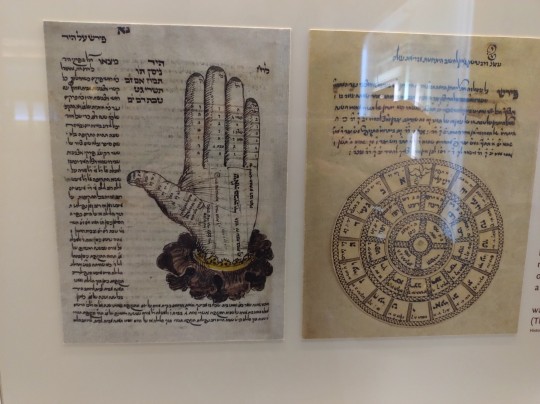

#yiddish culture

Text

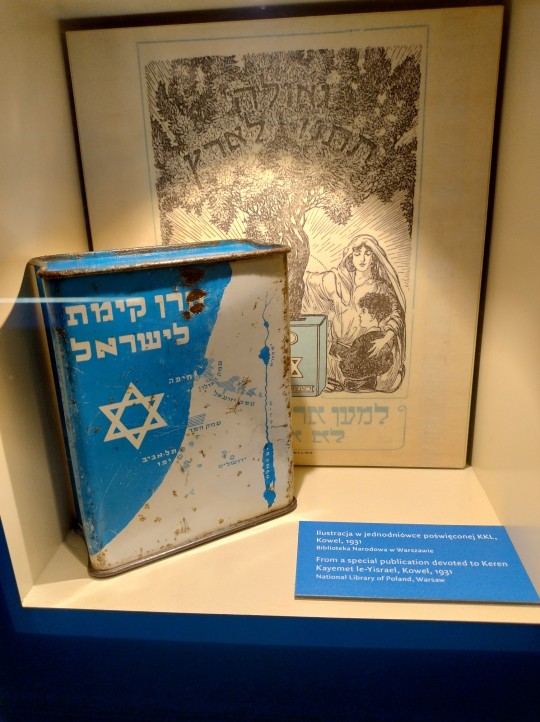

Polin museum of the History of Polish Jews, Warsaw, Poland

It's a great place, very worth seeing

#jidysz#jewish culture#jews in poland#yiddish culture#jewish history#jewish#jews#ashkenazi culture#ashkenazi jews#ashkenazi#synagogue#jeshiva#kabala#jewish amulet#jewish talisman#canopy#jewish wedding#polin#polin museum#warsaw#poland#polish jews#jewish museum

218 notes

·

View notes

Text

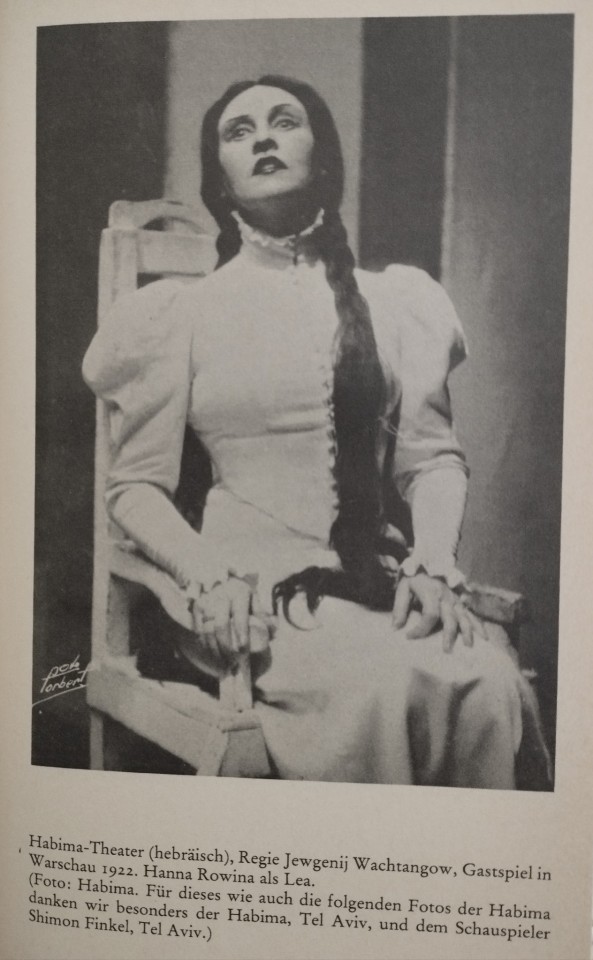

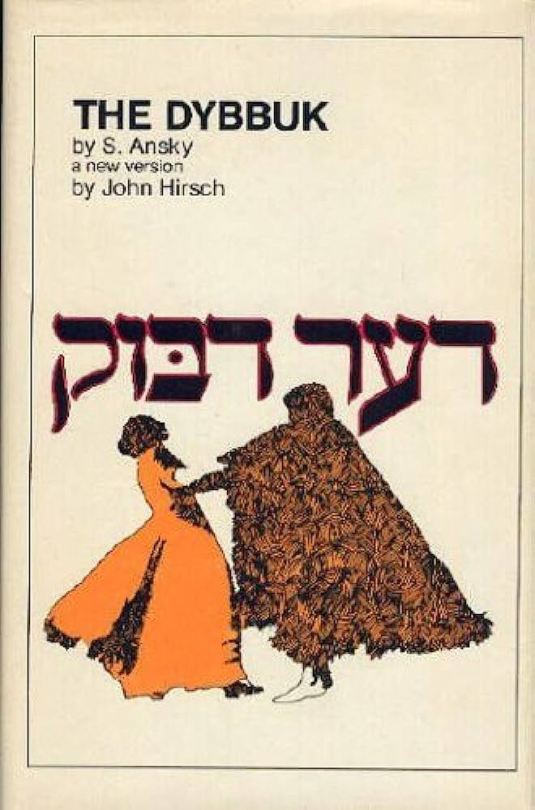

Hanna Rowina as Lea in "The Dybbuk" 1922

#yiddish theater#yiddish culture#the dybbuk#an-ski#hanna rowina#yiddish literature#1920s#photo from my german dybbuk book#i could read it in russian at least

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm in love with the fact that Dovid Katz's English-Yiddish dictionary translates "cancel culture" as חרם־קולטור (kherem-kultur).

#yiddish#dovid katz#yiddish cultural dictionary#cherem#kherem#judaism#jewish culture#yiddish culture#cancel culture

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Yentl—you have the soul of a man.”

“So why was I born a woman?”

“Even Heaven makes mistakes.”

Yentl, the Yeshiva Boy by Isaac Bashevis Singer

#jumblr#jewish#jews#nesyapost#judaism#jewish culture#jewish reading#Jewish books#yiddish#yentl the yeshiva boy#yentl#isaac bashevis singer#transgender

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

If you want to code-switch so often that you are nearly incomprehensible to goyim, here is a list of my favorite and most-used Jewish terms:

Schvitzing - Sweating. (Ex: "I'm schvitzing so much it's showing through my clothes.")

Schlep - A tedious and long journey, depending on usage it can mean that you were carrying something. (Ex: "I had to schlep all the way across campus, my backpack was so heavy." Usually denotes a long walk, but other forms of transportation are acceptable too. "You drove all the way to New York from Florida? That's quite the shlep.")

Shtati - Something really cool. (Ex: "I visited my friend's place and they had a shtati mezuzah!")

Neshama - Soul. (Ex: "Mazel tov on your conversion, you have such a strong Jewish neshama!")

Balagan - A big mess, chaotic, confusing (Ex: "Moshe forgot to bring challah for shabbat dinner, and it turned into this big balagan")

Achi/Achoti - "Achi" literally means "my brother," but can also be used like bro or dude, "achoti" is the feminine equivalent meaning "sister"

Yalla - Come on, let's go (Ex: "Yalla yalla, you're going to make us late again")

Mishpacha - Family. Doesn't have to be literal blood relatives, usually a sign of warmth or friendship. (Ex: "I care about every Jew, they're all my mishpacha.")

Pshhh - Interjection sound, to express respect or agreement with what someone is saying, but can also be playfully poking fun at someone taking themselves too seriously, can be used sarcastically.

Achla - amazing, awesome, great, the best (Ex: "You graduated from university? Achla!")

Sheina Punem (Shayna Punim) - Pretty face (Ex: My bubbe kept pinching my cheeks and calling me a sheina punem) Can be used ironically, in which case it means "a disgrace."

Ahavat Yisrael - to love your fellow Jew (Ex: "I firmly believe in ahavat yisrael, even if it's hard sometimes.")

Schande - Shame, dishonor among the nations, meaning a Jew who represents Jews badly, a serious insult. (Ex: "He's a schande, he feeds into antisemitic stereotypes.")

Schmutz - Dirt, stain. (Ex: "Use your napkin, you've got schmutz on your face.")

Amalek - Any enemy of the Jewish people. ("[Fill in blank] is the modern Amalek, they hate the Jews.")

Lanceman/Landsmen - Two jews from the same place, a point of connection between two Jews who now live far away from their hometown. (Ex: "Your grandma is from Crown Heights? Mine too, our grandparents are landsmen!")

Goyisch - Something not Jewish (Ex: "I don't listen to Taylor Swift, her music is too goyisch for me.")

Goyischekop/Goyische-kop - Goyisch head, a jew who thinks/sounds like a non-jew. (Ex: "How could you say about your fellow Jew? Do you have a goyische-kop or something?")

Kindaleh/Kinderlach - Little children (Ex: "I passed by the school and saw the kindaleh on the playground, they're so cute!")

Chamud/Chamuda/Chamudi - Sweetie, cutie, usually aimed at children, but can be a term of endearment between a couple. Can be condescending when said rudely to another adult, like "Sweetheart" can be in English. (ex: "Goodnight, Chamudi. I can't wait to see you tomorrow.")

Daven - to pray ("Are you going to join us for davening?")

Frum - A religiously observant Jew. ("He's frum, he davens three times a day.")

Treif - Unkosher, generally something not good, doesn't have to literally refer to a food. ("I trained my dog to stop barking when I say 'treif!'.")

Bubkis - Zero, nothing, nada ("Moshe got a gift from bubbe and I got bubkis.")

Kvetch - To complain ("I'm just kvetching, I'm not that upset about it.")

Kvell - Extreme pride. ("I heard your daughter made it into her top school, you must be kvelling!")

Mensch - A good, admirable person. ("He volunteers every week, he's a mensch.")

Chillul HaShem - Disgracing God's name, someone who does something that makes Jews look bad.

Kiddush HaShem - Something that sanctifies God's name, brings honor to God. ("I love seeing you wear a kippah, it's a kiddush HaShem!")

Bubbe meise - Little white lies ("He told his teacher a bubbe meise about his dog eating his homework.")

I should acknowledge that these are mostly Yiddish words, as my experience is primarily with Ashkenazi Jews. If you would like to add common slang from your community (like Ladino phrases, Judeo-Arabic, Italki, etc) I would love to learn about them!

#there are so many other words but i use these all the time#add whatever you want!#jumblr#frumblr#jewblr#yiddish#hebrew#jewish#jewish culture#j tag#jew tag

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Anti-Zionist Yiddish song, "Oh, You Foolish Little Zionists".

157 notes

·

View notes

Text

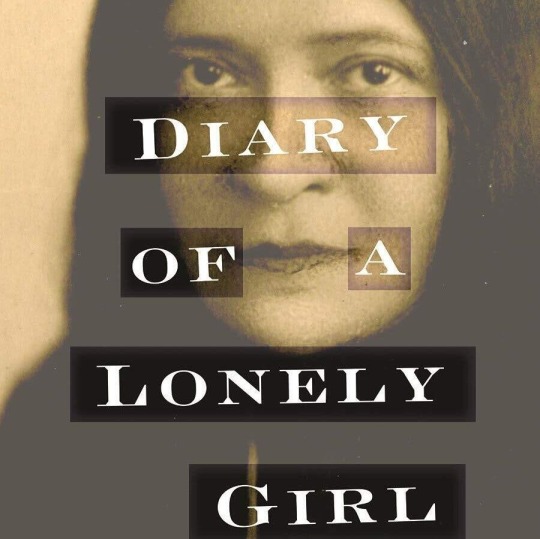

Works written decades ago, often by female Jewish immigrants, were dismissed as insignificant or unmarketable. But in the past several years, translators devoted to the literature are making it available to a wider readership. -

By Joseph Berger

Feb. 6, 2022

In “Diary of a Lonely Girl, or the Battle Against Free Love,” a sendup of the socialists, anarchists and intellectuals who populated New York’s Lower East Side in the early 20th century, Miriam Karpilove writes from the perspective of a sardonic young woman frustrated by the men’s advocacy of unrestrained sexuality and their lack of concern about the consequences for her.

When one young radical tells the narrator that the role of a woman in his life is to “help me achieve happiness,” she observes in an aside to the reader: “I did not feel like helping him achieve happiness. I felt that I’d feel a lot better if he were on the other side of the door.”

In a review for Tablet magazine, Dara Horn compared the book to “Sex and the City,” “Friends” and “Pride and Prejudice.” Though it was published by Syracuse University Press in English in 2020, Karpilove, who immigrated to New York from Minsk in 1905, wrote it about a century ago, and it was published serially in a Yiddish newspaper starting in 1916.

Jessica Kirzane, an assistant instructional professor of Yiddish at the University of Chicago who translated the novel, said that her students are drawn to its contemporary echoes of men using their power for sexual advantage. “The students are often surprised that this is someone whose experiences are so relatable even though the writing was so long ago,” she said in an interview.

Yiddish novels written by women have remained largely unknown because they were never translated into English or never published as books. Unlike works translated from the language by such male writers as Sholem Aleichem, Isaac Bashevis Singer and Chaim Grade, Yiddish fiction by women was long dismissed by publishers as insignificant or unmarketable to a wider audience.

But in the past several years, there has been a surge of translations of female writers by Yiddish scholars devoted to keeping the literature alive.

Madeleine Cohen, the academic director of the Yiddish Book Center in Amherst, Mass., said that counting translations published or under contract, there will have been eight Yiddish titles by women — including novels and story collections — translated into English over seven years, more than the number of translations in the previous two decades.

Yiddish professors like Kirzane and Anita Norich, who translated “A Jewish Refugee in New York,” by Kadya Molodovsky, have discovered works by scrolling through microfilms of long-extinct Yiddish newspapers and periodicals that serialized the novels. They have combed through yellowed card catalogs at archives like the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, searching for the names of women known for their poetry and diaries to see if they also wrote novels.

“This literature has been hiding in plain sight, but we all assumed it wasn’t there,” said Norich, a professor emeritus of English and Judaic Studies at the University of Michigan. “Novels were written by men while women wrote poetry or memoirs and diaries but didn’t have access to the broad worldview that men did. If you’ve always heard that women didn’t write novels in Yiddish, why go looking for it?”

But look for it Norich did. It has been painstaking, often tedious work but exciting as well, allowing Norich to feel, she said, “like a combination of sleuth, explorer, archaeologist and obsessive.”

“A Jewish Refugee in New York,” serialized in a Yiddish newspaper in 1941, centers on a 20-year-old from Nazi-occupied Poland, who escapes to America to live with her aunt and cousins on the Lower East Side. Instead of offering sympathy, the relatives mock her clothing and English malapropisms, pay scant attention to her fears about her European relatives’ fate and try to sabotage her budding romances.

Until Norich’s translation was published by Indiana University Press in 2019, there had been only one book of Yiddish fiction by an American woman — Blume Lempel — translated into English, Norich said. (Two non-American writers had been translated: Esther Singer Kreitman, the sister of Isaac Bashevis Singer, who settled in Britain, and Chava Rosenfarb, a Canadian who translated herself.)

The new translations are stirring a smidgen of optimism among Yiddish scholars and experts for a language whose extinction has long been fretted over but has never come to pass. Yiddish is the lingua franca of many Hasidic communities, but their adherents rarely read secular works. And it has faded away in everyday conversation among the descendants of the hundreds of thousands of East European immigrants who brought the language to the United States in the late 19th century.

The new translations are being read by people interested in everyday life in East European shtetls and immigrant ghettos in the United States as told from a woman’s perspective. They are also being read by students at the nation’s two dozen campuses with Yiddish programs. “Students were often surprised by how unsentimental these female novelists are, how wide-ranging are their themes, and how frank they are about female desire,” Norich said.

With a grant from the Yiddish Book Center, a 42-year-old nonprofit that seeks to revitalize Yiddish literature and culture, Norich is now translating a second novel: “Two Feelings,” by Celia Dropkin (1887-1956), a Russian immigrant who was admired for her erotically charged poems but never known as a novelist.

“Two Feelings” had been serialized in The Yiddish Forward in 1934 and then forgotten. It tells the story of a married woman who struggles to reconcile her feelings for, as Norich put it, a “husband she loves because he is a good man, and a lover she loves because he is a good lover though not a good man.”

One recent volume, “Oedipus in Brooklyn,” is a collection of stories by Blume Lempel (1907-99), the daughter of a Ukrainian kosher butcher. After spending a decade in Paris, she, her husband and their two children immigrated to New York in 1939, where she began writing for Yiddish newspapers.

In an introduction, her translators, Ellen Cassedy and Yermiyahu Ahron Taub, describe Lempel as “drawn to subjects seldom explored by other Yiddish writers in her time: abortion, prostitution, women’s erotic imaginings, incest.” Her sentences, they add, “often evoke an unsettling blend of splendor and menace.”

In promotional copy for the book, Cynthia Ozick called it “a splendid surprise” and asked: “Why should Isaac Bashevis Singer and Chaim Grade monopolize this rich literary lode?”

The recent books have mostly been published by academic presses in small runs, many of them financed by fellowships and stipends from the Yiddish Book Center. Despite the books’ contemporary themes, said Cohen, the center’s academic director, it has been an uphill battle to persuade mainstream trade publishers to acquire titles by women writers who are generally unknown and previously untranslated.

The scholars work independently, though they occasionally meet at conferences and panel discussions. Their life stories offer a window into the evolution of Yiddish.

Kirzane learned the language not in her childhood home but at the University of Virginia and in a doctoral program at Columbia University. Norich, the daughter of Yiddish-speaking Holocaust survivors from Poland, was born after the war in a displaced persons camp in Bavaria and was raised in the Bronx, continuing to speak Yiddish with her parents and brother.

When her daughter Sara was born, she made an effort to speak only Yiddish to her but gave up when Sara was 5. “You need a community to have a language grow,” she said.

These translators believe that the newly translated novels by women will enrich the teaching of Yiddish. Yiddish is, after all, called the mamaloshen — mother’s tongue — and a woman’s perspective, they said, has long been missing.

103 notes

·

View notes

Text

GOYIUM STOP USING THE WORD "ZIONISM", IT IS OUR WORD, IT BELONGS TO ONLY JEWS! IT IS NOT AN ENGLISH WORD, WE TELL YOU WHAT IT MEANS AND YOU IGNORE US. SO YOU KNOW YOU ARE STEALING OUR CULTURE, RIGHT? HIJACKING IT THEN USING IT TO SUPPORT TERRORISM AND MAKE YOU FEEL LESS GUILTY YOU FUCKING CHAZZERS!

For people who hate us soo much, they sure like to appropriate our culture but at the same time ignore those who actually practice and live the culture.

#antisemitism#tw antisemtism#jumblr#jewish#am yisrael chai#two state solution#i stand with israel#fuck hamas#i/p war#fuck off all of you#Fuck all the goyium who do this shit#I bet you'll look up the name I called you#That's the most of our culture you'll know of#Yiddish words#Pro palistine people you are the reason people are dying#you guys fail#Dear antisemitic leftists#Dear antizionist goyium#Why don't you go over and protect those people then?#If you like it so much and it's so great go live there#Stupid idiots#Ashkanz jew

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hey friends!

Yiddishland California is a cultural center and museum that puts on excellent classes and events, including Yiddish Theater classes, Intermediate Yiddish reading circles, and even beginner's Yiddish yoga! They are committed to keeping the wonderful and vibrant language alive, including the culture and community that surrounds the language.

They are in trouble! There was some sort of issue with being able to stay in their location, so they need to raise $100k by the end of the month to stay open!

Please join me in donating (Here). I gave my tzedakah this month to them, and I hope you do too!

If you're in the Southern California area, they're having a relocation party on January 21st, 2024 from 5-8pm. Come visit to see great art and support such a great organization!!

For the rest of us that can't get down to California and want to support not just by donating, please consider buying something from their Etsy shop! They have a bunch of rare books and vinyl and your purchase will help the organization!

#Yiddish#Yiddishland#Yiddishland California#jublr#jumblr#judaism#jewish#langblr#I found this place and my mum got so excited that she might finally be able to connect with her parents (z''l) through a yiddish theater c#lass but then when I called to see when the next class was they told me about their deadline for the location#culture#theatre#theater#Yiddish theater#donate#please donate

74 notes

·

View notes

Note

This is just terminology but regarding asking goyim to ID ourselves as such, may I ask if there's a specific reason you prefer that phrasing? Asking because I've previously heard that hearing someone self-describe as goyische can be a bit jarring due to Connotations from white supremacists "reclaiming" the term (scarequotes bc that's obviously not how reclamation works) so I'm wondering if you have an alternate perspective I should be taking into account or if it's just like, personal preference/not that deep.

Ah! @faggotry-enjoyer, My friend! I did not see this message from you until today! My deepest apologies!

I didn’t mean that every goy had to specifically call themselves goy. I’m just descended from Hungarian, Russian, French, and Mongolian Yiddish speakers and that’s more familiar a term to me than “gentiles.”

Personally, I’ve always found “gentiles” a little awkward as a term anyway. As I’ve stated repeatedly, goy is a fully neutral word with no positive or negative connotations. But the word “gentile” seems to have a weirdly positive connotation that I find off-putting. It seems far too close to the word “gentility” for me.

It feels like “gentile” is a person of “the gentility,” thus inherently socially, behaviorally, and aesthetically superior to non-gentiles (aka Jews). Perhaps this is just because of my relationship to Hebrew (and its use of root constructions that convey connotations in the base structure of the word) that this seems to be a term that is inherently critical of Jews in a pretty blatant way. But it always seems just…idk. Uncomfortable for me to use I guess. It feels like I’m putting myself down to elevate someone else and acknowledging their inherent superiority over me.

That said, I am in no way suggesting that this is how all Jews relate to this word. I have studied Hebrew since I was very young (I’m not a fluent speaker anymore, but I was once), and I’m a writer and love words and etymologies. It is extremely likely that I am thinking more about this than someone else would or does.

So, I say goy because it is the most neutral to me. It doesn’t convey that I’m better than a goy or that a goy is better than me.

When I said “goyim identify yourself as such,” I meant more generally, “if you’re not Jewish, please indicate that in your reblog or tags when reblogging from a Jewish person.”

And to anyone who is new to my blog, the reason I asked goyim to do this is because Jews feel very alone and hated right now and a very easy way to help us feel better is to just let us know that someone outside of our community sees and hears us. It so very often feels like we are shouting from inside a soundproof room and we can only hear and be heard by each other.

There are so very few Jews left in the world. It is simply impossible for us to survive if we advocate for ourselves alone. We need goyische voices alongside our own if we hope to be heard at all amongst those who outnumber us.

One thing about Jewish culture though, we all disagree a lot about a lot of things. Someone probably does find it offensive to self-label as a goy. Someone else probably finds it offensive to reject the idea of self-labeling as a goy.

However, by and large, I think most Jews won’t be concerned that you’re appropriating our language and culture if you are using our language to identify yourself as someone who supports our culture. Yiddish isn’t a religious language, but a cultural one. While Judaism is a closed-practice religion, Yiddish is the language of our culture in exile. It is the language we used while existing in a goyische world that was and remains hostile toward Jews.

I think, personally, that if you’re not using our language to demean us, it’s not off limits. Like, call yourself a goy! You are one! It’s not a bad thing! But, like, don’t call Jews you disagree with schmucks or something like that. And, obviously, if someone is antisemitic then I do not want them using Yiddish at all.

If someone wants to condemn our culture, then I loathe the idea of them picking out the parts they can use for their own purposes. If you reject an entire culture, you do not get access to the parts of that culture you like, imho.

So, I guess (in answer to your question) it is personal preference but is also that deep. Jewish culture is old, deep, and complex. I'd never speak for other Jews, and I'm sure plenty disagree with me on this. But I have personally never heard of a Jewish person offended that a goy calls themselves a goy. Personally, I find it endearing.

66 notes

·

View notes

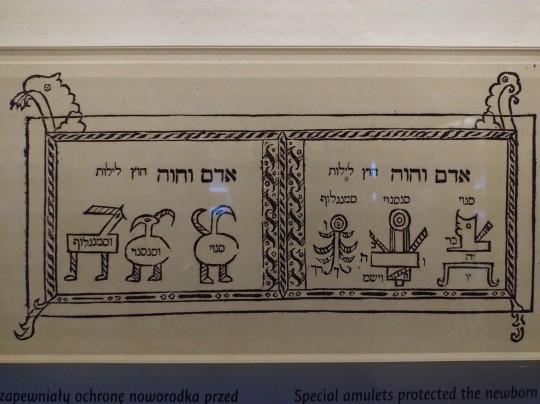

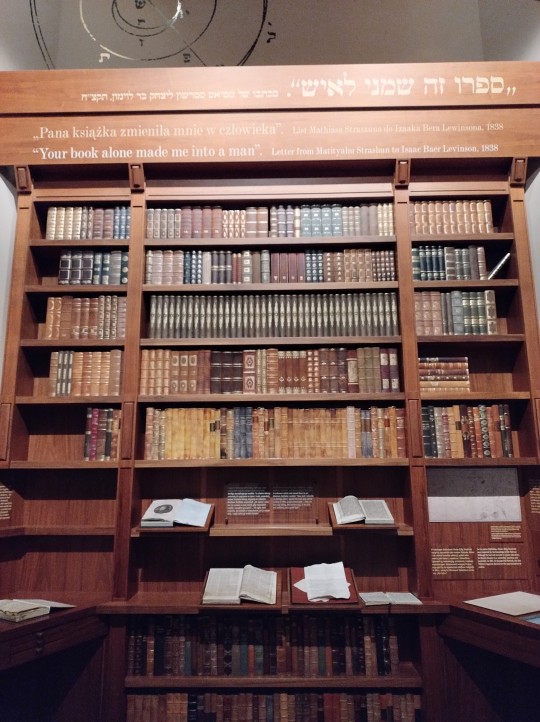

Text

Polin museum of the History of Polish Jews, Warsaw, Poland

#jidysz#jewish culture#jews in poland#yiddish culture#jewish history#israel#am yisrael chai#aliyah#ashkenazi culture#ashkenazi jews#ashkenazi#jews#Jewish#pushke

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

THIS IS THE FUNNIEST FUCKING THING IVE SEEN ALL WEEK OY

#batman#dc#Harley Quinn#bruce wayne#batfamily#TikTok#part four of me just putting funny batman TikToks on here until someone tells me to stop#Jewish Harley Quinn??#Yiddish#jewish culture

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Scene from the most famous Yiddish play The Dybbuk by the Vilner Trupe. 1910s.

#jumblr#jewish#jews#nesyapost#jewish history#jewish culture#yiddish#Poland#Eastern Europe#jewish art#Jewish theater#Jewish actors#the dybbuk#1910s#yiddish folklore#Jewish folklore#ashkenazim#ashkenazi#photography#vintage photography

661 notes

·

View notes

Text

Has anyone else noticed the weird appropriation of Yiddish for specifically anti-zionist spaces? It makes me deeply uncomfortable.

#its gross#why are you all so fucking weird about jews#why cant you be normal#these same people are like “jews are a diaspora people so thats why we learn yiddish'#without thinking or asking where the diaspora is from#because you cant have a diaspora without a point of origin.....#and then they still deny jews are indigenous to israel#so they dont care about most mizrahi jews who literally live there and have forever#but then they kind of have this weird fascination with yemeni jewish culture#and like exoticize (?) Mizrahi jews#but not if youre from israel then youre immoral and evil

279 notes

·

View notes

Note

Jewish culture is being super excited to find a platform to learn Yiddish on because even the platforms that boast about their plethora of languages do not have it. And it's free!! Probably still going to take a proper class on it as what I've found doesn't have grammar as thoroughly explained as I would like.

(its mangolanguages.com in case you're wondering)

thank you for sharing the site op <33

45 notes

·

View notes