and the emotional dynamic favors Corinne -- so far. It’s not a pure gender reversal, but that element is definitely dominant.

Hyperion starts seducing Verity on their very first meeting, and relies on a combination of magnetic attraction and Verity’s inexperience in life to keep her coming back, against her better judgment. Their relationship is mutually defined by a combination of attraction and resentment of that attraction. The danger of the situation is an essential element, to the point where it’s hard to imagine their affair would survive without it. It’s a puzzle and a battle, a source of fascination but not of comfort. There’s lust involved, and curiosity, but not a shred of love or even like. The closest thing to genuine affection is when Verity briefly imagines that there could be a version of Hyperion she actually liked, cobbled from his various, hidden good qualities. Any trappings of a genuine relationship are deliberately discordant.

I have tried, more than once, to imagine an alternate universe in which these two could be happy. It can’t be done. they are a study in dysfunction.

So where’s the similarity, with all these differences outlined?

Corinne’s choice to marry into the Silver-Blood family makes her complicit in their rule of the Reach, corrupt and reactionary as it is. Her reluctance to accept being called by their name reflects a reluctance to confront unpleasant truths that’s fundamental to her character. Choosing to be one of them affects and will continue to affect how other people see her, mostly negatively, and mostly without her being aware of it. Being Thongvor’s wife has gained her enemies. The fact that she doesn’t share his more reactionary views is something that they’ve both chosen to elegantly ignore, but the rest of the world won’t be so generous.

Verity’s choice to marry into the Revaire royal family makes her complicit in their violence against the forces rebelling against them, albeit in a more subtle way. Her personal dislike of Jarrod and the fact that their marriage was purely political will not absolve her in anyone’s eyes. Neither will her compassionate and charitable character, which can only be seen as a fig leaf to the Revaire royals’ general brutality. She has lost at least one good friend -- who will never see her the same way, since she chose to throw her lot in with his enemies. She will go down in history as an Asper wife -- but if she’s lucky, not just as that.

Both Corinne and Verity choose to accept some of the violence of the system that they live under, in order to serve their own lofty, long-term goals. Both of them are more image-driven than they care to admit, and though they are genuinely caring and compassionate, they will readily sacrifice compassion in service on their goals. They are queens (or queen-like figures), one-degree-of-separation members of the ruling class, implicated but not directly in control.

And their relationships serve to highlight what they are willing to accept, even though it goes against their conscience.

Is there a conclusion to be drawn here?

Sort of. I want to write about power, compromise and complicity. For whatever reason, it turns out that yw/om relationships are... a really good vehicle for exploring that. I can’t really explain why that is, just yet. I just... have had these thoughts floating, unstructured, in my head for months on end. I needed to get them out on paper, and give them some semblance of order.

I don’t even know why anyone but me would read this, as long and meandering as it is. But having it accessible might be of use to me.

#blood from stone#decline and fall#train wreck verity#i don't know why anyone would read this#it's nearly 2k words#and it has no real conclusion#hazel's d&f/bfs meta spiel

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Watchmen - Movie blog

(SPOILER WARNING: The following is an in-depth critical analysis. if you haven’t seen this movie yet, you may want to before reading this review)

A movie adaptation of Watchmen had been in development in some form or another since the graphic novel was first published back in 1987. Over the course of its two decade development cycle, being passed from filmmaker to filmmaker who each had their own vision of what a Watchmen movie should be, fans objected to the idea of a movie adaptation, describing Watchmen as ‘unfilmmable.’ Alan Moore himself condemned the effort to adapt his work, saying that Watchmen does things that can only be done in a comic book. But where there’s a will, there’s a way, and in 2009, Watchmen finally came to the big screen, directed by Zack Snyder.

I confess it took me a lot longer to write this review than I intended and that’s largely because I wasn’t sure how best to approach it. Snyder clearly has a lot of love and respect for the source material and tried his best to honour it as best he could. Snyder himself even said that he considers the film to be an advert for the book, hoping to get newcomers interested in the material. So how should I be looking at this film? As an adaptation or as an artistic tribute? More to the point, which of the three versions of the film should I be reviewing? The original theatrical cut, the director’s cut or the ultimate cut? Which best reflects Snyder’s artistic vision?

After much pondering, I decided to go with the director’s cut. The theatrical release was clearly done to make studio execs happy by keeping the runtime under three hours, but it comes at the cost of major plot points and character moments being chucked away. The ultimate cut however comes in at a whopping four hours and is arguably the most accurate to the source material as it also contains the animated Tales Of The Black Freighter scenes. However these scenes break the narrative flow of the film and were clearly not intended to be part of the final product, being inserted only to appease the fans. The director’s cut feels most like Snyder’s vision, clocking in at three and half hours and following the graphic novel fairly closely whilst leaving room for artistic licence.

Now as some of you may know, while I’m not exactly what you would call a fan of Zack Snyder’s work, I do have something of a begrudging respect for him due to his willingness to take creative risks and attempt to tell more complex, thought provoking narratives that don’t necessarily adhere to the blockbuster formula. Films like Watchmen and Batman Vs Superman prove to me that the man clearly has a lot of good ideas and a drive to really make an audience think about what they’re watching and question certain things about the characters. The problem is that he never seems to know how best to convey those ideas on screen. In my review of Batman Vs Superman, I likened him to a fire hose. Extremely powerful, but unless you’ve got someone holding onto the thing with both hands and pointing it in the right direction, it’s just going to go all over the place. I admire Snyder’s dedication and thought process, but I think the fact that his most successful film, Man Of Steel, also happens to be the one he had the least creative influence on speaks volumes. When he’s got someone to work with and bounce ideas off of, he can be a creative force to be reckoned with. Left to his own devices however, and his films tend to go off the rails very quickly.

Watchmen is very much Snyder’s passion project. You can tell a lot of care and effort went into this. The accuracy of the costumes, staging and set designs speak for themselves. However there is an underlying problem with Snyder trying to painstakingly recreate the graphic novel on film. While I don’t agree with the purists who say that Watchmen is ‘unfilmmable’, I do agree with Alan Moore’s statement that there are certain aspects of the graphic novel that can only work in a graphic novel. A key example of this is its structure. Watchmen has the luxury of telling its non-linear narrative over twelve issues in creative and unorthodox ways. A structure that’s incredibly hard to translate into any other medium. A twelve episode TV mini-series might come close, but a movie, even a three hour movie, is going to struggle due to the sheer density of the material and the unconventional structure. Whereas the structure of the graphic novel allowed Alan Moore to dedicate whole chapters to the origin stories of Doctor Manhattan and Rorschach and filling in the gaps of this alternate history, the structure of a movie doesn’t really allow for that. And yet Snyder tries really hard to follow the structure of the book even though it simply doesn’t work on film, which results in the movie coming to a screeching halt as the numerous flashbacks and origin stories disrupt the flow of the narrative, causing it to stop and start constantly at random intervals, like someone kangarooing in a rundown car.

Just as Watchmen the graphic novel played around with the common tropes and framing devices of comics, Watchmen the movie needed to play around with the common tropes and framing devices of comic book movies. To Snyder’s credit, there are moments where he does do that. The most notable being the first five minutes where we see the entire history of the world of Watchmen during the opening credits while ‘The Times They Are A-Changing’ is played in the background. This is legitimately good. It depicts the rise and fall of the superhero in a way only a movie can. I wish Snyder did more stuff like this rather than restricting himself to just recreating panels from the graphic novel.

Which is not to say I think the film is bad. On the contrary, I think it’s pretty damn good. There’s a lot of things to like about this movie. The biggest, shiniest gold star has to go to Jackie Earle Haley as Rorschach. While the movie itself was divisive at the time, Haley’s portrayal of Rorschach was universally praised as he did an excellent job bringing this extreme right wing bigot to life. He has become to Rorschach what Ryan Reynolds is to Deadpool or what Mark Hamill is to the Joker. He is the character (rather tragically. LOL). To the point where it’s actually scary how similar Haley looks to Walter Kovacs from the graphic novel. The resemblance is uncanny.

Another standout performance is Jeffery Dean Morgan as the Comedian. Just as depraved and unsavoury as the comic version, but Morgan is also able to inject some real charm and pathos into the character. You believe that Sally Jupiter would have consensual sex with him despite everything he did to her before. But his best scene I think was his scene with Moloch (played by Matt Frewer) where the Comedian expresses regret for all the terrible things he did. It’s a genuinely emotional and impactful scene and Morgan manages to wring some sympathy out of the audience even though the character doesn’t really deserve it. But that’s what makes Rorschach and the Comedian such great characters. Yes they’re both depraved individuals, but they’re also fully realised and three dimensional. They feel like real people, which is what makes their actions and morals all the more shocking.

Then there’s Doctor Manhattan, who in my opinion stands as a unique technical achievement in film. The number of departments that had to work together to bring him to life is staggering. Visual effects, a body double, lighting, sound, it’s a truly impressive collaborative effort, all tied together by Billy Crudup’s exceptional performance. He arguably had the hardest job out of the whole cast. How do you portray an all powerful, emotionless, quantum entity without him coming across as a robot? Crudup manages this by portraying Manhattan as being less emotionless and more emotionally numb, which makes his rare displays of emotion, such as his shock and anger during the TV interview, stand out all the more. It’s a great depiction that I don’t think is given the credit it so richly deserves.

Which leads into something else about the movie, which will no doubt be extremely controversial, but I’m going to say it anyway. I much prefer the ending in the film to the ending in the book.

Hear me out.

In my review of the final issue of Watchmen, I said I didn’t like the squid because of its utter randomness. The plot of the movie however works so much better both from a narrative and thematic perspective. Ozymandias framing Doctor Manhattan makes a hell of a lot more sense than the squid. For one thing, it doesn’t dump a massive amount of new info on us all at once. It’s merely an extension of previously known facts. We know Ozymandias framed Manhattan for giving people cancer to get him off world. It’s not much of a stretch to imagine the world could also buy that Manhattan would retaliate after being ostracised. We also see Adrian and Manhattan working together to create perpetual energy generators, which turn out to be bombs. It marries up perfectly with the history of Watchmen as well as providing an explanation for why there’s an intrinsic field generator in Adrian’s Antarctic base. It also provides a better explanation for why Manhattan leaves Earth at the end despite gaining a newfound respect for humanity. But what I love most of all is how it links to Watchmen’s central themes.

Thanks to the existence of Doctor Manhattan, America has become the most powerful nation in the world to the point where its disrupted the global balance of power. This has led to the escalation of the Cold War with Russia as well as other countries like Vietnam being at the mercy of the United States. It also allowed Nixon to stay in office long after his two terms had expired. The reason the squid from the book is so unsatisfying as a conclusion is because you don’t buy that anyone would be willing to help America after the New York attack. In fact it would be more likely that Russia and other countries might take advantage of America’s vulnerability. Manhattan’s global attack however not only gives the whole world motivation to work together, it also puts America in a position where they have no choice but to ask for help because it was they that effectively created this mess in the first place. So seeing President Nixon pleading for a global alliance feels incredibly satisfying because we’re seeing a corrupt individual hoist by his own petard and trying to save his own skin, even if it comes at the cost of his power. America is now like a wounded animal, and while world peace is ultimately achieved, the US is now a shadow of its former self. It fits in so perfectly with the overall story of Watchmen, frankly I’m amazed Alan Moore didn’t come up with this himself.

It’s not perfect however. Since the whole genetic engineering stuff no longer exists, it makes the existence of Adrian’s pet lynx Bubastis rather perplexing. Also the whole tachyons screwing with Doctor Manhattan’s omniscience thing still doesn’t make a pixel of sense. But the biggest flaw is in Adrian Veidt’s characterisation. For one thing, Matthew Goode’s performance isn’t remotely subtle. He practically screams ‘bad guy’ the moment he appears on screen. He has none of the charm or charisma that the source material’s Ozymandias had. But it’s worse than that because Snyder seems to be going out of his way to uncomplicate and de-politicise the story and characters. There’s no mention of Adrian’s liberalism or his disdain for Nixon and right wing politics. The film never explores his obsession with displaying his own power and superiority over right wing superheroes like Rorschach and the Comedian. He’s just the generic bad guy. And I do mean bad guy. Whereas the graphic novel left everything up to the reader to decide who was morally in the right, the film takes a very firm stance on who the audience should be siding with. Don’t believe me? Just look at how Rorschach’s death is presented to us.

It’s very clear while watching the film that Zack Snyder is a big Rorschach fan. He gets the most screen time and there’s a lot of effort dedicated to his portrayal and depiction. And that’s fine. There’s nothing necessarily wrong with that. As I’ve mentioned before in previous blogs, Rorschach is my favourite character too. However it’s important not to lose sight of who the character is and what he’s supposed to represent, otherwise you run the risk of romanticising him, which is exactly what the film ends up doing. Rorschach’s death in the graphic novel wasn’t some heroic sacrifice. It was a realisation that he has no place in the world that Ozymandias has created, as well as revealing the hypocrisy of the character. In the extra material provided in The Abyss Gazes Also, we learn that, as a child, Walter supported President Truman’s use of the atomic bomb in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and yet, in his adult life, he opposes Adrian’s plan. Why? What’s the difference? Well the people who died in Hiroshima and Nagasaki weren’t American. They were Japanese. The enemy. In Rorschach’s mind, they deserved to die, whereas the people in New York didn’t. It signifies the flawed nature of Rorschach’s black and white view of the world as well as displaying the racist double standards of the character. Without the context of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Rorschach’s death becomes skewed. This is what ends up happening in the movie. Rorschach removes his mask and makes a bold declaration to Doctor Manhattan, the music swells as he is disintegrated, defiant to the last, and his best friend Nite Owl screams in anguish and despair.

In fact the film takes it one step further by having Nite Owl punch Adrian repeatedly in the face and accuse him of deforming humanity, which completely contradicts the point of Dan Dreiberg as a character. He’s no longer the pathetic centrist who requires a superhero identity to feel any sort of power or validation. He’s now the everyman representing the views of the audience, which just feels utterly wrong.

This links in with arguably the film’s biggest problem of all. The way it portrays superheroes in general. The use of slow motion, cinematography and fight choreography frames the superheroes and vigilantes of Watchmen as being powerful, impressive individuals, when really the exact opposite should be conveyed. The costumes give the characters a feeling of power, but that power is an illusion. Nite Owl is really an impotent failure. Rorschach is an angry bigot lashing out at the world. The Comedian is a depraved old man who has let his morals fall by the way side so he can indulge in his own perverse fantasies. They’re not people to be idealised. They’re to be at pitied at best and reviled at worst. So seeing them jump through windows and beating up several thugs single handed through various forms of martial arts ultimately confuses the message, as does the use of gratuitous gore and violence. Are we supposed to be shocked by these individuals or in awe?

Costumes too have a similar problem. Nite Owl and Ozymandias’ costumes have been updated so they look more imposing, which kind of defeats the purpose of them. The point is they look silly to us, the outside observers, but they make the characters feel powerful. That juxtaposition is lost in the film. And then there’s the Silk Spectre. In the graphic novel, both Sally and Laurie represent the changing attitudes of women in comics and in society. Both Silk Spectres are sexually objectified, but whereas Sally accepts it as part of the reality of being a woman, Laurie resists it, seeing it as demeaning. The only reason she wore her revealing costume in A Brother To Dragons was because she knew that Dan found it sexually attractive and she wanted to indulge his power fantasy. None of this is touched upon in the film, other than one passing mention of the Silk Spectre porn magazine near the beginning of the film. There’s not even any mention of how impractical her costume is, like the graphic novel does. Yes the film changes her look drastically, but it’s still just as impractical and could have been used to make a point on how women are perceived in comic book films, but it never seems to hinder her in anyway. It’s never even brought up, which is ridiculous. Zack Snyder’s reinterpretation of Silk Spectre is clearly meant to inject some form of girl power into the proceedings, as she’s presented as being just as impressive and kick-ass as the others, when the whole point of her character was to expose the misogyny of the comics industry at the time and how they cater to the male gaze. Now don’t get me wrong, I’m not saying the graphic novel did it perfectly, but it did it a hell of a lot better than this.

Die hard fans have described the film over the years as shallow and ‘style over substance.’ I don’t think that’s entirely fair. It’s clear that Zack Snyder has a huge respect for the graphic novel and wanted to do it justice. Overall the film has a lot of good ideas and is generally well made. However, as much as Snyder seems to love Watchmen, it does seem like he only has a surface level understanding of it, hence why the attention and effort seems to be going into the visuals and the faithfulness to Alan Moore’s attention to detail rather than the Watchmen’s story and themes. While the film at times makes some good points about power, corruption and morality, it doesn’t go nearly as far as the source material does and seems to shy away from really getting into the meat of any particular topic. Part of that I suspect is to do with marketability, not wanting to alienate casual viewers, but I think a lot of it is to do with it simply being in the wrong medium. I personally don’t think you can really do a story as complex and intricate as Watchmen’s justice in a Hollywood film. In my opinion, this really should have been a TV mini-series or something.

So on the whole, while I appreciate Snyder’s attempt at bringing the story of Watchmen to life and can see that he has the best intentions in mind, I don’t think this film holds a candle to the original source material.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Captain Marvel (2019) and Demolition Man (1993)

I am marinating the portions of Dada’s Boys that I’ve read over the weekend. In the meantime, I wanted to practice some writing and ramble about two movies I’ve watched over the weekend.

Captain Marvel (2019), and

Demolition Man (1993)

((If anyone has a high-res copy of the poster...I’d be eternally grateful))

Incoherent rambling ahead

Summary: Captain Marvel wasn’t a good great movie (it was a fine movie); Carol Danvers is pretty cool but very similar to Cpt America’s character; looking forward to the second half of Infinity War; Demolition Man does a *lot* of things a *lot* better than Captain Marvel. Was Captain Marvel feminist? Lessons from good action movies.

I don’t explicitly mention plot points but /educated readers/ could probably deduce some spoilers both movies. (I’m being sarcastic. I definitely mention movie details without any regard to spoilers.)

I have a soft spot for both Marvel Studio movies and fun, cheesy, action flicks. I love the behemoth that MCU has become, something they could not have known when Iron Man was created 10 years ago... and I love the purity of action films - of good guys ‘beating up’ bad guys - and the heart actors and directors bring to it shown in movies like Die Hard. Some of the Marvel movies are right in that spot - and their strength shines more in the ‘character interaction’ department; whereas pure-action-comedy movies like Jackie Chan’s Hong Kong productions and The Matrix have great characters but the action sequences, where the actors themselves have to train at significant amounts, shine the most.

The more I think about Captain Marvel, honestly the more disappointed I am. Frankly for the big breaking International Women’s Day release it was not rich enough. I thought Black Panther had done marvelously (I still tear up thinking about the themes of disaphora in BP), nor was a pure comedic genius like Thor: Ragnorak .... It was a very, very, very average Marvel film. The first Ant Man is better than CM; the second Ant Man is not as good as CM.

Which is to say that CM is not a bad film, but unfortunately disappointing for what it was ‘supposed to be.’ I don’t feel bad thinking this way, because BP was a great success in my heart; it spoke to a universal theme while championing a targeted audience (of race and origin). As I am an immigrant, although I cannot associate with Black History Month, I can still relate to it deeply in terms of diasphora and displacement. (Wakanda forever!)

I’m urged to clarify again that CM was not a bad movie, but I think it failed because it placated a lot of the villains and conflict in favor of ~Carol Danvers~.

So, good parts of CM: Carol Danvers is pretty darn awesome. I really think that she brings hope to the Avengers, -- she symbolizes what the humans have better than any of the outer-Earth lives that are out their in the MCU: she gets back up. No matter what she’s told, whom she’s told by... She always gets back up. I did tear up here. I really did like that notion that she, and her humanity, is how the Avengers will win.

So.... That falls pale in her co-cast:

Nick Fury, who spends 75% of screentime cooing over a cat, and apparently too young to be the badass Fury that we know and love;

Kree mentor who tells her “u ahve 2 much emoshuns 2 be a gr8 kree”

Best friend whose character is only to tell Carol how great she is

Cat, saves the day probably more than she does

Somewhere between those lackluster sidekicks and Carol Danvers’ overpowered ‘superpower’ ... You basically get women are cool and funny and get over it as the central theme of the movie.

I think the “Carol Danvers gets back up” is problematic, because I read it in a very gender-neutral language (see above: I’m framing that as the HUMANITY’S reason to win, not WOMEN’s) -- potentially because this movie is situated in a world where the Avengers lost half of total lives in the universe... But also because the wOmyN aRe StRonG idea was so, SO obtuse, especially as response to CD’s Kree mentor (played by Jude Law) -- who, again, emphasizes how much weak Carol is because she lets emotions control her. Except it’s not about emotions. Emotions are not why Carol Danvers gains strength! (It’s her humanity!)

I think the emotion thing *could have* worked, had Carol not been very, I’d say extremely level-headed in spite of a lot of the weird stuff that happened through the movie. She never broke down, never threw a tantrum.... She was just a very secure person with a sense of humor that Fury even enjoyed.

So then, what was Jude Law even talking about? I find the “emotional is bad, logical is good” construct very gendered and extremely problematic, especially in our political/internet-driven social climate. In words of misogynists and keyboard warriors(who tend to be young males), being logical and rational is obviously superior; and emotional bad; and as a consequence many women (or emotional men) suffer through invalidation of their experiences. When Carol Danvers, as seen in the film, does *not* have issues controlling her emotions.... why does he even say that? Why is that even written in the script?

In short, .... Considering that this is supposedly Marvel’s stake on feminism (yikes, it didn’t even register to me as feminst) ... I have to borrow the words of this great Mashable article by Jess Joho:

The only thing that feels truly retro about Captain Marvel's '90s setting is its shallow take on feminism that we should be moving away from, not using as a crutch. It's not just that so many of the movie's heavy-handed Feminist Moments come across as disingenuous. Those moments also tap into an old conceit of equality as a sort of revenge fantasy, mixed with the undertone of a battle of the sexes. [...] The feminist-ish sentiment of "girls are just as good as boys" defines and measures women's empowerment as it compares to men. Consequently, it devalues and trivializes feminine power in its own right.

... so considering that this is, the first and only solo female movie in MCU...... They really, really could have done better. I hate to say this but (because MCU > DCEU), ...... Wonder Women did it a LOT better.

Onto Demolition Man. It’s past my bedtime so I’m going to just rush through random thoughts via bullet points:

Wesley. Snipes. (Probably doesn’t help that Blade is also one of my favorite movies.)

Sylvester Stalone was great in this movie. He had great form in all of the shots he was in. Commandeered every scene.

ALL OF THE CHARACTERS! They were so lively. Everyone had motivations that drove them, instead of being basically houseplants that can drive spaceships (ahem...CM...)

I definitely have another soft spot for movies with ridiculous plots. “LAPD gets cryofrozen as a criminal for failing to save citizens, but in tern DEMOLITION MAN-ing an entire complex throughout his career. When big bad evil Wesley Snipes gets parole, only one man can stop him --- the very Sylvester Stalone, The Demolition Man, who put him in jail!” “oh and this is a weird 2023 where you have to pay fines for cussing.”

Oddly enough this movie has a great example of ‘secure heterosexual male protagonist’ and ‘female love interest with her own motivations’.. They actually agree to (CONSENT TO!) make love, and she starts and finishes in her own terms.

Sylvester Stalone’s character is actually very caring and understands his role in the world he wakes up to; he is not at all gross (”back in my day” is never said) and he understands his position as a guest to all of this, while asserting his own views of morality onto the world.

Also I’m very upset that this movie achieved themes of displacement, utopia, and “who is the real bad guy?!” a lot, LOT, better than CM.

Denis Leary plays the rebel in the movie and also made this music video, which actually aligns a lot with my thesis interests (masculinity, prescribed notions of American life, suburbs....)

youtube

I just have to reiterate again that (1) Sylvester Stalone did not have to prove his masculinity to anyone, but his humanity is acknowledged by even the heroine in this character - (2) why must women still be *acknowledged* by man of our competence in 2019!?

OH, this movie makes SO MUCH BETTER 90s REFERENCES THAN CAPTAIN MARVEL!!! This is important. Captain Marvel makes 90s references as much as it nods to feminism. There’s a Blockbuster. And a Radioshack. Do they even realize those stuck around into the 2000s?

To conclude... I understand the constraints put onto Captain Marvel, sandwiched between freaking Infinity War 1 and Infinity War 2. But had Marvel Studios not learned their lesson from the tragedy of Age of Ultron? Even Joss Whedon, who arguably is a very well accomplished director, could not make AoU work. It was not a good movie. And he freaking set up the entire Avengers franchise!

I can’t know what lead to the underwhelming result that is Captain Marvel, but it is not a great product to stand on its own.

DEMOLITION MAN IS STILL RELEVANT! Captain Marvel will still only be relevant in the future if we don’t, as a society, move on from “girls can do anything boys can do” mentality.

3 notes

·

View notes

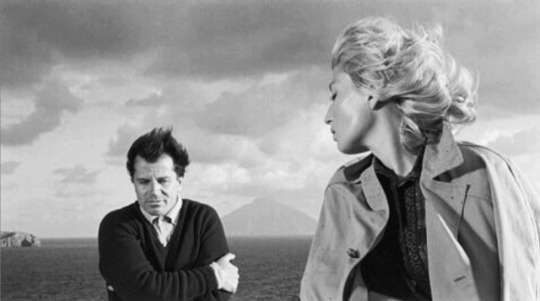

Photo

why should we be here talking, arguing? Believe me Anna, words are becoming less and less necessary; they create misunderstandings

eclisse inspirations, vol. IV

Michelangelo Antonioni’s Trilogy of incommunicability

part. 1 - L’avventura, 1960

When Michelangelo Antonioni’s L’avventura arrived in 1960 – amidst a tumultuous reception in Cannes that saw some disturbed audience members wanting to throw something at the screen – cinema was already changing in fundamental ways. The makers of individual, handmade films that had been institutionally kept out on the fringes (Stan Brakhage, Shirley Clarke, Norman McLaren, to name but three) were starting to draw more viewers and critical attention. The narrative feature film underwent a revision, from inside the nouvelle vague (Godard’s Breathless) and out (Agnès Varda’s first films, Alain Resnais’s Last Year in Marienbad). Meanwhile the Italian film world had already seen the old codes of neorealism swept away – much of it Antonioni’s own doing – and had moved towards a post-neorealist cinema liberated from melodrama and political ideologies, perhaps best exemplified in 1959 by Ermanno Olmi’s first feature Time Stood Still.

A new, maturing modernity became widespread in cinema. The years 1959 to 1960 can be identified as a world-historical moment for film. In line with the development of lenses, film stocks and new and smaller cameras (including a more ubiquitous use of 16mm), the modernism that took hold showed yet again the time lag after which cinema typically comes to embrace changes that have occurred first in other artforms: for instance, the radical overhaul of jazz by bebop; the transformation of the sound world of music by such figures as Edgard Varèse and Harry Partch; the abstract-expressionist movement in painting from Pollock to Rothko; the ‘new novel’ invading literature (on which Marienbaddrew, courtesy of a script by novelist Alain Robbe-Grillet).

In this exceptional moment, some of cinema’s old props were being kicked away, including Hollywood’s genre formulae, the three-act narrative structure, the privileging of psychology, the insistence on happy and ‘closed’ endings. But what did it mean to free oneself of the securing laws and traditions of genre, its capacity for creating worlds and codes? What did it mean to reject a storytelling architecture that had served dramatists well since Aeschylus? What kind of moving-image experience with actors could exist beyond psychology – which, after all, was still on the 20th century’s new frontier of science and society? What if endings were less conclusive, or less ‘satisfying’? These are the questions Antonioni confronted and responded to with L’avventura, the film that – more than any other at that moment – redefined the landscape of the artform, and mapped a new path that still influences today’s most venturesome and radical young filmmakers.

For some that film would instead be Breathless. Godard’s accidental discovery of the jump cut (courtesy of his editor) helped him rejig a more conventional yet sly imagining of the crime movie into a piece of radical art, a way of fracturing time as important as Picasso’s and Braque’s Cubist fracturing of space and perception. It’s also arguable that Godard had the more immediate impact, especially through the 1960s, since his taste for pop-culture iconography, graphic wordplay and politics positioned him a bit closer to the centre of the period’s cultural zeitgeist than Antonioni (despite the Italian’s subsequent ability to capture swinging London and The Yardbirds in 1966’s Blowup, and Los Angeles counterculture in 1970’s Zabriskie Point). Even a movie with huge pop figures and crossover attraction like Richard Lester’s A Hard Day’s Night (1964) would have been unthinkable without the example of Godard.

Yet I’d argue that L’avventura and Antonioni’s subsequent films – perhaps most importantly L’eclisse (The Eclipse, 1962) – have exerted a greater long-term impact (his effect on the generations after the 1960s is something I’ll consider later). One of L’avventura’s many remarkable qualities to note now is its staying power – its ability to astonish anew after repeated viewings. Many great films are of their moment, yet lessen over time. Here, the entrance of Monica Vitti, with her classically hip black dress and sexily tousled blonde mane, amounts to an announcement that the 60s have arrived; a lesser work with her in it would be no more than a key identifier of that moment.

It’s the film’s subtle straddling of an older world and a new one still in the process of defining itself – reflected immediately and perfectly in composer Giovanni Fusco’s opening title theme, alternating between nostalgic Sicilian strummings and nervous, creeping percussive beats – that establishes its rich, unending landscapes of physical reality and the mind. This is part of the film’s timelessness, within an absolutely contemporary / modern setting. The early images of L’avventura trace a parting of the generations, as Anna (Lea Massari) – seemingly the film’s central character – tells her wealthy Roman father that she’s going away on a holiday to Sicily with girlfriend Claudia (Vitti), then seen very much on the periphery of the action, tagging along. But after Anna inexplicably disappears during a boat trip to an uninhabited island, it is Claudia who moves to the centre of the narrative – and into the affections of Anna’s architect boyfriend Sandro (Gabriele Ferzetti) – as attempts to find Anna gradually peter out.

What makes L’avventura the greatest of all films, however, is its assertion, exploration and expansion of the concept of the ‘open film’. This had been Antonioni’s great project ever since he started out as a filmmaker after an extremely interesting career as a critic (like Godard). His early documentaries, such as The People of the Po (Gente del Po, 1947), and his earliest narrative films, such as the astonishing Story of a Love Affair (Cronaca di un amore, 1950), suggest an artist pulling against what he perceived as the constraints of neorealism towards an openness based on a heightened perception of constant change – a dynamic that was for him the fundamental quality of the post-war world.

A NEW QUESTION

For Antonioni, the issues of neorealism were essential, in that they gave him an aesthetic base from which to launch. The People of the Po is an early neorealist work, both in its submersion in unvarnished realism and its interest in the lives of working people, but it also works against the predominant tendency in neorealism to project sympathy and sentimentality. By the time of Story of a Love Affair, teeming with characters from the upper and middle classes, his was not a class-based cinema; it offered instead a broader perspective – observant, distanced, occasionally unsympathetic. It reached into a more modern realm than neo-realism, a realm that had no name for it – and in fact still doesn’t.

Antonioni was never a leader – nor even part – of a movement. That’s partly because with each successive film he constantly redefined his approach. Roland Barthes, in his profoundly perceptive and concise 1980 speech honouring Antonioni, identified the process this way: “It is because you are an artist that your work is open to the Modern. Many people take the Modern to be a standard to be raised in battle against the old world and its compromised values; but for you the Modern is not the static term of a facile opposition; the Modern is on the contrary an active difficulty in following the changes of Time, not just at the level of grand History but at that of the little History of which each of us is individually the measure. Beginning in the aftermath of the last war, your work has thus proceeded, from moment to moment, in a movement of double vigilance, towards the contemporary world and towards yourself. Each of your films has been, at your personal level, a historical experience, that is to say the abandonment of an old problem and the formulation of a new question; this means that you have lived through and treated the history of the last 30 years with subtlety, not as the matter of an artistic reflection or an ideological mission, but as a substance whose magnetism it was your task to capture from work to work.”

L’avventura builds on the work and experiences of Antonioni’s previous decade, which saw him working through his doubts about genre (film noir in Story of a Love Affair, backstage drama in La signora senza camelie, 1953); about narrative form (the counter-intuitive three-part structure of I vinti, 1952); his love of writer Cesare Pavese (author of the source novel for 1955’s Le amiche) – as important a literary voice to Antonioni as Cesare Zavattini was to the hardcore neorealists. And add to this his growing interest in temporality, the emptied-out frame, the composition that maintains both precision and an expansive gaze that treats bodies, buildings and landscapes with equal importance.

With only a few filmmakers (Mizoguchi, Renoir, Dreyer, von Sternberg, Resnais, Olmi, Kubrick, and more recently Costa, Alonso and Apichatpong) is there such a visible, constant seeking of artistic purpose through the process of each successive film – a striving, a refinement. Antonioni’s 1950s work represents one of the most fruitful directorial decades to watch of any filmmaker. Already in some ways a master in 1950, he proceeded to question his own positions with each film, as if the doubts he had about the state of the post-war world resided, originally, in himself, and then fanned out to the making of the work itself, so that the expression of mortality (most explicitly conveyed in a Pavese adaptation such as Le amiche) inside the film was part and parcel of the director’s own tentative stance. (Tentato suicido/Tentative Suicide is the title of Antonioni’s segment in the 1953 omnibus film L’amore in città.)

These were not only cerebral matters – though the intellectual currents running underneath these films and under the neorealist movement preceding them were crucial to their fecundity – but real concerns rooted in the hard factors that faced any Italian filmmaker trying to get a project off the ground. Antonioni’s tentativeness – a constant fascination to his supporters in the French critical community, and an irritation to many of his Italian contemporaries – was partly based on the tentativeness of Italian film production itself. In almost no case during the 1950s did he encounter a smooth pre-production, firm financial backing or drama-free production periods. The typically poor performance of his films at the box office did little to enamour him to distributors and producers, though in the then nascent world of the auteur film business, it helped enormously that his films did well – even smashingly well – in Paris.

After the commercial failure of Il grido (1957) and an initially limp critical response, Antonioni seriously considered abandoning the cinema altogether, and returned to the theatre, where he had worked in the early years of his career. Even when he did come back to film, to shoot L’avventura, all of his worst concerns came back to haunt him. Already shaky producers bailed out mid-shoot as their company, Imeria, went bankrupt, leaving the crew literally high and dry on the desert island of Lisca Bianca, without sufficient food and water, in a hair-raising episode that makes Coppola’s misadventures filming Apocalypse Now in the Filipino jungle sound like a stroll on the beach.

SURPASSING MYSTERIES

This context, in all its intellectual and practical dimensions, is crucial to comprehending the massive achievement that L���avventura represents. How a film of such constant perfection could even be made under such dreadful conditions is, for me, one of the surpassing mysteries of film history. Viewed in isolation (and aren’t almost all films, even more now in our isolated viewing environments?), L’avventura can superficially be seen as magnificently beautiful in its constant chain of stunning black-and-white images from cinematographer Aldo Scavarda (with whom Antonioni had never previously worked, and never would again).

L’avventura is populated by good-looking actors oozing sex appeal. Monica Vitti, for one, had never had a starring film role before, but with her smouldering presence it was she – as much as Sophia Loren or Ingmar Bergman’s ensemble of intelligent and worldly actresses – who set the standard and the look for the new, sexualised European movie star that was key to the successful foreign-film invasion that hit English-language shores (and was perceived as such a threat by LBJ and his White House crony Jack Valenti that they set up the American Film Institute as a nationalist bulwark against the foreigners supposedly taking over US cinemas). For New York downtown hipsters, London cosmopolitans and Paris cinephiles alike, the combination of serious cinema and sexual beauty was simply too much to pass up.

All that may be why L’avventura had its immediate impact. (A special jury prize from Cannes, after all that booing and hissing, also didn’t hurt.) But the endurance of the film, residing crucially in its conceptual openness, describes a pathway that cinema has been exploring and testing ever since. Much as Flaubert’s novels and Beethoven’s symphonies, concertos and string quartets are continually regenerated by way of the new directions they paved, and the new generations of work following such directions, so Antonioni’s work – and L’avventura in particular – is regenerated by the subsequent cinema that came in its wake.

As Geoffrey Nowell-Smith observes in his essential study of the film, the periphery in Antonioni is of absolute importance, for this is where the sense of drift in his mise-en-scène and narratives resides – a de-centred centrality. No filmmaker before Antonioni, not even the most radical visionaries like Vigo, had established this before as a part of their aesthetic project. In the early scenes when Anna visits Sandro, or when they join their holiday boating group, Vitti’s Claudia remains for a long time on the outside looking in, marginalised, seemingly unimportant. And yet there is something in her nervous gaze, her subtle physical gestures, that makes her impossible not to notice, especially in contrast to Anna’s inner tension and outward unhappiness – an unhappiness she can’t identify, even in private to Claudia.

These are most certainly not Bergman women, forever examining themselves, forever able to articulate the exact words in whole spoken paragraphs about their state of mind, their relationship with God. For one thing, in Antonioni, God doesn’t exist. The state of the world is one of humans searching for some kind of connection amidst a disinterested nature; the island on which the floating party lands is both exotically remote and barren, like a volcano frozen during eruption. The landscapes in L’avventura have been interpreted in a number of different ways that testify to the film’s Joycean levels of readings: from Seymour Chatman’s insistence on metonyms for his reading of what he calls Antonioni’s “surface of the world”, to Gilberto Perez’s more valuable view of the work in his extraordinary film study The Material Ghost, across a whole range of possible interpretations, from the literary to the visual. For me, however, it’s always tempting to see these people – on this island, at that moment – as the last humans on earth.

In L’avventura, more than any film before it had ever dared, the centre will not hold. The open film is a fluid thing, pulsating, forever changing, shifting from one centre to another, not quite beginning and not quite ending (or at least beginning something new in its ‘ending’). Anna, the centre, vanishes, with no visual or verbal clues to trace her by, except rumours of sightings. She was in effect the glue that held the party together, having helped bring Claudia in closer to her circle of friends – and to Sandro. But with Anna’s disappearance, the film alters shape in front of us; a sudden absence actually expands the film’s eye. Individual shots become more extended and prolonged, the sky and land grow larger, the elements become more tangible (clouds, rain, harsher sun).

HERE AND NOW

What’s even more disturbing is that nothing happens – no discovery, no evidence, no detective work and, finally, no memory. L’avventura is, in part, the story of how a woman is forgotten, to the extent that long before the film is done, Anna is less than a trace on a page, a ghost or a photo in an album. A more sentimental filmmaker or a Hollywood studio would have ensured that Anna lived on through Claudia and Sandro’s love affair and possible union. But here, after a while, they don’t speak of Anna anymore. She gradually fades, which is what happens to the dead as regarded by the living (not that Anna is necessarily dead; the film neither encourages nor discourages the suggestion). Although their joint actions ostensibly trace an effort to collect any information on Anna’s whereabouts, Antonioni suggests that the activity of Claudia and Sandro isn’t nearly as important as their time together in this moment, in this or that place.