#....perhaps i should read temeraire

Text

landfall: chapter 2

On a bright fateful morn, Jack Sparrow brings rumors of the Black Pearl and her crew of the damned to Port Royal. In theory, the ship should be no match for the dragon Tempest and his Captain Norrington — but the Pearl harbors dangerous shadows of her own.

or: potc, but temeraire, multi-chapter wip. sequel to windfall

A flash in the water catches her eye. The spine of a large fish breaks the surface. She peers closer and — no, it is not a fish, but Barbossa’s dark dragon, miraculously keeping pace with the Pearl. Lookout swims just below the surface of the water. His colors — black-blue scales with stark white dappling — make him nearly invisible to the untrained eye. Elizabeth watches him swim, entranced, her stubbed toe forgotten.

At midday Lookout finally bursts from the water. He circles the Pearl once, his wingbeat not unlike the snapping of sailcloth, then lands on the deck directly in front of the captain’s quarters. There is just enough space for him to curl around the capstan — his tail drapes over the side of the ship into the water, yes, but it must be comfortable enough, for he closes his eyes against the sun and relaxes to nap. The crew steps over his thick tail like he is a minor obstacle, clearly used to such behavior.

Elizabeth holds her breath. Perhaps the crew placed Lookout here to deter her from escaping (as though she has anywhere to go). They could not know that Elizabeth has spent most every day of the last three years in the immediate presence of a much larger dragon. With a rational amount of fear and not a mote more, Elizabeth crouches before the doors to the cabin and pushes one open, just slightly.

“Lookout? Can you understand me?” Elizabeth whispers.

Lookout’s ears flick irritably. “Yes,” he says. He opens his mouth only enough to growl the word.

“Then help me,” Elizabeth pleads. She inches forward. “I can offer you treasure beyond your imagination, amounts beyond what fits in a ship’s hoard.”

“Leave me be. Every human lies to get what they want. You are no different.”

(read here on ao3!)

#pirates of the caribbean#james norrington#elizabeth swann#*fic#james and the giant lizard#or: the one where i have to rewrite some of the most iconic scenes in modern cinema :—)

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

More Dragon Marshalate AU Stuff

Post 1

Post 2

Soult's ADCs snippet

napoleonic marshalate dragons au chronological tag

Answering questions because I love the sound of my own typing and then some nattering about psychic dragons which get funky because you should never trust me with worldbuilding

i'll write dragon snippets for the other dragon marshals i just am easily baited into writing stuff based on what people say to me

@impetuous-impulse

If Desirée is a dragon, then her sister Julie and her niece, Honorine Anthoine de Saint-Joseph, would also be dragons. This would mean that Joseph Bonaparte and Marshal Suchet both married dragons.

Checks out! I think if we do turn a bunch of people into dragons but leave a bunch of people as human, and we don't want to break history too unbelievably in this era, we are probably going to have to treat dragon-marriage as equivalent to human marriage. But then some of the humans can also be simultaneously dragon married and human married probably.

Also, thinking of the Clary clan as some kind of urban dragon family is kind of funny.

i also love the idea of urban dragons, they'd have to be fairly small but yes

but also im going to babble a bit about psychic powers and how urban dragons miiiight work maybe

Other question: are the dragons ladies subject to similar constraints as human ladies in this era?

I want to say nope! Which probably raises more questions about the ladies that we've turned into dragons, but as I've written, dragons have no physical sex, any two dragons can make eggs, both dragons get sleepy and broody after having eggs.

---

@josefavomjaaga

Also, now I wonder if maybe, this whole "shapeshifting into a human" thing is something that all/most dragons might be able to learn. […] Unless of course they want to be closer to their favourite humans… Okay, so admittedly I just want to see Soult getting desperate over trying to learn shapeshifting so he can be with Louise 😋.

The younger and smaller dragons can learn enough dexterity with their claws to flip the pages of a book, to manipulate a quill, to peruse their own correspondence privately. The larger ones boast more strength and fire, flying higher but not further, but their claws that can take down horses and monsters with a single slash lose the precision for such delicate affairs.

Perhaps that is why the dragon Soult, once called "Jean-de-Dieu" by his family, admires the paintings he is so well known for collecting. No dragon as he can craft such deft and delicate brush strokes.

It is in the presence of these paintings that he asks his ADCs to place the letters before him, so he may read with eyes as sharp as an eagle's sight. But he must ask them to turn the pages, and he must ask them to draft his replies, and ever since the dragon grew beyond the size of a horse he has been so very frustrated with this lack of privacy.

But he must do with what he can.

Today it is Saint-Chamans at his side, and Saint-Chamans can hardly hide his confusion as he reads the letter. "Your excellency, this is a children's tale- why are you asking after such things?"

The great maroon dragon lets out a huff of hot air. He is not interested either in fairy stories and children's games, but… There is a line of inquiry I am pursuing personally.

He does have his valet perform this job for him, often. He does not strictly need the ADCs to do this.

But the valet is friendly with Louise, and he cannot have her worry.

And if there is a chance that one day he may come up to her and embrace her as an equal, then he must pursue it.

----

Thought process here:

Dragons in Pern are telepathic as in they communicate by speaking in your head -> to really differentiate this AU from Temeraire, we can focus more on Weird Magic but not to the extent that it's Extremely High Fantasy -> telepathy can be extrapolated to other things -> how do we get large dragons participating in city life????

So

Dragons here can telepathically communicate with people that they can see and that are in a small radius around them, equivalent to shouting at them

Dragons with their favourite people can extend that reach further and can communicate with them even without seeing them in that extended reach

Berthier Dragon is a weirdo who has managed to have a very large range with people he isn't connected to and can also multitask a little bit so he's. like a phone operator. yes this does change a bunch of things to have that instant feedback but I think both he and Napoleon are aware of the dangers of relying on a single tiny dragon

(obviously berthier dragon is. in love with madam visconti. and has a shrine to her.)

But what if dragons with their favourite people can not just pass on their communications but other senses

It may depend on the dragon? Some can send impressions of the emotions they feel, some can send sensory information, but also it might be fun if the human can send stuff back

this is a little funky but I am imagining that some dragon-human pairs can have this weird kind of consensual possession thing going on where the dragon "rides" along with the human's senses

So human cities are not really built for really large dragons - the edges of the city do have dragon and human accommodations, but only dragons horse sized and smaller can really go into the middle of the city

The "riding along" or weird possession thing is basically, large dragons who are too big to go into cities and ballrooms can "ride along" with their favourite people and experience things like extremely expensive balls

To prevent this from being used for spycraft too much, maybe the possessed person's eyes turn the colour of the dragon's

this is kinda creepy and weird but i think it can be romantic, and of course the possessed person can stop the possession at any time, the dragon doesn't actually have control over the human's actions and can only just experience sensory input and telepathically speak to them, so the human has to convey what the dragon's saying

#cadmus rambles#cad rambles about dead frenchmen on main#marshalate dragons au#dragons as cavalry au#cadmus writes

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

This Dragon/Temeraire AU is driving me feral (half-intended).

Okay, so with Bea, are you thinking her parents are both Chinese, or just one of them?

Because I'm thinking maybe only her mom is from China, and yeah she's a diplomat, and her dad is British diplomat. And so that creates a tension of her mother thinking it's okay for Bea to be working with dragons, but her father will never like it.

But also, they could both be Chinese diplomats stationed long-term in the UK. If Bea had grown up in China, she would probs deserve one of the more important dragon breeds, but not an Imperial or Celestial.

So, in Britain, they kind of let Bea work with Temeraire because he's a Celestial. But maybe they also low-key hate it because why is Bea working with a crew. That's so... debasing.

Temeraire, on the other hand, loves Bea. I am thinking, this story would be set maybe a decade after Laurence has passed away (rip)? And Temeraire loves his crew now, but you know how the British Dragon Corps is, they're kinda rough and tumble. Then along comes Bea who's very proper and reads Chinese books with him (perhaps, Bea even respectfully gives him a present of a book when they first met) and she reminds him so much of Laurence sometimes, and he is all starry-eyed over her for it.

Then when Bea makes captain, her mother uses her influence so that Bea gets Temeraire's hatchling. But also! Temeraire helps her mom with it because he loves Bea and it's the only way he would let her go LMAO.

So yes, Bea comes into this Celestial thinking she doesn't deserve it. And maybe most of the other people in the British corps thinks the same thing too, but it's not like any of them could stop both Temeraire and an important diplomat.

Bea is a conundrum to them, and it's even a relief when she's sent away. The only one who has a hard time accepting that she has to go away is Temeraire.

oh same! the temeraire dragons are my favourite way of doing dragons in anything ever.

with bea yeah i am thinking that her mum is from China & her father is British. & they argue at length about the optics of sending their 7y/o to work with dragons, but since it’s tem & it isn’t far from their estate, he agrees, so long as she also recieves a classical education. which is how we end up with a beatrice who should, by all rights, be half-wild, but who is also taught manners and etiquette and fencing and, thanks to tem and his & laurence’s library, she also learns advanced mathematics and physics and aeronautics and philosophy and poetry and a kind of eclectic mixture of disciplines.

BUT she also works on tem’s crew and flies with him & listens to him for hours talking about his adventures. & she dreams of seeing the world on dragonback too. so she’s in this weird position of working a dragon crew, but tem clearly likes her more than a normal crew member, meanwhile she’s also educated and wealthy and not like the children she grows up with. so she ends up slightly isolated, quite lonely.

& tem, seeing this, decides that bea is going to have a celestial, & nobody can change his mind about it. he adores this deeply formal and stuiously proper girl who shows up the first day with a book which she reads to him standing at attention and then gradually falling asleep against his wing. & she’s very like laurnce because she’s a fish out of water & very stiff & mannered but also indescribably warm and genuine.

so yeah, even though, barring exceptional longwing circumstances, Nobody makes captain at eighteen, he just insists on it, and the corps want a celestial so they shrug. but then, ofc, Something Happens with bea and her parents do not want her in the corps so they strongarm the ocs into laying claim to her (bc yes they DO need celestials) and they assign lilith as her lieutenant while lil waits for Halo to secure the succession. (i love the idea of a tem & beamom tag team where no they don’t like each other but YES they will work together for nepotism purposes. neither of them give a damn about the fairness of it, & tem knows that beatrice deserves it anyway)

so now bea is in this strange organisation with a legendary dragon and a legacy hanging over her (& her secret, which in 19th century Britain could get her in serious trouble). it’s perfect i love her and meddlesome tem.

#going so feral fr about this#i have like the first part of it outlined in my head#(i see ur three other gorgeous amazing asks but i'm going hiking right this second so i will reply later)#this au!!!#wn temeraire au

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Goodreads is finally keeping me on the straight and narrow re: remembering books that I want to read and am in fact currently reading but it'll only list specific books so other things on the tbr list:

Finish the Temeraire series hopefully while being able to remember what happened in the first like two or three books

That Earthsea anthology that's been sitting on my shelf and also Ursula K. Le Guin in general

While I'm at it, watch the earthsea movie

I need to look into the Vorkosigan saga??

U know what I should try Abhorsen again too

I am CURRENTLY making headway here!! But in case i forget again the Witcher series

Finally finished feet of clay and I can start hunting for a copy of the next city watch book (thud?? Jingo?)

Also perhaps eventually the rest of the discworld books, there's a copy of monstrous regiment at the library

Vathara has me curious about the Valdemar series and the name Mercedes Lackey keeps scratching at my brain like did I see something that looked really good or are her books just everywhere or does her name just sound like a fantasy author

More c.s. lewis essays, of other worlds and an experiment in criticism have me hooked

More Tolkien essays too while I'm at it and le guin's essays are always on the list

Do I want to get into the rest of the enders game books? Unkown

Victoria Goddard, just in general, the hands of the emperor is on my top faves list

I wasn't hooked by The Thief but I have been informed that it's not the strongest book in the series so PERHAPS the other Meghan whaler thief books (queen's thief series??)

All those free books from the tor book club

Perhaps more asimov

OH YEAH William Gibson

On a general level I want to look for more sci-fi and fantasy written by women, I'm very curious to compare with "classic" spec fic written by white men bc I've noticed some common elements (kind of more "zoomed out" pov, generally srs face tone, lots of world building but perhaps in specific areas? It's not something I've quantified it's just ~vibes~) and inquiring minds want to know if that's influenced at all by the gender of the writer. You know, by that same thought, I should look into classic sci-fi/fantasy by poc and literally anyone not from Britain or America. Witcher is Polish. What else is going on with Slavic and East Asian and Middle Eastern and African literature. I got into xianxia recently and was hit over the head with the incredibly obvious fact that western spec-fic is, in fact, not the end-all be-all of people writing about magic and monsters and the future. I think I heard a lady in Japan wrote a very important piece of literature that qualifies as one of the earliest novels??? I need to do some research.

AH the master and commander series

#to read#single greatest challenge of my life is remembering what i want to do long enough to do it#noodle speaks#a microcosm of my thought process: i have an idea#start the idea cant remember parts of my idea get distracted in the middle and suddenly#remember what i was trying to think of earlier

1 note

·

View note

Text

Goodnight

Just a random thing I wrote, hope you enjoy!

Laurence was laying on Temeraire's forearm under a warm blanket. The breeze had become chilly in the evening, rushing through the trees. Temeraire had insisted on the warmest blanket they had in the pavilion despite the newly added screens to keep out the wind and the heated flooring. The were reading one of the newer books that Tharkay had purchased for them when he was on business in Edinbrugh.

Laurence only barely managed to stay awake through the latin calculations, Temeraire nudged at him when he paused too long for the second time on the same page.

"Laurence, perhaps you should retire." Temeraire said, he comfortingly rubbed his nose against his back, his tone apolegetic. "It is only that you seem rather tired and you keep nearly falling asleep."

"I do apologise, my dear." Laurence patted the dragon on the nose. "I suppose it has been a long day."

"It was a rather exciting day wasn't it." Temeraire said looking out over the house. The lights were twinkeling invitingly in the windows. "I never thought helping the tenants could be this rewarding. But Laurence you really should go sleep. Tomorrow we do have an early start."

"Very well" Laurence laughed, rising. He folds the blanket and puts it in the chest.

"Good night, my dear." Laurence said warmly he leaned against the dragon's warm nose for a moment, Temeraire rumbles affectionately and Laurence is gratefull that their days of fighting are over and that they could have these moments of leisure, without having to worry about what the next morning might bring.

As Laurence entered their room Tharkay is already in the bed, a candle burned on the nighttable and he had a book in his hands. The fire of the candle is reflected in Tharkay's much hated reading glasses. Laurence smiled at this image and Tharkay gives him a glance with one of his eyebrows raised. Laurence still thought the oval spectacles looked rather endearing on him, he chuckled, remembering the first time Tharkay had put them on, chagrined that he had needed them in the first place.

Another eyebrow was raised at the sound of his chuckle. Laurence simply smiled at him, he took some delight in the way Tharkay's eyes narrowed at him while he moved across the room to prepare for bed. Tharkay made an appreciative sound behind him when Laurence undressed, Laurence blushed, throwing an embarrased look over his shoulder. Tharkay had taken off his glasses, and put them aside with his book. He was smiling a bit too smugly.

Laurence pulled his nightshirt over his head, behind him Tharkay shifted onto his side and before Laurence could move into the bed Tharkay opened the blanket for him. Laurence slid gratefully under the covers, immediately he wrapped his arms around Tharkay. Together they settled, both of them comfortable next to eachother.

"Will, you have release me or I am afraid the candle will have to keep burning."

Laurence tightened his hold on Tharkay smiling into his neck.

"Let it burn." Laurence whispered into Tharkay's neck, he could feel the resulting shiver travel through Tharkay's body with how closely they were entwined.

He felt Tharkay's chuckle more than heard it.

"There is still two hours left on that candle."

"Hmmm, but you are so nice and warm."

"Oh you, I am not your personal bed warmer mr. Laurence." Tharkay said a laugh in his voice.

Laurence loved these moments, the moments where they laughed together about nothing at all, where just laying together was enough. No wars to worry about, no figthing to be had in the morning. Just the sun waking them up and steaming cups of tea beside their papres in the morning. Laurence buried his face in the curve between Tharkay's neck and his shoulder, smelling his skin. Tomorrow the three of them would fly to the village to speak with the farmers about the land, but before that they would break their fast in the pavilion with Temeraire. But at that moment they were content together in the light of the flickering candle, talking to eachother quietly until eventually the candle burned out and they both drifted off into sleep.

#Temeraire#wilzing#william laurence#tenzing tharkay#My fic#post canon#laurence/tharkay#fluff#wholesome

21 notes

·

View notes

Note

Ooohhh I have some smol prompts if you want them:

Laurence stupidly getting himself hurt and Tem is def not being a nursemaid.

Just Laurence being a dad

Temeraire and Granby learning of Barstowe (Laurence is already regretting ever mentioning him)

Temeraire has questions about love and if Laurence has ever been in love and with who.

For the Laurence gets wings au, maybe Tem teaching Laurence some tricks? Or Volly trying to teach Laurence some tricks?

Use these at your own leisure! Have fun writing whatever it will be.

For #1, i am very drunk so I apologize if it makes no sense:

“My dear, I have told you - “

“I am not fussing!” Temeraire insists, nudging Laurence. He winces but pretends this contact doesn't hurt. “It is only that you should take better care of yourself; you cannot complain if I point it out, when you seem to be so careless.”

“He has a point,” comes Tenzing's helpful response.

Laurence only frowns. It's just a broken arm, and gained through the most embarrassing circumstances imaginable; one of Tenzing's cooks slipped and dropped a pie, and in attempting to help her Laurence floundered himself. He'd slipped through the wet filling, crashing against a statuette and down the stairs in a ridiculously farcical fashion. He is heartily glad that no one else saw; but the injury is harder to ignore.

“Accidents do happen, Temeraire. Pray do not fret about it.”

“Oh, of course I will not; but perhaps you should hire an assistant,” the dragon suggests, nudging Laurence again. “Or a doctor. Or - “

“I think I shall manage,” says Laurence dryly.

Temeriare harrumphs, plainly unsatisfied, until Tharkay assures him that he will watch over Laurence “with all the diligence you might imagine.”

Which is purely fiction, Laurence hopes. He surely cannot warrant any real looking-after.

Except that the next day Tharkay brings his luncheon already cut, asking if he needs help with his shaving (a situation that Laurence has entirely ignored). When they retire outside to read to Temeraire, Tenzing asks whether he should turn the pages of the book, as though this is some laborious tasks.

When Laurence was a midshipmen on the USS Triumpant he broke his arm and was resoundly despised by his fellows for being such an inconvenience. He cannot help but blush when Tharkay insists on holding the book for him to read.

“I suppose it is alright you broke your arm,” Temeraire concedes at last, looping his tail around them both, “Since you are still whole, and able to speak; and of course we are here to listen and help you.”

And if Laurence finds it a bit hard to reply, through the weight in his throat, Tenzing doesn't say anything.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Temeraire’s Dragons

Perhaps it’s because winter puts me in a melancholic mood, but I have begun re-reading the Temeraire series. To my joy, the books remain every bit as good as I remember them: this is curious enough, for the basic premise of Temeraire is the Napoleonic Wars(with dragons!), and I don’t hold many “dragon-rider” novels in a very high esteem.

The concept itself is very interesting, but most of these novels tend to neglect the worldbuilding aspect: the logistics a dragon-riding force would need to be operative, the impact creatures such as dragons would have on a society and the world around them(specially if they are sapient), or the dragons themselves aren’t explored much.

And then there is how whole pages are dedicated to discourses about the intrincancies about their place in the world, the exceptional nature of the bonds that join rider and dragon(be they based on trust, camaraderie, magic... or a mix of the three), and the equally exceptional reasons for it, that’s just the issue; they tell, don’t show. The narrative always ends up turning around to the riders: the riders are who are properly fleshed-out, the ones who get to grow as characters, who develop new relationships, whose personalities are explored; the riders are who carry the plot.

Yes, the dragon is there, and they advise and protect their charges with all their wisdom and prowess, but if there aren’t any interactions beyond that, both the relationship and the character fall flat. They are nothing but a prop, a conduit through which the qualities of the riders can shine through all the brighter: indeed, there are some tales that seem to be less about the relationship between dragon and rider and more about showing how great the protagonist is, to have gained the loyalty of such a being.

The knot of the question is this: perhaps that’s the reason I enjoy the Temeraire books so much: not only there is a sound attempt to explore the logistics of dragon-handling, but the series makes a point of showing how the presence of dragons inluenced the different cultures around the world.

And finally there are the dragons themselves, who these works depict as individuals, who don’t do things just because “they are dragons, and that’s what dragons do”, as they have their own tastes, ideas and opinions. In the second book, Temeraire even wonders what would happen should he decide not to fight for England!

However, that’s not to say dragons think and act exactly the same way humans do: indeed, one of the highlights of Naomi Novik’s dragons is how their minds work. Their emotions are recognizable enough for the reader to easily empathize with them, but they have preferences, criteria and thought patterns that mark them as distinctly other.

Tl;dr: On the Temeraire series, it matters that dragons are dragons, while in other novels, there are times it seems like you could put talking horses in their places without any issue.

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Temeraire

I almost feel as though I should belch loudly, and possibly indecently. Perhaps exude a brief puff of flame as well, twould only be appropriate.

So, when I do read, it tends to be both voraciously and eclectically. While I tend to return to the three pillars of fantasy, science fiction, and horror, I do like a nice cozy mystery on occasion, or a nice naval piece set at the tail end of the 18th century. You can thank Richard Bolitho for that last one.

So it surprises no one that if you take Napoleon and Nelson, and liberally mix in a few dragons that I would not at least be tempted. It surprises people even less that having already expressed a fondness for the cadence and style of Naomi Novik’s writing that I devoured Her Majesty’s Dragon within the weekend.

It was delightful. Now I just need to distract myself until I can procure the next book in the series.

8 notes

·

View notes

Link

What separates these works from the Harry Potter fanfiction you find online may come down to snobbery. There is an undercurrent of misogyny in mainstream criticism of fanfiction, which is widely accepted to be dominated by women; one census of 10,500 AO3 users found that 80% of the users identified as female, with more users identified as genderqueer (6%) than male (4%). Novik has spent a good deal of time fighting against fanfiction’s stigma because she feels it is “an attack on women’s writing, specifically an attack on young women’s writing and the kind of stories that young women like to tell”. Which is not to say that young women only want to write about romance: “I think,” Novik says, “that [the popularity of fanfiction amongst women is] not unconnected to the lack of young women protagonists who are not romantic interests.” Devotees of fanfiction will sometimes tell you that it’s one of the oldest writing forms in the world. Seen with this generous eye, the art of writing stories using other people’s creations hails from long before our awareness of Twilight-fanfic-turned-BDSM romance Fifty Shades of Grey: perhaps Virgil, when he picked up where Homer left off with the story of Aeneas, or Shakespeare’s retelling of Arthur Brookes’s 1562 The Tragical History of Romeus and Juliet. What most of us would recognise as fanfiction began in the 1960s, when Star Trek fans started creating zines about Spock and Captain Kirk’s adventures. Thirty years later, the internet arrived, which made sharing stories set in other people’s worlds – be they Harry Potter, Spider-Man, or anything and everything in between – easier. Fanfiction has always been out there, if you knew where to look. Now, it’s almost impossible to miss.

In the last few years, fanfiction has enjoyed something of a rebrand. Big-name authors such as EL James, author of the Fifty Shades books, and Cassandra Clare, who has always been open about writing Harry Potter fanfiction before her bestselling Mortal Instruments series, have helped bring it into the mainstream. These days, it’s fairly common knowledge that some people just really like writing about Captain America and Bucky Barnes falling in love, or Doctor Who fighting demons with Buffy. The general image of fanfiction has brightened somewhat: less creepy, more sweetly nerdy.

But the divide between fanfiction and original writing holds strong. It’s assumed that if people write fanfiction, it’s because they can’t produce their own. At best, it functions as training wheels, preparing a writer to commit to a real book. When they don’t – as in the famous case of Fifty Shades, which one plagiarism checker found had an 89% similarity rate with James’s original Twilight fanfiction – they are ridiculed. A real author, the logic goes, having moved on to writing their own books, doesn’t look back.

“Here’s the thing,” Naomi Novik explains over the phone from New York. She is the bestselling author of the Temeraire books, a fantasy series that adds dragons to the Napoleonic Wars, and Spinning Silver, which riffs on Rumpelstiltskin. “I don’t actually draw any line between my fanfiction work and my professional work – except that I only write the fanfiction stuff for love.”

In between writing her novels – or indeed during, as she admits that fanfiction is one of her favourite procrastination techniques – Novik is an active member of the fanfiction community. She is a co-founder of the Archive of Our Own (AO3), one of the most popular hosting websites, and a prolific writer in the universes of Harry Potter, Game of Thrones, Merlin and many more.

And she’s not the only professional at work. Rainbow Rowell, the bestselling author of Eleanor and Park and other novels, once told the Bookseller that between two novels, she wrote a 30,000-word Harry Potter fanfiction. “It’s Harry and Draco as a couple who have been married for many years, and they’re raising Harry’s kids,” she said. “It’s them dealing with attachment parenting and step-parents and all these middle-aged issues.”

The divide between a fanfiction writer and an original fiction writer can look very arbitrary when looking at authors such as Michael Chabon, who once described his own novel Moonglow as “a Gravity’s Rainbow fanfic”. Or Madeline Miller, whose Orange-prize winning The Song of Achilles detailed the romantic relationship between Achilles and Patroclus, and whose latest novel Circe picks up on the witch who seduces Odysseus in the Odyssey. Miller said she was initially worried when one ex-boyfriend described her work as “Homeric fanfiction” but has since embraced her love of adapting and playing with Greek mythology. The tag could also be applied to classics such as Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea, reworkings of Shakespeare by the likes of Margaret Atwood and Edward St Aubyn in the Hogarth series, and a spate of parodies: Pride and Prejudice and Zombies, or Android Karenina.

What separates these works from the Harry Potter fanfiction you find online may come down to snobbery. There is an undercurrent of misogyny in mainstream criticism of fanfiction, which is widely accepted to be dominated by women; one census of 10,500 AO3 users found that 80% of the users identified as female, with more users identified as genderqueer (6%) than male (4%). Novik has spent a good deal of time fighting against fanfiction’s stigma because she feels it is “an attack on women’s writing, specifically an attack on young women’s writing and the kind of stories that young women like to tell”. Which is not to say that young women only want to write about romance: “I think,” Novik says, “that [the popularity of fanfiction amongst women is] not unconnected to the lack of young women protagonists who are not romantic interests.”

Others may find it odd that published authors would bother writing fanfiction alongside or between their professional work. But it’s all too simple to draw lines between two forms of writing that, in their separate ways, can be both productive and joyful. Neil Gaiman once wrote that the most important question an author can ask is: “What if?” Fanfiction takes this to the next level. What if King Arthur was gay? What if Voldemort won? What if Ned Stark escaped?

“I believe that all art, if it’s any good, is in dialogue with other art,” Novik says. “Fanfiction feels to me like a more intimate conversation. It’s a conversation where you need the reader to really have a lot of detail at their fingertips.”

For writers still wobbling on training wheels, fanfiction offers benefits: the immediate gratification of sharing writing without navigating publishers; passionate readers who are already interested in the characters, and a collegial stream of feedback from fellow writers.

“There was an audience of people who wanted to read my writing,” says young adult author Sarah Rees Brennan, who wrote Harry Potter fanfiction in her teens and twenties before she published her own novels, the latest of which, In Other Lands, was a Hugo award finalist. “Here were all these people online who wanted stories about familiar characters. Audiences were pre-invested and waiting.”

For writers, whether already published or on the path to being published, this instantaneous readership functions as a writer’s workshop: Novik calls it a “community of your peers”. Spending hours thrashing out the details of Draco Malfoy’s inner life can’t help but function as a crash course in character motivation. And the limits and constraints of working within a pre-existing world, with its own characters and settings, is a unique challenge.

“Fanfiction is a great incubator for writers,” Novik says. “The more constraints you have on you at the beginning, the better. It’s why people do writing exercises, or play scales. That kind of constraint forces you to practice certain skills, and then at a certain point you have the control to bring out the whole toolbox.”

Once some writers get those tools, they never look back. Rees Brennan no longer writes fanfiction. “I had a friend say it’s like the difference between babysitting kids and having children of your own,” she says. “With a world you built yourself, and characters you built, there’s this sense of deep, overwhelming love.”

But Rees Brennan is still a fan of collaborative writing and shared universes, as in the short stories she writes with Cassandra Clare about characters from Clare’s Mortal Instruments universe. “It’s amazing to gather around a kitchen table and yell at each other excitedly about what’s going to happen to mutually beloved characters,” she says. “I want that for every creative person – a chance to find their imaginative family, wherever it may be.”

Novik scorns the idea that published authors should turn their back on fanfiction. She recalls being on a panel where one member said he couldn’t understand why someone would waste their time writing it over an original work: “I said, ‘Have you ever played an instrument?’ He was like, ‘Yeah, I play piano’. I said, ‘So, do you compose all your own music?’”

“When I was first published, I deliberately went to my editors and said, ‘Yes, I’ve been writing fanfiction for 10 years. I love it.’ It was non-negotiable for me. As soon as you do that, by the way, it turns out that like half of the publishing industry has read or been involved in fanfiction,” she laughs. “Shockingly! It’s amazing how all these women who like storytelling have some connection to the community.”

For Novik and many other writers, fanfiction is a fundamental a way of expressing oneself, of teasing out new ideas and finding a joyous way to engage with writing again after the hard slog of editing a novel. The journey to become a published writer isn’t a straight line; it’s a spiral, as we grow older and continue to explore the characters and tropes we love. There’s so many stories waiting to be told – perhaps one or two of them could involve getting Captain America laid. God knows he needs it.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

landfall

On a bright fateful morn, Jack Sparrow brings rumors of the Black Pearl and her crew of the damned to Port Royal. In theory, the ship should be no match for the dragon Tempest and his Captain Norrington — but the Pearl harbors a dangerous shadow and a wicked ally of their own.

or: potc, but temeraire, multi-chapter wip. sequel to windfall

“Well, well. Jack Sparrow, isn't it?”

Norrington flicks his eyes up. Sparrow pulls his hand free and cradles it to his chest. “Captain Jack Sparrow, if you please.”

“I don’t see your ship, Captain,” Norrington says, and looks about the harbor for dramatic effect.

“Perhaps I’ve got one of these dreadful beasties all for meself, lying just around the cliffs here.”

He gestures to Tempest, who sets his ears back, affronted and hissing.

“No respectable dragon would ever ride with pirates,” Tempest insists.

“Ah,” Sparrow says, smiling sourly, “but they would. Just because you’ve never encountered something doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist, savvy? Like the Black Pearl,” with a nod at Murtogg and Mullroy, who pale at the acknowledgement. Sparrow continues, smug, “It’s like what all your charts say — here there be monsters, ‘nd all that.”

Murtogg puts in, “The original Latin phrase translates to Here be dragons, actually, so it’s even more appropriate.”

Mullroy elbows Murtogg to shut up. Sparrow pipes up, “Thank you kindly! Your man has a point, Captain. You never know what lies beyond the edge of the map.”

Norrington narrows his eyes. Sparrow is rather insistent on this point, and even raises his eyebrows at Norrington, waiting for someone to ask a question. Norrington says instead, “Enough hearsay. Captain Gillette, I believe this man falls under your purview.”

(read on ao3 here!)

#pirates of the caribbean#james norrington#*fic#james and the giant lizard#1734's hottest single dad is BACK#h-here we go 🥲#hopefully these ALL won't take three months to write#(who am i kidding. of course they will)

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cisco and the Loyal Dragon

HAPPY BIRTHDAY @hedgiwithapen! if you’ve been reading my little flash/temeraire crossover thing and are expecting more fluff, you might want to brace yourselves because this falls a little more on the angsty side. it’s still cisco and a very protective dragon however, so if that’s what you came for then you’ll like this.

If you’d told Cisco Ramon five years ago that one day he’d be making the rounds of every butcher in Central City buying them out of ground turkey, he’d have laughed in your face. Nobody liked turkey, which was why people only ate in once a year. It was dry and gross and it cooked weirdly, and only weird people ate it if given the choice to eat something else.

It was also, as it happened, the cheapest type of meat to buy, barring undesirable cuts of chicken. So if you needed enormous quantities of raw meat on the regular but didn’t have the money to slaughter a cow every week, ground turkey was the way to go. Not for the first time Cisco wondered how this had become his life as he paid for the seventeen and a half pounds of ground turkey that was all the butcher had left at the end of the day. He’d already hit up every other butcher in the city, so this was his last stop.

“What do you need all this for?” asked the woman on the other side of the counter, who looked like she could break Cisco in half without much trouble.

“I’m one of those people that likes to spoil their pets,” Cisco told her honestly. He did not mention that he had only one pet, that it was more like he was her pet, and that she happened to be a dragon.

The woman gave him an understanding smile and Cisco tried not to imagine the collection of vicious dogs he suspected she was picturing, perhaps somewhat reminiscent of her own. He walked out of the shop, laden with turkey and thinking about what he’d recently read about Chinese dragons eating cooked meat rather than raw. He wondered how he would theoretically cook this much turkey without it drying out, his brain immediately beginning to construct a device similar to the revamped slow cooker he’d constructed for his mother, and he only dimly noticed the unmarked black van parked directly outside.

He noticed it more however when the side door slid open and four men in full combat gear leaped out. Instinctively Cisco dropped the turkey and put up his hands, but this turned out to be the wrong thing to do. Immediately two of them grabbed him, kicking his legs out from under him and dragging him toward the van. Cisco yelled, but there was no one nearby, and he found himself hoisted inside by strong hands, unable to even struggle to free himself. He yelled again even as the door slid shut behind them, but then there was a crackle of electricity and a searing pain in his side.

The last thing he saw before he blacked out was the word “Army” on the chestplate of one of his attackers.

***

One of the things that Gussie was thankful for was that Cisco was not generally given to being late.

Cisco liked being at the lab. He loved working, he loved the people he worked with, and he loved spending time with Gussie. The lab was literally his favorite place to be. He did not stay away for long periods of time if he could help it. He did not come in late. And he certainly did not do either of those things without telling someone.

“Where is he?” Gussie asked no on in particular as she paced agitatedly around the cortex.

“He’s usually here by the time I leave on patrol,” Barry said, sounding somewhat concerned himself. He was already in his Flash suit, but he was waiting on Cisco before going out.

“He’s not answering his phone,” Caitlin said, holding up her own phone demonstratively. If Gussie squinted she could see a lot of outgoing text messages, but none in response.

“I’m going looking,” Gussie announced, striding purposefully towards the door.

“Bad idea,” Barry was suddenly standing in her path. “Remember what happened last time you went off looking for Cisco?”

“Yes,” said Gussie. “I found him.”

“You found Iris,” Barry corrected, “who still hasn’t forgiven me for lying.”

“That,” Gussie snapped, “is your problem.”

She made to go around Barry, but he was suddenly in her way again. She tried to go the other way, but once more she found him directly in front of her.

“Barry’s right,” Dr. Wells piped up, drawing Gussie’s attention off Barry and onto him. “We don’t even know that anything’s wrong, and it’s not yet fully dark. The last thing we need is more blogs like Miss West’s talking about sightings of dragons.”

“I do not care,” Gussie’s tail lashed. “I want to find Cisco.”

“I may be able to help with that,” said a voice from the doorway.

All three of them turned, to find a man dressed in an army uniform standing just outside the entrance to the cortex. Immediately Barry’s mask was on and he was racing to place himself between the soldier and the rest of the room’s occupants, and Gussie dropped into a crouch, preparing to spring at the man if he threatened anyone.

“I presume General Eiling sent you,” guessed Dr. Wells, turning his wheelchair to face the newcomer. “What information do you have about Mr. Ramon?”

“I can take you to him,” said the soldier, not looking at Dr. Wells or at Barry, but rather at Gussie over Barry’s shoulder. “But this offer is one time only, and only for the dragon.”

“You’re nuts if you think-” Barry began.

“Deal,” said Gussie, without hesitation.

The soldier nodded, turned, and marched off down the hallway.

“Gussie you can’t!” called Caitlin, getting hurriedly up and running after Gussie as she took off after the soldier.

“I am going to find Cisco,” Gussie said. She did not see why Caitlin seemed so upset. “I will bring him back here, and everything will be alright again.”

“You honestly think they’re just going to let you?” Barry easily kept pace with her as Caitlin began to fall behind. “You think-”

“I know they will let me, because I am much bigger than them and can breathe fire,” Gussie explained patiently. “They will not have a choice.”

“I’m coming with you,” Barry insisted.

“The offer only stands if we go alone,” the soldier said over his shoulder.

“Stay here,” Gussie ordered Barry. “I will get Cisco, and we will be back soon.”

***

Gussie flew behind the soldier’s car as he led her out of the city. It was not yet entirely dark, so Gussie could keep track of the car even at the height she had to maintain to not be seen. She had very keen eyes, which Cisco said came of having ancestors that lived on mountains and had to see human bandits coming from a long ways away. Sometimes the man changed direction unexpectedly, and sometimes he even went back the way he had come, but eventually they made it out of the buildings and into the forest.

It was harder to track the car through the forest, with its dense trees, but there was only one road to follow, and that was where the trees were thinnest. She followed the road all the way to a wall, which surrounded a collection of small, squat, ugly buildings. A gate in the wall opened to admit the car, but Gussie simply flew over the wall and landed in an open space just past the gate.

“Where is Cisco?” she demanded immediately, as the soldier stepped out of his car.

“All in good time,” said a voice Gussie had not heard before. She turned, to see an older looking man with greying hair and deep wrinkles on his face. He was dressed like the soldier who had brought her there, but the soldier stood at attention when he approached.

“Who are you?” Gussie asked as the man approached her, tail lashing. “Where is Cisco?”

“I’m General Wade Eiling,” the man introduced himself, “and your friend Cisco is inside. I’ll bring him to you, once I’m certain you understand your position.”

“You should understand your position,” Gussie hissed angrily. “I am very big and I can breathe fire. You should give me what I want.”

Eiling, of all things, chuckled. “I thought you’d say that.”

Suddenly, from everywhere at once, there came a horrible piercing scream. Gussie flinched, knowing Cisco’s voice when she heard it, but she could not tell where it was coming from.

“Cisco!” she called, turning circles as she tried to pinpoint the source of the screaming. “Cisco, where-”

The screaming stopped, and Gussie whirled to face Eiling.

“Where is he!” she snapped. “If you have hurt him-”

“I have hurt him,” Eiling admitted, surprisingly her, “and I’ll hurt him again. Over and over until you understand your place, monster.”

“I’m not a monster,” Gussie said, “I’m a marvel, and you-”

The scream came again, louder and more pained than before.

“Cisco?” Gussie screeched, turning this way and that as she tried to tell where it was coming from. “Cisco, I am coming, I am-”

“You are not in any position to correct me,” Eiling interrupted once the screaming had stopped. “I can hurt your precious Cisco as much and as often as I like, and the only way you can stop me is by doing what I say.”

“Where is he?” Gussie asked. Asked, rather than demanded, because as much as she did not want to admit it, she was afraid. She was afraid for Cisco, and what it was that was making him scream. She did not want to hear the sound of Cisco screaming every again.

Eiling smiled, cold and cruel, then held up a small black box to his mouth. “Bring him out.”

The door to the building behind Eiling opened, and out came a trio of soldiers. In the center of the group was Cisco, one of them holding each of his arm and the third one walking slightly in front of the other two. His stumbled as they dragged him outside into the open space, coming to a stop a few paces behind Eiling.

“Gussie!” Cisco said in surprise when he saw her.

“Let him go!” Gussie howled. “Let go of him, you-”

“Shut up!” Eiling shouted, at a surprising volume for something of his size.

The soldier who had been at the front of the procession turned around. He looked at Eiling, and when Eiling nodded the soldier drew back his hand and punched Cisco with what looked like a considerable amount of force. Gussie screeched but stayed in place, not daring to breathe fire at the soldier for fear of hitting Cisco too.

“Will you do what I say?” Eiling asked. Cisco shook his head at Gussie, eyes wide.

“No!” Gussie snapped petulantly.

Eiling nodded to the soldier again, and he drew back his other hand and hit Cisco again.

“Stop!” Gussie’s feathers were fluffed up as high as they would go.

“Will you do what I say?” Eiling asked, louder this time.

“Never!” Gussie flared her ruff at him, but Eiling did not back down.

This time the soldier took something from his belt, and when he placed it against Cisco’s neck Cisco screamed again.

“Stop it!” Gussie clawed at ground but did not attack, still afraid of hurting Cisco. “Stop it, stop it!”

“Will you do what I say!” Eiling shouted.

“No!” Gussie insisted, “I will not, I will-”

The soldier pulled his gun from its harness and pointed it at Cisco’s head. Cisco stared down the barrel of the gun and swallowed, then looked at Gussie and shook his head again. No.

“Will you do what I say?” Eiling asked, voice quiet and deadly calm.

Gussie hesitated a moment, looking into Cisco’s fearful, pleading eyes. There was only one possible answer.

“Yes.”

***

Gussie was not back soon.

They waiting for over an hour, but Gussie did not return and no one received a call or text from Cisco. At Dr. Wells’ insistence Barry went out of patrol, but nothing could take his mind off his missing friend. This would be the second time Cisco had been kidnapped and Barry hadn’t been able to do anything, hadn’t even tried to do anything, to save him. He couldn’t help but feel like a horrible superhero, and a horrible friend.

“Any sign of them?” Barry asked once he had come to a stop in the cortex.

“Not yet,” Caitlin shook her head.

Barry stripped off his suit and changed back into normal clothes in the blink of an eye. “What about the news, any word about a fire breathing dragon going on a rampage?”

“The news networks and blogosphere are all quiet,” Dr. Wells told him.

“You know,” said Caitlin suddenly, “Gussie does have a tracker in her collar.”

“Is it active?” Barry demanded, racing over to stand next to Caitlin. “Where is it?”

Caitlin tapped at her tablet a few times, then turned it to display a map of Central City. The map zoomed in on the forest to the west of the city, until a collection of buildings surrounded by a thick wall came into focus.

“There’s an army base just outside the city,” Caitlin told him. “The tracker’s sigal is coming from in there.”

“Perhaps we should-” Dr. Wells began, but Barry was back in his Flash suit and out the door before he could finish.

***

The army base was surprisingly easy to get into. The gate was open when he arrived, no guards stationed on the wall spotted him, and there did not seem to be anyone in the courtyard created by buildings on three sides and the gate on the fourth. Everything was quiet, and under cover of darkness Barry stopped and wondered which of the three buildings to look in first. The central building seemed to be the biggest, probably the place where Eiling might hide a captive dragon, and the massive front door was ajar. It was almost too easy.

Exactly why it was too easy became apparent when the courtyard was flooded with light.

“Hello Flash,” said Eiling, stepping out of the shadows to stand squarely in Barry’s path. “Fancy meeting you here.”

“Barry get out of there,” came Dr. Wells’ voice in his earpiece.

“Where are Cisco and Gussie?” Barry demanded, ignoring Dr. Wells to focus on Eiling.

Eiling signaled to someone behind him. “Let out the beast,” he barked.

From the shadows of the open doorway to the central building, out stepped Gussie. Her wings drooped, her feathers were flattened to her skin, and her head hung down as though in shame. She was not wearing the collar Cisco had made her, but rather a heavy black harness that looked to be made of kevlar.

“Gussie,” Barry called urgently, “let’s get out of here! We’ll find Cisco-”

“Fire!” shouted Eiling.

Gussie opened her mouth and let forth a jet of flames. Barry just barely made it out of the way without getting scorched, and she followed him with the fire until he was backed into a corner of the courtyard.

“Gussie!” Barry cried frantically. “It’s me! I’ve come to help you-”

“You can’t help,” said Gussie shakily, “I have to do what he says.”

“No you don’t!” Barry argued.

“Fire!” Eiling shouted again.

Gussie inhaled deeply and then fire was pouring once again from her mouth. Barry ran in the opposite direction this time, and thankfully by the time he reached the opposite corner she was out of breath.

“Gussie, why?” Barry asked plaintively.

“Because he’ll hurt Cisco if I don’t,” Gussie groaned pitifully. “You don’t know . . . you don’t know . . .”

“Fire!”

***

“Barry’s vitals are dropping,” Caitlin announced, bent over her workstation. “I think he was hit.”

“Caitlin,” said Dr. Wells calmly, “would you be so kind as to take a van and get as close to the base as you can? I think Barry made need a ride home after this.”

“But-” Caitlin started to protest.

“I’ll handle things here,” Dr. Wells assured her.

Thus mollified, Caitlin turned and left the cortex at a run, leaving Dr. Wells alone at the comms.

***

The comms were fried.

Everything was fried.

Barry could feel his bare chest knitting itself painfully back together, but nothing could repair the damage to the front of his suit. Gussie’s fire was hot enough to melt titanium, and certainly hot enough to burn away even Cisco’s reinforced tripolymer fabric. He struggled to sit up, but suddenly he felt hot breath wash over his face.

“I’m sorry,” said Gussie as she positioned herself over Barry, pinning him down. “But they will hurt Cisco.”

“I understand,” Barry said hoarsely. “You have . . . . to protect . . . “

“Finish him!” Eiling commanded.

“No!” Gussie howled, looking over her shoulder at Eiling.

Eiling lifted a radio to his mouth and said, “Bring him out.”

There was a sound of something being struck and then a punctuated cry, and Cisco stumbled out from around the corner of the central building. His hands were bound behind him, and he was flanked by two soldiers carrying assault rifles. He had a black eye, a split lip, and what looked like an electrical burn on his neck.

“Cisco!” Barry yelled.

“Cisco!” Gussie howled.

“Enough!” Eiling barked. “Finish him, or Ramon dies!”

One of the soldiers raised his gun and pointed it at Cisco’s head. Gussie turned back to Barry. Barry closed his eyes.

In hindsight Barry wished he had not closed his eyes, because then he might have understood what happened next better. There was a whooshing sound to his right, a cry of alarm from the direction of the soldiers, and then Cisco’s voice above him screaming for Gussie to stop. His eyes popped open to see Cisco standing beside Gussie, his arms thrown around her neck, face pale and sobbing into her feathers.

“What . . .” Barry began in bewilderment, but he was ignored.

It took Gussie a moment to realize what had happened. That Cisco was no longer with the soldiers, a gun to his head, and that he was instead beside her. Once she did realize it however she rammed her nose into Cisco’s stomach, crooning joyfully and nuzzling him fiercely.

“Cisco!” she managed, in between wordless noises of affection.

“I’m ok!” Cisco said, over and over. “I’m ok, I’m ok, I’m-”

Suddenly Gussie wrenched away from him, one foreclaw pushing him toward Barry. Cisco looked stunned for a few seconds, until Gussie turned to face Eiling.

“Gussie no,” said Cisco, face pale and horrified. “Gussie stop, Gussie-”

Gussie did not respond to him. She spread her wings and leaped, gliding the distance between where she had been standing and where Eiling was now backing towards the open doorway in alarm. Cisco shouted for her to come back, and Eiling screamed for her to stand down, but Gussie had decided on her next course of action and she would not be dissuaded.

It was oddly quiet in the courtyard as Eiling’s first scream split the still night air. His second scream was a bit gurgly, owing to the fact that Gussie’s front claws were embedded in his lungs. His third strangled, soft scream was cut abruptly short as Gussie bit into his neck, and that was the last sound General Wade Eiling ever made. His body made a few more noises, sickening squelches and visceral tearing sounds as it was reduced to its component parts by sharp talons. In the end though, when Gussie was through, there was silence.

***

They’d had a hell of a time cleaning Gussie off.

Eventually they’d had to just take her down to the parking garage and spray her down with the hose. It dislodged a few feathers, but there was no other way to get all of the blood off of her before she went upstairs. There was simply no getting all of it off the roof where she’d landed, and the hallway where she’d tried to come inside would have to be power washed as well, but eventually they got her clean enough for Cisco’s lab.

Caitlin treated what wounds Cisco had and checked him over for further injuries, of which there were none. Cisco did not say anything about going home, and Gussie did not mention it either. Barry also didn’t want to go home, and in the end only Dr. Wells returned to his own house for the evening. Iris and Joe were called to spend the night as well, and Gussie slept soundly with all of them cuddled against her side. Cisco lay with her head in his lap, and when she awoke during the night with a mournful croon he scratched at her feathers until she could lay her head down again.

The next day people had to go to work however, so Joe and Iris and Barry had to leave. Caitlin went back to her own lab, to her own work and her own projects, and Gussie and Cisco stayed in the workshop. Cisco tried to work on his machines, but his hands were shaking a bit too much, and in the end he and Gussie ended up watching an old Charlie Chaplin film projected on the wall.

“Why is this funny?” Gussie asked, despite the fact that she was laughing also.

“Timing,” Cisco said simply, wiping tears from his eyes. “It’s all about timing.”

Gussie nuzzled him affectionately, then laid her head in his lap. She could only watch the film out of one eye like this, but that was alright.

“Gussie?” Cisco asked, voice quiet.

“Yes?” she replied, just as quietly.

“You shouldn’t have attacked Barry,” he said.

“Eiling would have killed you if I had not done it,” Gussie told him, knowing the truth of it deep in her bones. “I could not have let him hurt you.”

“You can’t hurt people just because-” Cisco began, but Gussie cut him off.

“Yes I can,” she said firmly. “If it will keep you safe I will burn this city to the ground. You may tell me not to if you like, but I will not obey you if it puts your life at risk.”

There was a pause where Cisco did not say anything, and Gussie waited nervously for his reply. Then his hand came up to stroke the feathers on top of her head.

“I know,” he admitted, “and I know that’s in your nature, but I have to at least try to stop you.”

“You have tried,” said Gussie, as though humoring him. “If you want to stop me from hurting people to protect you, then I suggest you stop being kidnapped.”

“I’ll try,” Cisco said, and it came out somewhere between a laugh and a sigh.

“Good,” Gussie concluded, then closed her eyes and nuzzled into Cisco’s belly.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

I have read, watched, and listened to a vast number of stories in my life. I have been devouring books since I was old enough to understand my parents reading them to me. I have binged my way through dozens of TV shows. I have seen more films and plays than I can possibly count or remember. In recent years, I discovered podcasts and added a handful of them to my diet of stories as well. If I pictured the vast collection of every story I have ever consumed in my life as a massive library, there would probably be only a single, relatively small shelf, high up at the back, that contains a collection of media that I have FELT change me - as a storyteller, and also probably as a person. Every story has an effect, of course, but there are a few that have caused a sort of tectonic shift, noticeable before I'd even finished the story. There are a few that transcend the typical boundaries of storytelling to become something more than what they are. Lord of the Rings is up there. I think Bleak House by Charles Dickens is up there. Shakespeare's body of work as a whole is probably in the center of the shelf. There are many stories I love dearly, that mean something very special to me, but aren't quite THAT kind of story, not for me. Harry Potter occupies a very special and very important place in my life, but I don't think it's on that shelf. Neither are the Disney films I cherished as a child, although that may be only because I can't remember watching them the first time. Fullmetal Alchemist: Brotherhood is there. So is Avatar: The Last Airbender. So, I think, is Gravity Falls. They are stories that make me want to be better, to do better, especially as a writer and an actor. They make me reconsider the way I tell stories and the way I bring them to the people around me. Every story does that - if only to say, "I hated that and I never want to put it in my own writing" - but there's something almost unquantifiable about the way these stories touch and shape me. I can't explain it, only that THESE are what I go back to when I need a reminder of the way that stories should be told. These remind me of everything I aspire to do. The Book Thief by Markus Zusak is up there. Neverwhere by Neil Gaiman is there, next to at least one of Terry Pratchett's Discworld novels. A performance of Hamlet I saw at the American Shakespeare Center is represented by a program or a ticket, as is a production of Taming of the Shrew at the Globe, and a production of Arcadia I saw in New York some years back. And honestly, while I'm probably forgetting a couple things, that's... pretty close to all of it. For all the many stories I have heard in my life, not many have hit me this way. If they had, it wouldn't be as significant. The shelves around it are occupied by all sorts of stories that hold extraordinary importance to me, for one reason or another. Harry Potter, Mulan and the Lion King and the Little Mermaid, Steven Universe, Rick Riordan's books, Sense8, the rest of Dickens' and Pratchett's and Gaiman's books, Moonlight, A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius by Dave Eggers, Welcome to Night Vale, the Temeraire series, Homer's Iliad and Odyssey and Aeschylus's Oresteia, a book called Mara: Daughter of the Nile... this list could stretch out for miles. But it comes down to this idea of the stories I go back to - not for comfort or love or appreciation, because that's everything I just listed, but for INSPIRATION. To be reminded of just how deeply a story can move me. I can't make this judgement for sure just yet. I have to wait, and recover a bit emotionally from the finale, and see where I land when I can look at it with clear eyes. But The Adventure Zone FEELS like one of these stories that changes me. It feels like the kind of story that leaves me a better person than it found me. It makes me want to just sit quietly and watch the world for a while, because the journey it took me on mattered. I feel INSPIRED, so much so that I almost want to write the McElroys a thank you note for giving us this show. Perhaps I'm being overdramatic. Perhaps with a day or two of emotional recovery TAZ will join the giant bookcase of stories I love and cherish, but no more. But the feeling I got listening to the closing music is the same feeling I got closing Neverwhere the first time, or watching the credits roll on the last episode of Avatar. This show was something DIFFERENT than normal. Something that mattered tremendously. And I am so, so grateful that it exists.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Being Mortal | When Breath Becomes Air | How We Die

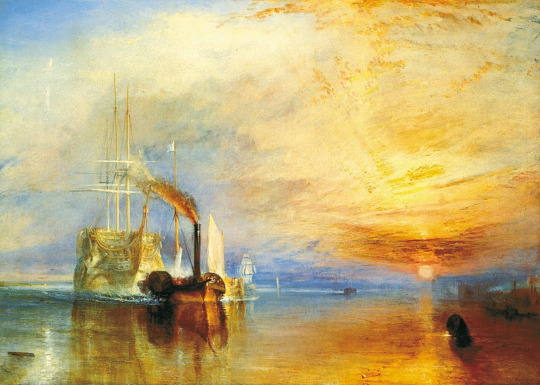

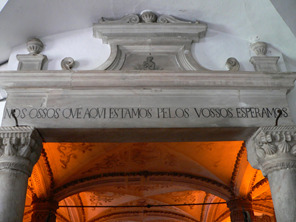

The Fighting Temeraire - J.M.W. Turner

Introduction

Prelude III: Mortality – Santiago Wu

At the break of dawn begins a new day,

Now I am one with the world,

To be part of something greater, I pray.

All of us part of the same mystery unfurled.

Time past and time future,

Everything that came before,

To everything that follows.

All my love to long ago,

And my hopes for days to come.

Heart selfless, soul mindful.

Live, laugh, love —this the meaning of life?

My candle burns at both ends.

All the places I’ll never see,

All the people I’ll never know.

This might be how it ends.

Memento Mori - Remember that you have to die.

Vanitas – Philippe de Champaigne

Death is inextricably entwined with life, hidden in the shadows patiently waiting to take us on the day we take our last breath.

Reading the accounts of dying men and women is truly humbling, whether it be in their twilight years or prematurely - death comes for all of us. All their stories and memories of human life and emotion: all the joy, love, laughter, tragedy, sorrow and regret willing us all to live more fulfilling, meaningful lives.

If I were a writer of books, I would compile a register, with a comment, of the various deaths of men: he who should teach men to die would at the same time teach them to live.

That to Study Philosophy is to Learn to Die – Michel de Montaigne

I think you always know the moment when you finish a book whilst digesting the last words and the text as a whole, its impact and importance in your personal life. The books I am writing about all discuss mortality – a taboo topic normally hushed about and swept underneath carpets. To read and understand the writings of these books in such a raw and honest fashion was a welcome albeit overwhelming change in gear. These books have had a massive impact personally and have formed an epoch in my life and attitudes to life and death. Being Mortal by Atul Gawande When Breath Becomes Air by Paul Kalanithi and How We Die by Sherwin Nuland are books which have the rare privilege of being read more than once, truly understood, annotated to grasp every fragment of detail of wisdom shared in their pages. The authors are doctors (American surgeons, all sons of immigrants). These men had the privilege and the burden of looking after and treating people with fatal illness in their daily practice. Their accounts are beautifully written, one from the perspective of a doctor looking after patients in their end of life and the other written as a patient facing his own death and one written in his twilight years recounting his medical practice and patients and sickness and death. I have heavily quoted all three books because I believe they offer profound wisdom which is literally life-affirming, in fact I have written this for myself as much as my reader in order to truly understand the essence of the lessons of what these three books and their themes can teach us.

I was first introduced to Atul Gawande from the 2014 Reith Lectures on BBC Radio 4 which were a series of four excellently given speeches on life, death and medicine. His deep research on medicine for the dying draws upon many different threads with a surgical precision. His striving to be better and to constantly improve is remarkable and sets a paragon of medical practice. I was humbled by his admissions and failures and his striving to be a better surgeon. The lectures provided a grounding to my burgeoning clinical experience and taught me to never take anything for granted – never to be complacent of my abilities because to have another human being’s life in your hands is a huge privilege which some say is playing god with a small ‘g’. He understands the fine line between offering false hope and deciding when to cut your losses which is never a clear choice. I immediately related to Paul Kalanithi’s love of literature. It is rare in medicine to meet someone who loves literature so much – stories of humanity, emotions ranging from highest peak to lowest ebb… I can tell this deep affection directly influenced his writing and indeed his medicine and approach to life. What made him unique was his relentless quest to search for life’s meaning. With his juggling of both art and science, I immediately remembered my own decision for choosing to enter medicine. Art reflects the universe whilst science explains it. Medicine married the two together. Though in modern medicine, science is king – like Paul Kalanithi, I have a strong affection for my first love of literature which I’ve come to realise expresses and sometimes even explains the universe in better ways than science can. Sherwin Nuland’s ground-breaking book How We Die has been mentioned in circles of medical humanities and referenced by Atul Gawande as the quintessential book on the medical viewpoint of death and mortality. It is easy to see why this book, though nearly thirty years old is still as relevant as ever today. The art of medicine has been revolutionised and become more efficient by multiple progressions and innovations in science and technology but at its heart remains the doctor-patient relationship which Sherwin Nuland writes about in a philosophical and humane way. He marries both medical science and the stories of his patients which from a medical point of view was an utter joy to read. Funny how things have changed since 1994 when Sherwin Nuland wrote his book and also how much they remain the same – sobering to know how despite our scientific and technological advances in medicine, our attitude towards death and dying patients is still primitive and myopic. In How We Die, Sherwin Nuland details the most common causes of death in the developed countries: cardiovascular disease, old age, stroke, infection, murder, HIV/AIDS, cancer in individual chapters with case studies based on his own patients or his family members.

The theme of death and mortality explored in these books led me to think a lot about them especially in my early medical career. When I first started this blog, I wrote of great figures in human history that have sadly left us and their medical conditions. From a great fighter to an entrepreneur to a musician, all were unique human beings with different qualities but what united all of them – and also us, is death. Death is something that is often misconstrued in our modern lives, whether we euphemise, sugar-coat or indeed fear it. The old saying of De mortuis nil nisi bonum or ‘Do not speak ill of the dead’ and Requiescat in pace or ‘Rest in Peace’ pervades our lives even today. We feel sadness when great figures die because of the finality of death – there is no return, we will never know what would have come next. We are reminded of our own lives and within our limited time we too are able to achieve something great. Of course, it is foolish to be able to condense every reference and understand them completely, that will take more than a lifetime to study, a Sisyphean task – death and ars moriendi (the art of dying) being perhaps the biggest and most universal theme of human life across all cultures. There are still works by Heidegger, Nietzsche, the Bible, the Tibetan Book of the Dead, I Ching, the Mahabharata, the Vedas, the Quran, countless poets, novelists, philosophers, scientists etc. that I haven't been able to read in this time, this of course is a study over generations upon generations who still are uncertain about the question of death. I cannot answer these questions death poses, there are mountains upon mountains I will need to ascend in order to catch the slightest glimpse of an understanding. I myself cannot even expect to offer the slightest bit of eloquence of my own voice – I elect instead to let great men and women do that for me for may I learn from them and one day pass on this knowledge. After spending the past year contemplating on death and mortality and reading around the topics from great accounts by humanity, I am certain that what this teaches us is the appreciation of life now in the present. None of us knows when we will die, only we know for certain that we will die. In our cycles of time, this is our time on Earth, our time to live. How we come to peace with death and our mortality is focus of these books I have mentioned and the lessons we can all learn from them.

As I child, I had devoured the Roald Dahl books like any other kid in school I loved his dark wit and unpatronizing creativity in his novels where they provided the first forays into my love for books and imagination. One thing always struck me in his books that I never truly understood until my youth, was his motto that preceded each and every one of his novels. I had a much loved, battered double copy of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory & Charlie and the Great Glass Elevator which I had read several times over. The motto that perplexed me well throughout my childhood was:

My candle burns at both ends

it will not last the night.

But oh my foes and ah my friends,

it gives a lovely light!

How apt of Roald Dahl! Even in children's novels he never hid death from them – didn't the twits shrink away into nothingness and didn't James' parents get squashed by a rhinoceros? It's a beautiful motto, the transience and beauty of life condensed into four lines. When I look back over my life, over petty arguments, being let down and hurt by others, showing loved ones my worst side – I am deeply humbled. Life is short, I don't want it to be marred by acrimony and bitterness and regret. Those are the things that don't matter, the bitter pill you stow away at the back of the mind to learn a cruel lesson from and yet cringe at who you could be and hopefully were. There isn't room for such sourness, when you read the accounts of the dying – there is often the bittersweet feeling of regret and missed opportunity as seen in Top Five Regrets of the Dying by Bronnie Ware, a palliative care nurse.

https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2012/feb/01/top-five-regrets-of-the-dying

Here we must focus on the important things – the old sayings of ‘letting the little things go’, and ‘don’t sweat the small stuff’ are true. Do we hold a grudge to everybody who has wronged us? If that’s the case then we’d only hold a grudge to everybody because as Bob Marley said “The truth is everyone is going to hurt you. You just got to find the ones suffering for.” Life is too short for all of the pettiness and trivialities. Forgive and love, it’s the best antidote to bitterness and the best steps to self-love for through only loving ourselves can we love others.

Wherever your life ends, it is all there. The utility of living consists not in the length of days, but in the use of time; a man may have lived long, and yet lived but a little. Make use of time while it is present with you. It depends upon your will, and not upon the number of days, to have a sufficient length of life. Is it possible you can imagine never to arrive at the place towards which you are continually going? and yet there is no journey but hath its end. And, if company will make it more pleasant or more easy to you, does not all the world go the self-same way?

That to Study Philosophy is to Learn to Die - Michel de Montaigne

The Starry Night - Vincent Van Gogh

Medicine and death

The Doctor – Sir Luke Fildes

“To me, the subject will be more pathetic than any, terrible perhaps, but yet more beautiful.”

Being mortal is about the struggle to cope with the constraints of our biology, with the limits set by genes and cells and flesh and bone. Medical science has given us remarkable power to push against these limits, and the potential value of this power was a central reason I became a doctor. But again and again, I have seen the damage we in medicine do when we fail to acknowledge that such power is finite and always will be.

We’ve been wrong about what our job is in medicine. We think our job is to ensure health and survival. But really it is larger than that. It is to enable well-being. And well-being is about the reasons one wishes to be alive. Those reasons matter not just at the end of life, or when debility comes, but all along the way. Whenever serious sickness or injury strikes and your body or mind breaks down, the vital questions are the same: What is your understanding of the situation and its potential outcomes? What are your fears and what are your hopes? What are the trade-offs you are willing to make and not willing to make? And what is the course of action that best serves this understanding?