#le mort darthur

Text

#king arthur#guinevere#lancelot#sir lancelot#arthurian literature#arthuriana#le mort darthur#the death of king arthur#medieval literature

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

i respect one (1) knight in le morte darthur and that knight is sir dinadan

#sir i would die for you#guy really took one look at a castle where to stay there you have to fight and beat two knights#and went no thanks i'd rather look for alternative accommodation#only to be dragged into it by tristram and then manage to gain entry#only to then be told that he has to fight with palomides and gaheris when they come to seek shelter#and turns around to tristram to say look i'm still knackered from fighting thirty knights a few hours ago and the two knights before#i've just been knocked off my horse by palomides#and quite honestly fuck this#(and then proceeds to say that lancelot and his eagerness to fight everyone landed him in bed with injuries for 3 months)#i love him your honour#he's just tired#anyway new blorbo acquired#sir dinadan#le morte d'arthur#le morte darthur#thomas malory#lit reads malory#arthuriana

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

Confessions of a medievalist: I have never read Mallory’s Morte Darthur cover to cover.

So I now present to you things I didn’t realize about Morte Darthur chapter 1:

Kay was still “nourishing” and was handed off to another woman so his mother could “nourish”baby Arthur. Meaning he was not old enough to get weened. So Kay and Arthur’s age difference is smaller then the three years (as I had always assumed) and probably no more then one.

Sir Ector (Kay’s dad, Arthur’s foster dad) knew the king was giving him this baby and got a lot of rewards for it. Yet when Arthur pulled the sword he was shocked and confesses Arthur’s blood was of a higher status then he’d assumed. This leads me to believe that he thought he was Igraine’s child by her first husband and the king was just getting rid of him like he did with all of Igraine’s daughters (marrying them of and then putting the youngest in a nunnery)

Morgan is sent to a nunnery and then married off. Which seems odd to me. But I guess Uther just didn’t want to raise her until she was ready to be married off.

Oh and Uther goes and gets himself into a war two years after arthur is born. It seems to be implying that’s why he never went to go get him. Which makes sense…but I still don’t like this guy, he killed a woman’s husband to sleep with her, raped her, didn’t tell her the baby was his and left her stressing about it for a good while, sent all her children away. If Merlin’s gonna manipulate him on his deathbed to secure Arthur’s throne I am not gonna shed a tear over it.

It didn’t say Arthur was 15. It’s left quite vague. All we know is he’s older then two. Which, I sure hope so

Kay knows what the sword is the second he sees it. It’s Arthur who doesn’t. Kay immediately goes “oh I guess I’m king now” and goes to tell his dad but is completely willing to explain that Arthur found it and seems not to care that Arthur gets the crown.

Arthur swore as long as he lived he’d never let anyone but Kay be steward. Like that’s an oath he takes. Explains a lot about the Dutch tradition and why he never gets fired.

The aristocracy kept trying to delay his coronation. It’s kinda funny.

#arthurian legend#king arthur#Morte Darthur#sir thomas malory#sir Kay#Kay#Sir Ector#king Uther#king Uther is the worst#morgan le fay#she gets mentioned!#Igraine deserves so much better

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

I am not going to lie, a highlight of malorydaily will be getting to read the scene where lancelot gets shot in the ass as a collective

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

i'm usually very suspicious of retellings, yet reading le morte darthur for class has got me thinking.... prettyhands...

#judith.txt#i hate the modern saturation of retellings and reboots#AND YET#sir beaumains/prettyhands tempts me#is this because of the morte darthur cds i used to listen to on long car journeys when i was little#not child appropriate#the collapse of camelot filled me with dread enough to make me cry#but i'm afraid the way they told that story stuck with me#and there are some interesting titbits in le morte

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

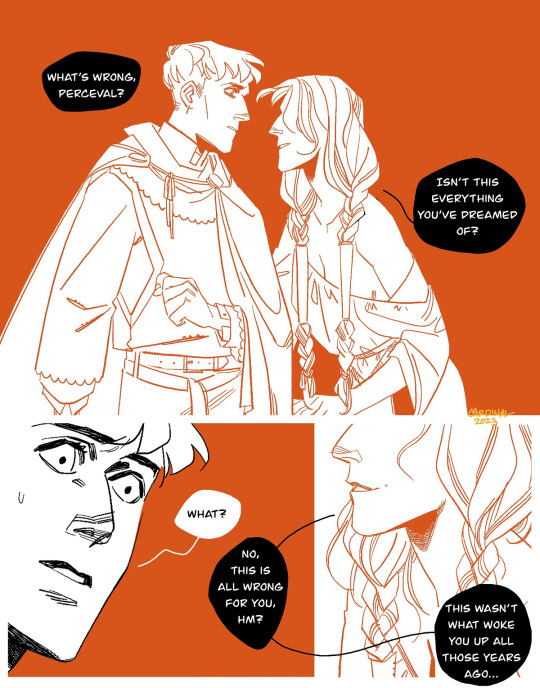

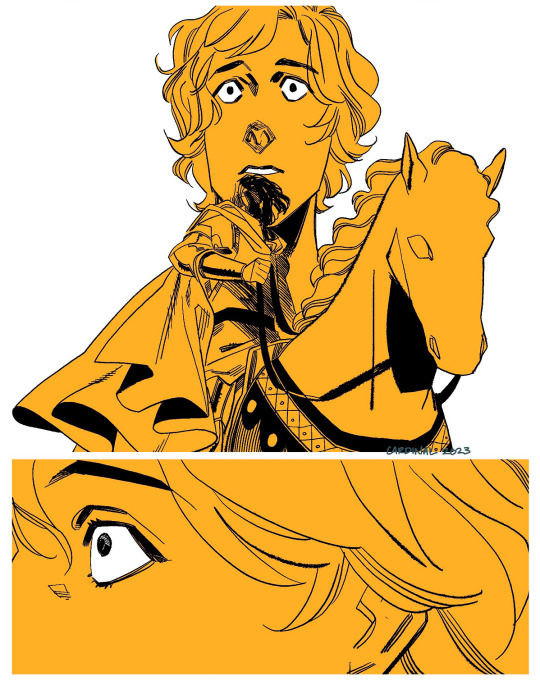

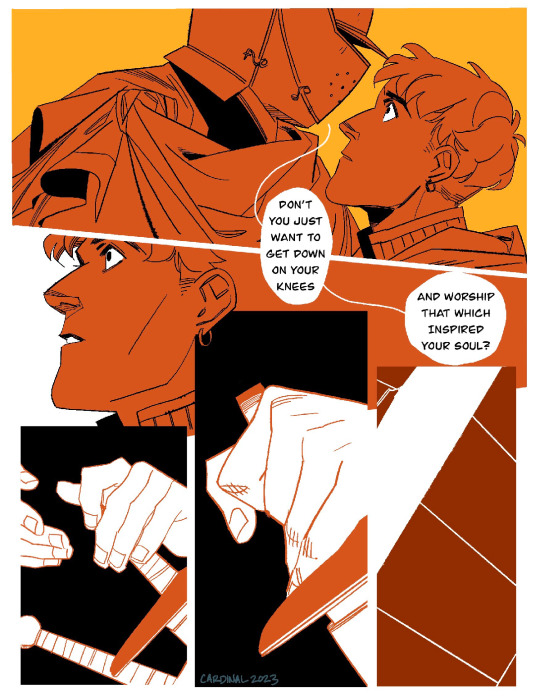

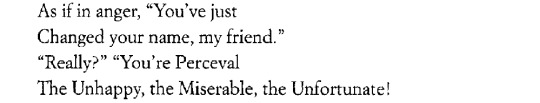

PERCEVAL THE UNHAPPY, THE MISERABLE, THE UNFORTUNATE, THE FISHER KING!

Perceval, de Troyes (trans. Burton Raffel)

ALRIGHT alright. so previously I did an illustration that explained the premise of all this, that it's inspired by the narrative choices that Bresson made in his film Lancelot du Lac etc

to dive in more into it (because this is something like derivative fiction. I'm putting concepts into a blender and seeing what comes out of it): the setting is haunted by the previously existing narratives that started cannibalizing each other until it regurgitates itself into the more well known narrative beats, and something else about the invasive rot of christianity and empire mythmaking into settings. it's an intertextual haunting, if you will! and this scene takes place during the grail quest narrative, but the temptation of Perceval plays out differently.

in both Chretien (and Wolfram's) Perceval narratives, what 'wakes' Perceval up (in more ways than one. desire and self actualization in one go!) is seeing knights, something his mother tried hard to keep him from. so instead of the temptation of lust & etc in the Morte narrative taking the form of a lady, it takes the form of a knight. the temptation to renounce one's faith to serve something else remains.

so Perceval still stabs himself, but instead of continuing on the grail quest in the shadow of Galahad, he becomes the narrative's Fisher King because his earlier state of being as a the grail quest hero is creeping back into his marrow. it was waiting for an opening, and stabbing yourself in the thigh is one hell of a parallel!!!

that wound isn't going to heal buddy, and the state of the setting will now be reflected on your body. sure hope that Arthur hasn't like. corrupted the justice of the land or anything. that sure would suck for your overall health.

all the red in this sequence is because in de Troyes' Perceval, Perceval takes the armor of the Red Knight and becomes known as the Knight in Red.

and now for the citations, which I will try to order in a way that makes sense!

Seeing Knights For The First Time

Perceval, de Troyes (trans. Burton Raffel)

The Temptation of Perceval

Le Morte Darthur, Mallory (modernized by Baines)

The Fisher King, and Perceval The Unfortunate

Perceval, de Troyes (trans. Burton Raffel)

On Perceval and Gender, etc.

Clothes Make The Man: Parzival Dressed and Undressed, Michael D. Amey

On Wounds

Wounded Masculinity: Injury and Gender in Sir Thomas Malory's Le Morte Darthur, Kenneth Hodges

The Red Knight

Perceval, de Troyes (trans. Burton Raffel)

On Arthur and the Corruption of Justice

The Failure of Justice, the Failure of Arthur, L.K. Bedwell

#long post#GOD IS IT A LONG POST#i am so so sorry for that.#knights knights knights!#komiks tag#blood cw#if it wasn't clear: i dislike galahad so much. he represents so much i cant stand and worst of all he ROBBED MY MAN#OF HIS NARRATIVE#but like. what's christianity but theft acting uwu innocent about all the shit they did tbqh#fucking. la croix jesus christ over here.#sir perceval

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

a fun thing abt me is that I will get drunk and I will start handing out my belongings

0 notes

Text

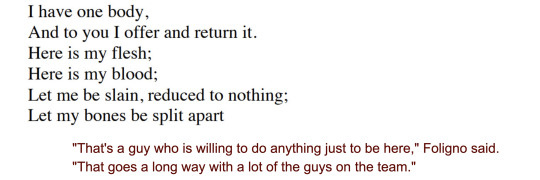

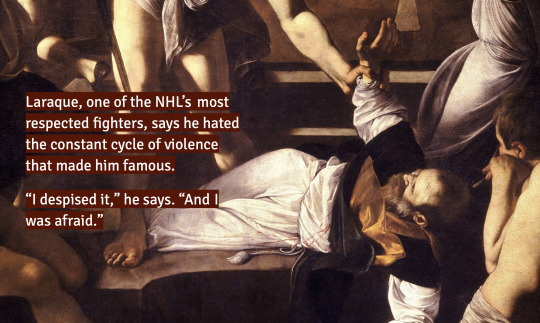

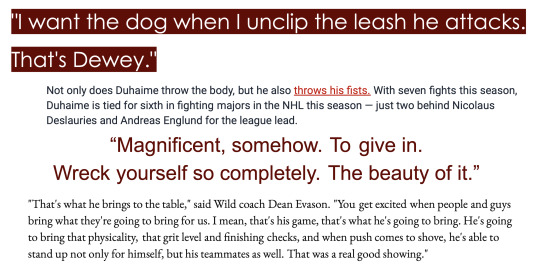

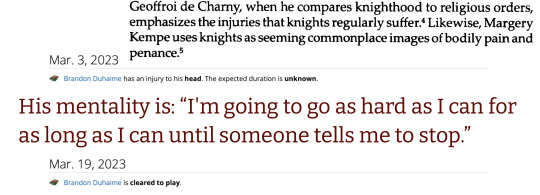

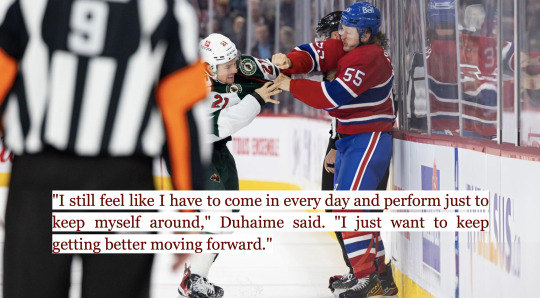

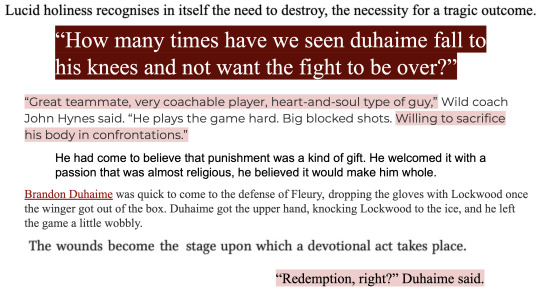

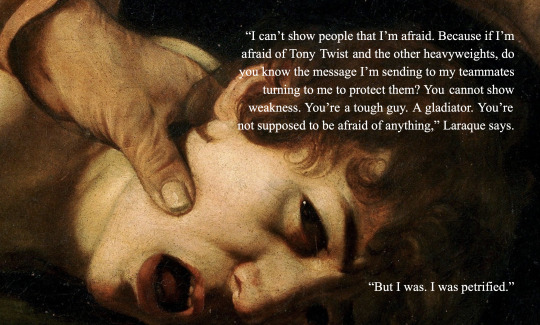

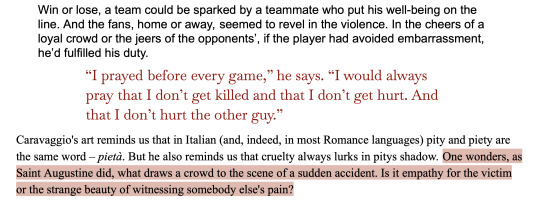

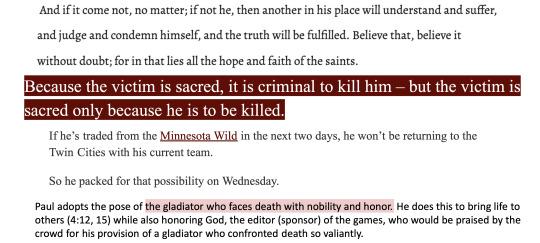

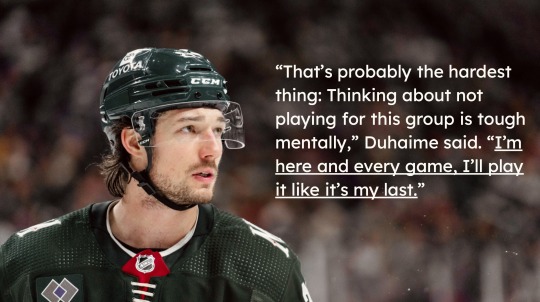

The Pugilist

Joe Nelson, Fan films unreal view of Vancouvers Kyle Burroughs hammering Wilds Brandon Duhaime | Ariel Glucklich, Sacred Pain: Hurting the Body for the Sake of the Soul | Canucks Army, Analyzing what the Canucks might like about Wild forward Brandon Duhaime | Mikki Tuohy, NHL Trade Rumours: Will the MN Wild Trade Brandon Duhaime? | René Girard, Violence and the Sacred | Kayla Hynnek, Brandon Duhaime Brings It Every Night For The Wild | Max Bultman and Dan Robson, The mental toll of hockey fighting goes beyond getting ‘punched in the face’ | Joel Auerbach via Getty Images | Anne Sexton | Kayla Hynnek | 1 Corinthians 4:9 | Bultman and Robson | Catherine of Siena, The Prayers of Catherine of Siena (trans. Noffke) | Tyson Cole, Analyzing what the Canucks might like about Wild forward Brandon Duhaime | Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, The Martyrdom of Saint Matthew (c. 1599-1600) | Bultman and Robson | Joe Smith, ‘Vintage Flower’: Behind the scenes of Marc-Andre Fleury’s emotional night in Wild’s win | George Bataille, Guilty (trans. Bruce Boone) | Toni Calasanti, Feminist Gerontology and Old Men | Becoming Wild: Brandon Duhaime via YouTube | Cole | Eimear McBride, The Lesser Bohemians | Cole | Vitor Munhoz, NHLI via Getty Images | Elly McCausland, 'Mervayle what hit mente': Interpreting Pained Bodies in Malory's "Morte D’Arthur" | Capfriendly: Brandon Duhaime Injury Updates | Calasanti | McCausland| Kenneth Hodges, Wounded Masculinity: Injury and Gender in Sir Thomas Malory’s Le Morte DArthur | Becoming Wild: Brandon Duhaime | Dieric Bouts, Christ Crowned With Thorns | David Berding via Getty Images | Bataille | Brandon Duhaime vs Will Borgen Feb 24, 2024 | Michael Russo and Joe Smith, Brandon Duhaime traded by the Wild: Why they moved him, and what he adds to the Avalanche | The Winter House (2022) dir. Keith Boynton | Joe Smith, Wild’s special teams deliver, Fleury exits early on ‘Fight Night’: Key takeaways vs. Panthers | Vibeke Olson, Penetrating the Void: Picturing the wound in Christ’s side as a performative space | Joe Smith, What Brandon Duhaime’s deal means for Wild salary-cap situation and Filip Gustavsson talks | Girard | Ocean Vuong, Devotion | Caravaggio, Sacrifice of Isaac (1598) | Bultman and Robson | Bultman and Robson | Bultman and Robson | Amelia Arenas, Sex, Violence and Faith: The Art of Caravaggio | Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Brothers Karamazov | Girard | Michael Russo and Joe Smith, Wild GM Bill Guerin working phones ahead of trade deadline, no regrets over training-camp extensions | Concannon, “Not for an Olive Wreath, but Our Lives”: Gladiators, Athletes, and Early Christian Bodies | Matt Blewett - USA Sports | Michael Russo and Joe Smith, Wild trade tiers: Who is on the block? Who could be dangled? Who is untouchable? | Thornton Wilder, Our Town

#this got slightly out of hand#but i stand by it#brandon duhaime#parallels#blasphemy#hockey poetry posts#sorta kinda#minnesota wild

180 notes

·

View notes

Text

blue books, blue candles, blue feathers, blue mood, blue background, blue sky

The Warden by Anthony Trollope

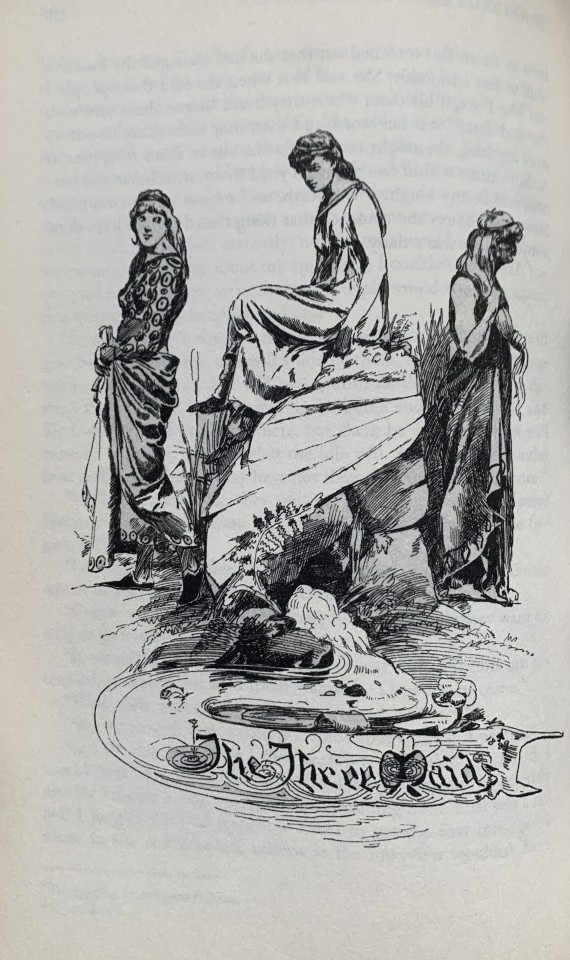

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court by Mark Twain (images taken from this book).

Wives and Daughters by Elizabeth Gaskell.

Le Morte Darthur by Sir Thomas Malory.

#books#dark academia#reading#light academia#literature#academia#lit#classic academia#bookblr#nejj bookblr#book blog#book recommendations#classic literature#english literature#booklr#photography#book photography#cozycore#softcore#fiction

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

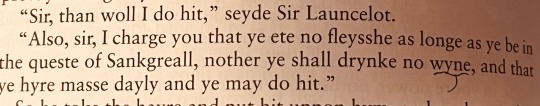

Text reads (modernized by me):

“Sir, then will I do it,” said Sir Lancelot.

“Also, sir, I charge you that you eat no flesh as long as you be in the quest of the Holy Grail, neither shall you drink wine, and that you hear mass daily and you may do it.”

Saw this passage in Le Morte Darthur, where a hermit is having Lancelot take some vows, and it struck me as odd. This is a holy man helping Lancelot on a holy quest for a holy relic and he’s just barred him from taking communion. No wine, no communion. And you’d think that engaging in church rituals would be encouraged on a quest of this nature, not banned.

“Ah,” you might say, “but transubstantiation*! The wine isn’t wine!”

Okay, sure. But if the wine is really blood, it follows that the bread is really flesh. And he can’t have that either, so he still can’t take communion. It gets you coming and going.

I want to see this guy’s hermitting license.

*a word which autocorrect believes is supposed to be “tea substance”

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

when you need a secret identity but creativity isn’t your forte:

[ID: a cropped picture of a page from Book 8 ('Sir Tristram de Lyonesse') of Thomas Malory's Le Morte Darthur. The highlighted line, spoken by Sir Tristram in disguise in Ireland, reads: 'my name is Tramtrist'. End ID.]

#HOWLING#this dumb bitch (affectionate)#please let it be that angwish and his queen are like 'huh tramtrist is a very similar name to tristam who murdered a close family member'#and tristam is just like yeah he's my evil twin we don't get on#don't worry though i'm not like him at all#if that happens i will LOSE MY SHIT#ah i'm having a blast#lit reads malory#arthuriana#sir tristram#sir tristan#thomas malory#le morte d'arthur

181 notes

·

View notes

Text

If one can set aside, for just a moment, the major objection that Christine de Pizan would have had to Isode’s and Guinevere’s adultery, it is worth observing how they both in fact possess many of the traits she believed made a good queen. Christine advises queens to gain support of powerful people, and both Isode and Guinevere appear to be politically adept, as they secure the support of allies: the barons defend Isode when she drinks from Morgan’s horn, and Guinevere reclaims support after the poisoned apple incident, re-establishing her allies in the roll call that signals her Maying expedition. Christine also promotes charity, and warns princesses not to overindulge in their wealth, one of the main ‘temptacions’ that can plague the rich; while the day-to-day accounting and practical affairs of a queen are rarely, if ever, recorded in romance, Isode demonstrates that she is no slave to wealth when she offers to live with Tristram in poverty, and Guinevere is willing to spend a small fortune on the recovery of Lancelot following his madness. Christine suggests that a sensible queen will ‘tendra discrete maniere meismement vers ceulx que elle saura bien qui ne l’aimeront pas, et qui aront envie sur elle’ [maintain a discreet bearing even towards those who do not like her very much, and who will be jealous of her]. While Christine warns against those who envy queens for their power rather than beauty, her advice might still work as a relevant backdrop for Malory’s two queens, who show no signs of jealousy at all despite being constantly compared to each other by their admirers. The solidarity of women in Le Morte Darthur is also extended between women of different social status: Isode has a good relationship with Brangwain, as well as Guinevere, again adhering to Christine’s advice for ladies, for she stresses the importance of having the favour ‘de tous les estaz de ses subgiez’ [of all the estates/classes of subjects], and, in particular, of ladies in waiting and female companions. While the French Iseut plots against her maid and contemplates killing her at one point, Malory omits this entire episode completely, strengthening my claim that his women may be positioned as much-needed models of civility and empathy for the envy-ridden knights.

— Women of Words in Le Morte Darthur: The Autonomy of Speech in Malory’s Female Characters by Siobhán M. Wyatt

#i might be misremembering but i'm pretty sure the attempt upon brangaine's life is still there?#only it's organized by other servants and not by isolde#anyway *jo march voice* women-#arthuriana#arthurian legends#isolde#guinevere#brangien#brangaine#what was my tag for her ugh#le morte d'arthur#gella talks arthuriana#talk talk talk

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

i need u all to read this bit in le Morte Darthur where Lancelot sleeps in an empty bed and the knight whose house it is “““mistakes lancelot for his wife’”” and tries to sleep with him. and then they fight about it. culminating in the knight ‘yielding himself to lancelot’ which is a normal medieval way of saying surrender but like…sure

#i read it out to my mum and she went ‘oh they had their swords in their hands did they? yeah i bet they did’#sorry i know no one fucking cares about middle english knights but i do!!!!!! also this is me revising for my medieval lit exam so#at least there’s a good reason for my extremely lame interests <3#h.txt#arthuriana

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

The fantasy in modern Arthuriana (3)

A follow-up of the previous post.

If the medieval Arthurian literature accumulates the tales of the feats of the heroes, the detail of their thoughts is mostly left in the shadows. Like the prose of Malory says for a good number of knights, “He said but little”, “He seyde but lytyll”. In other words, the Arthurian romance of the Middle-Ages is concerned with actions, not words. It is even truer when it comes to the female characters, a minority among the Arthurian adventures, and who are limited to a specific set of roles: queen and giver of goods (Guinevere), virgin and emissary of adventure (Linette), sad and dying lover (the lady of Escalot)… Such a restriction of functions invited in itself a fleshing out of the characters, not to say a remake. It is even stronger when we come to the sorceresses, another type of women largely used by modern rewrites, probably because they are precisely among the female characters the only one who, in the Middle-Ages, can freely participate to the action. [It is true that the maidens who guide the knights throughout their quests seem to also have an important area of action, but very often it is suggested that they belong to the supernatural world. In the Morte Darthur, the three ladies met by Gawain, Yvain and Marhalt embody the three ages of woman; Linette, who guides Gareth and helps him in his love, is able to “piece back together” and resurrect a dead knight].

If the revisited Arthurian literature likes to give a voice to women, these characters so often overshadowed by their male counterparts who are always in a war or on a quest, it is probably because at first it was an innovation. Since everything was already said in the past, one of the simplest ways to renew the tale is to give a voice to the mutes, here women. This innovation was very quickly assimilated to a feminist, though not always feminine, current, under the major influence of Marion Zimmer Bradley and her “Mists of Avalon”. In it the focus is placed on the enchantresses, Viviane and Morgan mainly. Given the huge success of these novels, the characters within it had a tendency to influence, consciously or not, ulterior treatments of the Arthurian fiction and its female characters. As such, when Cindy Mediavilla wrote about “The Mists of Avalon”, she said “[it] sets the standard for Arthurian fiction told from the female perspective. Heavy with images of the Goddess versus the male dominance of Christianity, this story (…) is highly recommended for all fans of the genre, especially young feminists seeking alternate renderings of the legend.” (Arthurian Fiction – An Annotated Bibliography). Outside of this “feminist” dimension, there is still a great number of recurring trends discernable within contemporary novels that have a direct influence over the idea of magic, and by extension, the genre or sub-genre to which the Arthurian novel belongs. [Maureen Fries heavily nuanced the feminism at work here: Viviane is killed by Balin, Nimue killed herself after betraying Kevin, Niniane is used then killed by Mordred, Morgan ens up admitting the universality of religious symbols even assimilated the Great Goddess to the Virgin Mary… “Indeed, real empowerment escape all of the women in the book except perhaps (and indirectly) Gwenhwyfar, whose narrow Christianity Arthur embraces.” – “Trends in the Modern Arthurian Novel”, in “King Arthur Through the Ages”]

The duo Viviane/Morgan is most often treated as an antagonism. In line with the sources, Viviane appears as a kind fairy who raises Lancelot and acts to help Arthur dispel the schemes of his malevolent half-sister. [With a rare set of exceptions, including Fred T. Saberhagen’s Dominion which subverts many preconceptions by making Viviane a bloodthirsty high-priestess and Merlin a drunkard with a failing magic, closer to the buffoon that appears in the BD “Le chant d’Excalibur” by Arleston and Hübsch than to the medieval prophet] But the shadows among the medieval characters are enough to allow anyone to interpret them in various ways. Indeed, this sweet Lady of the Lake is also the woman that used Merlin to augment her own power before imprisoning him for all of eternity. And Morgan is at the same time the enemy of the Round Table and the crying sister which takes a dying Arthur in her arms to carry him away to Avalon. This ambiguity is complexified by numerous possible divisions or assimilations: Viviane is also Niniane or Nimue, except when they are all different characters. Mordred is either the son of Morgan, or of her sister Morgause. The sources vary a lot about these facts, and so do the modern authors – and the same thing applies to the love-romances that are woven between the enchantresses and their victims, between Merlin and his students. [Within the “Lancelot-Graal”, Morgan is said to have been the student of Merlin, but she is different from Viviane, another of his student who ended up imprisoning the wizard. Yet, there is a temptation to synthetize in one character the student, the mistress and the enemy. On another subject, the hatred of Morgan for the Round Table could be explained by her love for the cousin of the queen, a love that said queen managed to destroy. As early as the Middle-Ages we see the beginning of, not a rehabilitation, but at least excusing circumstances for Morgan’s criminal behavior towards her brother and his kingdom.]

The opposition of benevolent sorceresses and malevolent wizardesses is inscribed in a broader way within a specific conception of magic. If we can easily admit that there are things such as “white” or “black” magic, if we admit that there are wizards opposing witches (or necromancers), than this duality invokes the symbolism of good versus evil. In the context of the Arthurian legend, the magic that serves Arthur and his chivalrous ideal is supposed to be white, while the one of those that stand against him is black. It is the case with Stephen Lawhead or Gillian Bradshaw, where the future of the world depends on a battle between Light and Darkness. [Gillian Bradshaw created “Hawk of May” and “Kingdom of Summer”. The expression “Kingdom of Summer” is also very present within Lawhead’s work, reinforcing the link between those two authors. Lawhead prefers to name two of his characters Gwalcmai and Gwalchavad, “hawk of May” and “hawk of Summer”, rather than Gawain and Galahad. As for the opposition of the Light and the Darkness, we can be reminded of the two sides of the Force within “Star Wars”, which is filled with Arthurian references.]

But this symbolism also evokes several moral values that already prepare the question of how magic and religion coexist. Already in the Middle-Ages the limits are blurry when it comes to separating magic, religion, and science – especially medical science. (See Richard Kieckheffer’s Magic in the Middle-Ages) The knowledge of plants can be seen with suspicions, and the various invocations look very similar to each other, no matter if they are for a saint or a demon. All those contradictions coexist within the modern Arthurian literature as a whole, even though if most authors take care to establish a cohesive magic system within the setting of their tale.

As such we frequently have an opposition between magic and religion, where magic relies on nature and traditional beliefs of which women are the bearers, while religion relies on a recent importation of Christianism and is presented as repressive and misogynistic. It is the case in Marion Zimmer Bradley’s work, where the magic is natural, “sympathetic”, against fanatical Christians who only dream of absolute power. Bernard Cornwell depicts a desacralized Christianity in an even darker light, as a religion only concerned with accumulating wealth by exploiting naïve pilgrims. The prayers are emphatic but useless, and the priest Samson, a future saint, has a rat-like face, a strong dislike of Guinevere and Nimue, as well as a heavily hinted preference for very young monks. The only Christian that is acceptable to the eyes of the narrator is the bishop Bedwin, who turns out to not be a quite faithful Christian, and an emblematic example of the improbable reconciliation of the extremes within modern Arthurians – a treatment of magic an religion that prefers the opposition of forces rather than their complementary. It forms indeed an explosive situation that is able to captivate more the attention of a reader rather than an idyllic statu quo. As such, what imposed itself as an Arthurian topos is the idea of a mostly pagan Britain attacked by the hegemonic projects of Christianism – despite the historical and archeological informations contraicting this view. The historicizing of the Arthurian setting is thus sometimes independent from the story, while not negating its realism or “vraisemblance”. [Adam Roberts, in “Silk and Potatoes” pointed out that in Lawhead’s work the Briton peasants are wearing silk, which is highly improbable, and that they cook with potatoes, an obvious anachronism.]

Stephen Lawhead tries to have a pacific shift from the old religion and its beliefs (assimilated to magic) to the Christian religion of the God of love. Taliesin, then Merlin, both have a revelation of the unicity of the divine, and as such their bardic invocations are now addressed to the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit, but they stay unchanged in language or effect. What was once a spell or a trick becomes a miracle. Lawhead’s tale however is flawed by an oversimplification. If all this “magic” comes from God, then where do Morgian’s wicked powers come from? The unbreakable faith of Merlin within the superiority of God over Satan is admirable in a catechism context, but it removes an essential tool of the tale: its suspense. A duel between Morgian and Merlin during which the latter won’t suffer any blow, protected as he is by the armor of his faith, is quite disappointing, not to say boring. And what about the magic of the Small Folks, which seems to need a technical learning? The tale cannot fully escape a certain number of expectations, such as the oppositions between white and black magic, or between paganism and Christianity, or the presence of another “fairy”-like people cohabiting discreetly with the Britons. As such, while the attempt at Christianizing the supernatural is interesting because quite rare today (though it was very common in the Middle-Ages), is works badly.

It is a testimony of the weight of obligatory elements within the modern Arthurian fiction, a fiction that was shaped as much by contemporary successes as by, if not more than, its relationship to the medieval sources. If the articulation between magic and religion can be done in various ways, it stays in many cases a strong opposition between white magic/women/tradition, and religion/men/change. And since, outside of Merlin, most of the wizards of the medieval romances are women, magic is thus colored by femaleness, not to say feminism. In a world where male characters kill each other with weapons, women heal wounds with herbs and words. The image of the healer-Viviane, sweet and motherly, is opposed to the brutality of a world of warriors. At another level, it seems that the sorceresses embody the “fantasy temptation” while the warriors embody the “historical temptation”. [Raymond H. Thompson notes the gendered polarity within Arthurian rewrites since WWII, between a feminine movement closer to heroic fantasy, and a male movement, bloodier and closer to sword and sorcery (“Arthurian Legend in Science-Fiction and Fantasy”, in “King Arthur Through the Ages”)] As such, the novels that focus on the female characters also focus on magic, while those concerned with men and their wars are historicizing the Arthurian era. As Thomson said: “The focus thus shifts from warfare to the political and domestic conflicts that raise Arthur to power, and then destroy him.”

But if this is the case, where do we place evil wizardesses such as Morgan? They find their place within the rewrites that use abundantly of the supernatural, which is then vast enough to include both good and evil. Moreso, if the Middle-Ages offered a complex depiction of the enchantresses, the dark side of Morgane/Morgause stays dominant. Modern rewrites thus very easily use this malevolent aspect. It is the case of T.H. White whose second book, “The Witch in the Wood” was later renamed “The Queen of Air and Darkness” to designate Morgause. Gillian Bradshaw also depicts a fully evil Morgause who tries to teach her son Gwalchmai the occult arts. But he prefers the side of Light, and he joins Arthur and his knights. We find these two influences within Lawhead’s Morgian, also qualified of “Queen of Air and Darkness”, and who serves the Devil while Merlin fights by the sides of Arthur, the champion of Light. This distribution of the magical forces intensifies the motif of the conflict on several levels. The Darkness can be historical: the one of the “Dark Ages” at the beginning of the Middle-Ages, the one of the various disasters (war, plague, famine, insecurity) brought by the Saxon invader. But in a cyclical point of view, which extends the mythical side of the Arthurian theme even in rewrites that try to be historical, the fight between Good and Evil becomes recurrent. Arthur and Morgan (or her avatars) are easily identifiable archetypes. This repetition ability highlights the non-temporality of the myth and justifies the growing number of Arthurian rewrites: the myth is eternal, and thus must be eternally retold.

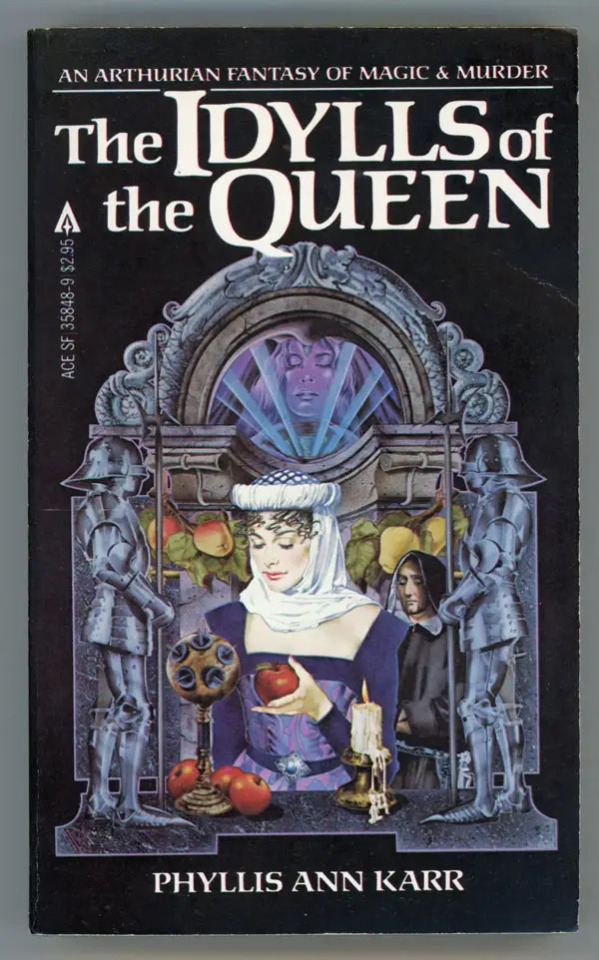

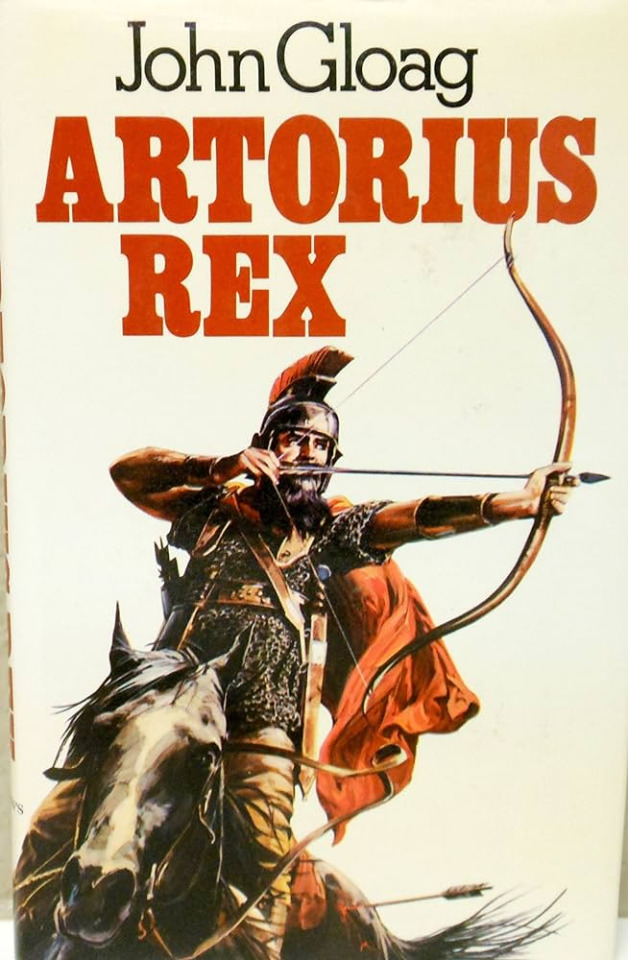

But these retellings do not simply replay the classical gigantic fight between the servants of the Light and those of the Darkness. A quite important number of modern authors chose to rehabilitate the unloved characters, mostly by giving them a voice. As such, the grudge-bearing, jealous witch of the medieval romances disappears, replaced by a loving and healing sister. Phyllis Ann Karr, within “The Idylls of the Queen”, offers a clever treatment of the character of Morgan, rehabilitated by a systematical refutation of the rumors, those that will become the “official” version of the legend later on. Morgan recognizes the facts, but offers other explanations for them, motivations misunderstood by her contemporaries and thus doomed to stay unknown (until the modern author reveals them, of course). This modern process of subverting the medieval stereotype (here the wicked witch that becomes the most faithful and loving servant of the Arthurian grandeur, pushing the devotion to a refusal to be offended by her bad reputation) can be declined in an infinite way, even on a parodic tone. Thomas Berger offers an anemic Galahad barely able to ride a horse, instead of the invulnerable knight supposed to be an “improved” version of his father Lancelot. John Gloag paints a Merlin prone to mistakes within his prophecies, and makes the entire announced and expected Arthurian glory a huge prank. T.H. White made his Lancelot ugly, where the Middle-Ages encouraged to see him as beautiful since he was “the perfect lover”.

However, as with all process, this technique has its limits. By constantly subverting the reader’s expectations, we create new demands. Morgan is constantly rehabilitated, Lancelot is constantly made darker or disgraced by modern authors, who are numerous (maybe too numerous?) in trying to set themselves apart from their predecessors. Cornwell’s Lancelot is an arrogant coward, while in other novels he simply disappears as the lover of the queen and/or the right arm of Arthur. He is replaced by characters deemed more historical (Bedwyr for Rosemary Sutcliff or Joan Wolff), or by characters invented for the plot (John Gloag’s Wencla, Victor Canning’s Borio). As if suppressing the greatest Arthurian knight was needed to surprise the modern reader. Under such a light, the rehabilitation of witches as misunderstood sorceresses is almost becoming more stereotypical than the original model of the “truly wicked”.

It seems that, for now, the only true novelty that modern authors have not dared is an Arthurian novel without Arthur. But this path seems to be under exploration: Arto, Artos, Artorius, all spellings that can establish a difference with the original character is welcome, especially if it establishes a gap between the foggy and uncertain time when the legend was born and the era of the modern rewrite. The exploitation of the Arthurian prehistory is another sign of it. The Arthurian novel without supernatural is also another facet of this quest for a renewal. But since the “pure” historical novel has already been done in the past, the “new novelty” is the reintroduction of the marvelous – not in its original form, but in a subtler one influenced by the past historicizing. We entered an era of “rationalizing” and “walling” of the “merveilleux”. Rationalizing the wonderful means exploiting events and actions that can be given the appearance of magic ; “walling” the marvelous means limiting magical abilities to a specific group of characters, usually non-humans and thus marginalized.

#fantasy#arthuriana#arthurian novels#arthurian literature#viviane#lady of the lake#morgane#morgan le fay#magic#magic system#fantasy novels#fantasy worldbuilding#magic vs religion#merlin#nimue#morgause#lancelot

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

loving each other won’t save us, but it won’t hurt either…

my two favourite underrated knights, sir urry and sir lavain. i was struck by how close they seem in the closing part of the morte, particularly how they stick by each other and lancelot as everything starts to unravel. thus, an imagined moment during the siege of joyous guard.

#scribbles#arthuriana#medieval literature#thomas malory#le morte darthur#le morte d'arthur#sir urry of the mount#sir lavain#in terms of urry’s wounds/scars#i imagine they healed hypertrophically/maybe even keloid#with an excess of scar tissue given how long they were trying to heal for#so they still cause him problems#especially as i imagine a couple would be near his joints#given the areas most likely to get actually wounded as opposed to bludgeoned#are those near the joints ie weak points of the armour#places where it was only mail no plate#oops i forgot to put scars on lavain#but i imagine he has a few too

1 note

·

View note