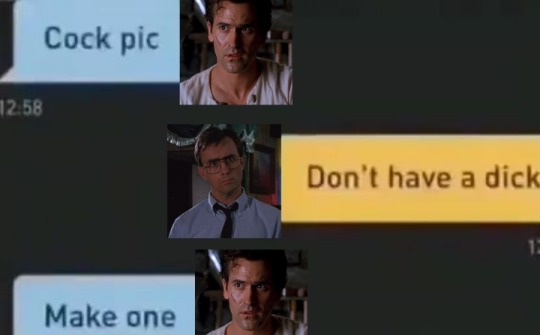

#About both of them

Text

save me ashbert. ashbert. ashbert save me.

#reanimator#re-animator#re animator#reanimator herbert west#herbert west#the evil dead#evil dead#the evil dead 2#ashley joanna williams#ash williams#ashbert#yeah there are some trans headcanons here#about BOTH of them#because they deserve it#BECAUSE I DESERVE IT#i just can't get them out of my head

165 notes

·

View notes

Text

I am so normal about Anthony Lockwood and also Cameron chapman

so normal

*screams into pillow*

so normal

21 notes

·

View notes

Note

Top 5 Scully moments! 💗

off the top of my head <3 you’re getting 8 sorry

(i left off triangle because we already talked about it today but in my heart it truly is top 3)

1/ clyde bruckman’s final repose

when the hotel scene opens on her sitting criss-cross on the bed with playing cards and you just hear her finish up explaining the plot of moby dick to bruckman and connecting it thematically to hamlet…i can hardly contain myself. she was EXPLAINING THE PLOT OF MOBY DICK to the psychic.

and then after all her talk, her shift is over, and before leaving she leans in close and sighs and asks, “alright. so how do i die?” shh don’t tell mulder she asked ❤️

(and his tender answer: “you don’t.” immortality in reciprocated kindness.)

2/ beyond the sea

giving up the chance to know what her father’s last message to her was, and saying that she already knows what he wanted to tell her.

“he was my father.”

she seemed so disappointed and confused in the beginning, when her mother gave that same response (“he was your father”) to her questions of if he was proud of her. it’s not enough evidence, that someone was a father, to really know the things she was doubting.

but in the end, when she tears up and whispers her answer, it’s clear. it’s not that he was a father, and therefore loved and was proud of his children, because that’s what fathers do. he was her father. and she knows how he felt and what he wanted to tell her because she knows him, and she knows the relationship that they had, and she knows how much he loved her.

it’s that kind of implicit understanding that sets her apart, both from mulder and in the world.

(additionally: bursting into boggs’ cell and screaming at him that if mulder dies she will gas him out of this life herself and no one will stop her. she is 5 feet 2 inches of ferocious love.)

3/ memento mori

her letter. god, i make fun of her for it but god does it say so much. she was dying and she was completely alone and she was in that bed every single day writing, writing to him. begging forgiveness, asking for grace, pleading to be seen.

she knows herself so intimately and so completely, and she knows the world she lives in so fully, and she loves it and she loves him so deeply.

she didn’t even want him to read it, it was enough just that it existed, that it was hers and it was real.

4/ detour + william

singing to mulder in the woods, and then years later singing that same song to their baby. she has memorized everything. every moment is so important, so worth passing along.

(“that’s the other thing you’ve given me, mulder, courage…and i hope that’s a gift i can pass on.”)

5/ irresistible

there’s something so resonant and intimate about her fear in this episode. both her lingering fear in the trauma of bearing witness to this kind of brutalization, but also her fear of vulnerability. the way she does everything right, she does everything that you’re supposed to do: she takes a step back, and goes where she’s more useful. she goes to therapy. she handles it herself, like the good captain’s daughter. like she says, it is her job to deal with these things.

she doesn’t just shut down and avoid it, she’s conscious; she’s trying to cope in the way that she’s comfortable.

and it still just isn’t enough. until that moment she says once more that she is fine, and mulder tips her chin so that she has to look at him. and she just breaks down sobbing the moment she sees his face, grabs onto him and weeps into his chest.

she has “always been the strong one,” she did not want him to know that this case was getting to her, but ultimately, there was no way to survive it without facing it.

(thinking of 23+ years later in a motel, the way she creeps into his room and says the case is really bothering her, ducks under his covers.)

6/ ghouli

when the windmill snowglobe, the one thing that she has from her son’s life, breaks outside the hospital. and the person she bumped into (who turns out to have actually been jackson in disguise) apologizes, and she just smiles sweetly and says, “no, it’s my fault. it’s okay.”

she has no idea how important that moment is, she has no idea that this stranger is secretly her baby, noticing the things she’s holding onto from him…and she’s so understanding and gracious in impossible circumstances anyway.

that’s what gives her (and mulder) that miracle moment in the end of the episode, of getting to see jackson. (that’s immortality in reciprocated kindness)

7/ fight the future

my absolute favorite favorite favorite moment of the movie: mulder and scully make it out of the vent. they’re both collapsed on the ground in antarctica. scully has just been revived after she stopped breathing, she’s passing out…and the spaceship comes out of the ice.

and mulder is looking up at the ship with the most joyful heart-melting grin and wonder, and he says “scully. you gotta see this.” (the exact same thing he said 5 years earlier on their second case)

and she whispers, “i see it.”

it’s so special.

and then, bless his heart, mulder’s recently-shot-in-the-head exhausted ass just fully passes out on the spot.

and she sits herself up and grabs him and pulls him over to her and just holds onto him. they’re alive, and she saw it, and she barely has anything left in her at all but she finds enough for both of them.

honorable mention: “shut up, mulder. i’m playing baseball.” <3 girls when they quietly beg the person they love to invest in something “on this planet” and they understand when that first step is being offered to them, they do not need it explained.

it’s so reminiscent of a moment that almost made this list, when mulder gives her the apollo 11 keychain for her birthday, and they’re interrupted before he can tell her why. and in the end, looking up at the stars, she tells him that she thinks she knows. she tells him that this novelty keychain is about “extraordinary moments” and history leaping forward and how you “must dare to dream” and how far perseverance and teamwork can take you but how “no one gets there alone” and remembering sacrifice and achievement.

and he’s just silently staring at her like…like she’s everything and she’s dying and it’s completely unimaginable. like he knows, in that moment.

she sees so much in him, without explanation.

#thanks for the ask i love doing these so much#i love to just ruminate on what i Love and what touches me in this story#i could keep going on and on#about both of them#bc also ‘never again’ obviously and ‘ebe’ and ‘lost art of forehead sweat’ and so many others i took off#there’s so much to her character that is so important to me that i didn’t even touch on here#but that’s a testament to how rich these characters are#asks

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think the reason Jonathan interrupted Mike and Will twice in season 4 was as further, albeit subtle, buildup to that talk at the end of volume 2.

Even if we don't think about it the first time around, those were opportunities for him to notice too.

Notice that there was...something between them. Something was happening, shifting. And as I've said before, he just didn't bring it up because it wasn't his place until he saw that it was *hurting* Will. A theme of this season was not leaving people alone in their grief and depression.

But I am a strong believer in the idea that Jonathan noticed both of them each time. Not just the way Will was looking at Mike but the way they were looking at *each other*, because in those interrupted moments, if anything at all was notable or "counted", there was mutual participation.

As I've said before, Jonathan saw and backed off. On multiple instances dating all the way back to how he looked straight to Will when Mike said he loved El. But he noticed with more confirmation this year. And he held off until he knew Will might need him and not come to him on his own.

But I think that those moments were just more internal buildup in Jonathan of instances for him to notice that something brewing between them. Ammunition, background, context to further confirm and back up his interpretation of Will's speech to Mike in the van.

#jonathan byers#jonathan knows#about both of them#but it's not his place on mike and he knows it#it's barely his place on will#stranger things#byler

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

(about Izzy as tragic character, just a warning)

after drying my tears, I have another complaint: if they really wanted Izzy to be the tragic character (it would still hurt and made people mad probably), for him to die and take the blame on himself and all that, they should commit to this goddammit it. Do it properly like s2e1&2. If they haven't really reconcile, at least Izzy never truly addressed his trauma, they didn't have the talk or anything, they should go that tragic path full force. Edizzy dynamic until now was incredible, complicated, fucked up, codependent and if they had to kill him without letting him to fully grow, they should fuckin commit to this. It was too short, too sudden and too short again. We didn't get a heroic death nor a fully tragic one. Yeah, Izzy's speach was skickeningly sad (when it made sense, it not always did) but like, compare this to their scenes in s2e1&2. It just looks like nothing, it looks pathetic

#I know how distressing reading all those analysis is so I wanted to warn you beforehand#Not a nice feeling when you're in the middle of a long post just to realize the op is actually praising the finale#E8#Edizzy#I love e1&2#They show their fucked up relationship so much better#There's so much going on#About both of them#The words the subtext the metaphors the hidden emotions in their eyes#The time needed to do all that#Ending of e2 was perfect#That here was just short speech#It's like they didn't have the time to show so they just spelled it out#It felt like a speedrun#Ofmd s2#izzy hands

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

“You’re well-read, Ezra,” Mirabel remarks, sliding down from her perch.

“I’m well-mythed,” Zachary corrects. “When I was a kid I thought Hecate and Isis and all the orishas were friends of my mom’s, like, actual people. I suppose in a way they were. Still are. Whatever.”

-The Starless Sea, Erin Morgenstern, Book III: The Ballad of Simon and Eleanor, 4th Zachary section

I think this quote is the single most important piece of characterisation for Zachary Ezra Rawlins in the whole of The Starless Sea. Or at least it is for me (though I appreciate that there is a distinction between what you might value as a reader-for-pleasure and a reader-with-hellbent-ulterior-intentions-to-write-this-man-into-a-corner-watch-me-gooo). I kept coming back to this line as I wrote Fateheart (my fan-sequel to The Starless Sea - you can read it here on Ao3), and it has become the lynchpin for a lot of my thoughts about who Zachary is - especially as the story of Fateheart unfolded in front of me and I was trying to keep up with what was happening and grapple with why it felt inevitable.

Here are some of those thoughts, for any of you who are interested in thinking this much about Zachary Ezra Rawlins (and his relationship with Dorian, which is ever central to who he is), about myth, and about The Starless Sea by Erin Morgenstern.

One of the reasons I ended up writing my fan-sequel to The Starless Sea was a desire to continue following the story of what had already begun in Morgenstern's book, which is Zachary's descent into myth - and I don't mean his passage through the wonderlands beneath the world - I mean becoming one himself.

This quote captures what I love most about Zachary and what I find most powerful about him, which is something I came to think of whilst writing as his "belief in the real and the unreal". He is deeply post-modern, and has an acute grasp of myth (gonna define 'myth' in a truncated but convenient way here as a type of story which offers a moral or identity truth, alternative to a history, which gives you facts and assumes the 'truth' is implicit through them). The combination of these two things is very potent, and has allowed Zachary's sense of what is true to develop separately from and at times directly in opposition to what is factual or historically, empirically verifiable. Simply put, when it comes to making sense of his reality, historical truth does not interest him. Stories interest him ("He believes in books, he knows that much" - Book I: Sweet Sorrows, 3rd Zachary section). Not only does a rationalist presentation of value or truth not have any of the significance that it would in a modernist worldview, it is almost irrelevant to Zachary. He does not navigate the world according to its empirical qualities but according to its stories, and he is very adept at reading them, because these are the paradigms by which he got to know the world in the first place.

The blurring of reality into unreality which happens in the quote - he thought that the goddesses were friends of his mother's - "actual people" - tells us possibly more about Zachary's mother than about him. Or perhaps tells us so much about him by telling us about her first: Madame Love Rawlins raised her son in an environment which valued stories, and specifically myths, above all else. Zachary does not gain his sense of identity or context of self whilst growing up from integration into a historical narrative or a sociological connection to his own time or place - even his sense of a wider family context and adult society was defined by a profound connection to a global pantheon of myths. You can imagine how Madame Love Rawlins must have spoken about Hecate and Isis and the orishas - how effortlessly, personally, and often - to create an environment where they seemed this real. And you can conjecture that she herself was not in the business of drawing a distinction between her regular old human friends and the more divine voices of influence over her life. So why should Zachary?

But that blurring of reality with unreality is not nearly as telling as the other blur that happens in the quote above, which is, "I suppose in a way they were. Still are. Whatever."

This is three things happening in quick succession, and I think they are all equally fascinating, and they all delight me equally.

The last and least of them is in the word "whatever": it implies that Zachary is not interested in firmly deciding whether or not he thinks they are 'real' people. "Whatever" is applying to the question of past or present tense, but in its dismissiveness it waives any of the gravity of his placing his blurring of reality in the past. Yes, he's identifying that perception as a younger, past version of himself, but then he brings it forwards, catching himself: "I suppose in a way they were" reasserts the belief; "Still are" updates it, identifies it in himself now; "Whatever" carries it beyond what he feels the need to define.

The second thing that's happening is the "Still are." There is some ambiguity, but not much, in the quote - is Zachary supposing that these mythical figures may actually have been real? That's how I'm primarily reading it because that's the most obvious reading. But one could argue that he's equally supposing that they may well have truly been his mother's friends, and possibly still are - that he's not questioning their actuality so much as the familiarity of their role in one's personal world. They still are friends of his mom's. Or they still are real in some way. Either one is compounded by the "whatever", and "Still are. Whatever" is a telling rhythm of Zachary's thought process here: he is comfortable with indistinction. The factuality is not relevant.

But the most important and the first thing in "I suppose in a way they were. Still are. Whatever." is the supposing itself. That these myths are people who have had an impact on his life relationally, emotionally, interpersonally, and truly. Voices he has known and names he has called and referenced in conversation on the same level as any other. His almost throwaway acknowledgement that this blurring of the line between real and unreal is very much still part of his internal system says a great deal about how deeply foundational this sense of myth and truth is to him: the indistinction is not a problem with the thing, but the thing itself.

And never, in all his academic travels and independent adult life away from his mother (his independence of identity and situation is well established) has Zachary found reason enough to redraw the lines - to reassess this post-modern prioritisation of myth over history - to anchor himself according to what is real, regardless of the value of its truth, as opposed to what is unreal but true. And his wider characterisation as an academic at a good school and a devotee of stories in all forms tells us it is not for lack of self-awareness or intelligence. Assuming he has interrogated his own beliefs before, he clearly has not seen reason to dismantle his worldview. In fact, we possibly see the first thing in his life which really does force him to consolidate his beliefs, and it is not the real challenging the unreal, as must have happened to him and has not left a mark, but the unreal suddenly encroaching upon the real. The moment he assesses this internal balance of the real and the unreal is in the same chapter I quoted above (Book I: Sweet Sorrows, 3rd Zachary section), as he reflects upon seeing his childhood encounter with his door written in Sweet Sorrows and thinks upon what the book is telling him about what lay beyond it:

"He wonders why he believes it because someone wrote it down in a book. Why he believes anything at all and where to draw mental lines, where to stop suspending his disbelief."

Zachary is aware that he primarily operates in a territory where all disbelief is permanently suspended: this is not him asking whether he should start believing that this door did in fact lead to a Harbour - this is him wondering if he ought to believe this much that it does - and what it means for anything real if he carries that belief forwards as he intends to. Questioning whether the space he holds within him for the powerful truth of myth is now starting to truly consume the concrete, factual world in a way which is leading him into new territory. And it is. The mythical does in fact start to consume the real world for him. That is what happens to him in the rest of The Starless Sea. And this is the moment we see that crossover: he chooses to remain faithful to the unreal, and to pursue a story. He asserts what he was raised believing, which is that the unreal is more true and more valuable than the real, and therefore ultimately must be more real. Only someone who is intimately familiar already - from their earliest childhood - with the blurring of these lines - would react the way Zachary has to finding himself in a book - running with it, and allowing it to envelop him completely, as he is ultimately enveloped by the door, the Harbour, and the Starless Sea itself.

And what I love most about this passage is that we see it happen - we see him interrogate himself, we see him follow his internal logic, and we see his belief in the unreal win:

"Does he believe that the boy in the book is him? Well, yes. Does he believe painted doors on walls can open as though they were real and lead to other places entirely? He sighs and sinks below the surface."

To be fair he is in the bath in this scene, but also: "he sinks below the surface": he submits to the authority of myth over fact. And - crucially - to him, myths are real not as accounts of an abject moral value or a history, which is still quite abstract - what's real to him is myths as people.

Writing Fateheart was an exercise in loyalty to characters I fully believed in deeply, and for different reasons. I could write this much again about Madame Love Rawlins (and might/probably will) and Kat (might/probably won't) and don't get me started on Dorian (will/definitely will), but Zachary led the way for me here. I was fascinated - absolutely, devotedly transfixed by the process we get to see the start of in The Starless Sea, which is Zachary becoming part of a myth. He is the close of one story and then the beginning of the next, stepping from the periphery of one myth to the heart of the next.

So that became the paradigm for Fateheart: how do I take these characters, all of whom start as human, and draw from them a new myth? A story which is at once human and deeply personal and realistic in the sense of being true to human experiences of feeling and danger and cost and wonder and love, but is also more than itself - is broad and vast and contains profound, elemental gestures towards values and archetypes and fundamentals of what we are and choose and love as people?

And Zachary made it so easy. Because the myths are already people to him - real, breathing, blooded people. So his passage into that role was intuitive.

I find it wonderful that in the title quote here Zachary is correcting "well-read" to "well-mythed" - the difference is not one I was immediately tuned into, but one which turned out to be vital. He is able to navigate stories so cogently not because he knows them as books, but because he knows them as people. There is a reason he understands Mirabel the way he does - and loves her. He is used to relating to mythical, archetypal powers as close personal friends: he's been doing it since he was a child. Maybe meeting Mirabel forces that mental pathway out into the open - and cements it for him - but it was already there.

It is also the reason he is able to love Dorian the way he does - deeply, intuitively, and uncompromisingly. This relationship was a joy to explore for a number of reasons (most of which are bleedingly obvious hello i am a fanfic writer) but the most captivating dynamic (for me) is their respective positions with stories. Dorian tells them, carries them, gives them - Zachary receives them, loves them, and keeps them.

There's a language that developed organically for this as I was writing Fateheart, and actually grew from Morgenstern's own imagery: the deep night sky within Zachary - which in terms of vernacular I extrapolated from the details of Allegra's painting ("Zachary’s chest is cracked open, his heart exposed, the star-filled sky visible behind it"), developing into a way of referring to that space of pure and certain belief in the unreal - a vast constellation of myths, points of truth which connect across empty space to make sense of the world - which is Zachary's internal landscape.

When Dorian sits in the Gryphon bar and watches Zachary he cannot read him - though it is made clear that he can read just about everyone and everything else, and has been able to do so most of his life. What, then, is Dorian seeing? Most people are reducible to stories, but myths do not reduce to stories - they reduce to truths. Stories, at their best, might extrapolate to myths, which in turn reveal true things, but people are not usually myths - or if they are, they are myths first, masquerading as people (there are plenty of those in The Starless Sea.) And in Fateheart, I try to push this the other way by having three people slowly begin to masquerade as myths. And Dorian sees it first - long before there is language for it - or need for language for it, because, admittedly, there isn't need until you get deeper into the narrative of Fateheart. But Zachary is not a series of facts that build a narrative: he is a constellation of personal relationships with myths. He is a system of beliefs which merrily crosses the boundaries between the real and the unreal in a superb tangle of truths.

Dorian cannot read him because he is not a story. Nor is he, at that point, a myth - but he is a man whose grasp of the world hovers over the edges of what is real, prepared when push comes to shove to fall straight down the rabbit hole. Dorian cannot reduce him because he is already more than himself, hovering in the doorway of the unreal, beginning to follow his age-old belief into territory Dorian has been living in for a long time: the borderlands. Walking the face of the real world but allegiant to the unreal one.

How must Zachary have looked to him? An academic, operating within the structures and annals, the very factual, papery, process-laden architecture of the strictly real - yet relating to it as if it is one myth amongst many. Post-modernity in action: the historical, the rational, the empirical is just one more story. No more or less real than all the others he met at his mother's knee.

And how must Dorian have looked to Zachary? A man who clothes himself entirely in stories - who weaves between the language and the embroidered details of fables and legends and books - moving too quickly to be framed as either fact or fiction. Comfortable presenting the truth in a myriad of ways - with any name he chooses, in any shape he wills.

Dorian presents himself as a story - not just to Zachary, but to the world. Because it is an extraordinary position of power and an acutely slick one: in a world where most people think stories are not real and value them accordingly lowly, being a story allows him to control how he is perceived. From his name to every farthest extrapolation of his position and occupation he presents as fictional. Which is a very guarded way to walk the world. But Zachary draws absolutely no distinction between the people in his life who are stories and the stories in his life who are people. So Zachary is able to simultaneously accept that Dorian is a story and that he is a real person - able to hold the real alongside the unreal, and able to love it entirely as a self-contradictory package deal. Which must have been deeply disarming for a man who has mostly found that his ability to tell a story makes for a good way to present a false identity. Dorian is very good at being a story, but stories at their best extrapolate to myths, and Zachary knows how to love myths as people. He's been doing it all his life.

And this is where I watched them go in Fateheart. Zachary is more equipped to understand Dorian than Dorian is. He readily opens to him the space he holds within himself for stories - the well-populated night sky of the mythical, the unreal, the wondrous, the true. Zachary is a very, very good reader - which I am asserting by my own metrics, but I'll define it as this: if you can hold in perfect conjunction that a story is not true yet contains truth and is therefore more true, then you are a good reader. You can get more out of a truth if it's told in a good story than you can if it's presented as clean fact: a clean, dry bone of a fundamental is very clear and easy to handle, but you can see best how it moves when it is part of the dancing flesh of a living body - even though on one level you cannot see the bone anymore at all.

Zachary sees all the dressing and falls in love with the truth of who Dorian is - not in spite of the stories he hides within but because of them. He offers Dorian a way to make sense of himself - a way to make sense of his entire life, which has seen him caught over that boundary between the real and the unreal - serving a Harbour he never sees, hunting those who cannot be killed. Hiding in plain sight, operating beyond the limits of the real world without ever being free to cross into the unreal. And that grey area is very familiar to Zachary - he is unbothered by it and comfortable there.

And in return Dorian is the consolidation of Zachary's belief in the real and the unreal: he is at once a person and a story of himself. He is blisteringly close to being only the stories he tells and is told, and existing primarily as a way of delivering and performing those stories - and Zachary perceives him as an entire constellation: taking the stories he has become and focusing upon the truth in them. Seeing the bones in him even as they dance. Loving him as myth and human at once without drawing a distinction - and without needing to.

Writing Fateheart was an opportunity (or really a shameless excuse) to explore Zachary and Dorian's relationship with each other. They are just on the cusp of their lives colliding at the end of The Starless Sea, and there is enough substance there, enough tantalisingly unconsummated (ahem) chemistry, that it is a legitimately fun exercise to carry it forwards and see what happens. And I was delighted over and over again in writing them to discover the myriad ways in which they work together - ways they understand each other and overlap and seem stronger for it than they did on their own - all of which is full credit to their original characterisation. I had a distinct impression of following events that had already been set in motion - and rather than developing what an active, steady relationship looks like from scratch, revealing the outworking of what it promised to be from the off.

The blurring of these boundaries between the real and the unreal is literalised in their passage through the caverns of the Starless Sea: the two of them cross into fairytales, into stories and the settings of fables Dorian has told and memorised and had tattooed into his skin. But I do not think that their respective motions are in mirror image - for all Dorian is already living in the unreal, I think it is Zachary who carries the two of them into the territory of myth. In The Starless Sea they each traverse a wilderness of literary and mythical realities in an effort to find each other, but it is Zachary's trajectory that shapes the language surrounding him and his increasingly mythical identity in the book:

"And so the son of the fortune-teller does not find his way to the Starless Sea.

Not yet."

- Book I: Sweet Sorrows, chapter three - To Deceive the Eye

Zachary's process of heading down the path of fully embracing the unreal is his journey to the Starless Sea. The story hits its climax - and the old Harbour finds its breaking - when he finds it - but his actual passage into it is through the death of his physical, actual self.

Which, of course, comes at Dorian's hand. But the action of killing Zachary is two-fold: he frees him from the last traces of whatever he was clinging to of real, rational, folllowing-the-rules-of-a-normal-world life by pushing him entirely out of the world and into the place where the bees dwell - where the old gods are larger than life - where real, rational, following-the-rules-of-a-normal-world business is a vague, dollhouse style, boxy, undetailed approximation - a secondary feature, one worldview amongst a bigger context - and where he eventually drowns in the essence of the story itself, despite his final efforts to escape this. And then the completion of the process is to bring him back to the world - to take his body and replace the heart of what he is with something that is itself a story - a myth.

Dorian and Zachary are falling increasingly in sync with each other throughout The Starless Sea, but it is Zachary who leads the two of them to the shore of the thing itself - the very edge. Dorian is looking for a way to get home, which turns out to be Zachary, and Zachary is looking for a way to the Starless Sea, which turns out to be Dorian.

Dorian giving Zachary the heart - which is the heart of a story - 'of' in the sense of its position at the centre, but also in the sense of 'a heart produced by, having its origins in a story' - is the resolution of Zachary's passage into myth. He has travelled all the way to the Starless Sea - he has submitted to the dismantling of any last vestiges of scepticism in the face of the magic or absurd to such an extent that he has died for it - and then he is brought back.

And for what? To drift on a ship in the belly of the world, out of time, out of the story? Or is the absolution of his identity in that death and resurrection enough that wherever he goes he will bring with him the central, burning core of belief that makes stories like these possible?

At the beginning of The Starless Sea Zachary is in the process of returning to his old favourite books:

He has been reading (or rereading) a great many children’s books as well, because the stories seem more story-like, though he is mildly concerned this might be a symptom of an impending quarter-life crisis.

- Book I: Sweet Sorrows, chapter 4, first Zachary section

The eclipse of the mythical over the real, the reconnection with the powerful, foundational truth that what is fictional is just as real as what is physical, is already hinted at here: his instinct to draw closer to what seems like a purer form of story - worlds where the lines are blurred more perfectly, where the distinctions are already eliminated. This is the first sign of his overall character arc in this book - and it ends with he himself becoming a story.

And I love that he's concerned this might be a symptom of an impending quarter-life crisis. And I love even more that he's only "mildly" concerned. Because that's so Zachary: an intuitive sense that something's coming, and possibly something huge - and his response is to turn back to stories. The "mildly" here has the same feeling as, "I suppose in a way they were. Still are. Whatever." He is easy with a sense of deep upheaval. Because you can't shock someone with the unreal when they've known it all their lives.

He didn't open the door because he wanted to keep on believing that there was something behind it. He has resisted re-wiring his sense of how real all the orishas are not because he wants to keep on believing and knows he won't if he looks too hard, but because he absolutely believes it but is fearful of what this will mean for his grasp on the rest of reality and his place in it. Because really embracing this postmodernity means accepting that everything ultimately reduces to myth. That to walk truly in the deep places of what it means to be alive does not mean banishing a sense of madness but embracing it - following through to the point of total undoing - death of the real self - and further than that, into a new kind of life.

To sail the Starless Sea is to become the story of oneself. The air is haunted by the death and reformation of what is real. Only the bones of the real things ever return - dancing as part of the flesh they have been clothed in. Truth that is clothed in stories: myth.

Zachary Ezra Rawlins has known since he was a child that stories are true. And maybe his hesitancy to embrace this has been because he knows that if he embarks on this hero's journey he will have to leave behind anything that might resemble his own sanity by the world's standards. He knows that to embrace those relationships with the mythical as closely and as truly as he did when he was a child learning to relate to his mother's circle of friends will be to become himself a story. To relinquish his grip on the rational and to give up, ultimately, his heart.

To go mad, and to return more deeply yourself than you could ever have anticipated.

And you know who gets this? Dorian.

“How are you feeling?” Zachary asks.

“Like I’m losing my mind, but in a slow, achingly beautiful sort of way.”

“Yeah, I get that. So better, then.”

- Book IV, Written in the Stars, 3rd Zachary chapter

That's the second most important line for Zachary's characterisation - in my opinion (and let's face it when it comes to Zachary Ezra Rawlins I have an absolutely absurd amount of opinion). That once he chooses to cross the threshold of the world and walk the halls of a myth he's always suspected he had a part in, he knows that by some standards he is losing his mind - the rational part of his 'self' - his life, by the standards of what the world thinks a life is.

But he's only mildly worried about it. He's never really held much with the sense that rabbit holes ought not to be for falling into. That he should be beyond it. That it shouldn't be real.

The point of departure for Fateheart was a Zachary who has finally, with the aid of Dorian, become himself. A Zachary who has left behind the world and the life that went with it. A Zachary who is so at one with the mythical that he himself is a myth. Zachary at the final, gasping, awakening stage of losing his mind - but in a slow, achingly beautiful sort of way.

"So better, then."

A myth. A story told by someone who loves him well enough to bring him back as exactly what he always was: a heart alive and alight with the unreal, carrying it in the vast night sky within him, bright enough to illuminate the world and reveal all the things in it that have always been true:

[an] enormous, spinning truth, turning like a star in the sky, close enough to be a sun, burning with enough light to illuminate the world.

- Fateheart, part two, chapter 16

And Dorian follows him there - is the agent of the final stages of this transformation. Is the hand by which the story is told: one who tells the story, one who carries it.

It felt like the most obvious thing in the world that on the strength of such a pairing one could dream a whole new story - felt, to me, like it was clear that having transcended into myth, the new Harbour could and would form around them - could have at its centre a love story that is at once about real people and about something mythical.

The old myths are completed, and the new myths find their footing at the end of the story. And I wanted to know - was absolutely desperate to see - what the next story would look like, with these two people at the heart of it.

So that's what I wrote.

--BoogleBoot

#Zachary Ezra Rawlins#The Starless Sea#Erin Morgenstern#Fateheart#literature#books#Dorian#character study#I could write for this long again about Madame Love Rawlins alone#and don't get me started on Dorian#actually do#someone I beg you#I have so many thoughts about that man#about both of them

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

mrs dalloway, virginia woolf / crow, mount eerie

#these are the laat words in their respective works and this morning when i was really hungry on a coach i got incredibly emotional#about both of them#raph.txt#virginia woolf#mount eerie#phil elverum#mrs dalloway

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

we're having sex and you pull out at the end to discover your cock is entirely gone, dissolved (ive digested it like a pitcher plant). bye!

116K notes

·

View notes

Text

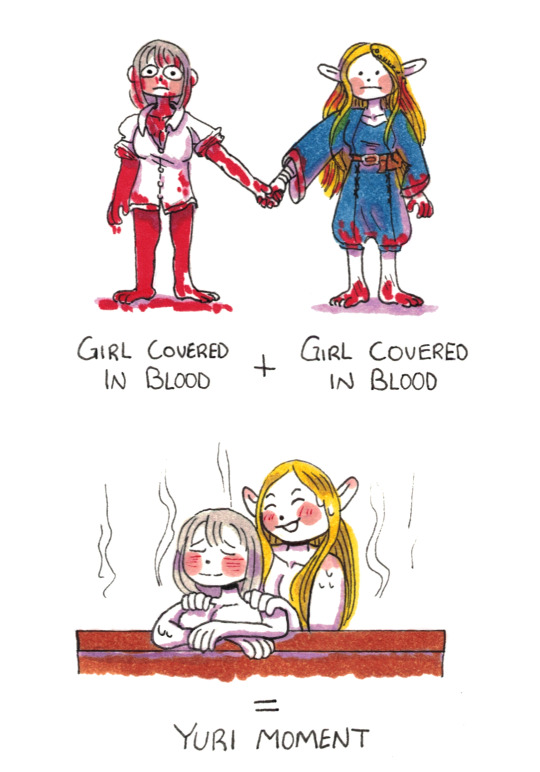

The math just adds up!

#dungeon meshi#falin touden#marcille donato#farcille#I always loved how chapter 27 ends with them both so bloody and 28 starts with them in the bath.#not just because of how iconic the bathtub moment is but because you know they had to scrap off so much gore first.#I think everyone in the party took a very long and methodical bath but Falin was basically *all* blood*.#Being covered in blood is one of those 'just girly things' that women deserve to stop being shamed about.#I just don't think Chilchuck is progressive enough. He probably made them take a bath first B*/#Okay jestering aside I want to just highlight -#The magnitude of Marcille's joy at seeing her dearest friend again! Of holding her and sharing her presence in the same room!#Something about this reunion feels like a beautiful dream you are afraid of waking up from...

35K notes

·

View notes

Text

A report just came out from a Palestinian hostage saying he was strapped with bombs and sent into a Hamas tunnel, with Israel prepared to blow the tunnel up with his body if fighters were found inside and yet people are still making the “Hamas uses human shields” arguments that have been confirmed to be a myth with no supporting evidence

#the hostage also said the same thing happened to a 15 year old boy hostage#both of them did survive as they were pulled out of the tunnel when no fighters were found and then released a few days later#the amount of people (including the US president) who still talk about the Hamas human shields is alarming#since no one has evidence of it and we have more then one piece of evidence of Israel using human shields#palestine#🦢

26K notes

·

View notes

Text

catalysts, protectors

#man those episodes#so many things put into perspective#like Simon’s role as a protector and his kindness and empathy and compassion and existence being the catalyst for the rest of ooo to#flourish#and Betty is a protector of Simon#I wonder if the last two episodes will explore more of her character? there’s so much to be explored about her giving so much of herself#to Simon but not thinking about what she wants for herself#do we get to explore her feelings or see her at all? will she have changed or learned to let go#I think there will be some sort of closure for the both of them#but at what cost#I am still crying over that scene with Simon’s memory of Betty and their song#my art#fionna and cake#fionna and cake spoilers#simon petrikov#betty grof#petrigrof#golbetty

28K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Greatest Showcat! [Lucihusk/Royalflush]

#hazbin hotel#husk#hazbin art#lucifer morningstar#lucihusk#royalflush#they're both performers! they both beef with alastor! they're both deadbeat dad coded.#something about lucifer's energy feels like it could be healing for husk idk i just want them to have a duet

11K notes

·

View notes

Text

Yeah, sure I’ll keep drawing Gerry and I’ll be so normal about it

#momoart#fanart#digital art#jonathan sims#the magnus archives#gerard keay#tma season three#I’m so normal about both of them

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

Average gotham knights experience (the game crashes not even 30 seconds later). Shoutout to @magnusj the most stealthy redhood player.

[Robin: OK. Let's do this SNEAKY STYLE.

[Robin: Jason NO-]

#gotham knights#tim drake#jason todd#robin#redhood#batfam#batman#dc#the fridge#dc comics#do people... still talk about gotham knights#cus they shouldnt#magnus n i playing and just both getting stuck on air seperately#watching them float a foot above the floor#love it

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

they should go on a fishing trip pt.1

#DONT COMMENT ON THE BACKGROUND I KNOWWWWWWWWWWWW#anyway this is day 1. they take a bus. the bakugo household has fishing gear so ´deku is wearing bakugo's onesoe (?) and bakugo is wearing#his dad's. and notices he has grown :')#anyway they take a BUS and don't feel like doing this at all it's awkward for so many reason#also trying to relax after everything is neurologically just really hard they might be hyperivgilant dik#and there's so much they never got to unpack bnut they have to and they have to start somewhere and with someone#deku makes that flower crown while bakugo preps everything and they both look at it and are thrown back into their childhood 🧍♀️🧍♀️🧍♀️#and at first they just sit and wait for the bavarian fish to bite (rody should make a cameo tbh) but then bakugo breaks the iceeee.#and he starts with their moms because their moms have been such a stubbron connection between these two :')#and deku answers with the usual 'good :) how's your mom :)?' and to everyone's surprise he actually opens up#and tells deku about his mom's insomnia because she watched her son die (that shit was live streamed tpo 10 bnha tweets btw)#idk i love to think of their moms being a very easy subject to connect through i think it's easier for them that way to be more vulnerablei#and then some fish biteeeeeeeeeeee#but like 3 small ones so they have to gather berries and mushrooms and make stew (dw there's an aldi this is bavaria after all)#but yeah day 1 is a bit weird like it's just them in the woods with no distractions#which is so different from whatever went on during their 1st year of high school#don't read this i will throw up i just need this somewhere this is my public scrapbook#bnha#deku#midoriya izuku#bakugo katsuki#the flower crown on their knees makes this a bit homosexual but fishing is always homosexual im not fighting against that#au:#fishing

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Vampire Misunderstanding

So! Danny got adopted by Bruce Wayne, but he doesn't know that Bruce is the Batman. He is just supernaturally oblivious to all things Batman related going on in the House.

But he does notice that Bruce leaves home a lot at night, that he doesn't like to go out in the day and often has his parties at night, and once or twice he's caught Bruce with a bit if blood still splattered on his cheek.

So he comes to the only plausible conclusion. Bruce is a Vampire.

He starts trying to hint at the fact that he knows, but doesn't want to just go out and say it. What if Bruce reacts negatively to him knowing? He's dealt with enough Supernatural Beings to know that they don't like other people (and especially other supernatural beings) intruding on their lives.

So Danny decided to subtly hint at it.

He started asking questions like "So hypothetically, how would you deal with having a Garlic Allergy in Gotham?" Or "So if you had very sensitive skin that could sunburn extremely easily, how much cloud cover would you need to go outside?" And "So what's your opinion on a High-Iron Diet?"

Basically just tossing out questions and trying to Guage Bruce's reaction.

He thinks he's doing a good job!

...

Bruce is certain that he has adopted a Vampire.

Danny is a good kid, but he has a few oddities that are hard to ignore.

For one, his skin is constantly Ice Cold, but he never seens to be bothered by it. As if he was an Undead that didn't require Body Heat anymore.

He also seems to like Hanging out in the Graveyard outside, and when asked about it he says that he is comforted by the place. Just like the Vampires he has met in the past, who feel comfortable when surrounded by Death.

And of course the biggest reason for suspicion is the fact that Danny seems to be hinting at it to him.

He keeps asking stuff like "How would you deal with a Garlic Allergy in Gotham?", probably trying to hint that he is a Vampire who can't eat Garlic, or asking about easy to sunburn skin, saying that he is probably not a Daywalker.

Bruce hopes Danny will just come clean about it soon, he doesn't want to intrude upon the kid when he is so obviously nervous about how he will react.

#Dpxdc#Dp x dc#Dcxdp#Dc x dp#Danny Phantom#Dc#Dcu#Danny thinks Bruce is a Vampire#Bruce thinks Danny is a Vampire#Misunderstandings#Danny is nervous about it because he has a bad experience with Vampires (vlad)#Bruce is nervous because he doesn't want to push Danny away#The Fenton Parents are still alive#They just lost custody of Danny after a CPS worker stumbled upon Amity and had an aneurysm#Jazz is off to college#Though idk if she went to Gotham U or some other College in a safer part of the country#Coincidentally neither Danny or Bruce actually like Garlic#And they both like to stay indoors#And both of them have caught the other with drops of blood on their faces and/or clothes#Idk where the other Batkids are#Maybe Danny was the first kid adopted by Bruce in this timeline?#Or the others are just coincidentally not in thr house at the moment

3K notes

·

View notes