#zitkala sa

Text

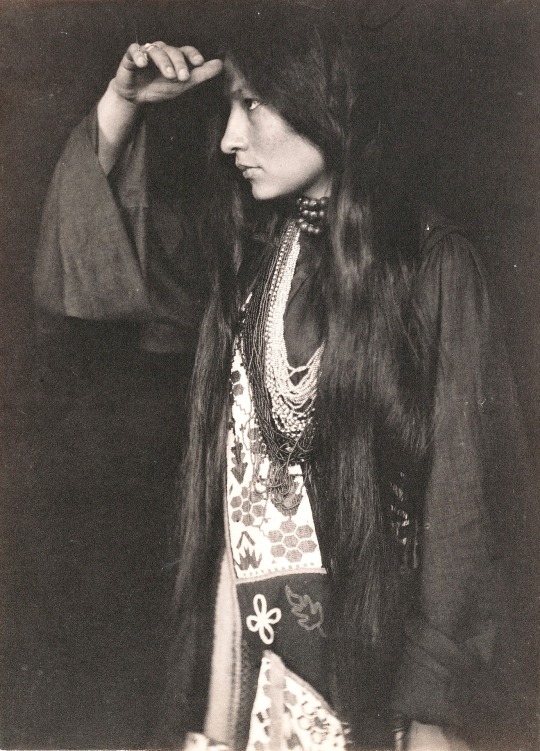

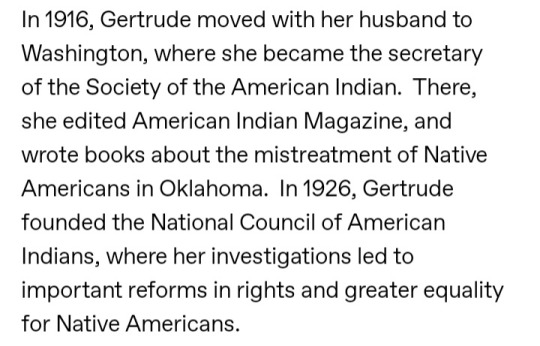

Gertrude Käsebier :: Zitkala Sa, Sioux Indian and activist, ca. 1898 | src NMAH

view more Zitkala-sa by Käsebier on wordPress

#gertrude kasebier#zitkala sa#sioux#native american#pictorial portrait#pictorialist portrait#pictorialism#photosecession#gertrude käsebier#portrait#women artists#women photographers#beauty#gertrude simmons#red bird

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Gertrude Käsebier - Zitkala Sa, Sioux Indian, ca. 1898

171 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gertrude Kasebier, Zitkala Sa, aka Red Bird, 1892. Red Bird was a writer, editor, musician, teacher, and political activist of Native American Yankton Sioux heritage.

15 notes

·

View notes

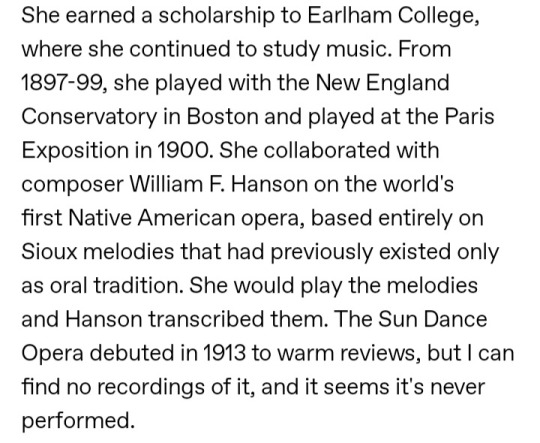

Photo

#Zitkála-Šá#Gertrude Simmons Bonnin#Zitkala-Sa#Yankton Dakota#indigenous#activist#political activist#women's right activist#writer#educator#musician#gertrude#native#zitkala sa#suffragette#squaw

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

#zitkala sa#zitkala-sa#sioux#sioux indian#natives#american indians#indigenous people#opera#sun dance#brigham young university#reform#american opera#boston conservatory of music#politics#the atlantic monthly#harper's magazine#oklahoma#pennsylvania#carlisle indian industrial school#euro american#sioux melodies#gertrude bonnin#indigenous#history#american history

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Red Man's America

My country! 'tis to thee,

Sweet land of Liberty,

My pleas I bring.

Land where OUR fathers died,

Whose offspring are denied

The Franchise given wide,

Hark, while I sing.

My native country, thee,

Thy Red man is not free,

Knows not thy love.

Political bred ills,

Peyote in temple hills,

His heart with sorrow fills,

Knows not thy love.

Let Lane's Bill swell the breeze,

And ring from all the trees,

Sweet freedom's song.

Let Gandy's Bill awake

All people, till they quake,

Let Congress, silence break,

The sound prolong.

Great Mystery, to thee,

Life of humanity,

To thee, we cling.

Grant our home land be bright,

Grant us just human right,

Protect us by Thy might,

Great God, our king.

— Zitkála-Šá (Gertrude Simmons Bonnin), (1876–1938)

When the Light of the World Was Subdued, Our Songs Came Through: A Norton Anthology of Native Nations Poetry (2020)

#The Red Man's America#Zitkala Sa#Zitkala-Sa#Gertrude Simmons Bonnin#poetry#poem#poems#Native American#When the Light of the World Was Subdued Our Songs Came Through

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

currently reading

#zitkala sa#summer reading#books#stories#poems#sun dance opera#dreams and thunder#indigenous#sioux#book cover#reading

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

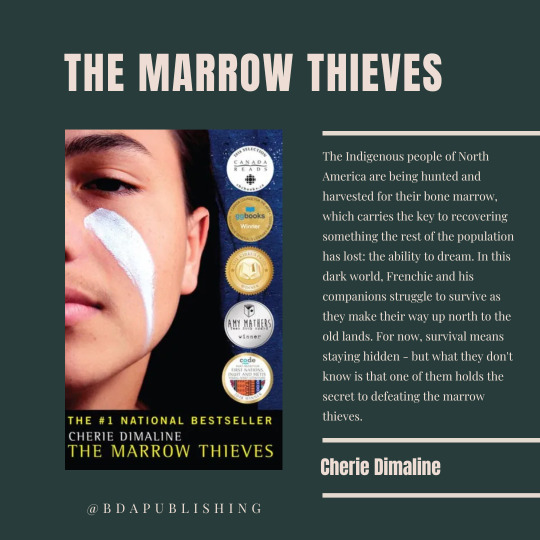

zitkala-sa or red bird (1876-1938) was was a yankton dakota writer, editor, translator, musician, educator, and political activist. her later books were among the first works to bring traditional native american stories to a widespread white english-speaking readership. she was co-founder of the national coouncil of american indians in 1926, which was established to lobby for native people's right to united states citizenship and other civil rights they had long been denied. when she was a child, she was taken to white's indiana manual labor Institute, a quaker missionary boarding school in wabash, indiana. this training school was founded by josiah white for the education of "poor children, white, colored, and indian to help them advance in society.” she wrote about this in one of her books describing the misery of having her hertiage stripped from her and being forced to cut her hair.

#women's history month#history#women in history#women's history#zitkala-sa#red bird#native american history

295 notes

·

View notes

Text

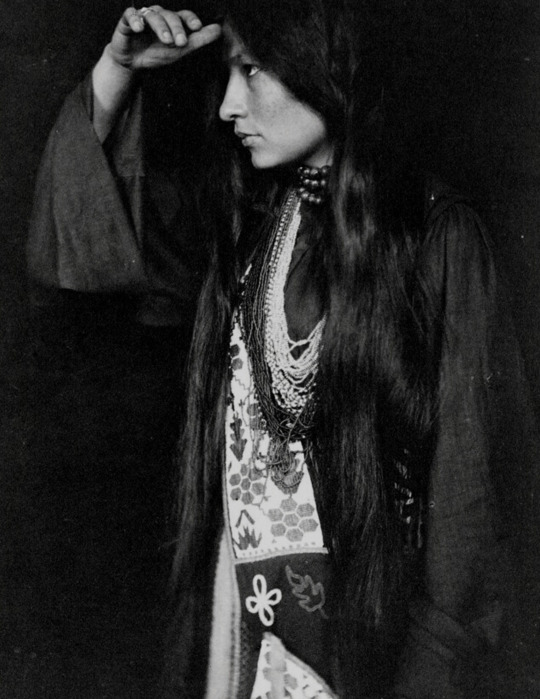

In the 19th and 20th centuries, the U.S. established federally funded Indian Boarding Schools that aimed to strip Native American Children of their culture. The Carlisle Indian Industrial School, pictured here, was the most prominent. Photograph Via Library of Congress

A Century of Trauma at U.S. Boarding Schools For Native American Children

Federally Funded Schools used abusive tactics to strip children of their culture and inspired a similar program in Canada. A new initiative aims to reckon with that past.

— By Erin Blakemore | July 9, 2021 | National Geographic

Zitkála-Šá was eight years old when the missionaries came. Lured from the South Dakota Yankton Indian Reservation with promises of adventure, comfort, and an education, in 1884 the girl went willingly to Wabash, Indiana, to attend a Quaker-run boarding school dedicated to training Native American children.

Then she realized the teachers who had taken her traditional clothing upon her arrival wanted to cut her hair, too. Proud of her long black hair and raised to associate short cuts with the shame of captured warriors, Zitkála-Šá snuck away from the other children. But the adults found her hiding place. They dragged the kicking child into another room and tied her to a chair.

Zitkala-Sa, Native American Author and Activist: In adulthood, Zitkála-Šá grew her hair long in defiance of the boarding school that had forced her to cut it to assimilate into white culture. As a writer and activist, she spent her life fighting for Native American rights. Photograph Via Science History Images/Alamy

“I cried aloud, shaking my head all the while until I felt the cold blades of the scissors against my neck, and heard them gnaw off one of my thick braids,” she wrote in her 1921 memoir American Indian Stories. “Then I lost my spirit.” Renamed Gertrude by the missionaries, Zitkála-Šá would go on to live most of the rest of her childhood at boarding schools for Native students. (Zitkála-Šá went on to fight for suffrage for women and Native Americans.)

She was one of hundreds of thousands of students who attended such schools in the United States in the 19th and 20th centuries. The U.S. boarding schools inspired a similar program in Canada, which is now reeling from the discovery of hundreds of unmarked graves at the residential schools its First Nations children were forced to attend.

The grisly discovery has also forced a reckoning in the U.S. about its residential boarding schools which punished Native students for speaking their languages, forced them to take new names, and coerced them to convert to Christianity. And many were federally funded in an ambitious attempt to force Native Americans to assimilate into white American society.

The First Native American Boarding School

Native Americans had inhabited and tended their traditional lands for thousands of years before the arrival of white settlers in the 1600s. Rather than learn from the land’s indigenous people, however, the settlers began to pressure Native Americans to abandon their traditional societies and adopt the ways of the new republic.

In 1830, Congress passed the Indian Removal Act, a law that allowed the federal government to exchange land in the western U.S. for some tribes’ ancestral homelands in the east. But despite brokering more than 350 treaties with Native tribes, the U.S. did not fulfill its promises. Instead of allowing Native people to establish permanent homes in the west, it pushed them onto government-assigned reservations.

The U.S. Boarding Schools For Native American Children

Opened in 1879, the Carlisle Indian Industrial School was the first boarding school to educate Native American children in an off-reservation setting, far from home. The federally funded school's philosophy was to "kill the Indian, save the man," forcing their assimilation to white culture by forbidding the use of native languages and cultural practices. In 1891, the U.S. passed a law making attendance compulsory for Indigenous children. The Carlisle school became the blueprint for over 300 such schools across the United States.

Rosemary Wardley, NG Staff. Mike Boruta. Source: National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition (NABS)

At first, education was in the hands of missionaries, some of whom set up schools on and near the new reservations. But as white settlers flooded into the western U.S. in the mid 19th century, forced assimilation became a federal priority. The government started to invest in mission schools and day schools. But over time, writes historian Ronald C. Naugle, “The reservation environment, to which the child returned daily, undermined the process of assimilation.”

Over its nearly 30 years in operation, more than 12,000 Native American children attended the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. The school's philosophy was to "kill the Indian" in its students and instead instill them with white settlers' cultural values. Photograph Via Library of Congress

Instead, the U.S. turned to the idea of off-reservation boarding schools. It found a blueprint in the work of Army General Richard Henry Pratt, who oversaw the education of a group of Native American prisoners of war in Fort Marion, Florida. Pratt’s philosophy was what he called “kill the Indian, and save the man.” He was convinced that if Native children were removed from their Native context and placed in an Anglo one, they would assimilate within a generation.

Pratt convinced the federal government to invest in a pricey experiment: a boarding school in Pennsylvania that educated Native children far from home. The Carlisle Indian Industrial School, which Pratt opened in 1879, would become the most prominent of the 25 federally funded off-reservation boarding schools that would open over the next few decades. (More than 300 other day and on-reservation boarding schools received federal funding as well.)

The Carlisle Indian Industrial School was upheld as a model throughout the nation. Its influence didn’t end there: In 1879, the Canadian government sent lawyer Nicholas Flood Davin to the U.S. on a fact-finding mission. Davin visited the Carlisle school and other institutions and returned to Canada with a glowing review of the new educational system. Davin recommended the government create its own residential school system as soon as possible.

Abuse in the Name of Assimilation

At the federal boarding schools, which were located in white communities, children were given Anglo names. Their native languages and cultural practices were forbidden. Their strict educations included language lessons and studies in subjects like manual labor, housekeeping, and farming, and students were usually required to help keep the school self-sufficient by laboring there when they were not in the classroom.

For many, the schools were hotbeds of humiliation, abuse, and victimization. They were also dangerous. Unsanitary conditions and overcrowding fueled communicable diseases such as tuberculosis, influenza, and smallpox, especially among students weakened by trauma and meager rations. Schools had their own cemeteries—and students often built their classmates’ coffins.

Other children died by suicide or ran away. The practice was so common that some schools offered bounties for runaways. “The temptation to return to their wild life, with the savage influences surrounding them, is no doubt very strong,” wrote one newspaper reporter in a lengthy article about life at White’s Indiana Manual Labor Institute in Wabash, Indiana, the school Zitkála-Šá attended.

Yet the U.S. government considered the schools a success—so much so that in 1891, it passed a federal law that made attendance compulsory for Native children. The Bureau of Indian Affairs—the federal agency tasked with distributing food, land, and other provisions included in treaties with Native tribes—withheld food and other goods from those who refused to send their children to the schools, and even sent officers to forcibly take children from the reservation. It was “civilization by kidnapping,” said one Native American advocate at a 1927 Congressional hearing.

Earlier generations of Native Americans had suffered the loss of nearly all of their lands. Now, the boarding schools broke up their family units and endangered their languages and cultural practices.

But many Native parents did not part from their children without a fight. One memorable act of protest occurred in 1894, when a group of Hopi men in Arizona refused to send their children to residential schools. Nineteen of them were taken to Alcatraz Island in California, about a thousand miles away from their families, and imprisoned for a year.

The Fight to Close the Boarding Schools

At the beginning of the 20th century, however, enthusiasm for the system dwindled and the schools floundered. In 1928, the U.S. government commissioned what is now known as the Meriam Report, a comprehensive update on the state of Native American affairs. Its authors criticized everything from the schools’ deteriorating conditions to the often heavy manual labor the children were forced to perform, and pointed out that the schools relied on long outdated teaching techniques like rote learning and recitation. Students were stiff, hungry, sick, and demoralized, they wrote, and were subjected to harsh physical punishments.

The report resulted in some immediate changes—among them, the emergency allocation of funds for better food and clothing in the schools. But even though the report recommended dismantling the boarding school system in favor of day schools, the schools persisted.

Meanwhile, the fractures they had introduced into Native culture widened. Native languages began to die out, fueled by children’s absence from the reservation and their forced use of English. Traditional parenting skills were not passed on to younger generations. And over the years, children at the schools reported widespread neglect and physical and sexual abuse.

“The most debilitating message was one of self-hatred,” writes Mending the Sacred Hoop, a Native-owned nonprofit that works to end violence against Native women. In a 2003 report on the boarding school experience, the nonprofit traced violence in Native American communities—which experience an order of magnitude more violence than their majority white counterparts—to the abuse and trauma many children suffered during their educations.

Native Americans continued to fight to close down the schools. Self-determined education was a priority for the burgeoning pan-Indian movement in the 1960s and 1970s. In 1975, Congress passed the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act, which granted tribes the ability to assume responsibility for programs that had been administered by the federal government. (The radical history of the Red Power movement’s fight for Native American sovereignty.)

It was the death knell for most residential schools, but a few remain. Today, the U.S. Bureau of Indian Education still directly operates four off-reservation boarding schools in Oklahoma, California, Oregon, and South Dakota. According to the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition (NABS), a Native-run nonprofit, 15 boarding schools and 73 total schools with federal funding remain open as of 2021.

Reckoning With The Past

In the late 20th century, the federal government began to acknowledge the schools’ grisly legacy. In 2009, Congress passed a joint resolution of apology to Native Americans that included a reference to “the forcible removal of Native children from their families to faraway boarding schools where their Native practices and languages were degraded and forbidden.” In 2016, the U.S. Army began repatriating the remains of some of the bodies buried at the Carlisle Indian School to their tribes and bands. It is the only known effort to do so in the United States; repatriation is ongoing.

The number of children who were sent to off-reservation residential boarding schools over their century-long history is unclear. But the scars remain—and intergenerational wounds were reopened with recent reports of the unmarked graves in Canada. In response, Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland, the first Native American to serve as a cabinet secretary, announced the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative, a program designed to review the schools’ histories and legacy. The program will investigate known and suspected burial sites.

The Native American boarding school coalition applauded the initiative. “We have a right to know what happened to the children who never returned home from Indian boarding schools,” the NABS said in a release. “The time is now for truth and healing.”

#Boarding School Trauma#Native American Children#United States 🇺🇸 Boarding Schools 🏫#Federally Funded Schools#Zitkala-Sa | Native American 🇺🇸 Author | Activist

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Twelve Famous Native American Women

Native American women are traditionally held in high regard among the diverse nations, whether a given people are matrilineal or patrilineal. Traditionally, women were not only responsible for raising children and caring for the home but also planted and harvested the crops, built the homes, and engaged in trade, as well as having a voice in government.

The history of the women of the Native peoples of North America attests to their full participation in the community whether as elders and "medicine women" or as skilled agriculturalists and merchants and, in some cases, even warriors. Although hunting and warfare were traditionally the provenance of males, some women became famous for their courage and skill in battle. These women, as well as others in the arts and sciences, are often overlooked because they do not fit the paradigm of what has been accepted as American history.

Pocahontas and Sacagawea are usually the only North American Native women that non-Natives have heard of, but even their narratives have been obscured by legend and half-truths. Many other Native American women have simply been ignored, and among them are most of those listed below. These women, and the nations they were citizens of, include:

Jigonhsasee – Iroquois

Pocahontas – Powhattan

Weetamoo – Wampanoag

Glory-of-the-Morning – Ho-Chunk/Winnebago

Sacagawea – Shoshone

Old-Lady-Grieves-the-Enemy – Pawnee

Pine Leaf/Woman Chief – Crow

Lozen – Apache

Buffalo Calf Road Woman – Cheyenne

Thocmentony/Sarah Winnemucca – Paiute

Susan La Flesche Picotte – Omaha

Molly Spotted Elk/Mary Alice Nelson – Penobscot

There are many others who do not appear here because they are more widely known, such as the Yankton Dakota activist, musician, and writer, Zitkala-Sa (l. 1876-1938) or the Cheyenne warrior Mochi ("Buffalo Calf", l. c. 1841-1881). Modern-day figures are also omitted but deserve mention, such as the activist Isabella Aiukli Cornell of the Choctaw nation, who drew national attention in 2018 with her red prom dress designed to call attention to the many missing and murdered indigenous women across North America, and poet/activist Suzan Shown Harjo of the Muscogee/Southern Cheyenne nation. There are many more, like these two, who have devoted themselves to raising awareness of the challenges facing Native Americans and continue the same struggle, in various ways, as the women of the past.

Jigonhsasee (l. c. 1142 or 15th century)

According to Iroquois lore, Jigonhsasee (Jikonhsaseh, Jikonsase) was integral to the origins of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy dated to either the 12th or 15th century. She was an Iroquoian whose home was along the central path used by warriors going to and from battle and became well-known for the hospitality and wise counsel she offered them. The Great Peacemaker (Deganawida) chose her to help him form the Iroquois Confederacy, based on the model of a family living together in one longhouse, and, along with Hiawatha, this vision became a reality. Jigonhsasee became known as the 'Mother of Nations' and established the policy of women choosing the chiefs of the council in the interests of peace, instead of war. The American women's suffrage movement of the 19th century called attention to the freedom and rights of Native American women, notably those of the Iroquois Confederacy, in arguing for those same rights for themselves.

Continue reading...

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

Joseph T. Keiley :: Zit-Kala-Za, ca. 1898. Platinum print with glycerine development. | Philadelphia museum of Art

Joseph Turner Keiley :: Zitkála-Šá (1876-1938), 1898. Glycerine-developed platinum print. | src NPG ~ Smithsonian Institution

view & read more on wordPress

#zitkala sa#zit-kala-sa#native american#sioux#portrait#american pictorialism#pictorialism#pictorialist portrait#1890s#platinum print#activist#red bird#gertrude simmons

142 notes

·

View notes

Text

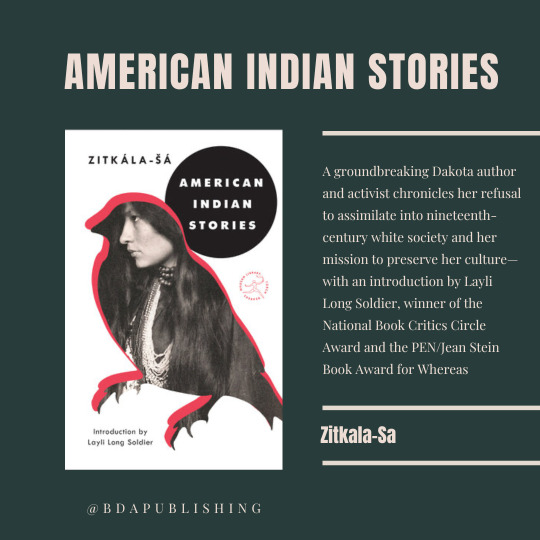

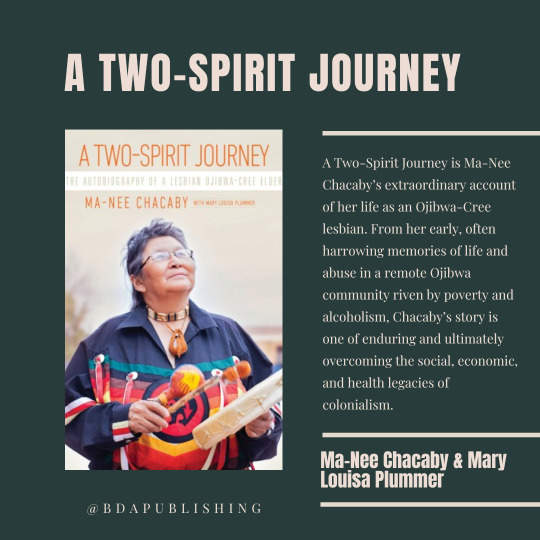

Happy Friday, Bookblr! This holiday weekend, the BDA team is honoring and amplifying Indigenous voices by showcasing four incredible authors and their powerful stories. Join us in celebrating the richness of Indigenous literature with Cherie Dimaline's "The Marrow Thieves," Ma-Nee Chacaby & Mary Louisa Plummer's "A Two-Spirit Journey," and Zitkala-Sa's "American Indian Stories." Let's carve out space for diverse narratives and gratitude for the wisdom these authors share.

#bookblr#booklover#books#books and reading#reading#bookworm#books and literature#book blog#indigenous authors#book recs#book recommendations#book cover

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

I keep forgetting about tumblr ngl! haha but anyway another dnd character of mine! Zitkala-sa a hombrewed race called a Fethros for a homebrewed world. She's a paladin based off a Harpy eagle. Poor girl has big heart, big musle but no brain. All the dummy so she can have maximum thic

#digital art#artists on tumblr#art#dnd character#dnd#original character#dnd art#paladin#big tiddy committee#big dumb

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#zitkala-sa#indigenous#activist#Zitkála-Šá#Yankton Dakota#Gertrude Simmons Bonnin#political activist#women's right activist#writer#suffragette#squaw

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

I was a wild little girl of seven. Loosely clad in a slip of brown buckskin, and light-footed with a pair of soft moccasins on my feet, I was as free as the wind that blew my hair, and no less spirited than a bounding deer.

-Zitkala-Sa

1 note

·

View note

Photo

A portrait of musician/composer Zitkala Sa, “Red Bird,” also known as Gertrude Simmons by photographer Joseph T. Keiley, 1898.

143 notes

·

View notes