#Homeric myth

Note

Dear Professor, elsewhere you mentioned teaching Miller, Barker and Atwood and I was wondering if you could expand a little on your thoughts on their respective retellings.

QUEERING AND FEMINIZING HOMER: MILLER, BARKER & ATWOOD

For my “Ancient Greece in Modern Historical Fiction” course, I assigned three texts that all dealt with the Homeric poems, in order to examine how ancient myth can be reappropriated for modern audiences. These were Madeline Miller’s The Song of Achilles, Pat Barker’s The Silence of the Girls, and Margaret Atwood’s The Penelopiad.

There are a lot, and I do mean a lot of retellings of the Iliad or Odyssey. Some, maybe most, do so in a straightforward way, treating the myth like an historical novel. They may try to resituate it in another head, like Helen’s, or Hektor’s, or even Paris’s. But they don’t, otherwise, change much. If anything, they attempt to eliminate the fantastical elements (like gods) and play the story as if it really happened.

Yet the nature of myths makes them different from historical fiction. The latter, for me, has a much higher bar for detail accuracy. A myth begins as fiction, so while I do appreciate various renditions attempting historical accuracy, I don’t see it as essential to a good retelling. And the three novels I chose mostly don’t track in that direction; all retain gods and heroes and at least the patina of the magical.

Part of why I’m less concerned with historical accuracy owes to the fact Homer* wasn’t. It’s hard to have accuracy when the original text was all-over-the-place.

Homer composed a stunning piece of war fiction in terms of its impact on a soldier’s psyche. But it’s crap historical fiction. Let’s just put that out there at the start. Imagine putting Al Capone and 1920s gangsters in Elizabethan England, or maybe, Queen Elizabeth in 1920s Southside Chicago. That’s the time and cultural differential. He’s theoretically writing about events at the tail end of the Bronze Age (c. 1200-1100), but the social structure reflects the Early Iron Age as well as the Late Iron Age, with a few vestiges of the Bronze Age. But accuracy isn’t the *point*, for Homer.

Another point of clarification: the Iliad and Odyssey are about fictional people. There was no Agamemnon, Achilles, Priam, Hektor, or Helen. The Trojan War probably did happen—but not for the reasons or in the way the story relates. It’s a bit like Saving Private Ryan: WW II certainly happened, but Private Ryan is Everyman Lost.

Last, the basic plots of the Iliad and the Odyssey were not invented by Homer. These were well-known epic stories. Homer’s brilliance lay in what he did with them. Ergo, it’s more correct to speak of Homer as the composer of the Iliad and Odyssey, rather than the author/writer.

Therefore, what I’m looking for in modern retellings is what a MODERN author does with the same story. How does she or he use these familiar stories to talk about our present age…which is what Homer did himself, after all.

I’ve talked elsewhere about some issues I have with Miller’s Song of Achilles, but as is probably evident from what I said above, I have absolutely zero problems with her queering the tale. What I find more interesting is how her adaptation of Achilles and Patroklos as lovers speaks to our modern world and modern needs.

Any retelling of the Iliad today will run up against the brick wall of ancient values that were very different—and often rather repugnant—to modern readers. To ancient minds, Achilles was a HERO. Admirable. Worthy of emulation. To modern readers he’s, well, kind of a dick. And a butcher.

I’d submit that Homer meant him to be a jerk, too. Part of Homer’s lasting value is his ability to take a cultural hero and finesse him until he’s maybe not so hero-ish, but still comprehensible in his actions to listeners who had, themselves, experienced combat. Ergo, Homer’s Iliad still has something to say today to Vietnam Vets (as per Jonathan Shay’s brilliant Achilles in Vietnam). But most modern readers are not going to like the guy. He has a terrible temper, throws fits when thwarted, and is repeatedly described as “man-killing” like it’s a compliment.

So, as a modern author with a modern audience, how do you redeem him? (If you redeem him; not all authors choose to.)

Miller turned the Iliad into a love story, told from Patroklos's POV, which makes Achilles more likeable. He's painted by Patroklos’s adoration. In both Miller’s retelling and Homer’s original, Patroklos is depicted as empathic in a way modern readers can get behind, so he’s a good choice of point-of-view character. Yet although he comes off as your basic “nice guy,” in the original he is also a skilled warrior who kills a lot of people. Miller ignores this, making him a healer, not a fighter.

Like her casting of Thetis as bitchy, I have some issues with her decision to avoid dealing with the more brutal parts of Homer’s epic by eliding it. She’s buffed off the ugly rather than confronting it. It winds up feeling like a puff piece, alas, which I don't believe was her intention.

Why it does succeed owes not to the fact it’s a love story, but a queer love story. In antiquity, Achilles was a prince (as was Patroklos): the elite of the elite, the ruling class and conquering heroes. They were, in no way, an oppressed minority. A “subaltern” group.

Yet today, queer people are a subaltern population, although people in the queer community enjoy differing degrees of social acceptance. A black or brown trans woman experiences a great deal more oppression than a white gay guy. Yet public acceptance of queerness in any form is relatively recent, as in, something I’ve seen occur in my lifetime. And of course, now it’s being pushed back against.

So to have heroes who did occupy the ruling class and didn’t have to apologize for who they loved is important. If Achilles is a dick, well, he’s a gay dick (pun intended), and pretty, so we’ll slip him a pass.

Is that wrong? Homer doesn’t have a copyright on Achilles. Or Patroklos. Just as he used Achilles and Hektor and Priam to his own ends, so does Miller. Yet I am bothered by her ducking of the fundamental violence of the Iliad. Homer doesn’t, and it makes his the superior story. (Although topping Homer is rather a high bar.) Grief (and rage) make Achilles into a monster. Empathy redeems him…but it’s not empathy for Patroklos. In fact, his inability to empathize with Patroklos’s own grief gets his friend killed. Homer doesn’t sugar-coat that.

No, it’s empathy for the enemy—for Priam, when Priam evokes the grief Achilles’s own father will feel—that finally gets through to him. It re-humanizes him. He and Priam cry together.

See what Homer did there? That’s why the poem is still read c.2700 years after it was composed. On certain levels, it’s timeless. By contrast, Miller’s rendering is time/situation-dependent. It succeeds now. It wouldn’t have succeeded 50 years ago, if it had even got published, and I’m not sure it’ll be as relevant 50 years in the future. That’s not a condemnation. Sometimes books become important when they’re needed.

Yet, as I have issues with her ducking the story’s inherent violence, I also had issues with her handling of Thetis as one of only two prominent women in the novel. Again, there’s no copyright on Thetis, but in Greek myth, she’s not a cold bitch—in fact, she’s rather the opposite. So, while I think Miller’s queering of the Iliad had positive current social coin, her treatment of Thetis played into negative tropes about women (and mothers) that troubled me.

These are things I invite my students to wrestle with, when we talk about The Song of Achilles.

Btw, I sometimes see Miller grouped with Barker and Haynes and Atwood as “feminist” retellings of the Iliad. In no way is her book a feminist retelling. A queer retelling, but not a feminist one.

Let’s turn then to Barker. The very title of Barker’s book gives us a hint of what she wants to accomplish. The Silence of the Girls recasts the myth as the story of Briseis, Achilles’s war prize. Barker’s is one in a line of attempts to present the Iliad from a woman’s point of view, which goes back at least to Marion Zimmer Bradley’s 1987 Firebrand. Just as June Rachuy Brindel told Ariadne’s story (and Phaedra’s too) from a feminist perspective 40 years before Jennifer Saint (and was nominated for a Pulitzer). Another, more recent approach to this was Natalie Haynes’s A Thousand Ships, published just a year after Barker.

[A point: two books published a year apart do not owe to each other. It takes years to write, then publish a novel. But they may reflect current publishing perceptions of market interest.]

Barker makes a concerted effort to take a feminist look at the myth by centering Briseis as the narrator…but only for the first part. By part two, Achilles elbows his way in. Suddenly, it’s no longer Briseis’s story once she’s carted off to Agamemnon’s tent. It seems that Barker just couldn’t unhook entirely from centering Achilles, even if he’s more anti-hero.

We can consider this several ways. It’s possible that she didn’t want Achilles to be as simplistic as Briseis saw him, and therefore needed to get out of Briseis’s head in order to suggest more nuance. It’s also possible that she really does mean her title, The Silence of the Girls, and so silences the girl narrator when handed off to Agamemnon.

I have problems with both readings. First, the need to cast Achilles as more complex than Briseis wants to read him moves the needle away from the female/feminist perspective. Why should it be necessary to give Achilles depth if it’s Briseis’s story we’re telling? Unless she eventually comes to see depth in him…in which case, show us how she comes to that conclusion.

And if she really wanted to “silence” the girl when she became a slave, silence her THEN, not just when she moves residence. She’s no more a slave under Agamemnon than under Achilles. She might lack Patroklos’s support and semi-understanding, but her basic situation has not changed enough to justify a significant change in narrator.

To me, it just seems that Achilles sucked up all the air in the room, as he’s wont to do. He took over her story because Barker let him. It’s still a male-centric view.

This may have happened because Barker, like Miller, didn’t know enough history of the period to thoroughly reimagine the story she’s telling. In this respect, a little more historical accuracy—if not necessary—may have been helpful. How? By recentering the story not only on the female voice(s), but also on non-Mycenaean/Greek voices. Her opening was incredibly interesting, and could have had much more done with it. Marauding Greeks raze her town and take her captive. She comes from a satellite kingdom of the rich and powerful city of Wilusa (Troy), part of the Arzawa confederacy, itself a sometime-tribute group of the even more powerful Hittite Empire. The Mycenaeans are essentially pirates, hated by Hitties (and their allies?). It might have given Barker a two-pronged way to anchor her narrative more solidly: non-male AND non-Greek.

As noted, attempts at historical situating isn’t required. But Barker’s take ended up bogged down by the original Greek-centric view. She wanted to un-silence the girls, but unfortunately, by my reading, she only continued Achilles’s dominance.

So, I see both Miller’s and Barker’s attempts as not quite succeeding—which is interesting in itself. The books are hardly failures, or they wouldn’t have sold so many copies. And they do, in their own ways, take on Homer to resituate it for our era. But neither can quite get away from the historical value systems that make the Iliad problematic to modern readers.

Then we have Margaret Atwood, who takes us to school.

Folks, The Penelopiad is how you give voice to subaltern populations. For such a short book, it has wonderful layers.

First, this is not set in antiquity. Penelope tells her story from Hades, in the “now,” because she wants to correct Homer’s presentation of her (even though Homer’s presentation is overall rather favorable). The tone is modern and discursive. Some find it annoying, but she chooses it for a reason. While the book is not a comedy (unless black), it’s full of intentional, sarcastic humor.

Thousands of years have passed since the events of the Iliad and Odyssey. Penelope remains in Hades, not choosing to be reborn, unlike most of her contemporaries, including her husband…a nice nod to Plato’s Myth of Er where Odysseus is one of several souls who choose rebirth. I don’t know if Atwood is familiar with the story, but it’s Atwood, so it wouldn’t surprise me if she is. It’s an “Easter Egg” the average reader won’t get. Doesn’t matter. Atwood litters her novel with allusions to Greek myth, drama, and philosophy, as well as modern anthropology and Classics. None of it is necessary to follow her tale, but the more you know, the more you’re going to get from it. And the harder you’ll laugh (she spoofs Robert Graves’ White Goddess).

Most of the narrative is Penelope’s metafiction first-person account, but her chapters are broken up by a “chorus” of Penelope's twelve maids, actual figures from the Odyssey, mostly unnamed. Atwood uses them exactly as a Greek chorus in a traditional tragedy (which is what she’s writing). In Homer, the handmaids were traitorous little sluts, as ancient Greek men tended to see slaves, especially slave women. Atwood does something brilliant with them.

The Penelopiad lets women take over the narrative in a way Barker attempted but didn’t quite manage. If the men, Odysseus and Telemechus, are present, Atwood never lets them have a POV. Only Penelope or her maids narrate, and she sets those in tension. Like Briseis, Penelope is a member of the elite: a princess, then queen, however she presents herself in contrast to Helen. She’s a “poor little rich girl.” The twelve maids are manifestly not.

As the story unfolds, Atwood cleverly reminds us of something deeply embedded in Homer: these characters LIE. Odysseus is a magnificent liar, and Penelope lets us know it. “Bent-minded Odysseus” is the typical way he’s described by Homer, and it’s meant as a compliment. Even today, in Greece, being “clever” is better than being “smart.” Homer’s “bent-minded Penelope” is his match. He draws a sympathetic picture of her as Odysseus’s true partner, even if Odysseus entertains dalliances on the side. Of course, in that world, it was expected. Penelope is loyal, waiting at home…not unlike Penelope waiting in Hades here, never venturing out into new lives.

But we must remember: As Odysseus lies about his exploits and life, Penelope lies, too.

As we begin the book, the temptation for the reader—as Atwood intends—is to take Penelope’s account at face value. We may think we’re reading a novel that upends the narrative, centering female voices at last! But as the book continues, the chorus of maids presents us with a different tale, a different view. Then we reach the end and realize what Atwood has so cleverly done.

She truly decentered the narrative.

She’s not just telling Penelope’s story. She’s also telling what happened to the slave women, the twelve maids, who were hanged by Odysseus and Telemachus—in the original epic because they betrayed their mistress/Ithaca by consorting with the suitors. Here, Penelope, who’s just trying to survive, asks them to consort with the suitors to gain intelligence, and some are raped as a result. In the end, they’re executed along with their “lovers.” And Penelope didn’t step in to save them.

They’re expendable.

This is not just a Greek tragedy, but a horror story. Atwood reminds us that although Penelope may be less powerful than her husband, the King of Ithica, she is NOT truly disempowered. She is only half-subaltern. The maids, who are both women and slaves, are the truly disenfranchised. All they have in the world are their looks, and the protection of their mistress…which she doesn’t give.

So, they die.

Most people reading the Odyssey never think about the hanged maids—whether it was a just punishment. It happens in the background; they’re traitors like the suitors. But after reading Atwood, you’ll never read that poem again and overlook them.

Atwood’s novel is not romantic, not poetic, not inclined to have readers read and re-read it to get lost in the romance all over again (as with Miller’s). It’s deeply disturbing. And it’s meant to be.

Of these three novels, this is the one that will still be read, and resonate, fifty years down the road. This is the retelling of Homer that actually manages to unseat the accepted narrative and makes us re-examine the story from the real flip-side.

This one actually “unsilences” the (twelve) girls.

-------------------------

*I’m not going to touch the question of whether there was a “Homer,” and if so, was it one or two people, a he or a she, etc. There is a veritable tsunami of writing about who “Homer” may have been and the composition of these poems. Just be aware.

#Madeline Miller#Song of Achilles#Pat Barker#Silence of the Girls#Margaret Atwood#Penelopiad#modern takes on Homer#Homeric myth#Classics#Briseis#Achilles#Patroclus#Patroklos#Achilles in Vietnam#Ariadne#Penelope#Odysseus#subaltern voices#reception studies#reception of Homer#Queering Homer#Feminizing Homer#tagamemnon

198 notes

·

View notes

Text

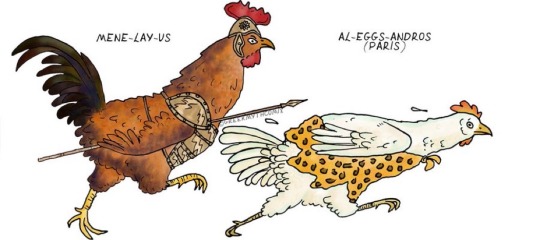

To explain my chicken obsession:

* * *

Me: I’m enjoying drawing chickens for this commission.

Husband: ha ha Greek Myth Chickens!

Me: 🤔

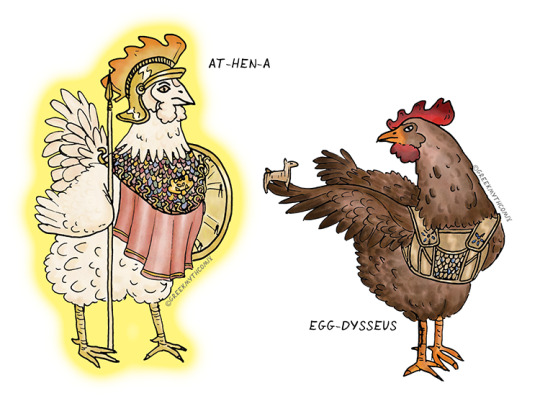

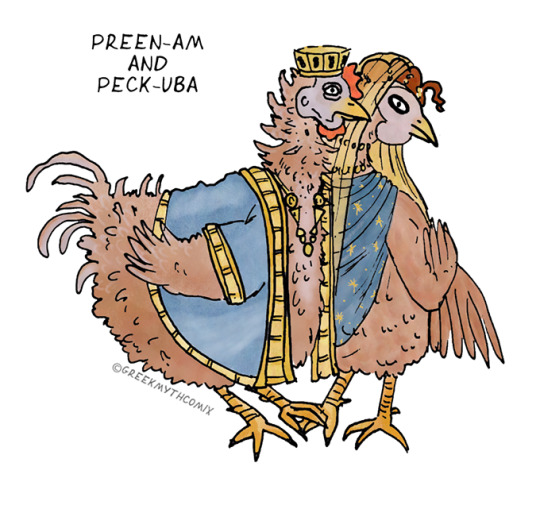

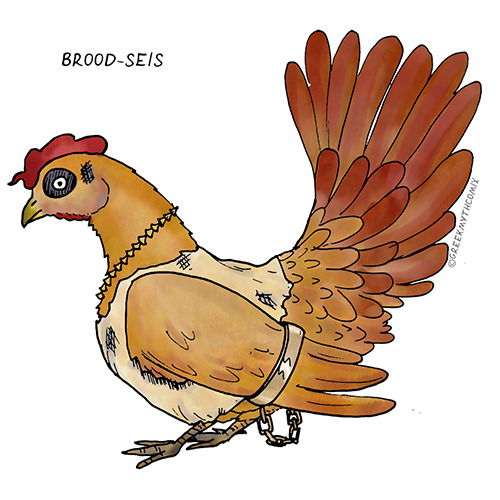

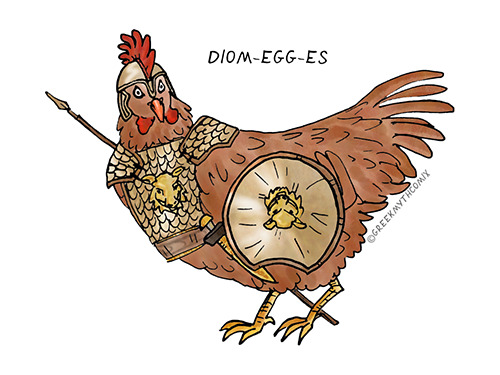

I now present to you,

🏺Greek Myth Chickens 🐓

ILIAD EDITION

(drawn and originally posted in May 2021, coloured and reposted Jan 2023)

1) Egg-chilles and Patro-cluck (Achilles and Patroclus)

2) Mene-lay-us and Al-eggs-andros (Paris) (Menelaus and Alexandros [Paris])

3) Egg-amemnon (Agamemnon)

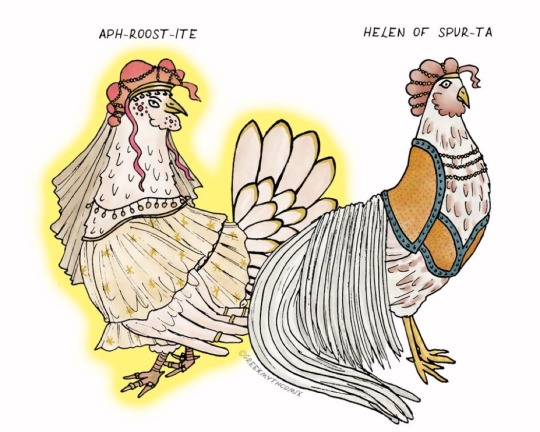

4) Aph-roost-ite and Helen of Spur-ta (Aphrodite and Helen of Sparta)

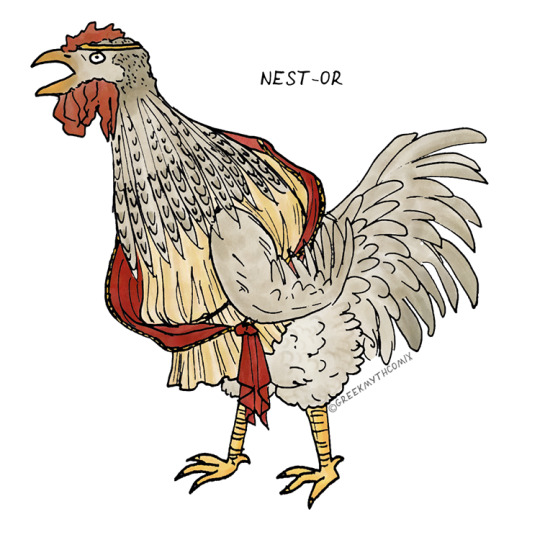

5) Nest-or (Nestor)

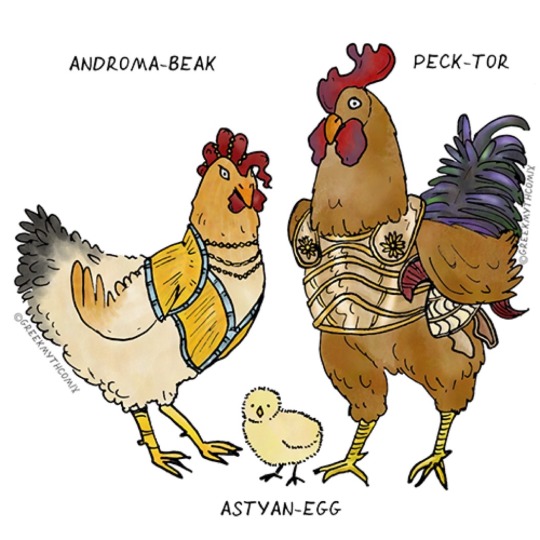

6) Androma-beak, Peck-tor, and Astyan-egg (Andromache, Hektor and Astyanax)

7) At-hen-a and Egg-dysseus (Athena and Odysseus)

8) Preen-am and Peck-uba (Priam and Hekuba [Hekabe])

9) Brood-seis (Briseis)

10) Diom-egg-es (Diomedes)

EDIT: Greek Myth and Roman History chicken MASTERPOST - https://www.tumblr.com/greekmythcomix/725538723329179648/greek-myth-roman-history-chickens-master-post Here Be More Chickens Cosplaying

(See next post for last 3 Iliad chickens- https://www.tumblr.com/greekmythcomix/722218945873051648/iliad-chickens-continued-11-lay-jax-tel-capon )

#Achilles#Patroclus#patroklos#akhilles#greek mythology#greek myth retellings#greek myth#comix#greek myth memes#Iliad#Homer#artwork#my artwork#Greek myth chickens#illustration#pun#fanart#chickens#tagamemnon#the Iliad#classics#classical civilisation

11K notes

·

View notes

Text

Young Odysseus introduces his son to the goddess Athena

(Alternative title: Telemachus meets his fairy Godmother)

Creator’s note:

Does this picture look blurry to you? Like even if you click on the image to enlarge it? I don’t know why but I can’t seem to get tumblr to show the full resolution image. I worked hard to make faces that actually look like faces for once but now they’re just blurry blobs 😭. Anybody know how to fix? EDIT: thank you all for the feedback! I’m glad it is not blurry for you!

#the odyssey#odyssey fanart#odysseus#telemachus#tagamemnon#greek mythology#greek mythology fanart#greek myth art#Athena#greek gods#epic the musical#The iliad#Trojan war#homers odyssey#classics

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

Long hair won out in the end rip all the short haired Menelaus truthers

Art used as reference from littleulvar on twitter: https://twitter.com/littleulvar https://twitter.com/littleulvar/status/1210636583713591296

#His hair is looking ORANGE#Homer like his hair is auburn :/ it’s auburn if u reduce the saturation smh#He turned out weirdly viking esque?? I think it’s the braided hair ??#Majestic if I do say so myself#Menelaus#greek mythology art#my art#the Iliad#trojan war#Greek myth#a#Also an ATTEMPT was made at Bronze Age armour#I don’t know if my reference was reliable#fuck it we ball

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

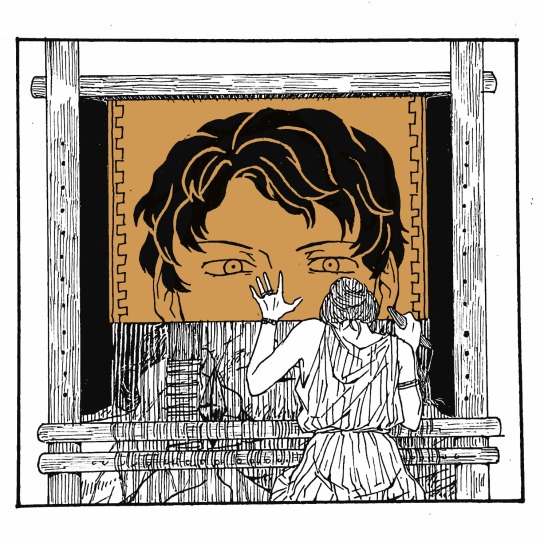

What returned and what did not return.

#Odysseus#Penelope#homer#the odyssey#ancient greece#greek mythology#ancient greek mythology#greek myth art#greek myth#ancient greek myth

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

I will never understand how Odysseus has all the braincells while also having none of them at the same exact time. He is an amazing war general and is insanely smart but has the attention span of a rat fuelled by the need to cause chaos simply because he is bored. He can't listen to one thing while getting distracted by the thing he was specifically told not to touch.

#this man will forever be an enigma#odysseus#the odyssey#homer's odyssey#the iliad#homer's iliad#ancient greek mythology#greek mythology#ancient greek#greek myth#greek mythology memes#greek myth memes#greek heroes#greek stuff#greek posts#greek blog#epic the musical#epic: the musical#epic the troy saga#epic: the troy saga#epic the cyclops saga#epic: the cyclops saga#epic the ocean saga#epic saga

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Odysseus x2 for @wolfythewitch .

I had so much fun making these I love him so so much.

#Odysseus#the odyssey#homer#art#comms are open and you get 50% off if you order smth anc greek myth related.

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

shooting me in the heart would’ve been easier but okay

#don’t mind me i’m going to cry in a corner now#greek mythology#greek myth#odysseus#penelope odyssey#odypen#odysseus and penelope#the odyssey#homer

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

#my memes#trojan war memes#the trojan war#athena#apollo#the iliad#homer#greek mythology#greek myths#athena deity#apollo deity#pjo apollo#pjo athena#prince hector#diomedes#odysseus#paris#helen of sparta#menelaus#agamemnon#achilles#patroclus

986 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alrighty class, just before we begin Book 22, I want to remind you it was not ‘based’ or ‘goated’ of Achilles to desecrate Hector’s corpse by dragging it through the dirt on the back of his chariot. The only ‘slay’ he ‘served’ was literally slaughtering half the Trojan army.

#tagamemnon#the iliad#achilles#hector#homer#trojan war#greek literature#greek mythology#ancient greece#classics#iliad#greek myths#classical studies#classical mythology

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

Sing O goddess, of Hera's rage, how they vilified her for it, even if she was a woman betrayed. Sing O goddess, of Helen's desire, how everyone forgot she was the daughter of the most powerful God and that was what made the whole world burn. Sing O goddess, of Hestia's fires, how she left the cruelty of Olympus for a peaceful life - how she gave Prometheus the idea to steal the sacred flames for the mortal world. Sing O goddess, but not of Odysseus or Menelaus, Achilles or Agamemnon. Sing instead of women full of fire. Sing us the torch song which brings wildfire when Goddesses like you are ignored.

Nikita Gill, Great Goddesses 2

#spilled ink#greek mythology#hera#helen#hestia#greek myth#writing#poetry#words#great goddesses#poem#feminist quotes#feminist literature#feminist books#homer

962 notes

·

View notes

Text

You Are Odysseus

So

I’m a teacher of Classical Civilisation that has taught the Odyssey for over a decade and studied pretty much every myth and story with Odysseus in it.. I think

and I’m writing an Interactive Fiction (choose your own path) version of the Odyssey, inspired by the Homeric phrase “he turned his great heart this way and that”, where you are Odysseus, allowing you to follow his decisions or make your own

and it already has 400 sections to it - written to emulate modern translations of the Odyssey, including the literary features of simile, formula, epithet, and the rest - and 21 different ways to die, and quite a lot of period and theme-appropriate alternatives

(and if I get time, the option to be Telemachus or Penelope, although that might have to wait because it’s already a monster)

and I’ve tested what I’ve made so far on my pupils, other Classics teachers, and some of the leading (and best-read) Greek Mythology podcasters and YouTubers, all of whom have universally loved it (yay!)

(EDIT: Oops and I presented on it at the Classical Association conference last year)

I’m trying to finish it this summer, but need a bit of encouragement to do so

EDIT: and I forgot to say that ideally I’m planning on it being a beautiful BOOK with an old-fashioned cover and lots of ribbons to mark your place ❤️ (ex-bookseller ofc)

so, please let me know if you’d like to know more!

(EDIT: or sign up here go get notified directly when it’s ready: https://ljenkinsonbrown.wordpress.com/you-are-odysseus-signup/ )

#odyssey#greek mythology#greek myth#tagamemnon#greek myth retellings#homer#interactive story#interactive fiction#classics#classical literature#classical civilisation#odysseus#writing#gamebook

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Odyssey, but if Odysseus just got to stay home and chill with his son and goddess bestie.

been obsessing over this musical project lately.

Can't stop imagining the moments Odysseus missed. Little mischievous joys, teaching moments etc. In this scene, Odysseus teaches Telemachus how to braid hair and Athena shares profound wisdom with two of her favorite mortals.

#Epic the musical#Athena#Telemachus#the Odyssey but happy#odysseus#the odyssey#odyssey#ithaca#greek mythology#greek myth retellings#greek myth art#odyssey fanart#fanart#my art#trojan war#tagamemnon#the iliad#Iliad#homers odyssey#homers iliad

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

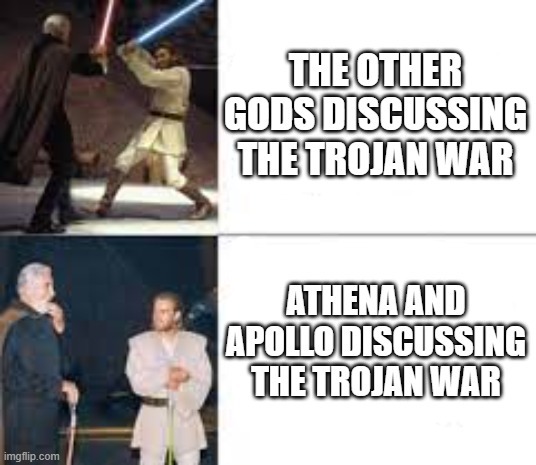

Doodle of Achilles and Ajax playing dice based on this black figure vase painting by Exekias

#Quality cousin time#Is ajax huge or is Achilles just tiny: the game#The only straight haired Homeric heroes I’ve drawn#Achilles is anticipating dodging the board when Ajax inevitably flips it#Ajax the greater#Achilles#greek myth#my art#greek myth art#achilles art#This vase has such foreboding energy yknow with the full black border and the fact that neither of them live to see the end of the war#And a moment of downtime in the Trojan war between two family members yknow#My doodle does NOT have the same energy lmao#The iliad#trojan war

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Isn't it freaking adorable how both Odysseus and Penelope could remember down to exact detail what clothing she had packed for Odysseus before he left for war even 20 years later?!

😭😭😭😭😭😭😭😭😭

And she packed them herself. She didn't use the help of any servant or slave to do it. She wanted to prepare her husband herself. What is even more is that all the clothes were of vibrant colors which had me thinking;

What if Penelope deliberately prepared vibrant colored clothes for Odysseus solely so that she could see him from afar for as long as possible?! And man I can so imagine her doing the same! Like standing on the top of the hill where the palace is, wearing a vibrant dress that floats in the wind, holding baby Telemachus in her arms and watch Odysseus's bright tunic on the ship and Odysseus turning his head to look up at that aetherial figure on the hill almost leaning over the ship to see her JUST FOR A LITTLE LONGER until he cannot see her anymore and this is where he keeps looking at his island becoming smaller and smaller to the horizon, shedding tears of goodbye

🥺🥺🥺🥺🥺🥺🥺🥺🥺🥺🥺🥺🥺🥺

Man ninjas are cutting onions around me again!!!

#greek mythology#odysseus#the odyssey#greek myth#odyssey#the iliad#iliad#odypen#odysseus and penelope#the odyssey 1997#trojan war#ithaca#telemachus#tears of goodbye#war#odysseus leaving ithaca is probably one of the saddest moments in greek mythology#odysseus the sailor#odysseus the master mariner#penelope won't see her husband's face for another 2 decades#sad separation#separation#odysseus and penelope make the world go round#tagamemnon#odysseus father of telemachus#homeric poems#homecoming odysseus#homeric epics#homer

284 notes

·

View notes

Text

sometimes I wonder just how sexy Odysseus would have to be to get Penelope, probably some of the Achaean men at war, circe AND calypso to fall in love/be with him for quite a while and then I look at @wolfythewitch 's art and know the answer

#it's also cause he's a liar with help from the gods but shh#the odyssey#wolfythewitch#odysseus#greek myth#mythology#homer#art

858 notes

·

View notes