#kodak eastman

Text

descent | Olympus OM-1 | Kodak Eastman 250 | 2022

#daniloz#analog photography#35mm#nature#35mm film#35mm photography#kodak#olympus om1#olympus photography#bird#egret#motion#kodak bw#bw film#bw photography#kodak eastman#farm#zuiko lens

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kodak logo, 1971.

Designer: Peter Oestreich

446 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kodachrome Film advertisement (1942).

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm going through the complete text of Dracula to try and determine what year it takes place based on the days of the week mentioned by the characters.

The novel can be set no earlier than 1888, as that was the year the Kodak camera Jonathan uses was invented, though the Eastman Kodak company wasn't formally organized until May 1892, so we're really looking at 1893 as the lower bound.

Arthur and Quincey go home after Lucy's funeral on 22 September, and on the 26 September Dr. Seward receives a letter from them dated Sunday, which must have fallen on 23, 24, or 25.

Sunday, 23 September, 1888 [this year is too early]

Sunday, 25 September, 1892 [too early]

Sunday, 24 September, 1893

Sunday, 23 September, 1894

Sunday, 25 September, 1898

Sunday, 24 September, 1899

Sunday, 23 September, 1900

Note: the novel was published in 1897, but all we know is that it takes place in the 19th century (Jonathan says so on 15 May, Seward on 26 September, and Van Helsing on 30 September), so 1898, 1899, and 1900 are not necessarily disqualified. This gives us upper and lower bounds of 1888 - 1900, or more likely 1893 - 1900

Spoiler for events that haven't been emailed yet: on 2 November, Jonathan writes in his journal that Mina and Van Helsing should have arrived in Veresti around noon on Wednesday. A few pages later, Mina's own journal says they arrived at Veresti noon on 31 October.

Wednesday, 31 October, 1888 [too early]

Wednesday, 31 October, 1894

Wednesday, 31 October, 1900

Lucy's very first letter to Mina is not dated, but is said to have been written on a Wednesday. Dracula Daily emailed it on 11 May, but only because that happened to be a Wednesday in 2022. Mina's previous letter to Lucy was dated 9 May, and subsequent letters between the group tend to be delivered very quickly, so let's look for Wednesdays that were less than, say, four days after 9 May

Wednesday, 13 May, 1891 [too early]

Wednesday, 11 May, 1892 [too early]

Wednesday, 10 May, 1893

Wednesday, 13 May, 1896

Wednesday, 12 May, 1897

Wednesday, 11 May, 1898

Wednesday, 10 May, 1899

On 25 September, Mina tells Van Helsing that Jonathan nearly fainted last Thursday when he saw a man that looked like a young Count Dracula. She recorded this episode in her diary three days prior.

Thursday, 22 September, 1892 [too early]

Thursday, 22 September, 1898

A newspaper clipping dated 8 August says that the big storm that hit Whitby came out of nowhere, and that Saturday evening had been as calm as any other. On 6 August, Mina wrote that the day was gray and fishermen were warning people that a storm was brewing. If Saturday evening was calm, but Mina reported gray skies on the 6th, then either she wrote about it late on Saturday after the storm started rolling in, or sometime on Sunday, meaning Saturday is either 5 or 6 August.

Saturday, 6 August, 1892 [too early]

Saturday, 5 August, 1893

Saturday, 6 August, 1898

Saturday, 5 August, 1899

Those are all the days of the week mentioned in the book, so now let's account for the phases of the Moon. Mina says it was full at 3am on 11 August. Full moons rise at sunset, so it would have risen on the 10th. Looking at a phase calendar, let's say a reasonable person in the 1890s would say it looks full for 2 days before or 2 days after the actual full moon (3 days, and you start to notice it waxing and waning). When did the full moon fall between 10 and 13 August?

Saturday, 10 August, 1889 (looks full from 8 - 12) [too early]

Monday, 8 August, 1892 (looks full 6 - 10) [too early]

Thursday, 12 August, 1897 (looks full 10 - 14)

Friday, 10 August, 1900 (looks full 8 - 12)

Dr. Seward says that there was "full moonlight" on 20 September, the night Lucy died. That's more than a month after Mina's full moon, but Seward didn't actually go outside to check, he just noticed the moonlight through the window, so let's give him some more wiggle room and say that the moonlight could appear bright enough to be mistaken for full up to 4 days before and after the actual full moon; it's about one week between the quarter and full phases, and nobody could mistake a quarter moon's light for being full, but I guess you could make that mistake for a gibbous moon if you don't see it directly. When did the full moon fall between 16 and 24 September?

Thursday, 20 September, 1888 (seems full 16 - 24) [too early]

Friday, 18 September, 1891 ("full" 14 - 22) [too early]

Monday, 25 September, 1893 ("full" 21 - 29; kind of a stretch)

Monday, 21 September, 1896 ("full" 17 - 25)

Tuesday, 19 September, 1899 ("full" 15 - 23)

Let's tally up all the data

1888: 3

1889: 1

1890: 0

1891: 2

1892: 5

1893: 3.5

1894: 2

1895: 0

1896: 2

1897: 2

1898: 4

1899: 4

1900: 3

No year won all 7 possible points, so there's no doubt that Bram Stoker was just making up the timeline as he went along; he didn't have calendars and moon charts open as he was writing, so he fudged some details because he figured nobody would ever attempt to put the story in chronological order. That said, the year that fits best would be 1892 were it not for the fact that the Kodak company was brand new in May 1892, so it's unlikely a British law firm would supply their solicitors with American cameras before they became ubiquitous. 1898 and 1899 come in second, and are therefore the most plausible for the novel's setting; if we ignore the moon, 1898 wins with 4 points to 3. I however choose to set the novel in 1894 because that would place the epilogue in 1901, just over the hump of the 20th century, which is fitting, but really you could argue for any years except 1890 and 1895.

#dracula#dracula daily#bram stoker#1890s#1800s#19th century#timeline#kodak#eastman kodak#1892#1893#1894#1896#1897#1898#1899#1900#days of the week#reconciliation

168 notes

·

View notes

Text

Forward we move, upward we climb

Nikkormat FTN

Nikkor 35-70mm f/3.3-4.5

Kodak Eastman Double-X (5222) @ 200

Rodinal 1:50 (9mins)

Tumblr - Instagram

#35mm#analog#nikkormat#nikkor#kodak#eastman#double x#rodinal#home developed film#explore nature#bnw film#film photo#landscape#original photography#photographers on tumblr#blu27nature

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

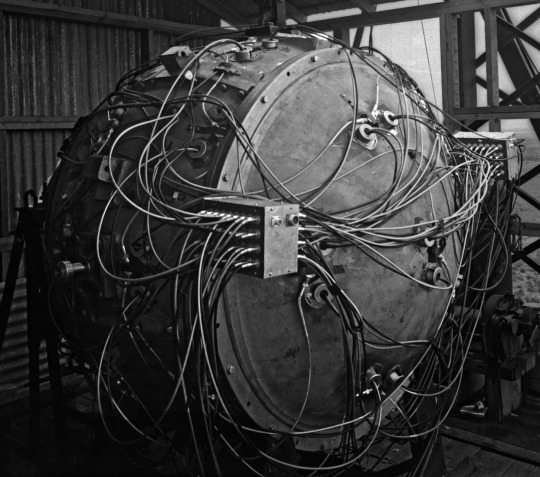

The First Light of Trinity

— By Alex Wellerstein | July 16, 2015 | Annals of Technology

Seventy years ago, the flash of a nuclear bomb illuminated the skies over Alamogordo, New Mexico. Courtesy Los Alamos National Laboratory

The light of a nuclear explosion is unlike anything else on Earth. This is because the heat of a nuclear explosion is unlike anything else on Earth. Seventy years ago today, when the first atomic weapon was tested, they called its light cosmic. Where else, except in the interiors of stars, do the temperatures reach into the tens of millions of degrees? It is that blistering radiation, released in a reaction that takes about a millionth of a second to complete, that makes the light so unearthly, that gives it the strength to burn through photographic paper and wound human eyes. The heat is such that the air around it becomes luminous and incandescent and then opaque; for a moment, the brightness hides itself. Then the air expands outward, shedding its energy at the speed of sound—the blast wave that destroys houses, hospitals, schools, cities.

The test was given the evocative code name of Trinity, although no one seems to know precisely why. One theory is that J. Robert Oppenheimer, the head of the U.S. government’s laboratory in Los Alamos, New Mexico, and the director of science for the Manhattan Project, which designed and built the bomb, chose the name as an allusion to the poetry of John Donne. Oppenheimer’s former mistress, Jean Tatlock, a student at the University of California, Berkeley, when he was a professor there, had introduced him to Donne’s work before she committed suicide, in early 1944. But Oppenheimer later claimed not to recall where the name came from.

The operation was designated as top secret, which was a problem, since the whole point was to create an explosion that could be heard for a hundred miles around and seen for two hundred. How to keep such a spectacle under wraps? Oppenheimer and his colleagues considered several sites, including a patch of desert around two hundred miles east of Los Angeles, an island eighty miles southwest of Santa Monica, and a series of sand bars ten miles off the Texas coast. Eventually, they chose a place much closer to home, near Alamogordo, New Mexico, on an Army Air Forces bombing range in a valley called the Jornada del Muerto (“Journey of the Dead Man,” an indication of its unforgiving landscape). Freshwater had to be driven in, seven hundred gallons at a time, from a town forty miles away. To wire the site for a telephone connection required laying four miles of cable. The most expensive single line item in the budget was for the construction of bomb-proof shelters, which would protect some of the more than two hundred and fifty observers of the test.

The area immediately around the bombing range was sparsely populated but not by any means barren. It was within two hundred miles of Albuquerque, Santa Fe, and El Paso. The nearest town of more than fifty people was fewer than thirty miles away, and the nearest occupied ranch was only twelve miles away—long distances for a person, but not for light or a radioactive cloud. (One of Trinity’s more unusual financial appropriations, later on, was for the acquisition of several dozen head of cattle that had had their hair discolored by the explosion.) The Army made preparations to impose martial law after the test if necessary, keeping a military force of a hundred and sixty men on hand to manage any evacuations. Photographic film, sensitive to radioactivity, was stowed in nearby towns, to provide “medical legal” evidence of contamination in the future. Seismographs in Tucson, Denver, and Chihuahua, Mexico, would reveal how far away the explosion could be detected.

The Trinity test weapon. Courtesy Los Alamos National Laboratory

On July 16, 1945, the planned date of the test, the weather was poor. Thunderstorms were moving through the area, raising the twin hazards of electricity and rain. The test weapon, known euphemistically as the gadget, was mounted inside a shack atop a hundred-foot steel tower. It was a Frankenstein’s monster of wires, screws, switches, high explosives, radioactive materials, and diagnostic devices, and was crude enough that it could be tripped by a passing storm. (This had already happened once, with a model of the bomb’s electrical system.) Rain, or even too many clouds, could cause other problems—a spontaneous radioactive thunderstorm after detonation, unpredictable magnifications of the blast wave off a layer of warm air. It was later calculated that, even without the possibility of mechanical or electrical failure, there was still more than a one-in-ten chance of the gadget failing to perform optimally.

The scientists were prepared to cancel the test and wait for better weather when, at five in the morning, conditions began to improve. At five-ten, they announced that the test was going forward. At five-twenty-five, a rocket near the tower was shot into the sky—the five-minute warning. Another went up at five-twenty-nine. Forty-five seconds before zero hour, a switch was thrown in the control bunker, starting an automated timer. Just before five-thirty, an electrical pulse ran the five and a half miles across the desert from the bunker to the tower, up into the firing unit of the bomb. Within a hundred millionths of a second, a series of thirty-two charges went off around the device’s core, compressing the sphere of plutonium inside from about the size of an orange to that of a lime. Then the gadget exploded.

General Thomas Farrell, the deputy commander of the Manhattan Project, was in the control bunker with Oppenheimer when the blast went off. “The whole country was lighted by a searing light with the intensity many times that of the midday sun,” he wrote immediately afterward. “It was golden, purple, violet, gray, and blue. It lighted every peak, crevasse, and ridge of the nearby mountain range with a clarity and beauty that cannot be described but must be seen to be imagined. It was that beauty the great poets dream about but describe most poorly and inadequately.” Twenty-seven miles away from the tower, the Berkeley physicist and Nobel Prize winner Ernest O. Lawrence was stepping out of a car. “Just as I put my foot on the ground I was enveloped with a warm brilliant yellow white light—from darkness to brilliant sunshine in an instant,” he wrote. James Conant, the president of Harvard University, was watching from the V.I.P. viewing spot, ten miles from the tower. “The enormity of the light and its length quite stunned me,” he wrote. “The whole sky suddenly full of white light like the end of the world.”

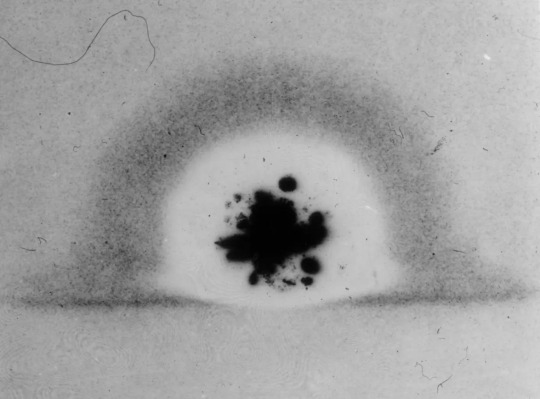

In its first milliseconds, the Trinity fireball burned through photographic film. Courtesy National Archives and Records Administration

Trinity was filmed exclusively in black and white and without audio. In the main footage of the explosion, the fireball rises out of the frame before the cameraman, dazed by the sight, pans upward to follow it. The written accounts of the test, of which there are many, grapple with how to describe an experience for which no terminology had yet been invented. Some eventually settle on what would become the standard lexicon. Luis Alvarez, a physicist and future participant in the Hiroshima bombing, viewed Trinity from the air. He likened the debris cloud, which rose to a height of some thirty thousand feet in ten minutes, to “a parachute which was being blown up by a large electric fan,” noting that it “had very much the appearance of a large mushroom.” Charles Thomas, the vice-president of Monsanto, a major Manhattan Project contractor, observed the same. “It looked like a giant mushroom; the stalk was the thousands of tons of sand being sucked up by the explosion; the top of the mushroom was a flowering ball of fire,” he wrote. “It resembled a giant brain the convolutions of which were constantly changing.”

In the months before the test, the Manhattan Project scientists had estimated that their bomb would yield the equivalent of between seven hundred and five thousand tons of TNT. As it turned out, the detonation force was equal to about twenty thousand tons of TNT—four times larger than the expected maximum. The light was visible as far away as Amarillo, Texas, more than two hundred and eighty miles to the east, on the other side of a mountain range. Windows were reported broken in Silver City, New Mexico, some hundred and eighty miles to the southwest. Here, again, the written accounts converge. Thomas: “It is safe to say that nothing as terrible has been made by man before.” Lawrence: “There was restrained applause, but more a hushed murmuring bordering on reverence.” Farrell: “The strong, sustained, awesome roar … warned of doomsday and made us feel that we puny things were blasphemous.” Nevertheless, the plainclothes military police who were stationed in nearby towns reported that those who saw the light seemed to accept the government’s explanation, which was that an ammunition dump had exploded.

Trinity was only the first nuclear detonation of the summer of 1945. Two more followed, in early August, over Hiroshima and Nagasaki, killing as many as a quarter of a million people. By October, Norris Bradbury, the new director of Los Alamos, had proposed that the United States conduct “subsequent Trinity’s.” There was more to learn about the bomb, he argued, in a memo to the new coördinating council for the lab, and without the immediate pressure of making a weapon for war, “another TR might even be FUN.” A year after the test at Alamogordo, new ones began, at Bikini Atoll, in the Marshall Islands. They were not given literary names. Able, Baker, and Charlie were slated for 1946; X-ray, Yoke, and Zebra were slated for 1948. These were letters in the military radio alphabet—a clarification of who was really the master of the bomb.

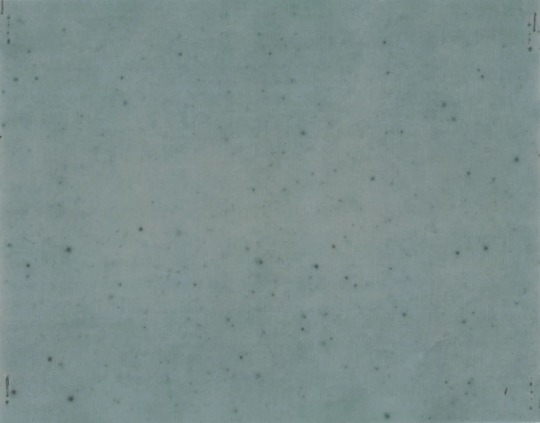

Irradiated Kodak X-ray film. Courtesy National Archives and Records Administration

By 1992, the U.S. government had conducted more than a thousand nuclear tests, and other nations—China, France, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union—had joined in the frenzy. The last aboveground detonation took place over Lop Nur, a dried-up salt lake in northwestern China, in 1980. We are some years away, in other words, from the day when no living person will have seen that unearthly light firsthand. But Trinity left secondhand signs behind. Because the gadget exploded so close to the ground, the fireball sucked up dirt and debris. Some of it melted and settled back down, cooling into a radioactive green glass that was dubbed Trinitite, and some of it floated away. A minute quantity of the dust ended up in a river about a thousand miles east of Alamogordo, where, in early August, 1945, it was taken up into a paper mill that manufactured strawboard for Eastman Kodak. The strawboard was used to pack some of the company’s industrial X-ray film, which, when it was developed, was mottled with dark blotches and pinpoint stars—the final exposure of the first light of the nuclear age.

#Hiroshima | Japan 🇯🇵 | John Donne | Manhattan Project | Monsanto#Nagasaki | Japan 🇯🇵 | Nuclear Weapons | Second World War | World War II#The New Yorker#Alex Wellerstein#Los Alamos National Laboratory#New Mexico#J. Robert Oppenheimer#John Donne#Jean Tatlock#University of California Berkeley#Jornada del Muerto | Journey of the Dead Man#General Thomas Farrell#Nobel Prize Winner Physicist Ernest O. Lawrence#Luis Alvarez#US 🇺🇸#China 🇨🇳#France 🇫🇷#Soviet Union (Now Russia 🇷🇺)#Alamogordo | New Mexico#Eastman Kodak#Nuclear Age

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eastman-Kodak Six-16 Camera Advertisement

National Geographic Magazine, December 1934

#vintage#advertising#advertisement#vintage ads#1930s#30s#1934#kodak#eastman-kodak#eastman#vintage camera#film camera

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Eastman Kodak No. 2 Folding Autographic Brownie - folding camera for type 120 autographic film. More than half a million models were sold between 1915 and 1926.

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

Whoever came up with the "holds pen up as proof" moment when Joel's pretending to be a scholar from the local university is the funniest person on earth.

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#black and white#photography#analog photography#35 mm#leica m3#elmar 50 mm 2.8#hc-110#kodak eastman double-x

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

reflection | Olympus OM-1 | Kodak Eastman double X 250 | 2022

#daniloz#analog photography#analog 35mm#35mm#35mm film#35mm photography#bw photography#bw film#35mm BW#reflection#lake#tree#farm#olympus om-1#m.zuiko#olympus photography#kodak#kodak eastman double x#Kodak Eastman#kodak bw

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

George Eastman Museum, Rochester, N.Y., 2023

Photo: Bruce Morrow

#the moment that we are today#the moment that#bruce morrow#art#brucemorrow#bruce-morrow#digital art#nft digital art#my art#myart#george eastman#George Eastman museum#rochester#ny#Kodak#on iPhone#iphone#themomentthat

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

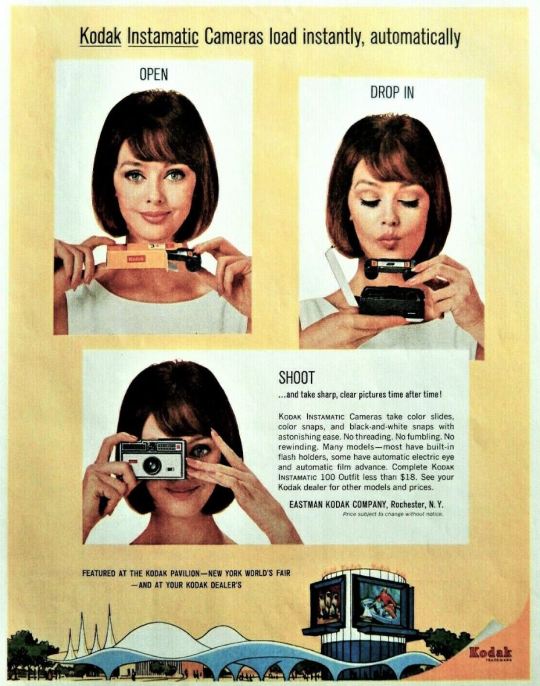

Advertisement for Kodak Instamatic cameras (1964).

#vintage advertisement#kodak#1960s#camera#kodak instamatic#photography#film#cameras#usa#eastman kodak

138 notes

·

View notes

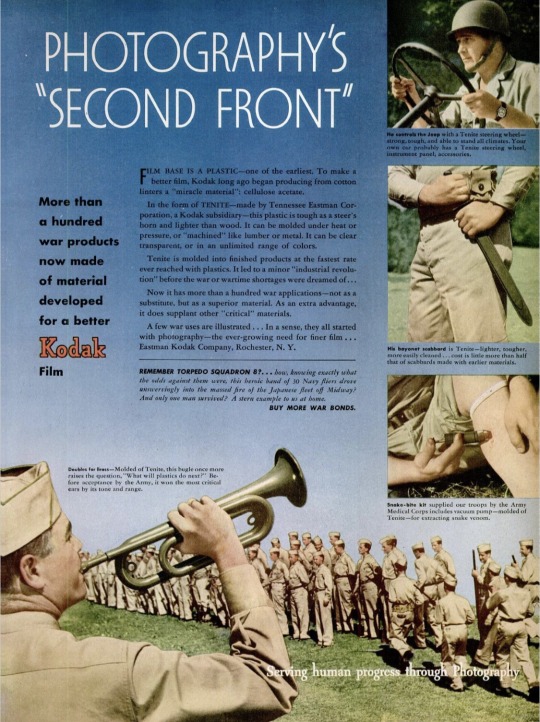

Text

1944 Wartime Kodak advertising

#1944#Kodak#eastman kodak#photography#camera#vintageadsmakemehappy#vintage magazine#vintage advertising#magazine#advertising#wwii#ww2#world war 2#wartime#40s#1940s

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

quick! in the tags: favourite "low key vacation spot"

(as in, you'd go there for long weekends, or is somewhere that when you say you'd go there on vacations, people go "... why?")

#mine is rochester NY#it's close to home#it has some cool things to see#but it's also across the border so US junk food <33#side note: cool things to check out include the strong museum of play#and the eastman kodak house. and the house of guitars#vacations#in the tags

4 notes

·

View notes