#modern takes on Homer

Note

Dear Professor, elsewhere you mentioned teaching Miller, Barker and Atwood and I was wondering if you could expand a little on your thoughts on their respective retellings.

QUEERING AND FEMINIZING HOMER: MILLER, BARKER & ATWOOD

For my “Ancient Greece in Modern Historical Fiction” course, I assigned three texts that all dealt with the Homeric poems, in order to examine how ancient myth can be reappropriated for modern audiences. These were Madeline Miller’s The Song of Achilles, Pat Barker’s The Silence of the Girls, and Margaret Atwood’s The Penelopiad.

There are a lot, and I do mean a lot of retellings of the Iliad or Odyssey. Some, maybe most, do so in a straightforward way, treating the myth like an historical novel. They may try to resituate it in another head, like Helen’s, or Hektor’s, or even Paris’s. But they don’t, otherwise, change much. If anything, they attempt to eliminate the fantastical elements (like gods) and play the story as if it really happened.

Yet the nature of myths makes them different from historical fiction. The latter, for me, has a much higher bar for detail accuracy. A myth begins as fiction, so while I do appreciate various renditions attempting historical accuracy, I don’t see it as essential to a good retelling. And the three novels I chose mostly don’t track in that direction; all retain gods and heroes and at least the patina of the magical.

Part of why I’m less concerned with historical accuracy owes to the fact Homer* wasn’t. It’s hard to have accuracy when the original text was all-over-the-place.

Homer composed a stunning piece of war fiction in terms of its impact on a soldier’s psyche. But it’s crap historical fiction. Let’s just put that out there at the start. Imagine putting Al Capone and 1920s gangsters in Elizabethan England, or maybe, Queen Elizabeth in 1920s Southside Chicago. That’s the time and cultural differential. He’s theoretically writing about events at the tail end of the Bronze Age (c. 1200-1100), but the social structure reflects the Early Iron Age as well as the Late Iron Age, with a few vestiges of the Bronze Age. But accuracy isn’t the *point*, for Homer.

Another point of clarification: the Iliad and Odyssey are about fictional people. There was no Agamemnon, Achilles, Priam, Hektor, or Helen. The Trojan War probably did happen—but not for the reasons or in the way the story relates. It’s a bit like Saving Private Ryan: WW II certainly happened, but Private Ryan is Everyman Lost.

Last, the basic plots of the Iliad and the Odyssey were not invented by Homer. These were well-known epic stories. Homer’s brilliance lay in what he did with them. Ergo, it’s more correct to speak of Homer as the composer of the Iliad and Odyssey, rather than the author/writer.

Therefore, what I’m looking for in modern retellings is what a MODERN author does with the same story. How does she or he use these familiar stories to talk about our present age…which is what Homer did himself, after all.

I’ve talked elsewhere about some issues I have with Miller’s Song of Achilles, but as is probably evident from what I said above, I have absolutely zero problems with her queering the tale. What I find more interesting is how her adaptation of Achilles and Patroklos as lovers speaks to our modern world and modern needs.

Any retelling of the Iliad today will run up against the brick wall of ancient values that were very different—and often rather repugnant—to modern readers. To ancient minds, Achilles was a HERO. Admirable. Worthy of emulation. To modern readers he’s, well, kind of a dick. And a butcher.

I’d submit that Homer meant him to be a jerk, too. Part of Homer’s lasting value is his ability to take a cultural hero and finesse him until he’s maybe not so hero-ish, but still comprehensible in his actions to listeners who had, themselves, experienced combat. Ergo, Homer’s Iliad still has something to say today to Vietnam Vets (as per Jonathan Shay’s brilliant Achilles in Vietnam). But most modern readers are not going to like the guy. He has a terrible temper, throws fits when thwarted, and is repeatedly described as “man-killing” like it’s a compliment.

So, as a modern author with a modern audience, how do you redeem him? (If you redeem him; not all authors choose to.)

Miller turned the Iliad into a love story, told from Patroklos's POV, which makes Achilles more likeable. He's painted by Patroklos’s adoration. In both Miller’s retelling and Homer’s original, Patroklos is depicted as empathic in a way modern readers can get behind, so he’s a good choice of point-of-view character. Yet although he comes off as your basic “nice guy,” in the original he is also a skilled warrior who kills a lot of people. Miller ignores this, making him a healer, not a fighter.

Like her casting of Thetis as bitchy, I have some issues with her decision to avoid dealing with the more brutal parts of Homer’s epic by eliding it. She’s buffed off the ugly rather than confronting it. It winds up feeling like a puff piece, alas, which I don't believe was her intention.

Why it does succeed owes not to the fact it’s a love story, but a queer love story. In antiquity, Achilles was a prince (as was Patroklos): the elite of the elite, the ruling class and conquering heroes. They were, in no way, an oppressed minority. A “subaltern” group.

Yet today, queer people are a subaltern population, although people in the queer community enjoy differing degrees of social acceptance. A black or brown trans woman experiences a great deal more oppression than a white gay guy. Yet public acceptance of queerness in any form is relatively recent, as in, something I’ve seen occur in my lifetime. And of course, now it’s being pushed back against.

So to have heroes who did occupy the ruling class and didn’t have to apologize for who they loved is important. If Achilles is a dick, well, he’s a gay dick (pun intended), and pretty, so we’ll slip him a pass.

Is that wrong? Homer doesn’t have a copyright on Achilles. Or Patroklos. Just as he used Achilles and Hektor and Priam to his own ends, so does Miller. Yet I am bothered by her ducking of the fundamental violence of the Iliad. Homer doesn’t, and it makes his the superior story. (Although topping Homer is rather a high bar.) Grief (and rage) make Achilles into a monster. Empathy redeems him…but it’s not empathy for Patroklos. In fact, his inability to empathize with Patroklos’s own grief gets his friend killed. Homer doesn’t sugar-coat that.

No, it’s empathy for the enemy—for Priam, when Priam evokes the grief Achilles’s own father will feel—that finally gets through to him. It re-humanizes him. He and Priam cry together.

See what Homer did there? That’s why the poem is still read c.2700 years after it was composed. On certain levels, it’s timeless. By contrast, Miller’s rendering is time/situation-dependent. It succeeds now. It wouldn’t have succeeded 50 years ago, if it had even got published, and I’m not sure it’ll be as relevant 50 years in the future. That’s not a condemnation. Sometimes books become important when they’re needed.

Yet, as I have issues with her ducking the story’s inherent violence, I also had issues with her handling of Thetis as one of only two prominent women in the novel. Again, there’s no copyright on Thetis, but in Greek myth, she’s not a cold bitch—in fact, she’s rather the opposite. So, while I think Miller’s queering of the Iliad had positive current social coin, her treatment of Thetis played into negative tropes about women (and mothers) that troubled me.

These are things I invite my students to wrestle with, when we talk about The Song of Achilles.

Btw, I sometimes see Miller grouped with Barker and Haynes and Atwood as “feminist” retellings of the Iliad. In no way is her book a feminist retelling. A queer retelling, but not a feminist one.

Let’s turn then to Barker. The very title of Barker’s book gives us a hint of what she wants to accomplish. The Silence of the Girls recasts the myth as the story of Briseis, Achilles’s war prize. Barker’s is one in a line of attempts to present the Iliad from a woman’s point of view, which goes back at least to Marion Zimmer Bradley’s 1987 Firebrand. Just as June Rachuy Brindel told Ariadne’s story (and Phaedra’s too) from a feminist perspective 40 years before Jennifer Saint (and was nominated for a Pulitzer). Another, more recent approach to this was Natalie Haynes’s A Thousand Ships, published just a year after Barker.

[A point: two books published a year apart do not owe to each other. It takes years to write, then publish a novel. But they may reflect current publishing perceptions of market interest.]

Barker makes a concerted effort to take a feminist look at the myth by centering Briseis as the narrator…but only for the first part. By part two, Achilles elbows his way in. Suddenly, it’s no longer Briseis’s story once she’s carted off to Agamemnon’s tent. It seems that Barker just couldn’t unhook entirely from centering Achilles, even if he’s more anti-hero.

We can consider this several ways. It’s possible that she didn’t want Achilles to be as simplistic as Briseis saw him, and therefore needed to get out of Briseis’s head in order to suggest more nuance. It’s also possible that she really does mean her title, The Silence of the Girls, and so silences the girl narrator when handed off to Agamemnon.

I have problems with both readings. First, the need to cast Achilles as more complex than Briseis wants to read him moves the needle away from the female/feminist perspective. Why should it be necessary to give Achilles depth if it’s Briseis’s story we’re telling? Unless she eventually comes to see depth in him…in which case, show us how she comes to that conclusion.

And if she really wanted to “silence” the girl when she became a slave, silence her THEN, not just when she moves residence. She’s no more a slave under Agamemnon than under Achilles. She might lack Patroklos’s support and semi-understanding, but her basic situation has not changed enough to justify a significant change in narrator.

To me, it just seems that Achilles sucked up all the air in the room, as he’s wont to do. He took over her story because Barker let him. It’s still a male-centric view.

This may have happened because Barker, like Miller, didn’t know enough history of the period to thoroughly reimagine the story she’s telling. In this respect, a little more historical accuracy—if not necessary—may have been helpful. How? By recentering the story not only on the female voice(s), but also on non-Mycenaean/Greek voices. Her opening was incredibly interesting, and could have had much more done with it. Marauding Greeks raze her town and take her captive. She comes from a satellite kingdom of the rich and powerful city of Wilusa (Troy), part of the Arzawa confederacy, itself a sometime-tribute group of the even more powerful Hittite Empire. The Mycenaeans are essentially pirates, hated by Hitties (and their allies?). It might have given Barker a two-pronged way to anchor her narrative more solidly: non-male AND non-Greek.

As noted, attempts at historical situating isn’t required. But Barker’s take ended up bogged down by the original Greek-centric view. She wanted to un-silence the girls, but unfortunately, by my reading, she only continued Achilles’s dominance.

So, I see both Miller’s and Barker’s attempts as not quite succeeding—which is interesting in itself. The books are hardly failures, or they wouldn’t have sold so many copies. And they do, in their own ways, take on Homer to resituate it for our era. But neither can quite get away from the historical value systems that make the Iliad problematic to modern readers.

Then we have Margaret Atwood, who takes us to school.

Folks, The Penelopiad is how you give voice to subaltern populations. For such a short book, it has wonderful layers.

First, this is not set in antiquity. Penelope tells her story from Hades, in the “now,” because she wants to correct Homer’s presentation of her (even though Homer’s presentation is overall rather favorable). The tone is modern and discursive. Some find it annoying, but she chooses it for a reason. While the book is not a comedy (unless black), it’s full of intentional, sarcastic humor.

Thousands of years have passed since the events of the Iliad and Odyssey. Penelope remains in Hades, not choosing to be reborn, unlike most of her contemporaries, including her husband…a nice nod to Plato’s Myth of Er where Odysseus is one of several souls who choose rebirth. I don’t know if Atwood is familiar with the story, but it’s Atwood, so it wouldn’t surprise me if she is. It’s an “Easter Egg” the average reader won’t get. Doesn’t matter. Atwood litters her novel with allusions to Greek myth, drama, and philosophy, as well as modern anthropology and Classics. None of it is necessary to follow her tale, but the more you know, the more you’re going to get from it. And the harder you’ll laugh (she spoofs Robert Graves’ White Goddess).

Most of the narrative is Penelope’s metafiction first-person account, but her chapters are broken up by a “chorus” of Penelope's twelve maids, actual figures from the Odyssey, mostly unnamed. Atwood uses them exactly as a Greek chorus in a traditional tragedy (which is what she’s writing). In Homer, the handmaids were traitorous little sluts, as ancient Greek men tended to see slaves, especially slave women. Atwood does something brilliant with them.

The Penelopiad lets women take over the narrative in a way Barker attempted but didn’t quite manage. If the men, Odysseus and Telemechus, are present, Atwood never lets them have a POV. Only Penelope or her maids narrate, and she sets those in tension. Like Briseis, Penelope is a member of the elite: a princess, then queen, however she presents herself in contrast to Helen. She’s a “poor little rich girl.” The twelve maids are manifestly not.

As the story unfolds, Atwood cleverly reminds us of something deeply embedded in Homer: these characters LIE. Odysseus is a magnificent liar, and Penelope lets us know it. “Bent-minded Odysseus” is the typical way he’s described by Homer, and it’s meant as a compliment. Even today, in Greece, being “clever” is better than being “smart.” Homer’s “bent-minded Penelope” is his match. He draws a sympathetic picture of her as Odysseus’s true partner, even if Odysseus entertains dalliances on the side. Of course, in that world, it was expected. Penelope is loyal, waiting at home…not unlike Penelope waiting in Hades here, never venturing out into new lives.

But we must remember: As Odysseus lies about his exploits and life, Penelope lies, too.

As we begin the book, the temptation for the reader—as Atwood intends—is to take Penelope’s account at face value. We may think we’re reading a novel that upends the narrative, centering female voices at last! But as the book continues, the chorus of maids presents us with a different tale, a different view. Then we reach the end and realize what Atwood has so cleverly done.

She truly decentered the narrative.

She’s not just telling Penelope’s story. She’s also telling what happened to the slave women, the twelve maids, who were hanged by Odysseus and Telemachus—in the original epic because they betrayed their mistress/Ithaca by consorting with the suitors. Here, Penelope, who’s just trying to survive, asks them to consort with the suitors to gain intelligence, and some are raped as a result. In the end, they’re executed along with their “lovers.” And Penelope didn’t step in to save them.

They’re expendable.

This is not just a Greek tragedy, but a horror story. Atwood reminds us that although Penelope may be less powerful than her husband, the King of Ithica, she is NOT truly disempowered. She is only half-subaltern. The maids, who are both women and slaves, are the truly disenfranchised. All they have in the world are their looks, and the protection of their mistress…which she doesn’t give.

So, they die.

Most people reading the Odyssey never think about the hanged maids—whether it was a just punishment. It happens in the background; they’re traitors like the suitors. But after reading Atwood, you’ll never read that poem again and overlook them.

Atwood’s novel is not romantic, not poetic, not inclined to have readers read and re-read it to get lost in the romance all over again (as with Miller’s). It’s deeply disturbing. And it’s meant to be.

Of these three novels, this is the one that will still be read, and resonate, fifty years down the road. This is the retelling of Homer that actually manages to unseat the accepted narrative and makes us re-examine the story from the real flip-side.

This one actually “unsilences” the (twelve) girls.

-------------------------

*I’m not going to touch the question of whether there was a “Homer,” and if so, was it one or two people, a he or a she, etc. There is a veritable tsunami of writing about who “Homer” may have been and the composition of these poems. Just be aware.

#Madeline Miller#Song of Achilles#Pat Barker#Silence of the Girls#Margaret Atwood#Penelopiad#modern takes on Homer#Homeric myth#Classics#Briseis#Achilles#Patroclus#Patroklos#Achilles in Vietnam#Ariadne#Penelope#Odysseus#subaltern voices#reception studies#reception of Homer#Queering Homer#Feminizing Homer#tagamemnon

198 notes

·

View notes

Text

I misread this spelling of Phoebus as closer to the Greek word for fear (φοβος) and the passage was all about Apollo doing some divine murder

so anyway hot take: Apollo is fear

#is this me overanalysing something that isnt meant to be analysed? yes#these are my thoughts#take them or leave them#the illiad#apollo#homer#literature#i wonder if the ancient greek word for fear is different from the modern one#i cant read ancient greek for shit bc my brain only knows modern

0 notes

Text

Hellenic Polytheism or Hellenismos is the traditional, polytheistic (multiple gods) religious belief system of Ancient Greece. Modern people who believe in pre-Christian and polytheistic belief systems often refer to themselves as pagans. Let’s look at some of the general practices of typical Hellenic worship.

Hellenic Polytheists use altars or shrines to worship specific Gods within the Greek Pantheon. For example, an altar for Apollo may contain an image or sculpture bust of the god, as well as a side table, called a trapezōmata, which holds offerings of incense and flowers or food and drink such as wine, honey, milk, or olive oil. Another tripod incense holder was called a Thymiateria.

Before engaging in a ceremony, the practitioner will employ purification methods with lustral water (ritually cleansed). They may recite hymns or prayers in honor of the god, using the Homeric hymns for example. The practitioner may use a divination practice to seek guidance or gain insight from a god through methods like casting lots, reading signs from nature, oracle prophecies, and dream interpretations. In their ceremonies, ancient Greeks would perform rites in respect to their Ta Patria, (ancestral homeland heritage), and they would take pride in their reverence with Hos Kallista, or the highest level of beauty.

Hellenic Polytheism follows annual calendar festivals commemorating Gods or famous mythological events such as the Panathenaia in Athens (commemorating Athena), the Anthesteria and City Dionysia; (festivals celebrating Dionysus) The Olympics (a physical competition in honor of Zeus) and the Thargelia, (dedicated to Apollo and Artemis), and the Thesmophoria, (a festival exclusive to women in honor of Demeter), among many others.

Want to own my Illustrated Greek myth book jam packed with over 130 illustrations like this? Support my kickstarter for my book "lockett Illustrated: Greek Gods and Heroes" coming in October.You can also sign up for my free email newsletter. please check my LINKTREE:

#pagan#hellenism#greek mythology#tagamemnon#mythology tag#percyjackson#dark academia#greek#greekmyths#classical literature#percy jackon and the olympians#pjo#homer#iliad#classics#mythologyart#art#artists on tumblr#odyssey#literature#ancientworld#ancienthistory#ancient civilizations#ancientgreece#olympians#greekgods#zeus#hesiod

527 notes

·

View notes

Note

good morning Neil Gaiman!

I trust you're aware of Jediism and other such phenomenons in which people take modern fiction and declare its lore and base philosophies as religion. This is almost no different from what the Greeks did with Homer and the scrolls that made up the Bible, all those years ago. However, my question is how would you feel if a group of people decided to start praying to Lord Morpheus, or create a tabernacle of Desire or calling on Death (specifically the one who watches Mary Poppins and looks strangely like Siouxsie Sioux). as these are your creations, how would you feel if people took The Sandman as truth and declared it their religion?

Thank you!

I'd point them to the bits in the Sandman that explain that the Endless are not Gods and should not be worshipped, and that setting up religions around them is very dangerous indeed.

733 notes

·

View notes

Text

Homeric moment of empathy towards women

Once Patroclus has been grieved by Achilles and the rest of the soldiers, his body is carried to Achilles' tent, to be grieved by the women slaves there. Meanwhile, Achilles and Agamemnon reconcile, Agamemnon vows he has not touched Briseis and sends her back to Achilles. When Briseis enters the tent, despite technically belonging to the opposite side, she spontaneously weeps for him. She reminisces that Patroclus consoled her when Achilles killed her kin and was promising to her that he would convince Achilles to take her back to Phthia with him and marry her properly. She calls Patroclus "sweet".

This is a very informative excerpt for the early Archaic period or, even, the late Bronze Age if it's accurate to it. What would seem outrageous nowadays, seems to effectively console Briseis and give her hope. It would be crazy to consider marrying the killer of your kin with hope or receive it as consolation. However, we should remember the disadvantageous position of women at the time. Briseis had no family anymore, thanks to Achilles, and not a husband anymore, also thanks to Achilles. If Achilles left her behind before leaving for Greece, there were most likely only two possibilities for her: death or prostitution. This means that despite essentially being her enemy, Briseis depended on Achilles for her well-being and survival. Therefore it really made a difference that Patroclus promised her to talk Achilles into marrying her - thus improving her status drastically to being a queen consort of his.

But I found what follows even more interesting:

Translation in English:

"So she said, weeping, then the women were sorrowful, supposedly for Patroclus, but actually for their own woes."

We see how Homer (or the ancient rhapsodoi - bards anyway) acknowledges the face women are forced to put on in front of the repressive society and he acknowledges how they use this as an opportunity to freely release their own pain, contemplate their own problems, while justifiedly lacking in genuine regard for the soldiers they have to serve.

BTW irrelevant but I have said before how I prefer as faithful translations as possible, in all languages but even more so when it comes to interpretation of Ancient Greek into Modern, so here's a closer one by me, seperated with colours to make it easier for you to follow through:

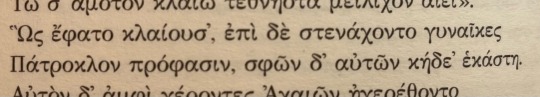

Ancient Greek:

Ὣς ἔφατο κλαίουσ᾽, ἐπὶ δὲ στενάχοντο γυναῖκες, Πάτροκλον πρόφασιν, σφῶν δ᾽ αὐτῶν κήδε᾽ ἑκάστη.

Modern Greek:

Ούτως είπε κλαίουσ', έπειτα δε, στεναχωριόνταν οι γυναίκες, με τον Πάτροκλο πρόφαση, γι' αυτών τους κηδευμένους έκαστη.

#greece#iliad#homeric epics#homer#patroclus#greek#greek language#ancient greek#modern greek#langblr#language stuff#linguistics

197 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey do you have any literature recommendations for people who want to broaden their knowledge on the classics and Greek/Roman myths without taking university courses?

So like for people (such as myself) who have read Bullfinch's Myths of Greece and Rome and Edith Hamilton's Mythology: Timeless Tales of Gods and Heroes but want to deepen their knowledge and maybe go to intermediate level type stuff. Or whatever the level above the mentioned literature is.

Well those two books are quite old and skip over quite a few things. Both are very important to our culture, historically, but I'd recommend reading through some more modern popular retellings like Stephen Fry's Mythos series if you're looking for pure entertainment and a dummy's guide to Greek myths.

The Penguin Dictionary of Classical Mythology is a useful reference book if you have difficulty keeping track of all these names and whatnot. It's just a reference book but you know. Having a reference book handy is quite useful. I personally prefer reference books when it comes to checking stuff when I'm doing mythology things anyways. They're generally more organized than the internet.

If you're looking for entertaining retellings of less popular myths, I'd actually recommend going to videos and podcasts for that. YouTubers like MonarchsFactory, Overly Sarcastic Productions, Jake Doubleyoo, and Mythology & Fiction Explained are all people who do a lot of research themselves on the myths they retell and I would recommend all of them to basically anybody. As far as podcasts go, Mythology & Fiction Explained has a podcast version and Let's Talk About Myths, Baby! is a very informative podcast that talks about sources for the myths and has interviews with experts on the subjects. It's also a podcast that is specifically Greco-Roman based.

As far as doing slightly more in-depth research, I cannot recommend theoi.com enough. I really can't. It has overviews of the most common myths, it has pages about god and hero cults, it cites it's sources and has an online library of translated texts. It's just really good. Go clicking around it for a while. It's a lot of fun if you're into that sort of thing.

As far as primary sources for myths go, there's a few places you could start. The Iliad, perhaps. The most recent English translation is by Caroline Alexander but I personally prefer Stanley Lombardo's translation. The Odyssey is a more accessible read in my opinion if you're not used to reading epic poetry. Emily Wilson's translation is especially accessible, written in iambic pentameter and generally replicating Homer's simple conversational language.

The third traditional entrance into the epic cycle of the surviving literature is the Aeneid. The newest translation of that is by Shadi Bartsch, which is pretty good, but it reads more like prose than poetry. Would still highly recommend it though. Robert Fitzgerald's translation is also good.

If you wanna get fancy you can read the Post-Homerica which attempts to bridge the gap between the Iliad and the Odyssey. It's not often read but it's one of the latest pagan sources we have from people who still practiced ancient Greek religion.

If you want a collection of short stories from ancient times, Ovid's your guy. Metamorphosis is specifically Roman and specifically Ovid's fanfiction, but it's also a valid primary resource and Ovid generally views women as people. What a concept!

Though I think the absolute best overview from ancient times itself is The Library aka Biblioteca by pseudo-apollodorus. Doesn't matter what translation you get. The prose is simple to the point where it's difficult to screw it up. Not artistic at all. It is, quite simply, a guy from ancient times trying to write down the mythological history of the world as he knew it. It has a bunch of summaries of myths in it, and most modern printings also have a table of contents so you can essentially use it as a reference book or a cheat sheet. I love it.

The Homeric Hymns weren't actually written by Homer but that's what they're called anyways. They're a lovely bit of poetry because, well, they were originally hymns. They've got some of the earliest full tellings of the Hades and Persephone story and the birth of Hermes in them. They also provide an insight into how ancient people who were most devoted to these gods viewed them. Go read the Homeric Hymns. They're lovely. You can buy the Michael Crudden translation or you can read a public domain translation online. I don't care. Just read them.

If you're into tedious lists, the next place I'd recommend you go after you read all the fun stuff is Hesiod's Theogony. Hesiod, the red pill douchebag of the ancient world, decided he was gonna write down the genealogy of all the Greek gods. That means lists. I'm not exaggerating. Be prepared for a lot of lists. But this work also has the earliest and one of the most complete versions of the story of Pandora, the creation of humans, and the most popular version of the Greek creation myth. So, it's very useful. If you can take all the lists.

The Argonautica aka the voyage of the argo by Apollonius of Rhodes, is also here. That is also a thing you can read. About the golden fleece and whatnot. And Jason. You know Jason. We all hate Jason.

Greek theatre also provides a good overview of specific myths. The three theben plays, Medea, the Bacche, etc. We've only got thirty-something surviving plays in their entirety so like... look up the list. Find one that looks interesting. Read it. Find a performance of it online, maybe. They're good.

If you want to dive into the mythology as a religion that was practiced, Greek Religion by Walter Burkurt and Ancient Greek Cults: A Guide by Jennifer Larson are pretty good books on the topic and often used as textbooks in college courses.

If you wanna get meta and get a feel for what the general public today thinks about Greek myths and what the average person that's sort of knowledgeable about Greek myths knows, the books you already mentioned are good. That's what people usually read. In addition to those, most people's intro to Greek myths generally involves The Complete World of Greek Mythology by Richard Buxton, D’Aulaires’ Book of Greek Myths by Ingri and Edgar Parin d’Aulaire, or The Percy Jackson series.

I've been flipping through the big stacks of mythology books I keep on my table trying to remember if I've forgotten anything but I don't think I have so, yeah. Hope this helps. There's no correct starting point here. Once you get started there's a nearly endless void of complications and scholarship you can fall down that you'll never reach the bottom of. This post is basically just a guide to the tip of the iceberg.

#mythology#greek mythology#roman mythology#reference#roman said a thing#classical mythology#classics#classics reference#mythology for beginners#mythology reference#greco-roman

383 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Look, I would like to go back once again to simple everyday life. Each man has a specific consciousness, a specific memory of his childhood. If you consider your own childhood, you will find certain quite distinct types of experience. There are certain things which appear to you today as purely anecdotal, as it were, which have no connection with your present mental and moral existence. On the other hand you will find that you did and said in your childhood certain things which foreshadow in nuce your entire present ego. We must consider the past ontologically and not in the sense of epistemology. If I consider the past epistemologically, then something from the past is simply past.

Ontologically however the past is not always simply past, but exerts an influence on the present not of course the entire past, but parts of it and not always the same parts. I would like to take you back once more to your own development: in your development different aspects of your childhood certainly played different roles at different times. This whole process of conservation in art, which I see as a memory of the past of humanity, is thus a very complicated one. I need only recall that by the end of antiquity Homer was almost forgotten, and until the beginning of the modern era was completely displaced by Virgil; it was in Virgil that the men of the Middle Ages discovered their childhood. Bourgeois culture had to arise-the English critics, for example, who used to play Homer off against Virgil, or Vico in the eighteenth century in order for humanity to link up with Homer as its own past. A similar development took place with Shakespeare. There is thus a fluctuation in what is considered as living world literature or world art; consider for example how such an important art historian as Buckhard completely rejected mannerism and baroque, and what a renaissance of mannerism there is today.

It should be evident to anyone that this memory is itself a historic process, and that if I consider memory and the past, I am constrained precisely on that account to conceive these as ontological moments of the living development of humanity, not as an epistemological articulation of time into past, present and future -which can have its meaning in certain special scientific connections. It is not true, however, as Benjamin believed, that something from the past, if it becomes present, springs up out of the past. My greatest childhood experience was when, at nine years old, I read a Hungarian prose translation of the lad; the fate of Hector, i.e. the fact that the man who suffered a defeat was in the right and was the better hero, was determinant for my entire later development. This is evidently fixed in Homer, and if it were not so fixed, it could not have this effect. However it is equally clear that not everyone read the lliad in this way.

Just think of the difference between Dante's conception of Brutus and that of the Renaissance, and you will see the distinction I am making. Here is a great process, a continuous process, from which every epoch extracts that which serves its own ends.”

Georg Lukacs, Conversations with Lukacs

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lore Olympus ch. 253 critique

I think this time I'll start out with the major critiques and then move to the minor ones.

The Cause of Winter

So. Persephone is the cause of winter.

Can't wait to see where Rachel tries to take this one /s.

But for real though, I can't possibly imagine how this is going to work in this "modern feminist" retelling. In the original Homeric Hymn to Demeter, Demeter causes an eternal-like winter/famine in order to get her daughter back from Hades since he refused to return her, and since Zeus' solution to the situation was basically "tough tits". It was this huge feminist act to show that Demeter not only loved her daughter but was willing to burn the world to the ground in order to see her return.

And that's what galls me about Lore Olympus. The Homeric Hymn to Demeter was already considered to be pretty feminist for the time it was written. Demeter was able to subvert the traditional idea that once a daughter was married, she could never return home. She challenged this idea, challenged Zeus, something others wouldn't have gotten away with unpunished. This was something mothers in Ancient Greece could not achieve since they had no power or say in their daughter's marriage. Even though Demeter did not fully win in the end, with Persephone being bound to Hades for 6 months out of the year, etc., it gave ancient women hope that they, too, could one day see their daughters again.

In my opinion, there is no way that the action of Persephone causing winter can be more feminist than what Demeter did in the original story.

The Payphone

This one is a tiny one. Pretty much insignificant. But it just annoyed the shit out of me.

Really? A payphone? In the mortal realm? In a time where the modern technology we have today does not exist?

Additionally, there is no way Eros and Psyche could've gotten back to Olympus that fast because if they had, they might as well have warned Zeus in person. Why couldn't they have contacted Zeus through Iris? She is a messenger of the gods after all. Besides the very stupid plot that Apollo, of all people, would want to try and overthrow Zeus, this whole arc feels super rushed so much in fact that they have a frickin payphone where it should not exist.

Welp. See y'all in my next post. Hope everyone had a happy turkey day

#anti lore olympus#anti lo persephone#lo critical#unpopular lo#unpopular lore olympus#lo hate#anti lo#lore olympus critical#lo critic#lo criticism#lore olympus criticism

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

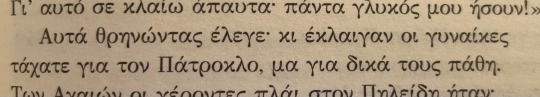

Ancient Roman Mosaic Reveals Women Wore Bikini

It is believed that the bikini was a 20th century invention, but an ancient mosaic reveals women in Rome wore it while playing sports.

The Villa Romana del Casale, located in Sicily, dates back to the early fourth century AD. Among the ruins, archeologists have discovered one of the largest collections of ancient Roman mosaics.

All of them are surprisingly well preserved. One of the rooms of the villa is called Sala delle Dieci Ragazze, which can be translated as “Room of the Ten Girls” – based on the number of those depicted in the floor mosaic.

Eight of them wear what in the modern world would be called a two-piece bikini, another woman wears a yellow translucent dress, while the image of the only one figure has not survived to this day.

The bottom of this set of clothing looks like a terracotta-colored band made of fabric or leather, similar to men’s loincloths. As for the top, it is reminiscent of a modern strapless breastband. Such chest harnesses also have their own history and have been known since the times of Ancient Greece. It is believed that most often the material for this was linen. This piece of clothing was intended for women leading an active lifestyle and partaking in physical exercise.

Thus, it can be assumed that in ancient times such a bikini was not used for swimming, but rather for sports. This is exactly what all the women depicted in the mosaic are doing. Some of them run, and others throw a discus or hold weights in their hands.

Two women are playing with a ball together. Researchers speculate that this could be some kind of early form of volleyball. In general, ball games are considered one of the most ancient. Their mentions can be found in Homer’s Odyssey. One of the girls, standing in the center, holds a palm branch in one hand and is about to place a victory crown on her head – probably a reward for the best performance. All the women look athletic and have noticeable muscle outlines on their arms and legs.

When it comes to sports, women in ancient Rome were permitted to practice physical forms of exercise, but they faced certain restrictions within a patriarchal society. They were not allowed to take part in competitions with men, and public female nudity was frowned upon. Therefore, a kind of prototype of the modern bikini made it possible to play sports without much inconvenience.

By Maria Rybachuk.

#Ancient Roman Mosaic Reveals Women Wore Bikini#Roman Bikini Girls#Room of the Ten Girls#mosaic#roman mosaic#The Villa Romana del Casale#sicily italy#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#roman history#roman empire#roman art

115 notes

·

View notes

Note

I’ve seen the word Khaire used a lot in the Hellenic Polytheism community, and I was wondering what it meant. From what I came across, it seems to be a greeting of some sort, but I don’t know the context it is used in.

Hope you are feeling better!

Hey there, thanks for the ask!

Khaire is an ancient Greek greeting, yes. It's a friendly greeting that means something along the lines of "be of good cheer" or "welcome" or "be well". It was typically used to greet others kindly and politely and was so common that even Homer used it. From my knowledge, it comes from the verb, Χαίρω, meaning to rejoice at or take pleasure in something.

It's pretty much a kind greeting that was meant to express your enthusiasm about seeing someone. It was typically used in a positive, lighthearted context, but in modern times, it appears to be used more formally as Χαίρετε rather than Χαίρε (I obviously could be wrong about that; I'm not a linguistics expert by any means, and when I went to Greece myself, I heard literally no one using that word lol).

Any linguistics, classics, or Greek-speaking people are welcome to correct me; I found all this through various sources online (some I do not trust, tbh), and I'd rather be correct than right. 👌

I hope this clears up any confusion for you, and thank you for the well wishes! Take care, and have a good night/day. 🧡

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Odyssey - an opinion on Odysseus

Tw: reference to sexual assault, coercision, rape in abstract terms as themes.

Currently reading the Odyssey for the first time and there are 2 interpretations it feels like you can make with Odysseus and his intereactions with characters like Calypso.

He's an unloyal twat who willingly sleeps with everyone woman he can (I feel like this seems to be the most popular female oriented take from what I know of a lot of modern retellings)

That actually, Odysseus has very little choice. The women he sleeps with are goddesses who entrap him in someway and the reality is that his one consistent goal is to get back to Penelope, the clever wife he loves. In effect Odysseus pretty much is being coerced and forced into these sexual relationships. Take Calypso for example, he can't kill her, can't leave, can't persuade her to let him go. He spends the years he's there crying, sobbing, desperate to leave but lays in her bed at night when she asks him to. This to me doesn't seem like a man who wants to be doing that, wants to be betraying his wife, but instead a man who has little choice. Admittedly as well, it's made clear that the goddesses (Calypso and Circe) have a sort of magic when it comes to coercing and getting people to do what they want and it's made clear that Calypso's goal is to have Odysseus stay as her husband forever. The moment he has a chance to leave, after Hermes forces Calypso's hand, he does so, refusing to stay and turning down immortality and by all accounts one of the most beautiful creatures on the planet. There are multiple women, mortal and immortal, in the books who are described as desiring Odysseus and as extremely beautiful. The immortal he sleeps with, but the mortal he does not despite the opportunities afforded him. This to me suggests he only sleeps with the immortal ones because he has very little real choice, who is he to go against a goddess? I personally believe that if he had a real choice, he would have been celibate for those 20 years until he returned home.

I think it's really easy to judge Odysseus at face value, that he's a cheat and liar and that he didn't have to do these things. But to me, my personal interpretation (which is what it is, you can have a different one and that's fine!) is that this man, this highly intelligent man, adores his wife, wants to be back home, but has very little choice. That at best he sleeps with these goddesses knowing that it will enable his survival and at worst he's literally forced through the coercive nature that is a goddess and her powers. It doesn't seem to me, especially with Calypso, that he wants to be there, that he really wants her or cares for her or desires her, it seems like a motion, something he has to do because he's forced to. This man spends his entire time crying and I suspect if he could have he would have killed her, but who can kill a goddess? A daughter of Atlas? Certainly not him.

It strikes me as well, that if he really were that much of a rake, then the mortal women he comes across who are described as beautiful and desiring him, he would also sleep with or even marry and stay with. But he doesn't.

It may be an unpopular interpretation, but I actually really like Odysseus and I personally believe he has little choice in these flawed actions and that in reality he's a victim, I don't believe Homer puts it forth as some sort of romantic ideal or the hero being rewarded.

Obviously, you don't have to agree. You can have your own opinion and that's fine.

#That being said I've only just got past Circe so maybe there's other parts of the story I haven't gotten to yet#but I'm a penelope/odysseus stan and I 'm tempted to rewrite the odyssey with odysseus very clearly a victim#it doesn't feel like he's this rake that people put him as in my opinion#the odyssey#odysseus#odysseus/penelope

133 notes

·

View notes

Text

I already made a post about it before, but since a lot of people are coming around for more Greek mythology content, I thought "Why not take off the dust from old talks?", and thus here is my redo-post about the Homeric vs Hesiodic tradition.

I am summarizing here greatly but... We all know that Homer's epics (The Odyssey and the Iliad), and Hesiod's works (The Theogony, Of Works and Days) form the "basis" of Greek mythology as we know it today, as they are the oldest literary records of Greek mythology we have, and the Ancient Greeks themselves shared the same opinion, even going as far as using them and analyzing them to understand their own religion.

And yet, despite this set of works being considered together as a "whole", Hesiod and Homer actually presented two different visions of the Greek mythology and the Greek pantheon, often contradicting - and many of the "There's thousands versions of a same myth" trend about Greek mythology comes from the fact that these two fundamental set of works were already in conflict.

Why? Long story short it is agreed that Homer was the oldest of the two, and that in his works he reflected an older, more primitive state of the Greek religion and Greek gods. Meanwhile Hesiod, the "youngest", collected a more modern and recent set of beliefs that would become the dominant Greek theology of Ancient Greece. There's a lot of interesting debate and scholarly study about this, but in this post I just want to collect and highlight a few key differences between the "Homeric" and "Hesiodic" traditions, to again remind people that you are not always forced to stick to one version, since already at the beginning of all there were TWO recorded versions, from which many many more different spawned afterward...

KEY DIFFERENCE 1: Everybody knows Hesiod's Theogony, and how from Chaos came Gaia and Ouranos, and from them came the Titans, and then the Olympians. One long genealogy dating back from the Earth and the Sky out of the primordial void... And yet Homer hints heavily at another cosmogony, where Oceanus/Okeanos and Tethys are not actually part of the Titan siblings (as Hesiod claims)... But the origin of all things. The parents of all the gods, and the source of all life, as many divine beings (from Hera to Hypnos) explain repeatedly. The clues scattered throughout the Iliad and the Odyssey point out to the fact the "cosmic couple" might have been originally the water deities of the sea and ocean, before being replaced by the sky-and-earth one ; and this puts under a very different light why the two stayed "neutral" during the conflict, and why Oceanos and Tethys would end up sheltering Hera during Zeus' attack against Kronos...

Key difference 2: Everybody knows the story of Aphrodite being born from Ouranos' sexual organs being cut off by Kronos and thrown into the sea... And yet Homer tells a very different story about Aphrodite being actually a daughter of Zeus. Her mother is a mysterious goddess named Dione - I say mysterious because outside of Homer, and a handful of other things, we know barely anything about her. Most of what we know is that she had an actual worship in the old Greek religion (the grove of Dodona was dedicated to her), and that all analysis and studies point out to her being a female version/counterpart of Zeus. If I recall well, from Homer making her a secondary character in his epics (with a famous scene of her comforting her wounded daughter), Hesiod made her a mere name dropped among the Oceanids.

Key difference 3: In a continuation of the previous difference, Eris, the goddess of discord, also has different parentages in both tradition. According to Homer, Eris was Ares' sister (and thus the daughter of Zeus and Hera) ; Hesiod rather described her as one of the many children of Nyx, the primordial goddess of the night. (In fact, in the Hesiodic tradition Eris took example on her mother and gave birth in turn to many malevolent and destruction personifications ; this was not the case in the Homeric works).

Key difference 4: The story of Hephaestus/Hephaistos being born of Zeus and Hera the... let's say "regular" way comes from the Homeric tradition. Hesiod actually depicts a very different birth-story ; and in quite a twist, most people today remember Homer's genealogy than Hesiod's one. For you see, in Hesiod, Hephaistos was actually conceived by Hera alone, without any male intervention. She had grown jealous of Zeus having a daughter of his own (with Athena coming out of his head). She basically interpreted this as her husband "showing off" and somehow trying to prove he did not need women to have children (I am extrapolating here but that's the core idea) ; so in return Hera decided to have a child all on her own too, and she managed to fall pregnant and have a son with her own power, no Zeus or other god involved... But the result was Hephaistos, ugly and lame.

Key difference 5: Homer placed a lot more focus on Helios than Hesiod. In fact, Helios is so present and so involved in the Homeric epics that he is basically the unofficial "thirteenth Olympian". And, while in Hesiod's Theogony the name "Hyperion" designates one of the Titans born of Gaia and Ouranos, and the father of Helios, Selene and Eos ; in the Homeric epics, instead "Hyperion" is a qualificative/synonym/alternate name of Helios himself, and not at all a distinct entity.

Key difference 6: In Hesiod's cosmogony, the Moirai are a trinity of goddesses, each with their specific name and function - the goddesses we know today. Hesiod even gives two CONTRADICTING birth-stories to explain the origin of the Moirai (if having two conflicting "founding fathers" wasn't enough, we now have a guy who contradicts HIMSELF). Hesiod alternatively describes the Moirai as either daughters of Nyx (and so part of these primordial deities of darkness and doom born somewhere in the mysterious beginnings of time) ; either as daughters of Zeus and Themis (and in this version they explicitely received their powers over fate from Zeus himself).

In Homer, the Moirai are much less defined and personified - in fact, many times - almost all the time - he refers to Fate/Destiny as a singular entity. Not only is the fate goddess singular (except for some parts of his epics that evoke a group of "weavers"), but she is as I said not very personified, not given any attribute, genealogy or description, to the point that... it seems that she was just a poetic metaphor, a rhetorical allegory, a personification more than a goddess. Instead, in the Homeric world it is Zeus that fills the role of the god of fate and destiny - changing fates and weighing destinities on his own ; a far cry from the future image of a Zeus that must bow to the laws of fate.

There are many, many more differences to point out between Homer and Hesiod - but I think those selected fews are enough to show that, even in its "foundations", Greek mythology kept offering alternative and variations ; and that by putting the ancient works back in a correct chronology order, we get fascinating evolutions (Oceanos and Tethys replaced by Gaia and Ouranos ; Zeus losing the paternity of many important goddesses ; Zeus losing his place as a god of fate ; Helios losing importance as time went on, entire deities disappearing such as Dione...)

#greek mythology#homer#hesiod#homeric tradition#greek gods#hesiodic tradition#moirai#zeus#dione#titans#aphrodite#eris#helios#hyperion#hephaestus#hephaistos#hera

37 notes

·

View notes

Note

[Again its very sappy] Very good, very good, very good!

So, to keep everyone from getting cavities, let's move the stage:

A food court in a shopping mall - because I doubt those were a thing 500 years ago and Mac doesn't want to stay at home all day.

A place with actual food and plenty of people to, ahem, snack on - what more could this monkey want?

And with juicy new future food, well, it seems like a good day, especially this thing called a 'burger'-

"Ehem!"

The glamoured six ears twitch at that, and his head swivels to the source of the sound to see...some human woman? He's not too versed on modern days fashion, but the clothing does look nice, Mac supposes.

The women gave them a look of disgust and pointedly asked at the darker monkey, "Should you be eating that with your weight?"

SWK is ready to go on the defensive (relationship in shambles or not, no bitch will be allowed to run her mouth like that at his Moon! Especially when he's pregnant!), but Mac calmly stands up, keeping eye contact with the woman. Then he grabs the big juicy burger and starts eating it in big bites, ripping with his sharp teeth, while still keeping eye contact. Unflinching and steady.

Whatever bravado the woman had was diminishing faster than a whole orchard of heavenly peaches with SWK in the area.

With the final bite down, Macaque then very widely and very toothily smiled.

Ever seen a rhesus macaque's (the species SWK and Mac are based on) chompers?

Mac used Intimidate! Wild Karen fled for the hills.

SWK meanwhile is 1/3 impressed at Mac's self-control, 1/3 amused at the spectacle, and 1/3 In Full Simp Mode.

Oh my, even separated from the au; Macaque really would be taken aback by how much food is available in the modern world. Like??? China has an infamous history of famine, and I could see Macaque not having a fun time roughing it when FF Mountain was burned. But now theres so much food that there's overabundance??

Wukong and Tang are def the ones that drag him to a food court/hawker centre to try out new dishes. Pigsy grumbled ofc cus; "I would've cooked you some if you asked."

Macaque: "But we have food at home???"

Wukong: "I mean yeah, noodles. But have you ever tried street food? Or cheese tea? Or- OH man! You don't even know that Peach chips exist!"

Macaque: "I once ate flatbread a man cooked using his own helmet. I stayed away from big cities when I could." :\

Tang, eyes already glazed with hunger: "Brace yourself then."

Cue Macaque having a brief sensory overload of smells (everything smells so good), sight (lots of things to look at), and Sound (so loud). Tang and Wukong are able to ground him enough so he doesn't leap away like a startled cat - noise canceling headphones quickly become Macaque's favorite modern tech. They find themselves a quiet corner of the food court to sample the wares of the modern world.

Macaque is cautious to try anything at first, but immediately gets enthralled by a regular ol' juicy cheeseburger grilling on a skillet - think of the burger thay made in The Menu. Meat, bread, and cheese? One sniff and he is off. It's like Homer taking the first bite of the Ribwich.

The other two are surprised how much he gets into it since he seemed to glance over the more traditional chinese street food places. Macaque is too busy having a religous experience with the first burger to realise that dips, sauces and other stuff can be put on them. They all end up campling outside the nearest McDonDons (anime joke) or local burger joint so Macaque can focus on one type of food for his first culinary expedition.

The a group of women sitting a table over make a catty comment about Macaque "not needing the extra weight" + "what is it with demons eating like that?". Tang is uncomfy cus he isn't sure how Macaque reacts to public rudeness, whilst Wukong is seconds away from going into defensive hero mode. Macaque just finishes his burger, teeth bared, without breaking eye contact with the women making the comments. Rude onlookers are terrifed, Tang is giggling to himself, and Wukong is in full "I love my terrifying mate" mode.

It becomes a ritual of sorts for them to take Macaque out for a new food each week as a bonding experience/enrichment. He ends up enjoying most things he can get his hands on, especially if said thing was originally on Wukong's plate >:) - Wukong complains but is secretly very much adores seeing his mate's more playful side. Macaque also develops a weird craving for cheese tea later in pregnancy for some reason.

Pigsy still proudly holds the title for the best noodles Macaque has ever eaten though.

#the monkey king and the infant#the monkey king and the infant au#lmk shadowpeach au#shadowpeach#pregnancy tw#food tw#lmk au#lmk tang#Sun Wukong and Macaque are MK's parents#lmk tmkati au story events

65 notes

·

View notes

Note

Can you make a post about the evolution of Greek art from the ancient times until now in modern age?

Because we often talk about the evolution of art but unfortunately we don't appreciate after ancient times the other art movements Greece went through the centuries.

That’s true! I am sorry for taking ages to answer this but I don't know how it could take me less anyway hahaha I made this post with summaries about all artistic eras in Greek history. I have most of it under a cut because with the addition of pictures it got super long, but if you are interested in the history of art I recommend giving it a try! I took advantage of all 30 pictures that can be possibly attached in a tumblr post and I tried to cover as many eras and art styles as possible, nearly dying in the process ngl XD I dedicated a few more pictures in modern art, a) because that was the ask and b) because there is more diversity in the styles that are used and the works that are available to us in great condition in modern times.

History of Greek Art

Greek Neolithic Art (c. 7000 - 3200 BC)

Obviously, with this term we don’t mean there were people identifying as Greeks in Neolithic times, but it defines the Neolithic art corresponding to the Greek territory. Art in this era is mostly functional, there are progressively more and more defined designs on clay pots, tools and other utility items. Clay and obsidian are the most used materials.

Clay vase with polychrome decoration, Dimini, Magnesia, Late or Final Neolithic (5300-3300 BC).

Cycladic Art (3300 - 1100 BC)

The art of the Cycladic civilisation of the Aegean Islands is characterized by the use of local marble for the creation of sculptures, idols and figurines which were often associated to womanhood and female deities. Cycladic art has a unique way of incidentally feeling very relevant, as it resembles modern minimalism.

Early Cycladic II (Keros-Syros culture, 2800–2300 BC)

Minoan Art (3000-1100 BC)

The advanced Minoan civilisation of Crete island was projecting its confidence and its vibrancy through its various arts. Minoan art was influenced by the earlier Egyptian and Near East cultures nearby and at its peak it overshadowed the rest of the contemporary cultures and their artistic movements in Greece. Colourful, with numerous scenes of everyday life and island life next to the sea, it was telling of the society’s prosperity.

The Bull-leaping fresco from Knossos, 1450 BC.

Mycenaean Art (c. 1750 - 1050 BC)

Mycenaean Art was very influenced by Minoan Art. Mycenaean art diverged and distinguished itself more in warcraft, metalwork, pottery and the use of gold. Even when similar, you can tell them apart from their themes, as Mycenaean art was significantly more war-centric.

The Mask of Agamemnon in the National Archaeological Museum of Athens. The mask likely was crafted around 1550 BC so it predates the time Agamemnon perhaps lived.

Geometric Art (1100 - 700 BC)

Corresponding to a period we have comparatively too little data about, the Geometric Period or the Homeric Age or the Greek Dark Ages, geometric art was characterized by the extensive use of geometric motifs in ceramics and vessels. During the late period, the art becomes narrative and starts featuring humans, animals and scenes meant to be interpreted by the viewer.

Detail from Geometric Krater from Dipylon Cemetery, Athens c. 750 BC Height 4 feet (Metropolitan Museum, New York)

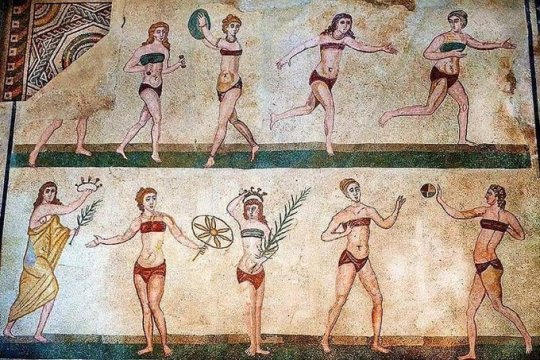

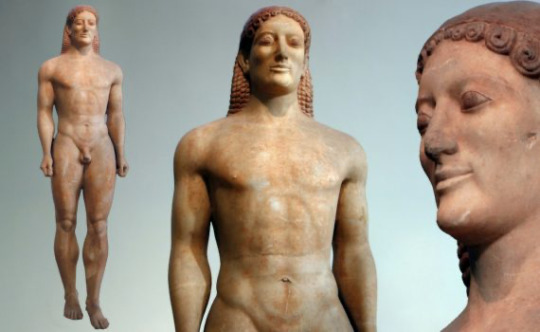

Archaic Art (c. 800 - 480 BC)

The art of the archaic period became more naturalistic and representational. With eastern influences, it diverged from the geometric patterns and started developing more the black-figure technique and later the red-figure technique. This is also the earliest era of monumental sculpture.

Achilles and Ajax Playing a Board Game by Exekias, black-figure, ca. 540 B.C.

Kroisos Kouros, c. 530 B.C.

Classical Art (c. 480 - 323 BC)

Art in this era obtained a vitality and a sense of harmony. There is tremendous progress in portraying the human body. Red-figure technique definitively overshadows the use of the black-figure technique. Sculptures are notable for their naturalistic design and their grandeur.

The Diskobolos or Discus Thrower, Roman copy of a 450-440 BCE Greek bronze by Myron recovered from Emperor Hadrian’s Villa in Tivoli, Italy. (British Museum, London). Photo by Mary Harrsch.

Terracotta bell-krater, Orpheus among the Thracians, ca. 440 BCE, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Hellenistic Art (323 - 30 BCE)

Hellenistic art perfects classical art and adds more diversity and nuance to it, something that can be explained by the rapid geographical expansion of Greek influence through Alexander’s conquests. Sculpture, painting and architecture thrived whereas there is a decrease in vase painting. The Corinthian style starts getting popular. Sculpture becomes even more naturalistic and expresses emotion, suffering, old age and various other states of the human condition. Statues become more complex and extravagant. Everyday people start getting portrayed in art and sculpture without extreme beauty standards imposed. We know there was a huge rise in wall painting, landscape art, panel painting and mosaics.

Mosaic from Thmuis, Egypt, created by the Ancient Greek artist Sophilos (signature) in about 200 BC, now in the Greco-Roman Museum in Alexandria, Egypt. The woman depicted in the mosaic is the Ptolemaic Queen Berenike II (who ruled jointly with her husband Ptolemy III) as the personification of Alexandria.

Agesander, Athenodore and Polydore: Laocoön and His Sons, 1st century BC

Greco-Roman Art (30 BC - 330 AD)

This period is characterized by the almost entire and mutually influential merging of Greek and Roman artistic expression, in light of the Roman conquest of the Hellenistic world. For this era, it is hard to find sources exclusively for Greek art, as often even art crafted by Greeks of the Roman Empire is described as Roman. In general, Greco-Roman art reinforces the new elements of Hellenistic art, however towards the end of the era, with the rise of early Christianity in the Eastern aka the Greek-influenced part of the empire, there are some gradual shifts in the art style towards modesty and spirituality that will in time lead to the Byzantine art. During this era mosaics become more loved than ever.

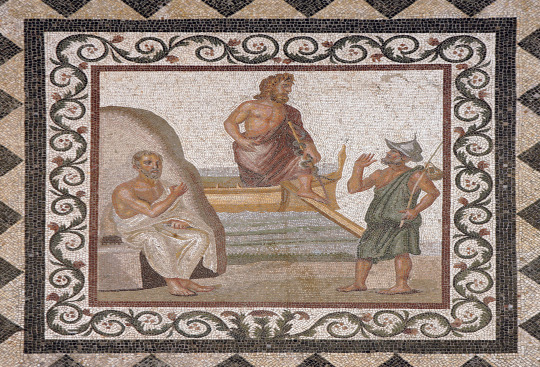

A mosaic from the island of Kos (the birthplace of Hippocrates) depicting Hippocrates (seated) and a fisherman greeting the god Asklepios (center) as he either arrives or disembarks from the island. Second or third century CE.

Introduction to Byzantine Art

Byzantine art originated and evolved from the now Christian Greek culture of the Eastern Roman Empire. Although the art produced in the Byzantine Empire was marked by periodic revivals of a classical aesthetic, it was above all marked by the development of a new aesthetic defined by its salient "abstract", or anti-naturalistic character. If classical art was marked by the attempt to create representations that mimicked reality as closely as possible, Byzantine art seems to have abandoned this attempt in favor of a more symbolic approach. The subject matter of monumental Byzantine art was primarily religious and imperial: the two themes are often combined.

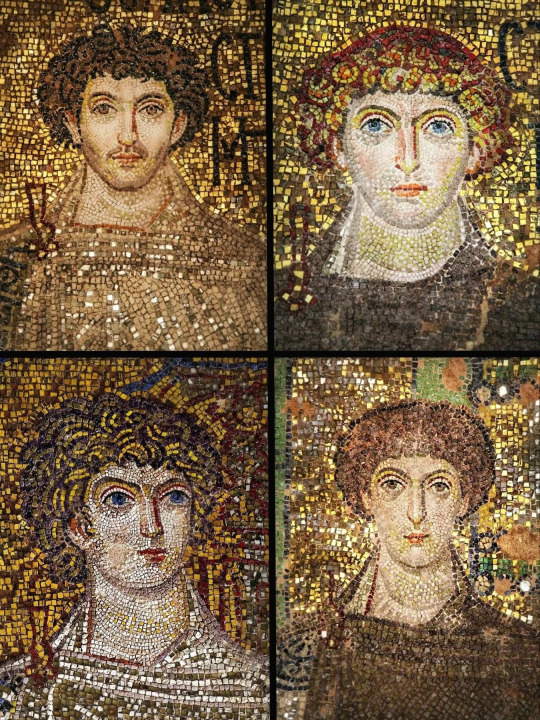

Early Byzantine Art (330 - 842 AD)

The establishment of the Christian religion results in a new artistic movement, centered around the faith. However, ancient statuary remains appreciated. Most fundamental changes happen in monumental architecture, the illustration of manuscripts, ivory carving and silverwork. Exceptional mosaics become integral in artistic expression. The last 100 years of this period are defined by the Iconoclasm, which temporarily restricts entirely the previously thriving figural religious art.

Mosaics in the Rotunda of Thessaloniki, 4th - 6th century AD.

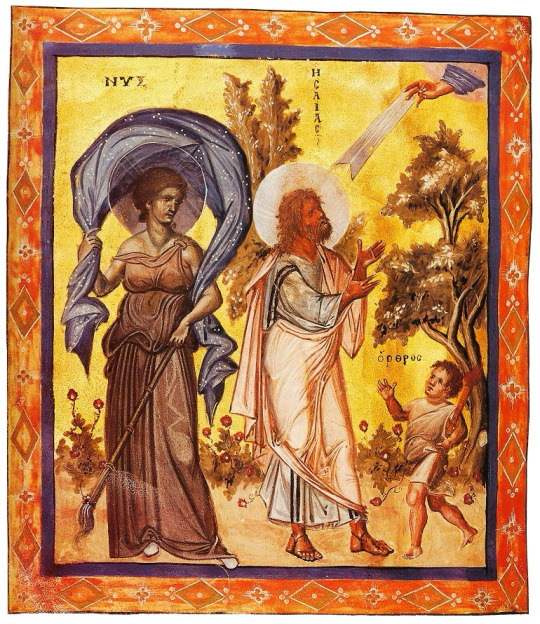

Macedonian Art & Komnenian Age (843 - 1204 AD)

These artistic periods correspond to the middle Byzantine period. After the end of the Iconoclasm, there is a revival in the arts. The art of this period is frequently called Macedonian art, because it occurred during the Macedonian imperial dynasty which generally brought a lot of prosperity in the empire. There was a revival of interest in the depiction of subjects from classical Greek mythology and in the use of Hellenistic styles to depict religious subjects. The Macedonian period also saw a revival of the late antique technique of ivory carving. The following Komnenian dynasty were great patrons of the arts, and with their support Byzantine artists continued to move in the direction of greater humanism and emotion. Ivory sculpture and other expensive mediums of art gradually gave way to frescoes and icons, which for the first time gained widespread popularity across the Empire. Apart from painted icons, there were other varieties - notably the mosaic and ceramic ones.

Paris Psalter, 10th century AD. Prophet Isaiah from the Old Testament in the company of the symbolisms for night (clear inspiration drawn from the ancient deity Nyx) and morning (Orthros, not to be confused with the mythological creature).

Palaeologan Renaissance (1261 - 1453)

The Palaeologan Renaissance is the final period in the development of Byzantine art. Coinciding with the reign of the Palaeologi, the last dynasty to rule the Byzantine Empire (1261–1453), it was an attempt to restore Byzantine self-confidence and cultural prestige after the empire had endured a long period of foreign occupation. The legacy of this era is observable both in Greek culture after the empire's fall and in the Italian Renaissance. Contemporary trends in church painting favored intricate narrative cycles, both in fresco and in sequences of icons. The word "icon" became increasingly associated with wooden panel painting, which became more frequent and diverse than fresco and mosaics. Small icons were also made in quantity, most often as private devotional objects.

Detail of Anástasis (Resurrection) fresco, c. 1316–1321, Chora church, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: byzantologist).

Cretan School (15th - 17th century)

Cretan School describes an important school of icon painting, under the umbrella of post-Byzantine art, which flourished while Crete was under Venetian rule during the Late Middle Ages, reaching its climax after the Fall of Constantinople, becoming the central force in Greek painting during the 15th, 16th and 17th centuries. By the late 15th century, Cretan artists had established a distinct icon-painting style, distinguished by "the precise outlines, the modelling of the flesh with dark brown underpaint, the bright colours in the garments, the geometrical treatment of the drapery and, finally, the balanced articulation of the composition". Contemporary documents refer to two styles in painting: the maniera greca (in line with the Byzantine idiom) and the maniera latina (in accordance with Western techniques), which artists knew and utilized according to the circumstances. Sometimes both styles could be found in the same icon. The most famous product of the school was the painter Domenikos Theotokopoulos, internationally known as El Greco, whose art evolved and diverged significantly in his later years when he moved in Spain and was involved in the Spanish Renaissance, and though it often alienated his western contemporary artists, nowadays it is viewed as an incidental early birth of Impressionism in the mid of the Renaissance’s peak.

Icon by Andreas Pavias (1440-1510), Cretan School, from Candia (Venetian Kingdom of Crete). The Latin inscription suggests the icon was meant for commercial purposes in Western Europe. National Museum, Athens. (Source: https://russianicons.wordpress.com/tag/cretan-school/)

Crucifixion (detail), El Greco (Doménikos Theotokópoulos), ca. 1604 - 1614.

Heptanesian School (17th - 19th century)

The Heptanesian school succeeded the Cretan School as the leading school of Greek post-Byzantine painting after Crete fell to the Ottomans in 1669. Like the Cretan school, it combined Byzantine traditions with an increasing Western European artistic influence and also saw the first significant depiction of secular subjects. The center of Greek art migrated urgently to the Heptanese (Ionian) islands but countless Greek artists were influenced by the school including the ones living throughout the Greek communities in the Ottoman Empire and elsewhere in the world. Greek art was no longer limited to the traditional maniera greca dominant in the Cretan School. Furthermore, the Heptanesian school was the basis for the emergence of new artistic movements such as the Greek Rocco and Greek Neoclassicism. The movement featured a mixture of brilliant artists.

Archangel Michael, Panagiotis Doxaras, 18th century.

Greek Romanticism (19th century)

Modern Greek art, after the establishment of the Greek Kingdom, began to be developed around the time of Romanticism. Greek artists absorbed many elements from their European colleagues, resulting in the culmination of the distinctive style of Greek Romantic art, inspired by revolutionary ideals as well as the country's geography and history.

Vryzakis Theodoros, The Exodus from Missolonghi, 1853. National Gallery, Athens.

The Munich School (19th century Academic Realism)

After centuries of Ottoman rule, few opportunities for an education in the arts existed in the newly independent Greece, so studying abroad was imperative for artists. The most important artistic movement of Greek art in the 19th century was academic realism, often called in Greece "the Munich School" because of the strong influence from the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of Munich where many Greek artists trained. In academic realism the imperative is the ethography, the representation of urban and/or rural life with a special attention in the depiction of architectural elements, the traditional cloth and the various objects. Munich School painters were specialized on portraiture, landscape painting and still life. The Munich school is characterized by a naturalistic style and dark chiaroscuro. Meanwhile, at the time we observe the emergence of Greek neoclassicism and naturalism in sculpture.

Nikolaos Gyzis, Learning by heart, 1883.

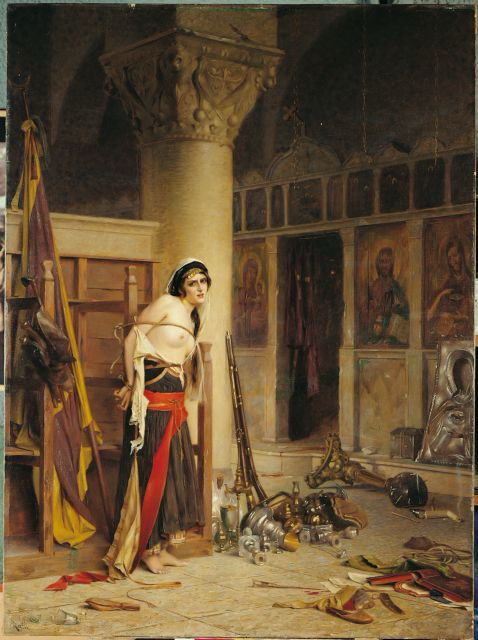

Rallis Theodoros, The Booty, before 1906.

20th Century Modern & Contemporary Greek Art

At the beginning of the 20th century the interest of painters turned toward the study of light and color. Gradually the impressionists and other modern schools increased their influence. The interest of Greek painters, artists changes from historical representations to Greek landscapes with an emphasis on light and colours so abundant in Greece. Representatives of this artistic change introduce historical, religious and mythological elements that allow the classification of Greek painting into modern art. The era of the 1930s was a landmark for the Greek painters. The second half of the 20th century has seen a range of acclaimed Greek artists too serving the movements of surrealism, metaphysical art, kinetic art, Arte Povera, abstract excessionism and kinetic sculpture.

Yiannis Moralis, Two friends, 1946.

Art by Giannis Gaitis (1923-1984), famous for his uniformed little men.

By Yorghos Stathopoulos (1944 - )

Art (detail) by Nikos Engonopoulos (1907 - 1985)

Folk, Modern Ecclesiastical and Secular Post-Byzantine Art

Ecclesiastical art, church architecture, holy painting and hymnology follow the order of Greek Byzantine tradition intact. Byzantine influence also remained pivotal in folk and secular art and it currently seems to enjoy a rise in national and international interest about it.

A modern depiction of the legendary hero Digenes Akritas depicted in the style of a Byzantine icon by Greek artist Dimitrios Skourtelis. Credit: Dimitrios Skourtelis / Reddit

Erotokritos and Aretousa by folk artist Theophilos (1870-1934)

Example of Modern Greek Orthodox murals, Church of St. Nicholas.

Ancient Greek philosophers depicted in iconographic fashion in one of Meteora’s monasteries. Each is holding a quote from his work that seems to foreshadow Christ. Shown from left to right are: Homer, Thucydides, Aristotle, Plato and Plutarch. This is not as weird as it may initially seem: it was a recurrent belief throughout the history of Christian Greek Orthodoxy that the great philosophers of the world heralded Jesus' birth in their writings - it was part of the eras of biggest reconciliation between Greek Byzantinism and Classicism.

Prophet Elijah icon with Chariot of Fire, Handmade Greek Orthodox icon, unknown iconographer. Source

If you see this, thanks very much for reading this post. Hope you enjoyed!

#greece#art#europe#history#culture#greek art#artists#greek culture#history of art#classical art#ancient greek art#byzantine greek art#christian art#orthodox art#modern art#modern greek art#anon#ask

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE ILIAD: FOR DUMMIES ☀️ MASTERPOST

just kidding you're not a dummy, you're some hot stuff right there!

i will be going through the entire iliad and giving you a general overview, some interesting plot points, additional context, and some other analysis tools to better help you understand the epic!

This post will serve as a table of contents (at the end) to my Iliad posts and a general overview that I will be constantly updating! I am using the Richmond Lattimore translation of the Iliad, alongside my companion book by Malcom M. Wilcock

Before we get into analyzing the actual Iliad, we need to get into some essential questions and context about the book

WHAT IS THE ILIAD:

The Iliad was written by Homer (this is actually debated but we can get into that later) around 750 and 550 B.C.E.

At its core, the story is about heros and humans. It's an Iron Age poem about an event, the Trojan War, that was supposed to have taken place in the Bronze age. The Iliad is considered to be a poem comprised of multiple books, 24 to be exact

This story is only a few days of the tenth and final year of the Greek siege against the city of Troy- this means it relies on the audience already knowing most of the basic details about the Trojan war and the gods themselves (don't sorry, I will provide this for you as we go along)

WHO IS HOMER:

The age old question: who the fuck is Homer?

Literally nothing is known about this dude except that he wrote (or was credited with writing) the Odyssey and the Iliad

People have referenced his writings for EONS. Archilochus, Alcman, Tyrtaeus, Callinus, and even Sappho have referenced the poems of Homer in their own works. These also were popular in fine art in the late 7th century B.C.E.

There is a general consensus that Homer was from Ionia- a territory in western Anatolia or modern day Turkey that was populated by Greeks who spoke the Ionian dialect, aka the birthplace of Greek philosophy. Want more info on Ionia? Click Here!

His descendants were called the Homerids/Homeridae

There is scholarly debate on if he even wrote both the Iliad and the Odyssey, or if he only wrote one, etc etc etc. This is due to some very specific differences in the structure of the words used (like the use of short vowels, and the seemingly unimportant semivowel of the digamma being missing from the epics...yeah it's a lot)

The poems were reproduced ORALLY. This means that the poems were passed down by word of mouth, which if I were to sit and listen to this entire book via a guy singing at me...idk man I think I would leave

All of this to say, we really don't know who Homer is. There's a lot more information about what he could have looked like, if he really did write the Iliad, and a million other things, but I've already talked your ear off and we haven't even gotten into the book yet. If you want more information about Homer, check out my sources at the end of the post!

WAS THE CITY OF TROY REAL:

Yeah. There were nine layers exposed at the site of where Troy was expected to be, and nearly fifty sublayers at the mound of Hisarlik

Troy was a vassal state: meaning it had an obligation to a superior state, which happened to be the Hittite Empire

Troy had a lot more allies than original fighters in the city, meaning they had many language barriers- making the army harder to control than the unified Greek enemy.

THE STYLE OF THE ILIAD:

Cause - Effect - Solution

The poem is concluded with a mirror image of its beginning: an old man ventures to the camp of his enemy in order to ransom his child

The poem foreshadows the death of Achilles in MULTIPLE passages! He knows he is destined to die young if he fights at Troy, and the demise of his lover (don't fight me on this) Patroclus gives us an even more extended foreshadowing of the grief that is to come

When Achilles dies, Thetis (his mom) takes his body from the pyre and takes him to a place called the White Island. It's not clear whether he is immortalized BUT the reference to Achilles funeral in the Odyssey states that Achilles is cremated and his bones are placed in a golden urn along those of Patroclus, and the urn is entombed under a prominent mound (tsoa fans...you're welcome)