#Augusta Library

Photo

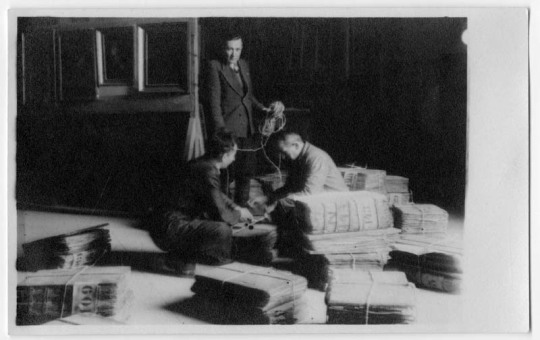

I materiali di pregio della biblioteca Augusta vengono trasferiti a Montelabate sotto la supervisione del direttore Cecchini per tutelarli durante il periodo bellico (Valuable materials from the Augusta Library are moved to Montelabate under the supervision of Director Cecchini to protect them during the war period), Perugia, Italy, 1940-1945.

#Vintage#Retro#Library#Libraries#Biblioteca#Biblioteche#Perugia#Italia#Italy#1940#1940s#40s#1945#Book#Books#Bookish#Libro#Libri#biblioteca Augusta#Montelabate#Augusta Library#War#War Period#Photography#Black and White

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Milestone Monday

The King's Hares, from Norway

The Princess with the Twelve Pair of Golden Shoes, from Denmark

Queen Crane, from Sweden

The Rooster, the Hand Mill and the Swarm of Hornets, from Sweden

Ti-Tirit-Ti, from Italy

The Adventures of Bona and Nello, from Italy

The Hedgehog Who Became a Prince, from Poland

The Flight, from Poland

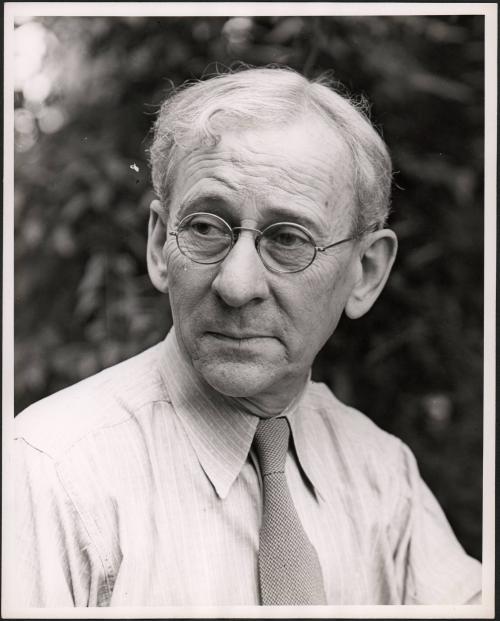

April 1st is the birthday of American librarian and storyteller Augusta Braxton Baker (1911-1998). Born to two schoolteachers in Baltimore, Baker was a voracious student who read at a young age and careened through elementary and high school. With advocacy support from Eleanor Roosevelt, Baker was admitted to the Albany Teacher’s College and in 1934 earned a B. A. in Education and a B. S. in Library Science making her the first African American to earn a librarianship degree from the college.

In 1939, Baker went on to work as the children’s librarian at New York Public Library’s Harlem branch, founding the James Weldon Johnson Memorial Collection of Children’s Books to showcase representation of Black children and life in books, and beginning a lifelong career with children’s literature and the New York Public Library (NYPL). In 1953, she was appointed Storytelling Specialist and Assistant Coordinator of Children’s Services, quickly moving into the Coordinator of Children’s Services position years later and becoming the first African American to hold an administrative position with NYPL. Throughout her career, Baker was active with the American Library Association, and chaired committees for the Newbery Medal and Caldecott Medal recognizing excellence in children’s literature.

In celebration of Baker’s birthday, we’re sharing The Golden Lynx and Other Tales, a collection of international folk tales compiled by Baker and illustrated by Austrian artist Johannes Troyer (1902-1969). This is the first edition of the book published in 1960 by J. B. Lippincott and is signed by Baker, who writes in the introduction, “No story has been included in this collection that has not stood the supreme test of the children’s interest and approval”.

Read other Milestone Monday posts here!

View more posts on children's books here.

– Jenna, Special Collections Graduate Intern

#Augusta Braxton Baker#Milestone Monday#The Golden Lynx and Other Tales#Johannes Troyer#J.B. Lippincott#New York Public Library#American Library Association#Newberry Medal#Caldecott Medal#Historical Curriculum Collection#birthdays

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

"We are not prepared for her to be so brown," his mother said.

"Indeed," Lord Bute said, adding absolutely nothing to the conversation.

"And it doesn't come off."

At that, George's eyes snapped open. "What?"

"It doesn't come off," his mother repeated. "I rubbed her cheek to be sure."

"Good God, Mother," George said nearly rising from his chair. Reynolds jumped back , just fast enough to keep from slicing George's throat with the razor.

"Please tell you did not try to rub the skin off my intended bride," George said.

-Queen Charlotte(book)

#quotes#book quotes#literature#books & libraries#life quotes#relationship quotes#julia quinn#shonda rhimes#bridgerton#queen charlotte: a bridgerton story#queen charlotte book#princess augusta#lord bute#king george#young king george#spoilers

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Do you have what it takes to complete our Operation Supernova Escape Room? Put your skills to the test to see if you have what it takes!

Did you know that our branches are doing a Star Wars Reads takeover? Learn more about other SWR programs at your local library here: www.arcpls.org/swrd

3 notes

·

View notes

Video

n838_w1150 by Biodiversity Heritage Library

Via Flickr:

The gardener's assistant :. London ;Blackie & Son,1859.. biodiversitylibrary.org/page/57724435

#Gardening#Horticulture#U.S. Department of Agriculture#National Agricultural Library#bhl:page=57724435#dc:identifier=https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/57724435#Augusta Innes Withers#HerNaturalHistory#WomenInScience#flickr#phalaenopsis grandiflora#Correa cardinalis#Moth orchid#moon orchid#mariposa orchid#anggrek bulan#orchid#orchids#eastern correa#Correa reflexa#common correa#correa#native fuchsia#botanical illustration#scientific illustration

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

i told my mom about waiting for annihilation to become available at the library and she was like. just order it on amazon 🤪. ummm no heehee the library has his books i just need to wait multiple months for the augusta library to fork it over

#txt#i love that our coastal system got integrated with pines but like. it takes so long for our smaller libraries to get holds in#i think its crazy that savannah doesnt have his books. we gotta order them from augusta or atlanta

1 note

·

View note

Text

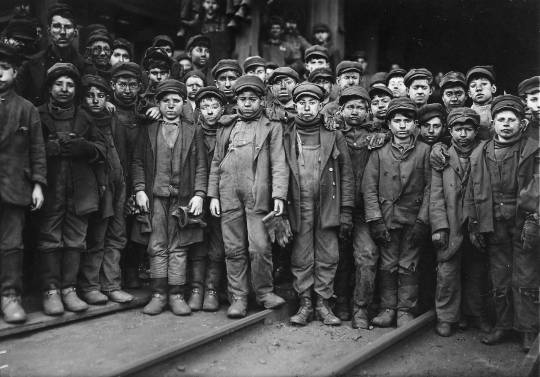

📷 Lewis Hine 📷

Lewis Hine - Newsies, 1910 - Newsies: Newsies at Skeeter's Branch, Jefferson near Franklin. They were all smoking. St. Louis, Missouri.

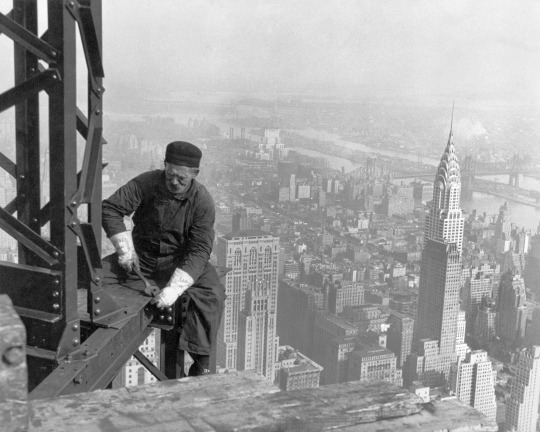

Lewis Hine, Photographer of the American Working Class

Few American photographers have captured the misery, dignity, and occasional bursts of solidarity within US working-class life as compellingly as Lewis Hine did in the early twentieth century.

Lewis Hine - Breaker boys, 1910 - Child workers who broke down coal at a mine in South Pittston, Pennsylvania.

Lewis Hine - Little Spinner 1909, Globe Cotton Mill. Overseer said she was regularly employed. Augusta, Georgia. Library of Congress

Lewis Hine - Ten Year Old Spinner, North Carolina Cotton Mill, 1908

Lewis Hine - Little Lottie 1911. She was a regular oyster shucker in Alabama Canning Co. (Bayou La Batre, Alabama)

Lewis Hine -Little Rosie 1913. She was a regular oyster shucker. She was just 7 years old and in her second year at Varn & Platt Canning Co. Bluffton, South Carolina

As an investigative photographer, Hine chronicled the normalized labor abuses in US factories leading up to the Great Depression. Not only did he help introduce some of the country’s first child labor laws, he also revolutionized photography’s artistic use value.

Lewis Hine - Child laborers in glasswork. Indiana, 1908

Lewis Hine -Baseball team composed mostly of child laborers from a glassmaking factory. Indiana, 1908

Lewis Hine - Factory Boy, Glassworks, Alexandria, Virginia, 1909

Lewis Hine - One Of The Loading Boys In J. S. Farrand Packing Co. Baltimore, Maryland, 1909

Lewis Hine - Newsboys, Bridgeport Conn., 1909

Hine once argued that a good picture is “a reproduction of impressions made upon the photographer which he desires to repeat to others.” For him, an organized workforce was the epitome of empathy and mutual benefit, which he hoped to convey to the greater American public.

Lewis Hine - Empire State Building worker in 1931

Lewis Hine - Power house mechanic working on steam pump, 1920.

Lewis Wickes Hine

(1874-1940)

“If I could tell the story in words, I wouldn’t need to lug around a camera.” -Lewis Hine

#photography#vintage photography#lewis hine#historical photos#child labor#labor laws#investigative photographer

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

Playing Dress Match-up: a painted dress and the actual dress or a close match.

Albert Braïtou-Sala (Spanish, 1885-1972) • Portrait of Marthe Chenal • 1921 • National Library of France Opera Museum

Isn't Marthe grand? And, of course, very rich. I could not find a dress that to my estimate was a good match. That bias cut bodice made from what looks like metallic silk, with a flowy but curve flattering skirt of perhaps crepe? It slightly gathers at the waist, falling to the ankles with a subtle, elegant train in back. Really gorgeous. In my search there were many more dresses of the 1930s that fit this profile. The one below, for example. It was worn by the American businesswoman and socialite, Marjorie Merriweather Post.I posted about her portrait here.

Evening Dress • American • c. 1933 • Cream silk crêpe, cream organza

In 1921, the flapper trend was only beginning to take shape. Waists had dropped a bit and would continue into the decade to drop further.

Fashion changes from 1924-1925

Although I didn't find a dress I liked as a match-up to the portrait of Marthe Chenal, I did find an evening coat that resembles the one she's so brilliantly flaunting.

Velvet opera coat • 1915-1920 • Augusta Auctions

#art#portrait#painting#fashion history#art history#albert braïtou-sala#1920s fashion#1930s fashion#spanish artist#the resplendent outfit blog#margerie merriweather post#historical fashion#fine art#fashion timeline#female portrait#fashion blogs on tumblr

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

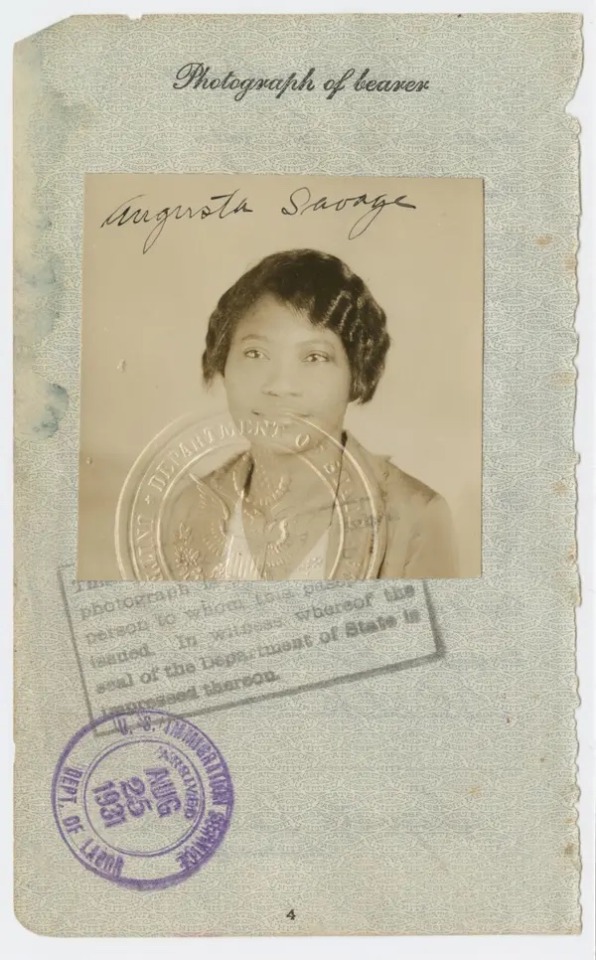

The 1931 passport photograph of the sculptor Augusta Savage.

Credit: Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, the New York Public Library

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

USS HOUSTON (CA-30) and USS AUGUSTA (CA-31) on the Wusong river (Suzhou Creek) in Shanghai, China. Photographed during the Sino-Japanese Hostilities.

Date: February 1932

University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee Library: pe000035, fr208399, pe001214, fr202530

#USS HOUSTON (CA-30)#USS HOUSTON#USS AUGUSTA (CA-30)#USS AUGUSTA#Northampton Class#Cruiser#Warship#Ship#United States Navy#U.S. Navy#US Navy#USN#Navy#Shanghai#China#Sino-Japanese Hostilities#February#1932#interwar period#my post

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Black Woman Artist Who Crafted a Life She Was Told She Couldn’t Have

The sculptor Augusta Savage at work in her studio in Harlem.

At the dawn of the Harlem Renaissance, Augusta Savage fought racism to earn acclaim as a sculptor, showing her work alongside de Kooning and Dalí. But the path she forged is also her legacy.

By Concepción de León

Published March 30, 2021

In 1937, the sculptor Augusta Savage was commissioned to create a sculpture that would appear at the 1939 New York World’s Fair in Queens, N.Y. Savage was one of only four women, and the only Black artist, to receive a commission for the fair. In her studio in Harlem, she created “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” a 16-foot sculpture cast in plaster and inspired by the song of the same name — often called the Black national anthem — written by her friend, James Weldon Johnson, who had died in 1938.

The sculpture was renamed “The Harp” by World’s Fair organizers and exhibited alongside work by renowned artists from around the world, including Willem de Kooning and Salvador Dalí. Press reports detail how well the piece was received by visitors, and it’s been speculated that it was among the most photographed sculptures at the Fair.

But when the World’s Fair ended, Savage could not afford to cast “The Harp” in bronze, or even pay for the plaster version to be shipped or stored, so her monumental work, like many temporary works on display at the Fair, was destroyed.

The story of the commission and destruction of “The Harp” and its eventual fate is a microcosm of the challenges Savage faced — and the ones Black artists dealt with at the time and are still dealing with today. Savage was an important artist held back not by talent but by financial limitations and sociocultural barriers. Most of Savage’s work has been lost or destroyed but today, a century after she arrived in New York City at the height of the Harlem Renaissance, her work, and her plight, still resonate.

Augusta Savage at work on the sculpture that would become known as “The Harp.” Credit... via The New York Public Library

“Disagreeable complications”

Savage, born Augusta Christine Fells in Green Cove Springs, Fla., in 1892, was the seventh of 14 children. She started making animal sculptures from clay as a child, but her father strongly opposed her interest in art. Savage once said that he “almost whipped all the art out of me,” according to the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Savage arrived in Harlem a century ago in 1921 in the early years of the Harlem Renaissance. She was nearly 30; had already been twice married, widowed and divorced; and had a teenage child, Irene, whom she left in the care of her parents in Florida. She applied and was accepted to the Cooper Union art school, and completed the four-year program in three years. She took the surname Savage from her second husband, whom she divorced. In 1923, she married Robert L. Poston, her third and final husband. Poston died a year later.

The year she married Poston, Savage was one of 100 women awarded a scholarship to attend the Fontainebleau School of Fine Arts in Paris. But when the admissions committee realized that it had selected a Black woman, Savage’s scholarship was rescinded.

In a letter explaining the decision, the chairman of Fontainebleau’s sculpture department, Ernest Peixotto, expressed concern that “disagreeable complications” would arise between Savage and the students “from the Southern states.”

Savage did not accept the rejection quietly. “She used the Black press to make the limits that she was facing known to the larger national and international public,” Bridget R. Cooks, an art historian and associate professor at University of California, Irvine, said. “She had a real determination and sense of her own talent and a refusal to be denied.”

In the years after the Fontainebleau episode, Savage was commissioned to create busts for prominent African-American figures such as the sociologist and scholar W.E.B. Du Bois and the Jamaican activist Marcus Garvey. She also created “Gamin,” a painted plaster bust portrait based on her nephew that became one of her most well-known pieces, praised for its expressiveness. (It was later cast in bronze.)

“Gamin” earned her a Julius Rosenwald fellowship in 1929 to travel to Paris, which had become a refuge for Black artists, including the painter Palmer Hayden and the sculptor Nancy Elizabeth Prophet. Savage studied at the Académie de la Grand Chaumière and had works displayed at the Grand Palais and other prominent venues.

When she returned to Harlem in 1932, she opened the Savage Studio of Arts and Crafts, where she taught prominent artists such as Jacob Lawrence, Gwendolyn Knight, Norman Lewis and Kenneth B. Clark. Clark later turned to social psychology and developed, with his wife Mamie, experiments using dolls to show how segregation affected Black children’s self-perception.

The community-driven education that Savage championed is part of the African-American tradition, Dr. Cooks said, because Black people have historically been excluded from formal academic spaces. “But for her to open her own school is something entirely different,” Dr. Cooks added. “That is becoming a business person. That’s taking on a leadership role for which she doesn’t have any models in terms of Black people in the art world and Black women in particular. ”

In 1934, Savage became the first African-American member of the National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors (now the National Association of Women Artists). In 1937, she worked with the W.P.A. Federal Art Project to establish the Harlem Community Art Center and became its first director. Eleanor Roosevelt, who attended its inauguration, was so impressed with the center that she used it as a model for other arts centers across the country.

Gwendolyn Bennett, Sara West, Louise Jefferson, Augusta Savage and Eleanor Roosevelt in 1937. Credit... The New York Public Library/Schomburg Center

“She created a pathway for careers for Black artists,” Tammi Lawson, the curator of the art and artifacts division of the Schomburg Center, which has the largest holding of Savage’s work, said. “She taught them, she gave them the tools, and she got them work.”

Sandra Jackson-Dumont, the director and chief executive officer of the Lucas Museum of Narrative Art in Los Angeles, agrees. “She, for me, represents someone who believed that she wasn’t compromising her studio practice or who she was by teaching and bringing people along,” said Ms. Jackson-Dumont, adding that Savage understood “how to use the system’s resources to catalyze folks.”

Yet the later years of Savage’s artistic career were marked by adversity. After taking a hiatus to work on her sculpture for the World’s Fair, Savage returned to the Harlem Community Art Center to find that her job had been filled. She briefly tried to establish the Salon of Contemporary Negro Art in Harlem in 1939, but the gallery lasted only three months.

“Joe Gould’s Teeth,” a 2016 book by the historian Jill Lepore, revealed archival evidence that Gould, an eccentric writer, had harassed Savage by calling her incessantly, insulting her, following her to parties and telling people she had agreed to marry him. In the early 1940s, Savage abruptly left her home in Harlem for a farmhouse in Saugerties, N.Y., in the Catskill Mountains, where she continued to make busts and teach local children. In Harlem, the community art center she had founded was closed in 1942 when federal funds were cut during World War II.

Savage remained in Saugerties until Gould died in 1957 and she only later returned to Harlem. She died in relative obscurity in March 1962 of cancer, at 70.

“A blueprint for what it means to be an artist that centers on humanity”

Jeffreen Hayes, who is now a curator and the executive director of Threewalls, an arts nonprofit in Chicago, was a graduate student at Howard University when she learned about Augusta Savage’s work. A professor mentioned the sculptor in passing during a section on the Harlem Renaissance.

“I remember my professor showing slides of Augusta Savage,” Dr. Hayes said, “and then we just kind of moved on.”

Dr. Hayes, though, was struck by this story of a resilient Black woman whose greatest works have been lost but who made a life as an artist, teacher, arts center director and community organizer against the backdrop of Jim Crow laws and the Great Depression.

“I don’t think about Augusta Savage as someone who only made objects,” Dr. Hayes said, but rather as someone who “has really left behind a blueprint of what it means to be an artist that centers humanity.”

In 2018, Dr. Hayes curated the exhibition “Augusta Savage: Renaissance Woman” at the Cummer Museum in Jacksonville, Fla., which aimed, according to the catalog, to “reassess Harlem Renaissance artist Augusta Savage’s contributions to art and cultural history in light of 21st-century attention to the concept of the artist-activist.”

“Savage’s artistic skill was widely acclaimed nationally and internationally during her lifetime,” the catalog reads, “and a further examination of her artistic legacy is long overdue.”

At a moment when discourse has centered on the artistic and political role of public art and monuments, the continuing absence of a work like “The Harp” becomes even more acute.

After the Civil War, as cities evolved in the 19th and 20th centuries, sculptors formed close alliances with architects, such that parks, town squares and other public spaces were designed with sculptures in mind. Unlike paintings, which are typically housed in museums, sculptures and monuments hold an outsized symbolic value because of their presence in public life.

“Your public art should align with a community’s values,” said James Grossman, the executive director of the American Historical Association. “Every generation, each state should step back and say, maybe it’s time for somebody else” to be honored.

Savage with her sculpture “Realization” in 1938. Credit... Andrew Herman, via The New York Public Library/Schomburg Center

In assessing “Augusta Savage: Renaissance Woman,” the Times art critic Roberta Smith noted of another Savage sculpture titled “Realization”: “It never made it beyond its forcefully modeled nearly life-size clay version. It’s heartbreaking to think the difference its survival might have made.”

Recently, in the context of questions over Confederate monuments, there have been calls to recreate Savage’s “The Harp” and display it at the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington.

Savage viewed her own legacy with humility, putting the emphasis on the success of her students. In a 1935 interview in Metropolitan Magazine, she said, “I have created nothing really beautiful, really lasting, but if I can inspire one of these youngsters to develop the talent I know they possess, then my monument will be in their work.”

Dr. Cooks said she “would disagree” with Savage’s assessment of her own work; “I think everybody would,” she added. For Dr. Cooks, it’s clear that Savage saw her legacy as “someone who could set up opportunities for other people who were younger than her, to have the space to build a Black infrastructure, essentially, so they could succeed.”

In this sense, Savage’s legacy lies as much in the life she built for herself as in the work she made for the world, as evidenced in surviving film of Savage guiding students or creating sculpture in her studio.

In her work at Threewalls, Dr. Hayes said she aims to honor Savage’s mission: to “build a larger ecology that intentionally builds a relationship with community,” as Dr. Hayes put it.

Dr. Hayes didn’t have the support of people like Savage to guide her in the art world early on. “I feel really good that I can pass on that wisdom to the next generation coming up,” she said.

A correction was made on:

March 31, 2021

An earlier version of this article misstated the surname of the director and chief executive officer of the Lucas Museum of Narrative Art in Los Angeles. She is Sandra Jackson-Dumont, not Dumont-Jackson.

A correction was made on

April 5, 2021

An earlier version of this article misstated the year of Joe Gould's death. He died in 1957, not 1954.

When we learn of a mistake, we acknowledge it with a correction. If you spot an error, please let us know at [email protected].

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I materiali di pregio della biblioteca Augusta vengono trasferiti a Montelabate sotto la supervisione del direttore Cecchini per tutelarli durante il periodo bellico (Valuable materials from the Augusta Library are moved to Montelabate under the supervision of Director Cecchini to protect them during the war period), Perugia, Italy, 1940-1945.

#vintage#retro#library#libraries#bibliotecas#biblioteche#librarian#librarians#Italia#Italy#Perugia#1940#1945#1940s#40s#photography#black and white#war#war period#book#books#bookish#libro#libri#biblioteca Augusta#Augusta Library

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Further into the thirties (from top to bottom) -

The sleeves are usually elbow length and close, but not tightly squeezing, the arm and cuffed, An under-sleeve with a flared cuff emerges from the sleeve.1735 A Music Party by Marcellus Laroon (Birmingham Museums & Art Gallery - Birmingham, West Midlands, UK). From their Web site 1638X2246. No panniers here.

1735 Catherine Havers attributed to Barthélemy Du Pan (Temple Newsam House - Leeds, West Yorkshire, UK). From artuk.org 1414X1818. The dress could have been worn, minus the cuffs, until the 1770s.

1735 Catherine Hyde, Duchess of Queensberry, as a Dairy Maid, Marble Hill by Charles Jervas (Marble Hill House - Twickenham, London, UK). From artsandculture.google.com/entity/catherine-douglas-duchess-of-queensberry/m0gfdypy 1722X2138.

1735 Henrietta, née Godolphin, wife of Thomas Pelham-Holles, Duke of New Castle Upon Tyne and first Duke of Newcastle Under Tyne and Prime Minister by Charles Jervas (auctioned by Sotheby's) 920X1163.

1736 Anne, Princess Royal and Princess of Orange by Bernard Accama (location ?). From the lost gallery's photostream on flickr 1047X1539.

1736 Augusta of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg, Princess of Wales by Charles Philips (National Portrait Gallery - London, UK). From www.liveinternet.ru/users/marylai/post292168318 2400X2998.

1736 Johanna, Mrs Robert Warner of Bedhampton, and Her Daughter, Kitty (d.1772), Later Mrs Jervoise Clarke Jervoise by Joseph Highmore (Mottisfont Abbey - Mottisfont, near Romsey, Hampshire, UK). From bbc.co (now artuk.org) 651X800.

1736 Katherine Hall of Dunglass by Allan Ramsay (private collection). From the Philip Mould Historical Portraits Image Library; fixed spots w Pshop 2418X3023.

#1730s fashion#Georgian fashion#Louis XV fashion#Rococo fashion#Marcellus Laroon#train#shoes#Catherine Havers#Barthélemy Du Pan#lace engageantes#fur muff#Catherine Hyde#Charles Jervas#U neckline#Henrietta Godolphin#V neckline#modesty piece#Princess Royal Anne#Bernard Accama#robiings#Princess of Wales Augusta#Charles Philips#court mantua#Johanna Warner#Joseph Highmore#cap#square neckline#Katherine Hall of Dunglass#Allan Ramsay#long hair

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Come create works of art whether it is abstract artwork using the acrylic paint pouring technique, a drawing, or a painting to decorate the YA space. For every hour you create artwork, an hour of community service will be awarded. Call 706-434-2036 to register. Best for ages 12-18.

0 notes

Photo

Morgan and Marvin Smith (American, 1910-1993) (American, 1910-2003)

Marvin Painting a Self-Portrait

c. 1940

Gelatin silver print

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library Photograph

© Morgan and Marvin Smith / via: Art Blart

Morgan and Marvin Smith were identical African-American twin brothers. They were photographers and artists known for documenting the life of Harlem in the 1930s to 1950s. …

The Smiths decided to commit themselves to the media of photography in 1937 and took free art classes taught by sculptor Augusta Savage. There they met numerous other influential artists including Jacob Lawrence and Romare Bearden. Morgan became the first staff photographer for New York Amsterdam News in 1937, the most popular Black newspaper at the time. Two years later they opened their own photography studio, M & M Smith Studios, next to the famed Apollo Theater on 125th Street. The twins were the theatre’s official photographers and through this job met influential models, artists and performers. Their studio became a hub of activity for entertainers and writers, as well as the location of the majority of their portrait photography. They photographed George Washington Carver and Billie Holiday, among other famous Black artists and politicians, as well as street life in Harlem during this time.

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

Euphemia waltzes into her dorm, letting the door slam shut behind her. Minerva’s head snaps up from where she’s reading on her bed.

“Must you be so dramatic Euphemia?”

Effie winks at her before schooling her expression into something more serious. “There’s been another attack. Third year Ravenclaw girl.”

Minerva slams her book shut and sits up as Augusta gasps and drops her quill. The two of them move towards Effie.

“Which one? Where did it happen? Is she okay?” Minerva asks. Augusta takes one of Effie’s hands in her own and squeezes it gently.

“I just saw Potter outside the library and he stopped to tell me. It was the Eileen girl, you know her? She’s only petrified though.”

Augusta smirks. “So you’re on speaking terms with Potter again?”

Effie rolls her eyes. “Someone’s in the Hospital wing and all you got out of that is that I had one conversation with that twit?”

Minerva clicks her tongue at the pair of them. “You’re both degenerates.”

Effie shrugs, grinning. “You love us Minnie.”

#Minnie is James godmother pass it around#Minerva McGonagall#augusta longbottom#euphemia potter#the marauders

22 notes

·

View notes