#1840s doll dress

Text

Miss Beatrice Bear!

#sewing#handmade#plushie#teddy bear#1840s doll dress#I need to come up with a group name for all the animals in dresses#like…say hello to the latest member of the forest friends! the country cotillion? the pretty plushie pals#this would probably be easier if I knew more about 1800s fashion lol#I will come up with a name eventually#fancy forest friends? maybe?#my dad says I should name her Bunny. Bunny Bear#but I think I’ll just say Bunny is a nickname for Beatrice#she’s so soft and fluffy and adorable I’m so happy with how this pattern turned out

145 notes

·

View notes

Text

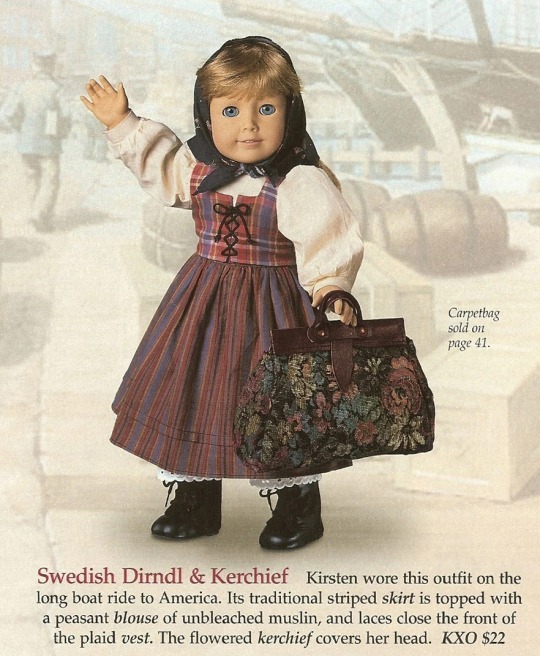

The Historical Accuracy of Kirsten's Dirndl

Despite its adorableness, I have seen many people complain about Kirsten's Swedish Dirndl outfit.

I would kill a man to have bought this for $22.

She wears this outfit for most of Meet Kirsten, being that she is an impoverished immigrant child who does not own any other clothes, and also for continuity reasons.

Frequently, I have seen it claimed that this outfit is not historically accurate and should not have been included as part of her collection. Conversely, I have also seen many German folk costumes marketed as being made for Kirsten. Both of these pain me a great deal (actually they just annoy me).

Nonetheless, I have decided to further procrastinate doing actual, meaningful work and instead set out on a new mission: figure out what the fuck is up with Kirsten's Dirndl.

In this post, I will lay out the research I have done, the evidence supporting the historical accuracy of this outfit, the challenges to its existence, and ultimately aim to answer the question of whether this outfit is one Kirsten plausibly could have worn on her journey from Sweden to America in 1854.

Let's begin.

First, the name. Pleasant Company/American Girl referred to this outfit as "Kirsten's Swedish Dirndl and Kerchief."

Unfortunately, there is no such thing as a Swedish dirndl. "Dirndl" is a German term, and refers to folk costumes worn by people in German-speaking areas of Europe (the Alps, Bavaria, Austria, and so on).

Kirsten is Swedish, and before Meet Kirsten has never left Sweden before. It is very unlikely she would have acquired, and regularly worn, a German dirndl. See this gorgeous example of a dirndl c. 1840:

Outfit, c. 1840. Munich, Bavaria, Germany. Münchner Stadtmuseum.

This ensemble is beautiful, but tragically, it is not what Kirsten is wearing.

What, then, is Kirsten wearing? What kind of traditional dress does Swedish culture have?

As it turns out, the proper term for what she is wearing is a folkdräkt. This is a Swedish term meaning "folk costume." Here is an illustration depicting multiple examples of Swedish folk costumes. In proper terms, these would be called "Svenska folkdräkter."

Nordisk familjebok (1908), vol. 8, Folkdräkt. Retrieved from runeberg.org.

These outfits are not quite identical to anything we see in Kirsten's collection, but you can observe various elements that have carried over -- the vertical stripes, black woolen skirts with ornate trim, and white dresses and red sashes (hello St. Lucia)!

Let us dive deeper. What do extant Svenska folkdräkter, specially those made c. 1850, look like? Is there anything like Kirsten's outfit among surviving examples?

Johan Sodermark, "Kvinna i dräkt."

In my few hours of research, this example image is the closest thing I have found to Kirsten's dirndl.

This lovely portrait is a watercolor from 1850 painted by Johan Sodermark. It is very creatively titled "Kvinna i dräkt" -- literally, "Woman in costume." The pattern of this woman's apron is incredibly similar to that of the skirt of the Kirsten doll's outfit -- a dark red base with blue and yellow stripes woven throughout.

Here is a closeup from the American Swedish Institute.

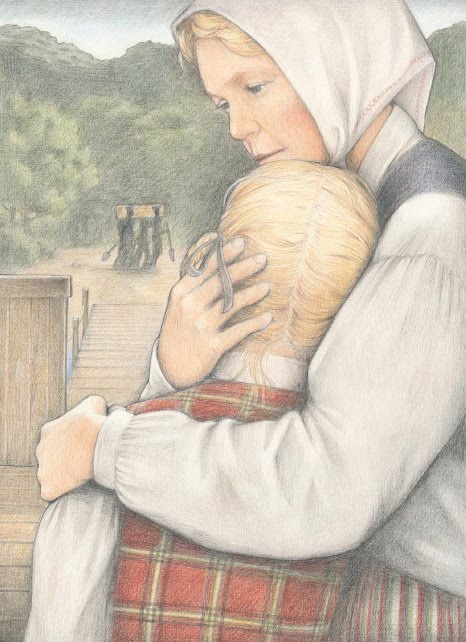

Although it is not shown in the doll-sized version of the outfit, the illustrations in Meet Kirsten by Renée Graef show us she also wears a light-colored, striped apron, which is almost surely the one that comes with her meet outfit.

Illustrations from Meet Kirsten, drawn by Renée Graef.

Notice the fabric of the bodice in the third illustration, though: Kirsten's top is made of red plaid fabric, while Sodermark's girl has an outfit full of stripes. Kirsten, bless her heart, spends an entire book outfit-repeating a potential pattern-mixing fail: plaid and two kinds of stripes and a floral scarf. Did Pleasant Rowland just hate her? Is Kirsten on another, elevated fashion plane far beyond my comprehension? Is there a historical basis for this combination of patterns?

I have no answer to the first two questions, but thankfully can speak on the third.

Komplett Vilskedräkt, Västergötlands museum. Some pieces c. 1865.

The top is plaid and laces up, which is not necessarily the most common way of fastening (in most examples, the bodice pins up), but it is a sensible choice considering both Kirsten's age (9) and the fact that Pleasant Company was making toys for little hands.

The model for the outer shell (the lace up top) belonged to Karl Edberg from Hällestad; it is not dated, but at least one piece of this set (the bag, which is not shown) is c. 1865. Additionally, the blouse here is very similar to the one that comes with Kirsten's winter outfit -- look at that keyhole neckline!

So, Kirsten's Dirndl outfit is actually very accurate as far as the clothing itself goes...the name remains the trouble.

I have no idea why they called it a dirndl. Folkdräkt is definitely challenging to pronounce, but why wouldn't PC just translate it as "folk dress" or "Swedish outfit" and call it a day? Why the insistence on referencing a culture that isn't relevant to the doll or her dress at all?

Perhaps this is a mystery to tackle for another day...

#kirsten larson#kirsten#american girl#pleasant company#meet kirsten#american girl kirsten#american girl dolls#agig#ag doll#ag dolls#american girl history#historical characters#1854#rambles#kirsten 1854#historical clothing#historical fashion#american girl analysis#renee graef#swedish historical fashion#folk dress#pleasant rowland#ag tumblr#ag on tumblr#american girl doll tumblr

344 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some pattern shops that aren’t owned by the Disney villain of doll sewing, and I’ve actually bought from them.

Good for beginners:

Appletotes, especially their basics like t-shirts and dresses. They also offer patterns for shoes and handbags as well as coats. Patterns include modern and 1970s styles.

Stella Sue for Dolls, modern girly dresses and outfits with some sleepwear

Easy to Intermediate:

Sofie Clareese Doll Fashion, mostly modern, with a couple of 1960s through 1980s patterns. Includes hats, outerwear, and Bitty Baby clothes

Noodle Clothing, primarily winter wear, a few summer dresses

Kotton Candy Patterns, dresses, one coat. It’s a fairly new shop

Farmcookies, mostly very girly/dressy dresses, they have a couple of Maryellen’s dress patterns (meet and unreleased school dress)

Dolls at Heart Patterns, mostly historical from Regency, WWII and 1970s periods, with some other eras including modern

My Angie Girl, girly dresses, pajamas, Halloween costumes

Read Creations, a wide variety of things from Viking dresses and Star Wars themed clothes to a KitchenAid mixer and English saddle. Tudor clothing, medieval knight armor, a life jacket, butter churn and more. She has some other free patterns on her blog.

Val Spier Sews, modern and early 20th century clothing

Bunny Bear Patterns, mostly 1930s and 1940s dresses

Lee and Pearl, ballet and skating outfits, career clothes. They have my favorite apron and medieval dress patterns.

Doll Tag Clothing, another shop with a wide variety of outfits, from medieval poulaines to animal costumes, cultural and career clothing

The Quirky Rabbit, Regency and Edwardian unmentionables

Confident Intermediate:

Carpatina, clothes from medieval period to present day, includes clothing from cultures other than European/American

Anne Van Doren Designs, historical clothing from Regency, Edwardian and WWII periods, including undies, shoes and bonnets. They have a glove pattern with defined fingers, for those who hate the mitten look.

Pemberley Threads, detailed historical clothes from the 1780s through 1840s, includes Regency boy’s clothing

Mother of Nine, Revolution, Regency and Belle Epoque dresses, character dresses from Sleeping Beauty, the Wizard of Oz and Frozen (shop is offline until January)

323 notes

·

View notes

Text

too many links on my vatore post so i had to do it on another post :')

because there's so many under a cut

IF YOU WERE TAGGED IN THIS POST ITS BECAUSE IT WOULDNT LET ME ADD YOU IN THE MAIN ONE. SEE IT HERE.

1810s: sunivaa's noel hair - peebsplays' collins outfit / gilded-ghosts' woodhouse bonnet + heywood bun + sensibility skirt + charlotte spencer jacket + hartfield boots

1820s: thesimsblues' regency brutus hair - historicalsimslife's authoritative aristocrat outfit / the-melancholy-maiden's antoinetta set - peebsplays' riding outfit

1830s: johnnysimmer's vevesims' elias hair update - happylifesims' vincent fashion set / the-melancholy-maiden's viola hair - moon-simmers' sunlittides dainty dress recolor - dancemachinetrait's caroline flats

1840s: johnnysimmer's chris hair / buzzardly28's cecilia hair - linzlu's fancy bonnet - oydis' esther dress historian recolor

1850s: kotcatmeow's daryl hair - batsfromwesteros' mid-victorian menswear + theroyalthornoliachronicles red recolor / buzzardly28's 1860s hair 3 (oops) - linzlu's birthday bonnet - simstomaggie's vire dress

1860s: moon-simmer's mr rochester suit (oops!!) / buzzardly28's penny hair - lace-and-honey's linzlu's prairie bonnet conversion - the-melancholy-maiden's antoinetta pearl earrings - linzlu's mary louise walking dress

1870s: plumbobteasociety's elm hair - linzlu's timely coat / i don't remember what hair i used but it was DEFINITELY one of buzzardlys!! - chere-indolente's flower bonnet - dzifasims' christine day dress

1880s: wheresbella's lucifer hair / buzzardly28's bridget hair - simsverses' hat with lily - javitrulovesims' meiji komorebi dress

1890s: vintagesimstress' 1896 cutaway frock / the-melancholy-maiden's late victorian hair and hat set - vintagesimstress' 1898 bella dress

1900s: historicalsimslife's edwardian casual suit / buzzardly28's sophie hair - chere-indolente's forma dress

1910s: cyber-frog-cc's modern man set / waxesnostalgic's small mushroom rose hat - elfdor's antique necklace - gilded-ghosts morning glories set (download here) - waxesnostalgic's edwardian french heels

1920s: happylifesims' suit with robe / the-melancholy-maiden's faux bob - hezzasims' pennyroyal cloche - emmastillsims' curbs' pearl recolors - happylifesims' 1920's day dress 7

1930s: cliffirem's noah hair - moon-simmer's feliciano jacket / vroshii's more 30s curls - plumbobteasociety's fiona sweater - twentiethcenturysims' marian trousers

1940s: plumbobteasociety's elbow patch shirt - moon-simmers bernando pants / twentiethcenturysims' gloria hair - gilded-ghosts sweet suspicions sweater + sleuthhound slacks

1950s: daylifesims' alex hair - vroshii's 30's shirt and shorts / glimersims' sugar hair - bustedpixels' vintage capri set

1960s: simadelic's curtain call hair / linzlu's 1960s basics top - pants - heels (download here)

1970s: polygraphish's dul incaru blouse - ridgeport's joe pants / kamiiri's phoebe hair - huiernxoxo's roxy pants

1980s: zombietrait's smith hair (download here) - deathpoke1qa's trad tank / kamiiri's juniper hair - serenitycc's haywood top - evellsims' fleabag pants

1990s: bloodmooncc's yulin hair - trillyke's full moon sweater - jellymoo's krueger jeans - sondescent's baby-doll shoes

2000s: sondescent's baby-doll shoes / dreambot's devils advocate hair - corporeal-ish scene scribble sneaks

2010s: o0corruptedghoul0o's adam side swept hair - zeussim's lavendel top - evellsims' these things skirt / bloodmooncc's pyretta hair

2020s: simomo's isamo hair - zeussim's skull earring - sforzcc's goosebumps dress / ms-marysim's roxy hair - dreambot's cute thing top

.. AND continuing thanks to @ridgeport @kamiiri @huiernxoxo @deathpoke1qa @serenity-cc @evellsims @jellymoo @sondescent @dreambot @o0corruptedghoul0o @zeussim and finally @ms-marysims

13 notes

·

View notes

Note

idk if you've posted them before but can u show us all the dolls?

I can do my best!

Top row, left to right: Marinette (fashion doll by the Francois Gaultier firm of Paris, in original clothing, c. 1880), Sarah (Armand Marseille model “1894″ doll, made in Germany around the year of her mold name), Victoria (1980s porcelain doll given to me by a dear friend some years back).

Bottom row, left to right: Celine (wax child doll, probably made in Germany c. 1870s, seriously damaged), Clara (wax child doll, also probably German, also damaged, c. 1860s), Em (another damaged probably-German wax doll from the 1860s), Magda (German wax lady doll, 1860s). On their laps are China (original pink dress, 1880s china doll made in the U.S. of German bisque parts and a domestic-manufactured cloth body) and Flora (original cream dress, wax-headed doll probably made in England c. 1840s-50s).

Top, seated: Maryse (modern ball-jointed doll by Canadian artist Marina Bychkova, face painted by Jay Searle, outfit- unfinished -by me).

Standing: Jeanette (1870s French fashion doll by the Francois Gaultier firm mentioned above, original undergarments.)

Left to right: Rosamond (1955 Madame Alexander “Cissy” fashion doll wearing an early 1960s “portrait” dress by the same company), Leonore (seated, late 1860s French fashion doll by the Dehors firm of Paris, outfit by me), Barbie 5 (#5 ponytail Barbie c. 1961), Barbie 3 (#3 ponytail Barbie c. 1959-60), Draculaura (collectors’ Monster High “Draculaura” doll, modern), Isabelle (seated, modern BJD by French artist Lillycat, “Chibbi Lana” sculpt), Margaret (1860s china dollhouse doll, behind held by Isabelle).

That little cream blob at the feet of Barbie 5 is Lydia, another 1860s china dollhouse doll. She has TINY BLUE BOOTS, which is Very Important.

And that’s about all the ones I’m not currently trying to sell!

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

my very hypothetical wedding plans!

(i am but a child and have not ever had a relationship, but i love romance and thinking about these sorts of things!)

morning of timeline:

5:00 a.m. - 6:00 a.m. morning routine

6:00 a.m. - 7:30 a.m. gather decorations/other things

7:30 a.m. - 8:00 a.m. last minute things

8:00 a.m. - 8:45 a.m. travel to venue

8:45 a.m. - 11:45 a.m. caterers arrive and set up

8:45 a.m. - 11:45 a.m. wedding party gets dressed

arrangement calls and confirmation should have been set up the week before. the venue should have been set up the day before. eat light breakfast. wear white vintage slip/nightgown.

wedding timeline:

12:00 p.m. - 12:30 p.m. portraits and family pictures*

12:30 p.m. - 12:45 p.m. guest arrival and seating

12:45 p.m. - 1:00 p.m. ceremony

1:00 p.m. - 1:30 p.m. cocktail half hour

1:30 p.m. - 2:30 p.m. lunch

2:30 p.m. - 2:45 p.m. cake

2:45 p.m. - 3:00 p.m. toasts

3:00 p.m. - 3:10 p.m. first dance

3:10 p.m. - 7:00 p.m. dancing/activities

ceremony and reception are in the same place. venue is most likely a mansion in the suburbs. the ceremony will be set up with dinner tables on either side of the aisle with the arch at the end. i will have a flower child and ring bearer. for the cocktail half hour, guests can just talk, or enjoy the activities, and eat the little snacks. toasts are done by parents of both newlyweds and maid(s) of honor/best man/men. i would prefer only a first dance and no parent dances, but i guess we’ll see what my future spouse wants. lunch is plated and guests selected which meal option they wanted on the rsvp i think. cake will be fully cut and put on plates and put in front of everyone. they will not be able to resist the lemon curd/other fillings!!!!! then dancing can start and the non-dancers can enjoy board games, cards, toys, books, and polaroid cameras. even if someone is completely alone and has no one to talk to (which i really hope isn’t the case!), they will probably be able to enjoy themselves with activities and taking pictures of other people. for an “after party” we’ll probably go to the hotel/airbnb of someone who had to fly in.

*photographs wanted:

things

signs and stuff, rings, bouquet closeup, wide venue shots (ceremony and reception), wedding cake, food shots, decor details, people (portraits), my whole family, future spouse's whole family, couple alone, me and my half of wedding party + flower child/ring bearer, future spouse and their half of wedding party + flower child/ring bearer, couple with entire wedding party, couple with both sets of parents, and flower child and ring bearer together (<33).

people (action)

both parts of the wedding party getting ready, walking down the aisle, exchanging vows, kiss, cake cutting, cake eating, people dancing and having fun, and children specifically having fun.

days?

maybe the sunday before martin luther king day or around valentine’s day..

attire

custom tailored 1840’s style white gown. i could just select some textured white fabric and the whole dress could be made of it with some lace trim on the sleeves, hem, and maybe neckline.

(by the way, i need to get botox in my underarms during the engagement period.)

carved gem ring with something that's significant to the relationship. like each other's eye colors or something that symbolizes the place we met.

paper

i will design the invitations. making them digital would be a great way to save money, but i like the idea of sending physical invitations.

decor

possible themes:

lake of lily pads (frogs, swans, and ducks)

meadow of horses

soft delicate valentines day

enchanted forest

strawberries and lovecore

angels/heaven

cakes and princesscore

antique dolls

“somewhere that's green” from little shop of horrors

land of light and rain

cherished teddies

fabric flowers and patterned or solid colored linens (not white, most likely) to match the theme. centerpieces and signage designed by me to match the theme. little thrifted knick knacks and wares placed on tables to match the theme.

thirteen tables, eleven of them have eight chairs and two have seven chairs. one hundred guests, plus the couple. although there’s also a sweetheart table.

thrift/purchase a theme-matching tea pot (and coffee pot?) for each table, rent colored glasses and theme-matching plates.

food

for the cocktail half hour, there's a table of treats and snacks for people to eat.

i want a plated meal with at least one vegan option and at least one gluten free option. they'll all be pasta.

for cake, i'd like three tiers with white mascarpone frosting and lemon curd/strawberry cream/peaches inside!

activities

chess, checkers, standard 52-card decks, and tarot cards.

toys

these would be for children and others to amuse themselves with and they'll be wedding themed in some way, but the exact toys will have to be based on what theme i decide on....

1 note

·

View note

Text

NaNoWriMo 2022: Day 27

I didn’t post the update yesterday because it was mostly sex scenes. Yes, really.

None of this is written in order and it’s supposed to depict most of the main character’s life. Yesterday’s writing is like 25 years after today’s writing on the time line. Basically, I go with whatever idea I have that day to write about. Again, this will be a beastly mess to edit. So many loose ends to tie up! ;-;

So instead have this story when little Matilda meets her first butch woman, Miss Penney Smythe, a classmate of her mother’s from her finishing school. They’re all upper middle class Victorian women. Rosie was born in 1848 and Matilda 1850 (roughly) so this is from about 1855. Their Mother and Miss Smythe were both in finishing school in the early 1840′s as girls.

Day 27 word count: 1,935 Words

Total word count: 80,943 Words

Excerpt:

I'll take you back as far as I can remember. Johnny was just a baby, not but two years old. I doubt he can remember. I was nearing five myself and Rosie was going to turn seven. Charlie was the baby in Mama's stomach at the time. There are few memories I have when my brothers aren't yet born. Those are even hazier than this one.

This one sticks out to me because it happened around the time Miss Holburn first became Rosie's and my governess. Papa got a new Coachman around that same time, a kind gentle soul named Dave. But neither of them had much to do at with the arrival of this third person who came to call on my mother when Papa was out on business. Rosie and I did find her a person of interest; she was a jolly woman who wore pants, a man's vest and jacket. Apparently, she was a classmate of Mama's when they went to finishing school.

"Miss Penney Smythe, let me introduce you to my daughters, Rosalie-" my sister curtseyed when mentioned "and Matilda." I bowed instead much to Miss Smythe's delight.

"Well, it's my honor to meet you, Miss Murray and Miss Matilda." She took off her hat, a top hat with a feather in it. I was shy around her because I didn't know women like her could exist. I would purposely go to the drawing room where Mama and her guest talked just to look at Miss Smythe. I was mesmerized.

Rosie, wanting attention, brought out her dolls to show Miss Smythe who kindly entertained Rosie's display. Not wanting to be outdone- I also brought my favorite doll- a doll Papa bought for me at my last birthday, but Mama didn't much like. You see she was a soldier and she fought in the American Revolution. Papa found this story charming. I named her Deborah Sampson after the solider herself. I saw her in one of Papa's books. One of his friends was an American and he brought that book, with many pictures, for Rosie, Johnny and me to share. I liked to pour over it even though it wasn't our history; it was still the story of another nation's past.

Papa found me a funny child because I liked old stories and tales of men and women who lived long ago. My mind was awash with knights and princesses, faraway lands and events long forgotten. I retold these stories to Rosie who loved to be the princess in all of them. Naturally, she was and I would be anyone else in the story. Rosie and I danced in the nursery, pretending we were at a masquerade, looking for our enemies on all sides.

"I don't trust Duke Champlain. He might be in on the plot to murder our mother, the queen." Rosie said to me as we danced together in the imaginary ball room. We made silken masks and small capes from one of Mama’s old dresses to go to the imaginary masquerade.

We were twins in this rendition of the game. She was the lovely, fair Princess Rosie and I was her protective brother, Prince Matthew. Granted, we made much fuss over all these details which Rosie wrote down in our shared notebook. She had better handwriting than me and I didn't want to make a mess of our book.

#nanowrimo#nanowrimo 2022#word count#writeblr#my writing#victorian era#victorian lesbians#tilly: the progress of a victorian lesbian and female husband#lesbian characters#lesbian writer#Penney Smythe is the first lesbian that Matilda meets#that she's aware of anyhow#both Miss Holburn and Coachman Dave are also lgbt#good luck with your projects everyone else!#we have three days to go#I can't believe it's almost December already! :O#b. h. avondale

1 note

·

View note

Text

“The outcry over commercial beauty preparations focused especially on the morality of masking or transforming features and raised anew longstanding questions about women's nature and social role. Powder and paint had always been more identified with the feminine than the masculine in Anglo-American culture, but in the eighteenth century, their use was as much a matter of class and rank as gender. In England, enamel, rouge, white powder, masks, and beauty patches were instruments of fashion that covered pockmarks, drew attention to good features, and served as props in the spectacle of court society and posh urban life. Elite colonists of both sexes imitated the aristocratic mode and sought the grooming aids of apothecaries and hairdressers. Powder and paint proclaimed nobility and social prestige, as essential to fashionable high culture as ornamental clothing and tea drinking.

A challenge to this view came during the American Revolution. In a republican society, manly citizens and virtuous women were expected to reject costly beauty preparations and other signs of aristocratic style. The transformation in self-presentation was most pronounced in men, who spurned luxurious fabrics, perfume, and adornments as effete and unmanly. In a personal declaration of independence, Benjamin Franklin discarded his periwig. The "great masculine renunciation," as fashion historians call it, replaced spectacular male display, once considered an essential symbol of monarchial rule, with a subdued and understated appearance. Republican ideals of manly citizenship reinforced the idea: Men need not display their authority, since their virtue was inherent. The democratization of American politics after 1830 further advanced the new view of male self-presentation.

The point of no return may have occurred in 1840, when Representative Charles Ogle, in a speech before Congress, attacked Martin Van Buren's presidency and his manhood by ridiculing the toiletries on Van Buren's dressing table. Corinthian Oil of Cream and Concentrated Persian Essence no longer endorsed the gentleman of rank but intimated the emasculated dandy. As a mercantile and manufacturing class gained power, businessmen avoided artificiality in appearance in an effort to gain trust in the marketplace. In turn, men who adorned their features were treated with contempt. Novelist Sara Willis, for instance, disdained a "be-curled, be-perfumed popinjay"; Walt Whitman said of a "painted" man on Broadway, with "bright red cheeks and singularly jetty black eyebrows," that he "looks like a doll." Of course men continued to pay attention to the mirror. Shaving paraphernalia, hair dyes and “rejuvenators," bay rum and brilliantine were all sold on the market throughout the nineteenth century.

Barber supply catalogues featured face washes, colognes, tinted talcum powders, and "cosmetique," a perfumed waxy substance used to touch up gray hair. Except for shaving and hair care, however, cosmetic practices among men became largely covert and unacknowledged. Women also were encouraged to shun paints and artifice in the service of new notions of female virtue and natural beauty. Early nineteenth-century literature bound the feminine to ideals of sexual chastity and transcendent purity. These views took root under the growing authority of the middle class, which perceived beautifying as the "natural disposition of woman," but only as it reflected those feminine ideals. A belief in physiognomic principles, that outer appearance corresponded to inner character, underlay these views and echoed the earlier belief in humoralism.

Reinvigorated by Johann Kaspar Lavater in the 1780s, physiognomy and its nineteenth-century cousin phrenology claimed to reveal personality through the study of facial and bodily features. These pseudosciences classified men in terms of a diverse range of occupations and aptitudes. When it came to women, however, their subject was solely beauty and virtue. Thus physical beauty originated not in visual sensation and formal aesthetics, but in its "representative and correspondent" relationship to goodness. Assessments of female beauty, however, often unconsciously reversed the physiognomic equation, submerging individuals to types and reducing moral attributes to physical ones. Hair, skin, and eye color frequently stood as signs of women's inner virtue. The facial ideal was fair and white skin, blushing cheeks, ruby lips, expressive eyes, and a "bloom" of youth-the lily and the rose.

Although some commentators disagreed, most condemned excessive pallor or coarse ruddiness. Nor was the ideal an opaque white surface, but a luminous complexion that disclosed thought and feeling. If beauty registered women's goodness, then achieving beauty posed a moral dilemma. Sisters Judith and Hannah Murray neatly captured the middle-class viewpoint in their 1827 gift book, The Toilet, made by hand and sold for charity. Each page carried a riddle in verse and an image of a cosmetic jar, mirror, or other item typically found in a lady's boudoir. The pictures were pasted onto the page in such a way that when lifted, they revealed the answer to the puzzle. "Apply this precious liquid to the face / And every feature beams with youth and grace." A pot of "universal beautifier"? No, the secret lay in "good humour." In like manner, the only "genuine rouge" was modesty, the "best white paint" innocence.

These riddles must have had a wide appeal. Harper’s Bazaar described an "old-fashioned" fair in 1872, where a girl sold for a dime little packages "said to contain the purest of cosmetics"-the Murrays' moral recipes. The Murray sisters acknowledged the allure of cosmetics in elegant bottles, but maintained that only virtue could produce the effects they promised. Even so, their gift book reinforced the widespread belief that beauty was simultaneously woman's duty and desire. Godey’s Lady's Book, the arbiter of middle-class women's culture, took up the theme, advocating "moral cosmetics" in tales of sad appearances transformed by plain soap and clean living. In "Lucy Franklin," an unattractive woman whose complexion combined the "colour of dingy parchment" with a "livid hue" becomes lovely under the guidance and friendship of an older woman. Happiness, the story concludes, is "a better beautifier than all the cosmetics and freckle washes in the world.”

Etiquette books addressed to African Americans, published later in the nineteenth century, similarly distinguished between cosmetic artifice and the cultivation of real beauty from within. Mary Armstrong, training Hampton Institute students to display signs of middle-class refinement and modesty, considered the use of visible cosmetics disgraceful. "Paint and powder, however skillfully their true names may be concealed under the mask of 'Liquid Bloom,' or 'Lily Enamel,' can never change their real character, but remain always unclean, false, unwholesome," she insisted. Nothing was more essential to beauty than self-control and sexual purity. "Those who are in the habit of yielding to the sallies of passion, or indeed to violent excitement of any kind," cautioned Countess de Calabrella, "will find it impossible to retain a good complexion." Management of emotion nevertheless coexisted with "management of the complexion," as one guide called it: pinching cheeks or biting lips to create a rosy hue, or wearing colors, especially in bonnet linings, to produce the optical effect of lightening the skin.

The ideal of pure, natural beauty disguised the way women's appearances were in fact dictated by middle-class cultural requirements. The new feminine ideal challenged but did not entirely displace earlier perceptions of women as sexually corrupt, deceitful, and vain, vices that face paint had long signified. In his 1616 Discourse Against Painting and Tincturing, Puritan Thomas Tuke had endorsed the use of washes made with barley, lemons, or herbs, the cosmetics of domestic manufacture. But, he warned, "a painted face is a false face, a true falshood [sic], not a true face." Women who painted usurped the divine order, as poet John Donne put it, taking "the pencil out of God's hand." Indeed, some viewed the cosmetic arts as a form of witchcraft. The specter of "designing women" led the English Parliament in 1770 to pass an act that annulled marriages of those who ensnared husbands through the use of "scents, paints, cosmetic washes, artificial teeth, false hair, Spanish wool, iron stays, hoops, high-heeled shoes and bolstered hips."

That a woman with rouge pot and powder box might practice cosmetic sorcery suggests both an ancient fear of female power and a new secular concern: In a rapidly commercializing and fluid social world, any woman with a bewitching face might secure a husband and make her fortune. Nineteenth-century moralists continued to view face paint as "corporeal hypocrisy," a mask that did not conceal female vice and vanity. They invoked Jezebel, the biblical figure who represented the dangerous power of women to seduce and arouse sexual desire. Painting her eyes with kohl and loving finery, "Oriental" Jezebel was "the originator and patroness of idolatry," whose arrogance and pride brought death and destruction. Her example taught that women had a duty to spurn adornment, submit to authority, and cultivate piety. To most Americans, the painted woman was simply a prostitute who brazenly advertised her immoral profession through rouge and kohl.

Newspapers, tracts, and songs associated paint and prostitution so closely as to be a generic figure of speech. In New York, "painted, diseased, drunken women, bargaining themselves away," could be found in theaters, while in New Orleans, "painted Jezebels exhibited themselves in public carriages" during Mardi Gras. Mining camp balladeers sang: Hangtown Gals are plump and rosy, Hair in ringlets mighty cosy. Painted cheeks and gassy bonnets; Touch them and they'll sting like hornets. The older view of the painted woman informed the efforts of the middle class to distinguish itself from a corrupt upper class. In Godey's Lady's Book, face paint and white washes often appeared as the potent temptations of dissolute high society to be avoided by respectable young ladies. New York journalists at mid-century exposed the "ultrafashionable" woman as all art and no substance.

James McCabe offered a typically harsh assessment in 1872: She is a compound frequently of false hair, false teeth, padding of various kinds, paint, powder and enamel. Her face is "touched up," or painted and lined by a professional adorner of women, and she utterly destroys the health of her skin by her foolish use of cosmetics. . . . So common has the habit of resorting to these things become, that it is hard to say whether the average woman of fashion is a work of nature or a work of art. Lurid accounts described the "enamelling studio" as a den of female vice, where fashionable women could "get their complexions 'made up' by the 'quarter' or 'year.'” The enameller first "filled up the ugly self-made wrinkles and the natural indentations, with a plastic or yielding paste," wrote photographer H. J. Rodgers. "Then the white enamel is carefully laid on with a brush and finished with the red."

Cosmetics and paints marked distinctions between and within social classes; they also reinforced a noxious racial aesthetic. Notions of Anglo-American beauty in the nineteenth century were continually asserted in relation to people of color around the world. Nineteenth century travelers, missionaries, anthropologists, and scientists habitually viewed beauty as a function of race. Nodding in the direction of relativism-that various cultures perceive comeliness differently-they nevertheless proclaimed the superiority of white racial beauty. Some writers found ugliness in the foreign born, especially German, Irish, and Jewish immigrants. Others asserted the "aesthetic inferiority of the ebony complexion" because it was all one shade; Europeans' skin, in contrast, showed varied tints, gradations of color, and translucence. And because appearance and character were considered to be commensurate, the beauty of white skin expressed Anglo-Saxon virtue and civilization-and justified white supremacy in a period of American expansion.

Aesthetic conventions reinforced this racial and national taxonomy. Smithsonian anthropologist Robert Shufeldt, for example, classified the "Indian types of beauty" in North America in an illustrated 1891 publication. The women he considered most beautiful were posed as Victorian ladies sitting for their photographic portrait. In contrast, the camera rendered those he classed as unattractive in the visual idiom of ethnography: haIf-naked bodies, direct stare, and frontal pose. Tellingly these women also used paint on their faces and hair, which to white critics illustrated the "lingering taint of the savage and barbarous." According to Darwinians, the use of paint even impeded evolutionary progress: If men used visuaI criteria to choose the best mate, cosmetic deception thwarted the process of natural selection. A light complexion preoccupied not only the educated in science and letters, but was the governing aesthetic across the social spectrum.

…No one defined the antipode of the dominant American beauty ideal more starkly than African Americans. Kinky hair, dirty or ragged clothing, apish caricatures, shiny black faces: White men and women had long invoked these stereotypes to exaggerate racial differences, dehumanize African Americans, and deny them social and political participation. In the antebellum period, slaves audacious enough to cross over into the white mistress's "sphere" of beauty and fashion endured severe punishment. Delia Garlick, for instance, recalled the beating she received when she imitated her mistress's cosmetics use: "I seed [her] blackin' her eyebrows wid smut [soot] one day, so I thought I'd black mine jest for fun. I rubbed some smut on my eyebrows and forgot to rub it off, and she kotched me." The mistress "was powerful mad and yelled: 'You black devil, I'll show you how to mock your betters.'” Picking up a stick, she beat Delia unconscious.

For this Southern mistress, fashionability, including the use of beauty preparations, underscored the class and racial hierarchy of the plantation. Significantly, she refused her slaves "clothes for going round," providing only "a shimmy and a slip for a dress"; "made outen de cheapest cloth dat could be bought," such clothes were a badge of slavery. By beautifying herself, Delia had defiantly claimed recognition as an individual and a woman as she burlesqued her mistress's feminine airs. Continually made aware of the social significance of appearances, nineteenth-century African Americans understood the power and pleasures of "looking fine" in the face of destructive stereotypes. Yet, observed antebellum author Harriet Jacobs, herself a former bondswoman, physical beauty contained a cruel irony, for it inflamed white men's sexual abuse of black women.

Racist representations proliferated in the latter half of the nineteenth century. Evolutionary science fitted African-American bodies into new visual classifications of inferiority based on facial angles and physiognomic measurements. Trade card advertising and minstrelsy caricatured the plantation slave's appearance to negate black Americans' efforts to define themselves as modern and self-respecting. One minstrel song, "When They Straighten All the Colored People's Hair," mocked an increasingly popular form of hair styling. For white Americans, sustaining a visual distinction between white and black masked an uncomfortable truth, that Africans and Europeans were genealogically mixed, their histories irrevocably intertwined. In advice manuals and formula books, white fears of losing their superior racial identity underwrote old anxieties about cosmetic artifice.”

- Kathy Peiss, “Masks and Faces.” in Hope in a Jar: The Making of America's Beauty Culture

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Opinion on Tight-Lacing as Depicted in Period Pieces

So, I'm writing this as someone who is not a historical costumer, but who enjoys learning about historical clothing and also reads/watches a lot of historical fiction. (I do make clothespin dolls with historical costumes, but a little cylinder-shaped wooden doll doesn't have much use for corsetry.) This is also focused on period pieces set in Europe (mostly England) and the USA (colonial to 1910s).

In general, the "historical woman is laced as tightly as possible into a corset and can't breathe" trope is so well-worn that only historical accuracy can make me smile upon it wholeheartedly. There are fresher ways to indicate that a character is struggling against rigid standards of beauty, and there are many eras where support garments were either minimal or not particularly restrictive at the waist. However, some inaccuracies are much sillier than others. Let's break it down:

Antiquity: I've never actually seen the Tight-Lacing Scene in a pre-medieval period piece! That'd be pretty silly in most contexts, although I guess you could do something with the Minoans and it wouldn't be completely nonsensical. Just very speculative, given the dearth of information on the Minoans in general.

The Middle Ages: There's a little bit of evidence for minimal support garments (wrapping up one's boobs, mostly), and a few fashions of this very long period of time were pretty tight-fitting. If a late medieval heroine were to complain about her gown being laced too tight, I'd be like, "Fine." However, the Tight-Lacing Scene (involving an actual corset) is only acceptable in a vaguely medieval, deliberately anachronistic Shrek-like movie (in which the characters are also wearing figure-hugging clothes). Beyond that, it was too silly even for Brave.

The 300-ish Years after the Middle Ages Ended but before the Empire Waist Came into Fashion: This is a fairly long stretch of time with many different fashions, but support garments that went around the waist were widespread, and silhouettes that emphasized the natural waist were common. If the creator can make it make sense using the specific garments and beauty standards of the era, I have no issue with this being in a period piece (although I still think there are more specific, creative options in most cases). However, if they're just going to put a late-Victorian-looking corset into the scene, that should be limited to movies set in the vague past that share some aesthetics with an era in this range (like many Disney movies).

The Empire Waist Era: Just think about this for five seconds. Why would you make your waist as tiny as possible, just to hide it inside a voluminous tube of fabric? Too silly for Shrek.

The Small Waist, Big Skirt/Sleeves Era (Roughly Mid-1820s to Mid-1870s): Unless a movie or show is touting itself as The Most Historically Accurate (about clothing or otherwise), the Tight-Lacing Scene is okay by me. Yes, wide skirts and huge sleeves were the favorite ways to make the waist look small, but it's not implausible that someone would also wear their corset very tight to achieve that effect. Once we get into the 1840s, I think even a movie with higher ambitions can support this.

The Late Victorian and Edwardian Eras: This is the natural home of the Tight-Lacing Scene, and unfortunately I think some corset aficionados have let their exhaustion with less-justified uses of this trope negatively affect their view of all examples. Corsets were pretty restrictive at this time, and the use of corsets was a hot topic for a lot of people. (How tight should a corset be? Should anyone wear a corset? Should children wear corsets? Can women and girls please wear something more comfortable to play sports in? What kind of denial was Ma Ingalls in to complain about her hardy farm-laboring daughter choosing not to sleep in a corset?) It'd be cool if more of these period pieces acknowledged the dress reform movement, though.

Post-Edwardian: I haven't seen any movie set after WWI where people wear corsets (unless they're wearing a costume or being sexy). Really, I haven't seen a lot of 1920s-1960s period pieces where women are like, "Fuck this girdle/bra," even though women were expected to wear such things and sometimes very vocally disliked it. It's probably too similar to our support garments.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Getting dressed in 1846! (...because I love fashion history)

This dress (from DollClothesByMenay on Etsy!) is quite long for a ten year old, but let’s just say it’s for a formal occasion like a recital or a party, where Cati wants to feel very grown up. The shape of this dress, with its wide neckline and low puffed sleeves, was very popular in the late 1830s and early 1840s. Before this, huge, high-puffed sleeves were all the rage. By the mid 1840s, a straight, tight sleeve and a high neckline were more popular, then the bell-style sleeve became popular in the late 1840s, especially in the USA. (Addy’s original school outfit has this style of sleeves.) Of course, most people don’t throw away their entire wardrobe every time fashion changes, so Cati would still have worn this dress in 1846 and, most likely, would have it altered to fit the newer style, rather than dishing out to have a new dress made. The waistline of this dress is close to the body’s natural waistline; if you look at the transition from 1770s to 1850s, the fashion goes from natural waistline to empire (or just below the bust) and back again really quickly compared to the usual timeline for major silhouette changes in women’s fashion. Whether you like the look of Regency/Jane Austen/Empire era fashion (1790s to early 1830s) or not, it’s so interesting to study how it appeared, became ubiquitous, then completely faded out, all within about a 30 year period. The late 1830s and the 1840s were when the last remnants of Regency fashion transformed into typical early/mid-Victorian fashion.

Her hair is in a style popularized by Queen Victoria of England, two braids in the front that loop into a low bun at the back.

This petticoat came with the dress, and supports it beautifully. But to be more historically accurate, Cati would wear several petticoats: first, a simple one, then a corded petticoat (the precursor to the hoop skirt/steel cage crinoline that would be patented in 1856, leading to the massive skirts of the Civil War fashions - before, skirts could only be poofy with layers and layers of petticoats, but weight and heat limited how many could realistically be worn. Funny enough, 18th century panniers were very similar in design to the hoop skirt, as was the 16th century farthingale). She would most likely wear another petticoat on top of the corded petticoat, to conceal any lines or bumps the cording made.

Since Cati is only ten, and her mamá isn’t extremely traditional, she doesn’t wear any stays yet. If she were older, she would wear transitional stays, longer and more structural than the short stays of the empire-waisted Regency fashions, but less shaped than the corsets of the later Victorian era that made a small waistline by enhancing the hips and bust.

So, no stays for Cati, but she does wear a shift (thank you, Felicity). This style of shift or chemise was the standard for centuries (with variations in length, neckline, and sleeve length), but during the latter half of the 19th century, there’s a trend towards increasingly lacy and often sleeveless chemises. By the early 20th century, the standard chemise is sleeveless, but some women wore a pair of combinations, rather than a chemise and split-leg pantalettes/drawers.

Speaking of pantalettes, here are Cati’s! They came from an old porcelain doll and are a bit snug around her legs. To be more historically accurate, they would be made out of linen or cotton, would reach the tops of her ankles, and would not be joined at the crotch, for easy bathroom access. For most of history, women’s undergarments didn’t include anything between the legs, just skirts. Split-leg pantalettes gained popularity first in children’s clothing, but became adult women’s wear during the Regency period, where skirts were less full and closer to the body.

Under her pantalettes, she wears knit stockings. They come up just past her knees and would be tied in place with a ribbon garter (silk or linen, to grip the stocking) above or below the knee. Her shoes are from CR’s crafts, and mimic extant shoes I’ve seen from this period. I’d like to get her some side-button boots, but haven’t found any I really like yet. As long as she doesn’t do anything more strenuous than music lessons and dancing, she’ll be fine with her dainty slippers.

That’s it! I absolutely love fashion history and how everything changes over time, so I hope some of y’all enjoyed reading this! If anyone else is into this (or not) and wants to add (or correct, I’m not an expert, just a hobbyist) anything, please do!

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

The first doll dress for my 18” doll! It still needs snaps but I’m going to wait to sew them on until the doll arrives, so that I can tweak the fit a little if needed

#sewing#handmade#doll clothes#1840s doll dress#tj makes doll clothes#(that’s my new tag for all the 18 inch tall doll stuff)#(1/12 scale doll stuff remains in the hypothetical dollhouse tag)#the pattern says it’s 1840s I’m not saying that#I absolutely cheated and used minky to make it way easier to make#I did not expect it to work up so quickly?#I mean it’ll take a lot longer when I make another one out of woven fabric#with all the ironing and finishing off edges and sewing a lining#(all things I did not do for this one)#but still! I was worried it’d be like a multi day project#not an afternoon project#this one only took and hour and a half to sew. that’s not counting the time for cutting out the fabric or sewing in the snaps#so it’ll probably be closer to two or two and a half hours total#but still! pretty quick!

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is my OC Wednesday (+ her doll, Dolly)! I think I may have posted her before but here is here updated design! Her story is closer to the bottom of this if you wanna read it (it’s not too long, don’t worry!)

Info:

Name: Wednesday Stewarts

Age: 10 (when alive)

Species: Vengeful spirit

Death: Hanging

D.O.B: April 5th, 1840

D.O.D: July 3rd, 1850

Location: England

Appearance:

Hair: Short, brown hair

Eyes: Blue, almost grey, eyes (alive)

No eyes (dead)

Face: Crying blood, due to the force of the rope exploding her eyes when she died, and pale white skin

Outfit: Yellow dress, with a white collar, belt and sleeve cuffs, a light brown bow around the neck and either brown sandals, with yellow straps, or shoeless

Possessions: A ginger (almost red) woollen haired doll with a baby pink dress and white skin, all covered in patches of slightly darker shades, a rope and a picture of her parents

Story:

Wednesday and and her big sister Elizabeth (aka Ellie) were sisters. Although their five year difference in age, they looked incredibly alike. Ellie had always been rather short, making her quite close in height to her sister. Their family was incredibly close, though recently, Ellie had been a lot more distant. Their mother, Catherine Ann Stewart, decided to sew the two identical dresses. Wednesday, Elizabeth and their mother decided to walk through the forest while their father, William Stewart, was at work sweeping chimneys down Redbury Lane. After their walk, they decided to return home and wait for him to return while their mother was cooking dinner. After dinner, they all went to sleep. Ellie grabbed the closest outfit to her, the sisters’ identical dress, and sneaked out. She killed 3 people before being caught by a man and speedily running into the forest. The next morning, just after 9am, the family awoke to the loud bangs of the mob trying to find this short girl in a yellow dress. The family realised Ellie was gone and got dressed in anything they could find, Wednesday putting on her yellow dress the was folded in the basket, as well as quickly grabbing Dolly, who has a picture of her parents hidden under the dress. They ran out to look for Ellie and the man instantly saw that dress and decided that she must have been the one to have killed them. The town dragged her to the middle of the forest, where she got hung publicly for her sister’s crime, still hugging Dolly. She now hunts the ancestors of her sister, that man and the rest of the people who watched. She lures them into the beautiful, flower filled forest clearing where she was hung, pretending to be a lost, scared child, convinces them to stand on a rock under a tree, where she will push them off and they will be hanged to death without even realising until it was too late. The town believes that the suicide rate has just increased more and more over the years as superstition began to decrease and Wednesday was forgotten. She does, however, spare those she believes do not deserve what she also did not deserve. Although, she will kill them in the future if they change for the worse in any way. As children, she hangs round them like an imaginary friend. She plays with them, helps them out, hoping they won’t become anything like who she knew. However, she isn’t always able to prevent it. She loves to play games and loves to bake with the children, even if she has to struggle to make sure their parents don’t find out. She still loves her own parents and always will.

#art#oc#original character#creepypasta#creepypasta oc#redesign#oc redesign#Wednesday Stewarts#artist#Traditional art#original child character#original art#original content#original character design#character design#characterillustration#own character#my characters

0 notes

Note

Hello Vince! I've been researching these questions for a while to no avail and was wondering if you had advice, as a fellow trans person into historical fashion. The first, is that as a nonbinary person I'd like to make clothes with an androgynous/genderfuck silhouette but am not sure how to achieve that, if you have any tips.(1/2)

The second, larger problem, is that as a nonbinary person, I have a “nonstandard” body. I’m dfab and have had top surgery but am not on T. I am quite short (5'2") with wide hips. My attempts at drafting patterns and making mockups from men’s patterns have gone atrociously (I was attempting some 1908 breeches.) How have you found success in making/drafting historical clothing with a trans body™? (2/2)

Hello! Ok. First thing you need to know is that there’s no such thing as a “standard body”. It’s not a thing, and it never has been.

Clothing companies may try to pretend it is, but all they’re doing is making stuff that kind-of-sort-of fits a lot of people, but hardly fits well on anybody at all. (The same is true of commercial sewing patterns, although there is much more potential to change stuff with those.) Look around and you’ll see that people come in an infinite variety of shapes and sizes. Different heights, different weights, different proportions, and varying degrees of asymmetry.

Mass produced garments are going by statistical averages, and people just come in too many shapes to make that work. It’s why I have a job doing alterations for a suit store. It’s probably why unstructured, loosely fitted, and/or stretch knit garments are so common nowadays. (That, and it’s easier to wash them. And easier to make them cheaply in sweatshops. I want to punch the fast fashion industry in the face, but I digress.)

People have always come in a huge variety of shapes, all throughout history, but up until whenever mass production became the norm (late 19th and early 20th century I think? It happened gradually.) they had the advantage of having their clothes made specifically to fit them. Unless they could only afford secondhand clothes, but even then they’d probably alter them to fit.

And trans people existed back then too, and people cross dressed for various reasons. “Breeches roles” for actresses were hugely common in theatre, so I think it’s safe to say that breeches can be made to go over wide hips just fine.

I haven’t seen any of your pattern attempts and I don’t know how many you’ve done, but I can say with some degree of confidence that you’re having trouble because it’s your first attempt at a rather difficult thing that takes some time and practice to get good at. We all start out by sewing and drafting horrible stuff! Do not despair! Pattern drafting is a wonderful skill to have, and after enough bad patterns you will get to good ones! It’s a whole entire human you’re putting fabric around, and it takes some practice to develop an eye for what shapes work best on you, and how to correct various fit issues.

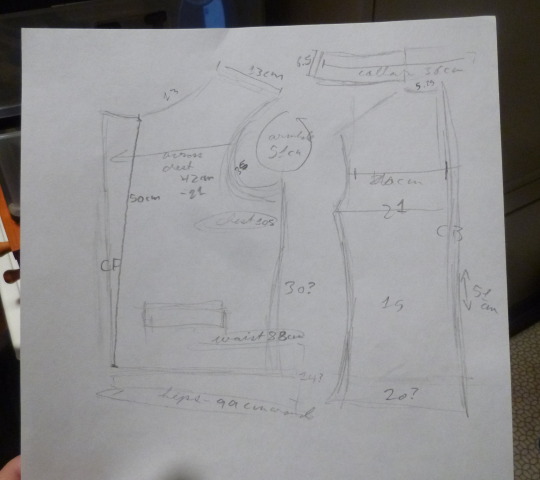

Here’s my pattern drafting method:

I usually use pattern diagrams from The Cut of Men’s Clothes, Costume Close Up, or the LACMA pattern project. All 3 of these sources have nice little scaled down diagrams of pieces traced from extant historical garments, and I start by tracing those onto a small sheet of printer paper. I get a reference picture or several of a similar garment. Preferably a portrait of someone wearing it, or the garment displayed well on a mannequin. I then stand in front of the biggest mirror in the house (wearing everything I’d be wearing under that garment) and imagine that garment on me, and where all the edges and seams are. I get my measuring tape and I measure various bits of the imaginary pattern pieces, and mark these measurements down on my little diagram. Here’s what the one for my yellow striped waistcoat looks like.

Once I’ve got a satisfactory amount of measurements marked down, I go to my big roll of stiff brown butcher paper and I draw out the pattern pieces full size according to these measurements. It’s ok if the measurements don’t all line up perfectly, because it’s awkward to measure yourself in front of a mirror, so they aren’t all exact.

The important thing is to get the lines nice and smooth, and approximately where they should be, and to get the overall shapes similar to the diagram pattern pieces in a way that fits your proportions. They won’t be exactly the same as the diagram in the book because nobody is shaped exactly the same as whoever wore the original garment. For the above waistcoat I had to flare the hips out waay more than on the inspiration pattern, but when it’s on me that’s not really noticeable because it fits. (Mostly. I still need to work on the shoulders..) I then mock it up in crappy thrift store fabric or old bedsheets, and the past few times I’ve done patterns this way I’ve found them to fit surprisingly well, needing only a few small alterations. I’m very visual, so this method works for me, but other people may prefer different methods.

In college we learned to draft modern patterns with math formulas, but I don’t like doing that, and the basic blocks we did then aren’t super helpful for historical cuts anyways. I know that for the 19th and 20th centuries there are lots and lots of tailoring books available that have drafting instructions, but as I have not yet dipped my toes into the 19th century I can’t really comment on them.

However you’re drafting, be sure to look at lots and lots and lots of reference pictures from the era so that you get a good picture in your head of what the fit and cut is supposed to be like. Things fit differently in different eras. For example, 18th century coat sleeves are cut much tighter than modern ones, and with a considerably smaller armhole. (Which actually gives you a far better range of motion.) They don’t have any shoulder padding either. And 18th century breeches have wrinkles at the crotch, it’s just part of how they fit.

Alright, I think that’s all I’ve got to say on patterning for now. And now to address the question of androgynous silhouettes! I really don’t want to fall into the trap of equating “androgynous” with “masculine”, but most of the things that immediately come to mind are historical menswear because they’ve got drastically different silhouettes that don’t read as very masculine to the average modern onlooker. One of the things that made me start on a 1730′s project was the early 18th century silhouette. (That, and the lure of Huge Coat Cuffs) Just look at those adorably poofy coat skirts!

Antoine Hérisset, 1729, Rijksmuseum.

The early-to-mid 19th century is another great period for men’s silhouettes. Tiny waists and softly rounded chests (you see padding in a lot of the waistcoats) were in, and the men in the fashion plates are drawn with doll faces, dainty little feet, and pretty substantial hips. Behold:

(1834) I’d like to do an 1830′s outfit someday, and to make a pair of mens stays for it.

Here’s another one so you can see The Hips. The darn source link isn’t working, but this is from Costume Parisien, 1823.

Young man’s cotton summer jacket, c. late 1840′s.

Depending on how concerned you are about foolish comments from random strangers, there’s also the second half of the 17th century to consider. What could be more androgynous than a vaguely human shaped wad of fabric and frills?

I Cannot find the source for this but it’s a French engraving c. 1660.

Now, I am less educated on historical women’s fashion, but I know that those shapeless little 1920′s dresses were going for a more androgynous look. Flat chests and short hair for girls was fashionable, and you can see the beginnings of that boxier silhouette in the 1910′s.

1910′s women’s suits are magnificent.

Walking suit, c. 1912, V&A.

And riding habits! From the 17th to the 19th century (and maybe beyond, I don’t know) women’s riding habits had the same style lines as mens suits, but were made with the silhouette of a dress, and it looks very sharp. (Especially the 18th century ones, but I’m biased.) They usually consist of a jacket and matching skirt.

Wow that is a much longer answer than I expected to write. I must make an FAQ page so people can find these more easily.

I hope this was helpful, and I wish you all possible success in future pattern drafting endeavours!

493 notes

·

View notes

Note

The perfect Amoureux Christmas day!! Post reunion with their little Prince ~T

I couldn’t figure out how to end this for way too long but I think I finally got it how I wanted it!

I also realized that the Christmas Tree wasn’t introduced to British culture until 1840 by real life Prince Albert but I guess this will just be another twist of history in this separate universe!

December 25, 1822

At fourteen-months-old, Henry, Prince of York, was already starting to show signs of his father’s cheeky personality. This was only apparent at his young age through his sudden awareness of how to sneak out of his crib, meaning the guards at Kensington Palace were suddenly attuned to a toddler dressed in white nightclothes rushing past them down the hallway.

Jack and Zach, who had been doing their usual early morning rounds of the palace, exchanged wide-eyed glances as the tiny prince went wobbling right past them.

“Your Royal Highness!” Jack called quietly first, rushing after the small boy, Zach right behind him. It didn’t take much effort to catch up to the toddler and Jack picked him up by his armpits, making the small boy giggle. “You must stay in your bedchamber, sir.”

“I will return him.” Zach offered, scooping up the tiny toddler in his arms. Henry only shrieked with laughter, the sound echoing down the hallway and nudging Louisa awake.

Her shifting had Daniel waking beside her and he pulled her close under the soft sheets to press a kiss to her head. Louisa smiled sleepily and cuddled into him some more, neither aware of their son’s escape from the room beside theirs until there was a knock at the door.

“Come in.” Daniel answered through a yawn, not even opening his eyes.

The door opened and Zach came in with their son, offering them a quick bow, “Your Royal Highnesses, good morning. Nothing to be alarmed about but Prince Henry seems to have escaped his bedchamber.”

“Oh my.” Louisa sat up quickly and held her arms out. “Bring him here please, Zach, thank you.”

Zach rushed over and set the giggling toddler on the bed before heading for the door to leave them be.

“Happy Christmas, Zach.” Louisa called after him.

He turned back to her with a bashful smile and bowed once more before leaving, “Happy Christmas, Miss.”

Louisa looked down at her son and his cheesy grin as he fell backwards onto the fluffy mattress, tangled up in his nightclothes, “Oh, Henry Alexander, what are we going to do with you, my sweet boy? Escaping on Christmas morning, hm?”

Henry only laughed as she leaned down to pepper kisses over his chubby cheeks and her fingers tickled his sides.

Daniel reached down to grab onto his son’s leg and tugged him farther up the bed to pull him into a tight embrace, the little boy smiling into his father’s chest for only a moment before trying to wiggle back out.

“Do you want your presents, mon coeur?” Louisa pet her hand over her son’s thin brown hair and leaned down to press a kiss to his head.

“You’ve never had Christmas presents before!” Daniel cooed, watching as Henry wrapped his little hand around his one finger and smiled up at Louisa, tiny dimples pressing into his cheeks and his eyes scrunched closed with glee.

“Is that a yes?” Louisa smiled at her son. Henry only shrieked with excitement, making his young parents grin at him.

Daniel scooted his son closer again so he could lean up just enough to press a kiss to his cheek, “What a handsome little prince.”

“I know.” Louisa gushed, her smile almost permanent on her face as she looked on adoringly at her son and her husband and how Henry patted his little hand against Daniel’s cheek, both of them staring at each other with the same light blue eyes and long lashes.

A butler came in with chipper good mornings and Christmas wishes as he opened their curtains for them and a few more staff came to help them get dressed and ready for the day’s festivities. One of the palace nannies came to take Henry to get dressed but Louisa insisted on doing it herself – much to the surprise of the staff. She had raised him nearly a year without help from any sort of staff and so she refused to go back on that once they returned to England. The staff at Highgrove knew their routines well but at Kensington, where they were staying for the holidays, some reminders needed to be said.

So Henry was sat on the bed after it was freshened up by one of the maids, kept busy with a toy, while Louisa and Daniel were helped into their Christmas clothes and had their hair tidied. Once they were ready, Louisa changed the baby and got him dressed herself into his own little Christmas outfit, and soon they were headed downstairs together, Henry perched on Daniel’s hip.

The whole British Royal Family were gathered in the dining room for breakfast and they ate together over a plentiful spread and good conversation. Presents were then opened in the sitting room in front of the large tree that was lit with candles and decorated in expensive ornaments and Henry plopped himself right down in front of it to reach from one of the wrapped gifts with little hands.

It was only proper to, in company of the King and Queen, to follow the strict rules that came with being a member of the Royal Family, but Louisa and Daniel instead got right down on the floor with their son. Christian and Anna eyed their brother and then their father, as if waiting for someone to call him out on his improper behaviour but the King only silently waved away the action in light of his grandson’s first real Christmas. So Anna eagerly dropped to the ground and Christian grabbed Cora’s hand and pulled her to the ground as well, joining their littlest family member by the Christmas tree as he opened up his first gift.

His little shriek with glee had Louisa grinning, petting her hand over his head as he hugged the soft doll to his chest. Henry turned to his other side where Christian and Cora were and held out his new toy to his uncle with his same dimpled grin.

“How lovely!” Christian cooed to his nephew, “What a lucky boy you are.”

“It’s so cute!” Anna squealed, taking the doll from the toddler to look at.

Daniel set his arm around Louisa’s back, being cautious not to accidently rip her gown that was billowing around her and across the wooden floors. She only shuffled closer to him and rested her head on his shoulder as they watched their little one get to his feet – using Christian’s leg as a crutch – and then wobbled back over to the tree, now distracted by the sparkly things that covered the branches and he reached for one with a gentle hand.

“Careful, now.” Daniel warned, gently pulling his son back from the tree.

“Pretty.” Henry whispered, trying to wiggle out of his father’s grasp and get back to the decorations.

“Yes, very pretty.”

“Oui.” Henry breathed.

“Oh, oui! My sweet French prince!” Louisa gasped through a grin, squishing her son’s cheeks to give him plentiful kisses from his spot on Daniel’s lap. Henry giggled loudly, trying to push his mother’s face away from him.

The gift giving continued, the King and Queen each opening a few from each other and from their three children. When Anna was opening her first diamond necklace and everyone was distracted, Daniel linked his finger around the neckline of Louisa’s dress to get her attention. When she looked over at him, he gestured to the table next to her that held a small array of pastries and she passed him his favourite without even needing to be asked. Instead of eating it himself, Daniel held it in front of his son on his lap, the toddler eyeing the chocolate truffle curiously before opening his mouth to be fed the dessert.

Henry’s little face easily moulded into a cheeky grin and his little fingers grabbed onto the edge of Daniel’s sleeve to pull his hand back down to him to take another bite. Louisa and Daniel laughed lightly as their son obviously inherited their shared love of desserts and he smiled up at them with chocolate smeared all over his mouth.

“Oh my.” the Queen laughed as everyone looked over at the little boy. “With all that chocolate he looks just like you when you were a baby, dear Daniel.”

“More.” Henry turned a little on Daniel’s lap to look up at him and he held out a tiny hand out, palm up, “Please, Dada.”

“This one is much better mannered however.” Christian teased.

Daniel shot an unimpressed glare at his brother as Louisa passed over another truffle to feed their grinning son and shared a soft kiss with her husband, resting her head on Daniel’s shoulder as Anna passed the toddler another present from under the tree. They sat with their small son as he opened his second present, chocolate smeared over his lips and his little fingers, his wide dimpled smile only warming up the room that much more as if he could do no wrong. Their perfect little prince; destined for greatness.

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

After your most recent post, I find myself very curious to know which era you dress the most like. I mean, I know you're a Crimson Peak fanatic (note: just joking) so either late 1870s or turn-of-the-century, but which???

Also, could you show us (re: me) a picture of your latest creation?! It would be greatly valued and appreciated

No no, I definitely am a Crimson Peak fanatic. I wear my obsession with pride at this point.

It's actually somewhat broader: late 1860s to early 1880s. Elliptical Hoop, First Bustle, and Natural Form, to be a bit more specific. Historically (hah) early 1870s/First Bustle has been my absolute favorite, but I've been inspired by my descent into CPeak madness- and my increasing attempts to Victorianize my wardrobe in a practical fashion for daily life without going 1890s, which is fine but decidedly not my favorite -to look more into Natural Form. Tragically I cannot wear a giant trailing bustle skirt on the subway at rush hour. Woe and Lamentation.

My latest creation isn't actually for me! It's this 1840s ball gown for my doll Maryse:

Not a great picture, but I’m answering this as I get ready for work. Sorry!

It’s part of an ensemble I’m making for her based on the folk song “Fair Charlotte, or A Corpse Going To A Ball.” The skirt is beaded with aurora borealis crystals at the hem and pearlescent white glass beads in frost patterns, as you can hopefully tell. There are also some nail art snowflakes stitched on, which was a huge pain in the ass.

She’ll eventually have a styled wig to match, slippers and stockings, and possibly Charlotte’s mantle and “silken scarf” from the song.

The artist who made her, Marina Bychkova, is known for drawing inspiration from history, literature, and fairytales, especially darker stories. So I felt like this would be the perfect theme for her first real outfit!

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

David Thacker's Adaptation of ‘A Doll’s House’

David Thacker and Realism

David Thacker’s 1992 television production of Henrik Ibsen’s ‘A Doll’s House’ replicates the theatrical naturalism that is evident in Ibsen’s original version, and uses realism to portray the life of a marginalised and oppressed member of society.

Realism is shown through Thacker’s use of authentic period furniture, specifically the cast iron stoves that appear in a corner in the hallway (Figure 1) and in the living-room (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Libre, K. (2019).

Figure 2.

These stoves are specific to 19th century Norway, and so have intentionally been used by Thacker to indicate the setting and the time period that this adaptation is set in. However, the purpose of these stoves is purely decorative, as when Nora goes to make up the fire in the stove, she goes to this one (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The position of this stove and the accompanying furniture is a part of the staging included in the original version by Ibsen, and so suggests that the others were included purely for historical context, and as part of the director’s own interpretation. This attention to detail by Thacker reinforces the realistic ideals that were prevalent at the time Ibsen wrote this play, as realism was utilised to create drama that was authentic, and that created the effect of the audience looking into their own homes to make them feel part of what they were watching, thus allowing them to see the inequalities and social issues within their own lives.

Costume

The costume choices for this adaptation reflect the clothes that would have been worn within this bourgeoisie society, as the dresses that were fashionable in the 1870s are described as having an “[…] elongated and tight bodice and a flat fronted skirt”, with “Low, square necklines […]” Victoria and Albert Museum (2016).

Figure 4.

Figure 5.

In Figures 4 and 5 above, you can clearly see both the tight-fitting bodice, and the low-cut, square neckline on Nora’s dress.

Figure 6.

What is also significant about this dress is its colour, as it’s the exact same shade of green as Torvald’s jacket (Figure 6) that we see right at the very beginning of Act 1. This costume choice foreshadows the ending of the adaptation with Nora’s speech, when she says, “You arranged everything according to your taste, and so it became my taste too […]” (A Doll’s House, 1992, 2:00:38-2:00:41). These ‘shared’ tastes are indicated through the matching colours of their outfits, and has been used by Thacker to reinforce Ibsen’s original idea that Nora is a character who has been controlled and moulded into the type of person that the men in her life have wanted her to be, thereby reflecting the 19th century social issues of gender inequality.

Figure 7.

Torvald’s costume (Figure 7) is also exceptionally accurate, specifically with his jacket, which is “[…] thigh length […]” and “[…] buttoned high on the chest” Victoria and Albert Museum (2016).

Original Staging

When ‘A Doll’s House’ was originally performed it would have used a stage with a proscenium arch. This created the effect of a photo frame that literally ‘framed’ the action, and made it so that the audience were looking inside this fictional house with its missing fourth wall, much like the fourth wall would be missing in an actual doll’s house. This created the effect of the characters being the audience’s dolls that they’d watch being moved about and ‘played’ with, in order to portray Ibsen’s desired effect.

Thacker’s adaptation means this type of stage is unable to be used, as it’s not being performed in a theatre. Instead, camera angles that allow the audience to feel like they’re following the characters through the house have been used, which still creates this feeling of being immersed in the drama, as seen here: https://www.youtubetrimmer.com/view/?v=ZJDnHQT2BDk&start=1667&end=1672

Single-Scene Analysis

The scene in Act 3 where Torvald reads the letter and everything that Nora has hidden from him comes to light, is one that handles the themes of conflict and identity. When he starts shouting for Nora and calls her a “miserable wretch” (1:49:30-1:49:31), the conflict begins, and we also see Torvald’s true identity during this scene.

While he’s shouting at Nora, we see how insensitive he is to her feelings, as well as how self-centred he is, especially when he says “[…] you’ve completely destroyed my happiness. You have ruined my whole future for me” (1:50:26-1:50:34). In this moment, we see how truly heartless Torvald is; he doesn’t even give her the opportunity to explain that she got herself into debt out of her love for him, and now, when she needs her husband’s support more than ever—as she knows she could be arrested for this—he completely disregards how she’s feeling about this, and instead starts panicking about what’s going to happen to him, and his future.

Figure 8.

This still (Figure 8) from the scene shows the Christmas tree in the background next to Torvald, and is symbolic of things coming to an end; Christmas day has passed, and the tree is dying, and now that Nora’s secret is out, her life of deception and of being controlled by Torvald is now also coming to an end.