Text

"Verse was invented as an aid to memory. Later it was preserved to increase pleasure by the spectacle of difficulty overcome. That it should still survive in dramatic art is a vestige of barbarism."

--Stendhal, "de l'Amour," 1822

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bob Cluness -An Esoteric Menagerie: The Weird & Eerie, Slenderman, CCRU, Accelerationism, Chaos Magic(k) and Digital Technology

Part 1

Part 2

#anti platonism#antiplatonism#marx and mysticism#the digital age#digital#karl marx#postmodernism#mark fisher#ccru#hyperstition#western esotericism#western esoteric tradition#podcast#rejected religion#chaos magick#magic#the internet#Frenchphilosophers#Accelerationism#Cybernetics#Hyperstition#Technology#Ccru#Slenderman#Neoliberalism#Chaosmagick#Culturalhistory#Fiction#New Age#Cyberpunk

0 notes

Text

Hartmann, Eduard von (1842–1906) from The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy

German philosopher who sought to synthesize the thought of Schelling, Hegel, and Schopenhauer. The most important of his fifteen books was Philosophie des Unbewussten (Philosophy of the Unconscious, 1869). For Hartmann both will and idea are interrelated and are expressions of an absolute “thing-in-itself,” the unconscious. The unconscious is the active essence in natural and psychic processes and is the teleological dynamic in organic life. Paradoxically, he claimed that the teleology immanent in the world order and the life process leads to insight into the irrationality of the “will-to-live.” The maturation of rational consciousness would, he held, lead to the negation of the total volitional process and the entire world process would cease. Ideas indicate the “what” of existence and constitute, along with will and the unconscious, the three modes of being. Despite its pessimism, this work enjoyed considerable popularity.

Hartmann was an unusual combination of speculative idealist and philosopher of science (defending vitalism and attacking mechanistic materialism); his pessimistic ethics was part of a cosmic drama of redemption. Some of his later works dealt with a critical form of Darwinism that led him to adopt a positive evolutionary stance that undermined his earlier pessimism. His general philosophical position was selfdescribed as “transcendental realism.” His Philosophy of the Unconscious was translated into English by W. C. Coupland in three volumes in 1884. There is little doubt that his metaphysics of the unconscious prepared the way for Freud’s later theory of the unconscious mind.

See Also:

The Physiological Unconscious

#darwinian unconscious#unconscious#linguistic unconscious#critical theory#the critical tradition#Physiological Unconscious#Philosophy of the Unconscious#German idealism#german romanticism#romanticism#romantic philosophy#will#schopenauer#philosophy of the unconscious#teleology#teleodynamics#mind#Schelling#hegel#georg wilhelm friedrich hegel#darwin as master of suspicion#darwinian unconcious#transcendental realism#Eduard von Hartmann#philosophy#philosophy of science#philosophy of mind#Sigmund Freud#freud#freudian

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Karin Valis on Magic and Artificial Intelligence – The Secret History of Western Esotericism Podcast (SHWEP)

A House with Many Rooms Interview 2

We are delighted to speak with Karin Valis, machine-learning engineer and esoteric explorer, on the vast subject of how the fields of artificial intelligence and magic overlap, intertwine, and inform each other. We discuss:

The uncanny oracular effects and synchronistic weirdnesses exhibited by large language models,

Conversations with ChatGPT considered as invocation,

AI as the fulfilment of the dream of the homonculus (with the attendant ethical problems which arise),

AI as the fulfilment of esoteric alphanumeric cosmologies (and maybe, like the Sepher Yetsirah, this isn’t so esoteric after all; maybe it’s just science),

And much more.

Interview Bio:

Karin Valis is a Berlin-based machine learning engineer and writer with a deep passion for everything occult and weird. Her work focuses mainly on combining technology with the esoteric, with projects such as Tarot of the Latent Spaces (visual extraction of the Major Arcana Archetypes) and Cellulare (a tool for exploring digital non-ordinary reality for the Foundation for Shamanic Studies Europe). She co-hosted workshops, talks and panel discussions such as Arana in the Feed (Uroboros 2021), Language in the Age of AI: Deciphering Voynich Manuscript (Trans-States 2022) and Remembering Our Future: Shamanism, Oracles and AI (NYU Shanghai 2022). She writes Mercurial Minutes and hosts monthly meetings of the occult and technology enthusiasts Gnostic Technology.

Works Cited in this Episode (roughly in the order cited):

The homonculus passage in the Pseudo-Clementines: Homilies 3.26; cf. Recognitions 2.9, 10, 13–15; 3.47.

On the Book of the Cow/Liber vaccæ: see e.g. Liana Saif. The Cows and the Bees: Arabic Sources and Parallels for Pseudo- Plato’s Liber Vaccæ (Kitab al-Nawams). Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, LXXIX:147, 2016.

‘The Measure of a Man’, Star Trek: The Next Generation Season 2, Episode 9, first aired 13 February, 1989.

Doctor Strange, dir. Scott Derrickson, 2016 Marvel Studios.

Recommended Reading:

Karin has a substack where she posts interesting things. Her recent essay Divine Embeddings is particularly relevant to the discussion of alphanumericism in the interview.

#history of science#ai#artificial intelligence#ai art#philosophy of science#history#media theory#magic#history of mathematics#history of computing#history of religion#the digital age#alchemy#kabbalism#golem#homunculi#homuncus fallacy#western esoteric tradition#marx and computing#marx and mysticism#the digital#shwep#the critical tradition

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"History is not a science, it is Literature that answers to certain scientific standards." -Tzi Langermann

0 notes

Text

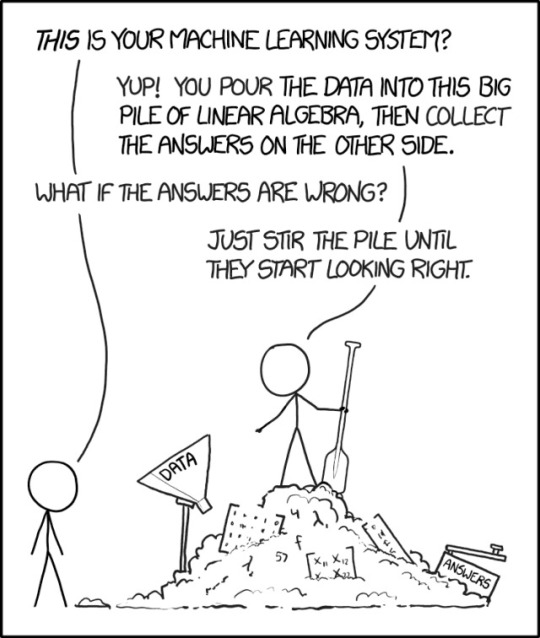

#history of computing#ai#artificial intelligence#machine learning#xkcd#media theory#mathematics#computers#computing

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

“If you look carefully at life, you see blur. Shake your hand. Blur is a part of life.”

— William Klein

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

It may take generations of effort but it is possible, and honorable, to move the Earth

Stories of humans leaving Earth behind due to catastrophe are not rare, but the mass exodus usually happens on a spaceship. I'm going to make a bold generalization here but I think a lot of you would agree these movies draw their philosophy from Noah's ark. In the west, when nature is destroyed it's usually unstoppable, like the wrath of god. Humans live in god's creation, so when god's creation comes to an end, humanity is at god's mercy. In Chinese mythology however, there is no such supreme being, humans and gods alike obey the natural order, the "Tao", if you will.

So, in Chinese flood myths the hole in the sky is patched up by a goddess, the flood from the Yellow River was contained and drained by human constructions over the course of 13 long years. The Chinese equivalent of the Icarus myth talks about a man chasing the sun and dying of thirst, but he leaves behind a peach forest as a water supply so that future generations may continue the chase. In Chinese mythology, and thus, philosophy, nature is malleable: It can be shaped, it can be conquered. It may take generations of effort but it is possible, and honorable, to move the Earth.

-- Accented Cinema, The Wandering Earth: How to Tell a Chinese Story

#chinese philosophy#taoism#Daoism#tao#hermeticism#philosophy#Film Theory#film#film criticism#creation#immanentism#nature#incomplete nature#Karl Marx and Human Self Creation#marx and mysticism#God#divinity in nature#hermetic philosophy#the wandering earth#mythology#accented cinema#chinese mythology

33 notes

·

View notes

Link

According to Hertog, the new perspective that he has achieved with Hawking reverses the hierarchy between laws and reality in physics and is “profoundly Darwinian” in spirit. “It leads to a new philosophy of physics that rejects the idea that the universe is a machine governed by unconditional laws with a prior existence, and replaces it with a view of the universe as a kind of self-organising entity in which all sorts of emergent patterns appear, the most general of which we call the laws of physics.”

#stephen hawking#physics#philosophy of science#hawking#emergence#Emergence theory#self organization#Terrence Deacon#Deacon#darwin#Charles Darwin#Great Chain of Being#Panpsychism#anti-platonism

0 notes

Text

Emotion and Energy

An excerpt from Incomplete Nature by Terrence W. Deacon

Emergent dynamics: A theory developed in this book which explains how homeodynamic (e.g., thermodynamic) processes can give rise to morphodynamic (e.g., self-organizing) processes, which can give rise to teleodynamic (e.g., living and mental) processes. Intended to legitimize scientific uses of ententional (intentional, purposeful, normative) concepts by demonstrating the way that processes at a higher level in this hierarchy emerge from, and are grounded in, simpler physical processes, but exhibit reversals of the otherwise ubiquitous tendencies of these lower-level processes

Emotion and Energy

An emergent dynamic account of the relationship between neurological function and mental experience differs from all other approaches by virtue of its necessary requirement for specifying a homeodynamic and morphodynamic basis for its teleodynamic (intentional) character. This means that every mental process will inevitably reflect the contributions of these necessary lower-level dynamics. In other words, certain ubiquitous aspects of mental experience should inevitably exhibit organizational features that derive from, and assume certain dynamical properties characteristic of, thermodynamic and morphodynamic processes. To state this more concretely: experience should have clear equilibrium-tending, dissipative, and self-organizing characteristics, besides those that are intentional. These are inseparable dynamical features that literally constitute experience. What do these dynamical features correspond to in our phenomenal experience?

Broadly speaking, this dynamical infrastructure is “emotion” in the most general sense of that word. It is what constitutes the “what it feels like” of subjective experience. Emotion—in the broad sense that I am using it here—is not merely confined to such highly excited states as fear, rage, sexual arousal, love, craving, and so forth. It is present in every experience, even if often highly attenuated, because it is the expression of the necessary dynamic infrastructure of all mental activity. It is the tension that separates self from non-self; the way things are and the way they could be; the very embodiment of the intrinsic incompleteness of subjective experience that constitutes its perpetual becoming. It is a tension that inevitably arises as the incessant shifting course of mental teleodynamics encounters the resistance of the body to respond, and the insistence of bodily needs and drives to derail thought, as well as the resistance of the world to conform to expectation. As a result, it is the mark that distinguishes subjective self from other, and is at the same time the spontaneous tendency to minimize this disequilibrium and difference. In simple terms, it is the mental tension that is created because of the presence of a kind of inertia and momentum associated with the process of generating and modifying mental representations. The term e-motion is in this respect curiously appropriate to the “dynamical feel” of mental experience.

This almost Newtonian nature of emotion is reflected in the way that the metaphors of folk psychology have described this aspect of human subjectivity over the course of history in many different societies. Thus English speakers are “moved” to tears, “driven” to behave in ways we regret, “swept up” by the mood of the crowd, angered to the point that we feel ready to “explode,” “under pressure” to perform, “blocked” by our inability to remember, and so forth. And we often let our “pent-up” frustrations “leak out” into our casual conversations, despite our best efforts to “contain” them. Both the motive and resistive aspects of experience are thus commonly expressed in energetic terms.

In the Yogic traditions of India and Tibet, the term kundalini refers to a source of living and spiritual motive force. It is figuratively “coiled” in the base of the spine, like a serpent poised to strike or a spring compressed and ready to expand. In this process, it animates body and spirit. The subjective experience of bodily states has also often been attributed to physical or ephemeral forms of fluid dynamics. In ancient Chinese medicine, this fluid is chi; in the Ayurvedic medicine of India, there were three fluids, the doshas; and in Greek, Roman, and later Islamic medicine, there were four humors (blood, phlegm, light and dark bile) responsible for one’s state of mental and physical health. In all of these traditions, the balance, pressures, and free movement of these fluids were critical to the animation of the body, and their proper balance was presumed to be important to good health and “good humor.” The humor theory of Hippocrates, for example, led to a variety of medical practices designed to rebalance the humors that were disturbed by disease or disruptive mental experience. Thus bloodletting was deemed an important way to adjust relative levels of these humors to treat disease.

This fluid dynamical conception of mental and physical animation was naturally reinforced by the ubiquitous correlation of a pounding heart (a pump) with intense emotion, stress, and intense exertion. Both René Descartes and Erasmus Darwin (to mention only two among many) argued that the nervous system likewise animates the body by virtue of differentially pumping fluid into various muscles and organs through microscopic tubes (presumably the nerves). When, in the 1780s, Luigi Galvani discovered that a severed frog leg could be induced to twitch in response to contact by electricity, he considered this energy to be an “animal electricity.” And the vitalist notion of a special ineffable fluid of life, or élan vital, persisted even into the twentieth century.

This way of conceiving of the emotions did not disappear with the replacement of vitalism and with the rise of anatomical and physiological knowledge in the nineteenth and early twentieth century. It was famously reincarnated in Freudian psychology as the theory of libido. Though Freud was careful not to identify it with an actual fluid of the body, or even a yet-to-be-discovered material substrate, libido was described in terms that implied that it was something like the nervous energy associated with sexuality. Thus a repressed memory might block the “flow” of libido and cause its flow to be displaced, accumulated, and released to animate inappropriate behaviors. Freud’s usage of this hydrodynamic metaphor became interpreted more concretely in the Freudian-inspired theories of Wilhelm Reich, who argued that there was literally a special form of energy, which he called “orgone” energy, that constituted the libido. Although such notions have long been abandoned and discredited with the rise of the neurosciences, there is still a sense in which the pharmacological treatments for mental illness are sometimes conceived of on the analogy of a balance of fluids: that is, neurotransmitter “levels.” Thus different forms of mental illness are sometimes described in terms of the relative levels of dopamine, norepinephrine, or serotonin that can be manipulated by drugs that alter their production or interfere with their effects.

This folk psychology of emotion was challenged in the 1960s and 1970s by a group of prominent theorists, responsible for ushering in the information age. Among them was Gregory Bateson, who argued that the use of these energetic analogies and metaphors in psychology made a critical error in treating information processes as energetic processes. He argued that the appropriate way to conceive of mental processes was in informational and cybernetic terms. Brains are not pumps, and although axons are indeed tubular, and molecules such as neurotransmitters are actively conveyed along their length, they do not contribute to a hydrodynamic process. Nervous signals are propagated ionic potentials, mediated by molecular signals linking cells across tiny synaptic gaps. On the model of a cybernetic control system, he argued that the differences conveyed by neurological signals are organized so that they regulate the release of “collateral energy,” generated by metabolism. It is this independently available energy that is responsible for animating the body. Nervous control of this was thus more accurately modeled cybernetically. This collateral metabolic energy is analogous to the energy generated in a furnace, whose level of energy release is regulated by the much weaker changes in energy of the electrical signals propagated around the control circuit of a thermostat. According to Bateson, the mental world is not constituted by energy and matter, but rather by information. And as was also pioneered by the architects of the cybernetic theory whom Bateson drew his insights from, such as Wiener and Ashby, and biologists such as Warren McCulloch and Mayr, information was conceived of in purely logical terms: in other words, Shannon information. Implicit in this view—which gave rise to the computational perspective in the decades that followed—the folk wisdom expressed in energetic metaphors was deemed to be misleading.

By more precisely articulating the ways that thermodynamic, morphodynamic, and teleodynamic processes emerge from, and depend on, one another, however, we have seen that it is this overly simple energy/information dichotomy that is misleading. Information cannot so easily be disentangled from its basis in the capacity to reflect the effects of work (and thus the exchange of energy), and neither can it be simply reduced to it. Energy and information are asymmetrically and hierarchically interdependent dynamical concepts, which are linked by virtue of an intervening level of morphodynamic processes. And by virtue of this dynamical ascent, the capacity to be about something not present also emerges; not as mere signal difference, but as something extrinsic and absent yet potentially relevant to the existence of the teleodynamic (interpretive) processes thereby produced.

It is indeed the case that mental experience cannot be identified with the ebb and flow of some vital fluid, nor can it be identified directly with the buildup and release of energy. But as we’ve now also discovered by critically deconstructing the computer analogy, it cannot be identified with the signal patterns conveyed from neuron to neuron, either. These signals are generated and analyzed with respect to the teleodynamics of neuronal cell maintenance. They are interpreted with respect to cellular-level sentience. Each neuron is bombarded with signals that constitute its Umwelt. They perturb its metabolic state and force it to adapt in order to reestablish its stable teleodynamic “resting” activity. But, as was noted in the previous chapter, the structure of these neuronal signals does not constitute mental information, any more than the collisions between gas molecules constitute the attractor logic of the second law of thermodynamics.

As we will explore more fully below, mental information is constituted at a higher population dynamic level of signal regularity. As opposed to neuronal information (which can superficially be analyzed in computational terms), mental information is embodied by distributed dynamical attractors. These higher-order, more global dynamical regularities are constituted by the incessantly recirculating and restimulating neural signals within vast networks of interconnected neurons. The attractors form as these recirculating signals damp some and amplify other intrinsic constraints implicit in the current network geometry. Looking for mental information in individual neuronal firing patterns is looking at the wrong level of scale and at the wrong kind of physical manifestation. As in other statistical dynamical regularities, there are a vast number of microstates (i.e., network activity patterns) that can constitute the same global attractor, and a vast number of trajectories of microstate-to-microstate changes that will tend to converge to a common attractor. But it is the final quasi-regular network-level dynamic, like a melody played by a million-instrument orchestra, that is the medium of mental information. Although the contribution of each neuronal response is important, it is more with respect to how this contributes a local micro bias to the larger dynamic. To repeat again, it is no more a determinate of mental content than the collision between two atoms in a gas determines the tendency of the gas to develop toward equilibrium (though the fact that neurons are teleodynamic components rather than simply mechanical components makes this analogy far too simple).

This shift in level makes it less clear that we can simply dismiss these folk psychology force-motion analogies. If the medium of mental representation is not mere signal difference, but instead is the large-scale global attractor dynamic produced by an extended interconnected population of neurons, then there may also be global-level homeodynamic properties to be taken into account as well. As we have seen in earlier chapters, these global dynamical regularities will exhibit many features that are also characteristic of force-motion dynamics.

#Terrence Deacon#Deacon#incomplete nature#Emergence theory#Emergentism#emergence#teleodynamics#homeodynamics#morphodynamics#mental#consciousness#intentionally#analogy#pneuma#soma pneumatikon#theory of mind#Neuroscience#neurology#neurobiology#neurones#marx and mysticism#emotion#energy#newton#yoga#hinduism#vedic philosophy#kundalini#spirit#spirituality

1 note

·

View note

Text

Part of everybody's brain is missing, because that’s how brains work.

0 notes

Quote

What is energy? One might expect at this point a nice clear, concise definition. Pick up a chemistry text, a physics text, or a thermodynamics text, and look in the index for “Energy, definition of,” and you find no such entry. You think this may be an oversight; so you turn to the appropriate sections of these books, study them, and find no help at all. Every time they have an opportunity to define energy, they fail to do so. Why the big secret? Or is it presumed you already know? Or is it just obvious?

H. C. Van Ness, Understanding Thermodynamics (1969)

#energy#thermodynamics#van ness#Terrence Deacon#Deacon#philosophy of science#Understanding Thermodynamics#history of science

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lionel Giles on Christianity, Taoism and Hegel

A foreigner, imbued with Christian ideas, naturally feels inclined to substitute for Tao the term by which he is accustomed to denote the Supreme Being--God. But this is only admissible if he is prepared to use the term 'God' in a much broader sense than we find in either the Old or the New Testament. That which chiefly impresses the Taoist in the operations of Nature is their absolute impersonality. The inexorable law of cause and effect seems to him equally removed from active goodness or benevolence on the one hand, and from active, or malevolence on the other. This is a fact which will hardly be disputed by any intelligent observer. It is when he begins to draw inferences from it that the Taoist parts company from the average Christian. Believing, as he does, that the visible Universe is but a manifestation of the invisible Power behind It, he feels justified in arguing from the known to the unknown, and concluding that, whatever Tao may be in itself (which is unknowable), it is certainly not what we understand by a personal God--not a God endowed with the specific attributes of humanity, not even (and here we find a remarkable anticipation of Hegel) a conscious God. In other words, Tao transcends the illusory and unreal distinctions on which all human systems of morality depend, for in it all virtues and vices coalesce into One.

The Christian takes a different view altogether. He prefers to ignore the facts which Nature shows him, or else he reads them in an arbitrary and one-sided manner. His God, if no longer anthropomorphic, is undeniably anthropopathic. He is a personal Deity, now loving and merciful, now irascible and jealous, a Deity who is open to prayer and entreaty. With qualities such as these, it is difficult to see how he can be regarded as anything but a glorified Man. Which of these two views--the Taoist or the Christian--it is best for mankind to hold, may be a matter of dispute. There can be no doubt which is the more logical.

-- Lionel Giles, Introduction to The Book of Lieh-Tzü

#Daoism#tao#taoism#hegel#Lieh-Tzü#Liezi#Christianity#christian mysticism#chinese philosophy#Deacon#German idealism#Terrence Deacon#Steps to a Metaphysics of Incompleteness#metaphysics of incompleteness#theology#Religion#history of religion#God#incompleteness#marx and mysticism

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

“If then you do not make yourself equal to God, you cannot apprehend God; for like is known by like.

Leap clear of all that is corporeal, and make yourself grown to a like expanse with that greatness which is beyond all measure; rise above all time and become eternal; then you will apprehend God. Think that for you too nothing is impossible; deem that you too are immortal, and that you are able to grasp all things in your thought, to know every craft and science; find your home in the haunts of every living creature; make yourself higher than all heights and lower than all depths; bring together in yourself all opposites of quality, heat and cold, dryness and fluidity; think that you are everywhere at once, on land, at sea, in heaven; think that you are not yet begotten, that you are in the womb, that you are young, that you are old, that you have died, that you are in the world beyond the grave; grasp in your thought all of this at once, all times and places, all substances and qualities and magnitudes together; then you can apprehend God.

But if you shut up your soul in your body, and abase yourself, and say “I know nothing, I can do nothing; I am afraid of earth and sea, I cannot mount to heaven; I know not what I was, nor what I shall be,” then what have you to do with God?”

― Hermes Trismegistus, Hermetica: The Greek Corpus Hermeticum and the Latin Asclepius

#analogy#principle of analogy#as above so below#hermetica#corpus hermeticum#Hermetic#hermeticism#hermetic philosophy#charles darwin and the hermetic tradition#marx and mysticism#Karl Marx and Human Self Creation#God#immanentism#History of Philosophy#history of science#as within so without#Alchemy#buddhism#divine union#mysticism#meditation

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Terrence Deacon on Literacy and "Learning Disorders"

youtube

Literacy is an interesting case because, of course, there was no time for literacy to have evolved biologically... Writing didn’t show up until just a few thousand years ago... this is a case of, in effect, abilities that were already there being utilised for this...

But what we now stigmatize; dyslexia, alexia, writing problems and so on, in calling it a “disorder”, what we’ve done is we’ve, in a sense, renamed human variation: There was never selection for this, we were not “meant” to do this, so to speak; so that, in fact, the fact that we do it is a miracle.

#Deacon#Terrence Deacon#literacy#language#biosemiotics#complexity#evolution#evolutionary theory#evolutionary biology#Neuroscience#anthropology#learning#learning disorder#disabilties#writing#biology#sociobiology#dyslexia#alexia#natural selection#semiotics#semiosis#Biosemiotic theory#incomplete nature#neurobiology

1 note

·

View note

Text

James Tabor on Dualism: The Bad Idea That Took Over the World... And Came to Be Seen as the Only Thing Which Counted as “Religion”

youtube

In this 2015 lecture I talk about the ways in which dualistic forms of thinking about the cosmos, often referred to as “Enochian” in their Jewish forms, and “Gnostic” in the wider Hellenistic world, basically took over the Western world and fundamentally transformed Judaism, Christianity, and Islam into religions of “cosmic salvation,” rather than ethical transformation of this world–what Judaism calls Tikun Ha-‘Olam.

My University of Chicago teacher, Jonathan Z. Smith, characterized this as a shift from the “locative” view of human place, vs. the “utopian,” in which a heavenly world beyond became the focus. His classic essay in the Encyclopedia Britannica on “Hellenistic Religion” offers quite an amazing overview of the core idea. [1]. This video has proven to be enormously popular, with many loving it and others viewing the shift as anything from “bad,” which is my own characterization. For many this sort of dualism is the very “definition” of what religion is all about–so thoroughly has dualism triumphed worldwide. The focus of the Hebrew Bible on “this world,” in contrast to an imagined “world beyond” has become a unique perspective–one that many forms of Judaism has largely lost or rejected.

In one of my earliest published articles I offered some personal reflections in this matter in the Journal of Reform Judaism, titled “Reflections on the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament,” with a response from Michael Signer.

-- James Tabor, The Bad Idea that Took Over the World

#James Tabor#Dualism#marx and mysticism#Karl Marx and Human Self Creation#Christianity#early christianity#christian mysticism#Gnostism#enochian judaism#western esotericism#history of religion#History of Philosophy#Religion#philosophy#Diesseitigkeit#marx#biblical studies#neoplatonism#imperfection#immanentism#transformation#judaism#Hellenistic Religion#Jonathan Z. Smith#hebrew bible

3 notes

·

View notes