#Pat Barker

Text

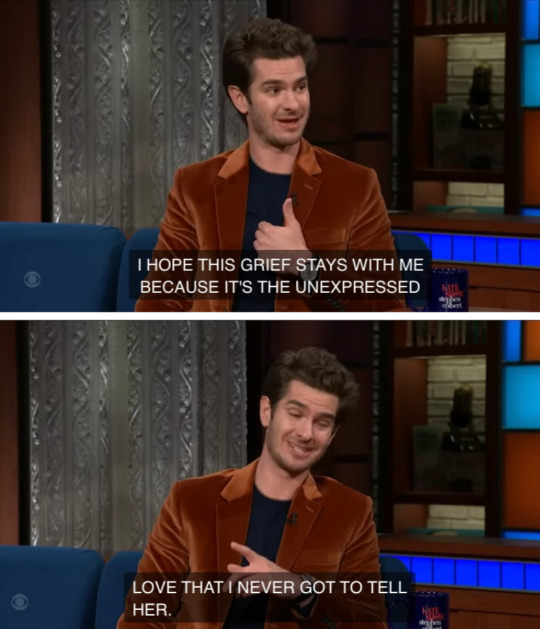

love warrior, glennon doyle melton / fleabag (2016-2019), dir. phoebe waller-bridge / shannon barry / andrew garfield for gq’s men of the year 2022 / jamie anderson / not quite here, hannah lock / ocean voung / holly warburton / andrew garfield, the late late show with james colbert / silence of the girls, pat barker

#web weaving#on grief#love warrior#fleabag#andrew garfield#hannah lock#ocean vuong#holly warburton#silence of the girls#pat barker#words#*#bro.#mine: web weaving

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

Cut a chrysalis open, and you will find a rotting caterpillar. What you will never find is that mythical creature, half caterpillar, half butterfly, a fit emblem of the human soul ... No, the process of transformation consists almost entirely of decay.

- from Regeneration, Pat Barker

110 notes

·

View notes

Text

Because the story of your life // becomes your life

- Lisel Mueller

Phoebe Bridgers, I Know The End / Augusto Boal, Theatre of the Oppressed / Lisel Mueller, Why We Tell Stories / Sleeping at Last, East / Pat Barker, Silence of the Girls / Brandon Melendez, How to Write the Quantum Mechanics Uncertainty Principle into a Promise to Return Home / Lisel Mueller, The Story / Richard Siken, Litany in Which Certain Things are Crossed Out

#web weave#webweaving#poetry#Lyrics#literature#Phoebe Bridgers#sleeping at last#pat barker#richard siken#lisel mueller#brandon melendez#augusto boal#storytelling#writblr

286 notes

·

View notes

Text

The "I should buy another bookcase" situation is becoming acute.

#books#home library#adultbooklr#jane austen#orhan pamuk#salman rushdie#p. g. wodehouse#victoria mackenzie#pat barker#margaret atwood

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

pat barker // @/strangebiology // the foundations of decay - my chemical romance // kellie smith // forest clouds - windhand

#parallels time baby#a.txt#parallels#pat barker#vulture culture#my chemical romance#windhand#kellie smith#animal death#tw dead animal#animal death /#dead animal tw#100+

474 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sometimes, Helen would go into the inner room even before I left and then I’d hear the chattering of the loom, the rattle as the shuttle flew to and fro. There was a legend—it tells you everything, really—that whenever Helen cut a thread in her weaving, a man died on the battlefield. She was responsible for every death. And then, one day, she showed me her work. I’ve known some great weavers in my life, including some of the women in the camp. The seven girls Achilles captured when he took Lesbos—they were brilliant, no other word for it, they were brilliant. But even they weren’t as good as Helen. I wandered round the room looking at the tapestries while Helen sat at the loom and sipped her wine. Half a dozen huge battle scenes covered the walls, a sequence that taken together told the whole story of the war so far. Hand-to-hand combat, men decapitated, gutted, skewered, filleted, disembowelled; and, riding high above the carnage in their glittering chariots, the kings: Menelaus, Agamemnon, Odysseus, Diomedes, Idomeneo, Ajax, Nestor.

I knew Menelaus had been her husband, before she ran away with Paris, but her voice didn’t change when she said his name. Did she point to Achilles that day? I think she must’ve done, but I really don’t remember. The Trojans were there too, of course, Priam looking down from the battlements, and below him, on the battlefield, his eldest son, Hector, defending the gates. No Paris, though. Paris seemed to be fighting the war from his bed. On the rare occasions I saw them together, it was obvious even to a child that Helen preferred Hector to Paris, whom I think she’d grown to despise. His reluctance to go anywhere near the battlefield was notorious, as was Hector’s contempt for his brother’s cowardice. When I’d finished walking round the tapestries, I went round again because I wanted to check something I didn’t understand.

“She’s not there,” I said to my sister that night after dinner. “She’s not in the tapestries. Priam’s there—but she isn’t.”

“No, well, of course she isn’t. She won’t know where to put herself till she knows who’s won.”

#perioddramaedit#lyrics#history#lana del rey#helen of sparta#helen of troy#the silence of the girls#pat barker#greek mythology#the trojan women#the trojan war#diane kruger#troyedit#troy 2004#achilles#paris of troy#hector of troy#perioddramacentral#period drama#ancient history#perioddramasource#perioddramasonly#old money#mythology#homer#the iliad#briseis#priam of troy#odysseus#helen and paris

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Give my body to the fire, bury me in the golden urn your mother gave you. It’s big enough for two. Let’s be together in death as we did in life.”

Patroclus to Achilles in The silence of the Girls by Pat Barker.

“When I am dead, I charge you to mingle our ashes and bury us together.”

Achilles to his soldiers after Patroclus’ death in The song of Achilles by Madeline Miller.

#patrochilles#achilles#pat barker#patroclus#tsoa#madeline miller#the silence of the girls#greek retelling#greek mythology#dark academia#history

149 notes

·

View notes

Note

Dear Professor, elsewhere you mentioned teaching Miller, Barker and Atwood and I was wondering if you could expand a little on your thoughts on their respective retellings.

QUEERING AND FEMINIZING HOMER: MILLER, BARKER & ATWOOD

For my “Ancient Greece in Modern Historical Fiction” course, I assigned three texts that all dealt with the Homeric poems, in order to examine how ancient myth can be reappropriated for modern audiences. These were Madeline Miller’s The Song of Achilles, Pat Barker’s The Silence of the Girls, and Margaret Atwood’s The Penelopiad.

There are a lot, and I do mean a lot of retellings of the Iliad or Odyssey. Some, maybe most, do so in a straightforward way, treating the myth like an historical novel. They may try to resituate it in another head, like Helen’s, or Hektor’s, or even Paris’s. But they don’t, otherwise, change much. If anything, they attempt to eliminate the fantastical elements (like gods) and play the story as if it really happened.

Yet the nature of myths makes them different from historical fiction. The latter, for me, has a much higher bar for detail accuracy. A myth begins as fiction, so while I do appreciate various renditions attempting historical accuracy, I don’t see it as essential to a good retelling. And the three novels I chose mostly don’t track in that direction; all retain gods and heroes and at least the patina of the magical.

Part of why I’m less concerned with historical accuracy owes to the fact Homer* wasn’t. It’s hard to have accuracy when the original text was all-over-the-place.

Homer composed a stunning piece of war fiction in terms of its impact on a soldier’s psyche. But it’s crap historical fiction. Let’s just put that out there at the start. Imagine putting Al Capone and 1920s gangsters in Elizabethan England, or maybe, Queen Elizabeth in 1920s Southside Chicago. That’s the time and cultural differential. He’s theoretically writing about events at the tail end of the Bronze Age (c. 1200-1100), but the social structure reflects the Early Iron Age as well as the Late Iron Age, with a few vestiges of the Bronze Age. But accuracy isn’t the *point*, for Homer.

Another point of clarification: the Iliad and Odyssey are about fictional people. There was no Agamemnon, Achilles, Priam, Hektor, or Helen. The Trojan War probably did happen—but not for the reasons or in the way the story relates. It’s a bit like Saving Private Ryan: WW II certainly happened, but Private Ryan is Everyman Lost.

Last, the basic plots of the Iliad and the Odyssey were not invented by Homer. These were well-known epic stories. Homer’s brilliance lay in what he did with them. Ergo, it’s more correct to speak of Homer as the composer of the Iliad and Odyssey, rather than the author/writer.

Therefore, what I’m looking for in modern retellings is what a MODERN author does with the same story. How does she or he use these familiar stories to talk about our present age…which is what Homer did himself, after all.

I’ve talked elsewhere about some issues I have with Miller’s Song of Achilles, but as is probably evident from what I said above, I have absolutely zero problems with her queering the tale. What I find more interesting is how her adaptation of Achilles and Patroklos as lovers speaks to our modern world and modern needs.

Any retelling of the Iliad today will run up against the brick wall of ancient values that were very different—and often rather repugnant—to modern readers. To ancient minds, Achilles was a HERO. Admirable. Worthy of emulation. To modern readers he’s, well, kind of a dick. And a butcher.

I’d submit that Homer meant him to be a jerk, too. Part of Homer’s lasting value is his ability to take a cultural hero and finesse him until he’s maybe not so hero-ish, but still comprehensible in his actions to listeners who had, themselves, experienced combat. Ergo, Homer’s Iliad still has something to say today to Vietnam Vets (as per Jonathan Shay’s brilliant Achilles in Vietnam). But most modern readers are not going to like the guy. He has a terrible temper, throws fits when thwarted, and is repeatedly described as “man-killing” like it’s a compliment.

So, as a modern author with a modern audience, how do you redeem him? (If you redeem him; not all authors choose to.)

Miller turned the Iliad into a love story, told from Patroklos's POV, which makes Achilles more likeable. He's painted by Patroklos’s adoration. In both Miller’s retelling and Homer’s original, Patroklos is depicted as empathic in a way modern readers can get behind, so he’s a good choice of point-of-view character. Yet although he comes off as your basic “nice guy,” in the original he is also a skilled warrior who kills a lot of people. Miller ignores this, making him a healer, not a fighter.

Like her casting of Thetis as bitchy, I have some issues with her decision to avoid dealing with the more brutal parts of Homer’s epic by eliding it. She’s buffed off the ugly rather than confronting it. It winds up feeling like a puff piece, alas, which I don't believe was her intention.

Why it does succeed owes not to the fact it’s a love story, but a queer love story. In antiquity, Achilles was a prince (as was Patroklos): the elite of the elite, the ruling class and conquering heroes. They were, in no way, an oppressed minority. A “subaltern” group.

Yet today, queer people are a subaltern population, although people in the queer community enjoy differing degrees of social acceptance. A black or brown trans woman experiences a great deal more oppression than a white gay guy. Yet public acceptance of queerness in any form is relatively recent, as in, something I’ve seen occur in my lifetime. And of course, now it’s being pushed back against.

So to have heroes who did occupy the ruling class and didn’t have to apologize for who they loved is important. If Achilles is a dick, well, he’s a gay dick (pun intended), and pretty, so we’ll slip him a pass.

Is that wrong? Homer doesn’t have a copyright on Achilles. Or Patroklos. Just as he used Achilles and Hektor and Priam to his own ends, so does Miller. Yet I am bothered by her ducking of the fundamental violence of the Iliad. Homer doesn’t, and it makes his the superior story. (Although topping Homer is rather a high bar.) Grief (and rage) make Achilles into a monster. Empathy redeems him…but it’s not empathy for Patroklos. In fact, his inability to empathize with Patroklos’s own grief gets his friend killed. Homer doesn’t sugar-coat that.

No, it’s empathy for the enemy—for Priam, when Priam evokes the grief Achilles’s own father will feel—that finally gets through to him. It re-humanizes him. He and Priam cry together.

See what Homer did there? That’s why the poem is still read c.2700 years after it was composed. On certain levels, it’s timeless. By contrast, Miller’s rendering is time/situation-dependent. It succeeds now. It wouldn’t have succeeded 50 years ago, if it had even got published, and I’m not sure it’ll be as relevant 50 years in the future. That’s not a condemnation. Sometimes books become important when they’re needed.

Yet, as I have issues with her ducking the story’s inherent violence, I also had issues with her handling of Thetis as one of only two prominent women in the novel. Again, there’s no copyright on Thetis, but in Greek myth, she’s not a cold bitch—in fact, she’s rather the opposite. So, while I think Miller’s queering of the Iliad had positive current social coin, her treatment of Thetis played into negative tropes about women (and mothers) that troubled me.

These are things I invite my students to wrestle with, when we talk about The Song of Achilles.

Btw, I sometimes see Miller grouped with Barker and Haynes and Atwood as “feminist” retellings of the Iliad. In no way is her book a feminist retelling. A queer retelling, but not a feminist one.

Let’s turn then to Barker. The very title of Barker’s book gives us a hint of what she wants to accomplish. The Silence of the Girls recasts the myth as the story of Briseis, Achilles’s war prize. Barker’s is one in a line of attempts to present the Iliad from a woman’s point of view, which goes back at least to Marion Zimmer Bradley’s 1987 Firebrand. Just as June Rachuy Brindel told Ariadne’s story (and Phaedra’s too) from a feminist perspective 40 years before Jennifer Saint (and was nominated for a Pulitzer). Another, more recent approach to this was Natalie Haynes’s A Thousand Ships, published just a year after Barker.

[A point: two books published a year apart do not owe to each other. It takes years to write, then publish a novel. But they may reflect current publishing perceptions of market interest.]

Barker makes a concerted effort to take a feminist look at the myth by centering Briseis as the narrator…but only for the first part. By part two, Achilles elbows his way in. Suddenly, it’s no longer Briseis’s story once she’s carted off to Agamemnon’s tent. It seems that Barker just couldn’t unhook entirely from centering Achilles, even if he’s more anti-hero.

We can consider this several ways. It’s possible that she didn’t want Achilles to be as simplistic as Briseis saw him, and therefore needed to get out of Briseis’s head in order to suggest more nuance. It’s also possible that she really does mean her title, The Silence of the Girls, and so silences the girl narrator when handed off to Agamemnon.

I have problems with both readings. First, the need to cast Achilles as more complex than Briseis wants to read him moves the needle away from the female/feminist perspective. Why should it be necessary to give Achilles depth if it’s Briseis’s story we’re telling? Unless she eventually comes to see depth in him…in which case, show us how she comes to that conclusion.

And if she really wanted to “silence” the girl when she became a slave, silence her THEN, not just when she moves residence. She’s no more a slave under Agamemnon than under Achilles. She might lack Patroklos’s support and semi-understanding, but her basic situation has not changed enough to justify a significant change in narrator.

To me, it just seems that Achilles sucked up all the air in the room, as he’s wont to do. He took over her story because Barker let him. It’s still a male-centric view.

This may have happened because Barker, like Miller, didn’t know enough history of the period to thoroughly reimagine the story she’s telling. In this respect, a little more historical accuracy—if not necessary—may have been helpful. How? By recentering the story not only on the female voice(s), but also on non-Mycenaean/Greek voices. Her opening was incredibly interesting, and could have had much more done with it. Marauding Greeks raze her town and take her captive. She comes from a satellite kingdom of the rich and powerful city of Wilusa (Troy), part of the Arzawa confederacy, itself a sometime-tribute group of the even more powerful Hittite Empire. The Mycenaeans are essentially pirates, hated by Hitties (and their allies?). It might have given Barker a two-pronged way to anchor her narrative more solidly: non-male AND non-Greek.

As noted, attempts at historical situating isn’t required. But Barker’s take ended up bogged down by the original Greek-centric view. She wanted to un-silence the girls, but unfortunately, by my reading, she only continued Achilles’s dominance.

So, I see both Miller’s and Barker’s attempts as not quite succeeding—which is interesting in itself. The books are hardly failures, or they wouldn’t have sold so many copies. And they do, in their own ways, take on Homer to resituate it for our era. But neither can quite get away from the historical value systems that make the Iliad problematic to modern readers.

Then we have Margaret Atwood, who takes us to school.

Folks, The Penelopiad is how you give voice to subaltern populations. For such a short book, it has wonderful layers.

First, this is not set in antiquity. Penelope tells her story from Hades, in the “now,” because she wants to correct Homer’s presentation of her (even though Homer’s presentation is overall rather favorable). The tone is modern and discursive. Some find it annoying, but she chooses it for a reason. While the book is not a comedy (unless black), it’s full of intentional, sarcastic humor.

Thousands of years have passed since the events of the Iliad and Odyssey. Penelope remains in Hades, not choosing to be reborn, unlike most of her contemporaries, including her husband…a nice nod to Plato’s Myth of Er where Odysseus is one of several souls who choose rebirth. I don’t know if Atwood is familiar with the story, but it’s Atwood, so it wouldn’t surprise me if she is. It’s an “Easter Egg” the average reader won’t get. Doesn’t matter. Atwood litters her novel with allusions to Greek myth, drama, and philosophy, as well as modern anthropology and Classics. None of it is necessary to follow her tale, but the more you know, the more you’re going to get from it. And the harder you’ll laugh (she spoofs Robert Graves’ White Goddess).

Most of the narrative is Penelope’s metafiction first-person account, but her chapters are broken up by a “chorus” of Penelope's twelve maids, actual figures from the Odyssey, mostly unnamed. Atwood uses them exactly as a Greek chorus in a traditional tragedy (which is what she’s writing). In Homer, the handmaids were traitorous little sluts, as ancient Greek men tended to see slaves, especially slave women. Atwood does something brilliant with them.

The Penelopiad lets women take over the narrative in a way Barker attempted but didn’t quite manage. If the men, Odysseus and Telemechus, are present, Atwood never lets them have a POV. Only Penelope or her maids narrate, and she sets those in tension. Like Briseis, Penelope is a member of the elite: a princess, then queen, however she presents herself in contrast to Helen. She’s a “poor little rich girl.” The twelve maids are manifestly not.

As the story unfolds, Atwood cleverly reminds us of something deeply embedded in Homer: these characters LIE. Odysseus is a magnificent liar, and Penelope lets us know it. “Bent-minded Odysseus” is the typical way he’s described by Homer, and it’s meant as a compliment. Even today, in Greece, being “clever” is better than being “smart.” Homer’s “bent-minded Penelope” is his match. He draws a sympathetic picture of her as Odysseus’s true partner, even if Odysseus entertains dalliances on the side. Of course, in that world, it was expected. Penelope is loyal, waiting at home…not unlike Penelope waiting in Hades here, never venturing out into new lives.

But we must remember: As Odysseus lies about his exploits and life, Penelope lies, too.

As we begin the book, the temptation for the reader—as Atwood intends—is to take Penelope’s account at face value. We may think we’re reading a novel that upends the narrative, centering female voices at last! But as the book continues, the chorus of maids presents us with a different tale, a different view. Then we reach the end and realize what Atwood has so cleverly done.

She truly decentered the narrative.

She’s not just telling Penelope’s story. She’s also telling what happened to the slave women, the twelve maids, who were hanged by Odysseus and Telemachus—in the original epic because they betrayed their mistress/Ithaca by consorting with the suitors. Here, Penelope, who’s just trying to survive, asks them to consort with the suitors to gain intelligence, and some are raped as a result. In the end, they’re executed along with their “lovers.” And Penelope didn’t step in to save them.

They’re expendable.

This is not just a Greek tragedy, but a horror story. Atwood reminds us that although Penelope may be less powerful than her husband, the King of Ithica, she is NOT truly disempowered. She is only half-subaltern. The maids, who are both women and slaves, are the truly disenfranchised. All they have in the world are their looks, and the protection of their mistress…which she doesn’t give.

So, they die.

Most people reading the Odyssey never think about the hanged maids—whether it was a just punishment. It happens in the background; they’re traitors like the suitors. But after reading Atwood, you’ll never read that poem again and overlook them.

Atwood’s novel is not romantic, not poetic, not inclined to have readers read and re-read it to get lost in the romance all over again (as with Miller’s). It’s deeply disturbing. And it’s meant to be.

Of these three novels, this is the one that will still be read, and resonate, fifty years down the road. This is the retelling of Homer that actually manages to unseat the accepted narrative and makes us re-examine the story from the real flip-side.

This one actually “unsilences” the (twelve) girls.

-------------------------

*I’m not going to touch the question of whether there was a “Homer,” and if so, was it one or two people, a he or a she, etc. There is a veritable tsunami of writing about who “Homer” may have been and the composition of these poems. Just be aware.

#Madeline Miller#Song of Achilles#Pat Barker#Silence of the Girls#Margaret Atwood#Penelopiad#modern takes on Homer#Homeric myth#Classics#Briseis#Achilles#Patroclus#Patroklos#Achilles in Vietnam#Ariadne#Penelope#Odysseus#subaltern voices#reception studies#reception of Homer#Queering Homer#Feminizing Homer#tagamemnon

199 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fathers remain opaque to their sons, he thought, largely because the sons find it so hard to believe that there’s anything in the father worth seeing. Until he’s dead, and it’s too late.

- Pat Barker, Regeneration

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Afternoon reading

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

I just finished The Silence of the Girls and feel like screaming and crying and sobbing in the metro. This book is so brutal and raw and it feels like being repeatedly punched in the guts.

#the silence of the girls#pat barker#the iliad#greek mythology#myth retelling#briseis#achilles#patroclus

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

"So to you straight folks / i say — Sure, i'll go / if you go too, / but i'm polite — / so — after you."

Read it here | Listen to the author read it here

Reblog for a larger sample size!

#closed polls#polls#poetry#poems#poetry polls#poets and writing#tumblr poetry#have you read this#pat barker#for the straight folks who don't mind gays but wish they weren't so blatant#lgbt#lgbt poems

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is an excerpt from the Regeneration Trilogy and it reminded me of something:

Just thought it was an interesting parallel.

#hozier#hozier eat your young#eat your young#unreal unearth#unreal unearth album#regeneration#the regeneration trilogy#regeneration trilogy#pat barker#regeneration pat barker#i hope hozier's read it that would be very cool#ww1 fiction#first world war fiction

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

Book ask! If you had to give a TEDTalk on a book you read this year, for better or worse, which would it be?

If it's not cheating to have a trilogy: Pat Barker's Life Class trilogy. In combination with Alice Winn's In Memoriam (and other books I read in previous years), focusing on Toby's Room could be a really interesting springboard to talk about the World War I novels that deal with queer stories and themes. Or I could talk about the way in which Barker tries to confront and talk about how we represent and depict trauma and what happens when there is no catharsis after representation. Or the motif of facial disfigurement. I also really liked the idea behind Noonday, where those who had suffered but survived WWI come to confront the failure of "the war to end all wars" with the arrival of WWII, even if I felt Barker didn't quite nail it. Her novels are just so rich and complex, I could talk about them forever.

#oldshrewsburyian#asks#text posts#pat barker#oh pat barker we're really in it now#(for worse would be a r torre's the old lie but the less said about that infuriating novel the better)

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

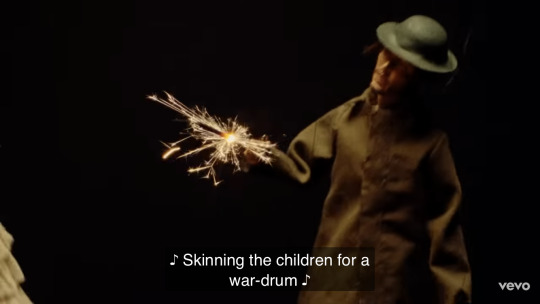

Title: The Women of Troy | Author: Pat Barker | Publisher: Doubleday (2021)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

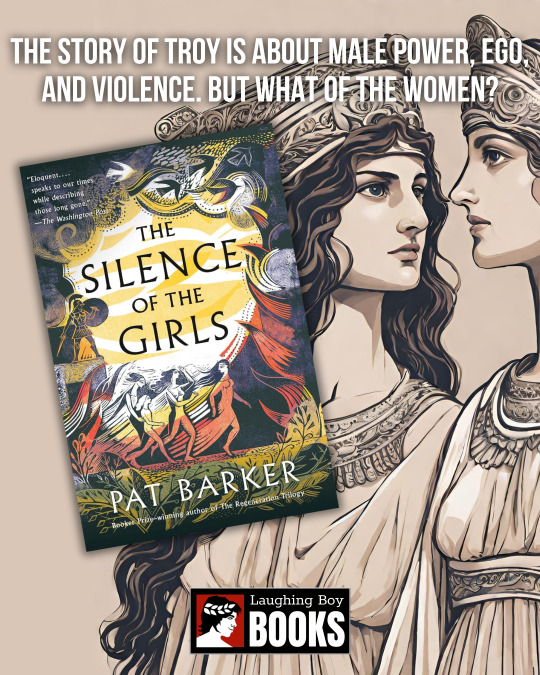

Here is the story of the Iliad as we've never heard it before: in the words of Briseis, Trojan queen and captive of Achilles. Given only a few words in Homer's epic and erased mainly by history, she is a pivotal figure in the Trojan War. In these pages, she comes entirely to life: wry, watchful, forging connections among her fellow female prisoners even as she is caught between Greece's two most powerful warriors.

https://bookshop.org/a/95413/9780525564102

#pat barker#the silence of the girls#trojan war#trojan women#ancient greece#ancient greek#greek myths#classical mythology#ancient greek mythology#the illiad

2 notes

·

View notes