#slaveowners

Photo

In 1860:

4.5 million people of African descent lived in the United States.

Of these: 4.0 million were enslaved (89%), held by 385,000 slaveowners.

Of these: 3.6 million lived on farms and plantations (half in the Deep South).

Of these: 1.0 million lived on plantations with 50 or more enslaved people.

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

Favoring the British Crown: enslaved Blacks, Annapolis, and the run to freedom [Part 1]

This watercolour sketch by Captain William Booth, Corps of Engineers, is the earliest known image of an African Nova Scotian. He was probably a resident of Birchtown. According to Booth's description of Birchtown, fishing was the chief occupation for "these poor, but really spirited people." Those who could not get into the fishery worked as labourers, clearing land by the acre, cutting cordwood for fires, and hunting in season. Image and caption are courtesy of the Nova Scotia Archives, used within fair use limits of copyright law.

In 1777, William Keeling, a 34 year old Black man ran away from Grumbelly Keeling, a slaveowner on the Eastern Shore of Virginia, which covers a very small area. [1] The Keelings were an old maritime family within Princess Anne County. William, and possibly his wife Pindar, a "stout wench" as the British described her, would be evacuated July 1783 on the Clinton ship from New York with British troops and other supporters of the British Crown ("Loyalists") likely to somewhere in Canada. [2] They were not the only ones. This article does not advocate for the "loyalist" point of view, but rather just tells the story of Blacks who joined the British Crown in a quest to gain more freedom from their bondage rather than the revolutionary cause. [3]

Reprinted from my History Hermann WordPress blog.

Black families go to freedom

There were a number of other Black families that left the newly independent colonies looking for freedom. Many of these individuals, described by slaveowners as "runaways," had fled to British lines hoping for Freedom. Perhaps they saw the colonies as a “land of black slavery and white opportunity,” as Alan Taylor put it, seeing the British Crown as their best hope of freedom. [4] After all, slavery was legal in every colony, up to the 1775, and continuing throughout the war, even as it was discouraged in Massachusetts after the Quock Walker decision in 1783. They likely saw the Patriots preaching for liberty and freedom as hypocrites, with some of the well-off individuals espousing these ideals owning many humans in bondage.

There were 26 other Black families who passed through Annapolis on their way north to Nova Scotia to start a new life. When they passed through the town, they saw as James Thatcher, a Surgeon of the Continental Army described it on August 11, 1781, "the metropolis of Maryland, is situated on the western shore at the mouth of the river Severn, where it falls into the bay."

The Black families ranged from 2 to 4 people. Their former slavemasters were mainly concentrated in Portsmouth, Nansemond, Crane Island, Princess Ann/Anne County, and Norfolk, all within Virginia, as the below chart shows:

Not included in this chart, made using the ChartGo program, and data from Black Loyalist, are those slaveowners whose location could not be determined or those in Abbaco, a place which could not be located. [5] It should actually have two people for the Isle of Wight, and one more for Norfolk, VA, but I did not tabulate those before creating the chart using the online program.

Of these slaveowners, it is clear that the Wilkinson family was Methodist, as was the Jordan family, but the Wilkinsons were "originally Quakers" but likely not by the time of the Revolutionary War. The Wilkinson family was suspected as being Loyalist "during the Revolution" with “Mary and Martha Wilkinsons (Wilkinson)... looked on as enemies to America” by the pro-revolutionary "Patriot" forces. However, none of the "Wilkinsons became active Loyalists." Furthermore, the Willoughby family may have had some "loyalist" leanings, with other families were merchant-based and had different leanings. At least ten of the children of the 26 families were born as "free" behind British lines while at least 16 children were born enslaved and became free after running away for their freedom. [6]

Beyond this, it is worth looking at how the British classified the 31 women listed in the "Book of Negroes" compiled in 1783, of which Annapolis was one of the stops on their way to Canada. Four were listed as "likely wench[s]" , four as "ordinary wench[s]", 18 as "stout wench[s]", and five as other. Those who were "likely wench[s]" were likely categorized as "common women" (the definition of wench) rather than "girl, young woman" since all adult women were called "wench" without much exception. [7] As for those called "ordinary" they would belong to the "to the usual order or course" or were "orderly." The majority were "stout" likely meaning that they were proud, valiant, strong in body, powerfully built, brave, fierce, strong in body, powerfully built rather than the "thick-bodied, fat and large, bulky in figure," a definition not recorded until 1804.

Fighting for the British Crown

Tye Leading Troops as dramatized by PBS. Courtesy of Black Past.

When now-free Blacks, most of whom were formerly enslaved, were part of the evacuation of the British presence from the British colones from New York, leaving on varying ships, many of them had fought for the British Crown within the colonies. Among those who stopped by Annapolis on their way North to Canada many were part of the Black Brigade or Black Pioneers, more likely the latter than the former.

The Black Pioneers had fought as part of William Howe's army, along with "black recruits in soldiers in the Loyalist and Hessian regiments" during the British invasion of Philadelphia. This unit also provided "engineering duties in camp and in combat" including cleaning ground used for camps, "removing obstructions, digging necessaries," which was not glamorous but was one of the only roles they played since "Blacks were not permitted to serve as regular soldiers" within the British Army. While the noncommissioned officers of the unit were Black, commissioned officers were still white, with tank and file composed mainly of "runaways, from North and South Carolina, and a few from Georgia" and was allowed as part of Sir Henry Clinton's British military force, as he promised them emancipation when the war ended. The unit itself never grew beyond 50 or go men, with new recruits not keeping up from those who "died from disease and fatigue" and none from fighting in battle since they just were used as support, sort of " garbage men" in places like Philadelphia. The unit, which never expanded beyond one company, was boosted when Clinton issued the "Phillipsburgh Proclamation," decreeing that Blacks who ran away from "Patriot" slavemasters and reached British lines were free, but this didn't apply to Blacks owned by "Loyalist" slavemasters or those in the Continental army who were "liable to be sold by the British." In December 1779, the Black Pioneers met another unit of the same type, was later merged with the Royal North Carolina Regiment, and was disbanded in Nova Scotia, ending their military service, many settling in Birchtown, named in honor of Samuel Birch, a Brigadier General who provides the "passes that got them out of America and the danger of being returned to slavery." Thomas Peters, Stephen Bluke, and Henry Washington are the best known members of the Black Pioneers.

The Black Brigade was more "daring in action" than the Black Pioneers or Guides. Unlike the 300-person Ethiopian Regiment (led by Lord Dunmore), this unit was a "small band of elite guerillas who raided and conducted assassinations all across New Jersey" and was led by Colonel Tye who worked to exact "revenge against his old master and his friends" with the title of Colonel a honorific title at best. Still, he was feared as he raided "fearlessly through New Jersey," and after Tye took a "musket ball through his wrist" he died from gangrene in late 1780, at age 27. Before that happened, Tye, born in 1753, would be, "one of the most feared and respected military leaders of the American Revolution" and had escaped to "New Jersey and headed to coastal Virginia, changing his name to Tye" in November 1775 and later joined Lord Dunmore, The fighting force specialized in "guerilla tactics and didn’t adhere to the rules of war at the time" striking at night, targeting slaveowners, taking supplies, and teaming up with other British forces. After Tye's death, Colonel Stephen Blucke of the Black Pioneers replaced him, continuing the attacks long after the British were defeated at Yorktown.

After the war

Many of the stories of those who ended up in Canada and stopped in Annapolis are not known. What is clear however is that "an estimated 75,000 to 100,000 black Americans left the 13 states as a result of the American Revolution" with these refugees scattering "across the Atlantic world, profoundly affecting the development of Nova Scotia, the Bahamas, and the African nation of Sierra Leone" with some supporting the British and others seized by the British from "Patriot" slaveowners, then resold into slavery within the Caribbean sea region. Hence, the British were not the liberators many Blacks thought them to be.Still, after the war, 400-1000 free Blacks went to London, 3,500 Blacks and 14,000 Whites left for Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, where Whites got more land than Blacks, some of whom received no land at all. Even so, "more than 1,500 of the black immigrants settled in Birchtown, Nova Scotia," making it the largest free Black community in North America, which is why the "Birchtown Muster of Free Blacks" exists. Adding to this, these new Black refugees in London and Canada had a hard time, with some of those in London resettled in Sierra Leone in a community which survived, and later those from Canada, with church congregations emigrating, "providing a strong institutional basis for the struggling African settlement." After the war, 2,000 white Loyalists, 5,000 enslaved Blacks, and 200 free Blacks left for Jamaica, including 28 Black Pioneers who "received half-pay pensions from the British government." As for the Bahamas, 4,200 enslaved Blacks and 1,750 Whites from southern states came into the county, leading to tightening of the Bahamian slave code.

As one historian put, "we will never have precise figures on the numbers of white and black Loyalists who left America as a result of the Revolution...[with most of their individual stories are lost to history [and] some information is available from pension applications, petitions, and other records" but one thing is clear "the modern history of Canada, the Bahamas, and Sierra Leone would be greatly different had the Loyalists not arrived in the 1780s and 1790s." This was the result of, as Gary Nash, the "greatest slave rebellion of North American slavery" and that the "high-toned rhetoric of natural rights and moral rectitude" accompanying the Revolutionary War only had a "limited power to hearten the hearts of American slave masters." [8]

While there are varied resources available on free Blacks from the narratives of enslaved people catalogued and searchable by the Library of Virginia, databases assembled by the New England Historic Genealogical Society or resources listed by the Virginia Historical Society, few pertain to the specific group this article focuses on. Perhaps the DAR's PDF on the subject, the Names in Index to Surry County Virginia Register of Free Negroes, and the United Empire Loyalists Association of Canada (UELAC) have certain resources.

While this does not tell the entire story of those Black families who had left the colonies, stopping in Annapolis on the way, in hopes of having a better life, it does provide an opening to look more into the history of Birchtown, (also see here) and other communities in Canada and elsewhere. [9]

© 2016-2023 Burkely Hermann. All rights reserved.

#british crown#british rule#british royalty#annapolis#enslaved people#enslavement#black history#nova scotia#birchtown#fisheries#slaveowners#american revolution#revolutionary war#slavery#book of negroes#1800s#1780s#colonel tye#lord dunmore#canada#loyalists

4 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Show proper respect to everyone, love the family of believers, fear God, honor the emperor. Slaves, in reverent fear of God submit yourselves to your masters, not only to those who are good and considerate, but also to those who are harsh. For it is commendable if someone bears up under the pain of unjust suffering because they are conscious of God.

1 Peter 2:17-19 NIV (2011)

#bible verse#government#surrender#humility#christian living#leaders#leadership#slaves#slaveowners#slavery#your life is a testimony#respect#reverence#love your enemies#fear of the Lord#oppression#endurance#heavy burdens#suffering#1 peter 2

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

This Week’s Story!

#time travel#don’t call it time travel#dcitt#nazis#slaveowners#sooners#everybody gets what’s coming to them#eventually#but should they?#hard to know#buchenwald#concentration camp#plantation#land run#land theft I should say

0 notes

Text

Nathaniel Packard's role in the odious slave trade

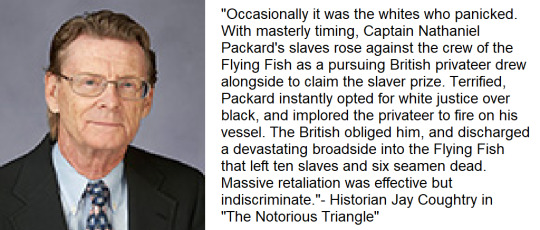

Page 158 of Coughtry's well-known 1981 book, Rhode Island and the African Slave Trade, 1700-1807 . He currently teaches at University of Nevada in Las Vegas.

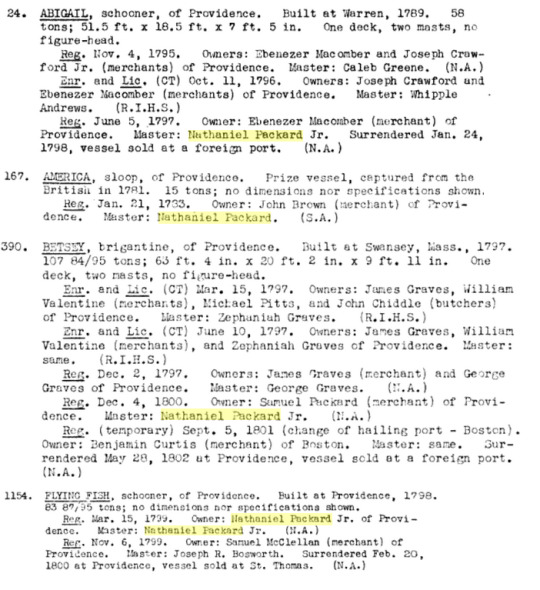

Happy Black History Month! Slave trading runs in the Packard family as I've noted on this blog before. This article was a tough one to write because there are TWO Nathaniel Packards! While I tried to ask about this on /r/AskHistorians and received no reply, [1] I am operating with the educated assumption that the slave trading shown in the 1790s was from Nathaniel Packard, Jr., not his father, of the same name, Nathaniel Sr., as he will be called herein to distinguish from his son, who was the father of Samuel. I would further like to point out that Nathaniel Jr.'s mother was part of the Sterry family, and her first cousin, Cyprian, is the same one who Samuel worked with as a slave trader! [2] Not really a coincidence if you think about it.

Some may ask, how can you be so sure that this is the right Nathaniel? What if Nathaniel Sr. was the one involved in the trade of human beings? For one, I found out that Nathaniel Sr. was born in 1730, died in 1809 while his wife "Nabby" Abigail, was born in circa 1734, and she came to live with this Nathaniel in 1752, at age 18. [3] Her death in 1819, has not been confirmed. Nathaniel Sr. had a child with Abigail in 1769 (at age 39) named Elizabeth, in 1775 (at age 45) a child named Polly, and his child Nehemiah got married in 1777. [4] Furthermore, he probably wasn't engaged in slave trading in the 1790s, due to his age. After all, in 1790, Nathaniel Sr. would have been 61, and in 1799, he would have been 70. That seems a little old to be a captain of a ship, with anecdotal evidence suggesting that captains retired between 53 and 62. [5] I wish my evidence was stronger, but I decided to go with this article anyhow.

We do know that Nathaniel, my 2nd cousin eight times removed according to FamilySearch's "View my relationship" algorithm, was a captain, participating in the Revolutionary War, and reportedly having a similar career to his son, Samuel, owning land on North Main, Howard, and Try Streets in Providence. He was a master privateer during the revolution, captain of a sloop, called the America in 1776, and had a ship he was a captain of, the Sally, captured by the Royal Navy the same year. [6] That, and the story of the America, a ship appearing in thousands of results of the Naval Documents of the American Revolution Digital Edition, is for another day, whether I choose to write about it not. The age of Nathaniel, Jr., my third cousin seven times removed, is disputed. When he died in January 27, 1807, death notices recorded his age as 25, 35, or even 55. [7] At the time of his death, he owned a house on Providence's Main Street, with two houses and other buildings, and in 1801 he is noted as a sea captain, and as marrying a woman named Miss Margaret D. Paddleford in 1800. While he would have been born in 1782 if he was 25 years old in 1807, that means he would have been 15 years old in 1797, it is more likely he was 35 or 55, meaning that he would have been born in 1772 or 1752, although I am leaning more toward his birth in 1772, around the time his other siblings were born, than 1752.

Otherwise, what is known about his personal life is sketchy at best, even having a Find A Grave entry without a photograph of his gravestone. As such, writing about his story and its interconnection with the transatlantic slave trade is important, possibly even revealing more about him as a person. Whether he was a "man of wealth" like his brother, Samuel, or not, the fact remains that uncovering his connection to the slave trade is an important part of recognizing my collective past, the history of enslaved Black people, and much more. This article tries to counter what historians Erica Caple James and Malick W. Ghachem describe as "a still powerful tendency to marginalize or suppress the stories of black lives," with narratives about the past propagated as more marketable than alternatives that try to cut against the grain of “great man” history. [8]

Often Americans see themselves as exceptional people tied together by noble ideals, but this falls apart when history is taught fully and honestly "without omitting facts or telling outright lies" as Margaret Kimberley writes in Prejudential about the racial prejudice manifested by every single US president in history. For Nathaniel, the story starts in 1797. That year, he was the captain of four ships which crossed the Atlantic. The first was the Danish Harriet, which traveled to an unspecified region of Africa, from February to December, bringing with it 53 souls, most of which were men, and selling people in Havana, Cuba. Second was the Providence schooner, Abigail, owned by Ebenezer Macomber. Unlike the Harriet, which Nathaniel owned, this ship began its journey in Rhode Island. Similarly, it traveled to an unspecified region of Africa and sold 53 enslaved peoples, mostly men, in Havana. 11 souls perished during the voyage. [9]

The same year, and into 1798, he was captain, again, of the Harriet, now owned by J de Wint. It traveled once more to Havana, this time with 57 enslaved Black people on board. [10] A pattern emerges when combining data from slave voyages: from 1797 to 1800, Nathaniel, as captain or owner, transported 314 Africans in chains to Havana, Cuba, 85 who died during the Middle Passage, and 6+6 who may have died during the voyage or have a fate unknown, while 10-15 died in a slave revolt as described later in this article. Although after 1794 U.S. slave trade to Cuba was illegal, slave traders still made slave voyages to Havana, and "profited from their own Cuban plantations". This was amidst a societal change in Cuba, which changed from underdeveloped and unpopulated small settlements, ranches, and farms in 1763 to large tobacco and sugar plantations by 1838. This was accelerated by the import of hundreds of thousands of enslaved people during that time period, estimated at 400,000 by Hubert Aimes, benefiting Cuban planters, and a decree in 1789 which allowed foreigners and Spainards to sell as many enslaved people as they wanted in Cuba's ports. Land values rose as landowners, especially those involved in sugar production, gained more power and influence as the "sugar revolution" swept the island, with a 22.8% increase in enslaved people on the island from 1774 to 1827, and the planters depended on Spanish power more than ever to protect their investments. [11]

From pages 8, 60, 136, 360 of Ship Registers and Enrollments of Providence, Rhode Island, 1773-1939, Vol. 1, 1939, I believe the America was owned by his father.

The following year, he was captain, and owner, of the Flying Fish, a schooner from Providence. He co-owned the ship with Sam McClellan. This ship went to an unspecified part of Africa and sold 76 enslaved people in Havana, but they resisted with a "slave insurrection" noted. However, a voyage earlier that year with the same ship was more deadly, as almost half of enslaved people aboard died during the Middle Passage! [12] The ship had a tonnage of 85 tons, higher than some other ships.

It was then that Nathaniel would experience a revolt on the Flying Fish, which was transporting enslaved people. Ten of those on board would revolt, noted in the Newport Mercury. 10-15 enslaved people and 4-5 crewmen were killed in a failed revolt on this private armed vessel. While some sources said this was in 1800, the revolt was in late 1799, in actuality. [13] Coughtry, who I quoted at the beginning of this article, wrote:

Occasionally it was the whites who panicked. With masterly timing, Captain Nathaniel Packard's slaves rose against the crew of the Flying Fish as a pursuing British privateer drew alongside to claim the slaver prize. Terrified, Packard instantly opted for white justice over black, and implored the privateer to fire on his vessel. The British obliged him, and discharged a devastating broadside into the Flying Fish that left ten slaves and six seamen dead. Massive retaliation was effective but indiscriminate. On the few vessels that did experience slave revolts, captors and captives alike paid a high price for the latter's courage.

Nathaniel would be captain of the Betsey in 1800, Eliza in 1803, Minerva in 1794, Juno in 1805, and Dolphin in 1792. By 1800, he was married to Margaret Downs Paddleford, the daughter of well-off physician named Philip Paddleford and Margaret Downe. By the time they married, her mother had been dead or twenty years and Philip had married another woman, Elizabeth Macomber. The same year, friends of a 10-year-old Black male child, Peter Sharp, would testify against Nathaniel to the Providence Council. [14] In later years, in 1801 to 1802, he would be captain of the aforementioned slave ship, the Betsey. Only 94 of the enslaved people made it to the Americas and were sold in Havana, with 24 people perishing during the voyage across the Atlantic. [15] He did this while professing his religious ferment in his last will and testament, bequeathing money and personal property to his children and Margaret:

Will of Nathaniel in 1806, probated in 1807, noting his children and wife. [16]

Nathaniel was creating generational wealth, something which came in part from the trading of enslaved Black people. As Mary Elliott, curator on American slavery for The Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture noted in July 2019, some 12.5 million men, women and children of African descent were forced into the transatlantic slave trade, with the "sale of their bodies and the product of their labor [bringing]...the Atlantic world into being...[with] freedom was limited to maintain the enterprise of slavery and ensure power." She further said that Africans were forcibly migrated through the Middle Passage while the slave trade provided political power, wealth, and social standing for individuals, colonies, nation-states, and the church, while noting that enslaved black people "came from regions and ethnic groups throughout Africa." Although the U.S. international slave trade was made illegal in 1808, domestic slave trade increased, even as illegal slave trading continued internationally, with people such as my ancestor, Captain Samuel Packard, involved in it. What she next is significant to keep in mind:

Slavery affected everyone, from textile workers, bankers and ship builders in the North; to the elite planter class, working-class slave catchers and slave dealers in the South; to the yeoman farmers and poor white people who could not compete against free labor.

Furthermore, slavery itself was built and sustained by "black labor and black wombs", maintaining the economic system itself, with prosperity depending upon the "continuous flow of enslaved bodies", while a campaign of violence was waged against black people that "would rob them of an incalculable amount of wealth" following the end of Reconstruction in the 1870s. [17] Nathaniel, as well as his family, was part of this exploitation and it something that should be recognized, not hidden away or covered up as some people like to do with this history.

Notes

[1] On August 21, I asked "What age did sea captains, in the 18th century, retire?", adding in part "my common sense tells me he wouldn't be sailing a ship at that age and some scattered sources about this, when I did a quick search, did point to that." Unfortunately, a moderator removed the question for asking "basic facts," to which I wasn't happy (obviously), and was directed to another askhistorians thread. I posted a similar version of the question there, asking "Does anyone know what age did sea captains, in the 18th century (more specifically 1790s-early 1800s), retire?" And, just as I expected, I received NO reply. The lesson I took away from this is that you can't trust these forums to respond to you, and sometimes you just have to do the research yourself, with no help from anyone else, sad to say.

[2] Using this family relationship chart and explanatory post, I determined that Cyprian is the son of her uncle. This is because the brother of Abigail's father, Robert (1711-1789), was a man named Cyprian (1707-1772), who had a son named Cyprian (1752-1824), the one, and same, as the slave trader. So, that's the connection. Abigail and Nathaniel later had a daughter named Abigail, who married in 1784, and was named after her. In another interesting antecote, it appears that John Congdon, the father-in-law of 3rd cousin 7x removed, and the father of Abigail, the wife of Captain Samuel Packard, may have been a slave trader as well, as a Congdon is listed as captain of an unnamed slave trading vessel in 1762 and the Speedwell schooner from 1764 to 1765.

[3] Knowles, James D. Memoir of Roger Williams, the founder of the state of Rhode-Island (Boston: Lincoln, Edmands & Co., 1834), 432-433. Reprinted in "Notes on the Grave of Roger Williams," Apr. 20, 1907, Book Notes, Vol. 24, No. 8, p. 59. Relevant quote, reprinted from a letter in The American in 1819: "I am induced to lay before the public the following facts, communicated to me by the late Capt. Nathaniel Packard, of this town, about the year 1808...Captain Packard was son of Fearnot Packard, who lived in a small house, standing a little south of the house of Philip Allen, Esq. and about fifty feet south of the noted spring. In this house Captain Packard was born, in 1730, and died in 1809, being seventy-nine years old...Mrs. Nabby [Abigail] Packard, widow of Captain Packard, who is eighty-five years old, told me, this day, that her late husband had often mentioned the above facts to her; and his daughter, Miss Mary Packard, states, that her father often told her the same... Mrs. Nabby Packard, Nathaniel Packard's widow, told me this day, that she came to live where she now lives, when she was eighteen years old, which was sixty-seven years ago."

[4] "Rhode Island Town Births Index, 1639-1932", database, FamilySearch, 4 November 2020, Nathaniel Packard in entry for Elizabeth Sterry, 1857; "Rhode Island, Town Clerk, Vital and Town Records, 1630-1945," database with images, FamilySearch, 4 November 2020), Nathaniel Packard in entry for Elisabeth Sterry, 22 Nov 1857; citing Death, Providence, Providence, Rhode Island, United States, various city archives, Rhode Island; FHL microfilm 2,022,703; "Rhode Island, Town Clerk, Vital and Town Records, 1630-1945," database with images, FamilySearch, 4 November 2020, Nathanul Packard in entry for Polly Packard, 17 Dec 1858; citing Death, Providence, Providence, Rhode Island, United States, various city archives, Rhode Island; FHL microfilm 2,022,703; "Rhode Island Town Births Index, 1639-1932", database, FamilySearch, 4 November 2020), Nathaniel Packard in entry for Polly Packard, 1858; "Rhode Island Marriages, 1724-1916", database, FamilySearch, 22 January 2020), Nathaniel Packard in entry for Nehemiah Rhoads Packard, 1777.

[5] I'm referring to a 1931 New York Times story titled "37 YEARS AT SEA, CAPTAIN TO RETIRE; SHIP MASTER TO RETIRE" (noted a captain retiring at age 55), a U.S. Navy webpage saying you retire after age 62,and the life of Captain Edward Penniman (1831-1913) described by the National Park Service.

[6] White Jr., George Wylie. “A Rhode Islander Goes West to Indiana (1817-1818),” Rhode Island History, Vol I, No. 1, January 1942, p. 22; Lewisohn, Florence, The American Revolution's Second Front: Persons & Places Involved in the Danish West Indies & Some Other West Indian Islands (University of Texas, 1976), p. 12; "Captain Nathaniel Packard's Account Against the Rhode Island Sloop America, September 30, 1776," American Theatre from September 1, 1776, to October 31, 1776, Vol. 6, via Naval Documents of the American Revolution Digital Edition; "Owners of the Rhode Island Sloop America to Captain Nathaniel Packard, August 21, 1776," American Theatre from September 1, 1776, to October 31, 1776, Vol. 6, via Naval Documents of the American Revolution Digital Edition; "Lists of Prizes Condemned in the Vice Admiralty Court of Antigua, January 14, 1778," American Theatre from January 1, 1778 to March 31, 1778, Vol. 11, via Naval Documents of the American Revolution Digital Edition; "Governor Nicholas Cooke and John Jenckes to Captain Nathaniel Packard, February 3, 1776," American Theatre from January 1, 1776, to February 18, 1776, Vol. 3, via Naval Documents of the American Revolution Digital Edition; "Prizes Taken by British Ships in the Windward Islands, May 1, 1776," American Theatre from April 18, 1776, to May 8, 1776, Vol. 4, via Naval Documents of the American Revolution Digital Edition; "Journal of H.M. Sloop Pomona, Captain William Young, March 11, 1776," American Theatre from April 18, 1776, to May 8, 1776, Vol. 4, via Naval Documents of the American Revolution Digital Edition; "Potential Suspects," Gaspee Virtual Archives, accessed September 26, 2021. He was also said, according to the 1774 RI Colonial Census, to be living in Providence with his family, that year, and have tracts of Land in Providence as early as 1762. As a note on his FamilySearch profile proposes, he may have been involved in the Gaspee Affair in 1772.

[7] According to a note on his FamilySearch profile, a death notice was published in Providence Phoenix (Providence, R.I.), 31 Jan 1807, p. 3, col. 2, has an unclear date of either he was age 25, 35, or 55, with a reprint in the Columbian Centinel (Boston, Mass.), 4 Feb 1807, p. 2, giving his age as 25, the Salem Register (Salem, Mass.), 5 Feb 1807, p. 3, col. 3, giving his age as 35, the Independent Chronicle (Boston, Mass.), 5 Feb 1807, p. 3, giving his age as 25, and Newburyport Herald (Newburyport, Mass.), 6 Feb 1807, p. 3, col. 2, giving his age as 25. See the note for further sources of information beyond this sentence, mainly abstracting from probate records. He was also living in Providence in 1800, according to "United States Census, 1800," database with images, FamilySearch, accessed 26 September 2021, Nathanies Packard Jr, Providence, Providence, Rhode Island, United States; citing p. 211, NARA microfilm publication M32, (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.), roll 45; FHL microfilm 218,680, and his marriage is noted here: "Massachusetts Marriages, 1695-1910, 1921-1924", database, FamilySearch, 28 July 2021, Nathaniel Packard, 1800.

[8] Erica Caple James and Malick W. Ghachem, "Black Histories Matter," Perspectives of History, Sept. 1, 2015, accessed September 26, 2021.

[9] Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade - Database, "Voyage 35224, Harriet (1797)", with entry also in Peoples of the Historical Slave Trade database and another entry here; Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade - Database, "Voyage 36677, Abigail (1797)", with entry also in Peoples of the Historical Slave Trade database.

[10] Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade - Database, "Voyage 35225, Harriet (1798)", with entry also in Peoples of the Historical Slave Trade database.

[11] Franklin Knight, "The Transformation of Cuban Agriculture, 1763-1838" in Caribbean Slave Society and Economy: A Student Reader (ed. Hilary Beckles and Verene Shepherd, New York: The New Press, 1991), 69, 72, 74-78.

[12] Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade - Database, "Voyage 36727, Flying Fish (1799)", with entry also in Peoples of the Historical Slave Trade database; "Voyage 36726, Flying Fish (1799)", with entry also in Peoples of the Historical Slave Trade database and here.

[13] Eric Robert Taylor, If We Must Die: Shipboard Insurrections in the Era of the Atlantic Slave Trade, Vol. 38, 2009, p. 209; Naval Documents Related to the Quasi-war Between the United States and France: From Dec. 1800 to Dec. 1801, United States. Office of Naval Records and Library, 1935, p 397.

[14] U.S., Newspaper Extractions from the Northeast, 1704-1930 for Margaret D Paddleford, Massachusetts, Columbian Centinel, Marriage, Nabor-Ryonson, :Newspapers and Periodicals. American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Massachusetts; Massachusetts, U.S., Compiled Birth, Marriage, and Death Records, 1700-1850 for Margaret Downs Padelford, Taunton; Massachusetts, U.S., Town Marriage Records, 1620-1850, Vital Records of Taunton, Margaret Downs of T. and Nathaniel Packard of Providence, Feb. 12, 1800, in T. Intention not recorded; Massachusetts, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1635-1991 for Philip Padelford, Bristol, Probate Records, Padeford, James - Paine, Sarah, pages 144 and 145; via page 11 of Descendants of Jonathan Padelford, 1628-1858 chart, where it almost looks like Margaret Brown; Children Bound to Labor: The Pauper Apprentice System in Early America, 2011, p. 43.

[15] Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade - Database, "Voyage 36753, Betsey (1802)", with entry also in Peoples of the Historical Slave Trade database.

[16] Will of Nathaniel Packard, 1807, Rhode Island, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1582-1932 for Nathaniel Packard, Providence, Wills and Index, Vol 10-11 1805-1815, Rhode Island, District and Probate Courts.

[17] Of note is what one writer, Nancy Isenberg, argued: that Americans believe in social mobility, but have a "long list of slurs and of terms" for people, and noted that "the discussion of class throughout our history has forced on the centrality of land and land ownership, as well as what I call breeds, or breeding", concepts which come from the British, and notes that another English idea is that "the wealth and the strength of the nation are based on the size of its population" and goes onto say that the English were focused on bloodlines, lineage, and pedigree, even more on inheritance, while saying that class has a specific geography with class-zoned neighborhoods, and stated that convincing people that poor whites are enemies of black Americans is a way to divide people, concluding that "not only are we not a post-racial society, we are certainly not a post-class society."

Note: This was originally posted on Feb. 6, 2023 on the main Packed with Packards WordPress blog (it can also be found on the Wayback Machine here). My research is still ongoing, so some conclusions in this piece may change in the future.

© 2023 Burkely Hermann. All rights reserved.

#packards#slave trade#slavery#enslaved people#black history matters#black lives matter#rhode island#providence#18th century#19th century#havana#cuba#spain#slave revolt#slave rebellion#middle passage#slaveowners#reconstruction#nancy isenberg

0 notes

Text

i am begging you people to get a life

225 notes

·

View notes

Text

I am way too invested in Stucky and probably overreacting about the whole poll thing but I find it so gross that OFMD fans (just the ones who have been overly antagonistic, I'm sure most of you guys are just happy and supporting a ship that you like) have been mocking Stucky fans for shipping something that was never made canon because I think that's genuinely what makes Stucky such a beautiful ship. In the face of homophobia, the homophobia of Steve and Bucky's universe and of ours, thousands of people have found love and beauty and have created entire works of literature and enduring quotes and defined an era of media consumption in the face of the queerbaiting epidemic of the 2010's. I PROMISE YOU, you would not have your queer pirate show without the overwhelming love that fandom spaces showed for queer relationships in the 2010's, and particularly without the love that fans have for Steve and Bucky.

#definitely overreacting#but i don't really care#every ofmd fan i've seen over the past few days has just been so fucking stuck up#no i'm really happy your slaveowners got to kiss#but that doesn't negate the absolutely monumental impact that stucky has had on the fandom spaces YOU now inhabit#we created spaces for ourselves when studios refused to listen and that isn't pathetic#a single quote from a stucky poem has had more impact than your show ever will#don't argue because i promise you can't change my mind on this#marvel#mcu#stucky#stevebucky#bucky barnes#steve rogers#catws#captain america#marvel fanfiction#bucky barnes fanfiction#fanfiction

196 notes

·

View notes

Text

Now that episode 18 of Vinland Saga has aired I can finally talk about one of my absolute favorite character arcs in the farmland arc.

That being Ketil. He is introduced as a "fair" and "kind slavemaster". He doesn't mistreats his slaves, even offering the opportunity to gain back their freedom.

And you can see this in the audience reception of this character. Plenty of people seemed to like him and feel bad for him when he is confronted with challenges.

However, over the course of the season as he gets more screentime, it is revealed that :

Despite Ketil himself being fair to his slaves, his own underlings (farmhands and hired guards) actively mistreat and abuse these slaves. Which at worst shows that he doesn't actually cares about his slaves and at best that he is ignorant to the state of his own farm.

Ketil is scared of his own son (Thorgil). This at first glance might seem entirely reasonable and not Ketil's fault. However, considering that Ketil seems to also fail at raising Olmar it paints a pretty bleak picture of him as a father.

He doesn’t seem to subscribe to the violence craving ideology other norse men do, which by itself might be a point in his favor.

However, the storyline with the kids stealing his grain reveals Ketil is utterly incapable of backing up his beliefs, despite as the patriarch of the family and a wealthy landowner being in the unique position where he actually could implement and enforce his convictions.

Instead he watches woefully his social inferiors (Snake and Pater - his employees, Thorgil - his son, and his wife) decide the fate of these children, a decision that rightfully should be his to make. In the end all of his lamenting about the violence expected of norse men is revealed to being mere selfpity over his own disability to fully embody this social ideal.

This is brought home by one of the mist poignant sequences in the first cours of this season:

Ketil a slavemaster crying in the arms of an his own slave, Arnheid, complaining about his own suffering due to unjust expectations

The young boy he has just beaten brutally to uphold his own fragile image

Thorgil and other man indulging in an excess of food and drink (which is quite ironic considering that the boy was beaten for stealing food to survive)

All of this of course columnates in the most recent episode, when Ketil finally sheds the fragile facade of the generous, jovial Master.

The beating of Arnheid is ultimately the moment we see who Ketil has truely been all along. We seen him obsessed with his own prosperity, continuously seeking to expand it (Thorfinn and Einar's task) and jealously guarding it from outsiders via the guests. He continously buckles under social expectations of what a man is supposed to be and only uses his own distaste for violence to selfishly pet his own ego.

However, in the end he like every other norse men will use violence to hord his wealth (beating a child) and prop up his social standing (story about iron fist). Despite his supposed kindness to slaves like Thorfinn and Einar, he ultimately regards them as his own property.

All of these factors lead to him beating Arnheid, who he ultimately only sees as his posession.

#vinland saga#makoto yukimura#manga#vinland saga season 2#ketil#arnheid#all slaveowners are bad slaveowners#ketil is a perfect examination of#toxic masculinity

263 notes

·

View notes

Note

Your family lore is crazy

we're also (potentially) descended from a man who made evaporative air condioners and improved toilets for trains

#i say potentially because the man is black and his grandparents probably were slaves#meaning it couldve been the slaveowner's name

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kinda crazy how quick people who don't even watch ofmd will jump on the bandwagon of get fucked you guys suck haha glad your show is done! Like??? I genuinely don't understand. Why go out of your way to rain on someone else's parade with clearly no knowledge of the show?

#ofmd#renew as a crew#omfg not people calling it a slaveowners rpf#like what in the fuck#maybe don't blindly regurgitate what you heard from eternally pissed of twitter user no. 19#twitter is an echo chamber of hate most of the time fuelled by a lack of nuance & prejudice & misconception#ANYWAY#I'm living my best life enjoying my little shows with fun stories and ubers of representation written by a diverse writing room#:D#(p.s. just bc people don't devote their online presence to something big and real and serious doesn't mean they're ignoring the problem)#p.s.s. it's not really stede bonnet! it's an actor playing from a script! 😉 wowww

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saw that the omfd billboard thing went the way of dashcon and "all or nothing" and "officer and mr truffles"

Get scammed fuckers

"Big in Japan" by Alphaville ten hours in celebration

#haha fuck you guys get bent fash supporters#from the river to the sea!!!!!#if you give money to slaveowner gaybait show fund spread the wealth you rich idiots#pay a palestinian double what you gave the billboard fund you selfish cunts

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Family secrets, family trees, and family history in Spellbound

On October 13, Libby Copeland wrote an interesting article in Psychology Today about the interest of Americans in genealogy, saying that it has become a cultural phenomenon and a big business, noting her book on the topic, titled The Lost Family: How DNA Testing Is Upending Who We Are. She noted that for much of U.S. history it has been seen as either "a worthy middle-class endeavor" or something to "divide people into a hierarchy of stations based on race and class," which changed in the later 20th century as the pursuit of family history became broader, with more Americans understanding themselves and their ancestors. Copeland also stated that the desire to look backward is sometimes out of a "sense of rootlessness," storytelling, explanation of family traits, and hoping the past can explain the present, while Black people may be "blocked from knowledge of the past by the paucity of records about their enslaved ancestors." She also stated that currently, we look because of a fear of current circumstances with the COVID pandemic, with Copeland stating that the present is time to ask questions, reckon with our past and that many of us are "faced with profound surprises about ourselves and our families, answers to questions we never even realized we were asking." In this post, I'll explore how this has manifested itself in some of my favorite webcomics, Spellbound, by Rose Luxey, otherwise known as "Ronce."

Reprinted from my Genealogy in Popular Culture WordPress blog. Originally published on March 15, 2021.

It begins in issue 86, aptly titled "Family history." One of the protagonists, Eglantine "Egg," comes to the mess hall alongside her roommate Ninon, asks her friend Faustine about what it means that her family is experimenting with magic, "legally speaking." Faustine explains that her family can be traced to the Great Magic Wars, with her father from one of the leading families. Right after that, we see a family tree, as shown below:

Following this, Faustine explains that her ancestors were part of a family which brought destruction in their quest for more power and realizing her connection to that past, that it is not so distant anymore. The parallel I can think of are White people who have slaveowners as ancestors, who dismiss it as far in the past, even though it is part of their heritage, something which should be acknowledged. Egg is disturbed by this, as shown in the next issue of the webcomic, with Faustine admitting it isn't good to read about terrible things her uncle did in the past, and alter beginning to tell her about the different kinds of magic.

Sadly, this seems to be the only time roots or genealogy come up in the webcomic. However, this doesn't mean the webcomic is bad or anything. Rather, it focused on more important issues, interpersonal conflicts, identity crisis, friendship, love, depression, familial neglect, acceptance, and the like. And all of those issues are interconnected with the roots work that each of use do as genealogists. So, in that way, it comes full circle.

© 2021-2023 Burkely Hermann. All rights reserved.

#webcomics#webtoon#spellbound#covid 19#covid19#pandemic#lineage#ancestors#slaveowners#whiteness#magic#roots work#reviews#genealogy#family history

0 notes

Text

now that i can stand to watch the firuze arc without seething and throwing up my hands at how utterly nonsensical its placement in the plot is, i have to wonder just what firuze was thinking every time she was with suleiman. sis was probably rolling her eyes to the back of her head every time he opened his mouth about "love". you think when she returned home she gossiped with her family about his ostentatious flowery over-the-top love poems

#i appreciate firuze as like. one of the only major harem characters not in love with her actual slaveowner#obv her situation is different since she has a home and family to go back to. but still she was playing suleiman like a fiddle#firuze hatun#firuze#sultan süleyman#muhteşem yüzyıl#muhtesem yuzyil#magnificent century#mc tag#i ramble

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Captain Samuel Packard's illegal slave-trading and the cost of a $2,000 fine

ca. 1794, painting by James Earle, at the RISD Museum. "Seated casually in a Windsor chair, Samuel Packard signals his social and professional role in the new republic. The plush drapery, the decorative column, Packard’s fashionable bright-hued waistcoat all suggest that is a man of wealth. The ship in the distance and the spyglass refer to his interests in maritime trade. A merchant and talented mariner, Packard owned 39 vessels that sailed from Providence. Around the time of this portrait, Packard had completed missions abroad for George Washington, so the ships may also allude to Packard’s diplomatic travels." His role as a slave trader is NOT mentioned in this description, although I'm not sure why.

Building on my post in late September, I'd like to focus on how much my third cousin seven times removed, Captain Samuel Packard, who I first wrote about back in July 2021 would have paid had he been convicted of the anti-slave trade law of 1797, which has a fine of 100 Rhode Island pounds per violation, equivalent of one pound per dollar, and the Slave Trade Act of 1794 which carried with it a fee of $2,000. He was not convicted, even though the Providence Abolition Society had petitioned the Attorney General of Rhode Island, Charles Lee, in March 1797, charging that a ship, owned by Cyprian Sterry and Samuel, named the Ann, traveled to the African coast for enslaved people in violation of Rhode Island Law. Pressure from those invested in the slave trade prevented most convictions. While Samuel supposedly signed a pledge saying he would leave the slave trade forever, as I noted in my aforementioned post in July 2021, he retained his wealth and privilege.

In that post, I said that Samuel would have paid a total fine of $2,400 if he had been tried and convicted of his crimes in 1797. I stated that he would be paying $47,900.00, "in terms of real price/real wealth, one of the most accurate measures, tied to CPI, according to Measuring Worth". I'm not sure that is the most accurate measurement. Clearly the fine is not a commodity (consumer goods and services) nor a project (an investment or government expenditure). However, it is closest to income (flow of earnings). As such, the best would be real wage/real wealth, which measures the purchasing power of an income or wealth by its relative ability to by goods and services, as noted by Measuring Worth. That value is $61,100.00 in 2021 values. Still, this would have been probably a small price to pay for Samuel.

If Samuel had continued his slave trading activities, his ships could have been seized by U.S. authorities per a law in 1800. More fundamentally, he was unique in the sense that plantation owners were the main ones who substantially profited from enslaved peoples. The slave trade was relatively profitable, with at least 6% return, although there were maritime and commercial risks. According to Guillame Daudin's analysis of profitability of long-distance trading and slave trading for eighteenth century France, some investors bought small shares in many ships, spreading out their risks, and between voyages, shares in slips could be bought and sold freely. Others calculated that even if slave trading companies didn't profit from a specific voyage, it still led to "extra activities such as shipbuilding or the production of trade goods". Even The Economist stated that slavery was profitable for slaveowners but not for few others. Colonial Williamsburg explained a little more on their website:

A slave voyage was always a risky financial venture for the owners and investors...Also, the nature of trade along the African coast was ever changing, as the desirability and value of particular textile designs and colors, for example, varied month by month and from region to region...The ship captains drafted both experienced and inexperienced sailors, which created risks for the ship owners and investors. Slave ships were, then, dangerous, violent, and disease-ridden. Despite the risks, slave voyages proved to be greatly profitable for their investors. The ship captain faced a paradox, because it was in the crew’s interest to ensure that as many African captives survived as possible in order to be sold to the highest bidder in the Americas. The slavers’ and their investors’ aim was to sell the men, women, and children for the best prices, not to kill or disable them, but the crew often resorted to violence to control and demoralize the captives...Sighting land in the Americas was a relief for the captain and crew but must have brought new uncertainty and fear to those who had survived the Middle Passage. After the captain landed the ship in a port, African survivors were inventoried, fed, scrubbed, and oiled to create a healthier appearance...At every point of this horrific journey, the business of the slave trade and the enslaved individual’s role as commodity was present. Exchange, trade, and profits were the engines of the transatlantic slave trade"

Simply put, Samuel profited off the trade of human beings. As I noted in my previous post, he is equivalent to what we would call a human trafficker today, but was called a slaver or slave trader during the time he was alive.

Note: This was originally posted on Nov. 14, 2022 on the main Packed with Packards WordPress blog (it can also be found on the Wayback Machine here). My research is still ongoing, so some conclusions in this piece may change in the future.

© 2022 Burkely Hermann. All rights reserved.

#packards#slave trade#slavery#black history matters#black lives matter#genealogy#genealogy research#ancestry#lineage#18th century#1790s#wealth#privilege#slaveowners#middle passage#slave ships#human trafficking#slaver#rhode island

0 notes

Text

you are not a newsie from newsies. you are not hamilton from hamilton. this is not a battle or a revolution or something that matters to anybody who has hobbies.

#adina's originals#our flag means death#it’s kinda hilarious seeing them talk about themselves and “their cause” like they’re the yugoslav partisans or something#slaveowner rpf

162 notes

·

View notes

Text

cic. att. 16.1 trans. e-pistulae / lucan, pharsalia 7.645-6 trans. a.s. kline

#AND in both cases a roman senator is like wahh the political situation rn is like slavery :( while being a literal slaveowner#e-pistulae#epistulaeposting#pharsalia#beeps

26 notes

·

View notes