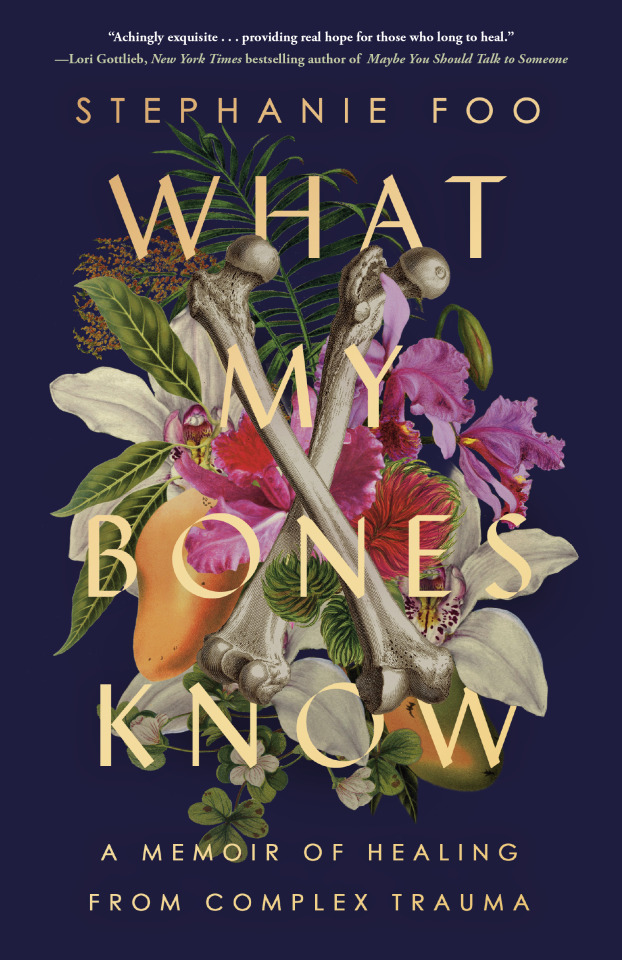

#stephanie foo

Text

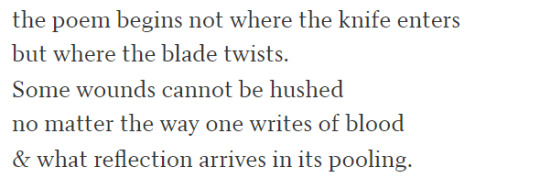

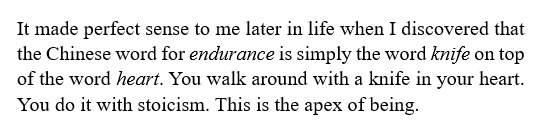

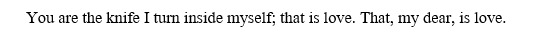

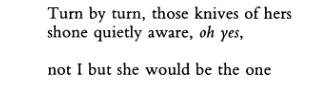

knives & nothing more

hanif abdurraqib prestige \\ stephanie foo what my bones know \\ franz kafka letters to milena \\ heidy steidlmayer knife-sharpener's song \\ richard jackson basic algebra \\ mary oliver march

kofi

#hanif abdurraqib#prestige#stephanie foo#what my bones know#webweave#parallels#web weave#my webweaving#compilations#webs#intertextuality#webweaving#mine#web weaving#on self#on love#web#ww#parallel#parallelism#compilation#intertext#comparative#comparatives#obsessed with everything hanif abdurraqib writes#franz kafka#kafka#letters to milena#basic algebra#richard jackson

506 notes

·

View notes

Text

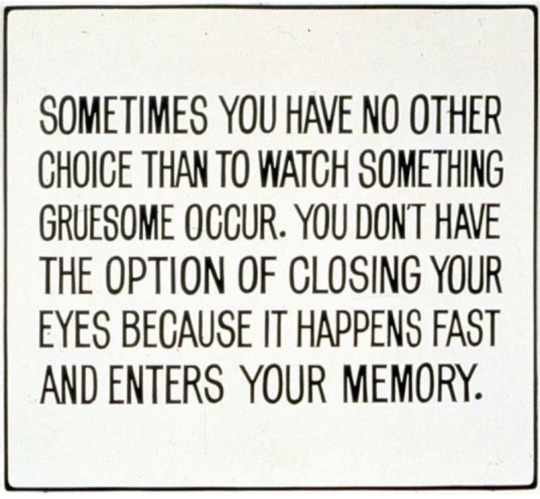

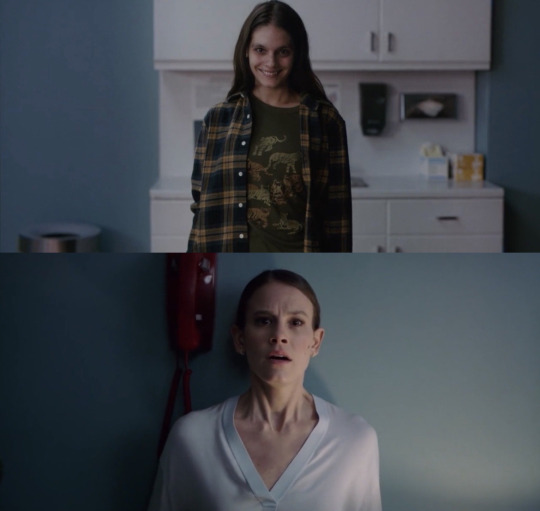

Lake Mungo (2008) / Dark Red - Steve Lacy / Jenny Holzer / Smile (2022) / Blythe Baird / Symptoms (1974) / The Haunting of Hill House (2018) / Sharp Objects (2018) Gillian Flynn / M3GAN (x) / Bells for Her - Tori Amos / Crying During Sex - Ethel Cain / The Poughkeepsie Tapes / Smile (2022) / Black Pear Tree - Kaki King & The Mountain Goats / Whatever Will Be - Tammin Sursok / Ptolemaea - Ethel Cain / When You Finish Saving The World / The Haunting of Hill House (1959), (2018) / What My Bones Know: A Memoir of Healing from Complex Trauma - Stephanie Foo

#parallels#web weaving#comparatives#compilation#lake mungo#steve lacy#jenny holzer#smile 2022#blythe baird#sharp objects#gillian flynn#m3gan#tori amos#ethel cain#the poughkeepsie tapes#kaki king#the haunting of hill house#stephanie foo#horror#trauma

811 notes

·

View notes

Text

[“Sometimes it’s a curse, and sometimes it’s a blessing,” said Greg Siegle, a psychiatrist and neuroscientist at the University of Pittsburgh. He studies the brains of C-PTSD patients, and he told me that my suspicions were right—there were many ways in which C-PTSD could be considered an actual asset. “I call them superpowers,” he told me. “So many of what we call psychopathologies are actually skills and capabilities gone awry.”

Much of my research had stated that people with PTSD had shrunken prefrontal cortices—that experiencing triggers often shut down the logical centers of our brains and left us irrational and incapable of complex thought. But Siegle told me he’d discovered that research to be flawed. He’d found that for many people with complex PTSD, the exact opposite was happening. In moments of intense stress and trauma, our prefrontal cortices were actually far more active.

Normally, if you’re facing a threat, your body immediately reacts to it. Your heart starts pumping blood. The hair on the back of your neck stands up. This is all in service of getting blood to your legs so you can run the hell away from it. On top of this, you feel your heart beating faster. You recognize that you’re freaking out. That makes you even more anxious, and your heart beats even faster.

But Siegle told me, “As far as we can tell with complex PTSD, in really stressful situations, you’ve got this coping skill that allows the prefrontal cortex to just shut off some of our evolutionary freak-out mechanisms and instead have high levels of prefrontal activity. So our bodies stop reacting.”

In other words, in some moments of intense stress, we are super-duper good at dissociation. Our hearts don’t pump as hard. Our brains cut themselves off from our bodies, so we don’t really have that feedback loop of getting anxious about getting anxious. Instead, our prefrontal cortices blink online—we become hyperrational. Super focused. Calm.

Siegle explained it this way: “If running away has never been an option for you, you have to be cunning and do other things. So it’s like, this is time to bring all of our resources online, because we’re going to survive this.”

People with C-PTSD might have an outsized, gnarly freak-out about a cockroach in the house or a flash of anger on someone’s face. But in times of real danger—when someone furious is coming toward us with an actual machete in their hand, ready to kill—we face the problem head-on, while everyone else is cowering. A lot of the time, we’re the ones getting shit done.”]

Stephanie Foo, from What My Bones Know: Healing From Complex Trauma

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Suffering is when you add extra dollops to that pain. You’re feeling bad about feeling bad.

“You’re allowed to have these feelings. Do you know the difference between pain and suffering?” “Um…I don’t know. Do I?” “Pain is about feeling real, appropriate, and valid hurt when something bad happens. Suffering is when you add extra dollops to that pain. You’re feeling bad about feeling bad.” “Double punishment,” I clarify. “Yes. So getting rid of suffering means you’re not adding to the pain. You appropriately felt awkward and uncomfortable and regretful that that dinner party didn’t go well. You appropriately feel annoyed and angry at one of your friends who is being prissy. You’re just accepting of it all. And if the feeling stays, you ask, okay, why is this feeling still in me? And then, assume that there’s incredible wisdom in your intuitions and just start listening to them. What is this? What is this thing in my body right now? What are you trying to teach me?”

— Stephanie Foo, What My Bones Know: A Memoir of Healing from Complex Trauma (Ballantine Books, February 22, 2022)

200 notes

·

View notes

Text

I tried this new idea on for size: “My parents didn’t love me,” I muttered to myself, quietly, then louder: “My parents didn’t love me.” It’s a tragic sentence. It should feel like a shot to the gut. But instead, it had both resonance and stillness. It happened. It’s true. And it’s okay. There are people who love me. I will be cared for. And I have my capable self. Everything is going to be fine.

Stephanie Foo, What My Bones Know: A Memoir of Healing from Complex Trauma

190 notes

·

View notes

Text

I took some notes while listening to Dr. Ham and Stephanie Foo's insta live talk (starts at 45:10). Some tips for people who cannot afford or don't have access to therapy atm (me lol). Dr. Ham also employs parts work, so if you don't know anything about it look up IFS and Robert Schwartz.

The essence of what trauma does:

it makes you afraid of other people, that they are out to get you

it makes you think that you are unloveable

it recreates the pattern of trauma, fear, neglect, abuse in the way you treat yourself

the harsh inner critic is the most classic abusive part

What you can do:

get to know how you treat yourself

understand the functions of all those parts (with love and reception)

you have to basically bring everybody back home

everybody (parts) has been out in the cold playing these very rigid roles (like the inner critic, who is constantly beating you up and saying you're no good, etc...)

you have to relieve the inner critic (who is simply trying to keep you from "getting in trouble" again) from their post

remind them that you survived the trauma (and childhood) and that you now can stomach some disappointment and failure

you have to thank the inner critic for merely trying to protect you and keep you safe

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

“People often ask me what it was like to grow up with this kind of abuse. Therapists, strangers, partners. Editors. You’re telling us the details of what happened to you, they’d write in the margins. But how did it feel? The question always feels absurd to me. How would I know how I felt? It was so many years ago. I was so young. But if I had to guess, I’d say it probably felt fucking bad.”

— What My Bones Know: A Memoir of Healing from Complex Trauma by Stephanie Foo

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

2023 was the year I was able to rediscover my love of reading after a difficult time, particularly at the height of the pandemic. Here are some of my favorite books that I read.

#2023#favorite books#reading#little rabbit#alyssa songsiridej#motherhood#sheila heti#lemon#kwon yeo sun#smoking the bible#chris abani#american woman#susan choi#lady chatterlys lover#dh lawrence#the life changing magic of tidying up#marie kondo#what my bones know#stephanie foo

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

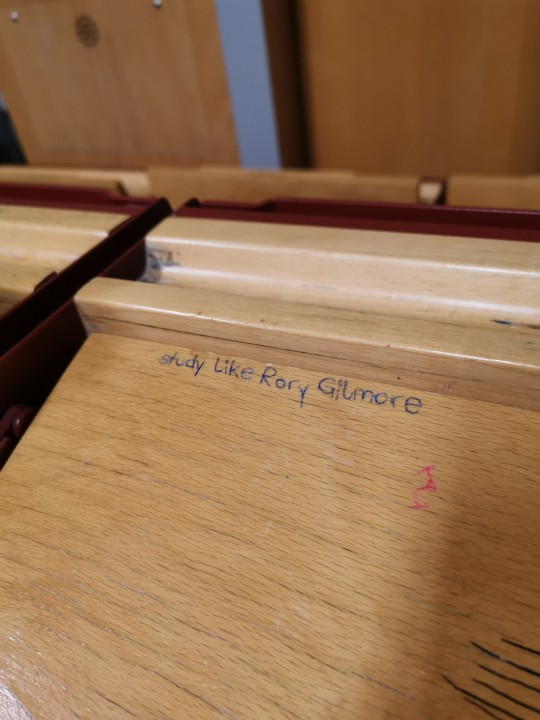

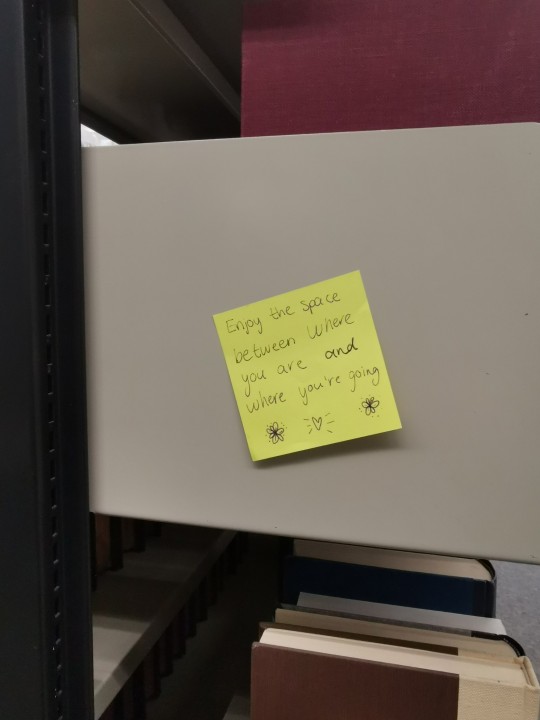

all these little notes hidden around my university and its library

after a little more than a month, I've finally finished What my bones know by Stephanie Foo. I'd say that the book is one of the main reasons why I was in a reading slump in April. The memoir was a heavy read, because of its trauma talk, but also the insights of her therapy sessions or other ways, like mediating or yoga, that Foo attempt to heal herself from CPTSD. I had to put it down and think about what I just read, how I can see some of her behaviours in my own life. This memoir gave me many things to think about for my own life, for my own healing journey. Five stars. No discussion.

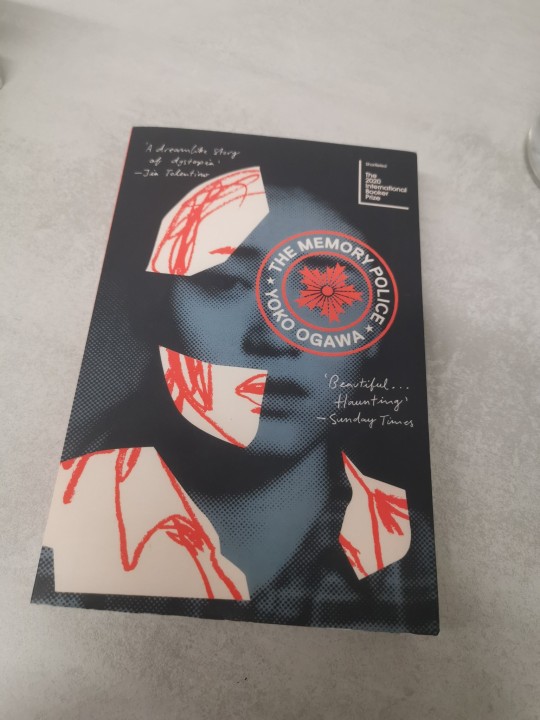

Next read will be The memory police by Yoko Ogawa

#personal#bookblr#books#academia#university#studyblr#library#healing#what my bones know#stephanie foo#book review#book discussion#the memory police#yoko ogawa

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

No matter what I do, no matter where I try to find joy, I instead find my trauma. And it whispers to me : “ You will always be this way. It’s never going to change. I will follow you. I will make you miserable forever. And then I will kill you. “

~Stephanie Foo

144 notes

·

View notes

Text

SARAH MCCAMMON, HOST:

Stephanie Foo grew up in California, the only child of immigrants who abused her for years and then abandoned her as a teenager. As an adult, Foo seemed to thrive. She graduated from college, landed a job at "This American Life," became an award-winning radio producer, was dating a lovely man, but she was also struggling. Years of trauma and violent abuse as a child had left her with a diagnosis - complex PTSD, a little-studied condition that Foo was determined to understand. The result is her new memoir, "What My Bones Know." And Stephanie Foo joins us now from New York City. Hello.

STEPHANIE FOO: Hi. Thank you so much for having me today.

MCCAMMON: I want to start with your diagnosis, because listeners have likely heard of post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD. But how is complex PTSD different?

FOO: Right. So you can get traditional PTSD from a single traumatic event, like, say, you were hit by a car. Complex PTSD is kind of like if you were hit by that car every week for years. It manifested in my life as anxiety, as depression. The difference between PTSD and complex PTSD is that complex PTSD sort of has the potential to have a constant fear sort of churning underneath the surface. And I think it always had me on edge, hypervigilant, made it really hard for me to trust people - and to sort of bury that with intense workaholism, drinking a lot, partying a lot, that kind of thing.

MCCAMMON: Something you come back to a lot in your memoir is the idea of inherited trauma. So I'm wondering if you could talk about your parents' histories a little bit and your family's immigration from Malaysia and how that shaped your childhood.

FOO: I think my parents being recent immigrants gave them fewer resources in some ways. We didn't have access to a lot of family. And my parents, I think, were pretty alone and isolated in their ability to take care of me and in terms of having other people be able to take care of them and the mental illnesses that they suffered from. My parents came from lines of - where their parents had suffered immense traumas. My grandparents and my great-grandparents suffered through World War II. They suffered from the Malayan Emergency. My grandfather was imprisoned by the British during the Malayan Emergency for five years. And when he got out of prison, he lost all of his teeth somehow, and he never talked about it. You know, there were real consequences to that culturally, in terms of the way that they were raised, but even more so in their literal DNA.

MCCAMMON: Yeah, that was one thing that really struck me. I mean, you did some research into how trauma literally can change our genes and how that gets passed down. I mean, what did you learn about how that works?

FOO: Well, there's a couple of really fascinating studies about how our genes can change by what we endure. There's one really famous one where scientists exposed rats to the smell of cherry blossoms and then shocked them. And so these rats came to associate the smell of cherry blossoms with shocks, with fear. And their offspring and then their offspring would have panic responses every time they smelled cherry blossoms, even if they had never been shocked before. So what happens is the epigenome is sort of a layer on top of our DNA that kind of decides what genes get turned off and on. And experiencing trauma can change that epigenome.

MCCAMMON: I want to talk about your therapist, Dr. Ham. He is basically my favorite person in this book.

FOO: (Laughter).

MCCAMMON: How did you find him? And, in short, how did he help you?

FOO: I found him in a very radio producer-y (ph) way. I found him through listening to a podcast (laughter). He was talking about complex PTSD as, like, being the Incredible Hulk, right? Because the Incredible Hulk was actually abused as a kid. His father was an alcoholic, and now he had a hard time controlling his emotions when he was angry. He would sort of literally not be able to speak well, and he would just focus on surviving. And that is exactly what having complex PTSD is like. But the Hulk is not a villain. The Hulk is a hero. And so I needed to know more about that. And so I went to interview him, and he started interviewing me in the middle of me interviewing him. And eventually, he asked me if he could treat me, and I agreed.

MCCAMMON: And you approached this in a very radio producer-y way.

FOO: Yeah.

MCCAMMON: I mean, you have all of your tapes of your sessions with him, right?

FOO: Correct. And after we got done with a session, I would immediately go to the cafe downstairs, and I would upload all of my audio and transcribe it and put it in a Google doc, as you are very familiar with.

MCCAMMON: All too familiar.

FOO: And then we would edit it. And it was like we were editing my trauma out of the scripts. There was a point at which - after our actual first session, I saw, like, a whole page of me ranting about, like, my husband's job, which seemed completely out of left field. And I commented, what is going on here? Where am I? And he said, ah, you are dissociated because you are triggered. And I was like, what triggered me? Why am I dissociated? And I scrolled up. And right before that rant, I had talked about my mom holding a knife to my neck. And I turned off my emotions and my brain to access that, and I needed to disappear in some way to say that. And I got lost on the way. And so that was so helpful for me to just understand, with true journalistic objectivity, I guess, what was happening in my brain.

MCCAMMON: I'm really curious, though. You know, in writing this book and even now in talking about it, you have to go revisit a lot of those traumas again. You're talking about them right now. You're thinking about them. You're writing about them. I mean, how was that? How is that?

FOO: Yeah, dissociation, baby. That's what allows me to be talking to you and saying these things to you right now. And I think the other thing, too, is that I really did prioritize healing before I focused on writing. So writing itself was not the catharsis. Healing was the catharsis. It made me feel like I just wanted to share what I had learned. It was coming from a place of hope, and I wanted to write something that would help other people feel hopeful to. And I don't think that you ever totally heal from complex PTSD. It's sort of something that you carry with you all the time. But I feel like if the burden, the weight of complex PTSD, is like a pack on my back, then the process of healing has made me stronger. Does that mean, of course, that sometimes the pack gets really, really heavy and I need to sit down and take a break and cry a little bit and figure some new stuff out? Of course. Of course. That's what life is. But now I feel like I can hold the sadness and the anger and the joy all together.

MCCAMMON: Stephanie Foo's memoir is "What My Bones Know." Thank you so much for talking with us.

FOO: Thank you so much for having me. I really appreciate this opportunity to shed some light on complex PTSD.

Copyright © 2022 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

[“As adults, Dr. Ham told me, the process of repair is a bit more complex, more transactional. But no less satisfying. “See, for people who are traumatized, all they know is rupture,” Dr. Ham explained. “They always have to come to the abuser with an apology. But it’s never about them having their own needs. It’s not a mutuality thing. It’s a one-way street.”

I thought about this for a moment. “You mean…I was only taught how to apologize whenever there’s a problem and say, ‘I’m sorry. I’m so fucked-up.’ ”

“Exactly. You don’t know how to apologize by making it a two-way repair.”

I stammered out what I thought he was saying. “So for people who are traumatized, that means they’re constantly apologizing…but they’re not having their own issues witnessed and repaired. Or they’re constantly demanding an apology and not—”

“Recognizing the other person. Right!”

“So they’re lacking nuance in their repairs,” I said with some awe.

“Yeah. Forgiveness is this act of love where you say to someone, ‘You’re an imperfect being and I still love you.’ You want to have this energy of ‘We’re not giving up on each other; we’re in this for the long haul. You hurt me. And, yes, I hurt you. And I’m sorry, but you’re still mine.’ ”

“That sounds really good. I want to be able to have that two-way thing. But I don’t know how to do that, really.”

“That’s why you’re here.”]

Stephanie Foo, from What My Bones Know: Healing From Complex Trauma

1K notes

·

View notes

Quote

My fear of being abandoned forced me to need proof of love in abundance, over and over and over again, a hundred times a day.

Stephanie Foo, What My Bones Know: A Memoir of Healing from Complex Trauma (Ballantine Books, February 22, 2022)

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

Trauma is mourning the fact that, as an adult, you have to parent yourself. You have to stand in your kitchen, starving, near tears, next to a burnt chicken, and you can’t call your mom to tell her about it, or listen to her tell you that it’s okay, to ask if you can come over for some of her cooking. Instead, you have to pull up your bootstraps and solve the painful puzzle of your life by yourself. What other choice do you have? Nobody else is going to solve it for you.

Stephanie Foo, What My Bones Know: A Memoir of Healing from Complex Trauma

119 notes

·

View notes

Text

It’s that weird feeling you get sometimes like everything is your fault. (source)

31 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Being healed isn’t about feeling nothing. Being healed is about feeling the appropriate emotions at the appropriate times and still being able to come back to yourself. That’s just life.

What My Bones Know: A Memoir of Healing from Complex Trauma, Stephanie Foo

94 notes

·

View notes