#irish famine

Text

The only appropriate way to spend St. Patrick’s Day is to continue to stand up against the occupation and oppression of all people around the world. 🇵🇸🇮🇪

#free palestine#from the river to the sea palestine will be free#ireland#irish famine#Irish genocide#palestine#palestinian genocide#free gaza#gaza#gaza genocide#anti colonialism#anti colonization#genocide#st patricks day#leftist#leftblr#communist#socialist#communism#socialism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#leftist politics#human rights#oppression#end occupation#israel is a terrorist state#israeli apartheid

699 notes

·

View notes

Text

The high I'm feeling blocking anyone complaining about celebrating the queen's death. Absolutely ecstatic.

#the queen#queen#queen of england#SHES DEAD#queens dead#queen elisabeth ii#queen elizabeth#queen elisabeth#i dont wven k ow how she spells her name!!#ireland#irish#irish famine#irish history#these fuckers are the same ones whod defend margaret thatcher

288 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just watched a leftist argue with a British monarchist and, unsurprisingly, the monarchist had some banger takes like "Genocide is good" and "The Famine was the Irish peoples fault because they were overpopulated." Really makes you think that the British Crown was a fucking parasite that stole from the Irish people and oh wait. They are parasites and always have been.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

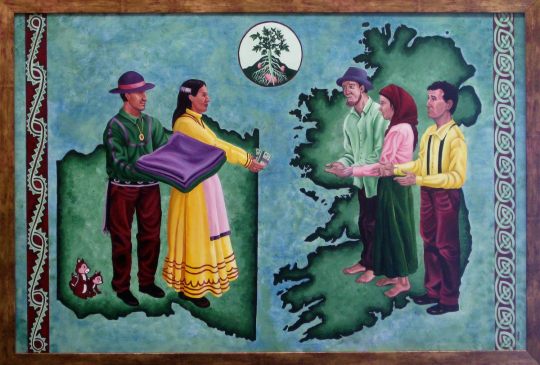

THE YEAR 1847 WAS AN extremely difficult one for the Irish people. Known as “Black 47,” this was the worst year of the famine in Ireland, where close to one million people were starving to death. Humanitarian aid came from around the world, but the unexpected generosity of the Choctaw Nation stands out, and began a bond between the two people that continues to this day.

The Choctaw Native Americans raised $170 of their own money—equivalent to thousands of dollars today— in aid to supply food for the starving Irish. This exemplifies the incredible generosity of the Choctaw people, because just 16 years before, they were forced by U.S. President Andrew Jackson to leave their ancestral lands and march 500 miles on the “Trail of Tears,” in terrible winter conditions. Many did not survive.

Today, the Irish people are still grateful for the generosity of the Choctaw people. A monument stands in Midleton’s Bailick Park as a tribute to the tribe’s charity during the Great Famine. Named “Kindred Spirits,” the magnificent memorial features nine giant stainless steel feathers, shaped into an empty bowl.

The creator, artist Alex Pentak, explained, “I wanted to show the courage, fragility and humanity that they displayed in my work.”

Beyond the monument, there are many other examples of the continued link between the Irish and Choctaw people. In 1990, several Choctaw leaders took part in the first annual Famine walk at Doolough in County Mayo; two years later, Irish commemoration leaders walked the 500 mile length of the Trail of Tears. A former Irish president is now an honorary Choctaw Chief. Most importantly, both Choctaw and Irish people now work together to provide assistance for people suffering from famine worldwide.

#Alex Pentak#Irish#Choctaw#Trail of Tears#1847#Black 47#famine#ireland famine#cw death#choctaw nation#native americans#andrew jackson#Midleton’s Bailick Park#Bailick Park#Kindred Spirits#famine walk#Doolough#irish famine#solidarity#atlas obscura#atlasobscura#Cork Ireland#Ireland#jackson hotaling#article

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

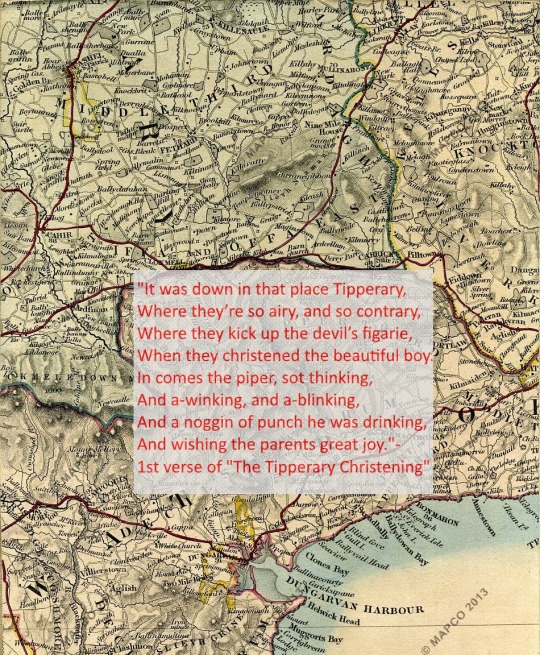

The Millses in County Tipperary, Ireland

Map is courtesy of "Map of Ireland, Compiled from the Surveys of the Board of Ordnance and other approved Documents By J. & C. Walker 1838" and first verse of "The Tipperary Christening" is courtesy of an Irish genealogy site. Ballysheehan, near Cashel, is pictured in the map above, the location where John Mills said he was born.

As noted in my family history, Mills family members were living in County Tipperary, Ireland, including John Rand Mills and others. The Mills family has established roots in Tipperary. [1]

In 1766, a census recorded a Protestant man named Jno (either John or Jonathan) Mills living on Cashel Rock and a papist woman named Margaret Mills, living in Mealiffe. This census was, as irelandgenweb describes it,

the largest religious census...when each Church of Ireland minister was requested to provide a listing of the members of each denomination in his parish. Although some were completed as requested, many ministers provided only the details on Church of Ireland parishioners, and omitted Catholics, Presbyterians, etc. Others provided a complete survey of all local inhabitants, including family names and the numbers of children in the household....Parishes in this instant are Church of Ireland parishes which are much like the civil parish borders in later years.

Sadly, no one named Mills is listed in the 1821 census fragments. However, they are listed elsewhere. They were listed in applotment books for tithes, which were a "unique land survey taken as a way to determine the amount of tax payable by landholders to the Church of Ireland," with the books representing "a virtual census for pre-Famine Ireland. In the original enumeration, each landholder was recorded along with details such as townland, size of holding, land quality and types of crops," ranging from 1815 to 1838.

This post was originally published on WordPress in May 2018.

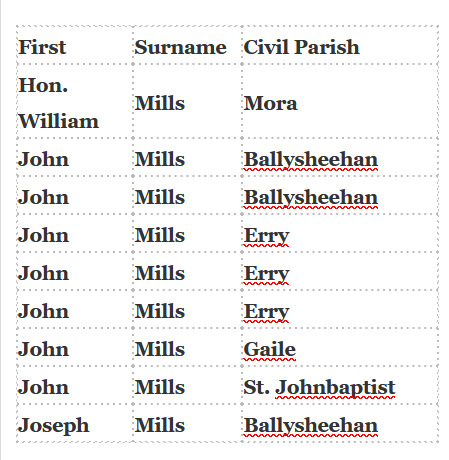

Specifically, in the tithe books, for Middlethird Barony, there were nine Millses mentioned, which I have re-ordered by first name, then surname, rather than surname being first.

As I have noted earlier on this blog, the John Mills who landed in Warren County was undoubtedly one of the two John Millses who were living in Ballysheehan. Digging into the data further, on can narrow it down by parish. This shows that there are three Millses living in the Ballysheehan parish: John (in Peake), John (in Ballinree), and Joseph (in Ballysheehan). Sadly, the deposition John Mills gives in Warren County does not give these specifics, only giving the parish, but it is clear, he is either the man who was living in Peake or the man in Ballinree. Furthermore, of the other six Millses listed above:

one was living in Castleblake (Honorable William Mills)

one was living in an unnamed town in St. Johnbaptist Parish (another John Mills)

one is living in Killough (yet another John Mills)

two were living in Grangebeg (two other John Millses)

one was living in Grangemore (one final John Mills)

For this, I created the following map, to show were all these Millses were living at the time, showing how they are spread out across County Tipperary which I put together on Google Earth: [2]

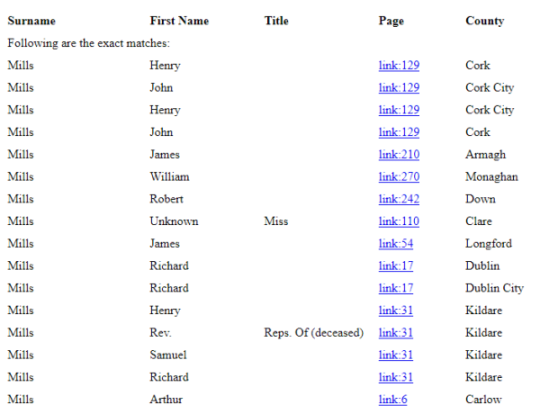

In 1831, one John Mills was on a list of "those liable for tithes who had not paid" and he was living in Grangemore as a farmer. Listings in other surviving records do not list anyone else with the surname of Mills. The same goes for House, Quarto, Tenure, Field & Miscellaneous Books for varied Irish parishes, assembled by Richard Griffith, concentrated in the later 1840s to early 1850s. This could imply that many of the Mills family members had either died or immigrated to the United States by that time. Griffith's Valuation from 1848 to 1864 lists a "Patrick Mills" in Erry Parish in the early 1850s, three Millses (Mary, Anne and William) in St. Johnbaptist Parish around the same time, and a John Mills in Killough as well.

Is it is of any surprise that by 1876 there 16 individuals with the surname of Mills listed as land owners in Ireland? The answer is a strong no.

This post gives more context on the Mills family in Ireland and a place to start for further research!

© 2018-2022 Burkely Hermann. All rights reserved.

Notes

[1] Some records show a "John Mills" buried in the nearby county of Wicklow but that is not what I'm referring to.

[2] Except for the one in St Johnbaptist Parish, because the only St. Johnbaptist that comes up are churches in Cashel and I'm not sure if he was living in Cashel.

#tipperary#ireland#county tipperary#irish history#irish genealogy#irish famine#19th century#genealogy#family history#ancestry#wordpress#google earth#census#family mystery#mysteries#rock of cashel

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

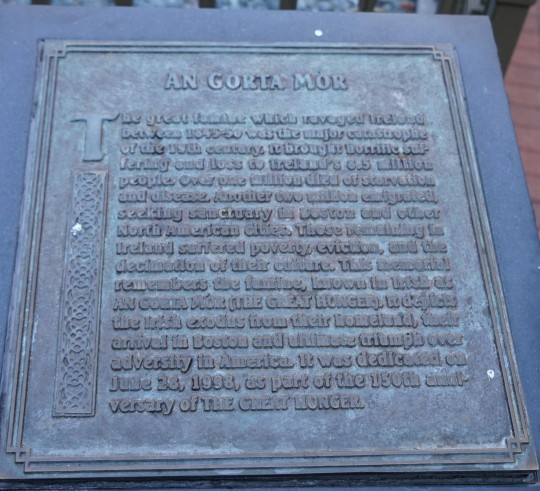

Irish famine memorial, Boston MA. October 20, 2022

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

So, my mother-in-law called me up out of the blue to tell me about a "very well done historical program" she was watching on PBS about the Great Hunger, and how she thought I'd really enjoy it if I can find it.

I would've been put off given the morbid topic, except...

A huge portion of my MA research centered around the Great Hunger. I don't think I've ever spoken about this with her. Apparently I just seem like One Of Those People?

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

History News Network oped: Irish Legend Should Inspire the Fight Against Famine Today

The hit Irish show Riverdance includes a segment titled The Countess Cathleen, which was originally a verse drama by William Butler Yeats, published in 1893.

This legendary tale of Countess Cathleen (aka Kathleen) begins with Irish peasants starving to death during a famine. Demons have descended upon the desperate poor trying to get them to sell their souls to the Devil in exchange for gold to…

View On WordPress

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sean Bothar (Old Road)

Follow the path of Sean BotharA haunted place where once stood homesFeel the ghosts of An Gorta MórLingering among the tumbled stones

Too poor to answer the immigrant callToo weak to throw an American wakePut to work building useless wallsIn the mountains above Corrib’s Lake

This old road lined with hazel and gorseFamine cottages with the family namesBears the hoof prints of the pale rider’s…

View On WordPress

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The great cause of Jones' political life, bringing workers to Australia, was once more pressing on his mind. He could not understand why Britain wasted money on starving Irish.

How much better employed would have been the £8,000,000 that was spent in the Irish famine, had it been spent in sending your excess of numbers here and elsewhere – where, in time, they would acquire happy homes, and be surrounded with comfort; but the English government, by its absurd economy, will give no assistance to emigration – thus retaining the starving people at home, waiting for another visitation of the kind.

"Killing for Country: A Family History" - David Marr

#book quotes#killing for country#david marr#nonfiction#richard jones#politics#workers#australia#workforce#emigration#britain#money#potato famine#irish#starving#irish famine#economy

0 notes

Text

Genuine question, should what is know as the Irish Famine be called instead the Irish Starvation since the British could have provided aid but didn’t and also actively prevented aid from getting to them?

#Irish famine#Irish starvation#potato famine#irish potato famine#British genocide#genuine question#question#Ireland

1 note

·

View note

Text

he couldve ended the irish famine with all that potato

1 note

·

View note

Text

Gran Hambruna Irlandesa

«El Todopoderoso, de hecho, envió la plaga, pero los ingleses crearon la Hambruna.»

—John Mitchel, 1861.

—> Entre 1843 y 1844, llega a Inglaterra la noticia de que los campos de patata de Estados Unidos y Canadá han sido asolados por una misteriosa enfermedad.

Los barcos provenientes de Baltimore, Filadelfia y de la ciudad de Nueva York transportaban el cultivo a Europa, ignorantes de su condición, y para mediados de agosto de 1845, la enfermedad había alcanzado gran parte del norte y centro de Europa; Bélgica, los Países Bajos, el norte de Francia y el sur de Inglaterra.

—> 16 de agosto de 1845: The Gardeners' Chronicle and Horticultural Gazette informa de una plaga de carácter inusual en la isla Wight. El 23 de agosto comunica la noticia de una terrible enfermedad que se ha desatado entre la cosecha de patatas. En Bélgica, se dice que los campos están «completamente desolados».

—> 11 de septiembre de 1845: El Freeman's Journal notifica la aparición «de lo que se llama cólera en las patatas de Irlanda, especialmente en el norte». El 13 de septiembre, The Gardeners' Chronicle anuncia oficialmente la aparición de la plaga de la patata en Irlanda.

Muchas de las patatas se habían vuelto negras y se habían podrido, con las hojas marchitas. Más de la mitad de los irlandeses, sobre todo los de las zonas del noroeste —las más concentradas—, dependían exclusivamente de la patata (la avena y el ganado habían dejado de ser accesibles por sus precios).

Los fallos de la cosecha irlandesa eran relativamente comunes —aunque solo la situación de 1741 era siquiera comparable—, por lo que el Gobierno británico, en ese momento dirigido por el tory Robert Peel, tardó en darse cuenta de la gravedad.

De hecho, una semana después, una consulta del Gobierno concluyó que, aunque había habido fallos, la recogida era inusualmente abundante y podría compensar la pérdida.

Un mes después, otra consulta revelaría que la pérdida era mucho más grave en 17 de los 32 condados irlandeses. Entre un tercio y la mitad del cultivo había sido destruido.

El Gobierno encargó buscar una cura para la plaga, pero fracasó.

[No sería hasta 1882 que se descubriría que, si se esparcía una solución de sulfato cúprico sobre el protista Phytophthora infestans antes de infectar la raíz, se podía evitar la enfermedad.]

Agotadas las opciones por esa vía, se dieron cuenta de que tenían dos posibles soluciones: 1. Detener las exportaciones del grano que cultivaban los terratenientes de Leinster y era vendido a Gran Bretaña (en 1844 habían sido exportadas 294.000 toneladas de grano, y en 1845, 485.000) o 2. Importar más alimentos, a pesar de los múltiples problemas, como el miedo de los países a la plaga de la patata, que había causado que prohibiesen la exportación de comida, o la Corn Law, que debía proteger a los granjeros locales mediante la prohibición de las importaciones foráneas de grano.

La primera medida fue exigida por múltiples personalidades —entre ellos, Daniel O'Connell—, en una reunión con el Lord Teniente de Irlanda. Sin embargo, el Gobierno lo descartó al concluir que con eso no sería suficiente para alimentar a toda la población irlandesa.

Aun así, para la Historia ha quedado como una de las grandes traiciones de Gran Bretaña hacia Irlanda, aunque todavía estamos empezando.

Se terminó por derogar la Corn Law, con tal de impulsar la importación de alimento desde América para hacer frente al problema. En Westminster, los opositores de Peel le acusaron de estar utilizando la plaga para derogar la ley, o incluso de exagerar los efectos de la enfermedad de la patata en Irlanda.

—> Noviembre de 1845: £105.000 en maíz son importados desde Estados Unidos, y £46.000 desde Gran Bretaña. Debido a una ley de 1838, denominada Irish Poor Law, estas ayudas solo pueden ser distribuidas desde los asilos de pobres repartidos por el territorio irlandés y organizados por consejos locales denominados Law Unions.

Sin embargo, Peel era consciente de que no tenían la capacidad suficiente para hacerlo efectivo, así que estableció una comisión temporal de ayuda. Esta organizaría la distribución del alimento y su precio, aunque aquello no evitó que hubiese gente que tuviese que dar sus ropas y muebles para conseguir comida.

En un principio, muchos irlandeses no quisieron aceptar su caridad, pero terminaron por no tener otra opción. También se organizaron trabajos locales que, en su pico, tuvieron contratados alrededor de 140.000 personas. Pese a que los salarios eran muy bajos, lograron mantener a la mitad de ellas.

Las medidas del denominado como programa de ayuda de Peel lograron alimentar a más de un millón de personas durante un mes, aunque apenas había inanición en 1845. Paradójicamente, serían estas las que causarían el desmantelamiento del Gobierno tory en julio de 1846, al mismo tiempo que la comisión de ayuda enviaba malas noticias desde Irlanda.

—> Primavera de 1846: Se planta una cantidad mayor de patatas con tal de asegurarse de que la plaga no se repita. Sin embargo, ya en julio, la comisión envía un mensaje a Londres en el que lamenta que la previsión de la cosecha de ese año sea incluso más descorazonadora que la del anterior; la plaga ha aparecido antes y sus destrozos son mucho mayores.

El nuevo primer ministro whig —una especie de «liberal»—, John Russell, había acusado a Peel el año anterior de exagerar la situación por las pocas muertes. Su razonamiento era que habría cosecha suficiente que no hubiese sufrido los efectos de la plaga como para alimentar a la población y que no hubiese problemas, así que encargó a la Comisión que controlase la situación y repasase los efectos de las medidas de 1845 antes de implementar las suyas.

—> Mediados de agosto de 1846: Russell pone en marcha su plan en el Parlamento: la importación de alimento puede ser dejada a los mercaderes locales (la mayoría había dicho que no lo haría a no ser que se les ofreciesen las garantías necesarias; solo en Cork, Donegal y Kerry una pequeña comisión de mercaderes locales se aseguró de proporcionar el maíz con permiso de Londres) mientras que el Gobierno se ocupará de ofrecer empleo para proporcionarles un sueldo para que puedan comprar su propio alimento.

Se continuarían los planes de trabajo de Peel, aunque el sueldo tendría que estar restringido a la media local. Seguía siendo bajo; entre 8 y 10 libras al día, que no llegaban para sostener a una familia, y, por si fuese poco, el pago solía retrasarse.

Para marzo de 1847, habría apuntadas aproximadamente 750.000 personas.

—> Otoño de 1846: La cosecha vuelve a fracasar en la isla, aunque en una mayor proporción que el año anterior.

—> Diciembre de 1846: La falta de comida y dinero se traduce en que, en las zonas dependientes de la patata, la gente se muere de inanición. Un informe de Cork de la época describe cómo la Hambruna se ha vuelto tan terrible que muchos son enterrados sin siquiera «juicio o ataúd», y cómo un doctor en particular investiga tres cuerpos; dos correspondientes a niños muy jóvenes que habían llegado «a pasitos» al poblado, muertos de hambre, dando a conocer la noticia de que su madre había fallecido y de que su padre «no les ha hablado en cuatro días y está frío», y el otro a una madre cuyo hijo había fallecido también hacía tiempo, todos roídos por las ratas.

Aun así, el Gobierno se negó a permitir que la comisión de ayuda extendiese el reparto de comida fuera del Munster occidental y Donegal, creyendo que sus medidas funcionarían.

El Illustrated London News comenzó a publicar grabados a modo de imágenes de las víctimas a partir de 1847.

Mucha gente viajaba a las ciudades para obtener ayuda. Al principio, los ciudadanos eran generosos, aunque, según fueron pasando los meses, la hospitalidad fue sustituida por el miedo. La mayoría de los mendigos eran atraídos y confinados por la noche en los mercados, para ser subidos a carros a la mañana siguiente y dejados a gran distancia de las ciudades. Una gran parte perecía al no tener adonde ir.

Los niveles de crimen, de forma inevitable, se duplicaron entre 1846 y 1847.

—> Invierno entre 1846 y 1847: Solo la caridad logra mantener viva a miles de personas.

Los sacerdotes católico repartían alimentos entre los locales; la Sociedad de Amigos recolectaba dinero en América y Gran Bretaña, y un grupo de empresarios londinenses reunían dinero, incluyendo £2.000 de la Reina Victoria (y aquí está la anécdota del sultán otomano que pretendía donar una cantidad mayor, £10.000, pero no se le permitió porque «no se podía donar más que la Reina de Inglaterra», aunque, si entro en todo lo que se decía desde el lado británico, no acabo nunca).

Los terratenientes, por otro lado, estaban en extremos opuestos: algunos rechazaban las ayudas, aprovechando la oportunidad para desalojar a pequeños arrendatarios de sus terrenos; otros ni siquiera vivían en Irlanda, y algunos se llegaron a arruinar intentando mantener a sus arrendatarios.

Durante este tiempo, varios miles de personas murieron, ya fuese de enfermedad o de inición.

En esos meses, las migraciones a América en masa comenzaron (antes de la Hambruna también las había; 50.000 personas por año, pero sobre todo del Úlster y Leinster: personas que se podían permitir pagar el pasaje), hasta hasta el punto de que, entre los dos años, hubo aproximadamente 350.000 irlandeses que abandonaron la isla.

Solo el 3% tuvieron sus billetes pagados por el Gobierno o sus terratenientes.

—> Primavera de 1847: El Gobierno acepta que su política ha fallado de una forma catastrófica. Para este momento, la Junta se ha gastado £5.000.000 en ayudas, sin esperar que los impuestos puedan compensarlo. Es desmantelada en marzo para restituir una versión similar al esquema original de Peel.

Sin embargo, en un principio, el Gobierno seguía sin querer proporcionar la comida cocinada; debía de darse cruda para que los irlandeses la preparasen. La comisión insistió, entre ellos, su líder, sir Randolph Routh, que destacaba sus esfuerzos por conseguir que los mercados aceptasen el plan de la sopa, argumentando que también economizaba su comida.

El Gobierno establecería entonces las cocinas de sopa para alimentar a los irlandeses. Las juntas de empleo público fueron desmanteladas, y las cocinas de sopa comenzaron proporcionar raciones a 780.000 personas en mayo, cifra que alcanzaría los 3 millones en agosto.

La comida no era de gran calidad nutricional, y tampoco había una gran cantidad de ella. Las raciones terminaban siendo menores a las recomendadas para cada edad, aunque era algo que decidían los comités locales.

En algunas zonas, la gente era rechazada por parecer saludable, y en otras ni siquiera obtenían una ración completa. Hubo personas que terminaron en los juzgados para luchar por su derecho a la comida.

En otras, los terratenientes y comisionados locales aumentaron la ración, e incluso la duplicaban para los más necesitados. Hay registros de que, en algunas, el número de raciones entregadas excedía a la población local.

Sin embargo, hay un consenso de que, incluso con las importaciones, el Gobierno no gastó ni de cerca lo suficiente en las cocinas de sopa. En estos años, uno de los distribuidores de Belmullet (donde, al contrario de lo que aparece en el fic, el asilo de pobres no se construiría hasta 1849. Sin embargo, debido a la que Irish Poor Law solo autorizaba a los asilos a repartir la ayuda, me parece algo extraño que no hubiese, aunque fuese, algo similar) protestaba por seguir viendo cadáveres famélicos, aunque insistía en estar haciendo todo lo que podían con sus recursos limitados.

Las distintas enfermedades comenzaron a ser un problema, y era común que los doctores y comisionados muriesen también por estas.

Los que emigraban las llevaban consigo, y, en promedio, el 40% de los que embarcaban en los «botes ataúd» moriría en la ruta o justo después de la llegada.

—> Junio de 1847: Las nuevas medidas de ayuda se publican como una extensión de la Irish Poor Law. Una cláusula de William Gregory exime de la ayuda a cualquiera que poseyese más de un cuarto de acre de tierra. Esta es bastante malinterpretada, y muchos de los que necesitan de la ayuda son rechazados —los agricultores pobres deben prácticamente ceder toda su tierra a los arrendadores para poder acceder a la ayuda—, y los terratenientes la utilizan para desalojar a miles de labradores indeseados de sus tierras.

—> Octubre de 1847: Ante el éxito de la cosecha, se supone que lo peor ya ha pasado; las cocinas de sopa se cierran —solo se dejan abiertas aquellas que se consideren estrictamente necesarias—, y se depende de solo los asilos de pobres como fuente de ayuda, a pesar de que la mayoría ya supera la capacidad de personas para la que están preparados y se han vuelto nidos de enfermedades.

La aproximación del Gobierno estaba lejos de la realidad. Si bien la cosecha de 1847 no había sido afectada por la plaga, la mayoría de la gente había sido contratada por la juntas de empleo y no había trabajado en sus campos, por lo que apenas se habían plantado y, por tanto recogido, patatas.

Y el invierno de 1847 a 1848 se cobraría más víctimas que el anterior, con la llegada definitiva de la fiebre y la disentería, que se declararían como epidemias. En Dublín, se daría por concluida en febrero de 1848, aunque en muchas zonas continuaría por uno o dos años más.

Mucha gente murió por estar debilitada por el hambre y la malnutrición.

—> Otoño de 1848: La plaga vuelve a la cosecha, destruyendo la mayor parte del cultivo. Con los asilos mejorados, las muertes no son tan numerosas como en el anterior.

—> Invierno de 1848 a 1849: La epidemia de cólera se ceba con toda Irlanda (especialmente ciudades como Drogheda, Galway, Belfast, Limerick, Waterford, Kilkenny y Cork) y Gran Bretaña, sin distinción de clase social. Sin embargo, siguen saliendo más perjudicados los irlandeses; el Gobierno aún no se ha retractado de considerar el final de la Hambruna un año antes.

Durante el siguiente, el Gobierno intentó convencer a los agricultores de acostumbrarse a nuevos cultivos, y, aunque tuvo éxito en algunas áreas, muchos no quisieron hacer el cambio. La Sociedad de Amigos compraría y harían funcionar una «granja modelo» para enseñarles nuevos métodos agrícolas.

El brote de cólera pareció cesar en mayo.

—> Otoño de 1849: Vuelve la plaga, aunque no con la misma intensidad que el año anterior. Sin embargo, el invierno volverá a ser complicado por el regreso del cólera, junto a la discusión sobre aislar a los enfermos.

Los asilos seguirían manejando la ayuda, lo que dificultó determinar cuál fue el fin de la Hambruna, que terminaría de forma gradual.

Se acuerda que fue entre 1849 y 1850, cuando los asilos tuvieron la capacidad de cuidar a los indigentes, aunque la emigración continuaría (en menor medida) entre 1848 y 1852.

Los gastos durante la Hambruna fueron un total de £8 millones; £7 millones de los impuestos irlandeses y £1 millón de los terratenientes, que constituye entre el 2 y el 3% del total del gasto público del Gobierno durante esos años.

Algunos académicos dudan si el pobre estado financiero de Gran Bretaña podría haber permitido un gasto mayor, pero, a su vez, tenemos los datos de que el Gobierno estaba invirtiendo £100 millones en una guerra con el Imperio otomano en esos mismos años.

.

Así que... se podría decir que la cita de John Mitchel no va muy desencaminada.

Aunque aquí tenéis los datos para juzgar.

Podría continuar con más datos sobre la Hambruna, como el tema de la migración, o incluso el preludio y los efectos posteriores (que también están incluidos en el libro del que saco la mayor parte de la información), o incluso añadir algunas de las «bonitas» citas que los diferentes miembros del Gobierno británico tenía dedicaban a los irlandeses en esas etapas tan duras, pero yo creo que esto es suficiente.

Con los simples hechos presentados de una forma objetiva —como en el libro—, basta. O eso creo.

Mañana seguramente publicaré el Glosario de enfermedades y daré por zanjado este fic.

#el retrato de una dama irlandesa#historia#history#ireland#irlanda#irish famine#gran hambruna irlandesa

1 note

·

View note

Text

What was the Irish Potato famine and why does it matter?

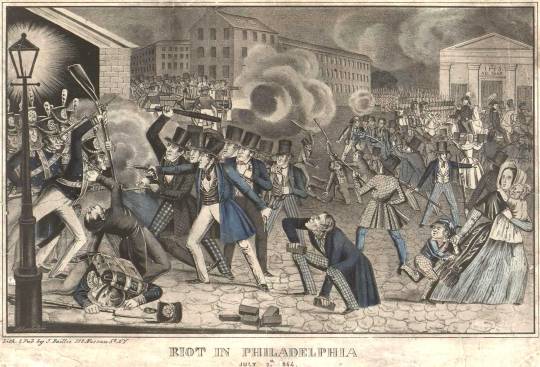

Anti-Irish riot in Philadelphia in 1841, Lithograph by H. Bucholzer in 1844.

Many have written about the Irish Potato Famine, which some call the Great Famine or Great Hunger. Most seem to agree it began in 1845, although some say it ended in 1849, and others say it ended in 1850, 1851 or 1852. [1] Some say the causes were due to the fact that "most of the Irish countryside was owned by an English and Anglo-Irish hereditary ruling class"and most were "absentee landlords that set foot on their properties once or twice a year, if at all," while the average tenant farmer, like John Mills, lets say, "lived at a subsistence level on less than ten acres...there was never any incentive to upgrade their living conditions," and they often allowed "landless laborers, known as cottiers, to live on their farms," with poor Irish laborers becoming "totally dependent on the potato for their existence." Others, like Harry George, said that "...at the period of her greatest population (1840-45) Ireland contained something over eight millions of people" but a large "proportion of them managed merely to exist, lodging in miserable cabins, clothed with miserable rags, and with but potatoes for their staple food" and when the "potato blight came, they died by thousands" not due to the "inability of the soil to support so large a population" but it was a "horde of landlords, among whom the soil had been divided as their absolute possession, regardless of any rights of those who lived upon it." He also wrote something, trying to disprove the Malthusian theory, that

Consider the conditions of production under which this eight million managed to live until the potato blight came. Cultivation was for the most part carried on by tenants-at-will, and they, even if the rack-rents they were forced to pay had permitted them, did not dare to make improvements, which would have been but the signal for an increase of rent. Labour was thus applied in the most inefficient and wasteful manner and labour, that with any security for its fruits would have been applied unremittingly, was dissipated in aimless idleness. But even under these conditions, it is a matter of fact that Ireland did more than support eight millions. For when her population was at its highest, Ireland was a food-exporting country. Even during the famine, grain and meat and butter and cheese were carted for exportation along roads lined with the starving and past trenches into which the dead were piled. For these exports of food, or at least for a great part of them, there was no return. So far as the people of Ireland were concerned, the food thus exported might as well have been burned up or thrown into the sea, or never produced. It went not as an exchange, but as a tribute - to pay the rent of absentee landlords; a levy wrung from producers by those who in no wise contributed to production. Had this food been left to those who raised it, had the cultivators of the soil been permitted to retain and use the wealth their labour produced, had security stimulated industry and permitted the adoption of economical methods, there would have been enough to support in bounteous comfort the largest population Ireland ever had. The potato blight might have come and gone without stinting a single human being of a full meal. For it was not, as English economists coldly said, "the imprudence of Irish peasants" that induced them to make the potato the staple of their food. Irish emigrants, when they can get other things, do not live upon the potato, and certainly in the United States the prudence of the Irish character, in endeavouring to lay by something for a rainy day, is remarkable. They lived on the potato because rack-rents stripped everything else from them. Had Ireland been by nature a grove of bananas and bread-fruit, had her coasts been lined by the guano deposits of the Chinchas and the sun of lower latitudes warmed into more abundant life her moist soil, the social conditions that have prevailed there would still have brought forth poverty and starvation. How could there fail to be pauperism and famine in a country where rack-rents wrested from the cultivator of the soil all the produce of his labour except just enough to maintain life in good seasons; where tenure-at-will forbade improvements and removed incentive to any but the most wasteful and poverty-stricken culture; where the tenant dared not accumulate capital, even if he could get it, for fear the landlord would demand it in the rent; where in fact he was an abject slave who, at the nod of a human being like himself, might at any time be driven from his miserable mud cabin, a houseless, homeless, starving wanderer, forbidden even to pluck the spontaneous fruits of the earth, or to trap a wild hare to satisfy his hunger? No matter how sparse its population, no matter what its natural resources, would not pauperism and starvation be necessary consequences in any land where the producers of wealth were compelled to work under conditions which deprived them of hope, of self-respect, of energy, of thrift; where absentee landlords drained away without return at least a fourth of the net produce of the soil; and when, besides them, a starving industry had to support resident landlords, with their horses and hounds, agents, jobbers, middlemen and bailiffs, and an army of policemen and soldiers to overawe and hunt down any opposition to the iniquitous system?

Others said it was related to a monoculture. Some readers may say that this doesn't matter based on the fact that Margaret Bibby and John Mills came before the famine began, likely in the early to mid 1830s, varied years before any famines. Although, considering the famines in 1830-1834, 1836, and 1839, which I talk about below, this may have been a favor. However, this does matter because at least some Mills family members were undoubtedly effected by this event.

This post was originally published on WordPress in June 2018.

Famine was nothing new to Ireland. It has been "common in Ireland in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries—for example in 1740–41 (bliain an áir ‘the year of the slaughter’), 1756–7, 1800, 1807, 1821–2, 1830–34, 1836, and 1839—but it was also common elsewhere in Europe," with the western seaboard the worst affected. But what began in 1845, ending possibly in 1852, was a horrible catastrophe, which the government failing to deal with the problem, leading to further crisis. Some say that with the "devastating fungus destroyed Ireland's potato crop," leading to "starvation and related diseases," over hundreds of thousands, if not a million, may have been killed, with others blaming capitalism as the cause of what happened.

Regardless of what you blame, the reality is that there was a strong population decline from 1841 to 1851 in Ireland, changing the social and cultural structure of the island as a whole. In the process, however, the landscape of parts of the U.S. was changed as well from incoming Irish immigrants, as 3/4 of those who left Ireland came to the U.S. The heart of Ireland's economy had been sunk. But, Irish history was to go on.

With the information about Ireland's other famines, specifically the ones 1830-1834, 1836, and 1839, before the "potato famine" beginning in 1845, it could help us answer some of the the remaining questions, determining more push and pull factors from County Tipperary in Southern Ireland, connect to the stories of John and Margaret's children, and down the line.

© 2018-2023 Burkely Hermann. All rights reserved.

Notes

[1] Joel Mokyr, "Great Famine," Encyclopaedia Brittanica, accessed May 11, 2018; "Sources in the National Archives for researching the Great Famine by Marianne Cosgrave, Rena Lohan and Tom Quinlan: Introduction," National Archives of Ireland, Sept 1995; Brian McDonald, "British fail to attend Famine ceremony," Independent, May 17, 2010; "The Irish in Philadelphia"; "Fertility trends, excess mortality, and the Great Irish Famine"; John Gibney, "Where was your family during the famine?," Sept 2008; "The Great Irish Famine," Nov 1998; Dan Ritschel, "The Irish Famine: Interpretative and Historiographical Issues," 2009; Mark Ward, "Irish Repay Choctaw Famine Gift: March Traces Trail of Tears in Trek for Somalian Relief," American-Stateman Capitol Staff, 1992; Jim Donnelly, "The Irish Famine," BBC, Feb 17, 2011; "The Irish Potato Famine," Digital History, 2016; Eleanor Bley Griffiths, "What was the Irish Potato Famine?," RadioTimes, May 11, 2018.

#irish#anti irish#irish heritage#irish americans#irish famine#potato famine#history#irish genalogy#wordpress#19th century#1830s#1840s#1850s

1 note

·

View note