#non-neutral verbs

Text

Baldur's Gate 3 - Non-binary Translation in Spanish

A while back I had mentioned that when I learned how to change language settings for Baldur's Gate 3, I was curious to learn how they would adapt the non-binary [no binario] option into Spanish since Spanish (like many Romance Languages) is very gendered

What I saw actually surprised me a bit

Usually in game translations with different genders, English tends to treat you as a "they" even though it's usually male or female; and in Spanish most of the lines are gendered, or phrased in a very ambiguous way in translation like speaking of your character as una persona "a person" rather than "he" or "she", or "they"

This is one of the first times I've seen the gender neutral -e endings used in an official setting

-

For the purposes of this, and any future posts on this, I decided I would try to play as a non-binary gnome cleric. I should also mention that when you start up the game in Spanish and you do the character customization, everything starts you with the base word (i.e. masculine by default, or possibly agender but looks masculine)... as in you can choose to be elfo "elf", semielfo "half-elf", humano "human", semiorco "half-orc"... choose between bárbaro "barbarian", mago "wizard", brujo "warlock" and so on

My default character creation screen read gnomo, clérigo for "gnome cleric"

But the way your character is addressed by others is what changes

The first NPC you interact with is "Us" a little brain thing you can choose to help. If you do it calls you "friend":

Nosotros: Somos libres. Tenemos nuestra libertad. amigue

Us: We are free. We have our freedom. Friend [nb].

The word used is amigue

For the sake of understanding Spanish grammar, you probably know amigo/a "friend". The G here is a hard G. The gender neutral ending is E... but the combination of GE is pronounced like an H sound in Spanish [la gelatina "gelatin" for example is like "hel-a-ti-na"]. To preserve that hard G sound, you have to add a UE to it... so amigo/a becomes amigue for non-binary

[if you study Spanish this is the exact same grammar you'll see in turning -gar verbs into subjunctive forms; why pagar would turn to pague]

The next person you come across is Lae'zel:

Lae'zel: Tsk'va. No eres une sierve. ¡Vlaakith me bendijo en el día de hoy! Juntes, tal vez podamos sobrevivir.

Lae'zel: Tsk'va. You are no thrall [nb]. Vlaakith blessed me today ["on this day of today"; emphatic]. Together [nb plural], we may (yet) survive.

Interestingly, there's first siervo/a meaning "servant" or "serf" or "thrall"

What I found very interesting was that you have une... un and una being "a" are used for indefinite articles; the non-binary form seems to be une

What threw me off though was seeing juntes... now junto/a is "together" [lit. "joined"] but juntes implies a non-binary plural.

I don't know if this is because in Spanish grammar it would imply that non-binary trumps feminine [the way amigos "friends" could be male+female or multiple male, as opposed to amigas "friends" being all female]... or if it's maybe an error or something else; the game treats Lae'zel as a woman in every other regard so I think it's the first one which is a situation I somehow hadn't considered. I had just assumed it would be juntos ...or juntas if you played female

Next I decided to rescue Gale first because he uses a lot of adjectives/professions and I wanted to see what they looked like:

Gale: No serás clérigue por casualidad, ¿verdad? ¿Médique? ¿Cirujane? ¿Increíblemente hábil con una aguja de tejer?

Gale: You wouldn't happen to be a cleric, right? A doctor/medic? Surgeon? Unbelievably skilled with a knitting needle?

First is clérigo/a "cleric" being used in non-binary as clérigue. Similarly we have médique which is the non-binary médico/a for "medical doctor"

[just like above C turned to QUE to preserve a hard C/K sound; you'll see this with subjunctive and even preterites of -car verbs... why atacar "to attack" will turn to ataqué "I attacked" and ataque in subjunctive... because CE has a soft S sound in Latin America, and can be lisped in Spain]

And next is cirujane... the word cirujano/a is "surgeon"

Finally important note - hábil being "able" or "skilled" is a unisex adjective, so there is no change in any gender - masculine, feminine, or non-binary

*Note: I did miss it but at some point someone used the article le to describe my character. The el and la "the" are the masculine and feminine definite articles; le is non-binary "the" which still catches me by surprise because it looks French to me

-

I've been told since I made the original post that people have seen the non-binary E ending used in other things, but this was special for me to see. I'm curious how the other gendered languages available treated non-binary options

It was a fun surprise for me, especially for some modern day Spanish linguistics in a VERY big modern game, with non-binary word choices being heavily prominent. It's a bit of a learning experience for me

If I find any more fun examples of NB language being used I'll let y'all know as I go

#bg3#baldur's gate 3#spanish#language#langblr#translation#long post#non binary#linguistica#fun with translation

719 notes

·

View notes

Text

Clone language headcanons:

I believe that the clone troopers are a vast, connected, and diverse enough group of people to have developed their own conlang and/or pidgin so that they can communicate clandestinely/privately with one another.

This communication includes subtle and complex body language that non-clones don't notice and don't understand. The clones use both the verbal and body language to pass jokes, commentary, and critiques. The body language is especially crucial because clones are not often given a space for their opinions to be heard. This way, a clone can express their thoughts without having to wait for permission from a higher up (especially a ranked non-clones) to say what they want to say.

One of the most important aspects of the clones language is the pronouns. Clones don't gender their society the way we do. As in, they wouldn't try and split society into groups based on assumed reproductive capability and arbitrary feminine/masculine appearance (like we do IRL)

The clones are a hierarchical society, and their hierarchies are based in rank. When they're not based in rank, it's based on things like merit and experience, but for the time being were just gonna talk about the explicit ranks they have. Because ranking and deference are so important to them, their language reflects that. They have three pronouns, and they are self-referential, meaning that the pronouns of others change based your position relative to them.

Clones above you in rank get one set of pronouns. Clones the same rank as you get another. Clones you outrank get a third. This means that at any given moment, there's a clone for whom all three pronouns are being used to describe them. Take for instance Captain Rex. Cody outranks him, so Cody would call Rex pronoun set C. Captain Keeli and Rex are the same rank, so Keeli would refer to rex with set B (if he was alive RIP 💯🪦🕊️) rex outranks all Shinies and everyone in the 501st, so he'd also be referred to with the final set of pronouns.

I haven't decided yet if the pronouns get conjugated for number yet. I also just realized I'm not sure how a first person plural pronoun would work in a mixed group. Maybe they have a fourth pronoun that ignores rank and is specifically for "us/we" statements.

For verbs and tenses, the clones have only three tenses: simple past, simple present, and simple future. Their unnaturally short lifespans and speedy development get factored into their understanding of time.

The clones have to borrow a lot of words as well from other languages. They have multiple ways to say brother, every term needed for rank and weaponry, probably seven different words for March and a bunch to describe laser fire and specific shades of white. This is because these are the things they saw most in their environment on Kamino and I'm their daily lives. They don't/wouldn't have a word for uncle or aunt, though, because they've never had to refer to someone as such. They might have a word for mother and father.

"brother" Is functionally gender neutral in their language, but when speaking Basic, they'll use "sister" for their clone siblings who are girls/women or otherwise just prefer the term. Clones have a LOT of euphemisms for basically everything around them, but also a lot of teasing or derogatory terms for Shinies. The teasing terms Shinies make up for vets never stick. Of course, as we've already seen in canon, the clones also have a lot of words for helmet.

The clones are HIGHLY secretive about their language. Non-military are the most likely to catch bits and pieces, but military non-clones are actively excluded from access to the language. This includes the Jedi.

As loyal as the clones are to the Republic and the Jedi, they're aware of how tenuous their culture is because of their short lifespans, their restricted lives, and their inability to spread naturally the way other cultures do. So they hold on tight to what they have and resist study. They resist outsiders knowing too much because they value what little privacy they have.

Back to the pronouns for a moment. Theyre 100% accepting of any clones who are trans or nonbinary. That's a personal and sacred as finally choosing a name for oneself. So along the same vein, they respect when someone changes their name.

I think the clones have a Spiritual belief system of sorts, but I haven't really developed it yet. The clones have accents that vary by battalion. There's the strong Kamino accent, and then they pick up the accent of the battalion or company they join. The 501st and Coruscant guard have wildly different accents. Everyone gets teased about how they speak, especially when a battalions been separated from the rest of clone society for a time. The language changes constantly, too.

#ch posts#captain rex#fives#star wars#the clone wars#all the bros#commander cody#clonelang#meta#tcw#clone trooper#clones#swtcw#copy n pasted from twitter

136 notes

·

View notes

Text

as an Irish (we don’t call it “Gaelic”, ever) speaker and a Sunny fan, I thought it would be fun to do a bit of a post about the Irish-language scene in The Gang’s Still in Ireland, because it’s not a scene I see widely discussed but I adore it.

some background. I am not a native Gaeilgeoir (Irish speaker) — my first language is English — but I started learning it age five and have always had very high grades in it and a huge love for it. I was hugely excited about Charlie Kelly being able to read Irish in the previous episode, and even more so when he turned out to be able to speak it.

Colm Meaney, the actor who plays Shelley Kelly, grew up in Ireland and as such would have learned Irish throughout his time in school. (this has been required by law more or less since Irish independence, and it was already quite common before that. nowadays, you can get exemptions for things like dyslexia but otherwise you have to do it.) this is clear in his ease with the language. (I will do a post about where in Ireland Shelley lives at some point, because there aren’t many areas where Irish is the principal language, but that is for another day!) both the actor and the character have easy and good Irish.

Charlie Day, as an Italian-American, obviously does not actually speak the language and presumably learned the lines as a bunch of gibberish sounds. (nonetheless, some of his pronunciations do suggest he had the words written down non-phonetically too.) his delivery of the lines is god damn amazing. Charlie Kelly’s Irish is not remotely American-accented. if I heard someone speaking Irish like that, I’d assume they sounded Irish when speaking English. he doesn’t even sound neutral in Irish; he does actively have an accent (the word choices are more non-regional, not pointing to any of the three distinct dialects, but this makes sense as the same is true of Shelley’s Irish). his pronunciation is so on point and his accent is seriously just a delight to listen to. that’s serious effort to have been put in by an American in a show that routinely makes fun of Irish-Americans! I cannot stress enough how cool it is to see my national language like this and how good a job he does.

as a side note, Charlie Kelly finding Irish much easier to read than English makes total sense! he clearly has dyslexia, as well as intellectual disabilities and autism, so literacy being tricky is totally fair, but is probably being made worse in English by how much of a god damn ridiculous illogical irregular mess the language is. English has around two hundred irregular verbs, and that’s before we even begin to consider the irregularity of its spelling. Irish has eleven irregular verbs, multiple of which are only irregular in one tense. its spelling is entirely consistent and, once the rules are known, any word (pretty much) can be flawlessly pronounced from reading it or flawlessly spelled from hearing it. (I promise Irish names make sense. just not if you try to use English rules on them. the languages are very different!) Irish is one of the most regular languages out there.

so, I thought I’d go through the actual scene. I’m going to put each line, the direct translation, the subtitle provided, and a comment. hopefully this will be interesting to someone other than me!

·—·

“is mise do pheannchara, a Charlie.” (Shelley)

direct translation: “I’m your pen pal, Charlie.”

subtitle provided: “I’m your pen pal, Charlie.”

okay, so they translate “pen pal” two different ways in this scene. the first, used here, is “peannchara”. this is a compound word, much like all those long words you get in German. it’s a perfectly good choice given there is no one standard choice for translating that concept.

“tá brón orm, ach ní thuigim cad atá ráite agat. is féidir liom gibberish a léamh, ach ní féidir liom í a labhairt.” (Charlie)

direct translation: “I’m sorry, but I don’t understand what you’ve said. I’m able to read gibberish, but I’m not able to speak it.”

subtitle provided: “I’m sorry. I don’t understand what you just said. I read gibberish, but I don’t speak it.”

I would slightly disagree with the subtitles here. the “just” bit isn’t expressed at all. in fact, there is no Irish equivalent to that word, and we often just use the English one in the middle of an Irish sentence because of this. however, I expect that RCG (Rob McElhenney, Charlie Day, Glenn Howerton) wrote the subtitles and then handed them to an Irish translator, in which case the translator did a perfectly good job. a couple of notes about the use of “gibberish” here. I love it. firstly, we totally do drop English words into sentences like that. secondly, I really like the choice to use the feminine form of “it” here (that is, to make “gibberish” a feminine noun). all languages except English are feminine nouns in Irish as a rule, so it’s just a lovely detail calling back to the fact that Charlie thinks of it as the gibberish language. also, Charlie Day really does absolutely nail that voiceless velar fricative (the consonant sound in “ach”, as in Scottish “loch” or any number of German words), a sound even many natively English-speaking Irish people are lazy about. good on him.

“níl aon ciall le sin. sé á labhairt anois!” (Shelley)

direct translation: “there’s no sense to that. it’s being spoken now!”

subtitle provided: “that doesn’t make any sense. you’re speaking it now!”

I adore the phrasing of the first sentence here. thoroughly authentic. there are much more obvious ways to phrase it, but this is absolutely what a native speaker might go with. same goes for the second, actually. Colm Meaney says the second line in a sort of shortened way (same idea as how we might turn “do not” into “don’t”) so I’ve struggled slightly with how to directly translate it. interestingly, Shelley categorises “gibberish” as a masculine noun here, but this isn’t really wrong since it doesn’t have an official grammatical gender due to not being an actual Irish word. just a little odd. also, to fit better to the subtitle of the second sentence, I personally would’ve gone with “tá sé á labhairt agat anois” rather than “tá sé á labhairt anois” (the full version of what Shelley says), as this includes the information of by whom it is being spoken.

“’s é mo dheartháir mo chara pinn.” (Charlie)

direct translation: “it’s my brother that’s my pen pal.”

subtitle provided: “but my pen pal is my brother.”

firstly, to be clear, the nuance of the sentence structure here is not captured in either of the above translations because there simply is not an English equivalent to it. secondly, Charlie uses a contraction here by shortening “is é mo dheartháir mo chara pinn”. super cool. also, there’s that other translation of “pen pal”! this one is “cara pinn”, which uses the Irish genitive case (the word mutates instead of using an equivalent of the English word “of”; this case also exists in other languages including Swedish, German, Latin, and Greek). I like this translation very much too. both work! Charlie Day again delivers this line really nicely, even stressing the word for “brother” (and pronouncing its initial consonant mutation absolutely gorgeously)! I am truly very impressed.

“níl aon fhírinne le sin, a mhic. ’s é do chara pinn… d’athair.” (Shelley)

direct translation: “there’s no truth to that, son. it’s your pen pal who is… your father.”

subtitle given: “no son. your pen pal is your… father.”

so, I really disagree with the first sentence of the subtitles here. it works, but also misses a lot of the beautiful nuance that could have been got. I would have gone with “that’s not true, son” or, more likely, “that’s not right, son”. I also disagree with the placement of the ellipsis in the second sentence, as you see (and my frustrations in translating this sentence structure to English continue, as well). however I like the use of “a mhic” (“son”) here, very much. this is a mutated form of “mac”, meaning “son” (yes, as in all of those Irish surnames; they all just basically say who the person is the son of). it carries both meanings that exist in English: an actual son, but also the use of the word as an affectionate way to refer to any man younger than the (usually male) speaker. this is a really nice choice.

·—·

so, yeah! those are my thoughts. feel free to ask any questions you like. I love this scene so much. as well as the reasons above about how good the translation and delivery is, I also love two other main things about this.

firstly, the level of dignity given to the language. Sunny makes fun of Irish-Americans all the time, but doesn’t really do the same to Irish people from Ireland, which I like (I do also wanna talk about Mac and Charlie as members of the Irish diaspora because it is so so interesting, but that is for another day). Irish as a language is not often given dignity, especially in American or English media, so I really love that it isn’t the butt of the joke here.

secondly, that such a significant scene is delivered through this language. just wonderful. after fourteen and a half series, we finally discover the biological father, and the scene cannot be separated from this beautiful language. it just is so perfect.

RCG, and of course Charlie Day in particular, we Gaeilgeoirí (Irish speakers) thank you! our little language made it to the screens of so many people around the world.

I hope this was interesting haha.

·—·

edits: fixed some things I mistyped.

#always sunny#iasip#sunny#it’s always sunny in philadelphia#irish#gaeilge#irish language#charlie kelly#charlie day#colm meaney#rob mcelhenney#glenn howerton#megan ganz#rcg#ireland#irish diaspora

450 notes

·

View notes

Text

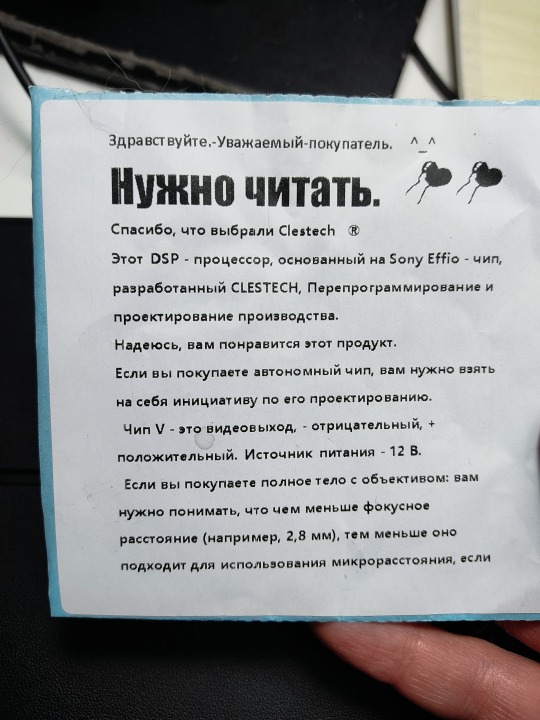

I admire the effort Chinese manufacturers make to communicate in their customers' languages, even if it leads to occasional mistakes. This little instruction on the photo is understandable, but there's a nuance in Russian grammar that might not be obvious to non-native speakers.

The phrase "Нужно читать" (Must read?) sounds natural, but it's a bit general. It's like saying "Humans need air." However, the instruction refers to a specific action - reading this particular text.

To clarify this, we can use the verb "прочитать" (read) which describes a completed action. Here are some options, depending on the desired tone:

Neutral: Пожалуйста, ознакомьтесь с этой инструкцией (Please read this instruction).

Formal: Рекомендуем вам ознакомиться с данной инструкцией перед использованием (We recommend reading this instruction before use).

Emphatic: Обязательно прочитайте эту инструкцию! (Please read this instruction carefully!)

Learning these nuances can help us communicate more effectively across languages, even when encountering small mistakes.

50 notes

·

View notes

Note

re: the grammaticalization of the future tense in english, what is the tense of "Thine kingdom come, thy will be done" in the Lord's Prayer? I thought it'd be future as it's not meant to suggest that the kingdom has come or that it's in the process of developing, but the second bit seems a little imperfecty to me. But also I'm not very good at grammar.

The answer is "no tense".

First of all, it's relevant to note that the grammatical construction in "thy kingdom come, thy will be done" is fossilized in English. This means that it only occurs in certain set phrases (for instance also "long live the king"), but not in ordinary speech.

It's not necessarily the case that fossilized expressions lack internal structure (such as tense)—there is a spectrum from constructions that are completely unproductive and impossible to analyze compositionally in the modern language, like methinks, and those that are semi-productive but archaic, like the one you're asking about here. But certainly it is the case that fossilized constructions need not play by the ordinary rules of a language's grammar, and do not necessarily permit analyses in terms of such. So we should proceed with caution here.

The modern paraphrase of "thy kingdom come" uses a modal verb, may: "may your kingdom come".

To begin with, the use of may neutralizes the distinction between the present and future tenses, because the future tense auxiliary will is also a modal and they cannot co-occur: "*may your kingdom will come", "*your kingdom may will come". Modals also require their argument to be a bare infinitive, and English's other future tense construction, be going to/be gonna, is dubiously grammatical in the bare infinitive form to begin with (at least for me): "*I may be gonna see it", "*I can be gonna see it". So the tense in modal constructions is a neutralized present/future, although I'm not sure what it typically gets called.

But beyond just that, "may your kingdom come" is a type of subjunctive construction, similar to the imperative, as in "go to school!". As such (basically by definition) it is unmarked for tense information entirely. Contrast this non-fronted uses of may, as in "I may have gone", which do permit a past/present contrast.

Anyway, insofar as "thy kingdom come" is an archaic equivalent to "may your kingdom come", it's a subjunctive and thus tenseless.

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

writing advice

what are my qualifications, you ask? i'm a mildly popular writer in the our flag means death fandom (ao3: CartoonMayor), went to writing camps from 12-18, have a creative writing minor, and the unearned confidence of a white person.

DIALOGUE -

"said/says" works 90% of the time. its function is to be invisible. more often than not your dialogue should tell us how something is being said without you have to explain it additionally through extra tags. "Oh no!" he exclaimed. - don't need it. "exclaimed" is implied.

there are other neutral dialogue tags like "asks," "replies," "continues" that work almost as well as said. i still personally recommend using them sparingly, because most of the time they're implied.

if you ARE going to use a non-said/says tag, earn it. it should tell us how someone is saying something that we can't glean from just the dialogue. trust your writing and your readers - show don't tell!

please, please, please mix non-said dialogue tags and adverbs SPARINGLY.

if it's clear who's speaking, you don't need a tag at all

an action can take a tag's place. Ed blinked at him. "What did you say?" vs. "What did you say?" Ed said, blinking at him.

SHOW DON'T TELL -

[overusing] non-said dialogue tags, italics, and adverbs are all because we as writers are desperate to communicate to our readers exactly what we're picturing. but we need to trust them (or edit) and show not tell.

verbs before adjectives before adverbs. which is better: "yells loudly" or "bellows" ? "walks wetly" or "squelches" ?

sometimes telling is good actually!!! don't be spooked if it works in context

OTHER -

epithets are a function of pov. make sure they make sense in that framework. if it's third person omniscient, go nuts. if it's first person or third person limited, ask yourself: in what context do you think of someone as "the other man" or "the blonde" ? one of my tricks if someone doesn't know another character's name is to give them a nickname. "Sparkly Shirt" "Blondie" "Handsome" etc.

don't be scared of names and pronouns. like "said," if you do it right, they'll be invisible that means you can even get away with an occasional "he said to him" if it's still clear who's who!

"then" "suddenly" "finally" "just" "still" - these are all crutch words. there are more i can't think of right now, but trust that if your action is moving forward in a sensical way your readers will keep up without all that padding. if you're going to use them, have a reason to.

description is good (@ myself) but if you can capture how your pov character feels about something that's more valuable than getting every little detail on the page

watch out for repeating words too close together. obviously not the basic ones, but let's say you're writing smut, and you use "moan" three times in two paragraphs. vary it up. (i often cheat and add an "again" to repeated verbs to make them intentional)

and most important of all... all writing advice is subjective and can be thrown in the trash if you don't like it and find something else works for you. ESPECIALLY in fanfic!!!

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

Request Guidelines/Masterlist

I wanted to organize more....

Request Guidlines? Idek if y'all want to request tbh:

REQUESTS ARE: CLOSED

Reader will almost always have gender neutral pronouns, but if I'm in a good mood, I might do gendered labels(boyfriend, girlfriend, etc). Most likely not though.

NO YAN! Y/N

I can write, angst, fluff, yandere, romantic, platonic, and AU's.

You do not have to request yandere, I love writing other stuff too.

I will NOT write NSFW, incest, child x adult(unless platonic), oc x character, character x character, abuse(can be mentioned), or sexual assault(at the most, it'll be a very BREIF mention). Please don't cross my boundaries.

I do not like writing a 'willing' reader x yandere character. It feels gross and like I'm romanticizing the toxicity more than I'm comfortable with. If you request this, I will either delete it, or make it stockholm/give it a not happy ending.

You can request up to 5 people in a fic/headcanon. If it gets too many, I start to struggle and then no one will be happy. if you request more than 5, someone's getting cut.(More than 2 will most likely be made into headcanons as they're quicker.)

If not stated outright, I will decide whether it's in headcanons or fic format. Please be specific if you want it a certain way.

Please don't be mean towards anyone. You can make fun of or yell at me all you want, but don't be a jerk to others.

Don't be scared to request. I love getting requests/asks.

I don't mind dark stuff or horror. I might cut down because it's public, but I will try to keep it as close to your request as possible.

PLEASE BE SPECIFIC. DON'T JUST SAY "_____ X READER", THAT MEANS NOTHING TO ME. If you're stuck, just give me a verb, or look through my prompt list, but please don't just say someone x reader.

Please don't request certain body types. I don't want to write about a skinny reader, or a chubby reader, or a reader with curly hair blah blah blah. It's really hard for me to think of ideas for it, and there's already hundreds of fics out there like that.

I usually won't write a mutant/non-human reader because of personal preference, but if you request like "drider reader who's lived hundreds of years and breathes fire . . . etc", I'm going to delete it. In my mind, that's probably just an OC, and I don't want to write it. Also I just hate writing non-human readers so if you want it to be a non-human reader, it's going to take me a while to get to it. And even then, I'll probably just write it and skip the non-human part.

I reserve the right to refuse any request, and can silently delete a request if I deem it necessary/just because I want to.

If you feel your request is taking too long, message me or send me a ask in my inbox. I'll reply as soon as I can.

What I will write for:

TMNT(all versions but the 1990's, I don't know enough about them. Bayverse and 2007 would probably be iffy as well)

My Hero Academia

Haikyuu!!

The Disastrous Life of Saiki K

Undertale(All Au's, no Deltarune)

Creepypasta(Depends on the character, some I won't write for.)

Five Nights at Freddy's (All games, but not the books)

How to Train Your Dragon

Assassination Classroom

Avatar the Last Airbender

Welcome Home ARG

Danny Phantom

Spiderman: Into the Spiderverse/Across the Spiderverse

The Owl House

Garten of BanBan

Darkwing Duck

The Amazing Digital Circus

Avengers/MCU

Transformers(Prime, Transformers: War on Cybertron Trilogy)

Masterlist:

200 follower prompt list

Writing advice

TMNT

MHA

Subject to change

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

Agent nouns in Mando’a

No, not the 007 kind. I mean different ways to derive words for a “doer” in Mando’a. There are half a dozen different ones. I’ve included some examples, but not an exhaustive list of all the instances these suffixes/derivations appear in the canon dictionary.

In no particular order (because tumblr on mobile doesn’t allow me to drag these into a more logical order):

-ad

As a noun, ad means “a child”. It’s kind of hard to say whether it should be analysed as a suffix or as a part of a compound word in derived words. Whichever way, in derived words the meaning is “person”, somewhat like “man” in English words like foreman, fireman, Englishman, etc. In demonyms, it’s perhaps best translated as “a child of…”. It also appears in other types of nouns and some adjectives, but that’s a story for another time.

In canon, it appears in words such as:

Alor’ad, (n.) ‘captain’ < alor (‘leader’) + ad

Ramikad, ‘commando’ < ram’ika ‘raid’ + ad, “raider”.

Kyramud, ‘assassin’ < kyram (‘death’) + ad (ad dissimilates to -ud)

Mando’ad, (n.) ‘a Mandalorian’, “child of Mandalore” < mando (‘mandalorian’) + ad

+1 non-canon example, since I promised to explain my reasoning for deriving the word for a pilot from sen (‘fly’) + ad > senad (rather than one of the other suffixes): it’s not that I think -ad is the only one or even the most common way to derive a noun for a profession—rather, it’s my observation that pilots seem to hold flying as something that’s more than just a job, and more like a part of their identity. And I wanted the word for a pilot to reflect that. So this one is for all the pilots in my family tree.

-ur

Nominal suffix which seems to denote a doer or an instrument (we also get it in gaanur, ‘hand tool’ < gaan (‘hand’) + ur).

Baar’ur, (n.) ‘a medic’ < baar (‘body’) + ur. My take on this word is that it’s rather like English “physician”, which derives (via French and Latin) from Ancient Greek φυσικός, which means ‘natural’ or ‘physical’. I tend to think that baar’la also means ‘bodily, corporal’ (I’m hardly original in this, my dictionary file lists no less that four authors for baar’la).

Cabur, ‘protector, guardian’ < *cab- (‘protect’) + ur

-ii

A nominal suffix denoting a doer, also used in demonyms (but not professional titles, at least not in the small canon sample). My take on -ii is a neutral agent suffix, much like English -er. It also appears in demonyms, which I’ve written about in here. The tldr is that I think it’s a neutral suffix—but it can be derogatory depending on the context.

Parjii, ‘victor, winner’ < *parj- (‘win’) + -ii

Aruetii, ‘outsider’

Kaminii, ‘Kaminoan’ < Kamino + -ii

-aar

Short. Punchy. I don’t know what else to say.

Chakaar, ‘thief’ < *chak- (‘steal’) + -aar, “stealer, robber”.

Senaar, ‘a bird’ < *sen- (‘fly’) + -aar, “flyer”.

Galaar, ‘a hawk’ < *gal- (‘plunge, plummet, dive’) + -aar. Literally “plummet-er” or “diver”, after its characteristic way of hunting.

-an

This is a fun one. As an independent word, it means ‘all’. As a suffix, it has a couple of different collective senses. When forming an agent noun, the best way I can formulate the meaning is X-an > “one who can all X”.

So cuyan < cuyir (‘to be, exist’) + an is not just any kind of a exister or liver, it’s one who lived through it all, i.e. a survivor.

And a goran < *gorar or possibly *gor + an, is not just any maker or creator, but one who can make everything (or everything that counts, anyway), i.e. a smith, an armourer.

Aran, ‘guard’ < *ar- (my best damn guess is this root means ‘against’) + an, so “one who can (stand) against everything”, probably.

Compound words

I’m still working out the compound word rules in Mando’a so take this analysis with a big heaping of salt. Most compound word titles/agent nouns seem to be a combination of a verb and a noun (like English “woodcutter”) and they don’t need a suffix in addition (“woodcut” rather than “woodcutter”).

First we have a couple of N + V (without the verbal suffix) type compounds. This compound noun type is really common in Mando’a in general.

Gotabor, ‘engineer’ < gota (‘machine’) + bor(ar) (‘work’), “machine-worker”.

Meshurkaan, ‘jeweler’ < meshurok (‘gemstone’) + hokaan(ir) (‘cut’), “gem-cutter”.

The V + N compound word type seems equally well attested:

Tay’haai, ‘archivist, reporter’ < *tay- (‘hold, preserve’) + *haai (probably ‘’), either “hold-truth” or “hold-see(ing, maybe?)”. The problem is, we don’t have a definition for haai. There’s haa’it (‘vision’) and haa’taylir (‘to see’), but no haai. The -i is a noun suffix, so that makes me tentatively place that as a noun.

Al’verde, ‘commander’ < *al- (‘lead’) + verde (‘soldiers’), “soldier-leader” or “lead soldiers”.

Demagol, ‘’ < dem(ar) (‘carve’) + agol (‘flesh’), “flesh-carver” or “carve flesh”.

Others

Sometimes what looks like a verbal suffix -Vr is actually a noun. There are enough of these in the dictionary that it’s either not just zero derivation or it’s a really common one (especially -ar).

Alor, ‘leader’ < *al- (‘lead’) + or

Hibir, ‘student’

Mirci’t, ‘prisoner’. Honestly, this one has a noun suffix that’s otherwise exclusively applied to things, not people. Proceed with caution if you want to take it as an example.

This is my (not exhaustive) analysis based on Traviss’ word list and other works, but I am of course not Karen Traviss and neither do I have access to her notes. If you disagree on something, let me know in the comments or even better, post your own analysis as a rebuttal.

#mandoa#mando’a#mando’a language#mando’a linguistics#ranah talks mando’a#mando'a#mando’a morphology#mando’a analysis

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

How to write in Spanish using neutral language

As a native Spanish speaker, I want to tell you how to use an inclusive language without assuming how a person identifies.

As a gendered language, Spanish has had the use of masculine (Él/el/lo/o) and feminine (Ella/la/a) nouns, just like the use of neutral terms (words like: * persona/médico/profesional/cliente/pareja, etc), and the neo nouns (elle/ele), and this is where it can get confusing.

Elle and ele are used usually for people who identify as non-binary or are gender fluid, and there is nothing wrong with using neo nouns but the term is a label that does not exactly fit everyone and without specifications it can be a little bit exclusive as you don't know if your reader is on the fence regarding how they identify or if they already identify as a man or a woman.

So here is how you have to write:

- Use neutral terms, like the ones mentioned above 🔝*

Other examples: ° "Sonriendo, aceptaste el regalo de la persona enfrente tuyo" - Translation: "Smiling, you accepted the gift from the person in front of you".

° "El anfitrión va a anunciar a la persona que ganó" - Translation: The host is going to announce the winner. ~ Tip: Saying "la persona (que)" alongside a verb/adverb/adjective gives the object or subject whom we are referring into a gender neutral meaning.

- Use neutral possessives:

° "Su risa era contagiosa" - Translation: Their laugh was contagious. ~ Tip: When "su" is written it's like a neutral possessive, like saying "their".

° "El cabello de (character) se mecía en el viento" - Translation: (character)'s hair was flowing in the air.

I hope this will help you.

#langblr#spanish#spanish language#spanish langblr#learn spanish#aprender español#español#idioma español#gender neutral reader#lector de género neutro#lenguaje inclusivo#inclusive language

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some analysis of the overlap between Homestuck chumhandles/trolltags and Rain World iterator names (and pseudonyms)

because what else do you do when you're bored and have Imminent Tasks to do?

To start with, though, some analysis of each individual category to formalize the patterns and "rules" of both naming types!

Chumhandles actually follow a pretty consistent set of rules other than the session-specific ATGC initial conventions! In particular:

It must be either two words exactly, or in the rare edge case of a session leader, one word split between a prefix and a noun (ectoBiologist, carcinoGeneticist). One is too few; three is right out.

No chumhandle is less than four syllables, or more than eight, although one-syllable words are allowed in either half (e.g. twinArmageddons, arachnidsGrip). The longest individual words seem to cap out at 5 syllables (terminally, auxiliatrix).

The most common format is adjective/modifier + noun, with the noun generally being some kind of person or role. (i.e. trickster, biologist, therapist, godhead, gnostic, toreador, geneticist, auxiliatrix, calibrator, culler, gumshoe, gnostalgic, terror) but not always (armageddons, catnip, grip, umbra/ge, testicle, aquarium). The few remaining exceptions either 1) put the noun first (apocalypseArisen), 2) consist of an adverb and adjective instead (terminallyCapricious), or… whatever the fuck Dirk and Tavros had going on (timaeusTestified, adiosToreador).

There is an overall preference for "fancy" and somewhat obscure word choices.

Non-english words are uncommon but acceptable (adiosToreador).

Actually, I'm not sure they even have to be real words either; "gnostalgic" seems to be more of a pun than anything else

For the humans, there tends to be a trend of specific cultural references, generally gnostic or otherwise religious (gardenGnostic, golgothasTerror, timaeusTestified (philosophy but we'll count it), tipsyGnostalgic, arguably turntechGodhead); in trolltags, there's a trend of negative descriptors, violence, and references to the apocalypse.

Iterator names seem to be a little looser overall, probably not helped by the multiple groups of devs not always 100% agreeing re: lore. Thus we can probably say more about acceptable chumhandles than acceptable iterator names, although templates clearly do exist.

Names use whole words and form full phrases, though those phrases don't have to be nouns

Permissible nouns tend to be restricted in category - mostly inanimate natural entities (Moon, Pebble, Sun(s), Straw, Wind, etc) or abstract qualities/behaviors/concepts (Innocence, Harassment)

For natural objects, nouns tend to be simple - one syllable, two at most. More abstract qualities are allowed longer, fancier nouns.

Observed formats/templates include: "[number] [optional adj.] [object]" (Five Pebbles, Seven Red Suns), "[verb]s [preposition] [object]" (Looks to the Moon), "[adjective] [object or abstract quality]" (Unparalleled Innocence, Grey/Chasing Wind, "Erratic Pulse"; in Downpour: Pleading Intellect, Secluded Instinct, Wandering Omen, Gazing Stars), "[noun] of [object]" (Sliver of Straw; in Downpour: Epoch of Clouds). No Significant Harassment is a bit of an outlier but arguably fits group 3, with "No Significant" as the adjective/descriptor part.

The first category of names also seems to overlap the strongest with Ancient naming conventions, so the type of object could speculatively be extended to non-natural objects like bells, beads, etc (though those also seem to be mainly low-tech and "simple" objects), but there's not clear precedent for it.

Overall tone of names is neutral to positive, which makes sense given the context of iterators as the Ancients' "gift to the world" and all that

Looking at these analyses, we can find there is surprisingly small overlap between the two naming conventions! (Although it definitely exists.)

The greatest overlap is probably in iterator names that fit the third template ([adj.] [obj/quality]), most of which can comfortably pass for chumhandles so long as they're just two words and fit the four-syllable minimum. So erraticPulse [EP], unparalleledInnocence [UI], pleadingIntellect [PI] etc scan pretty well.

Chumhandles to iterator names is actually a lot harder, mostly because the range of appropriate nouns for iterator names seems to be narrower overall, and many chumhandles make more explicit cultural or material references which don't translate well into Rain World. Additionally, a lot of trolltags have very negative leaning names, while iterator names tend to be more neutral or even positive in tone. The best few I'd say are maybe Terminally Capricious, Apocalypse Arisen (doesn't strictly fit the naming template but has the vibes~ ok), Undying Umbrage and tentatively Arachnid's Grip (if arachnids can be assumed sufficiently existent for the reference to work), but none of them fully fit the vibes for a proper iterator IMO. Ironically, I've had better luck taking a page out of SBURB Glitch FAQ's book and converting soundtrack titles - Endless Climb, Upward Movement, Plays the Wind, Carefree Action, etc.

This was totally unnecessary but uh. Yeah.

#rain world#homestuck#not art#meta#the broadcast and pearl lore stuff where iterators discuss their actual work and theories etc gives me hugely similar vibes to the-#gamefaqs walkthrough sections of Homestuck and especially fanstuff like the SBURB Glitch FAQ/Replayerverse AU#the fusion of technology and computer science with cosmology and religion in arbitrary and nonsensical ways#so a crossover AU would scan well in either direction I think#anyway i was gonna do a venn diagram but its finals week and im lazy so uh *posts this and does jazz hands*

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

one of my favorite relatively recent internet term developments is people calling themselves "enjoyers." like, "i'm a wrestling enjoyer" or "i'm a games enjoyer," etc. i feel like it has different connotations from calling yourself a "fan" of something, which i think is interesting: being an "enjoyer" seems more easygoing and less lifestyle-committal (you're not in a fandom for that thing, necessarily), but the enthusiasm is no less real. And you can be an enjoyer for anything, not just media ("i'm a daily walk enjoyer," "i'm a honey in tea enjoyer"), and describing oneself as an "enjoyer" feels most natural when it's for something either very general or very specific. And obviously the term "enjoyer" centers joy, which strikes me as being less critical of the thing you're an "enjoyer" of (and there's not necessarily anything wrong with that, it's more just like you're just casually into it and are only into it because it's fun or good, and if it stops being fun or good you won't be into it anymore). i'm pretty sure that the origin stems from the "the noun verber has logged on" types of posts, with "enjoy(er)" being the verb that stuck.

but another interesting observation about "enjoyers" to me is that I've seen people use it to describe what turns them on: e.g., "sweaty armpit enjoyers," "monster sex enjoyers," and when it isn't just sort of a tongue-in-cheek downplaying of how much someone is actually into something (like picture someone sweating profusely and panting and saying "yeah I enjoy this a normal amount"), this language strikes me as affording people to be more open about what might be their kinks or fetishes without requiring those people to commit to crossing some imaginary threshold of calling them kinks and fetishes as such. this is value-neutral to me IMO, like i don't think it's necessarily some abject self-distancing or whatever, since I can think of a couple reasons why people would do that (lack of "real" experience with the thing meaning they only sort of enjoy it in theory, or maybe they're finding a middle ground between non-interest and "especial" interest as they may or may not be easing into it) but again i just find the ways that I see "enjoyer" get used online to be really interesting. i'm something of a linguistic evolution of the word "enjoyer" enjoyer yk?

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nonnulla Indicia Linguae Latinae Idonee Scribendae / Some Hints on Writing Latin Competently

There are many features of Latin grammar and idiom which can be difficult for the modern learner to understand fully because such features have no exact counterparts in English and the Romance languages. Elementary courses on Latin tend to spend little to no time reviewing these seemingly unusual aspects of the Latin language. Fortunately, the student can get some help by consulting the “Preliminary Hints” section of Bradley’s Arnold Latin Prose Composition, and the “Notes on Grammar” and “Various Hints” sections of W. R. Hardie’s Latin Prose Composition. There are several seemingly unusual yet vitally important aspects of the Latin language, though, that these sources do not deal with sufficiently or at all.

In this essay I present some hints that pertain to twelve points wherein the grammar or idiom of those modern languages is misleading or intractable to modern-language speakers who are busy learning Latin composition.

Contents

Latin Does Not Have a “Predicate” Case

Postpositive Particles and Enclitics Have Special Positions

Latin’s Way of Writing “...and I”

Nouns Cannot Be Non-Appositive Modifiers in Latin

Fused Relatives/Correlatives Do Not Exist in Latin

Latin Does Not Use a “Polite Plural” as in Modern Languages

Latin Adverbs and Adverbial Phrases as Attributives

Gender Neutrality (or the Lack of It) in Latin

Word Formation: Nominal Composition and Denominative Verbs

The Difference between Se/Suus and Eius

The Subjunctive by Attraction Is Not Really a Thing in Latin

Adjectives and Adverbs in English, Adverbs and Adjectives in Latin

Sources

1. Latin Does Not Have a “Predicate” Case

In colloquial English we often say, “It’s me” and “That’s him,” where we use the object pronoun forms me and him as subject complements in the predicate of a sentence instead of the subject forms I and he. According to non-colloquial forms of English, we are to say, “It is I” and “That is he.”

Latin, however, does not do this at all, even in its colloquial forms. It has no “predicate” case that differs from the nominative case, and it always uses the same case as the subject for the subject complement. When the verb of the sentence is a linking verb like esse, the case of the subject complement is usually nominative, but in certain situations other cases are involved.

Examples:

Ego sum. (not “Me sum” or “Mihi sum.”)

It’s me.

Ille est. (not “Illum est.”)

That’s him.

Quae sunt illa? (not “Quae sunt illos?” or “Quae sunt illas?”)

What are those?

Esse mihi laeto licet. (not “Esse mihi laetus licet.”)

I am allowed to be happy.

Scio me esse hominem bonum. (not “Scio me esse homo bonus.”)

I know I am a good person.

Deus fio. (not “Deum fio.”)

I am becoming a god.

There are instances in Latin literature, mostly in the plays of Plautus and Terence, where a pronoun in the accusative case follows, or merges with, the interjection ecce even when that pronoun is referring to an individual who serves as the subject of the sentence (e.g., Ecce me, “Here I am”; Eccos exeunt, “Look, here they are coming out”). Someone might suppose that this “ecce + [accusative]” construction is Latin’s own version of the “object me as subject” construction in English, but the truth is that the Latin construction is parenthetic to the rest of its own sentence, and the accusative case is due to its being the object of some form of an implied transitive verb like videre, so: Ecce me = Ecce vide me; Eccos exeunt = Eccos vide, exeunt). The nominative case can also follow the ecce. This construction is also parenthetic to the rest of its own sentence, but it has no implication of the existence of some implied verb like videre (e.g., Ecce ego, “Here I am”).

English speakers who are learning Latin very often make the mistake of writing sentences like “Cornelia est puellam,” instead of the correct Cornelia est puella (“Cornelia is a girl”), partly because of the “object me as subject” construction of colloquial English, and partly because these students are used to seeing the accusative forms of words together with transitive verbs (e.g., Corneliam amo, “I love Cornelia”; eum video, “I see him”).

Memes such as “Me and the Boys” and “Me, Also Me” use the “object me as subject” construction, and so that means that when we translate the English words into Latin, we must use the nominative forms of the Latin pronoun and not some other form like the accusative or ablative me.

We write these meme phrases as:

Ego Puerique/Ego et Pueri

Me and the Boys

Ego, Ego Quoque:

Me, Also Me:

The same goes for the other pronoun forms:

Tu:/Vos:

You:

Is:

Him:

Ea:

Her:

Nos:

Us:

2. Postpositive Particles and Enclitics Have Special Positions

Latin word order is for the most part syntactically freer than that of English, but certain Latin words take specific positions to perform their particular functions. The words of that type which concern us here are postpositive particles and enclitics. A postpositive particle is a word that does not come first in a clause or phrase, and sometimes needs to be translated in English one word earlier than where it appears in the Latin. An enclitic is a word which does not stand by itself, but is added at the end of another word, and therefore all enclitics are by their very nature postpositive particles.

The particles autem (a mark of discourse transition), enim (“for,” introducing a reason), vero (introducing something in opposition to what precedes), quoque (“also,” “too”), quidem (“indeed,” “surely,” giving emphasis, and often has a concessive meaning), and the conjunctive enclitic -que (“and”) and the interrogative enclitic -ne (almost always appearing on the end of the first word of the sentence) are always postpositive, while igitur (“and then,” “then”) and tamen (“nevertheless,” “yet”) generally are.

Ne ... quidem means “not even...” or “not ... either.” The emphatic word or words (represented by the “...”) must stand between the ne and the quidem.

Examples:

Omnes viri mortales sunt. Socrates autem vir est. Ergo Socrates mortalis est.

All men are mortal. Socrates is a man. Therefore, Socrates is mortal.

Pueri autem venerunt.

The boys, however, came./However, the boys came.

Pueri enim venerunt.

For the boys came.

Neutrum vero. Praefero vinum.

Actually, neither. I prefer wine.

Veniant igitur, dum ne nos interpellent.

Let them come then, provided they don’t interrupt us.

Res sane difficilis, sed tamen investiganda est.

Though a difficult question, yet still one that demands investigation.

Senatus Populusque Romanus (not “Senatusque Populus Romanus”)

The Senate and the Roman People

Pueri puellaeque (not “Puerique puellae”)

Boys and girls

Ego Puerique

Me and the Boys

Quodam die chartam piceam habemus quoque.

One day we have tar paper also. (i.e., we, too, will have...)

Tu Quoque (not “Quoque tu”)

You too

Hoc quidem videre licet.

This surely one may see.

Videtene id? (not “Ne videte id?”)

Do you see it?

Mene amas? An eum?

Do you love me? Or him?

Sed ne Iugurtha quidem quietus erat. (not “Sed ne quidem Iugurtha quietus erat.”)

But not even Jugurtha was quiet.

Ingrata patria, ne ossa quidem habebis.

Ungrateful fatherland, you will not even have my bones.

Pay special attention to the positions of these words.

If you want to translate “Also, I did this” in English, resist the urge to write something like “Quoque, hoc feci.” Quoque is never a sentence-modifying adverb like the “Also” in the aforementioned English sentence, and it is so consistently used as a postpositive particle that the “Quoque” in “Quoque, hoc feci” would reasonably be mistaken for either the quoque form of the pronoun quisque or the word quo with the enclitic -que. “Also, I did this” must be translated as Praeterea hoc feci or even Ceterum hoc feci.

3. Latin’s Way of Writing “...and I”

In English we say, “My brother and I” and “the King and I,” with the third person first and the first person last. We seem to do this out of politeness.

Latin, though, does not use that order, and the order which it does use has nothing to do with the expression of politeness. When we talk about the “first person” and the “second person” and the “third person” while discussing Latin sentences, we are using terms which correspond to the order in which we would mention these individuals in a Latin sentence with a finite verb, and that means first person first, second person second, and third person third. We use the same order in mere Latin phrases as well. This means that “You and I” in Latin is Ego et tu. The order then keeps going down the line.

Examples:

Tu et Cicero

You and Cicero

Ego et tu et Cicero

You, Cicero, and I

Ego et Lancelot et Galahad

Lancelot, Galahad, and I

Ego et frater meus

My brother and I

Ego et Rex

The King and I

Note that Latin uses the same order as the colloquial Me and you.

4. Nouns Cannot Be Non-Appositive Modifiers in Latin

While English does distinguish between nouns and adjectives, there is not a hard and fast line between the two categories, and English nouns can act as adjectives even when these words are not the same as the nouns they modify. We can refer to these adjective-like nouns as “non-appositive modifiers.” In the phrases horse feathers and house mother, the two nouns horse and house are not the feathers and the mother, but they modify those nouns, and so are non-appositive modifiers: horse feathers = feathers of the horse variety or equine feathers or feathers on a horse; house mother = mother of the house variety or a mother living in a house or a mother of the house.

Latin cannot do this. There is a hard and fast line between nouns and adjectives in Latin (viz., nouns have a gender, while adjectives assume, or “agree with,” the gender of the noun they are in construction with), and a Latin noun cannot become a non-appositive modifier like its English equivalent can. If we want to use a non-appositive modifier in Latin, we must either use a corresponding adjective or put the word in the genitive:

pennae equinae/pennae equi

horse feathers

mater domestica/mater domūs

house mother

But note what happens if we use the nominative forms of the nouns:

equus pennae

horse and feathers

domus mater

house and mother

When we put the nominative forms of the nouns together next to one another like what we see in each of these two phrases, we end up with an asyndetic phase. (These phrases could also be read as appositives, so that “equus pennae” means “horse, the feathers,” where the horse is the feathers, but since we have established that the corresponding words in the English phrases are not supposed to be appositives, and because these Latin words are imitating a noun phrase rather than being just two linked words, my statement about how each of these is an asyndetic phase still stands.)

Sometimes Latin uses adjectival nouns which are really nouns in apposition, that is, the two nouns refer to the same individual. We can call these words “appositive modifiers.” So, for example, victrices Athenae means “victorious Athens,” and while victrix would normally be a noun meaning “victress” or “the victorious one,” here it is an adjective or an appositive modifier. One could even translate the phrase as “Athens the victress.” Similarly, milites tirones means either “novice soldiers” or “soldiers who are novices.”

Latin’s sharp distinction between nouns and adjectives also applies when words come together to form compound words. The morphological and syntactic features of a word are not nullified simply because it appears within a word, or if it is linked to another word with a hyphen. So, for example, the two words in the compound respublica, “republic,” still have their individual morphological and syntactic features even though they form one word, and therefore since the adjective is agreeing with the noun, each word is declined separately even within that single word: nominative singular respublica, genitive singular reipublicae, accusative singular rempublicam, etc. Another example is modus operandi, “mode of operating,” but this time only the modus is declined while the genitive operandi keeps its form to retain its genitive meaning: nominative singular modus operandi, genitive singular modi operandi, accusative singular modum operandi, etc. All of that means that equus pennae still cannot mean “horse feathers” even if we write it as equuspennae (with no spaces) or equus-pennae (with a hyphen).

Here I point to, and comment on, four specific places which make the mistake of using Latin nouns as non-appositive modifiers.

The “Coronavirus” entry at Latin Wikipedia has an invented “Coronavirus, Coronaeviri” declension (where each of the words corona and virus is declined separately), and this declension is completely wrong because the noun corona cannot be a non-appositive modifier in Latin, and so the compound which uses that declension at best means “corona and virus,” not something like “virus of the corona type.” This “Coronavirus, Coronaeviri” declension therefore behaves like the declension of ususfructus, usūsfructūs, which means “use and enjoyment,” and each of the two words is declined separately. A compound word of corona and virus created through nominal composition would actually be *Coronivirus in Latin. It seems that whoever came up with the name Coronavirus either did not know or did not care that the regular Connecting Vowel in Latin is i for nominal compounds. As it stands, Coronavirus looks like it is a univerbation of the phrase [solari] coronā virus, “virus with a [solar] corona,” which comprises an abbreviated ablative of description and a nominative.

Mark Walker, who translated The Hobbit into Latin (i.e., Hobbitus Ille), rendered the adjective “pitch-black” in Latin as tenebrosa-pix, where he erroneously treated the noun pix as a non-appositive modifier and connected that noun to an adjective with a hyphen. But hyphens do not nullify the morphological and syntactic features of a word, and that means the phrase tenebrosa-pix is exactly the same as the plain, old tenebrosa pix, which really means “dark pitch.” And so, the sentence from Walker’s translation tum tenebrosa-pix erat actually means “then it was dark pitch.” “Pitch-black,” though, can be in Latin piceus, an adjective from pix, or some comparative phrase like tam niger quam pix, “as black as pitch,” or perhaps even piciniger, a neologism that is a nominal compound of pix and niger.

Vox Machina means “Voice and Machine” and not “Voice Machine.” It is a phrase like pactum conventum, which means “bargain and covenant.” Vox is a noun in Latin, and the “voice” in the English phrase “Voice Machine” is not just a noun but also a non-appositive modifier modifying the “Machine,” and so, in order to render “Voice Machine” in Latin, we need to write either Machina Vocalis or Machina Vocis.

This well-known image, which shows stylized depictions of Darth Vader and Luke Skywalker, appears to render “He holds a lightsaber” into Latin as Luxgladium tenet. Luxgladium tenet, however, is just the phrase Lux gladium tenet, which actually means “The light holds the sword”! It looks like whoever wrote the text was trying to create a compound of lux and gladius, but ended up just writing a sentence that is nonsense. (The Latin on this image is pretty awful in general.) I suppose the nominative form of the compound is supposed to be luxgladius, but luxgladius, of course, would mean “light and sword.” The “light” in the word “lightsaber” is a noun and a non-appositive modifier modifying the “sword,” so if we wish to render “lightsaber” in Latin, we need to write ensis luminosus (where ensis is a poetic word for “sword,” and reflects the poetic or fanciful use of “saber”) or ensis luminaris (although luminaris is not a common word in Latin) or, if we wish to use a compound word from lux and gladius, lucigladius.

5. Fused Relatives/Correlatives Do Not Exist in Latin

In English a relative clause and its antecedant can combine into a noun phrase which is called a free relative or a fused relative construction. The resulting what of this fused relative construction is a fusion of both the relative pronoun and its antecedant: what = “that which,” “the thing that.”

Example:

The cats ate what I gave them.

which can be rewritten as:

The cats ate that which I gave them.

Latin does not do this. A Latin relative pronoun, like quod, cannot introduce a noun phrase like the what does in the English sentence above. Nor can it fuse together with its antecedant, since the two words are syntactically discrete. Not only are we unable to pull a “id quod” (“that which”) from this relative pronoun quod in Latin, we are unable to know whether the antecedant should even be id by looking at the relative pronoun!

Latin relative clauses are adjective clauses, and it is important not to treat such clauses as Latin noun clauses for two reasons. First, the noun phrases of that type do not exist in Latin, and second, the language makes a clear distinction between relative clauses and subordinate interrogative clauses, which are noun clauses and are typically called “indirect questions.”

Look at this sentence:

The cats know what I gave them.

You cannot pull a “that which” out of this what because it is interrogative: it represents a variable which the cats could fill in by providing relevant information, and does not represent a combination of an antecedant and a variable which is bound by that antecedant. Latin must express this what by an interrogative which introduces a subordinate interrogative clause.

The two English sentences are therefore translated like this:

Feles id ederunt quod eis dedi. (Relative clause.)

The cats ate what I gave them.

Feles sciunt quid eis dederim. (Interrogative clause.)

The cats know what I gave them.

Memes of the “What She Says, What She Means” format contain phrases which are subordinate interrogative clauses, not relative pronouns, for two reasons. First, the English phrases are noun constructions, and therefore require us to use noun constructions in Latin when we translate the English phrases into Latin. Second, the what represents variables which are subsequently filled in with relevant information, and that relevant information comes after the colons in each of the two phrases.

We translate the two phrases this way:

Quid ea dicat: ...

What she says: ...

Quid ea velit: ...

What she means: ...

Writing “Quod ea dicit:” and “Quod ea vult:” (i.e., relative clauses) would be very wrong because Latin cannot fuse those relatives, and the variable indicated by the English what is filled in with the relevant information after the colons, not some nonexistent antecedant of the relative.

English can also combine correlative words as seen in memes of the “When X / X When” format, which indicate how an individual reacts under a specified circumstance. In such memes, the when looks like it introduces a clause indicating some specified circumstance, but it actually combines that clause with correlative words referring to the individual doing the reacting. Subsequently, the when represents a fusion of itself and some correlative word or phrase like then, at that time, me, or my face when.

Latin does not fuse correlatives like this, either. The phrases tum cum, ego cum, facies mea cum, etc., cannot fuse into a single cum. A Latin word and its Latin correlative are also syntactically discrete, and all of the relevant words must be written out to convey what the English means.

Examples:

Tum cum mater tua cibum tuum favorabilissimum coquit

When your mom cooks your favorite food

Tum cum canis tuus dormiens caudam suam movet

When your dog wags his tail while sleeping

Zeus cum quamlibet feminam videt

Zeus when he sees anything female

Pellicularii Youtube situs cum in duodetricesima secunda pelliculae sunt

Youtubers when they’re 28 seconds into the video

Ego octo annos natus cum minister deversorii me “bonum virum” vocat

8 year old me when the hotel waiter calls me Sir

6. Latin Does Not Use a “Polite Plural” as in Modern Languages

The T–V distinction (or “polite plural”) is the contextual use of different pronouns that exists in some languages and serves to convey formality or familiarity. While modern English does not observe such a distinction, modern Romance languages such as French and Spanish do.

Latin itself, however, does not observe such a distinction. This is true especially for the use of imperatives. If you use a plural form of a Latin imperative, you are specifically addressing more than one person, and that is true if you are making either a general or a specific command for more than one person. Latin does not “default” to the plural when the speaker or writer is uncertain of how many individuals will end up being the recipients of the command. The singular form of a Latin imperative, however, can be used for general commands, which are addressed to no one in particular, and specific commands, which are addressed to a particular person.

Examples:

Cave Canem

Beware the Dog

Sapere Aude

Dare to be Wise

Respice Finem

Look Back at the End

The plural forms of imperatives sometimes appear in quoted texts.

Examples:

Et nunc reges intelligite erudimini qui iudicatis terram.

And now, O ye kings, understand: receive instruction, you that judge the earth.

Manibus date lilia plenis.

Give lilies with full hands.

On a related note, nos and noster sometimes appear instead of ego and meus in Roman letters and familiar speech. In general, the plural forms in such cases have an air of dignity, complacency, and importance. They indicate that the speaker thinks of themself as a “personage.” Cicero frequently uses these plural forms. The regal use of “we,” however, is not known to Latin.

7. Latin Adverbs and Adverbial Phrases as Attributives

English freely uses adverbs and adverbial phrases as attributive modifiers. The phrase man in the moon, for example, comprises a noun, man, and the prepositional phrase in the moon, which modifies that noun like an adjective: man in the moon = a man who is in, or lives on, the moon.

But Latin does not so freely use such words and phrases in that way. When a real adverb or adverbial phrase is used as such in Latin, it is introduced by, or bound to, a verb form, and this means that we often use a relative clause or a participle in Latin where we would use an attributive modifier in English. Thus, we would normally render the phrase “man in the moon” in Latin as vir qui in luna est, vir qui in luna habitat, or vir in luna habitans.

Here are some Latin translations of other English phrases of that type:

Puella Quae Inaurem Margaritiferam Habet/Puella Inaurem Margaritiferam Habens

Girl with a Pearl Earring

Vir Qui Causiam Flavam Gerit/Vir Causiam Flavam Gerens

Man with the Yellow Hat

Fortissimi Qui in Testa Dimidiata Sunt/Fortissimi in Testa Dimidiata Appositi

Heroes in a Half Shell

Rotae Quae in Laophorio Sunt/Rotae ad Laophorium Affixae

The Wheels on the Bus

Simius Qui in Medio Est/Simius in Medio Stans

Monkey in the Middle

Cor Quod Nomine Tuo Inscriptum Est/Cor Nomine Tuo Inscriptum

A Heart with Your Name on It

Pellicula Quae de 10 Numero Est/Pellicula de 10 Numero Tractans

A Video about the Number 10

liber qui e bibliotheca sumptus est/liber e bibliotheca sumptus

the book from the library

At this point we should note that attributive modifiers which resemble adverbs and adverbial phrases sometimes appear in Latin of all periods.

Examples:

At pater infelix, nec iam pater

But the unhappy father, no longer a father

bonos et utilis et e re publica civis

citizens good, useful, and advantageous to the Republic

albo et sine sanguine vultu

with a face white and bloodless

senectutem sine querela

old age without complaint

Ciceronis de philosophia liber

Cicero’s book on philosophy

voluntas erga aliquem

desire to do good to someone

unus e militibus

one of the soldiers

Triumviratum Rei Publicae Constituendae

Commission of Three for the Restoration of the State

Various scholars have hunted down, and commented on, examples of such phrases from Latin literature, especially of so-called “Adnominal Prepositional Phrases” (i.e., prepositional phrases which appear to be used as attributive modifiers which are in construction with nouns). One may inquire why these attributive modifiers have the appearances of adverbial constructions. Perhaps the most obvious way to answer our question is to suggest that these phrases are parts of participial phrases like the vir in luna habitans mentioned above, but the participle in question is typically or usually *sens, the unused present participle of esse, “to be.” According to this suggestion, the phrase At pater infelix, nec iam pater, for example, stands for At pater infelix, nec iam *sens pater, and the phrase bonos et utilis et e re publica civis stands for bonos et utilis et e re *sentes publica civis.

One may object by saying that it is much more parsimonious to suppose that a verbal form like a participle is not implied with these adverbial constructions, but parsimony is irrelevant when we consider that adverbs and prepositional phrases are constructions most typically tied to a verb rather than to a noun, nor would we expect a participle form of esse to show up overly even when we can be sure that its force is felt (as it is in ablative absolute constructions like L. Domitio Ap. Claudio consulibus). If you reject my suggestion, you will get stuck trying to explain why these verb-bound constructions became ostensibly attributive in the first place, and why they are not used ostensibly attributively as often as other, real attributives.

In any event, the fact that many of the Roman authors have used these verb-bound constructions as ostensibly attributive modifiers means that we would be not entirely wrong to imitate that usage: e.g., vir in luna; Puella cum Inaure Margaritifera. Since, however, that usage is not as common as the usage of real attributive modifiers for nouns, and since there is always the potential of construing any of those verb-bound constructions with an actual verb instead of the intended noun, we would be safer to use Latin constructions which contain a relative clause or a participle. An exception to that principle, though, is the use of such verb-bound constructions in well-known Latin phrases and in titles of books and other such media: e.g., Argumentum ad Hominem, “Argument to the Person”; M. Tullii Ciceronis Orationes in Catilinam, “Marcus Tullius Cicero’s Orations against Catiline.”

8. Gender Neutrality (or the Lack of It) in Latin

Modern English has a system whereby natural gender has been assigned to particular nouns and pronouns: masculine words denote male people or animals, feminine words mostly denote female people or animals, and neuter words denote sexless objects. Throughout the years, users of English have invented various gender-neutral pronouns for the language (e.g., thon, xe, ze). In recent times, however, many have taken the generalizing third-person English pronoun they and prescribed it to be used specifically as a gender-neutral or genderless, singular pronoun consciously chosen either for someone whom the user of the word knows or by someone who is rejecting the traditional gender binary. This novel use of they has very much caught on in English-speaking areas, and we see “they/them” prominently displayed in social-media bios, email signatures, and conference name tags.

Gender in Latin is completely different. Latin has at its core a syntactic system of nominal morphology and concord. That is how agreement is possible among nouns, pronouns, and adjectives in the language. Without this system, Latin nominal syntax is altogether incoherent. By convention we refer to this system as “gender.” The hard and fast line between nouns and adjectives in Latin centers around whether a nominal word has a gender (making it a noun or substantive pronoun) or assumes a gender (making it an adjective or adjectival pronoun). Words denoting male people and animals may be masculine, and words denoting female people and animals may be feminine, but Latin’s masculine and feminine gender categories are not based on some sort of essential “male-ness” or “female-ness.” Syntax, not biological reality, ultimately serves as the basis of Latin’s gender system.

Moreover, Latin lacks a gender-neutral or genderless form which is comparable in function to English’s they. All nominal Latin words have a gender, and none can be genderless. A Latin word may not overtly specify a gender, but it always presupposes at least one. The lack of specificity of a gender does not imply the lack of a gender. Third-declension endings like -is and -es and -ex, genitive pronominal forms like eius and huius, and plural pronominal forms like ei and eae, do not behave like they because they are never genderless, and when they refer to people, they are always binary: either masculine or feminine. Latin’s neuter gender is not gender-neutral, and as a matter of fact the only neuter words in Latin which refer to people are words meant to dehumanize or disparage them (e.g., mancipium, “slave”; scortum and prostibulum, “prostitute”). Using neuter-gender pronouns for people in Latin is like using it to refer to a person in English.

Attempts to create gender-neutral language in Latin can very easily fail because they are liable to ignore these basic features of Latin’s gender system and treat the language’s gender system like English’s system of natural gender or the gender systems of the modern Romance languages, which are quite unlike Latin’s system since they lack the neuter gender and cases.

The closest that Latin has to gender-neutral terms are—ironically enough—gendered animal words like passer (“sparrow”), aquila (“eagle”), and vulpes (“fox”). The feminine word aquila, for instance, is always feminine no matter what the reproductive features or individual identity of the particular eagle in question is, so we can write: aquila mas, aquila femina, and aquila nonbinaria. And so, there are indeed “gender-neutral gendered words” in Latin. To our English-speaking ears, “gender-neutral gendered words” may sound absurd, but we should realize that the genders of such nouns exist to satisfy the demands of Latin’s system of morphology and concord.

9. Word Formation: Nominal Composition and Denominative Verbs

English can create compound words from nouns and adjectives simply by joining the words together without changes to those words.

Examples:

egg + head = egghead

cat + girl = catgirl

black + bird = blackbird

Such a process is called nominal composition.

English also can create verbs directly from nouns and adjectives.

Examples:

cash → to cash

weird → to weird

gaslight → to gaslight

These words are called denominative verbs.

Latin can create verbs and compound words from nouns and adjectives as well, but one cannot simply join together words in the same way that we do in English, nor do Latin compound words and verbs come about through random or haphazard development. There are real, coherent processes through which new words arise, and although these processes can be complicated, there are nevertheless some basic ideas to keep in mind.