#child ballads

Text

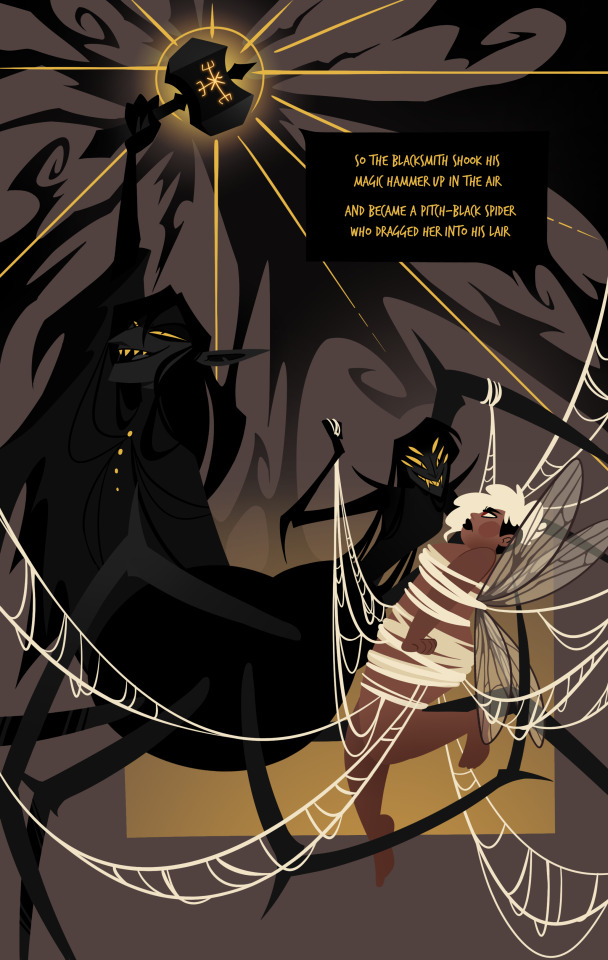

A redo of my old comic "The Two Magicians"

Read on Tapas: HERE

#the two magicians#comics#webcomic#child ballads#lgbtqplus#sapphic#wlw#lesbian#OC#fae folk#satorart#sator comics

462 notes

·

View notes

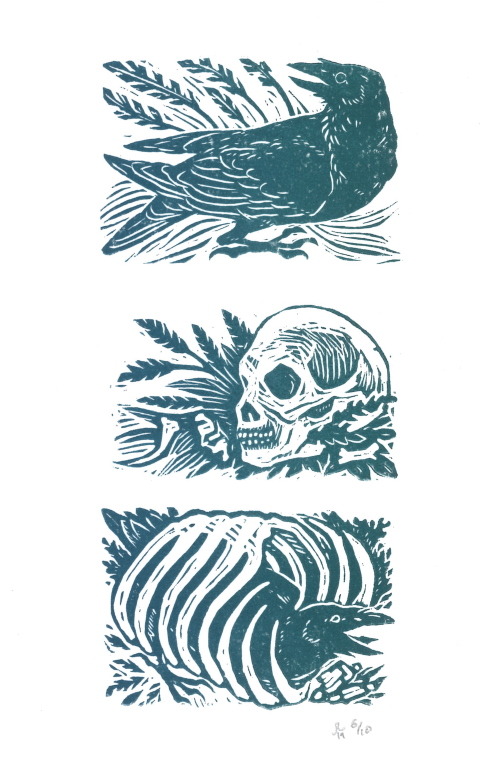

Text

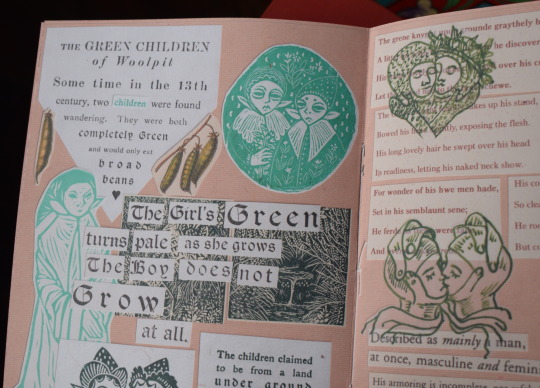

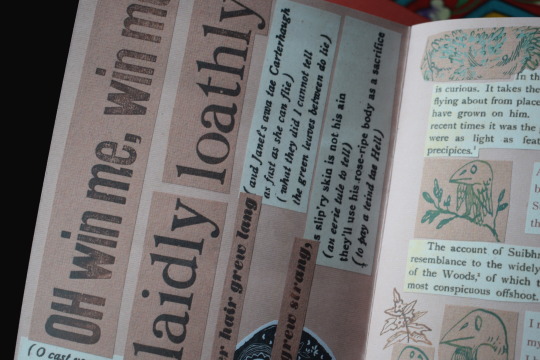

I had copies printed for this collage zine about Queer bodies, folklore, shape-shifting and monsters. RightVillainousCo on Etsy :)

#illustration#art#collage#folklore#queer art#history#ballads#mythology#monsters#child ballads#printmaking

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

like 90% of child ballads are about the universal sentiment of what if i DIED then you’d all be sorry >:(

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

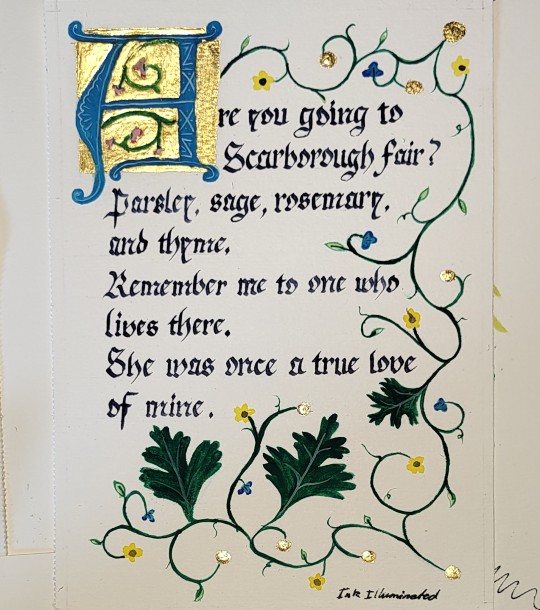

Fuck me gold leaf is a pain in the ass. We'll get there eventually and it'll be worth it for the shiny

The leaves were pretty fun to paint though I can't lie. Definitely need to incorporate more of those into my gothic work

#art#illumination#calligraphy#gothic#scarborough#Scarborough fair#the elfin knight#child ballads#simon and garfunkel

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Favorite Child Ballads Pt 1

The Child Ballads are a collection of 305 ballads from England and Scotland. They were anthologized by Francis James Child in the second half of the 19th century, but date back between 200 and 500 years.

Here's a couple of my favorites.

youtube

Hind Horn (Child Ballad 17), recorded by Maddy Prior

When young Hind Horn goes to sea, the King's daughter Jean gives him a magic ring, so he knows if he still has her heart. I always want to cheer at the climax of the song, when the lovers are reunited.

youtube

The Bonnie House of Airlie (Child Ballad 199), recorded by FullSet

The emnitiy between the Campbells and the Ogilvys boils over when Archibald Campbell raids Airlie Castle, the home of the James Ogilvy, Earl of Airlie, in the summer if 1640. There's roundheads vs cavaliers and a poignant heroine in Ogilvy's wife Lady Margaret.

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

And then he changed all in her arms

Into a wild bear

She held him tight and feared him not

He was her husband dear

Watercolour and ink pencil on paper, 2020.

He’s such a little bear lol I don’t think I checked human size comparisons when I drew this.

I painted this for drawtober in 2020 as a bit of respite from my fall kids series. I’ve loved Anaïs Mitchell and Jefferson Hamer’s renditions of the Child ballads for years, and Tam Lin is my favourite. Who doesn’t love a tale of passionate rebellion? I remember hearing it for the first time in the small chapel next to my first year uni dorms. The singer’s voice was so clear and bright, I think that particular singing of it will always stay with me. When I looked up the song later I realized I already knew Geordie from the same album because of some folk mix I liked on 8tracks

Anyway! I tried a lot of strange things with this piece texturally that I would not say were successful, also shame on me for not letting it dry properly and leaving the colour bleeds! But I like where I was going with the rose bushes and if I had gone harder into the pared-down pattern-as-texture I think it would have been quite cool.

#illustration#artists on tumblr#traditional art#pencil crayon#watercolor#watercolour#tam lin#child ballads#anais mitchell#anaïs mitchell#tamlin#bear

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“They will turn me in your arms into a wild wolf,

but hold me tight and fear me not, I am your own true love,”

The ballad of Tam Lin (Child 39) is one of my all time favorite songs/folk stories. I find it to be such a fascinating glimpse at how stories change over such long periods of time. This piece was mostly inspired by the Anaïs Mitchell cover, but I also am quite fond of the Fairport Convention version as well.

#tam lin#anais mitchell#fairport convention#child ballads#the ballad of tam lin#drawing#art#fantasy#fairy tales#folk tales#scottish folklore#irish folklore#faeries#halloween#samhain#celtic art

167 notes

·

View notes

Text

So Janet tied her kirtle green,

a bit above her knee,

And she's gone to Carterhaugh,

as fast as go can she.

Oh, tell to me, Tam Lin, she said,

why came you here to dwell?

The Queen of Fairies caught me,

when from my horse I fell.

And at the end of seven years,

she pays a tithe to hell,

I so fair and full of flesh,

and fear it be myself.

Oil on board, 12”x16” in a secondhand, modified frame. Based on one of my favorite child ballads, Tam Lin.

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's Halloween, so please make sure you're practicing safe sacrificing! Pick a rose from forests where a mysterious faerie lives! Pay your taxes to hell! Pull your true loves off white horses! Turn into various animals and flames while being held!

157 notes

·

View notes

Text

introduction

hey folks! i wanted to give a little introduction to myself and my work, as this is my first time presenting myself publicly on tumblr. this is going to make me sound rather professional, but i promise i'm just here to do the regular ol' tumblr things: be silly, gush about things i care about, and not take myself too seriously. i hope you'll join me. :)

i'm fern maddie (she/her), a queer experimental folk artist, multi-instrumentalist, and balladeer based on abenaki land. through folk balladry and original writing, i perform songs and stories exploring themes of grief, trauma, and renewal.

***please note: my approach to folk music is adaptive, interpretive, critical, queer-feminist, and inclusive. white supremacists, "folkish" nationalists, terfs, or anyone who engages with english-language folk literature as a tool of western cultural "purity" will be blocked***

buy my music on bandcamp

listen on spotify

watch some performance on youtube

more about my work below the cut....

past projects

ghost story - my debut album, released in 2022. ghost story was named the #2 best folk album of 2022 by the guardian, and one of the top roots albums of the year from npr music. across 10 tracks, it explores the stories we inherit from the dead -- both our personal dead and cultural dead -- through a queer-feminist lens. includes a critically-acclaimed interpretation of the ballad "hares on the mountain" (roud 329), as well as the ballads "the maid on the shore" (roud 181), "northlands" (roud 21) and a queer re-framing of the scottish shepherding song "ca' the yowes."

north branch river - my debut EP, released in 2020. across 6 sparse tracks and spry banjo-playing, it explores the intimacy and pain of our tenuous relationship with the natural world. includes a re-interpretation of the ballad "the elfin knight" (roud 12), and the original song "two women," inspired by selkie folklore.

of song and bone - of song and bone is a short-lived podcast i produced a few years ago. there are only 3 episodes out, but they illustrate some of my scholarship about folk balladry and my own relationship to balladry as a literary tradition. FYI: i would probably frame a few things differently if i were re-recording the podcast today (ideas and language evolve!). perennially thinking about making more, but we'll see.

currently in development

way to live - way to live is my second studio album, currently in production. as of this writing, way to live includes 8 tracks, and similar to my previous work, combines original songs with folk ballads, though with a greater share of personal storytelling than my earlier records.

said the false nurse - this is a piece of adaptive short fiction i'm currently developing. it's a deeply sinister queer re-telling of the horror ballad long lankin (roud 6), set in the 1620s in the north of England. stay tuned for process updates!

adult children - this is a full-length original novel and associated concept album i'm developing. it's set in contemporary rural vermont, and focuses on a group of adult siblings, their dying father, their failing farm, and the new arrival who threatens their co-dependent bond. the associated rock opera will be written in a folk-rock style with digressions into folktronica and country.

#folk music#traditional folk music#folk balladry#dark folk#folk noir#folk horror#historical fiction#ballads#child ballads#roud index#fern maddie#singer songwriter#folk lore

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

it's my birthday, so as a hobbit present to you all I humbly offer this thing I wrote: a novel length (71k) original work, posted on ao3 because that's where my people are. It's a slow character driven contemporary fantasy about a software engineer's queer awakening, and it's also a retelling of the ballad Thomas the Rhymer. It's more Becky Chambers than Tamsyn Muir, but it does have a lovable dumbass protag falling in love with incomprehensibly ancient weirdos with mysterious agendas. I'm mortified to have ever written it so I promise I won't mention it again.

#writeblr#original work#urban fantasy#contemporary fantasy#fantasy romance#t4t romance#child ballads#thomas the rhymer

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Greenfinch the Bard sings the tale of Reynardine: a fox among men (uncomplimentary)

#bard#bardcore#ballad#Reynardine#child ballads#making a tiktok OC just to record child ballads is an extremely normal response to getting laid off imo

28 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Twa Corbies” wood engraving, 2019

#forgot about these lol#print#Illustration#art#crow#raven#folk#folk music#child ballads#skull#bones#ribcage

440 notes

·

View notes

Text

I love Tumblr because I can get obsessed with a Scottish ballad from the 1500′s and discover that there is indeed a fandom for it

#It's Tam Lin#I'm obsessed with Tam Lin#(again)#but really what maiden isn't obsessed with Tam Lin#Janet gets it#and thankfully several other tumblr users get it too#tam lin#tamlin#child ballads#francis child#francis james child#folk#folk songs

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

You Look So Good In Blue | Y.H. Huang

Inspired by Child Ballad 16.

When a teenage fling mutates into something vast and terrifying, two seventeen year olds at a certain mid-tier college in Singapore make a desperate plan to control their future, earn their parents' love (or at least respect), and get the hell out of this school for good.

i. the daughter

It's whispered in the kitchen, it's whispered in the hall

The broom blooms bonny, the broom blooms fair,

The king's daughter goes with child, among ladies all

And she'll never go down to the broom anymore.

It's whispered by the ladies one unto the other,

The broom blooms bonny, the broom blooms fair,

“The king's daughter goes with child unto her own brother–

And they'll never go down to the broom anymore.”

Sheath and Knife, Maddy Prior

-

/r/sgacads

is st cecilia rly a pregnancy school?? [o levels]

/u/anxiousorange

hiii sorry for the 29583th school admissions post today lol but i just got my o level results back and they’re pretty ok ^_^ so i was thinking of going to st cecilia junior college since it’s near my house but the more i hear about it the more i want to reconsider… like apparently the people are very party type which is not really my thing?? and ofc everyones heard about how its got the highest pregnancy rate in sg o_0

is this true? or just say say one

comments (8)

/u/academicweapon

As a SCian it’s not true LOL none of us get bitches

/u/theatrekidaf

skill issue

/u/sharpsdisposal

we’re too busy failing physics :/

/u/zombiegrave

q: how many scians does it take to change a lightbulb?

a: none. they like it better darker

/u/aw_bass34

Q: What’s the only test SC girls can pass?

A: Pregnancy test :P

/u/gregorythomas91 [s]

Damn old rumour, probably from 1990s, 2000s around there. But it’s not really unfounded. Especially with what happened in 2008.

/u/anxiousorange

what happened? im scared lol

/u/gregorythomas91 [s]

You haven’t heard meh? It was a big deal back then, I'm shocked they've covered it up that well. Let me try and remember.

-

You never told me what really happened over those few blistering months in 2008, but I guess I wasn’t alone in that. Even when the newspapers shoved a mic in your face, even when you were being grilled by the lawyers, even when you were standing on that trap door, waiting for the drop– what really happened was a secret you’d bring to the grave.

So it’s all inference and extrapolation and linear correlation– sue me. How else am I going to make sense of that moment? How else do I come to terms with why you did what you did? Could I have known? Could I have stopped it? Was I even, when it came down to it, your friend– or was I just somebody who let you copy his lecture notes?

I don’t know. What I do know is this:

It was some mid-week mid-afternoon, indistinguishable from any other. The bell had just rung, and the whitewashed corridors were packed with sweaty kids rushing to PE, squeezing past those dragging their feet from class to class. We were part of the latter group, squinting against the September sun as we ambled across the quadrangle to home class. Above us, the school motto loomed in oversized light-blue letters: Remember you are in the presence of God.

I was mentally calculating how long the Malay stall queue would be when you said, casual as always, “Eh, pass me your market failure notes later, can? I’m yellow-slipping after GP.”

I raised an eyebrow. You weren’t a stranger to leaving school early, but you’d been doing it more and more often lately, and at this point I hadn’t seen you stay for Shooting in ages. As your club captain, I was supposed to be concerned. As a friend– well, I was intrigued. Of course I’d heard the rumours, passed from homeroom to homeroom, Friendster account to Friendster account. Who in St Cecilia’s hadn’t? “Is this related to whatever you and Camilla Wong have going on?”

“Cam’s not my girlfriend,” you said, after a brief, completely unsuspicious pause.

I snorted. “She doesn’t let anyone in this school call her that but you, dumbass. ”

You ducked your head down to hide a smile, your dress-code fringe falling into your eyes. It was a strangely endearing habit. “Fine lah. We’re– seeing each other.” Then you continued, hurriedly, “But don’t let anyone else know, OK?”

“Fine, I'll write you off CCA for today. But don’t make it a habit, ar? Hold pen, not hold hand.” Despite myself, I grinned. Sure, the two of you made an unlikely couple. Wong was an ex-Convent girl and student councillor, all relentless energy and long hair tied so high it was prone to hit people when she spun, while the only time I’d ever seen you really alive was behind the barrel of an air pistol. Back then, I thought it was cute. Opposites attract– wasn’t that the backbone of any drama worth its salt?

I wouldn’t realise, until later, that despite how different the two of you appeared, at the core of it you were the same– pale and skinny and drowning in your school uniform, searching for exits the moment you stepped into a room. Always, always halfway out the door: of your school, of your body, of the life you knew.

But back then it was just a September afternoon, and we were only seventeen. You smiled back at me, all cheer, like you saw something I didn’t, like you saw something I never would.

-

In the end, though, this isn’t my story. This is yours. So let’s tell it your way.

-

The newly minted 1T26 trickled slowly from assembly into the classroom, chopeing the best desks and nervously rotating between the same few ice-breakers: orientation, secondary schools, O-Level points. As you entered, you cast a glance over the sea of blue pinafores and green pants. Still reeling from the sheer increase in the female population, you took a desk at the back, between the ancient, peeling noticeboard and the window looking out on the covered tennis courts. You were tall enough to see over all the heads, anyway.

Soon, your home tutor arrived, a round-faced lady toting an oversized Cath Kidston duffle bag, and wrote her name on the board in neat block letters: Mdm Alvares. The class stood to greet her, chairs scraping hurriedly against the linoleum. She beamed back, her smile all teeth, and was busy setting up the visualiser when the door slammed open.

The class spun in their seats. “Sorry,” the intruder sheepishly said, leaning against the doorframe. Some of her hair had fallen half-out of her high ponytail, her pinafore already wrinkled at the hem. A dusting of freckles covered her pink cheeks.

Mdm Alvares squinted at the girl, then the laminated name list. “And you are?”

“Camilla Wong.”

Mdm Alvares looked out over the class, scanning the rows, and her eyes landed on an empty seat in the corner whose sole occupant was your beat-up Jansport. Realising where this was going, you sighed, putting your bag on the floor.

Camilla smiled, made her way in–

and put her bag down at another empty seat, half a class away.

–

There was nothing in this world you hated more than 4PM Maths lectures. That day the aircon was actually working, which you would normally have been grateful for, except for the fact that that sharp, recycled wind was blasting directly at the very back rows of LT5, right onto your face.

You were trying so hard to 1) figure out plane vectors and 2) stop yourself from getting hypothermia that you wouldn't be able to recall, later, the exact moment that Camilla fell asleep on your shoulder.

When you realised this, you froze. Oh, you thought, and didn't know what else to think. On one hand, it would’ve been so easy to wake her. Just a poke from your pen, and she would’ve jolted up almost instantly. On the other hand, though, her long eyebrows brushed against her freckled cheeks, and her chest rose and fell in these small, slight motions, and–

Before, you had only ever seen her as a baby-blue blur in the corners of your sight, always in motion even in the earliest of classes. But Camilla, asleep, tucked in the crevice between your shoulder and neck–it felt fragile, thrumming, tense. Like something made of glass, nestled gently in your hand, that it would only have taken a squeeze to splinter.

The next twenty-two minutes were the longest twenty-two minutes of your entire life so far. Even so, when the bell rang and Camilla pulled herself upright, you found yourself missing it already.

–

After that, it was like a switch had been flipped in your brain. It was only then that you began to really Notice Camilla, capital N, italics. You noticed her with her head bowed in mass, noticed her shoving fishball noodles into her mouth at lunch, noticed her arguing with your classmates over technicalities in GP. But you noticed her the most in Monday zeriod house meetings, when the artificial grass glimmered with dew and the syrupy dawn light made the whole world seem like a Hollywood coming-of-age movie. You watched her toss her braids over her shoulder, wipe the pearls of sweat off her flushed face. Her red, red shirt rode up as she stretched, revealing a sliver of pale flesh above the waistband of her shorts–

It took until then for her to notice you Noticing. Her eyes flickered over to you, she winked, and blew a kiss.

You felt as if you’d walked out onto the PIE and been hit by a truck. It was a wonder every single smoke alarm in the school didn’t go off right that moment–a cacophony of ringing like firecrackers all strung up, exploding pop-pop-pop from the foyer to the science block to the hostel. It swallowed every other sound, every other thought. Then she turned away, a grin still lingering on the corners of her lips.

–

During one of your lunch breaks, Camilla pulled you out of class. She had to ask you something about your PW survey, she said. As far as you were aware, you weren't in the same PW group. You knew this. She knew this. The entirety of 1T26 knew this, too, so you headed down to one of the wooden picnic tables underneath Block D, the one tucked beneath the staircase next to St Pat’s room. Both of you hovered awkwardly around the bench for a moment, doing the calculations in your head–how close to sit? What to say? You shifted from foot to foot.

All of a sudden, Camilla slammed her hand down on the table. You jumped. “Walao eh. I legit can’t do this anymore. Is this a Thing? Are we having a Thing?”

You swallowed, eyes darting.

“Make up your mind, sia.” She rolled her eyes, laughing under her breath. “St. Francis boys, I swear.”

“No, wait, yes–” The words spilled, embarrassingly and pitifully, out of your mouth. You feared you were not beating the all-boys’ school stereotypes that day. “I mean, I did, but, um–” Just stop, your brain chanted. What're you saying? You're only making it worse. Kill yourself. Kill yourself. Kill yourself.

“So that’s a yes,” Camilla said, and surged forward to shut you up herself.

–

The next thing you knew, you were stumbling into the stairwell together, the door banging noisily shut behind you. “Why–” Camilla started, and you said, “Nobody ever uses Staircase 6. Now come on.” You pushed her up against the curved concrete wall, not caring that the low ceiling scraped against your head. There was that wild, exhilarated look on her face again, like she still couldn’t believe that she was actually doing this. Beautiful, even in the dull grey light. Her nails dug crescents into your skin.

The air was all heat, sweat, too much cherry blossom perfume. You worked at your tie–quicker than you’d ever been able to in all your years of schooling–as she undid the buttons on her uniform shirt, revealing the freckles that dusted her pale shoulders like so many stars. As you unbuckled her bra in one quick motion, she gasped, then giggled. “Damn, Yeoh. You’re good at this. Is there anyone you haven’t told me about?”

In between kisses, you came up for air. You could've made a joke about not having many opportunities to practise in St Francis, but the real truth was that your desperation shocked even yourself– this wasn’t the careful boy that your pastors, parents, teachers, knew. Your heart threatened to burst from your chest like the bullet from a gun. For the first time in sixteen years, it felt– really felt– like you were fully alive.

“Just you, Cam.” You dipped back down. “Only you.”

ii. the yew tree

He's ta'en his sister down to his father's deer park

The broom blooms bonny, the broom blooms fair

With his yew-tree bow and arrow slung fast across his back

And they’ll never go down to the broom anymore.

You made close acquaintances with every dark corner of the school. When June came, you merely shifted your meeting points closer to home– behind heartland malls in Tampines or in the nooks and crannies of Cam’s sprawling landed estate along Cluny Road. Neither of you were sure, yet, if you were doing it Right– things like bubble tea dates, strolls in Botanics, or mugging in NLB (god, you should have been mugging, mid-years were in a week and neither of you had cracked a book). But if it wasn’t capital R Right, why did it feel like it was? You thought you had developed a case of myopia–Cam in focus, everything else blurred.

All that to say: the holidays were closer to ending than beginning when you and Cam found yourselves in an overgrown grassy patch tucked somewhere in between a storm drain and the wrought-iron back gate of some minister’s landed property. It had sounded a lot more romantic in theory, but the cloudless sky was the same powder-blue as your school uniforms, and the sun beat down like it had a personal vendetta against you. There was nothing much for shade except for a single banana tree, which you lay crumpled under, sweat-sheened and reddened. The last of the endorphins were beginning to wear off.

Cam’s ringtone cut through the air, a chiptune rendition of some Green Day song. She sighed, then propped herself up on one elbow as she picked up her phone. Her hair was loose, cascading down her back like smooth dark water. You fought the urge to run your hands through it.

“Ba!” she chirped. The cheer didn’t show on her face. “Ba, of course I'm still at the library. I’m with Lucia. Yes, Ba, I’m sure. Don’t call her, can?” She flinched as though she’d been slapped– a familiar, instinctual tic. “Sorry, sorry. I’ll study hard, I promise. Byebye.”

She hung up and sighed, leaning backwards. “I think I’ll need to go soon.”

“Soon,” you promised. You were lying flat on the warm grass, arms crossed over your chest like you were about to be lowered into the grave.

“Soon,” Cam repeated. “Fuck, I hate that we have to sneak around like this, sia. I keep thinking that he’s going to jump out at me from any corner, that any random passerby can tell I’m not where I’m supposed to be. It’s like this whole island has eyes, and maybe it does.” As she lay back down beside you on the grass, her oversized t-shirt–Camp Veritas Counsellor 2007–drooped down to reveal the blades of her shoulder, the ones you’d kissed just moments ago. Her voice lowered. “You know ah, the moment we get our A-Levels back, I’m getting out of this city. Australia, London, LA, anywhere. There’s nothing here for me.”

“No leh.” She can’t say that, you thought, pettily, awfully. She had a mansion and a scholarship and a real iPhone. She had the freedom to just leave. To go somewhere without worrying about the money. You had– what? Parents on the edge of divorce and a bankrupt family business? So much for inheritance. So much for a glorious kingdom. Then you had banished the thought from your head. “You have me.”

“I guess I do.” There was a pause. Then she asked, quick and soft and desperate: “Hey, if I asked you to do something, you’d do it, right?”

You reached over, squeezing Cam’s hand tight in yours. The leaves of the banana tree shivered. “I’d do anything for you,” you told her, and it was true. It was really true.

–

Your grades wobbled, then declined, then plummeted, and you found, to your surprise, that you couldn’t care less. You’d made a lot of bad decisions in your life. Try as you might, you couldn’t count Cam among them.

This, then, might have been why you were lying on your bedroom floor, squinting at your Nokia at four AM on a Monday morning. An empty can rolled lazily from your hand, on an epic journey across the glossy faux-marble floor. The house, for once, was still. Even your parents’ screams had petered off about an hour ago. The silver light from the HDB corridor fell through your windows in slits, providing just enough light for you to see the tiny phone screen. With the phone’s small buttons and your clumsy fingers, it took a long time for you to dial the number, but none at all for her to pick up.

“Cam,” you whispered, “Want to see you.”

“Jesus, Yeoh, it’s a school night.” Her voice was gorgeous like this, low and blurred. She only ever used this voice with you: when her raw-bitten lips were pressed against your chest, your ear, your– You shifted. It didn’t help.

“Cam, Cam, Camilla.” Her name rolled off your tongue like a litany, sharp and needy. “Can talk a while or not?”

“Are you drunk again?” she teased you. On the other end, her sheets rustled as she sat up. Although you hadn’t ever been in her house before, you could reconstruct it well enough from the blurry webcam pictures she’d sent you: piles of assessment books, porcelain cross, ceiling fan. And she– beautiful, beautiful, feet kicked up against her headboard, black hair spilling over the flowery sheets, the smile evident in her voice. “Help lah. How–”

“Miss you,” you murmured, by way of an answer.

“I miss you too.”

“Want to meet you. Want to talk to you.” Then, because you were three cans of beer deep and loved making (aforementioned) bad decisions, you charged on: “You and I, we never talk.”

“I know we haven’t met in a while. It’s not my fault I was sick–” Her voice wavered a little, then bounced back to its chirpy cadence. “But we talk all the time, though. We literally talked in class yesterday. I’m talking to you now.” Cam laughed. Her laugh still sounded to you like the first day of the month– every church across the island breaking into bellsong, light and birdlike in the hot blue air. It was cliché, you knew. You didn’t care. Perhaps you were in too deep to care.

“No,” you insisted, but you didn’t really know what you were saying, or why you were saying it at all. “We don’t.”

“We don’t,” she said, then fell silent.

The funny thing about the two of you was this: Over the past few months, you had seen each other stripped bare, worn to the bone with want, more times than you could count. But the both of you knew, all right, that there were things that you couldn’t– that you didn’t say. Things that were secret even to yourselves. The scars on your forearm, the bruises on hers, the way she looked at you when she thought your mind was elsewhere. Those three words, weightier than any false promise you’d whispered against each other’s skin.

“Staircase. Tomorrow. I need to tell you something.”

–

That night, you dreamt of flying.

You weren’t a bird, weren’t yourself– just bodiless, incorporeal, sweeping through the hallways of the college like a ghost. You phased through the auditorium doors to see the loose ceiling tile, the one that had been hanging over your heads like a guillotine all term, topple to the ground in one fantastic crash, sending students fleeing out the doors and into the foyer. You fled with them, but the ceiling fan in the foyer was spinning just a bit too hard, just a bit too fast, and the students screeched to a halt just in time to catch it falling, an angel with clipped wings. It broke in two over the staircase railing, knocking down the tables and the notice boards, pulling down the ceiling with it. Then the chapel was the next to go, the shattering stained glass catching the light in a thousand colours. As you raced up the corridors, the destruction raced up, up, up, alongside you, past the staff room and canteen to the lecture halls, the classroom blocks, the PAC, every single building in the college folding in on itself like so much wet paper. Block J detached itself cleanly from its precarious perch, tipping head-over-heels into the field. You couldn't hear a thing, but you could imagine what it sounded like: the earth itself breaking, rapture the other way around.

Then you crossed the lower quadrangle, where two little blobs of baby blue lay pressed against each other’s bodies. Even without descending, you already knew who they were. It was strange to watch yourself like a movie. When you were younger, you'd thought that this was how God saw the world, top-down, like a player peering at a chessboard. When you’d failed an exam for the first time, you'd cowered under a table-cloth to escape His wrath. You’d stopped believing in a lot of things as you grew up, but you could never kick that instinct to flee, that inescapable, intrinsic fear that the presence of God really was everywhere: under a table, in a school, in every splitting cell.

The boy on the ground turned his face towards the girl, tucking a strand of hair back behind her ear. She smiled infuriatingly, endearingly, back at him.

The school came down on them.

–

Most of the morning was taken up by this awful college event that you’d totally forgotten was happening, all cheering and sweat and thirty-eight degree heat. It was only when the day was coming to a close, then, that Cam and you could sneak away past the computer labs and guitar room into Staircase 6. As you entered, Cam pulled out something from the pocket of her sweater–an admin key–and latched the door behind her with a deliberate click. You blinked. “How’d you get that?”

Cam didn’t say anything, just tucked the key in the pocket of her oversized school hoodie. There was something strange and tense about her, stranger and tenser than she had been all term. She walked up to Level 4, where the sky through the grilled window cut long slices of light onto the concrete floor, and sat down on the top step. You sat down next to her.

She breathed, imperceptibly, in and out, looking straight ahead. The question rushed out in a gasp.

“You told me you’d do anything for me, right? I need you to kill.”

iii. the arrow

And when he has heard her give a loud cry,

The broom blooms bonny, the broom blooms fair

A silver arrow from his bow he suddenly let fly.

And she’ll never go down to the broom anymore.

-

WONG CHIEN PING

The New Paper, 1998

WONG: To me, family– family always comes first. My kids always come first. You know ah, I’ve got five children. Four boys, one girl.

INTERVIEWER: Wow.

WONG: [Laughter.] Can be a handful at times, lah, but what can you do? As I was saying, right, when I look at my kids, I’m thinking about everything they could be. Lawyers, doctors, maybe even MPs like me. [Laughter.] And I think about how Singapore’ll change in ten years, fifty years, a hundred years. My youngest, Camilla, she’s going to graduate from university in the 2010’s. In a new century. What’s Singapore going to look like then?

INTERVIEWER: Mhm.

WONG: I want to make Singapore a place where my kids can grow up safely. Where they can have a future.

-

For a moment, all you could do was laugh. Then you stopped, of course, but the echo lingered. “Cam?”

Without meeting your eyes, she lifted up her sweater. The first thing you’d thought was that she’d forgotten to bring her house shirt– she was still in uniform. Then you realised that her shirt was unbuttoned at the bottom, and her skirt was unlatched, and there was a solid, unmistakable, swell to her stomach.

The world tilted on its axis. There was no way this was happening. This was a really terrible prank. She’d stolen a prosthetic from Drama. It had to be something, something other than this, something other than a child– You made an inelegant noise, some spluttered form of protest. “Oh.”

“Oh,” Cam agreed, unhappily.

You instinctively reached out to touch her bump, like you’d seen in the soapy Mediacorp dramas Ma always watched. You didn’t feel anything. Wasn’t there supposed to be some sort of parental instinct singing to you; love, love, love all through the water and the flesh and the blood?

“Didn’t you listen in Bio? You can’t feel the heartbeat yet. Not for a while, but not for long, either,” she said. “Not until I can’t hide it anymore.”

“Oh.” You didn't know what else to say. You pulled her into your arms, and she pressed herself against you, body against body. Like stragglers hiding from the cold, except it was thirty-five degrees outside, the air the same dull dead warmth that school air always was. She turned her face away, but you could still see her eyes go glossy, hear her take those shallow breaths. "I'm so sorry."

You couldn't begin to imagine what she was feeling, how much she'd lost in that instant when she knew she was carrying a life that wasn't hers: the scholarship, the law school, the clear American sky she'd never see. The future rushed out before you, a landscape vast and desolate, and you found yourself unable to picture it except for your mother's face, crumpling in on itself, her world imploded in a single moment. Thinking: all you had to do was study hard. We gave everything for you, pinned every hope on you, and this is what we get? Saying: stupid boy. Stupid, stupid boy.

You don’t know how you say what you say next, but you do. “So. You want to- to kill it?” It, it, it. Still an it.

Cam laughs wetly. “Almost there. Kill–” the pronoun trips off her tongue– “me.”

-

ST CECILIA’S JUNIOR COLLEGE

CAMERA 235

12:28:03

YEOH shoots to his feet. WONG does too.

YEOH: You can’t just say that–

WONG: Just shut up for a moment and let me explain, can?

YEOH shuts up.

WONG [with a wince]: Sorry. But you know my father lah. You know how he is. He’ll have my head.

YEOH: What’s the worst he can do ah? Pack you off to some boarding school overseas?

WONG takes a sharp breath.

WONG: It’s not about that. It’s about the fact that he’s worked his whole life for this position. If he ever finds out what we’ve done, his career jialat liao, just like that. Every single day for the rest of my life he’ll look at me and only see a disappointment of a daughter, a stain on the family name. I snuck around and I lied to his face and I bribed my friends for alibis but at least for seventeen years he didn’t know better. He called me his princess, his golden girl, and he meant it. Now all of that’s gone. Or will be gone, I guess. I don’t know how I’d live without that.

YEOH: He doesn’t need to know. You understand that, right? There are ways to get rid of it, I mean, there has to be some way–

WONG: That’s the fucking problem!

WONG turns away, stifling a sob.

WONG: Before I formed you in the womb I knew you–

YEOH [instinctively]: And before you were born I consecrated you.

WONG: This is our child, Yeoh. This is a human life.

YEOH: Better any other life than yours.

A long pause.

WONG [overlapping]: You can’t mean that.

YEOH [overlapping]: I can. I do.

YEOH ascends one step. YEOH stares at WONG as if he’s daring her to say something, until WONG begins to cry. YEOH freezes for a split-second. He reaches for WONG, whispers something inaudible in her ear. WONG reaches up and kisses him in response. After a while, WONG extricates herself with an expression that seems almost like a smile. She walks over to the railing and leans against it. YEOH follows her.

WONG: I’ve always told myself I want to be a good person, but maybe the real truth is that I didn’t want my dad to figure out otherwise. Maybe all of that hiding was for nothing. Maybe it was only a matter of time before he found out who I really was, deep down: rotten. Impure. That woman Jezebel, who calls herself a prophetess.

WONG: And, sure, I can sneak away to a clinic, God knows we can afford it, I can do whatever it is girls do in movies with the clothes hanger or the back alley. But if my life after this is all an act– what’s the point, if I already know where I’m going when I go? I’m tired of keeping secrets, trying so hard to keep this part of my life from him– when one day I’ll slip again, I know it, and the whole house of cards is going to come crashing down. If I die now, all my sins are going to die with me. He’d be happy, and I’d be loved, and you–

WONG [almost envious]: You’d never understand.

YEOH tilts his head downwards, fringe falling over his eyes. He starts to say something, then stops.

YEOH: I do understand.

-

Like so many other people you knew, you never meant to go to St Cecilia’s. Everyone said you could make Temasek, maybe Victoria. Tampines at the very least. And you'd believed it, too, until you didn't anymore, until the college you were going to became the least of your worries.

When did you stop believing you’d ever have a future? It wasn’t a single moment so much as it was a series of them: stepping over the yellow line when waiting for the train, trying to find footholds in the railing of every overhead bridge, your eyes always flicking to every exit you could take. The words you said under your breath in prayers weren’t Our Father who art in heaven but a litany only you knew: I don’t have to do this. I don’t have to keep going. I can leave any time I want. For as long as you remembered, you’d already been halfway gone.

It was a comforting hypothetical, until it wasn’t, and suddenly you found yourself on the bathroom floor at three in the morning, a week before prelims. The cool white light bounced off the tiles, the mirror-cabinet above the sink hung ajar like it was beckoning you, and you were so, so exhausted. Why were you trying so hard? What were you even studying for? No matter what college you went to, the future would always be blurry and grey. Test after test after test, then onto– what, exactly? You’d never been able to imagine yourself past sixteen. You’d never be able to imagine yourself more than half-alive.

You’d tell the psychiatrist later that you didn’t remember the rest of the night, but that wasn’t true. You remembered the pills. You remembered the blinding, fluorescent pain– and through the pain, your father’s face, your mother’s voice. 911 on the cordless telephone. The ambulance. Changi Hospital. When you’d finally woken, there was a split-second where all you could see was white, and all that came to you was a rush of relief– until the white coalesced into white walls and white sheets and a ceiling spotted with air-conditioning vents, and you could almost laugh at yourself for expecting anything different. If you’d succeeded, anyway, it wouldn’t have been white.

So you failed both at dying and at Chemistry. That was fine. You took the two points off for affiliation. You took the 5AM bus. You took the desk at the corner of 1T26. That was fine too. You swore you didn't care about any of it, and you didn’t, you didn’t. Then Cam happened, and suddenly you did.

But you couldn’t shake the memory of that night in the hospital, your parents whispering next to your bed when they thought you were asleep. For once in their life, they weren’t at each other's throats. What’s wrong with him? your father demanded in Chinese, betrayal running like cracks through his voice. I don’t understand why he would do this to me. In response, your mother only sighed. Stupid boy. Stupid, stupid boy.

-

The story came uneasily to you, like writing an exam for a subject that you hadn’t touched in months. Once you were done, Cam turned to you. If it was anyone else, they would’ve said something benign, something untrue, like, I’m sorry or I’m glad you didn’t die. Instead, because this was the Cam you’d always known, she asked, “How much did it hurt?”

You thought about the answer for a long while. Then you said, “If you do it right, only for a moment.”

She laughed, then, throwing her head back with the force of it. For a brief, blasphemous second, you’d never seen anyone so beautiful: fair as the moon, clear as the sun, terrible as an army all set in battle array. It was the kind of beauty wars were fought over, the kind any man would get on his knees for– to be knighted, to adore. And she’d chosen you (you of all people!) The fact made you dizzy with its weight.

“So.” Her voice brought you back to reality. It was casual as anything, like she was discussing essay outlines or Physics solutions instead of– whatever this was. “I was thinking about the stairs, right? If you pushed me, hard enough, it’d look like an accident…”

Below you, the concrete staircase looped in on itself, down, down, down. Tall, yes, but only three stories, not enough to kill. Not if you wanted to be sure. When you told her as much, she frowned, swearing in Chinese under her breath. The two of you bounced around a few more ideas, but none of them seemed to stick. You fell silent, tapping out meaningless rhythms on the rails, as you considered what you’d been dancing around since she’d asked you to kill. A competition-grade air pistol, a shot at just the right angle– it’d be, well, if not easy, at least simple. Less up to the fates.

There was only one problem with that plan– it’d no longer be an accident. There’d be police, lawyers, fuck, maybe even journalists. Your juniors would whisper about it for camps and camps to come. You couldn’t feign innocence with a shotgun, couldn’t frame the act of pulling the trigger as anything but what it was.

So, fine, they’d hate you. They’d shred all your certificates, put your photos face-down, pretend they’d never had a son. So what? Boy hung from his bedroom fan, boy hung from the prison beam. Whatever formula you used, the result was still the same: you’d be gone, and they’d be free. Besides, there wasn’t any way St. Cecilia's reputation could possibly be worse than it already was.

“I think–” you started, suddenly, “I might have a solution.”

iv. the grave

And he has dug a grave both long and deep,

The broom blooms bonny, the broom blooms fair

He has buried his sister with their babe all at her feet.

And they’ll never go down to the broom anymore.

INTERVIEWER: You didn’t notice the keys were gone meh? I thought you were the captain.

THOMAS: The captain doesn’t carry the keys, sir. Um, he was the armourer, sir, he’s always had them. Since the beginning of the year.

INTERVIEWER: So you weren’t aware that Yeoh and Wong entered the armoury at 12.39 PM and retrieved a [pages ruffling] .25-calibre Baikal air pistol.

THOMAS: Of course the alarm went off, lah. To notify the teacher-in-charge. But he told Miss Judith he forgot his water bottle inside, and she was in a hurry anyway–

INTERVIEWER: She believed him?

THOMAS: Miss Judith’s always had a soft spot for him, sir. And we all trusted him. That’s why we made him the armourer. Of course he was quiet, um, but in a calm, reliable sort of way. Out of all of us we thought he’d be the last person to do what he did. [laughter] I trusted him– oh god–

INTERVIEWER: Calm down, boy.

THOMAS: Sorry, sorry.

INTERVIEWER: Can continue or not?

THOMAS: Okay. Can. Go on.

-

Laughing the loud and triumphant laugh of the already dead, you and Cam crashed back into the staircase landing like you’d done so many times before. How many giggling, short-lived couples had this place borne witness to? The seniors who’d winked and nudged you in its direction must’ve learnt it from their seniors, who’d learnt it from their seniors in turn– back and back it went, a story in two-year cycles, mutating each time it was told. A haunting, a myth, a folk song.

Cam, leaning back against the wall, ran her hands along the sleek pistol. She looked, still, beautiful: even after the run, after the tears, despite the baby. If you hadn’t seen her before, you couldn’t have guessed that she was the kind of girl who would ever cry. “It’s like I’m a spy.”

“I mean, we kind of are, right? People are going to start getting suspicious soon. We should do this quickly.” You shot a furtive glance through the window in the door. The corridor, as always, was dark– the lightbulb had been busted for a long, long time.

“Soon. Won’t take long, right? Just–” She aimed the gun at her temple, mimed pulling the trigger with a grin. Miss Judith had trained you well– your first instinct was one of sheer panic, of tripping over your own feet in your haste to rip it from her hands– but you didn’t do any of that.

Instead you only swallowed, shifted. “Just like that I don’t think is strong enough. It’s not real ah. Can’t do that much damage. Um, can I–”

Downstairs, someone shouted. Cam shoved the gun in her hoodie pocket. You stopped breathing. Something clunky was being dragged across the floor, chatter following in its wake. But no one had opened the door yet, so when the clamour finally died down, Cam removed the gun from her hoodie and passed it to you.

In your hands, the pistol was cool, familiar, deadly in a way it had never been before. It reminded you that despite any pretences to precision or skill or patience, this sport was, at its roots, a killing sport– drawing blood and blood and blood again.

You’d only been a shooter for a few months. You'd always been a chess club kid in secondary school, and in St Cecilia, you’d even applied for Strat Games before you walked into the interview, saw an old classmate, and walked right back out. At least shooting was a singular sport. No emotions involved, no one to fool, no one to ask you what happened.

About a week or two past orientation, you’d hit bullseye for the first time. You didn’t notice, at first, still reeling from the ricochet, until Greg shouted and the club gathered round and you saw that tiny wound on that tiny target, fifty whole metres away. In another few weeks, it’d become routine, but you never forgot that first time: the breath held, the trigger pulled, the bullet sailing through the air. The gun like an extension of yourself.

She must’ve sensed something had shifted, because she hurried out, “If you don’t want to do this, just say, OK? If you really want, we can– I don’t know, figure something out.”

You’d do anything for me, right?

Okay, so maybe you were helping her because you knew what it was like to be so tired that you wanted nothing more than to be gone. You knew what it was like to fail– your mother’s eyes avoiding yours, the flat stinking with shame, cut fruits slid under your door like an apology– and you knew, you knew, out of all the people in the world she didn’t deserve it.

But maybe you were helping her because you’d never known anyone who could go to their grave with a smile quite like her, brilliant and foolish and brave. It was your hand brushing hers under the desk and her laughing with her head thrown back and the two of you sharing earphones on the bus. It was the fact that in life or death, you’d never wanted anyone but her.

So, fine. The moment you’d opened your eyes in a hospital bed, you couldn’t find it in you to care about Heaven or Hell or anything in-between, couldn’t care about a God who’d turned his back to you as you were bleeding out. But even the staunchest of atheists could admit that it was nice to believe that you’d been brought back for a reason; that more than any grade you’d ever gotten or any target you’d ever hit, the greatest achievement of your time in college– okay, your entire short and sorry life– was this: to love her, to kill her, to be loved, impossibly, in return.

You kissed her like it was an answer. Maybe it was. You’d never know.

–

Just like you’d predicted, it wasn’t easy, but it was at least simple:

The muzzle dimpling her button-down shirt. Her heart beneath the gun, frantic and wild. Her smile– smug, inscrutable, like she was getting away with some great and treacherous heist, like she’d stolen something you’d never notice missing until it was too late. Coloured-in Converse perched on the edge of the top step.

A moment to aim. Less to fire.

A crack. A body arching backwards, falling, falling, falling. A body against concrete. A body with its neck all wrong– no, that wasn’t right. Two bodies. One body. But what was the difference, really?

Somewhere, someone was singing.

–

I got tired of waiting

Wonderin' if you were ever comin' around

There was a boy at the edge of the canteen, that isolated corner where the cafe used to be before it went bankrupt and left neon-yellow wreckage in its wake. I could just barely make him out through the other kids who’d swarmed like moths around the speakers we’d looted from the grandstand, a do-it-yourself rave all our own. We were seventeen and free from Promos and knew every word to every song on the radio and there was nothing in this world to worry about, nothing at all.

My faith in you was fading

When I met you on the outskirts of town

My voice faltered as I tried to peer over the heads, earning myself a poke in the ribs from Joshua from 28. The boy was tall, in uniform–on the one day we were allowed to wear house shirts? He’d be sweltering hot. He stared off at something I couldn’t see, collapsing on a bench– and the moment I saw the fringe, I knew who you were.

“Xavier!”

I painfully extracted myself from the knot of students, making my way over to you. You didn’t seem to notice me, didn’t seem to care. There was something red on your face, probably some failed attempt at Go SC! It seemed like the sports leaders had gotten to you. Funny. I’d never thought you were the type.

You turned to me.

“Xavier?”

I broke into a run.

I keep waiting for you, but you never come

Your hands were shaking, your eyes wet. There was red on your shirt, red on the corner of your lips. Shit, there was so much of it. “Are you hurt?” My brain was going at thirty miles a second. “What happened? Did you– are you–”

“I’m fine. I just–” You broke off. Slowly and carefully, like you were explaining something to a very small child, you forced out two more words: “--lost something.”

I cast desperate glances around the canteen. There was something wrong here, something I couldn’t even begin to comprehend, like standing on the edge of a cliff with a sea below you. “It’s OK, bro,” I muttered out, stupidly, awkwardly, “You’ll get it back, whatever it is. Um. You need me check with the GO? Call teacher?”

Through the thin walls, a scream rang out. The singing died a quick, violent death, but the music, still, played on.

I talked to your dad, go pick out a white dress

“No,” you said. “No need.”

It's a love story, baby, just say yes.

-

After everything– after the police, after the trial, after the drop– Wong’s father swept in and gave half of St Cecilia’s a dizzyingly long contract that boiled down to Don’t tell a soul this happened or I’ll kill you myself. Of course I’d signed it. What else could I have done?

In the years to come, I’d want to tell you about so many things: The times we’d instinctively turn in our seats to ask you about homework or classes or anything at all. The two empty desks we’d dodged for the rest of the year, even after we switched classrooms, even after they struck out your names from the class list— as if long before that October afternoon, you were already gone. The shiny, upgraded surveillance system, a threat, an eulogy, as much acknowledgement as they’d ever give you.

Now, though, I want to tell you about the staircase.

When I stepped back into St Cecilia’s for the first time in ten years, so much of it remained the same. The same old coat of paint, the same wobbly tables, the same starched blue uniform. The only thing that’s changed is the kids– how young they seem now, how they call me Mr Thomas when I’m listening and ‘cher when they think I’m not. In the spaces between classes, when the halls are full of chatter, I’ll overhear snippets of their conversation: I’m yellowslipping for Taylor tickets or Walao, my stats really CMI, like this how can pass or Wah, are you going to take her to Staircase 6? That last one’ll be invariably followed by a wink, a nudge, and loud, boisterous laughter, the kind that only teenage boys can summon up. I can’t blame them much for it. Weren’t we once seventeen too?

The staircase isn’t particularly hard to avoid. For the kids, it’s more of a novelty than anything– a quick selfie at the door during Orientation, then it’s out of their minds for the rest of the year, too far from the classrooms to be of any use. Soon enough, though, exam season rolled around, and I was on my first night study shift of the year. I didn’t have to do much– just make sure nobody escaped the well-lit confines of the library, which was just as crowded and chilly as I’d remembered it. But the campus seemed different after dusk, every flickering light a blinking eye, and I felt myself being led down the concrete corridors, past the office and the hall and the lockers, past the bulb they’d never fixed, and I unlocked the door.

It looked, obviously, like any other staircase in the school. The floor was grey, the walls white. I went up to the top floor and to the railing, the security camera swivelling as I walked. Over the railing, the stairs went down, down, down. Despite my best efforts, I couldn’t find any part of it that suggested your presence. No pale figure, no blur of light. I felt, suddenly, foolish– what answer was I seeking? Even if you’d lingered, even if you’d somehow escaped where I’d most feared you were, this was the last place you’d want to stay.

Maybe I would never really understand why you did what you did. But I’d known you, even still, and so I could say this with certainty– if there was any justice in this world, you weren’t here. You were somewhere edgy kids couldn’t gawk and giggle at you, somewhere the camera couldn’t find you. Somewhere only you knew.

An engine growled beyond the gates. Sweet and heavy in the air, the scent of flowers lingered.

I closed my eyes.

-

And when he has come to his father’s own hall,

The broom blooms bonny, the broom blooms fair

There was music and dancing, there were minstrels and all.

And he’ll never go down to the broom anymore.

O the ladies, they asked him, “What makes you in such pain?”

The broom blooms bonny, the broom blooms fair

“I’ve lost a sheath and knife I will never find again

And I’ll never go down to the broom anymore.”

“All the ships of your father’s a-sailing on the sea

The broom blooms bonny, the broom blooms fair

Can bring as good a sheath and knife unto thee.”

But they’ll never go down to the broom anymore.

“All the ships of my father’s a-sailing on the sea

The broom blooms bonny, the broom blooms fair

Can never ever bring such a sheath and knife to me

For we’ll never go down to the broom anymore.”

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

I went down a research rabbit hole the other night and it was. Something.

#murder ballads#folk songs#child ballads#obvs antisemitism is still a horrible problem but historic antisemitism was like...cartoonishly evil#antisemitism#tw antisemitism#(as usual I don't know if I'm using this meme template correctly)

11 notes

·

View notes