#elizabeth kirsch

Photo

Virginia Jaramillo: Principle of Equivalence, Edited by Erin Dziedzic, Contributions by Matthew Jeffrey Abrams, Barbara Calderon, Iris Colburn, Elizabeth Kirsch and Courtney J. Martin, Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art, Kansas City, MO, 2023 [Exhibition: June 1 – August 26, 2023]

#graphic design#art#geometry#mixed media#exhibition#catalogue#catalog#cover#virginia jaramillo#erin dziedzic#matthew jeffrey abrams#barbara calderon#iris colburn#elizabeth kirsch#courtney j. martin#kemper museum of contemporary art#2020s

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

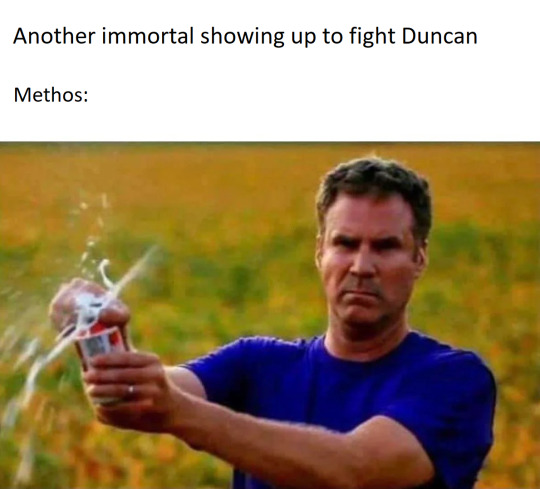

#highlander the series#meme#memes#duncan macleod#adrian paul#stan kirsch#richie ryan#amanda darieux#elizabeth gracen#jim byrnes#joe dawson#hugh fitzcairn#roger daltrey#methos#peter wingfield#homework meme#tv#90s#1990s#nostolgia#highlander#tv show#highlander tv show

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

Send me a character I've mentioned in my tags, and I'll tell you some of my headcanons for them.

#(This means if you reblog this to mention characters you want to yap about in *your* tags.)#ask games#ask game#erron black#skarlet#nitara#reiko#mortal kombat#liv mckenzie#vince schneider#wes hicks#wayne bailey#richie kirsch#quinn bailey#ethan landry#amber freeman#scream 5#scream 6#envy adams#todd ingram#spvtw#spto#jason carver#stranger things#charles lee ray#tiffany valentine#peter ray#elizabeth ray#chucky tv series#txt

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Walker royal family (main branch)

Here they are in their glory! The main family of the Mystique tales and Great Wizards Au! (Excuse the shitty handwriting 😞)

Some lore and informations under the cut~.

Ramilia and Lavi:

—They’re three years apart, Ramilia being born on October 10th, 1594. And Lavi was born on July 29th, 1591. (This is all based on the anime timeline that Acier had died a few days or hours after Noelle was born in 1619)

—their marriage was arranged, Ramilia first met Lavi on the day she turned 14 (with Lavi being 17 at the time).

—they both come from royal families, Lavi married into Ramilia’s family. He originally was born in house Hart, he was the oldest of three (having two younger sisters, Minerva and Emma. Minerva is Mimosa and Kirsch’s mother, Making them Noelle’s paternal cousins instead of maternal).

—Ramilia is the second oldest, she has one older sister, Elizabeth. and a younger twin brother, Alexander. And a younger sister who died at 12 when Ramilia was 16, Wendy. And the youngest is Raymond, who is 23 years younger than Ramilia.

—The Walker family originally inhabited the land five centuries prior to the Silvamillion family coming to the land, the Silvamillions forced the Walker family (who were lead by the 18th great wizard at the time) to retreat to a place known as the back lands (known as the forsaken realm nowadays).

—in the late 1120’s the Walker family and the Silvamillion family signed a peace treaty. And in 1140, the clover kingdom rose with the Silvamillion family and the Walker family as the rulers.

—the Hart Family was a branch that originated from the Vermillion family back in the late 1290’s because of a disease that spread around their family that caused due to severe incest causing the members’ immune systems to fail immediately, causing the Vermillion’s to almost go extinct. So they split the Earth mages (who are known now as The Hart royal Family, keep in mind not all of them are Earth mages due to different bloodlines integrating into the Hart bloodline, Lavi’s father had fire magic hence the reason why he’s a fire mage, but his sisters have earth magic) and the Fire mages (the Vermillions, obviously the plant Vermillion’s are the exception) and forced these two families to marry out of each other, and now almost 300 years later there is not even a small percentage of incest found in the current families bloodline since the Vermillions/most royals marry from Nobility nowadays (Lavi and Minerva are the only exception today)

—the reason that made house Hart give up the man who could’ve been the next house head, was because Lavi was a failure in their eyes. He couldn’t control his magic at all, it constantly ran wild and in his first days as a magic knight he would accidentally injure his squadmates, eventually it caused the burn scar on his right eye (Also royals see scars as a sign of weakness that’s why Lavi’s family were so eager to get rid of him), and was everything a royal shouldn’t be, empathetic, caring and loyal towards the people and wanted to change the way the royal families treated their citizens of lower classes.

—when Lavi tells Ramilia this is the reason, Ramilia makes it her mission to make it possible for him to do these things he envisioned. Being the Great Wizard made it easy for her to make his ideals a reality.

—they got married the following year as soon as Ramilia turned 15 (the consent age at that time), and Lavi had already been 18 for a while (before anyone comes at me, Lavi never went near Ramilia at all. He despised the idea of being married to a barely legal child, so they never consummated their marriage until Ramilia was 23 and Lavi was 26, they had the twins at 25 and 28) the main reason that they were arranged was due to the lack of birth of any true blood successors in the last 47 years prior to Ramilia’s birth.

—Ramilia’s birth was hailed a miracle. as her Grandmother, Elizabeth the 18th who reigned as the 48th Great Wizard was the last true blood successor for nearly fifty years.

—the Walkers during this time had found out that Chaos (the power that gives them the right to use the chosen successor’s magic “Dark matter” and gives the successors the Black Blood that Walker Family is known by in the Clover Kingdom). Had chosen to abandon them during the period between the 48th and the 49th, thus causing the period to be referred to as the “the shameful era”.

—and now you’re wondering, if Ramilia is the 50th, and Noelle’s the 51st, who was the 49th then? Simple, a woman named Marlin Atkins, she was the first and only outsider to be called The Great Wizard. (She has her own lore, we’re not getting into that here)

—Ramilia came from an abusive Mother and a cowardly father who couldn’t do anything about the way his wife had been treating his children.

—Lavi is the current captain of the Crimson Lions, Fuegoleon is his Vice-Captain.

—the Great wizard is actually considered the real ruler of clover, they put a king just for show and for the sake of the peace treaty. So you can basically say Ramilia is the Clover Queen, although she hates it.

—the wizard kings are considered the second righthand men to the Great Wizards, focusing on the military power and external country affairs, and being in charge of enlisting/disbanding magic knight squads. While the great wizards concern themselves with the internal country affairs and keeping the people in check.

—there is a succession elemental cycle, it starts with, Wind-water-earth-fire. And along with it, Comes the secondary magic, Dark matter.

—Dark matter is basically a dark substance that changes depending on the element, for example, Ramilia was born in the wind cycle, the easiest to control and the most lightest element, it gives Dark matter the opposite qualities, When Ramilia uses it she gets covered by a heavy dark armour which causes her attacks when using it along with her wind magic to deliver more damage.

—the Great Wizards have the same elements as their zodiac signs, Ramilia is a Libra which is an air sign, and she possesses wind magic as her cycle element.

—each Great Wizard has a name for their era and generation. Marlin was “The shameful” Era/Generation. Ramilia’s Era is referred to as “The Mystique” Era/Generation.

Noah and Noelle:

—They’re twins, it is common for twins to be born in the Walker family (Ramilia’s parents were both twins so it made sense why she ended up having twins)

—Noah is the oldest by 10 minutes. And he takes it seriously.

—They’re born on November 15th (obviously), 1619.

—Noelle and Noah are the opposites of each other, where Noelle is friendly and lovable, Noah is a pessimist and uncaring, you can hardly get a reaction out of him for anything, the only person able to get a reaction out of him is Noelle and most of the time it’s negative ones, like yelling at her for being reckless or being a bad example for their younger siblings.

—the twins were an accident, Lavi hadn’t meant to get Ramilia pregnant as they have been busy raising Ray and agreed to never have children and hoped that one of Ramilia’s siblings would be the one to give her a successor to the Great Wizard title, when they found out that Ramilia was pregnant she had already been to far along to abort the babies, so they had them.

—it was a pleasant surprise to Ramilia and Marlin when Noelle was born with the black blood, and it made Ramilia’s problems a bit easier.

—since she’s the next Great Wizard, Noelle wears a certain coloured earring on her left ear, it is a tradition in the Walker family to wear them to indicate your status within the family, so the color of Noelle’s earring indicates that she’s the next/current Great Wizard. Ramilia wears the same coloured earring in the same spot.

—Noah also wears an earring in the same spot that Noelle and his mother do, this indicates that he’s the oldest and the next/current house head, Ramilia wears the same coloured earring in a different spot. And he has another ear piercing that is traditional for males of the Walker family to wear.

—generally, the Walker Family favours the females rather than the males, so unless the firstborn is a boy the position of house head tends to go to the deserving/stronger females of the family.

—Noah has wind magic, While Noelle possesses water magic since she was born in the Water cycle.

—Noelle’s Era has yet to be named, But Ramilia predicts that it’s gonna be called “The Valkyrie” Era. (No, this is totally not because of Noelle’s Valkyrie armour).

—Noah Joins the family squad, The White Tigers (are you really surprised that I have them in this Au as well 🌚). While Noelle is sent by her parents to the Black Bulls.

Ava:

—Ava was born on February 12th, 1622. She was an accident like the twins.

—she has fire magic, and is the only one so far between her siblings to inherit their father’s magic.

—she’s similar to Mimosa in personality.

—She’s close to Noelle. Ramilia used to joke that Ava would dye her hair if she could to look like Noelle, she admires her sister so much and brags about how she’s going to follow in their mother’s foot steps and become an even amazing Great wizard than their mother.

—Albert gets on her nerves constantly.

—she has expressed her wishes to Join the Black bulls to be with Noelle, to which Noelle forbade her from for obvious reasons.

—she’s the best one in her siblings with magic control, she was able to do a full spell at 9 despite not possessing a Grimoire at all.

—she’s a daddy’s girl, actually both Noelle and Ava are daddy’s girls. Lavi adores his daughters too much.

—she wears an earring like Noelle, but it’s magenta while Noelle’s earring is purple, to indicate she’s a “spare” successor.

Albert:

—Albert was born on august 10th, 1624. Unlike his siblings, Albert was planned.

—basically Ramilia and Lavi went through some serious shit and realized how much they loved each other, and how they wanted to leave the evidences of their love and life behind, hence why Albert happened.

—he has wind magic.

—Albert is Ramilia’s favourite, he was the easiest pregnancy and the easiest delivery and the easiest baby to deal with.

—due to this, Albert becomes a huge mama’s boy, but Ramilia knows when to step back and dial down on spoiling him so that Albert doesn’t become a brat.

—he’s the one with the most resemblance to his father, Ramilia jokes that Albert is a carbon Copy of a younger Lavi, which he is.

—he’s a known prankster, he gets on Ava’s nerves a lot and gets in severe trouble for it. (He’s the main reason Lavi started graying this early, besides Mereoleona obviously). The only person he never pranks is Mimosa because he’s terrified of her and finds his cousin scary, no one believes him when he says this, because no one can imagine sweet and lovely Mimosa as someone scary.

—he used to be the youngest and enjoyed the attention he constantly got. Then Nolan was born and the attention shifted from him which caused him to start acting more appropriately nowadays.

—just like Ava, he’s super close to Noelle. When he was a bit younger he used to sleep with Noelle in her bed when she’d let him, and they would stay up at times way past their bed time just talking about magic theories and old stories of the previous Great Wizards.

—he wants to join the crimson lions to be near his father, But Ramilia is hell bent on sending him to the Golden Dawn since Mimosa would keep him well behaved.

Nolan:

—the baby! He shares the same birthdate as the twins. He was born on November 15th, 1634. Which was Noelle and Noah’s 15th birthday.

—he was an accident, Ramilia freaked out on Lavi when she found out. And Lavi freaked out too because at that point they were both 39 and 42 and had no desire to raise a child all over again. But they had Nolan in the end and it all turned out good.

#black clover#noelle silva#my oc’s#BcOC: Ramilia Walker#BcOC: Lavi#BcOC: Noah#BcOC: Ava#BcOC: Albert#BcOC: Nolan#My art; Mystique tales and Great Wizards#mystique tales and great wizards

1 note

·

View note

Text

A federal judge struck down a portion of New Jersey's so-called "sanctuary" law blocking private migrant detention contracts with the Biden administration's federal agencies.

In August 2021, Democrat Gov. Phil Murphy enacted Assembly Bill 5207, prohibiting New Jersey, its political subdivisions and private entities "from prospectively contracting to own or operate any facility that detains individuals for violating civil immigration laws."

At the time of the bill’s passage, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and the division of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) responsible for detaining individuals for civil immigration violations was using four detention facilities in New Jersey, but as the legislation became law, three of those four facilities stopped housing detainees on ICE’s behalf. Now, just one remains – the Elizabeth Detention Center (EDC). Its private operator CoreCivic, Inc.’s federal contract was set to expire on Aug. 31, and afterward, the New Jersey law would have prevented the private contractor from renewing it.

In a Tuesday ruling, U.S. District Court Judge Robert Kirsch sided with CoreCivic’s lawsuit filed earlier this year, ruling the legislation unconstitutional.

"A state law that wholesale deprives the federal government of its chosen method of detaining individuals for violating federal law cannot survive Supremacy Clause scrutiny," the judge wrote. "[The law] would impose on the United States an intolerable choice between either releasing federal detainees or carrying out detention in an entirely novel way."

ADAMS SAYS HOCHUL 'WRONG' ON NYC MIGRANT CRISIS, URGES 'REAL LEADERSHIP' TO PUSH ASYLUM SEEKERS ACROSS STATE

Biden administration attorneys argued that if New Jersey's neighboring states passed laws similar to AB 5207, "ICE will be unable to detain some (or perhaps many) noncitizens who are public safety or national security risks." The United States claimed "a drastic decrease in ICE'S ability to contract for detention facilities would also result in massively increased costs in terms of both transportation needs and the hiring of more officers to ensure that noncitizens are safely transported to distant facilities."

The administration also asserted that attempting to comply with AB 5207 by building and operating its own detention facility in New Jersey is "not a practical or legal possibility," because constructing and opening a new facility would be more expensive and time-consuming than entering into a contract with a private company or public entity for an existing facility.

The Elizabeth center is the only facility that houses ICE detainees within 60 miles of New York City. As of mid-June 2023, the EDC held approximately 285 detainees.

The federal government has been housing immigration detainees in New Jersey since at least 1986.

If the state law forces ICE to house detainees outside of New Jersey, ICE would likely need to initiate "a competitive solicitation process for new private contracts in other States to replace the lost capacity in New Jersey," which "wouldn't be available for some time," Kirsch's ruling says. Biden administration attorneys cite the EDC's proximity to two international airports — the Newark Liberty International Airport and the JFK International Airport — that make EDC crucial to ICE'S operations, as well as the operations of other federal agencies.

DHS CALLS FOR IMPROVEMENTS TO NYC’S MIGRANT CRISIS OPERATIONS AS ADAMS PUSHES BACK

"While ICE has discretion to release certain noncitizens pending their removal proceedings if they are not flight risks and do not pose a public-security threat, ICE is required to detain categories of noncitizens who are subject to mandatory detention under the immigration laws or those who pose risk to public safety," the opinion says. "Congress has likewise granted DHS discretion over the manner in which it detains individuals for civil immigration violations."

The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals shot down a similar California law in September 2022.

Murphy’s office told Politico that the New Jersey Attorney General’s office will plan an appeal. The state maintains "private detention facilities threaten the public health and safety of New Jerseyans, including when used for immigration purposes."

Last week, all but one of New Jersey’s Democrat congressional delegation penned a letter to U.S. Attorney General Merrick Garland demanding the Department of Justice rescind its statement of interest in the CoreCivic lawsuit opposing the state law. The letter cites reports from detainees and legal advocates about "inhuman conditions" at the Elizabeth facility, including lack of proper air quality, sanitation violations, overcrowding, inadequate media and mental health care and alleged "incidents of retaliation and abusive treatment by guards and staff." They also cited "extensive complaints, lawsuits, protests and calls for action" against the facility.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

(ray) welcome to london, VANESSA SHELLY! did anyone ever tell you that you look just like ELIZABETH LAIL? well, no matter, we hear that you are 31 and working as a POLICE OFFICER. we also hear that you currently HAVE your memories from FIVE NIGHTS AT FREDDY’S and have a tendency to be PROTECTIVE as well as SNARKY.

(ray) welcome to london, AMBER FREEMAN! did anyone ever tell you that you look just like MIKEY MADISON? well, no matter, we hear that you are 24 and working as a MOVIE THEATRE EMPLOYEE. we also hear that you currently HAVE your memories from SCREAM and have a tendency to be THRILL-SEEKING as well as VIOLENT.

(ray) welcome to london, ETHAN KIRSCH LANDRY! did anyone ever tell you that you look just like JACK CHAMPION? well, no matter, we hear that you are 20 and working as an ART STUDENT. we also hear that you currently HAVE your memories from SCREAM and have a tendency to be INTELLIGENT as well as AWKWARD. (( please can i switch out lady from lady & tramp as i’ve lost museee. thanks !! ))

— WELCOME TO LONDON, vanessa shelly, amber freeman & ethan landry! you look very familiar, do we know you from somewhere? anyways, take your time settling in because whether you want to or not, it looks like you’re going to be living here for awhile! // welcome ray, please be sure to follow our checklist here. welcome to the group!

#submission#multifandom rp#fandom rp#city rpg#au rpg#town rpg#mumu rp#fandom rpg#scream rp#fnaf rp#vanessa shelly#amber freeman#ethan landry

0 notes

Text

by Adam Kirsch

In Elif Batuman’s 2022 novel Either/Or, the narrator, Selin, goes to her college library to look for Prozac Nation, the 1994 memoir by Elizabeth Wurtzel. Both of Harvard’s copies are checked out, so instead she reads reviews of the book, including Michiko Kakutani’s in the New York Times, which Batuman quotes:

“Ms. Wurtzel’s self-important whining” made Ms. Kakutani “want to shake the author, and remind her that there are far worse fates than growing up during the 70’s in New York and going to Harvard.”

It’s a typically canny moment in a novel that strives to seem artless. Batuman clearly recognizes that every criticism of Wurtzel’s bestseller—narcissism, privilege, triviality—could be applied to Either/Or and its predecessor, The Idiot, right down to the authors’ shared Harvard pedigree. Yet her protagonist resists the identification, in large part because she doesn’t see herself as Wurtzel’s contemporary. Wurtzel was born in 1967 and Batuman in 1977. This makes both of them members of Generation X, which includes those born between 1965 and 1980. But Selin insists that the ten-year gap matters: “Generation X: that was the people who were going around being alternative when I was in middle school.”

I was born in 1976, and the closer we products of the Seventies get to fifty, the clearer it becomes to me that Batuman is right about the divide—especially when it comes to literature. In pop culture, the Gen X canon had been firmly established by the mid-Nineties: Nirvana’s Nevermind appeared in 1991, the movie Reality Bites in 1994, Alanis Morissette’s Jagged Little Pill in 1995. Douglas Coupland’s book Generation X, which popularized the term, was published in 1991. And the novel that defined the literary generation, Infinite Jest, was published in 1996, when David Foster Wallace was about to turn thirty-four—technically making him a baby boomer.

Batuman was a college sophomore in 1996, presumably experiencing many of the things that happen to Selin in Either/Or. But by the time she began to fictionalize those events twenty years later, she joined a group of writers who defined themselves, ethically and aesthetically, in opposition to the older representatives of Generation X. For all their literary and biographical differences, writers like Nicole Krauss, Teju Cole, Sheila Heti, Ben Lerner, and Tao Lin share some basic assumptions and aversions—including a deep skepticism toward anyone who claims to speak for a generation, or for any entity larger than the self.

That skepticism is apparent in the title of Zadie Smith’s new novel, The Fraud. Smith’s precocious success—her first book, White Teeth, was published in 2000, when she was twenty-four—can make it easy to think of her as a contemporary of Wallace and Wurtzel. In fact she was born in 1975, two years before Batuman, and her sensibility as a writer is connected to her generational predicament.

Smith’s latest book is, most obviously, a response to the paradoxical populism of the late 2010s, in which the grievances of “ordinary people” found champions in elite figures such as Donald Trump and Boris Johnson. Rather than write about current events, however, Smith has elected to refract them into a story about the Tichborne case, a now-forgotten episode that convulsed Victorian England in the 1870s.

In particular, Smith is interested in how the case challenges the views of her protagonist, Eliza Touchet. Eliza is a woman with the sharp judgment and keen perceptions of a novelist, though her era has deprived her of the opportunity to exercise those gifts. Her surname—pronounced in the French style, touché—evokes her taste for intellectual combat. But she has spent her life in a supportive role, serving variously as housekeeper and bedmate to her cousin William Harrison Ainsworth, a man of letters who churns out mediocre historical romances by the yard. (Like most of the novel’s characters, Ainsworth and Touchet are based on real-life historical figures.)

Now middle-aged, Eliza finds herself drawn into public life by the Tichborne saga, which has divided the nation and her household as bitterly as any of today’s political controversies. Like all good celebrity trials, the case had many supporting players and intricate subplots, but at heart it was a question of identity: Was the man known as “the Claimant” really Roger Tichborne, an aristocrat believed to have died in a shipwreck some fifteen years earlier? Or was he Arthur Orton, a cockney butcher who had emigrated to Australia, caught wind of the reward on offer from Roger’s grief-stricken mother, and seized the chance of a lifetime? In the end, a jury decided that he was Orton, and instead of inheriting a country estate he wound up in a jail cell. What fascinates Smith, though, is the way the Tichborne case became a political cause, energizing a movement that took justice for “Sir Roger” to be in some way related to justice for the common man.

Eliza is a right-minded progressive who was active in the abolitionist movement in the 1830s. Proud of her judgment, she sees many problems with the Claimant’s story and finds it incredible that anyone could believe him. To her dismay, however, she lives with someone who does. William’s new wife, Sarah, formerly his servant, sees the Claimant as a victim of the same establishment that lorded over her own working-class family. The more she is informed of the problems with the Claimant’s argument, the more obdurate she becomes: “HE AIN’T CALLED ARTHUR ORTON IS HE,” she yells, “THEM WHO SAY HE’S ORTON ARE LYING.”

What Smith is dramatizing, of course, is the experience of so many liberal intellectuals over the past decade who had believed themselves to be on the side of “the people” only to find that, whether the issue was Brexit or Trump or COVID-19 protocols, the people were unwilling to heed their guidance, and in fact loathed them for it. It is in order to get to the bottom of this phenomenon that Eliza keeps attending the Tichborne trial, in much the same spirit that many liberal journalists reported from Trump rallies. Things get even more complicated when she befriends a witness for the defense, Mr. Bogle, who is among the Claimant’s main supporters even though he began his life as a slave on a Jamaica plantation managed by Edward Tichborne, the Claimant’s supposed father.

Though much of the novel deals with the case and the history of slavery in Britain’s Caribbean colonies, it is first and foremost the story of Eliza Touchet, and how her exposure to the trial alters her sense of the world and of herself. “The purpose of life was to keep one’s mind open,” she reflects, and it is this ability to see things from another perspective that makes her a novelist manqué.

Open-mindedness, even to the point of moral ambiguity, is one of the chief values Smith shares with her literary contemporaries. These writers grew up during a period of heightened tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union, then took their first steps toward adult consciousness just as the Cold War concluded. They came of age in the brief period that Francis Fukuyama called “the end of history.”

Fukuyama’s description, famously premature though it was, still captures something crucial about the context in which the children of the Seventies began to think and write. While the fall of Communism in Eastern Europe is sometimes remembered as the “Revolutions of 1989,” the mood it created in the West was hardly revolutionary. After 1989, there was little of the “bliss was it in that dawn to be alive” sentiment that had animated Wordsworth during the French Revolution. Instead, the ambient sense that history was moving steadily in the right direction encouraged writers to see politics as less urgent, and less morally serious, than inward experience.

In the fiction that defined the pre-9/11 era, political phenomena tended to assume cartoon form. Wallace’s Infinite Jest features an organization of Quebecois separatists called Les Assassins des Fauteuils Rollents—that is, the Wheelchair Assassins. In Smith’s White Teeth, one of the main characters joins a militant group named KEVIN, for Keepers of the Eternal and Victorious Islamic Nation. The attacks on the Twin Towers and the war on terror would put an end to jokes like these, but for a decade or so it was possible to see ideological extremism as a relic fit for spoofing—as with KGB Bar, a popular New York literary venue that opened in 1993.

For the young writers of that era, the most important battles were not being fought abroad but at home, and within themselves. Their enemies were the forces of cynicism and indifference that Wallace depicted in Infinite Jest, set in a near-future America stupefied by consumerism, mass entertainment, and addictive substances. The great balancing act of Wallace’s fiction was to truthfully represent this stupor while holding open the possibility that one could recover from it, the way the residents of the novel’s Ennet House manage to recover from their addictions. This dialectical mission is responsible for the spiraling self-consciousness that is the most distinctive (and, to some readers, the most annoying) aspect of his writing.

Dave Eggers set himself an analogous challenge in his 2000 memoir A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius. Writing about a childhood tragedy—the nearly simultaneous deaths from cancer of his mother and father, which left the young Eggers with custody of his eight-year-old brother—he aimed to do full justice to his despair while still insisting on the validity of hope. “This did not happen to us for naught, I can assure you,” he writes,

there is no logic to that, there is logic only in assuming that we suffered for a reason. Just give us our due. I am bursting with the hopes of a generation, their hopes surge through me, threaten to burst my hardened heart!

By the end of the millennium, this was the familiar voice of Generation X. Loquacious and self-involved, its ironic grandiosity barely concealed a sincere grandiosity about its moral mission, which was to defeat despair and foster genuine human connection. Jonathan Franzen, Wallace’s realist rival, titled a book of essays How to Be Alone, and for these writers, loneliness was the great problem that literature was created to solve. “If writing was the medium of communication within the community of childhood, it makes sense that when writers grow up they continue to find writing vital to their sense of connectedness,” Franzen wrote in his much-discussed essay “Perchance to Dream,” published in these pages in 1996. Eggers seems to have taken this idea literally, creating a nonprofit, 826 Valencia, that advertises writing mentorship for underserved students as a way of “building community” and rectifying inequality.

If sincerity and connection were the greatest virtues for these writers, the greatest sin was “snark.” That word gained literary currency thanks to a manifesto by Heidi Julavits in the first issue of The Believer, the magazine she co-founded in 2003 with the novelist Vendela Vida (Eggers’s wife) and the writer Ed Park. The title of the essay—“Rejoice! Believe! Be Strong and Read Hard!”—like the title of the magazine, insisted that literature was an essentially moral enterprise, a matter of goodness, courage, and love. To demur from this vision was to reveal a smallness of soul that Julavits called snark: “wit for wit’s sake—or, hostility for hostility’s sake,” a “hostile, knowing, bitter tone of contempt.” For Kafka, a book was an axe for the frozen sea within; for the older cohort of Gen X writers, it was more like a hacksaw to cut through the barred cell of cynicism.

This was the environment—quiescent in politics, self-consciously sincere in literature—in which Smith and her contemporaries came of age. Just as they started to publish their first books, however, the stopped clock of history resumed with a vengeance. It is unnecessary to list the series of political and geopolitical shocks that have occurred since 2000. For the millennial generation, adulthood has been defined by apocalyptic fears, political frenzy, and glimpses of utopia, whether in Chicago’s Grant Park on election night 2008 or in New York’s Zuccotti Park during Occupy Wall Street in 2011.

The children of the Seventies tend to feel out of place in this new world. It’s not that they naïvely looked forward to a future of peace and harmony and are offended to find that it has not materialized. It is rather that their literary gaze was fixed within at an early age, and they continue to believe that the most authentic way to write about history is as the deteriorating climate through which the self moves.

The self, meanwhile, they approach with mistrust—a reaction against the heart-on-sleeve sincerity of their elders. Many of them have turned to autofiction, a genre which is often criticized as narcissistic—a way of shrinking the world to fit into the four walls of the writer’s room. In fact, it has served these writers as an antidote to the grandiosity of memoir, which tends to falsify in the direction of self-flattery—as this generation learned from the spectacular implosion of James Frey’s 2003 bestseller, A Million Little Pieces. By admitting from the outset that it is not telling the truth about the author’s life, autofiction makes it possible to emphasize the moral ambiguities that memoir has to apologize for or hide. That makes it useful for writers who are not in search of goodness, neither within themselves nor in political movements.

For Sheila Heti, this resistance to goodness takes the form of artistic introspection, which busier people tend to judge as selfish and idle. In How Should a Person Be?, from 2010, a character named Sheila has dinner with a young theater director named Ben, who has just returned with a friend from South Africa. “It was just such a crushing awakening of the colossal injustice of the way our world works economically,” he says of their trip, that he now wonders whether his work as a theater director—“a very narcissistic activity”—is morally justifiable. Yet nothing could be more narcissistic, in Heti’s telling, than such moral preening, and Sheila instinctively resists it. “They are so serious. They lectured me about my lack of morality,” she complains. She loathes the idea of having “to wear on the outside one’s curiosity, one’s pity, one’s guilt,” when art is concerned with what happens inside, which can only be observed with effort and in private. “It’s time to stop asking questions of other people,” she tells herself. “It is time to just go into a cocoon and spin your soul.”

Teju Cole’s 2011 novel Open City offers a more ambivalent version of the same idea. Julius, the narrator, can’t justify his aesthetic self-absorption on the grounds that he is an artist, as Sheila does, since he is a psychiatrist. It’s an ironic choice of profession for a man we come to know as guarded and aloof. Cole builds a portrait of Julius through his daily interactions with other people, like the taxi driver whose cab he enters gruffly. “The way you came into my car without saying hello, that was bad,” the driver rebukes him. “Hey, I’m African just like you, why you do this?” Julius apologizes for this small breach of solidarity, but insincerely: “I wasn’t sorry at all. I was in no mood for people who tried to lay claims on me.”

Indeed, for most of the novel he is alone, meditating in Sebaldian fashion on the atrocities of history as he takes long walks through Manhattan. When, during a trip to Brussels, he meets a man who wants to intervene in history—Farouq, a young Moroccan intellectual who declares that “America is a version of Al-Qaeda”—Julius is decidedly unimpressed:

There was something powerful about him, a seething intelligence, something that wanted to believe itself indomitable. But he was one of the thwarted ones. His script would stay in proportion.

Open City can’t be said to endorse Julius’s aesthetic solipsism. On the contrary, the last chapter finds him trapped on a fire escape outside Carnegie Hall in the rain, a striking symbol of a man isolated by culture. Just moments before, he had been united with the rest of the audience in Mahlerian rapture; now, he reflects, “my fellow concertgoers went about their lives oblivious to my plight,” as he tries to avoid slipping and falling to his death. The scene is Cole’s acknowledgment that aesthetic consciousness remains passive and solipsistic even when experienced in common, and that danger demands a different kind of solidarity—one that is active, ethical, even political. Yet Cole conjures Julius’s aristocratic fatalism in such intimate detail that the “Rejoice! Believe!” approach—to literature, and to life—can only appear childish.

Writers of this cohort do sometimes try to imagine a better world, but they tend to do so in terms that are metaphysical rather than political, moving at one bound from the fallen present to some kind of messianic future. In her 2022 novel Pure Colour, Heti tells the story of a woman named Mira whose grief over her father’s death prompts her to speculate about what Judaism calls the world to come. In Heti’s vision, this is not a place to which the soul repairs after death, nor is it some kind of revolutionary political arrangement; rather, it is an entirely new world that God will one day create to replace the one we live in, which she calls “the first draft of existence.”

The hardest thing to accept, for Heti’s protagonist, is that the end of our world will mean the disappearance of art. “Art would never leave us like a father dying,” Mira says. “In a way, it would always remain.” But over the course of Pure Colour, she comes to accept that even art is transitory. In a profoundly self-accusing passage, she concludes that a better world might even require the disappearance of art, since

art is preserved on hearts of ice. It is only those with icebox hearts and icebox hands who have the coldness of soul equal to the task of keeping art fresh for the centuries, preserved in the freezer of their hearts and minds.

Tao Lin’s unnerving, affectless autofiction leaves a rather different impression than Heti’s, and he has sometimes been identified as a voice from the next generation, the millennials. But his 2021 novel Leave Society shows him thinking along similar lines as the children of the Seventies. In Taipei, from 2013, Lin’s alter ego is named Paul, and he spends most of the novel joylessly eating in restaurants and taking mood-altering drugs. In Leave Society he is named Li, but he is recognizably the same person, perched on a knife-edge between extreme sensitivity and neurotic withdrawal. In the interim, he has decided that the cure for his troubles, and the world’s, lies in purging the body of the toxins that infiltrate it from every direction.

Like Heti, Lin anticipates a great erasure. All of recorded history, he writes, has been merely a “brief, fallible transition . . . from matter into the imagination.” Sometime soon we will emerge into a universe that bears no resemblance to the one we know. Writers, Lin concludes, participate in this process not by working for social change but by reforming the self. “Li disliked trying to change others,” Lin writes, and believed that “people who are concerned about evil and injustice in the world should begin the campaign against those things at their nearest source—themselves.”

One way or another, writers in this cohort all acknowledge the same injunction—even the ones who struggle against it. In his new book of poems, The Lights, Ben Lerner strives to elaborate an idea of redemption that is both private and social:

I don’t know any songs, but won’t withdraw. I am dreaming

the pathetic dream of a pathos capable of redescription,

so that corporate personhood becomes more than legal fiction.

A dream in prose of poetry, a long dream of waking.

The dream of uniting the sophistication of art with the straightforwardness of justice also animates Lerner’s fiction, where it often takes the form of rueful comedy. In 10:04, the narrator cooks dinner for an Occupy Wall Street protester, but when asked how often he has been to Zuccotti Park, he dodges the question. His activism is limited to cooking, which he pompously describes as a way of being “a producer and not a consumer alone of those substances necessary for sustenance and growth within my immediate community.” That the dream never becomes more than a dream betrays Lerner’s similarity to Lin, Heti, and Cole, who frankly acknowledge the hiatus between art and justice, though without celebrating it.

Zadie Smith has always been too deeply rooted in the social comedy of the English novel to embrace autofiction, yet she also registers this disconnect, as can be seen in the way her influences have shifted over time. When it was first published, White Teeth was compared to Infinite Jest and Don DeLillo’s Underworld as a work of what James Wood called “hysterical realism.” The book’s arch humor, proliferating plot, and penchant for exaggeration owe much to the author Wood identified as the “parent” of that genre: Charles Dickens.

When Smith says that a woman “needed no bra—she was independent, even of gravity,” she is borrowing Dickens’s technique of making characters so intensely themselves that their essence saturates everything around them—as when he writes of the nouveau riche Veneerings, in Our Mutual Friend, that “their carriage was new, their harness was new, their horses were new, their pictures were new, they themselves were new.” Dickens is a guest star in The Fraud, appearing at several of William Ainsworth’s dinner parties, and the news of his death prompts Eliza Touchet to offer an apt tribute: “She knew she lived in an age of things . . . and Charles had been the poet of things.”

But Dickens, who at another point in the novel is gently disparaged for his moralizing “sermons,” is no longer the presiding genius of Smith’s fiction. (Smith wrote in a recent essay that her first principle in taking up the historical novel was “no Dickens,” and she expressed a wry disappointment that he had forced his way into the proceedings.) Her 2005 novel, On Beauty, was a reimagining of E. M. Forster’s Howards End, and while her style has continued to evolve from book to book, Forster’s influence has been clear ever since, in everything from her preference for short chapters to her belief in “keep[ing] one’s mind open.”

Smith’s affinity for Forster owes something to their analogous historical situations. An Edwardian liberal who lived into the age of fascism and communism, Forster defended his values—“tolerance, good temper and sympathy,” as he put it in the 1939 essay “What I Believe”—with something of a guilty conscience, recognizing that the militant younger generation regarded them as “bourgeois luxuries.”

At the end of The Fraud, Eliza encounters Mr. Bogle’s son Henry, who has grown disgusted with his father’s quietism and become a political radical. He reproaches her for being more interested in understanding injustice than in doing something about it, proclaiming:

By God, don’t you see that what young men hunger for today is not “improvement” or “charity” or any of the watchwords of your Ladies’ Societies. They hunger for truth! For truth itself! For justice!

This certainty and urgency is the opposite of keeping one’s mind open, and while Mrs. Touchet—and Smith—aren’t prepared to say that it is wrong, they are certain that it’s not for them: “This essential and daily battle of life he had described was one she could no more envisage living herself than she could imagine crossing the Atlantic Ocean in a hot air balloon.”

Whether they style themselves as humanists or aesthetes, realists or visionaries, the most powerful writers who were born in the Seventies share this basic aloofness. To the next generation, the millennials, their disengagement from the collective struggle may seem reprehensible. For me, as I suspect is the case for many readers my age, it is part of what makes them such reliable guides to understanding, if not the times we live in, then at least the disjunction between the times and the self that must try to negotiate them.

0 notes

Text

by Adam Kirsch

In Elif Batuman’s 2022 novel Either/Or, the narrator, Selin, goes to her college library to look for Prozac Nation, the 1994 memoir by Elizabeth Wurtzel. Both of Harvard’s copies are checked out, so instead she reads reviews of the book, including Michiko Kakutani’s in the New York Times, which Batuman quotes:

“Ms. Wurtzel’s self-important whining” made Ms. Kakutani “want to shake the author, and remind her that there are far worse fates than growing up during the 70’s in New York and going to Harvard.”

It’s a typically canny moment in a novel that strives to seem artless. Batuman clearly recognizes that every criticism of Wurtzel’s bestseller—narcissism, privilege, triviality—could be applied to Either/Or and its predecessor, The Idiot, right down to the authors’ shared Harvard pedigree. Yet her protagonist resists the identification, in large part because she doesn’t see herself as Wurtzel’s contemporary. Wurtzel was born in 1967 and Batuman in 1977. This makes both of them members of Generation X, which includes those born between 1965 and 1980. But Selin insists that the ten-year gap matters: “Generation X: that was the people who were going around being alternative when I was in middle school.”

I was born in 1976, and the closer we products of the Seventies get to fifty, the clearer it becomes to me that Batuman is right about the divide—especially when it comes to literature. In pop culture, the Gen X canon had been firmly established by the mid-Nineties: Nirvana’s Nevermind appeared in 1991, the movie Reality Bites in 1994, Alanis Morissette’s Jagged Little Pill in 1995. Douglas Coupland’s book Generation X, which popularized the term, was published in 1991. And the novel that defined the literary generation, Infinite Jest, was published in 1996, when David Foster Wallace was about to turn thirty-four—technically making him a baby boomer.

Batuman was a college sophomore in 1996, presumably experiencing many of the things that happen to Selin in Either/Or. But by the time she began to fictionalize those events twenty years later, she joined a group of writers who defined themselves, ethically and aesthetically, in opposition to the older representatives of Generation X. For all their literary and biographical differences, writers like Nicole Krauss, Teju Cole, Sheila Heti, Ben Lerner, and Tao Lin share some basic assumptions and aversions—including a deep skepticism toward anyone who claims to speak for a generation, or for any entity larger than the self.

That skepticism is apparent in the title of Zadie Smith’s new novel, The Fraud. Smith’s precocious success—her first book, White Teeth, was published in 2000, when she was twenty-four—can make it easy to think of her as a contemporary of Wallace and Wurtzel. In fact she was born in 1975, two years before Batuman, and her sensibility as a writer is connected to her generational predicament.

Smith’s latest book is, most obviously, a response to the paradoxical populism of the late 2010s, in which the grievances of “ordinary people” found champions in elite figures such as Donald Trump and Boris Johnson. Rather than write about current events, however, Smith has elected to refract them into a story about the Tichborne case, a now-forgotten episode that convulsed Victorian England in the 1870s.

In particular, Smith is interested in how the case challenges the views of her protagonist, Eliza Touchet. Eliza is a woman with the sharp judgment and keen perceptions of a novelist, though her era has deprived her of the opportunity to exercise those gifts. Her surname—pronounced in the French style, touché—evokes her taste for intellectual combat. But she has spent her life in a supportive role, serving variously as housekeeper and bedmate to her cousin William Harrison Ainsworth, a man of letters who churns out mediocre historical romances by the yard. (Like most of the novel’s characters, Ainsworth and Touchet are based on real-life historical figures.)

Now middle-aged, Eliza finds herself drawn into public life by the Tichborne saga, which has divided the nation and her household as bitterly as any of today’s political controversies. Like all good celebrity trials, the case had many supporting players and intricate subplots, but at heart it was a question of identity: Was the man known as “the Claimant” really Roger Tichborne, an aristocrat believed to have died in a shipwreck some fifteen years earlier? Or was he Arthur Orton, a cockney butcher who had emigrated to Australia, caught wind of the reward on offer from Roger’s grief-stricken mother, and seized the chance of a lifetime? In the end, a jury decided that he was Orton, and instead of inheriting a country estate he wound up in a jail cell. What fascinates Smith, though, is the way the Tichborne case became a political cause, energizing a movement that took justice for “Sir Roger” to be in some way related to justice for the common man.

Eliza is a right-minded progressive who was active in the abolitionist movement in the 1830s. Proud of her judgment, she sees many problems with the Claimant’s story and finds it incredible that anyone could believe him. To her dismay, however, she lives with someone who does. William’s new wife, Sarah, formerly his servant, sees the Claimant as a victim of the same establishment that lorded over her own working-class family. The more she is informed of the problems with the Claimant’s argument, the more obdurate she becomes: “HE AIN’T CALLED ARTHUR ORTON IS HE,” she yells, “THEM WHO SAY HE’S ORTON ARE LYING.”

What Smith is dramatizing, of course, is the experience of so many liberal intellectuals over the past decade who had believed themselves to be on the side of “the people” only to find that, whether the issue was Brexit or Trump or COVID-19 protocols, the people were unwilling to heed their guidance, and in fact loathed them for it. It is in order to get to the bottom of this phenomenon that Eliza keeps attending the Tichborne trial, in much the same spirit that many liberal journalists reported from Trump rallies. Things get even more complicated when she befriends a witness for the defense, Mr. Bogle, who is among the Claimant’s main supporters even though he began his life as a slave on a Jamaica plantation managed by Edward Tichborne, the Claimant’s supposed father.

Though much of the novel deals with the case and the history of slavery in Britain’s Caribbean colonies, it is first and foremost the story of Eliza Touchet, and how her exposure to the trial alters her sense of the world and of herself. “The purpose of life was to keep one’s mind open,” she reflects, and it is this ability to see things from another perspective that makes her a novelist manqué.

Open-mindedness, even to the point of moral ambiguity, is one of the chief values Smith shares with her literary contemporaries. These writers grew up during a period of heightened tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union, then took their first steps toward adult consciousness just as the Cold War concluded. They came of age in the brief period that Francis Fukuyama called “the end of history.”

Fukuyama’s description, famously premature though it was, still captures something crucial about the context in which the children of the Seventies began to think and write. While the fall of Communism in Eastern Europe is sometimes remembered as the “Revolutions of 1989,” the mood it created in the West was hardly revolutionary. After 1989, there was little of the “bliss was it in that dawn to be alive” sentiment that had animated Wordsworth during the French Revolution. Instead, the ambient sense that history was moving steadily in the right direction encouraged writers to see politics as less urgent, and less morally serious, than inward experience.

In the fiction that defined the pre-9/11 era, political phenomena tended to assume cartoon form. Wallace’s Infinite Jest features an organization of Quebecois separatists called Les Assassins des Fauteuils Rollents—that is, the Wheelchair Assassins. In Smith’s White Teeth, one of the main characters joins a militant group named KEVIN, for Keepers of the Eternal and Victorious Islamic Nation. The attacks on the Twin Towers and the war on terror would put an end to jokes like these, but for a decade or so it was possible to see ideological extremism as a relic fit for spoofing—as with KGB Bar, a popular New York literary venue that opened in 1993.

For the young writers of that era, the most important battles were not being fought abroad but at home, and within themselves. Their enemies were the forces of cynicism and indifference that Wallace depicted in Infinite Jest, set in a near-future America stupefied by consumerism, mass entertainment, and addictive substances. The great balancing act of Wallace’s fiction was to truthfully represent this stupor while holding open the possibility that one could recover from it, the way the residents of the novel’s Ennet House manage to recover from their addictions. This dialectical mission is responsible for the spiraling self-consciousness that is the most distinctive (and, to some readers, the most annoying) aspect of his writing.

Dave Eggers set himself an analogous challenge in his 2000 memoir A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius. Writing about a childhood tragedy—the nearly simultaneous deaths from cancer of his mother and father, which left the young Eggers with custody of his eight-year-old brother—he aimed to do full justice to his despair while still insisting on the validity of hope. “This did not happen to us for naught, I can assure you,” he writes,

there is no logic to that, there is logic only in assuming that we suffered for a reason. Just give us our due. I am bursting with the hopes of a generation, their hopes surge through me, threaten to burst my hardened heart!

By the end of the millennium, this was the familiar voice of Generation X. Loquacious and self-involved, its ironic grandiosity barely concealed a sincere grandiosity about its moral mission, which was to defeat despair and foster genuine human connection. Jonathan Franzen, Wallace’s realist rival, titled a book of essays How to Be Alone, and for these writers, loneliness was the great problem that literature was created to solve. “If writing was the medium of communication within the community of childhood, it makes sense that when writers grow up they continue to find writing vital to their sense of connectedness,” Franzen wrote in his much-discussed essay “Perchance to Dream,” published in these pages in 1996. Eggers seems to have taken this idea literally, creating a nonprofit, 826 Valencia, that advertises writing mentorship for underserved students as a way of “building community” and rectifying inequality.

If sincerity and connection were the greatest virtues for these writers, the greatest sin was “snark.” That word gained literary currency thanks to a manifesto by Heidi Julavits in the first issue of The Believer, the magazine she co-founded in 2003 with the novelist Vendela Vida (Eggers’s wife) and the writer Ed Park. The title of the essay—“Rejoice! Believe! Be Strong and Read Hard!”—like the title of the magazine, insisted that literature was an essentially moral enterprise, a matter of goodness, courage, and love. To demur from this vision was to reveal a smallness of soul that Julavits called snark: “wit for wit’s sake—or, hostility for hostility’s sake,” a “hostile, knowing, bitter tone of contempt.” For Kafka, a book was an axe for the frozen sea within; for the older cohort of Gen X writers, it was more like a hacksaw to cut through the barred cell of cynicism.

This was the environment—quiescent in politics, self-consciously sincere in literature—in which Smith and her contemporaries came of age. Just as they started to publish their first books, however, the stopped clock of history resumed with a vengeance. It is unnecessary to list the series of political and geopolitical shocks that have occurred since 2000. For the millennial generation, adulthood has been defined by apocalyptic fears, political frenzy, and glimpses of utopia, whether in Chicago’s Grant Park on election night 2008 or in New York’s Zuccotti Park during Occupy Wall Street in 2011.

The children of the Seventies tend to feel out of place in this new world. It’s not that they naïvely looked forward to a future of peace and harmony and are offended to find that it has not materialized. It is rather that their literary gaze was fixed within at an early age, and they continue to believe that the most authentic way to write about history is as the deteriorating climate through which the self moves.

The self, meanwhile, they approach with mistrust—a reaction against the heart-on-sleeve sincerity of their elders. Many of them have turned to autofiction, a genre which is often criticized as narcissistic—a way of shrinking the world to fit into the four walls of the writer’s room. In fact, it has served these writers as an antidote to the grandiosity of memoir, which tends to falsify in the direction of self-flattery—as this generation learned from the spectacular implosion of James Frey’s 2003 bestseller, A Million Little Pieces. By admitting from the outset that it is not telling the truth about the author’s life, autofiction makes it possible to emphasize the moral ambiguities that memoir has to apologize for or hide. That makes it useful for writers who are not in search of goodness, neither within themselves nor in political movements.

For Sheila Heti, this resistance to goodness takes the form of artistic introspection, which busier people tend to judge as selfish and idle. In How Should a Person Be?, from 2010, a character named Sheila has dinner with a young theater director named Ben, who has just returned with a friend from South Africa. “It was just such a crushing awakening of the colossal injustice of the way our world works economically,” he says of their trip, that he now wonders whether his work as a theater director—“a very narcissistic activity”—is morally justifiable. Yet nothing could be more narcissistic, in Heti’s telling, than such moral preening, and Sheila instinctively resists it. “They are so serious. They lectured me about my lack of morality,” she complains. She loathes the idea of having “to wear on the outside one’s curiosity, one’s pity, one’s guilt,” when art is concerned with what happens inside, which can only be observed with effort and in private. “It’s time to stop asking questions of other people,” she tells herself. “It is time to just go into a cocoon and spin your soul.”

Teju Cole’s 2011 novel Open City offers a more ambivalent version of the same idea. Julius, the narrator, can’t justify his aesthetic self-absorption on the grounds that he is an artist, as Sheila does, since he is a psychiatrist. It’s an ironic choice of profession for a man we come to know as guarded and aloof. Cole builds a portrait of Julius through his daily interactions with other people, like the taxi driver whose cab he enters gruffly. “The way you came into my car without saying hello, that was bad,” the driver rebukes him. “Hey, I’m African just like you, why you do this?” Julius apologizes for this small breach of solidarity, but insincerely: “I wasn’t sorry at all. I was in no mood for people who tried to lay claims on me.”

Indeed, for most of the novel he is alone, meditating in Sebaldian fashion on the atrocities of history as he takes long walks through Manhattan. When, during a trip to Brussels, he meets a man who wants to intervene in history—Farouq, a young Moroccan intellectual who declares that “America is a version of Al-Qaeda”—Julius is decidedly unimpressed:

There was something powerful about him, a seething intelligence, something that wanted to believe itself indomitable. But he was one of the thwarted ones. His script would stay in proportion.

Open City can’t be said to endorse Julius’s aesthetic solipsism. On the contrary, the last chapter finds him trapped on a fire escape outside Carnegie Hall in the rain, a striking symbol of a man isolated by culture. Just moments before, he had been united with the rest of the audience in Mahlerian rapture; now, he reflects, “my fellow concertgoers went about their lives oblivious to my plight,” as he tries to avoid slipping and falling to his death. The scene is Cole’s acknowledgment that aesthetic consciousness remains passive and solipsistic even when experienced in common, and that danger demands a different kind of solidarity—one that is active, ethical, even political. Yet Cole conjures Julius’s aristocratic fatalism in such intimate detail that the “Rejoice! Believe!” approach—to literature, and to life—can only appear childish.

Writers of this cohort do sometimes try to imagine a better world, but they tend to do so in terms that are metaphysical rather than political, moving at one bound from the fallen present to some kind of messianic future. In her 2022 novel Pure Colour, Heti tells the story of a woman named Mira whose grief over her father’s death prompts her to speculate about what Judaism calls the world to come. In Heti’s vision, this is not a place to which the soul repairs after death, nor is it some kind of revolutionary political arrangement; rather, it is an entirely new world that God will one day create to replace the one we live in, which she calls “the first draft of existence.”

The hardest thing to accept, for Heti’s protagonist, is that the end of our world will mean the disappearance of art. “Art would never leave us like a father dying,” Mira says. “In a way, it would always remain.” But over the course of Pure Colour, she comes to accept that even art is transitory. In a profoundly self-accusing passage, she concludes that a better world might even require the disappearance of art, since

art is preserved on hearts of ice. It is only those with icebox hearts and icebox hands who have the coldness of soul equal to the task of keeping art fresh for the centuries, preserved in the freezer of their hearts and minds.

Tao Lin’s unnerving, affectless autofiction leaves a rather different impression than Heti’s, and he has sometimes been identified as a voice from the next generation, the millennials. But his 2021 novel Leave Society shows him thinking along similar lines as the children of the Seventies. In Taipei, from 2013, Lin’s alter ego is named Paul, and he spends most of the novel joylessly eating in restaurants and taking mood-altering drugs. In Leave Society he is named Li, but he is recognizably the same person, perched on a knife-edge between extreme sensitivity and neurotic withdrawal. In the interim, he has decided that the cure for his troubles, and the world’s, lies in purging the body of the toxins that infiltrate it from every direction.

Like Heti, Lin anticipates a great erasure. All of recorded history, he writes, has been merely a “brief, fallible transition . . . from matter into the imagination.” Sometime soon we will emerge into a universe that bears no resemblance to the one we know. Writers, Lin concludes, participate in this process not by working for social change but by reforming the self. “Li disliked trying to change others,” Lin writes, and believed that “people who are concerned about evil and injustice in the world should begin the campaign against those things at their nearest source—themselves.”

One way or another, writers in this cohort all acknowledge the same injunction—even the ones who struggle against it. In his new book of poems, The Lights, Ben Lerner strives to elaborate an idea of redemption that is both private and social:

I don’t know any songs, but won’t withdraw. I am dreaming

the pathetic dream of a pathos capable of redescription,

so that corporate personhood becomes more than legal fiction.

A dream in prose of poetry, a long dream of waking.

The dream of uniting the sophistication of art with the straightforwardness of justice also animates Lerner’s fiction, where it often takes the form of rueful comedy. In 10:04, the narrator cooks dinner for an Occupy Wall Street protester, but when asked how often he has been to Zuccotti Park, he dodges the question. His activism is limited to cooking, which he pompously describes as a way of being “a producer and not a consumer alone of those substances necessary for sustenance and growth within my immediate community.” That the dream never becomes more than a dream betrays Lerner’s similarity to Lin, Heti, and Cole, who frankly acknowledge the hiatus between art and justice, though without celebrating it.

Zadie Smith has always been too deeply rooted in the social comedy of the English novel to embrace autofiction, yet she also registers this disconnect, as can be seen in the way her influences have shifted over time. When it was first published, White Teeth was compared to Infinite Jest and Don DeLillo’s Underworld as a work of what James Wood called “hysterical realism.” The book’s arch humor, proliferating plot, and penchant for exaggeration owe much to the author Wood identified as the “parent” of that genre: Charles Dickens.

When Smith says that a woman “needed no bra—she was independent, even of gravity,” she is borrowing Dickens’s technique of making characters so intensely themselves that their essence saturates everything around them—as when he writes of the nouveau riche Veneerings, in Our Mutual Friend, that “their carriage was new, their harness was new, their horses were new, their pictures were new, they themselves were new.” Dickens is a guest star in The Fraud, appearing at several of William Ainsworth’s dinner parties, and the news of his death prompts Eliza Touchet to offer an apt tribute: “She knew she lived in an age of things . . . and Charles had been the poet of things.”

But Dickens, who at another point in the novel is gently disparaged for his moralizing “sermons,” is no longer the presiding genius of Smith’s fiction. (Smith wrote in a recent essay that her first principle in taking up the historical novel was “no Dickens,” and she expressed a wry disappointment that he had forced his way into the proceedings.) Her 2005 novel, On Beauty, was a reimagining of E. M. Forster’s Howards End, and while her style has continued to evolve from book to book, Forster’s influence has been clear ever since, in everything from her preference for short chapters to her belief in “keep[ing] one’s mind open.”

Smith’s affinity for Forster owes something to their analogous historical situations. An Edwardian liberal who lived into the age of fascism and communism, Forster defended his values—“tolerance, good temper and sympathy,” as he put it in the 1939 essay “What I Believe”—with something of a guilty conscience, recognizing that the militant younger generation regarded them as “bourgeois luxuries.”

At the end of The Fraud, Eliza encounters Mr. Bogle’s son Henry, who has grown disgusted with his father’s quietism and become a political radical. He reproaches her for being more interested in understanding injustice than in doing something about it, proclaiming:

By God, don’t you see that what young men hunger for today is not “improvement” or “charity” or any of the watchwords of your Ladies’ Societies. They hunger for truth! For truth itself! For justice!

This certainty and urgency is the opposite of keeping one’s mind open, and while Mrs. Touchet—and Smith—aren’t prepared to say that it is wrong, they are certain that it’s not for them: “This essential and daily battle of life he had described was one she could no more envisage living herself than she could imagine crossing the Atlantic Ocean in a hot air balloon.”

Whether they style themselves as humanists or aesthetes, realists or visionaries, the most powerful writers who were born in the Seventies share this basic aloofness. To the next generation, the millennials, their disengagement from the collective struggle may seem reprehensible. For me, as I suspect is the case for many readers my age, it is part of what makes them such reliable guides to understanding, if not the times we live in, then at least the disjunction between the times and the self that must try to negotiate them.

0 notes

Photo

#highlander#tv shows#davis-panzer productions#adrian paul#alexandra yandernoot#stan kirsch#amanda wyss#jim byrnes#philip akin#michel modo#lisa howard#elizabeth gracen#peter wingfield#illustration#vintage art#alternative movie posters

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

undefined

youtube

Who wants to live forever by: freddy mercury and Queen from the Highlander movies and TV show.

#i am duncan macleod of the clan macleod. born four hundred years ago in the highlands of scotland. i am immortal and i am not alone.#adrian paul#methos#peter wingfield#richie#stan kirsch#alexandra vandernoot#tessa#elizabeth gracen#amanda darieux#joe dawson#jim byrnes

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

A family with 5 children just lost their mother: if you can, please donate, if not, please pray!

50 notes

·

View notes

Photo

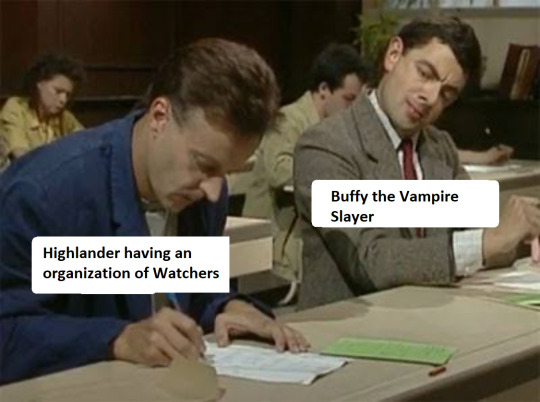

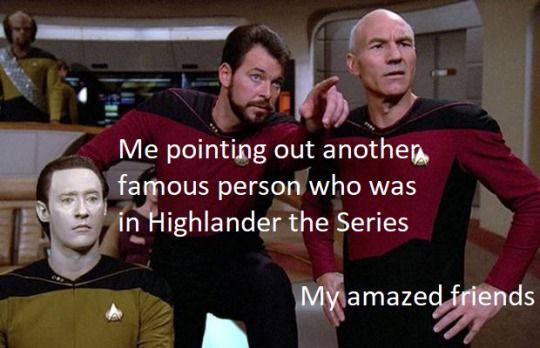

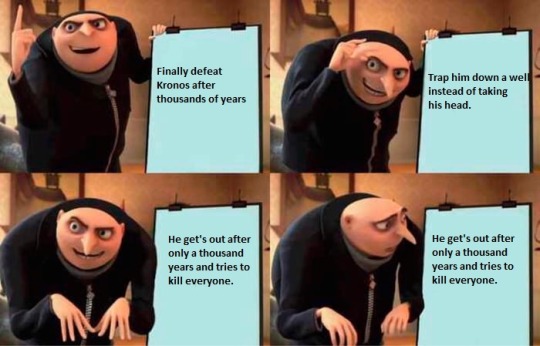

More Highlander memes!

#2023 and still making these#highlander#highlander the s#highlander the series#highlander franchise#duncan macleod#connor macleod#methos joe dawson#methos#joe dawson#amanda darieux#richie ryan#adrian paul#peter wingfield#elizabeth gracen#stan kirsch#valentine pelka#christopher lambert#clancy brown#sean connery#memes#patrick stewart#buffy#new year new memes#highlander memes#90s#nostolgia#tv#tv show#tv series

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

You ever love a dead character so much and trust the writers so little that you just want them to never be mentioned again?

#kirsch family#richie kirsch#wayne bailey#ethan landry#quinn bailey#amber freeman#elizabeth ray#peter ray#jason carver#txt

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

—Lee Siegel, “Misreading Auden”

When last we saw Lee Siegel here at Grand Hotel Abyss, he’d misremembered Roth’s Ghost Writer as a novel in which the hero masturbates over a picture of Anne Frank. In his latest scandal, he writes a polemic against a New York Times essay on Auden’s “Musée des Beaux Arts” he misattributed, in the first version of his piece, to Elizabeth Gilbert, author of Eat, Pray, Love. (The real author is a poet qua Twitter personality—though, to be fair, I am a novelist qua blogger.) Anyway, I agree in general with the gravamen of Siegel’s complaint as screenshotted above.

Auden’s poem is annoying, however: “the dogs go on with their doggy life”—God save us from the incorrigible cutesiness of English writers. Moreover, in the second stanza, how can it be that “everything turns away / Quite leisurely from the disaster” when in fact the ploughman and the ship captain turn away or never even look in the first place because they’re working? And finally, isn’t the poem’s (moralistic) purpose to contrast the life of Jesus evoked in the first stanza (“miraculous birth,” “dreadful martyrdom”) as an event in human history that was “an important failure” permitting us to recognize failure as important, with the whole hubris, brutality, and cynicism of the pagan world typified both by Icarus’s vaulting ambition and his unlamented fall? Isn’t the humble Christian-postmodern poet in fact chastising the Old Masters for their heathen coldness by “regarding the pain of others” they’d relegated to the margin of their splendid panorama?

The poem, therefore, is an origin myth for the very moralism Siegel decries, revealing the Christian root of middle-class progressive self-congratulation for deigning to notice terror, unlike cruel aesthetes and the deplorable working class. Adam Kirsch, contrasting postmodern Auden with modern Pound and Yeats, renders the case more sympathetically in “To Hold in a Single Thought Reality and Justice”:

In the 1930s, he thought justice meant transforming reality in the name of a political ideal. In the 1940s and after, he began to think that this kind of utopianism was actually a sure path to injustice—as it had proved to be in the Soviet Union. Instead, he started to think that the true definition of justice was doing justice to reality, by registering the world as it is, in all its variousness and complexity and individuality. This was a new, essentially postmodernist and antimodernist, view of the relationship between art and the world.

On the other hand, John Dolan, a writer as controversial as Seigel (and for some of the same reasons), pronounced Auden “the worst famous poet of the 20th century” a decade ago:

Auden’s poems after 1940 enact a slow, elderly courtship of the Deity via European high culture as interpreted by a man of limited intellect. As with that other bard of the bell curve, William Carlos Williams, you get a lot of poems based on the paintings of Breughel. Odd, you might think, that two major Modernist poets should make so much of such a busy, cheery Norman Rockwell of a painter. But that’s the point: Breughel is a happy moron, like his 20th century champions. For Williams, he’s the artistic equivalent of a baseball game; for Auden, playing that old-world sage role for all it’s worth in Manhattan, Breughel, incredibly, becomes one of the “old masters” in that famous, rotten hyperbaton, “About suffering they were never wrong, the old masters….” This poem, “Musee des Beaux Arts,” sums up Auden’s meaning and value rather nicely: it’s fake high-European culture for a busy American audience that knows nothing about anything, and simply wants an imported sage to embody the mournful quietism which is the only stance it needs from such decorative figures.

I don’t go that far. I like Auden when he’s singsong and openly polemical, a kind of merry counter-Yeats; and he coined a few imperishable phrases, rendering the poet’s most crucial service to the language. I also sympathize with Auden’s later politics, if only by default, more than Dolan does, even if I think they’re harder to hold with any aesthetic dignity than the politics-with-a-capital-P of “Spain”—or “Easter, 1916.” I think it was Hayden Carruth who said a poet can’t be a liberal or conservative, but only a radical or reactionary. Auden’s conservative liberalism or liberal conservatism would fit better in a novel. But “Musée” shrouds its moralism in excess and imprecise verbiage so that the Christian sermon takes us unawares, a gesture I no doubt unreasonably resent.

#w.h. auden#lee siegel#adam kirsch#john dolan#poetry#literature#english literature#literary criticism

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Celebrity Deaths 2020

JANUARY

Lexii Alijai - Jan. 1 (Rapper)

Nick Gordon - Jan. 1 (Reality Star)

Carlos De Leon - Jan. 1 (Boxer)

Don Larsen - Jan. 1 (Baseball Player)

Sam Wyche - Jan. 2 (Football Coach)

John Baldessari - Jan. 2 (Conceptual Artist)

Derek Acorah - Jan. 3 (TV Show Host)

Gene Reynolds - Jan. 3 (Director)

Andrea Arruti - Jan. 3 (Voice Actress)

Walter Learning - Jan. 5 (Director)

Ria Irawan - Jan. 6 (Movie Actress)

Neil Peart - Jan. 7 (Drummer)

Silvio Horta - Jan. 7 (Screenwriter)

Elizabeth Wurtzel - Jan. 7 (Novelist)

Harry Hains - Jan. 7 (TV Actor)

*Edd Byrnes - Jan. 8 (TV Actor)

Buck Henry - Jan. 8 (Screenwriter)

Maxie - Jan. 8 (YouTube Star)

Alexis Eddy - Jan. 9 (Reality Star)

Brian James - Jan. 10 (Rugby Player)

Stan Kirsch - Jan. 11 (TV Actor)

La Parka - Jan. 12 (Wrestler)

Rocky Johnson - Jan. 15 (Wrestler) *Dwayne Johnson's Dad*

Christopher Tolkien - Jan. 16 (Novelist)

David Olney - Jan. 18 (Folk Singer)

Bubby Jones - Jan. 18 (Race Car Driver)

Joe Shishido - Jan. 18 (Movie Actor)

Jimmy Heath - Jan. 19 (Saxophonist)

Terry Jones - Jan. 21 (Comedian)

Jim Lehrer - Jan. 2(Journalist)

Gudrun Pausewang - Jan. 23 (Young Adult Author)

Jim Lehrer - Jan. 23 (Journalist)

Clayton Christensen - Jan. 23 (Non-Fiction Author)

Sean Reinert - Jan. 24 (Drummer)

Rob Rensenbrink - Jan. 24 (Soccer Player)

**Kobe Bryant - Jan. 26 (Basketball Player)

*Gianna Bryant - Jan. 26 (Family Member) *Kobe's Daughter*

Bob Shane - Jan. 26 (Rock Singer)

John Altobelli - Jan. 26 (Baseball Manager)

Keri Altobelli - Jan. 26 (Family Member)

Jack Burns - Jan. 27 (Comedian)

Harriet Frank Jr. - Jan. 28 (Screenwriter)

Nicholas Parsons - Jan. 28 (TV Show Host)

Tofig Gasimov - Jan. 29 (Politician)

John Andretti - Jan. 30 (Race Car Driver)

Fred Silverman - Jan. 30 (TV Producer)

Mary Higgins Clark - Jan. 31 (Novelist)

Anne Cox Chambers - Jan. 31 (Entrepreneur)

FEBRUARY

Gene Reynolds - Feb. 3 (Director)

Nadia Lutfi - Feb. 4 (Movie Actress)

Kamau Brathwaite - Feb. 4 (Poet)

Kirk Douglas - Feb. 5 (Movie Actor)

Beverly Pepper - Feb. 5 (Sculptor)

*Raphael Coleman - Feb. 6 (Movie Actor)

Jhon Jairo Velásquez - Feb. 6 (Criminal)

Orson Bean - Feb. 7 (Movie Actor)

Paula Kelly - Feb. 8 (Stage Actress)

Robert Conrad - Feb. 8 (TV Actor)

Qing Han - Feb. 8 (Illustrator)

Keelin Shanley - Feb. 8 (Journalist)

Mirella Freni - Feb. 9 (Opera Singer)

Abam Bocey - Feb. 10 (Comedian)

Lyle Mays - Feb. 10 (Planist)

Louis-Edmond Hamelin - Feb. 11 (Non-Fiction Author)

Jamie Gilson - Feb. 11 (Children's Author)

Hamish Milne - Feb. 12 (Pianist)

Jimmy Thunder - Feb. 13 (Boxer)

Lynn Cohen - Feb. 14 (Movie Actress)

Esther Scott - Feb. 14 (Voice Actress)

John Shrapnel - Feb. 14 (Movie Actor)

Caroline Flack - Feb. 15 (TV Show Host)

Amie Harwick - Feb. 15 (Doctor)

Vatroslav Mimica - Feb. 15 (Director)

Jason Davis - Feb. 16 (Voice Actor)

Zoe Caldwell - Feb. 16 (Stage Actress)

Tony Fernandez - Feb. 16 (Baseball Player)

Frances Cuka - Feb. 16 (TV Actress)

Harry Gregg - Feb. 16 (Soccer Player)

Ja'net Dubois - Feb. 17 (TV Actress)

Owen Bieber - Feb. 17 (Activist)

Charles Portis - Feb. 17 (Novelist)

Lindsey Lagestee - Feb. 18 (Country Singer)

Ashraf Sinclair - Feb. 18 (Movie Actor)

Pop Smoke - Feb. 19 (Rapper)

Jose Mojica Marins - Feb. 19 (Director)

Gust Graas - Feb. 19 (Painter)

Lisel Mueller - Feb. 21 (Poet)

Tao Porchon-Lynch - Feb. 21 (Fitness Instructor)