#torah values

Text

Silman: “No One Stood Up To Lieberman On Kashrus, Giyur & Limud Torah”

Silman: “No One Stood Up To Lieberman On Kashrus, Giyur & Limud Torah”

Yamina MK Idit Silman who triggered a political earthquake last month when she resigned from the coalition, spoke to Channel 12 News on Monday in her first televised interview since her resignation.

Silman first expressed her regrets to Yamina voters for her role in forming the coalition. “I gave it a chance but I made a mistake,” Silman said. “I truly thought that after four rounds of elections…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Note

So what’s the modern interpretation of the laws about keeping slaves? I’ve heard that said laws where a lot more kind to slaves then the surrounding nations but, like, it’s still slavery?

Hi anon,

With Pesach coming up, I'm sure that this question is on a lot of people's minds. It's a good question and many rabbanim throughout history have attempted to tackle it. Especially today, with slavery being seen as a moral anathema in most societies (obviously this despite the fact that unfortunately slavery is still a very real human rights crisis all over the world), addressing the parts of the Torah that on the surface seem to condone it becomes a moral imperative.

It's worth noting that the Jewish world overall condemns slavery. In my research for this question, I came across zero modern sources arguing that slavery is totally fine. I'm sure that if you dug deep enough there's some fringe wacko somewhere arguing this, but every group has its batshit fringe.

Here are some sources across the political and religious observance spectrum that explain it better than I could:

Chabad (this article is written by Rabbi Tzvi Freeman, a wonderful rabbi whose words I have learned deeply over the years. He is one of my favorite rabbis despite not seeing eye to eye with a lot of the Chabad movement)

Conservative (to be clear: this is my movement; it's not actually politically conservative in most shuls, just poorly named. We desperately need to bully them into calling themselves Masorti Olami like the rest of the world. It's [essentially] a liberal traditional egalitarian movement.)

Conservative pt. 2 (different rabbi's take)

Reform (note that this is from the Haberman Institute, which was founded by a Reform rabbi. Link is to a YouTube recording of a recent lecture on the topic.)

Chareidi (this rabbi is an official rabbi of the Western Wall in Israel, so in a word, very frum)

Modern Orthodox

I want to highlight this last one, because it is written by the Rosh Yeshiva of Yeshivat Chovevei, which is a progressive Modern Orthodox rabbinical school. They work very hard to read Torah through an authentically Orthodox lens while also maintaining deeply humanist values. As someone who walks a similar (if not identical) balancing act, this particular drash (sermon) spoke very deeply to me, and so I'm reposting it in its entirety**

[Edit: tumblr.hell seems real intent on not letting me do this in my original answer, so I will repost it in the reblogs. Please reblog that version if you're going to. Thanks!]

Something you will probably notice as you work your way through these sources, you'll note that there are substantially more traditional leaning responses. This is because of a major divide in how the different movements view Torah, especially as it pertains to changing ethics over time and modernity. I'm oversimplifying for space, but the differences are as follows:

The liberal movements (Reform, Renewal, Reconstructionist, etc.) view halacha as non-binding and the Torah as a human document that is, nevertheless, a sacred document. I've seen it described as the spiritual diary of our people throughout history. Others view it as divinely inspired, but still essentially and indelibly human.

The Orthodox and other traditional movements view halacha as binding and Torah as the direct word of G-d given to the Jewish people through Moshe Rabbeinu (Moses) on Mt. Sinai. (Or, at a minimum, as a divinely inspired text written and compiled by people that still represents the word of G-d. This latter view is mostly limited to the Conservative and Modern Orthodox movements.)

Because of these differences, the liberal movements are able to address most of these problematic passages by situating them in their proper historical context. It is only the Orthodox and traditional movements that must fully reckon with the texts as they are, and seek to understand how they speak to us in a contemporary context.

As for me? I'm part of a narrow band of traditional egalitarian progressive Jews that really ride that line between viewing halacha as binding and the Torah as divinely given, despite recognizing the human component of its authorship - more a partnership in its creation than either fully human invention or divine fiat. That said, I am personally less interested in who wrote it literally speaking and much more interested in the question of: How can we read Torah using the divinely given process of traditional Torah scholarship while applying deeply humanist values?

Yeshivat Chovevei does a really excellent job of approaching Torah scholarship this way, as does Hadar. Therefore, I'm not surprised that this article captures something I have struggled to articulate: an authentically orthodox argument for change.

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

Integrity: The Silent Force Behind a Life Well-Lived

Hey friends,

I felt compelled today to discuss something that often goes unsaid but is always noticed—integrity.

It's a word we've all heard, but its power is sometimes overlooked, and nowadays is more important than ever.

In its purest form, integrity means doing the right thing when nobody's watching.

It means being the same person in the darkness as you are in the light, acting out of conviction rather than convenience.

But integrity is also about courage.

It's easy to follow the crowd, to go along with what's popular or easy.

But integrity calls us to break from the pack, to stand by our principles even when it's hard. It's a silent force, a moral compass guiding us through life's complexities.

So, the next time you're faced with a difficult choice, remember: integrity may not be the loudest voice in the room, but it's often the most important one.

It's the one that can lay the foundation for a life truly well-lived.

#hebrew#jewish#learnhebrew#hebrewbyinbal#language#israel#hebrew langblr#jew#torah#trending#integrity#values#langblog#hebrew language#language learning#langblr#stand with israel

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

We are all going through so much. All we can do is be kind to each other. And lean on each other for support.

#I am wizard high and having Big Feelinfs about family#and queerness and the way we build our own family’s where we are#and how much that feels like also good Jewish values#and living by the Torah#and feeling like#I made it to adulthood as a proud Jew and I can keep living my best Jewish life#i should sleep#I should also write an essay abt this just bc

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The works of His hands in truth and justice, all His commandments are sure. Juxtaposed forever and ever, made in truth and uprightness."

- Psalms 111:7-8

#jewish#religion#faith#jumblr#judaism#hashem#torah quote#torah verse#torah study#talmud#talmud study#torah#prayer#traditional femininity#tradwife#tradblr#traditional values#psalms

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

Local foreigner that has nothing to do with judaism or Jewish history pretends to be anything more than a person that happens to be of Jewish decent.

Instead of hurting your own people, open a f*cking book.

Tikun olam alek, mefageret.

“Hurting your own people” And the senseless murder of, the brutual occupation and the violence inflicted upon Palestinians whilst IOF soldiers, whilst wearing our symbols, cheer, laugh, mock and boast about the situation doesn’t hurt us? Magen Davids being carved into the flattened grounds of Palestinian homes, sprayed onto walls where families had been slaughtered, and Channukiahs placed in the middle of warzones? The Magen David paraded on a flag as people gather to dance and sing to block humanitarian aid from entering Gaza through the border?

That doesn’t harm us, but the Jews that follow the Torah and know that we are in no place to inflict pain onto another (Exodus 22:20, 23:19) for it is the same pain we have once felt, are the ones causing our people the most harm? Oh because history will hate the Jews that stood up against injustice, certainly not the ones who helped perpetrate it. Give me a fucking break.

Oh and how lovely that you called us an ableist slur! You Zionists are all the same. Self-serving bigots who do not truly care for anything other than their own interests and delusion of grandeur. Your life has no value over anothers, none of us are above anybody, not G-d, not the Earth we walk on. To think you can speak down on Jews who stand against this inhumanity being committed in our name, and even more so, from the sweet haven of anon. Say it with your chest if you stand by this genocide so much. Make sure you let it be known for history that you enabled the genocide of millions.

Anti-Zionist Jews will continue to do the work that honours our ancestors, our people, G-d, and most importantly the people of Palestine. Your vitriol will not stop us from dismantling this.

548 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why is this year different from all other years?

On other years, we dance joyfully with the Torah. But this year, we are brought from Devarim to ein milim.

On other Shabbatot, we lock away our phones and tear the challah with our hands because cutting it with a knife is too violent for the peaceful sanctity of Shabbat. But these Shabbatot, we carry our phones for safety and some even carry weapons.

On other years, Chanukah is primarily about sacred oil and miracles. But this year, it is about war and the cost of Jewish survival.

On other years, Tu b'Shvat celebrates the new year for trees and environmentalism. But this year, we think about crops left unharvested by hands no longer living.

On other years, we celebrate Purim with costumes, candy, drinks, and the purimspiel. But this year, we ask ourselves about the nature of Haman and of self-defense.

On other years, we shout-sing Dayeinu with raucous cheer. But this year, we self-consciously skip the shefokh khamatkha and we wonder if the gentiles know that we spill wine drops from our glass because all human life has value.

This year, we ask ourselves the meaning of "divine" and "liberation."

#המצב#perhaps this will somehow be irrelevant by the time some of these come to pass#in fact b'ezrat Hashem they will be#however

431 notes

·

View notes

Text

To be a ger is to be always a foreigner everywhere you go.

"Ger" literally speaking, meant "foreigner" or "stranger" before it ever meant "convert," and in some texts still means that. Famously the Jewish people is described as being "gerim" in the land of Egypt. Does that mean we were converts in Egypt? No. We were foreigners - strangers whose rights were easily taken away and oppressed, and this is why we are commanded to be kind to foreigners. But there is the rabbinic double meaning of "convert," and the Jewish people is commanded to love converts as well.

But I would argue that there is an element of foreigness to our conversions as well. We are always in some ways immigrants to Am Yisrael. For some of us that may simply have been the experience of it being a paperwork issue, and culturally you have always been at home here.

But for many gerim, we come from outside. We come for any number of reasons, finding our way here through the intuition of our neshama, by chance or by luck, by family or friendship, by allyship, by exposure to Torah or exposure to the Shechinah - or any combination of the above and more.

But we come to the Jewish people asking for shelter and connection. Some of us come with a whole pedigree of Jewish studies and deep prior connections, and some of us come as refugees from other faiths and cultures, with nothing but the spiritual shirt on our backs and dreams of a better future.

And over time, we assimilate. We readily learn the culture and the language and the customs. We learn to cook the food and to follow the laws. We change our clothes to fit with our community and we move to the neighborhood where the other Jews live so we can walk to shul. We reshape ourselves into yiddishkeit and work hard to naturalize.

And eventually we do! We become part of the fabric of the Jewish people forever - having changed our whole lives and changing the shape of the Jewish people in turn. But our roots always lead back to this process. That's not a bad thing or a lack of authenticity - just take a look at the stories of naturalized citizens and you'll see the pride and strength they bring to their new nation. Even so, we are, and always will be, foreign immigrants to this community. Our Hebrew will always have an accent. Our background will lack many of the early milestones that other Jews experience. Our stories and relationships to our families will always be different. You will feel that sometimes. That's okay! That's normal, even years later.

What caught me a bit off-guard, though, is how much part of being a Jew in the diaspora is to always, in some way, be a foreigner also. It seems obvious enough, right? But I had never fully connected that feeling of foreigness from my conversion in to the perpetual foreigness of Jewishness that takes root from our conversion out.

Because once you leave, once you change your culture, you become an outsider and a foreigner to the dominant non-Jewish culture around you. You sound different. You dress different. People perceive you differently and you in turn react differently. You have changed your culture, and in so doing, become a cultural outsider.

There's a bit of ennui to it sometimes, I've found, of always being on the periphery. We are joining, have joined, a liminal people and yet are liminal people even within that people. This is nothing to do with active exclusion — many of us are lucky enough to have found ourselves ensconced in wonderfully welcoming communities that treat us as valued members of the tribe. Rather, it's much more just a practical reality of being a person who left behind one culture and assimilated into another. You can never fully sever your roots any more than you can rewrite the past, but you have also changed so deeply that to return would not be any more possible than returning to a past iteration of yourself. That person is gone, and you are new, and you have become something different, and you are from There and have come Here, and in so doing, a part of you will always be a ger, a traveler, a foreigner, a stranger, and the only thing you can do is embrace it.

What we mean by "home" is always so interesting, isn't it?

197 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m a Torah-loving Jew who is also a radical leftist. I study midrash and I study theories of change. I use Mussar to strengthen my anti-racist muscle. I seek out Jewish metaphors for anti-oppression work.

Zionists believe they deserve my loyalty because I love Torah. Anti-Zionists believe they deserve my loyalty because I’m a radical leftist. They’re both right. I’m loyal to both, because they’re my people. Jews are my people and justice-pursuers are my people. But I’m realizing for many, I’m not theirs.

The Zionist/anti-Zionist binary is fucked up and insufficient (like all binaries), and it is hurting people (like all binaries). Both sides are allowing disinformation and partial truths to corrupt their values and their humanity, and the end result is perversion and suffering and danger. I’m sick and heartbroken and deeply lonely.

#jewish#jumblr#antisemitism was there all along but I thought it was harmless#I was wrong#I miss community#it doesn’t feel safe right now#I might regret this#not interested in arguing about this#just needed to say it somewhere

260 notes

·

View notes

Text

I don't think people understand how intrinsically Jewish the Les Misérables musical is. The writers of the original French musical were Claude-Michel Schönberg (Hungarian Jew), Alain Boublil (Sephardic Jew), and directed by Robert Hossein (Moldovian Jew). Schöneberg also composed the music. It was adapted into English by Herbert Kretzmer (Lithuanian Jew).

The lyrics include many references to Jewish beliefs and values. Schöneberg said in an interview, "When I’m writing a show there is always a part that is typically Jewish."

However, the one that sticks out to me especially is a line from the Epilogue:

"They will live again in freedom,

In the garden of the Lord;

They will walk behind the ploughshare,

They will put away the sword."

The origin of the phrase - specifically, the bit about 'ploughshares' and 'swords' - can be traced back to a nevuah (prophecy) by Yeshayahu (Isaiah), a Jewish navi (prophet) from the sefer Yeshayahu (Book of Isaiah). (Sorry, yes, I insist on the Hebrew words first.)

"The Torah will go forth from Tzion (Zion) and the word of Hashem from Yerushalayim (Jerusalem)... They will then cut their swords into ploughshares, and their spears into pruning knives. No nation will lift a sword against the other, and they will no longer learn warfare."

This is a quote about the 'end of days', and the idea of a peaceful paradise free from war was emulated in the song to convey a similar paradise for our barricade boys, the casualties of the June Rebellion. This is only one of the many examples of Jewish themes and references in the Les Misérables musical!

#les mis#les miserables#judaism#isaiah#yeshayahu#navi#claude michel schöneberg#les mis musical#les miserables musical#alain boublil#herbert kretzmer#robert hossein

346 notes

·

View notes

Text

WHAT DO ALL OF THESE BOOKS HAVE IN COMMON?

ANSWER UNDER THE CUT

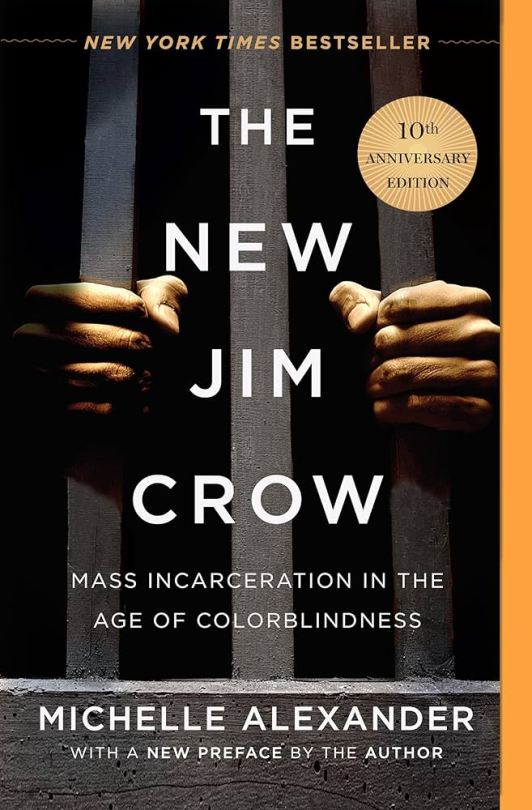

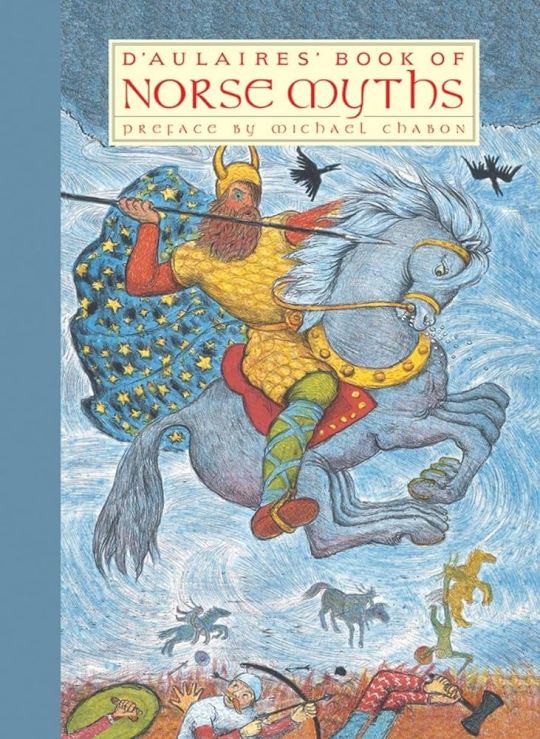

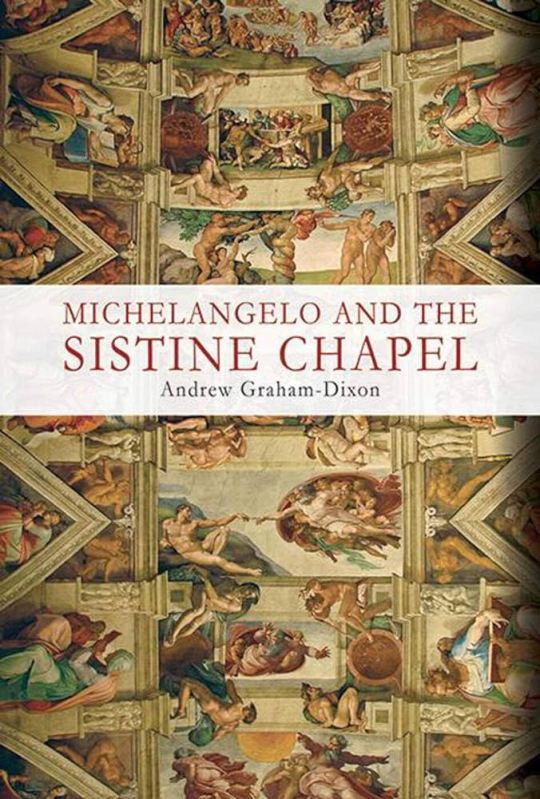

All of them have been banned, or access to them has been restricted, in a prison in America within the last ten years.

In many states, prisons have broad and vague guidelines for book restrictions -- N.J. Admin. Code § 10A:18-4.9 grants prisons the right to ban a book if it "Lacks, as a whole, serious literary, artistic, political or scientific value". In Arizona, "inmates are not permitted to send, receive, or present... Publications that depict nudity," and explicitly states that classical art is not an exception (DO 914: 8.2.1 and 8.2.1.1).

I volunteer at a nonprofit that sends free books to prisoners. From personal experience, I know there are sweeping book restrictions such as "no dictionaries," "no coloring books," or "no manga". While these books are not always strictly banned, inmates are frequently underpaid, or forced to labor without pay. That means many inmates cannot afford to purchase books, and rely on nonprofits for access.

Book bans in public libraries and schools are unconscionable, but they are usually not effective at restricting access. A high school student can usually still see an image of Michelangelo's David even if they cannot learn about it in class. In prison, a book ban on nudity can permanently prevent inmates from accessing great works of art, the shared heritage of humankind.

DONATE TO THE INSIDE BOOKS PROGRAM IF YOU HAVE THE OPPORTUNITY. THEY SEND FREE BOOKS TO PEOPLE IN PRISONS.

Sources:

Found on Marshall Project

1,001 Movies You Must See Before You Die (banned in California according to Marshall Project

Basic Fundamentals of Modern Tattoo (Illinois)

No role playing games. A Practical Guide to Dragons. Abolish Prison Slavery. “A Multi Denominational Wicca Bible. (Montana)

101 Things to Do With Mac and Cheese (New Jersey)

“But, Didn’t You Kill Malcolm?” and “A Field Guide to Lucid Dreaming” (North Carolina)

“100 Years of Chevrolet” “1000 Dot to Dot Animals” (Oregon)

“San Francisco Bay Newspaper” “Making Everyday Electronics Work” (Rhode Island)

“Marvel Encyclopedia” (South Carolina)

“A Brief History of Manga” (Texas)

“1001 Photographs You Must See in Your Lifetime” (Virginia)

“A Question of Freedom” Reginald Dwayne Betts (Wisconsin)

The Tennessean

A prison in Tennessee restricts access to The Quran, The Torah, The Bhagavad Gita, and books about Norse mythology. (The ban did not apply to the Bible.)

Personal Experience

I am not willing to dox myself, so I cannot name the nonprofit where I volunteer. However, I swear that I have seen book bans on manga, how-to-draw guides, coloring books, electronics books, dictionaries, and composition notebooks.

128 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm very frustrated with how the various youtubers and streamers talk about Ben Shapiro.

Because they do not understand or have the proper context when talking about him and everything he represents.

They also often go into antisemitic territory when mocking him, while it is unintentional and something they may not not even know they are doing, they are doing it none the less.

When they mock his voice or call him Shabibo that is actually antisemitic territory.

Due to a history of Jewish people having our names stripped from us and voices and names mocked. Now I too find his voice to be personally annoying, but I won't mock it because of said history.

It is not about the curtsy that Ben Shapiro deserves or doesn't deserve, but rather about deciding when it is okay to employ antisemitism against a Jewish person.

The answer is never.

The overwhelming majority of these commentators are not Jewish and the few that are Jewish don't seem to know any of the important details that make what Ben Shapiro says so dangerous for all Jews and such a false representation.

See what is not presented in discussions about him is that Ben Shapiro is not there to pull in a Jewish audience he is there as a token Jew to help further pull in an christian audience.

That is what makes it all so very insidious in nature. And sadly some Jewish people get fooled by this too because they do not look beyond the front facing facade he wears like costume, but they do not actually listen the words he says.

Ben Shapiro harps about a 'war on christmas' which no Jewish person would seriously do or care for. Especially any Ashkenazi Jews with our very long long history of being murdered in mass on xmas. Christmas eve is became seen a spiritually impure night that it would be called Nittle Nacht in Yiddish and Jewish people would purposefully not study Torah that night.

American Jews, like many others who belong to non-christian religious and cultural groups, have to deal with living a majority Christian country and country that culturally Christian and only makes concession for Christianity.

Has Ben Shapiro ever talked about that or the actual fights to get time off for our Holidays? No because that doesn't fit the narrative. But business having employees switch from 'merry christmas' to 'happy holidays' most certainly does.

Ben Shapiro has explicitly stated that he believes that conception is when life begins which is something to no in keeping with any Jewish held belief anywhere.

We hold life begins at first breath, the mother comes first (I wrote mother because that is wording used in the various writings, but really it would be the pregnant individual comes first), and that it doesn't just need to physical health on the line it can also be one's mental health at stake in order to need an abortion

Ben Shapiro talks about Judeo-Christan values, which a bullshit term that was created after the Holocaust to make it seem like Christian Antisemitism played no role in what happened and that the Church was not a guilty party. It is also a term that essentially holds Jewish people hostage.

He uses this term and talks about these shared values. So I have to ask what values?

Is respecting the elderly, caring for the sick, kindness to others, tending to the poor, and such? Because those are universal values and can be found in pretty much every culture and religion.

What about original sin? Heaven and Hell? Can someone be the literal child of G-d? Does G-d have literal hands, a actual face? What is the gender of G-d?

Just some questions to start with since you know we clearly have the same values and stuff.

Because Judaism would say: No such thing as original sin and in fact Hebrew doesn't have a word for sin we have words that mean things that wrongly translated in English as sin, but no, word for sin. We hold all people are born blank we go through and have experiences and make choices and those choices speak to who we are.

We believe in This World and The World to Come and the spiritual washing machine so to speak, but no a big nope to heaven and hell. No to Satan too. There is the HaSatan which means prosecutor who is as the name means in the Ultimate Court.

When we say "we are the children of G-d" it is poetic flourish and is metaphorical not literal no one can be the literal hild of G-d.

Same way we anthropomorphize G-d so that we have an easier time contextualizing G-d because otherwise it can be hard to wrap your mind around.

G-d is both genderfull and genderless at the same time. It depends on what you are talking about, in what context, and what aspect of G-d of you using. For example the Voice G-d and Presence of G-d are both in the feminine in Hebrew.

These have just been a tiny amount of examples from a vast vast array them.

My point is that if all these people are going to talk about Ben Shapiro especially ones with large followings please bring on someone who is actually knowledge and qualified to talk about this so the facts can properly be presented and explained.

Like I on occasion will listen to Leftovers podcast in background it hosted by Ethan from H3H and Hassan Piker and in the most recent episode that I was listening, which I had to stop because I was getting to annoyed by, they where talking about Ben Shapiro.

It was very frustrating for me. I get that Hassan might be very politically involved and knowledge about stuff, don't really know I don't watch him, but I was thinking the whole time that this is not an area you know.

You are talking about Jewish stuff and things related Jewish views points and you have no clue what you are talking about. You are talking about a religion and culture you just don't know anything about and are trying to debunk Ben Shapiro.

It will not work because you don't have necessary information and understanding to do so.

And you are missing the biggest point of it all which is again Ben is there as a draw for Christians. Because for these kinds of Christians having a Jew give a stamp of approval gives it some kind veneer of legitimacy.

It validates them and allows them to not have to feel guilty for crimes against Jewish people that they are party too.

This doesn't mean they like Jews or want us around or interested in our problems or helping us.

It is all about them in the same way they have Candace Owens tell them all the thing they want to hear so they never have to self-examine or reflect on anything and can assuage their white-guilt and keep of being horrific anti-Black.

They don't care about Black people or Black issues because they listen to a Black woman talk.

It is all for self-serving interests that they have been Ben and Candace there. While many seem to get that point (if you didn't get it before well get it now) in regards to Candace Owens and the purpose of her employment they miss that very important detail when comes to Ben Shapiro.

#ben shapiro#antisemitism#jumblr#christian antisemitism#evangelical antisemitism#protestant antisemitism#an essay of a post

336 notes

·

View notes

Text

Milton Erickson and a Rabbi Walk into a Bar... (Essay)

Finally, I've finished this essay about connections I'm finding between hypnosis, Judaism, magic, and intimacy. It's ~4.5k words, extremely "me," and I'm really thrilled to share it. Enjoy!

--

My weakness is getting deeply invested in very niche topics.

Hypnosis was my first and most lifelong obsession. It was my confusing, shameful sexual fetish that I eventually took by the horns and -- through my desire to learn as much about it as humanly possible -- turned into a job. But not a normal sex work job where I do hypnosis for money -- a weird job where I just teach about it. The kink community, and the further-specific niche where people want to hypnotize each other during intimate experiences, became my home.

But the value of study doesn't really come from the quantity of people I'm able to engage with. It comes from the way it enriches my life. It creates and benefits from the capability to see overlaps between all of my various interests.

On the surface, it may appear that two skills have no relationship. But the deeper you get into each one, a synthesis appears.

At a certain point when you are learning hypnosis, all seemingly-unrelated information seems to fit effortlessly into your hypnotic knowledge. You can listen to a song and suddenly you learn something new about how to hypnotize someone. Maybe it was a lyric that gave you an evocative emotional response; maybe it was a pattern in the music that you thought about replicating with the rhythm of your hypnotic language.

Over a decade into my own hypnosis learning, I got very lucky and found a second passionate home in communities of Jewish text study about a year ago. I started from almost zero there and found myself again to be a greedy novice, obsessed with digging into it.

Of course, as I got further, it became that I read a page of Talmud (a text of rabbinical law and conversation) and suddenly I learned something new about how to hypnotize someone. And as I progress, it is starting to go the other way: I learn about Torah study by reading about hypnosis and intimacy.

There are two directions this essay can be read. “How can intimacy and hypnosis teach us about Jewish text?” And, “How can Jewish text teach us about intimacy and hypnosis?” One half is of each part written by me as an authority, and the other half is by me as an avid novice. The synthesis of these two parts of me -- just like any synthesis between concepts -- may perhaps create something new.

Models

I’m sure most communities have a version of the idiom, “Ask three people a question and get five answers.” For a long time, this was a source of frustration for me in the hypnosis community. Is hypnosis a state of relaxation and suggestibility? Kind of, but also no. Is it more accurate to say it is based on unconscious behaviors and thoughts? Well -- kind of, but also no.

So what is it? Well, it’s probably somewhere in the overlap of about 20-30 semi-accurate definitions and frameworks for techniques -- what we’d call “models.” Good luck!

Why is hypnosis so impossible to define and teach? How have we not found a model that we can all agree upon yet? I think many people share this confusion, and it's complicated by the fact that most sources for hypnosis education teach their model as the model. It makes sense -- it would be difficult to teach a complete beginner a handful of complex frameworks with which to understand hypnosis when that person is just trying to muddle through learning “how to hypnotize someone” on a practical, basic level.

…Or would it be? By the time I got involved with Jewish study, I had long given up on chasing the white whale of some unified theory of hypnosis. I was firmly happy with the concept that all ways to describe hypnosis are simply models -- and all models are flawed, while some models are useful. I was delighted, when entering Jewish community spaces, to hear the idiom, “Three Jews, five opinions.”

This concept is baked into Jewish text study, in my experience. You can look at any single line in Torah and find innumerable pieces of commentary on it, ancient and modern, with conflicting interpretations. Torah and other texts are studied over and over -- often on a schedule -- with the idea that there is always something new to learn. And this happens partially by the synthesis of multiple people's perspectives adding to and challenging each other, developing new models. My Torah study group teacher always starts us with a famous line from Pirkei Avot, a text of ethical teachings from early rabbis: “If two sit together and share words of Torah, the Shekhinah [feminine presence of God] abides among them.”

The capacity to develop and hold multiple interpretations at once enriches your relationship with the text. So too do I believe that being able to hold multiple interpretations of what hypnosis is and how it works enhances your skill with it. It is not a failure of the system -- it is the best thing about it.

Intimacy

It is intentional to make the distinction of “relationship with the text” -- not “relationship to the text.”

My job on the surface is to teach hypnosis, but the meta goal is to simply teach something that helps people develop profound intimacy with others. I think that hypnosis is a kind of beautiful magic that is well-suited to this, but it’s not the only path to take.

One of my favorite educators, Georg Barkas, describes themselves as an intimacy educator who teaches rope bondage. Their classes and writings are highly philosophical and align closely with my own ideas about intimacy -- as well as my partner’s, MrDream, from whom I’ve learned so much. I frequently cite Barkas when I talk about hypnosis because I feel the underlying ideas they have about rope bondage are extremely applicable to all kink and intimacy -- and I will continue that trend here.

Barkas recently published an excellent essay looking in detail at the concept of intimacy itself. They posit that our first thought of intimacy is usually about a kind of comfort-seeking and familiarity. That’s contained within the etymology of the word, and socially it’s what many of us think of when we define our relationships as “intimate”: settling in to engage with a partner who we love, know, and understand.

But, Barkas asks, what if we place this word into a different context? They talk of how in scientific endeavors, the goal of “becoming familiar with” is unpredictability and discovering things that are surprising and unexpected. This perhaps offers a different view of intimacy: intimacy where you do not engage with your partner as though you know everything about them; intimacy where being surprised by them and learning something new is the goal.

My partner MrDream teaches about this often in hypnosis education: approaching a partner with genuine curiosity and interest -- “curiosity” implying that you don’t know what to expect, with a positive connotation. There is a kind of delicate balance between being able to anticipate some aspects of what is going to happen hypnotically -- to have a general grasp on psychology and hypnosis theory -- versus holding tight to a philosophy that neither you nor the hypnotic subject really knows how they are going to respond. The unexpected is not to be feared, but celebrated and held as core to our practice. Hypnotic “subjects” (those being hypnotized) who can relax their expectations will often have more intense experiences.

Thus we come to the first time in this essay where I mention Milton Erickson, my favorite forefather of modern hypnosis. Erickson was a hypnotherapist active through the 1900s and is famous (among many things) for presenting a model of hypnosis that wasn’t necessarily an authoritative action done to a person, but a collaborative and guiding action done with a person.

In his book “Hypnotic Realities,” he talks about how his view of clinical hypnosis is defined by how the therapist is able to observe each individual client and directly use those observations to continually develop a unique hypnotic approach with them. The client’s history, interests, and modes of thinking are utilized for the trance, as well as any observable responses they have in the moment. For example, a client with chronic pain may have the frustration they express over that pain incorporated into the trance. This is in deep contrast to hypnosis where the therapist comes in with any kind of “script” or formula to recite ahead of time.

It’s important to Erickson’s model that the therapist doesn’t know exactly what to anticipate, and it’s also important hypnotically that the same is true for the client. A common “Ericksonian” suggestion is, “You don’t have to know what is going to happen, and I don’t know either.” In order to develop the most effective approach with each patient, Erickson would enter into a session with some presumed knowledge, but ultimately learning -- not assuming -- how to best hypnotize each individual person.

We circle back to the phrase, “a relationship with Jewish text.” In my opinion, engaging with Torah is exactly this kind of intimacy. Torah is something we come into in order to poke and prod at it, to interact with it and to see how it interacts back at us. The teacher of my study group always cites a model where Torah itself is a participant in our partnered learning and group discussions. We ask it questions, we push its boundaries, we strive to glean something new and yet unseen. A line that may seem simple on the surface can reveal much more when we explore its context or put it into a different context entirely.

This is easier for me to say as someone who is coming into learning Torah for the first time, but I am able to look ahead to when I will be fully familiar with the text and still be able to take this expanded definition of intimacy with it. Not coming to it without a sense of comfort, but still engaging with curiosity. MrDream teaches a model for hypnosis that is based on the idea of exploration -- exploring your partner no matter how long you have been with them. You are always coming to them as a different person, shaped by your ever-growing experiences and identity, and your partner changes as a human as well. I believe Torah is also dynamic in this way, as the context within which it exists -- and the way we interpret it -- is constantly shifting.

Ritual

I have been engaging with spiritual ritual on and off for as long as I’ve been learning hypnosis. The concept of magic has always been alluring to me -- not from a motivation to meet specific goals, but for something more difficult to pin down. I like that ritual, in an esoteric framework, is about looking at various metaphors between ingredients and actions; a candle representing an element of fire which may in turn represent intensity, or purity, or something else. Drawing meaningful connections between concepts like this is a skill I’ve developed in parallel with hypnosis, as well.

I was recently talking with a friend of mine who is also interested in esotericism -- we were sharing our frustrations with various books on magic and ritual. We wondered why so many sources would go on to teach prescriptivist formulas and associations, and not much else. Do this, and that will happen. This symbol represents that. My friend and I agreed that the ritual value of ingredients comes from how you personally assign meaning to them -- but why was everything always trying to teach us their meaning, as opposed to teaching us how to cultivate our own associations?

A week or so later, I happened to go to an excellent class that explored whether or not there was a place for smudging and smoke use in modern Jewish ritual. The teacher first took a careful, measured approach towards looking at indigenous smudging practices and the concept of appropriation. What followed was 30 minutes of history and text exploring examples of smoke in early Judaism, and then 30 minutes of a handful of interpretations of what “smoke” could mean and represent with relation to Jewish ideas -- directly practical to modern ritual. It was utterly excellent and immediately profound for me, as someone who has been yearning to blend my experience with esoteric ritual with my relationship with Judaism.

Observant readers will note that through this essay I speak passively about Judaism -- I am a patrilineal Jew, which for better or worse means that it is not a simple matter to say, “I am ‘fully’ (or ‘not’) Jewish.” (I am in the beginnings of working with a Conservative rabbi -- who affirms that I’m Jewish -- to make my status halachic [lawful], which is deeply exciting.) Opinions on that aside, a relevant piece of information is that the Jewish holiday we celebrated most consistently when I was growing up was Chanukah. While a lot of Jewish practice has been something I’ve been striving towards as an adult, Chanukah has always been “mine.” It was fast approaching after this class, and I felt motivated to use my newfound knowledge to make more ritual out of lighting the candles.

I was deeply surprised when all I did was light a stick of incense before saying the blessings over lighting the menorah, and my experience transformed into something intense. I smelled the incense and couldn’t help but think about what I’d learned about the Rambam’s commentary that incense in the time of the Temple was about making the Temple smell sweet to pray in after the burning of sacrifices. I thought about what I’d learned about the presence of God being smoke and clouds to the ancient Israelites. I thought about things I’d learned from other places -- hiddur mitzvah (the value of beautifying a practice), and a midrash (parable) about God loving the light and rituals we do in a very personal way simply because they are from us.

Esoteric ritual has often felt to me like exerting effort in making the associations of ingredients work for me. But this was effortless. I was doing something that was entirely my own, solidly founded by the broad and deep study I’d done, by my personal relationship with the concepts, by my identity.

In other words, the power behind this ritual came from knowledge, and the knowledge came from my intimacy with it. And that intimacy was not just with the study I had done -- it was also the process of being surprised in real time by what I was learning through the ritual itself.

Hypnosis gains “power,” in so much as we let ourselves use the term, through these same acts of intimacy towards knowledge. It operates directly based on various ingredients: how much we know about hypnosis theory itself, general psychology, the person we are working with, and ourselves. Hypnosis is a ritual -- it is setting aside special time to do something with a collection of ingredients that you have personal associated meanings with. If you can’t connect to those deeply enough, it won’t reach its full potency.

Knowledge, Perception, and Unconsciousness

One of my favorite concepts to teach in hypnosis is, “A change in perception equates to a change in reality.” This is derived from Erickson by MrDream, and it’s something he and I have had a lot of conversations about to refine. The implication of this is not something as trite as hypnosis having the power to change a person’s perceived reality. It is the concept that if you look at something from a different perspective, you gain various different capabilities.

For example, when you are feeling stuck in a situation and you think about what a close friend of yours would do if they were in your shoes, you gain the capability to see more options, to change your actual view of the reality of the problem and therefore change your actions towards it. In hypnosis, this could be the difference between simply telling someone to relax their legs versus another perspective of telling them to imagine what it would be like if their legs just started relaxing. It could be the idea that when a person does feel relaxation from a simple suggestion, their perception changes on what is happening -- they build more belief in hypnosis, and that belief in turn makes the next suggestions easier to buy into.

Erickson’s model of hypnosis is predicated on the idea that hypnosis itself matters, that hypnosis is a time within which someone’s reality changes. In his ideal hypnotic context, the subject feels like they no longer can expect things to behave as they usually do in their “waking” reality. They are thus opened to many different kinds of new experiences and capabilities. To Erickson, perception matters -- by itself, it’s a primary driving force behind literal change and response.

This ties back to our idea of intimacy -- just as I aim to approach my partners with this profound curiosity, just as I aim to approach Torah, I want to have this intimacy of the unexpected with trance itself. I want to allow myself to be surprised by hypnosis, by the things I don’t yet know about it even after more than a decade and thousands of hours of trance. But more than this, in an Ericksonian sense, simply changing my perspective to this motivation is one of the things that lets me get there.

I went through a guided study class about Shabbat (Judaism’s weekly sabbath of rest) with a partner, and so much of the class was in the abstract that it at times felt difficult for me to latch onto. We were learning all of this background context about a view of Shabbat where instead of spiritually striving and reaching on that day, you come in acting as though your spiritual work -- like your other work -- is “finished.”

In one session, we spent a chunk of time parsing through how we could interpret that as actionable. It felt like it just wasn’t clicking for me -- the midrashic texts weren’t offering enough for me to feel like I could make judgments on questions like, “Does this imply I shouldn’t meditate on Shabbat in this context?”

It wasn’t until I slept on it that I found a very simple piece of the puzzle: putting aside the questions of concrete actions, in an Ericksonian sense, the internal act of shifting my perspective would absolutely change the way I behaved and interacted with the day. It would become more indirect and unconscious -- instead of carefully analyzing my actions as I might with other Shabbat prohibitions on work, I could simply let myself act in ways that fit that perspective of “spiritually resting.”

The abstraction of the class made more sense -- perhaps it wasn’t trying to give us direct answers, but rather create a psychological environment for us that was well-suited to this more unconscious processing. Or rather, in addition to the sort of typical conscious halachic interpretation. If I allow myself an opinion here, I’d say that I care about halacha as actionable, but as always, I tend to care more about feelings and what’s internal.

This also lent credence to ways this class and the class on smoke and ritual changed my experiences. I was not given a set of actions to take, but rather a variety of perspectives that unconsciously made me think and behave differently. The concept of “knowledge is power” is both true and alluring in many different contexts, and yet had often fallen through for me in most ritualistic frameworks. The way that it succeeds, I believe, is when you develop a relationship with knowledge that actually changes your internal perspective and perceptions.

Limitation

With this we return to the concept of models and interpretations. It is serendipitous to be going through these experiences at a time where I am avidly working on my next book -- the thesis of which is that in order for us to progress as hypnotists, we must get comfortable moving fluidly between many differing definitions and frameworks (models) of what hypnosis is and how it works.

It is as the Ericksonian principle would say: If you take a perspective on hypnosis that boils down to “hypnosis is about relaxing the conscious mind,” you will do hypnosis according to that perspective. You will use relaxation-based techniques and make an effort to get someone to think “less consciously.” If you instead take a perspective that is “hypnosis operates based on activation of the conscious mind,” you may do hypnosis that causes someone to think and process in a more stimulating way.

Both and neither are true, and they can coexist. I believe that most models can be useful -- some more useful than others. But the best thing you can do is to not assume that one model is the most correct one -- instead, it is to develop the capacity to work within many at once even while being aware of their boundaries.

Jewish text, in my experience, provides models -- perspectives that themselves give guidance on how to understand things and act. I think especially about midrash and stories that are explicitly intended to fill in the gaps or give an alternate view on something. The question of, “Is there one correct way to do/see things” is more complicated here, but there are areas -- especially in those subtle shifts of mindset for ritual or interpreting text -- where the answer is still “no.”

My time so far in Jewish study supports this in a different way. There is a human element of collaboration and challenge. Learning as we do with a chevruta (study partner) adds another person to the relationship -- it is no longer just between you and the text. There is another human who you are building something with, and it is “intimate” according to our exploratory definition in an even clearer way.

The purpose of a “scene” inside of kink (a “session” of kink play) is to operate in a semi-limited framework -- limitations exist on who is involved, where it begins and ends, how partners communicate, and what themes/topics/activities are involved. These limitations -- though they may be quite broad -- are partially what allow for intense experiences. A scene needs to exist in a different “space” than our daily lives, and it needs to operate by different rules and involve different ingredients. Here, we also see overlaps with the definition of a “ritual.”

This doesn’t just facilitate intensity (and safety) -- it facilitates learning something new about your partner. By taking your relationship and putting it into a limited context, it allows you to observe it in a more careful way, where novel changes can be more obvious.

Studying with a chevruta is much like this. I have had study sessions where my chevruta and I are meeting for the first time and the only thing we are aware of sharing is our desire to dive into a piece of text. I’ve also had chevrutas where we know each other outside of study, and some of our time is schmoozing and catching up. But in all cases, we are limited in scope, and that limitation creates ease of access towards the common goal of expanding our knowledge and relationship with the text. We are focused; we are motivated. We are creating something that we can only create through who we are as individuals and what we are doing as avid learners.

This has surprised me at times with its tenderness and intensity. Building well-founded interpretations with someone is in and of itself very intimate -- not sensually, but humanly. It has given me something I have always wanted -- an intimacy that is pervasive not just in application of knowledge, but in the development of it. A feeling of sacredness and joy from being able to see so many different perspectives.

I long for this connection, this alchemy. Yes, all models are limited. But within those tight, restricting limits is the potential energy of creation.

“And I Must Learn”

There is an infamous story in the Talmud, in Berakhot 62a, where Rav Kahana hides under the bed of his friend Rav Abba. Rav Kahana hears Abba and his wife giggling and starting to have sex, and remarks out loud that Rav Abba is acting like someone who is famished. Rav Abba, mid-sex, understandably says, “Kahana, why the fuck are you under my bed listening to me fuck my wife?” Rav Kahana replies, “It is Torah, and I must learn.”

There was a version of this essay that began with this tale. I am enamored with the vast overlaps I can derive from its briefness: that intimacy can be studied sacredly both as a general concept and specifically with your partner; that we are obligated to learn ourselves, our partners, and general human desire; that there can be a thread of wholeness in every action of your life if you give every action sacred attention.

Even this, though, is a limited-context interpretation. The rabbis of the Talmud were certainly not sex-positive, especially not as we currently use the term. The surrounding triptych of conversations is similarly humorous but seems to comparatively describe sex as dirty or gross, and this bit of text cannot really exist separately from all of the places where there is halacha derived about sex that is about controlling women’s bodies or preventing queer and trans people from being able to live authentically.

But -- we are allowed to interpret like this. We are allowed to play with context and see what we discover.

For me, this is about finding the connections between my actions and my interests; parts of me that synthesize the whole. It is about developing intimacy with Torah, with my learning partners, with my romantic partners; with the people within the writings, with the authors, and with the readers.

Reading Torah is the same as hypnotizing someone is the same being intimate with someone is the same as doing a ritual. All things on a broad enough scale overlap this closely. There is value in this “zooming out” to a wide enough context to see the connections that exist -- just as there is value in celebrating the limitations that arise, models nestled alongside each other, when you “zoom in.”

We need both to be able to treat our learning -- all forms of it -- as something special.

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

Decency and fairness are the bedrock of moral society.

Decency carries the torch of respect and empathy, illuminating the path to human dignity.

It's not just about actions; it's a state of heart—a commitment to elevate interactions with kindness and respect.

Fairness is the scale that balances this ethical equation, ensuring that each person is weighed by the same measure, their worth defined not by status but by their humanity.

In a world brimming with diversity, decency and fairness are the universal languages that connect us, fostering trust and understanding across the tapestry of human experience.

Together, they are not just ideals, but practical necessities for a society that values each of its members and strives for justice and harmony.

#hebrew#jewish#learnhebrew#hebrewbyinbal#language#israel#hebrew langblr#jew#torah#trending#decency#fairness#values#virtues#hebrew language#language learning#online learning#learn#learning#langblr#langblog#languages#jew tag#j tag#stand with israel

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Radical Inclusion has lived within Jewish texts from the most ancient of our beloved stories, and has been a value that we've been learning from for centuries. Come join the conversation of the ages, inspired by our texts to make our Jewish Family a safer, more inclusive, kinder, and more loving for every last member of our community.

This text study will explore wisdom from the Torah, Medieval Commentators, and Contemporary Jewish leaders and clergy. This text study is partially inspired by Rabbi Gischner's senior sermon on the topic of inclusion vis-a-vis the priestly garments, as well as other stories from the Torah and from Jewish leaders who inspire him to co-create a more inclusive Jewish community.

Rabbi Josh Gischner (he/him) is passionate about inclusion, accessible Jewish learning, justice, and artistic expressions of Jewish life and was ordained from the Hebrew Union College - Jewish Institute of Religion in May of 2021. Rabbi Gischner is one of the founders of Wrestling with Torah, and proudly serves as the rabbi educator at Temple Shalom in the DC area. Rabbi Gischner is excited to help you to discover your Torah.

Wrestling with Torah is a radically inclusive online Jewish learning community created by Rabbi Josh Gischner and Rachel Abrams in the Summer of 2020 to serve as a community for Jews and non-Jews, interested in exploring Judaism and their spirituality. WWT is dedicated to radically inclusive and financially accessible Jewish learning. Please email Rabbi Gischner at [email protected] in advance of this session regarding your accessibility needs and to introduce yourself!

#WWT#wrestling with torah#inclusion#accessibility#disability#lgbtq+#lgbt#queer#judaism#community#accessible#welcome#Betzelem Elohim#jumblr#class#workshop#torah#torah study#bible

313 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jews (and Muslims) in space! AKA fun with halakhic hypotheticals

@whiteraven13 asked:

Hi, I'm writing a sci-fi book that involves a long spaceflight before arriving on a new planet. How would being in space affect things like Shabbat (since no sundown) and praying towards Mecca? I want people's faiths to be important in the book because it always drives me up the wall when sci-fi stories are like "In the future people will be enlightened and won't need religion any more." Thank you!

Oh boy are you in luck, because this is actually something we talk about all the time! An astronaut in our current world doesn’t have the option of taking a full 25 hours off work, but they have in fact marked the beginning of shabbat by lighting electronic shabbat candles. Jewish astronauts have generally observed the shabbat times of their point of takeoff; lighting shabbat candles in orbit therefore has a set precedent.

We don’t yet have a precedent for which direction to face while praying; Judaism and Islam treat this issue differently, since in Islam they face toward the actual direction of Mecca, while in Judaism we face due east even in places where Jerusalem is to the West or North of us. My instinct says that on another planet we would face toward planetary East, but on a long spaceflight my thought is that we would likely not worry about what direction the Jewish prayer space faces, since we also have the convention of facing toward whichever wall the torah scrolls are stored on, regardless of which direction it is. Speaking of which, there has been a torah scroll in space, on more than one occasion.

Judaism has a lot to say about time. We don’t only mark the beginning and end of Shabbat at certain times, we also pray three times a day, at set times, and we observe holidays linked to the seasons--the seasons as they are in Jerusalem, regardless of which hemisphere of the Earth we’re standing on. It might be a jar for characters who have been observing the shabbat times of Houston for years to finally set down on a planet where their sense of time might be completely different--and narrative-wise, that’s not a bad thing: an American Jew stepping off a plane in Australia might have a similar experience.

The question of whether pork products created by a Star Trek style replicator would be kosher is open for constant debate: my gut says that when it came down to it there would be some people who do and some people who don’t accept the kosher status of a replicated pork chop, just as there is now for Impossible or Beyond fake-meat cheeseburgers.

Thank you for your discomfort with the trope of an enlightened future where the traditions of our ancestors have been eradicated, and for wanting to paint a picture of a better future, one where we are valued and given the resources and freedom to preserve and develop our living cultures.

- Meir

I agree with Meir - the good news is these are very realistic dilemmas and you will find lots of relevant commentary online; the bad news is, you will find a lot more questions than answers! But that’s also good news, because you can pick and choose the decisions and outcomes that suit your story. The line of reasoning will matter more than the conclusion.

Not much to add except I answered a slightly similar question with some pointers on things to google and why:

Jewish Character Stuck in Time Loop

Thanks for including our religion and culture in a highly technological future world 😊

- Shoshi

1K notes

·

View notes