#museum access

Note

I'm really sorry to bother you, but I've been thinking about studying Museology and have read a lot of your posts (and those of people you've reblogged), and a few of those have been about the ethics of displaying corpses versus in some cases reburying them (which sounds like a very interesting dilemma considering that {in the opinion of someone who doesn't know a lot about museums} museums often are about preserving artifacts) - how often do questions like these come up? Can you avoid them?

not a bother at all dear nerd.

to quote a curator i used to work for 'people don't learn from bodies'

she was speaking about mummified human remains - i am not going to call them corpses as that is too clinical for what museums do. mummified human remains are somebody's ancestor. somebody's grandfather/mother/auntie/cousin/etc. all it takes for me to see the ethical quandary is to question if i would want my own grandmother displayed in a case in 100 years. - the answer is no i would want her body to remain in private for rest until she becomes earth again.

what that curator was talking about is how the macabre tends to shock and fascinate many guests without them questioning or learning anything new from the display. a museum that did it very badly had a human head on a stick with interpretation that said something like 'do you think i'm scary'. i can't tell you what else was in that gallery because there was a human being on a stick there. this institute has since re-displayed their human remains much more ethically - in a gallery off to one side with notices on the doors about the ancestors resting there.

from the position of museums having human remains will always change the landscape of the gallery. your display will become about the remains instead of about the culture they are taken from. you will always have issues with originating communities wanting their ancestors back - repatriation 101 - and they will be right to demand their return. they change the landscape of education in the gallery and more than that.

on the other side of the coin is the issue of consent. consent is not just for the bedroom. we as museum guests do not consent to walking into a random gallery and being confronted by a human head on a stick. we just don't. not all visitors would necessarily have an issue with that but i know one woman who had nightmares for years after visiting that gallery.

culturally speaking, not everyone is blase about human remains, many cultures disallow viewings and many parents do not want to have to explain to their children what death is in the middle of a museum. taking away the cultural context of the humans on display, there is still many many cultural issues with their display.

one way to get around that particular thorn, is to put up notices. to incorporate consent into the gallery space. and to make it an optional space. that is to say, in order to get through the whole exhibit from start to finish a guest does not have to go through the gallery with ancestral remains in it. instead they can consent to see a little bit more off to the left in a side gallery if they want to.

that does not deal with the cultural requirements of the human being on display - let alone their personal wishes. one of the cultural requirements for Egyptians is preservation in memory, so some people argue that having a mummy on display in Canada is not bad because people remember that person. this, however, ignores another aspect of Egyptian culture - to die and be burred away from Egypt meant they could not access Egyptian afterlife. therefore that mummy in Canada should be returned post-haste to Egypt.

this actually happened with Ramses the second. he was 'found' in Canada, and repatriated to Egypt. in Egypt he is still in a museum but he is among his grave goods, and among his people - and you have to consent to go into his final resting place.

this is getting away from me...

lets address 'museums are about preserving artifacts'.

yes and no.

the ICOM definition of museum is down to two proposals as of this year

Proposal A

A museum is a permanent, not-for-profit institution, accessible to the public and of service to society. It researches, collects, conserves, interprets and exhibits tangible and intangible cultural and natural heritage in a professional, ethical and sustainable manner for education, reflection and enjoyment. It operates and communicates in inclusive, diverse and participatory ways with communities and the public.

Proposal B

A museum is a not-for-profit, permanent institution in the service of society that researches, collects, conserves, interprets and exhibits tangible and intangible heritage. Open to the public, accessible and inclusive, museums foster diversity and sustainability. They operate and communicate ethically, professionally and with the participation of communities, offering varied experiences for education, enjoyment, reflection and knowledge sharing.

my preference is the first one, but you can see the complex issues we deal with from both of these.

If we were just about the artifacts we would be an antique store.... without prices.

yes museums with collections have a duty of care to those collections - a big part of why it is challenging to repatriate. but that is not our only duty. and there is only ever a fraction of our collection on display - there are too many things to display otherwise. So, even without returning ancestral remains to their living communities, there is no ethical reason to have them on the gallery floor. UNLESS the gallery space is the only climate controlled storage you have... but then you have bigger problems than ancestors on your hands.

please feel free to ask questions always - it is never a bother - and this is a 100 per cent non-judgmental answer. i know tone can be hard through text.

i would appreciate it if some other blogs chimed in with your opinions. i don't have to worry about ancestors in my current or former museums so i am sure i am missing nuance.

#human remains#museums#museum#accessibility#repatriation#museum spaces#museum access#actually autistic#museologist notes#ancestors#originator communities still exist#this took me an hour to write and i still am not happy with it

440 notes

·

View notes

Text

#tiktok#blind#visually impaired#braille#mona lisa#inclusion#inclusivity#accessibility#disabled lives matter#disabled life#disabled#louvre#art museum#museum#louvre museum

89K notes

·

View notes

Text

I work in a museum so I am the last person you want to visit a museum with. Unless you want to hear an endless stream of "there is no way this text had input from the educational team for average visitor clarity" "the old woman next to me complained she couldn't read the didactic panel and she's right, size 20 font simply isn't sufficient for this distance and even I can't read it" and "how does the brand new wing still have coat hooks five and a half feet off the ground in the handicap bathroom stall"

#museums#I bring a certain 'accessibility guidelines suggest 60pt font for a visitor standing or sitting four feet away' that curators don't like#except my curator because she's the best

5K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Details from Arthur Rackham’s illustration "And now they never meet in grove or green," (1908) from A Midsummer Night’s Dream by William Shakespeare

#Arthur Rackham#A Midsummer Night's Dream#William Shakespeare#Shakespeare#1900s#art detail#art details#Cleveland Museum of Art#public domain#open access#creative commons#detail#cropped#Titania#Oberon#art#illustration#vintage#vintage illustration

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

"Young Girl with Squiddle," referred to in some archaic texts as "Bruja Infanta,"¹ is commonly considered a seminal work of the Early Carapacian Revival.² Like a majority of the paintings from this era, the original is assumed to have been lost during the fall of Prospit.³ Only alchemized copies remain today.⁴

#homestuck#jade harley#wrote the caption as a funny little joke and then was confronted w how much of a nightmare museum ethics would be#in a world w easy access to instant perfect copies of everything. is the original even worth anything. how do you determine authenticity!!#good thing all the museums got destroyed#i don't have an excuse for this one i just wanted to draw a girl in a pretty dress. sorry baby jade

6K notes

·

View notes

Note

any recommendations/personal favourites from the image collections to print out and make a wall collage out of? (extra love if it’s not artstor, my uni doesnt have a subscription to that)

I love this question! It very much depends on your personal vibe, but here's a list of every collection designated as open to get you started:

Folger Shakespeare Library

Images from the History of Medicine

Museum of New Zealand - Te Papa Tongarewa

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture

Science Museum Group

Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture

Statens Museum for Kunst-National Gallery of Denmark

The Cleveland Museum of Art

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Wellcome Collection

#i am partial to the metropolitan museum of art but that's just me#jstor#ask#open access#open content#image collections

223 notes

·

View notes

Text

Artemis will disassemble and clean a fountain pen with the same level of intensity as Butler disassembling and cleaning one of his guns.

#artemis fowl#Artemis will just automatically include the upkeep of Butler's his mother's Juliet's and Holly's fountain pens in the upkeep of his own#Holly and Juliet tend not to use their pens often (which they have because Artemis gifted them pens) so Artemis will help whenever they vis#visit. Then with Butler it is largely due to the man not having the habit of building 'frivolous' rituals of care into his day so Artemis w#will care for the pens as Butler does (at the end of it all) adore the devices#with Angeline I feel Artemis is just so wholly dedicated to that kind of small act of care when it comes to his mother#(thinking of him composing a unique ringtone for her calls)#I think Fowl Sr is more of a ballpoint pen or a pencil fellow and Artemis will sometimes include his father in the hobby by cleaning#and repairing pens in his father's study while the man works (so he will have the experience of being included through the upkeep)#Tim does appreciate when Artemis shows off some of the special/exclusive inks he purchases#he finds the beauty of the ink a much more accessible aspect of the hobby#that diane ackerman quote about crying in a museum while looking at a piece of yellow sulfur and thinking about how lucky we are to live on#a planet of a natural yellow that is so marvelously yellow#Artemis will do ink tests (when you get a new ink and experiment with it on good quality paper) when his father is in the room for this rea#reason

119 notes

·

View notes

Text

The (open) web is good, actually

I'll be at the Studio City branch of the LA Public Library tonight (Monday, November 13) at 1830hPT to launch my new novel, The Lost Cause. There'll be a reading, a talk, a surprise guest (!!) and a signing, with books on sale. Tell your friends! Come on down!

The great irony of the platformization of the internet is that platforms are intermediaries, and the original promise of the internet that got so many of us excited about it was disintermediation – getting rid of the middlemen that act as gatekeepers between community members, creators and audiences, buyers and sellers, etc.

The platformized internet is ripe for rent seeking: where the platform captures an ever-larger share of the value generated by its users, making the service worst for both, while lock-in stops people from looking elsewhere. Every sector of the modern economy is less competitive, thanks to monopolistic tactics like mergers and acquisitions and predatory pricing. But with tech, the options for making things worse are infinitely divisible, thanks to the flexibility of digital systems, which means that product managers can keep subdividing the Jenga blocks they pulling out of the services we rely on. Combine platforms with monopolies with digital flexibility and you get enshittification:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/01/21/potemkin-ai/#hey-guys

An enshittified, platformized internet is bad for lots of reasons – it concentrates decisions about who may speak and what may be said into just a few hands; it creates a rich-get-richer dynamic that creates a new oligarchy, with all the corruption and instability that comes with elite capture; it makes life materially worse for workers, users, and communities.

But there are many other ways in which the enshitternet is worse than the old good internet. Today, I want to talk about how the enshitternet affects openness and all that entails. An open internet is one whose workings are transparent (think of "open source"), but it's also an internet founded on access – the ability to know what has gone before, to recall what has been said, and to revisit the context in which it was said.

At last week's Museum Computer Network conference, Aaron Straup Cope gave a talk on museums and technology called "Wishful Thinking – A critical discussion of 'extended reality' technologies in the cultural heritage sector" that beautifully addressed these questions of recall and revisiting:

https://www.aaronland.info/weblog/2023/11/11/therapy/#wishful

Cope is a museums technologist who's worked on lots of critical digital projects over the years, and in this talk, he addresses himself to the difference between the excitement of the galleries, libraries, archives and museums (GLAM) sector over the possibilities of the web, and why he doesn't feel the same excitement over the metaverse, and its various guises – XR, VR, MR and AR.

The biggest reason to be excited about the web was – and is – the openness of disintermediation. The internet was inspired by the end-to-end principle, the idea that the network's first duty was to transmit data from willing senders to willing receivers, as efficiently and reliably as possible. That principle made it possible for whole swathes of people to connect with one another. As Cope writes, openness "was not, and has never been, a guarantee of a receptive audience or even any audience at all." But because it was "easy and cheap enough to put something on the web," you could "leave it there long enough for others to find it."

That dynamic nurtured an environment where people could have "time to warm up to ideas." This is in sharp contrast to the social media world, where "[anything] not immediately successful or viral … was a waste of time and effort… not worth doing." The social media bias towards a river of content that can't be easily reversed is one in which the only ideas that get to spread are those the algorithm boosts.

This is an important way to understand the role of algorithms in the context of the spread of ideas – that without recall or revisiting, we just don't see stuff, including stuff that might challenge our thinking and change our minds. This is a much more materialistic and grounded way to talk about algorithms and ideas than the idea that Big Data and AI make algorithms so persuasive that they can control our minds:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/11/06/attention-rents/#consumer-welfare-queens

As bad as this is in the social media context, it's even worse in the context of apps, which can't be linked into, bookmarked, or archived. All of this made apps an ominous sign right from the beginning:

https://memex.craphound.com/2010/04/01/why-i-wont-buy-an-ipad-and-think-you-shouldnt-either/

Apps interact with law in precisely the way that web-pages don't. "An app is just a web-page wrapped in enough IP to make it a crime to defend yourself against corporate predation":

https://pluralistic.net/2023/08/27/an-audacious-plan-to-halt-the-internets-enshittification-and-throw-it-into-reverse/

Apps are "closed" in every sense. You can't see what's on an app without installing the app and "agreeing" to its terms of service. You can't reverse-engineer an app (to add a privacy blocker, or to change how it presents information) without risking criminal and civil liability. You can't bookmark anything the app won't let you bookmark, and you can't preserve anything the app won't let you preserve.

Despite being built on the same underlying open frameworks – HTTP, HTML, etc – as the web, apps have the opposite technological viewpoint to the web. Apps' technopolitics are at war with the web's technopolitics. The web is built around recall – the ability to see things, go back to things, save things. The web has the technopolitics of a museum:

https://www.aaronland.info/weblog/2014/09/11/brand/#dconstruct

By comparison, apps have the politics of a product, and most often, that product is a rent-seeking, lock-in-hunting product that wants to take you hostage by holding something you love hostage – your data, perhaps, or your friends:

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2021/08/facebooks-secret-war-switching-costs

When Anil Dash described "The Web We Lost" in 2012, he was describing a web with the technopolitics of a museum:

where tagging was combined with permissive licenses to make it easy for people to find and reuse each others' stuff;

where it was easy to find out who linked to you in realtime even though most of us were posting to our own sites, which they controlled;

where a link from one site to another meant one person found another person's contribution worthy;

where privacy-invasive bids to capture the web were greeted with outright hostility;

where every service that helped you post things that mattered to you was expected to make it easy for you take that data back if you changed services;

where inlining or referencing material from someone else's site meant following a technical standard, not inking a business-development deal;

https://www.anildash.com/2012/12/13/the_web_we_lost/

Ten years later, Dash's "broken tech/content culture cycle" described the web we live on now:

https://www.anildash.com/2022/02/09/the-stupid-tech-content-culture-cycle/

found your platform by promising to facilitate your users' growth;

order your technologists and designers to prioritize growth above all other factors and fire anyone who doesn't deliver;

grow without regard to the norms of your platform's users;

plaster over the growth-driven influx of abusive and vile material by assigning it to your "most marginalized, least resourced team";

deliver a half-assed moderation scheme that drives good users off the service and leaves no one behind but griefers, edgelords and trolls;

steadfastly refuse to contemplate why the marginalized users who made your platform attractive before being chased away have all left;

flail about in a panic over illegal content, do deals with large media brands, seize control over your most popular users' output;

"surface great content" by algorithmically promoting things that look like whatever's successful, guaranteeing that nothing new will take hold;

overpay your top performers for exclusivity deals, utterly neglect any pipeline for nurturing new performers;

abuse your creators the same ways that big media companies have for decades, but insist that it's different because you're a tech company;

ignore workers who warn that your product is a danger to society, dismiss them as "millennials" (defined as "anyone born after 1970 or who has a student loan")

when your platform is (inevitably) implicated in a murder, have a "town hall" overseen by a crisis communications firm;

pay the creator who inspired the murder to go exclusive on your platform;

dismiss the murder and fascist rhetoric as "growing pains";

when truly ghastly stuff happens on your platform, give your Trust and Safety team a 5% budget increase;

chase growth based on "emotionally engaging content" without specifying whether the emotions should be positive;

respond to ex-employees' call-outs with transient feelings of guilt followed by dismissals of "cancel culture":

fund your platforms' most toxic users and call it "free speech";

whenever anyone disagrees with any of your decisions, dismiss them as being "anti-free speech";

start increasing how much your platform takes out of your creators' paychecks;

force out internal dissenters, dismiss external critics as being in conspiracy with your corporate rivals;

once regulation becomes inevitable, form a cartel with the other large firms in your sector and insist that the problem is a "bad algorithm";

"claim full victim status," and quit your job, complaining about the toll that running a big platform took on your mental wellbeing.

https://pluralistic.net/2022/02/18/broken-records/#dashes

The web wasn't inevitable – indeed, it was wildly improbable. Tim Berners Lee's decision to make a new platform that was patent-free, open and transparent was a complete opposite approach to the strategy of the media companies of the day. They were building walled gardens and silos – the dialup equivalent to apps – organized as "branded communities." The way I experienced it, the web succeeded because it was so antithetical to the dominant vision for the future of the internet that the big companies couldn't even be bothered to try to kill it until it was too late.

Companies have been trying to correct that mistake ever since. After three or four attempts to replace the web with various garbage systems all called "MSN," Microsoft moved on to trying to lock the internet inside a proprietary browser. Years later, Facebook had far more success in an attempt to kill HTML with React. And of course, apps have gobbled up so much of the old, good internet.

Which brings us to Cope's views on museums and the metaverse. There's nothing intrinsically proprietary about virtual worlds and all their permutations. VRML is a quarter of a century old – just five years younger than Snow Crash:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/VRML

But the current enthusiasm for virtual worlds isn't merely a function of the interesting, cool and fun experiences you can have in them. Rather, it's a bid to kill off whatever is left of the old, good web and put everything inside a walled garden. Facebook's metaverse "is more of the same but with a technical footprint so expensive and so demanding that it all but ensures it will only be within the means of a very few companies to operate."

Facebook's VR headsets have forward-facing cameras, turning every users into a walking surveillance camera. Facebook put those cameras there for "pass through" – so they can paint the screens inside the headset with the scene around you – but "who here believes that Facebook doesn't have other motives for enabling an always-on camera capturing the world around you?"

Apple's VisionPro VR headset is "a near-perfect surveillance device," and "the only thing to save this device is the trust that Apple has marketed its brand on over the last few years." Cope notes that "a brand promise is about as fleeting a guarantee as you can get." I'll go further: Apple is already a surveillance company:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/11/14/luxury-surveillance/#liar-liar

The technopolitics of the metaverse are the opposite of the technopolitics of the museum – even moreso than apps. Museums that shift their scarce technology budgets to virtual worlds stand a good chance of making something no one wants to use, and that's the best case scenario. The worst case is that museums make a successful project inside a walled garden, one where recall is subject to corporate whim, and help lure their patrons away from the recall-friendly internet to the captured, intermediated metaverse.

It's true that the early web benefited from a lot of hype, just as the metaverse is enjoying today. But the similarity ends there: the metaverse is designed for enclosure, the web for openness. Recall is a historical force for "the right to assembly… access to basic literacy… a public library." The web was "an unexpected gift with the ability to change the order of things; a gift that merits being protected, preserved and promoted both internally and externally." Museums were right to jump on the web bandwagon, because of its technopolitics. The metaverse, with its very different technopolitics, is hostile to the very idea of museums.

In joining forces with metaverse companies, museums strike a Faustian bargain, "because we believe that these places are where our audiences have gone."

The GLAM sector is devoted to access, to recall, and to revisiting. Unlike the self-style free speech warriors whom Dash calls out for self-serving neglect of their communities, the GLAM sector is about preservation and access, the true heart of free expression. When a handful of giant companies organize all our discourse, the ability to be heard is contingent on pleasing the ever-shifting tastes of the algorithm. This is the problem with the idea that "freedom of speech isn't freedom of reach" – if a platform won't let people who want to hear from you see what you have to say, they are indeed compromising freedom of speech:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/12/10/e2e/#the-censors-pen

Likewise, "censorship" is not limited to "things that governments do." As Ada Palmer so wonderfully describes it in her brilliant "Why We Censor: from the Inquisition to the Internet" speech, censorship is like arsenic, with trace elements of it all around us:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uMMJb3AxA0s

A community's decision to ban certain offensive conduct or words on pain of expulsion or sanction is censorship – but not to the same degree that, say, a government ban on expressing certain points of view is. However, there are many kinds of private censorship that rise to the same level as state censorship in their impact on public discourse (think of Moms For Liberty and their book-bannings).

It's not a coincidence that Palmer – a historian – would have views on censorship and free speech that intersect with Cope, a museum worker. One of the most brilliant moments in Palmer's speech is where she describes how censorship under the Inquistion was not state censorship – the Inquisition was a multinational, nongovernmental body that was often in conflict with state power.

Not all intermediaries are bad for speech or access. The "disintermediation" that excited early web boosters was about escaping from otherwise inescapable middlemen – the people who figured out how to control and charge for the things we did with one another.

When I was a kid, I loved the writing of Crad Kilodney, a short story writer who sold his own self-published books on Toronto street-corners while wearing a sign that said "VERY FAMOUS CANADIAN AUTHOR, BUY MY BOOKS" (he also had a sign that read, simply, "MARGARET ATWOOD"). Kilodney was a force of nature, who wrote, edited, typeset, printed, bound, and sold his own books:

https://www.theglobeandmail.com/arts/books/article-late-street-poet-and-publishing-scourge-crad-kilodney-left-behind-a/

But there are plenty of writers out there that I want to hear from who lack the skill or the will to do all of that. Editors, publishers, distributors, booksellers – all the intermediaries who sit between a writer and their readers – are not bad. They're good, actually. The problem isn't intermediation – it's capture.

For generations, hucksters have conned would-be writers by telling them that publishing won't buy their books because "the gatekeepers" lack the discernment to publish "quality" work. Friends of mine in publishing laughed at the idea that they would deliberately sideline a book they could figure out how to sell – that's just not how it worked.

But today, monopolized film studios are literally annihilating beloved, high-priced, commercially viable works because they are worth slightly more as tax writeoffs than they are as movies:

https://deadline.com/2023/11/coyote-vs-acme-shelved-warner-bros-discovery-writeoff-david-zaslav-1235598676/

There's four giant studios and five giant publishers. Maybe "five" is the magic number and publishing isn't concentrated enough to drop whole novels down the memory hole for a tax deduction, but even so, publishing is trying like hell to shrink to four:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/11/07/random-penguins/#if-you-wanted-to-get-there-i-wouldnt-start-from-here

Even as the entertainment sector is working to both literally and figuratively destroy our libraries, the cultural heritage sector is grappling with preserving these libraries, with shrinking budgets and increased legal threats:

https://blog.archive.org/2023/03/25/the-fight-continues/

I keep meeting artists of all description who have been conditioned to be suspicious of anything with the word "open" in its name. One colleague has repeatedly told me that fighting for the "open internet" is a self-defeating rhetorical move that will scare off artists who hear "open" and think "Big Tech ripoff."

But "openness" is a necessary precondition for preservation and access, which are the necessary preconditions for recall and revisiting. Here on the last, melting fragment of the open internet, as tech- and entertainment-barons are seizing control over our attention and charging rent on our ability to talk and think together, openness is our best hope of a new, good internet. T

he cultural heritage sector wants to save our creative works. The entertainment and tech industry want to delete them and take a tax writeoff.

As a working artist, I know which side I'm on.

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/11/13/this-is-for-everyone/#revisiting

Image:

Diego Delso (modified)

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Museo_Mimara,_Zagreb,_Croacia,_2014-04-20,_DD_01.JPG

CC BY-SA 4.0

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/

#pluralistic#ar#xr#vr#augmented reality#extended reality#virtual reality#museums#cultural preservation#aaron cope#Museum Computer Network#cultural heritage#glam#access#open access#revisiting#mr#mixed reality#asynchronous#this is for everyone#freedom of reach#gatekeepers#metaverse#technofeudalism#privacy#brick on the face#rent-seeking

185 notes

·

View notes

Text

i really do hope that they put a museum or an equivalent for fanart somewhere in purgatory. if there was, it’d probably have to be in or near the global tasks dropoff to make it equally accessible (or, well, equally inaccessible since it’s such a long hike to global from all the bases).

part of me wants to say they should admin-restrict pvp in the fanart zone but the other part of me wants the admins to leave it up to the players if they wanna allow pvp while looking at fanart. could allow for some dirty plays. (yeah yeah, spawnkilling and raiding bases while no one is online is bad, but killing a member while they’re looking at fanart? that is LOW.)

it could also allow for some goofy ass moments where someone’s being chased around global and they’re low on health or outnumbered so they run into the fanart zone like “HM OH MAN THIS FANART SURE IS NICE WOW LOOK AT ALLLL THIS LOVELY FANART MADE BY THESE FANS IT SURE WOULD BE A SHAME IF SOMEONE KILLED ME RIGHT NOW WHILE IM LOOKING AT THE FANART. MADE BY THE FANS.” and the other players who were chasing them just pace outside the museum entrance like tigers in (outside?) a cage. OR the other players join them in looking at the fanart but the moment they step outside it’s IMMEDIATELY back to killing.

I just think there’s a lot of potential for this.

#qsmp#qsmp purgatory#dont mind me im just rambling#in reality they should prolly give each team a museum so that the museum doesn’t become just a place for players to hide out during pvp-#-instead of a place where the art should be appreciated. and so that the fanart is more accessible.#i just think there’s a lot of potential for a communal fanart zone#neutral area to hang out and look at fanart? sick.

138 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Welcome to Smithsonian Open Access, where you can download, share, and reuse millions of the Smithsonian’s images—right now, without asking. With new platforms and tools, you have easier access to more than 4.5 million 2D and 3D digital items from our collections—with many more to come. This includes images and data from across the Smithsonian’s 21 museums, nine research centers, libraries, archives, and the National Zoo.

What will you create?"

124 notes

·

View notes

Text

image descriptions in the alt.

Yesterday I got really annoyed with one of our cases. Its the first one you see when you step inside the museum, its big it has no shelves, and it is freaking ugly. It had an either hella faded or Very dusty red cloth on the bottom and all the objects felt "shoved in". Every part of it pissed me off.

So I did something about it.

This is what it looked like (I didn't take the best before photos)

its hard to tell but the reddy-brown panel at the back by the hanging jacket is actually a strip of cloth. the other mirror must have broken at some point and they didn't bother repairing it.

I got all the Stuff out carefully. I placed them on top of the 2 cabinets - the one they came out of and the one next to them. Ianto tried REALLY hard to help. He wasn't allowed. he doesn't understand safe object handling.

I did get this photo though.

Ianto IS the display.

After pulling up the red FELT (felt attracts dust and moisture and should Never be used in a museum setting like this) I discovered a gross layer of green carpeting that also shouldn't be there but was glued down.

Next we windexed inside and out. Never use windex or other chemical cleaners in a case if it has objects in it. This one was empty.

As I waited for the windex to dissipate I grabbed our big roll of acid free archival paper and cut off a chunk to replace the RED FELT. By the time I got that situated we had a surprise visit from a local reservation school (no charge for entrance). I was extra glad to be able to hide stand behind the case and show them some of the object that would have been in it. They were young but asked good questions and seemed to enjoy their time.

As they left I finally started placing some objects back in the case. As I did that I copied down the (bad) interpretation and also wrote out a list of interp to add. the new display is roughly split into 2 sections.

1. Object made locally for local Nations

2. Objects made for sale to other Nations or settlers

3. Object not made locally

I also took out a sewing machine and 3 baskets for space reasons. Oh, and a hanger.

This is what it looks like now.

Its only one case and not technically improved much. But, man, it looks better.

#museums#museum#accessibility#museum spaces#museum access#museologist notes#Camel Town#Indigenous art#First Nations#cw Indian#actually autistic#actuallyautistic

308 notes

·

View notes

Text

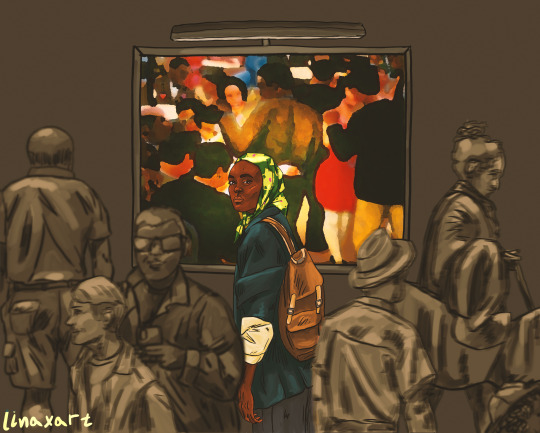

Incognito

with massive thanks to @goldheartedsky who had all the right ideas for this xxxx

#the old guard#nile freeman#tog#tog art#the old guard fanart#nile freeman fanart#nile tog#immortal family#digital art#fanart#sketchbook#Photoshop#accessible art#accessible fanart#artists on tumblr#so! Archibald J. Motley Jr. is a chicagoan black artist which goldie introduced me to#and I'd like to think nile art history freeman would have liked the opportunity to see his work in person#which is why she risked exposure to go to the museum

119 notes

·

View notes

Note

I would like to impart a small hc onto you; the museum is a small, isolated patch of heaven that although V1 can access, they are not entirely sure it's real.

oooooh this is lovely anon....i adore the vaporwave aesthetics of the museum, and so it makes me think of like. this is the form heaven takes when v1 is present in it, something in it digitizing and becoming suitable for a creature sentient but so far from human. v1 is made curious, not just by the surroundings, but by the almost sedative quality to it - the grounds offer plentiful exploration, something to pique its curious mind, but entirely ignore its destructive qualities. there is so much to look for, a little scavenger hunt, and it sees things, so many things, it recognizes in new and interesting ways. it is. calm here. v1, removed from war. no one is here, except for a little cat that appears without it ever seeing it come. v1 doesn't know if it's real. it never stays too long, reality beginning to melt in a much more tangible way than hell, and it can't seem to find it when it tries to show it to gabriel. he just says there is no such place - v1 thinks to take screenshots next time, but they're all black when it tries to share them. gabriel's a bit concerned at this point, but v1 can tell him it's maybe just something he can't do. only v1. unless it can one day manage to drag v2 there.

#i loooove this idea....it's perfect....#like i really enjoy integrating these bonuses in fun ways#like the ask that had the idea of the terminals creating the secret levels in collaboration with hell#so the museum can be a little vaporwave slice of heaven only accessible to machines#or maybe serving as some kind of liminal space....ouughhh#(thank you for letting me incorporate the museum i love it lots)#cake answers#v1

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Forgot to share this really neat exhibit design company I saw at the museum trade show I went to a few weeks ago! They design exhibits to be touchable and interactive in a way that makes them accessible for people with limited vision. Aside from the raised reliefs pictured here, the displays have little metal touch points that when you touch them activate audio clips explaining things more.

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

What makes a good museum? Is it the lighting? The interpretation? The little cafe that serves delicious teas and pastries? Come along with Cosi and I as we chat about our favourite museums and what makes them so engaging!

#its live baby!#please send it to your sister or weird cousin who likes history#museums#british museum#the louvre#accessibility#borghese#cairo museum#Youtube

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here's what our friends at the Cleveland Museum of Art write about these four 17th-century paintings entitled "Scenes of Witchcraft" by Salvator Rosa:

A huge upturn in interest in witchcraft emerged during the 1500s in Europe, but by the middle of the next century - at least among the cultured elite of Florence - a backlash arose against the many accusations of sorcery. Artists and writers explored the topic more out of curiosity and amusement, chief among them the poet, painter, and satirist Salvator Rosa, who examined witchcraft with gusto in numerous poems and works of art, including these four paintings. They show a range witch types - from the beautiful enchantress to the old crone to the male sorcerer - and represent activities commonly associated with black magic - levitation, love potions, devil worship, the invocation of demons, and transformation.

If you think that's awesome, you should browse the museum's collection in JSTOR—lots of great art from a wide variety of cultures and eras, and it's open and free for everyone to view and download!

#witches#witchcraft#warlock#sorcerers#witch#art#painting#italian art#cleveland museum of art#research#jstor#open access#salvator rosa#occult

603 notes

·

View notes