#mexican american war

Photo

Mexican-American war

by srb_maps

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

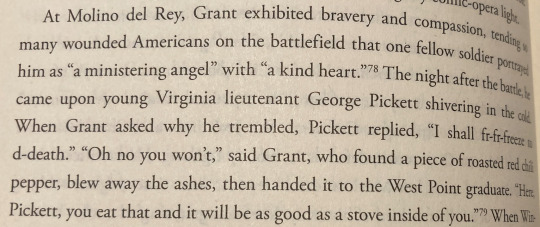

AISUCBHIUASBHCIASB THIS IS ONE OF THE FUNNIEST THINGS I'VE READ IN A BOOK (Grant by...Ron Chernow)

I never knew they met but I'm so glad they did. Canon interaction between faves 🫶

WHY IS THE DIALOGUE LIKE THAT?!?!? IT'S LIKE CHERNOW IS WRITING WATTPAD FANFICTION.

WHY DOESN'T IT SAY IF HE ATE IT OR NOT! I WILL JUST ASSUME HE DID BECAUSE IT'S SILLY!

THIS IS LIKE A CROSS BETWEEN A PRANK AND GENUINE ADVICE. If anyone was to be pranked by Grant I find it absolutely hilarious that it's Pickett. 😭😭😭

udbcfiuwebdfciw knowing Pickett was an idiot (affectionate), he probably ate it. As a white southerner he probably thought he was dying, like when Aaron Burr got a brain-freeze oiwrfnisdf. I just imagine him standing there, suffering djabciaudbfaed.

This scene keeps playing in my head

Pickett: I-I'm going t-to freeze to d-death

Grant: Oh no you don't *feeds him a pepper*

Pickett: *collapses, coughing*

Grant: *looks into camera smirking*

Grant:

This paragraph has changed my life. I will never ever sleep soundly again.

Both of them 🫶

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

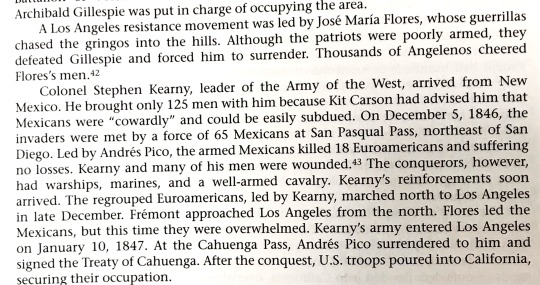

The “founding” of Los Angeles.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

A War of Misinformation

Public School taught me that the Mexican-American war was an intervention. To save the country from a dictator, Santa Anna. The US Army rallied to save the oppressed people of Mexico as Santa Anna had taken Texas by force.

Counterpoint: The Mexican-American War was a war supported by false and misconstrued information.

Santa Anna had rallied an army to take Texas. These 300 families of Austin would not stop importing slaves into Texas. The problem is that slavery was illegal in Mexico. Yet these American immigrants insisted upon it despite Mexico's stance.

Mexico would offer opportunities for emancipation. They banned the purchasing and selling of people in 1823. Mexico also passed a law that gave blacks born in Mexico automatic citizenship. This meant that these Anglo-Texan immigrants wouldn't be able to own a slave's child. A custom often practiced in the United States. Yes, if you were a slave and had children, they weren't your children. They were your master's children.

If you're familiar with Reactionary sentiment, they don't take too well to the word "no." So to make concessions for these adult toddlers, Mexico exempted Texas. Texans could own slaves until 1830. The abolitionist sentiment was prevalent within Mexico. It was so prevalent that slavers would force slaves to sign contracts. "No, no they weren't slaves. They were working to pay their debt off."

What I am saying is that if you had to report the crime rate in Texas around the 1830s. White American immigrants would be the biggest sources of crime. They were a backward group of people. While Mexico progressed and attempted to dismantle slavery, White Americans would insist. They would insist upon their draconian and archaic customs despite their surrounding conditions. Would defy the face of a modernizing world in favor of their Manifest Destiny. Manifest Destiny, a crusade against non-Americans. The goal is to gain exclusive ownership of land by any means necessary. Yet it was Mexico who needed an intervention?

I'm only pointing out that some more Conservative media outlets will demonize Mexicans. Some older sources would demonize Catholics. Yet it was Mexicans that founded a country that would abolish slavery before the US.

Slavery was a practice that was becoming irrelevant in the mid-19th century. A practice that would become an issue that killed millions of Americans in a civil war. Yet Mexico needed the intervention?

Because American immigrants were becoming the biggest source of crime in Mexico. Mexican Congress took action to enforce its abolition policy. Congress would reintroduce property taxes which discouraged further immigration. Import Tariffs would slam down on American-imported products. If you're going to insist upon your archaic practice, you can at least pay for it. It's not like you're paying your slaves.

In response, the Texans would declare independence from a country they immigrated to. So yes, Santa Anna brought an Army to suppress an insurrection in Mexico’s country. If Mexicans tried to do the same thing in Texas, New Mexico, or Arizona, the response would be just as forceful. Tucker Carlson would be freaking out in an “I’m not racist but” line of dialogue.

Douglas Hales, "Free Blacks", Handbook of Texas Online, accessed 12 Aug 2009

Douglas W. Richmond, "Vicente Guerrero" in Encyclopedia of Mexico, Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997, p. 617. Santoni, "U.S.-Mexican War", p. 1511.

After Santa Anna had taken the Alamo, the Texans would defeat and capture him. This was what these terrorists explained to Santa Anna. Sign the treaty to confirm Texas' sovereignty or get shot. Under duress, Santa Anna would sign the treaty. Now, remember: U.S. propaganda portrays the Mexican Army as bloodthirsty or cruel. They would never surrender or see reason.

So Santa Anna signing the treaty is quite uncharacteristic to what the US said. James Polk insisted that the bloodthirsty Mexicans came over to shoot them. That they only wanted war and conquest, like their Conquistador ancestors. I'm joking, I doubt most Americans could pronounce Conquistador.

Santa Anna brought this treaty back to Mexican Congress. Congress denied this treaty. Now, if you're following American propaganda, of course they denied it. Those bastards will never give up. They're sneaky and two-faced and only want American blood...no, that's not what Congress said.

Yes, many express frustrations about rebels taking Mexican territory that wasn't theirs. The main reason are the conditions in which the treaty took place. Santa Anna signing the treaty was not the negotiation of two nations. Santa Anna signing the treaty had done so ONLY by threat of force. You'll find the United States using this method for many more "treaties." This treaty was not a treaty validated by two nations, this was a hostage situation.

On top of that, the Texas Revolution wouldn't stop in Texas. These militias would send excursions into Arizona and New Mexico which. The Mexican Army had thwarted. Oh...and as far as Santa Anna being this totalitarian snake who ruled Mexico with an iron fist.

The Presidency had changed 4 times, the War Ministry 6 times, and the Finance Ministry 16. Mexico was a volatile country at this point. Politics were getting heated and it was affecting the people living within it. One thing that did unite Mexican politicians was the cession of Texas. They weren't willing to do it. As far as they're concerned, the militias are terrorists fighting for slavery.

Donald Fithian Stevens, Origins of Instability in Early Republican Mexico (1991), p. 11.

Rives, George Lockhart (1913). The United States and Mexico, 1821–1848: a history of the relations between the two countries from the independence of Mexico to the close of the war with the United States. Vol. 2. New York: C. Scribner's Sons.

James Polk decided that the U.S. should go to war with Mexico. It was not a popularly-supported decision at the beginning. Many members of the Whig Party were abolitionists. They knew that by accepting Texas as a part of the United States, Texas would come in as a Pro-Slavery territory.

The Democrats held a strong belief in Manifest Destiny, citing it as a reason to take Texas. The Monroe Doctrine was a policy motivated by Manifest Destiny. This doctrine would claim dibs on North America. This was in response to European powers encroaching on modern-day Oregon. The United States didn't want to contend with European Empires for the land they wanted. Manifest Destiny was a sense of entitlement for these White Americans. God himself had defined this land as theirs. This nationalist mythology would set the West Coast as the final destination. As the world knows, that wouldn't be the end of American exceptionalism.

The Whig opposition to the war wouldn't last. Senators like John Quincy Adams and Abraham Lincoln would debate the validity of the war. Lincoln went as far as to ask Polk for the exact location of the skirmish. Can Polk point out on a map where the Mexican soldiers shot the Texan settlers? If these was to be a cassus beli, the least he could do is provide proof. Polk couldn't produce the proof, so him and his War Hawks turned to more misinformation.

Despite the anti-war rhetoric, the Whigs would vote for the war. Good to know that politicians voted for war even back in 1840. It's a relief to know that politicians then weren't any different than now. So when one says "this is the worst it's ever been" it wasn't. We have fancier toys, but the human condition is still the same.

There were some principled people against the war and they weren’t politicians. Law enforcement arrested Henry David Thoreau for refusing to pay a tax for the war effort. He wrote an essay known as Civil Disobedience, an influential work.

See O'Sullivan's 1845 article "Annexation" Archived November 25, 2005, at the Wayback Machine, United States Magazine and Democratic Review. https://xroads.virginia.edu/~Hyper2/thoreau/civil.html

“I heartily accept the motto, "That government is best which governs least"; and I should like to see it acted up to more rapidly and systematically. Carried out, it finally amounts to this, which also I believe- "That government is best which governs not at all"; and when men are prepared for it, that will be the kind of government which they will have. Government is at best but an expedient; but most governments are usually, and all governments are sometimes, inexpedient. The objections which have been brought against a standing army, and they are many and weighty, and deserve to prevail, may also at last be brought against a standing government. The standing army is only an arm of the standing government. The government itself, which is only the mode which the people have chosen to execute their will, is equally liable to be abused and perverted before the people can act through it. Witness the present Mexican war, the work of comparatively a few individuals using the standing government as their tool; for, in the outset, the people would not have consented to this measure.”

I'd recommend further reading. In another part he compares voting to wishing for change to happen instead of being the change. This essay would influence Martin Luther King Jr and Gandhi. It would also influence lesser-known figures like Alice Pauls. Pauls had campaigned for Women's Suffrage in the United States. This essay also influenced Tolstoy when he wrote War and Peace. It inspired Upton Sinclair when he exposed the lack of sanitation in meat packing.

Maynard, W. Barksdale, Walden Pond: A History. Oxford University Press, 2005 (p. 265). .

My point on leaving this on Civil Disobedience. Many feel limited by their surrounding conditions. It's very easy to do. The United States would commit the public to a war of annexing Mexican territory. It's because they didn't do enough to counter the misinformation. It's because we fear we'll waste our time. We treat our nations as if we have no stake in them. We treat the politicians as another body separate from the people. We slump our heads thinking the nation will act with or without our consent

The process of revolution is not narrowed down to a single war or battle. You can achieve a meaningful difference with a holistic approach. Revolution isn't only cannon fodder and blood. Revolution is a mindset. This is why nations try to censor information. This is why Propaganda exists. It doesn't exist to inform, but rather the opposite. If the collective knowledge of the public wasn't important it wouldn't receive funding. The United States defunds its education while pouring money into News outlets. Europe enacts vehement scapegoating of Reactionaries while riling anti-Russian sentiment.

They depend on our fear for us to do their bidding. Knowledge is an axe to these intentions. Debate is a grindstone to sharpen our axe. Groups and communities are the forges that provide us with the tools we need.

You are all capable of action. You're all brilliant in your ways. You'll devise solutions that nobody else can think of. Thomas Paine didn't fight one battle in the American Revolution. John Adams didn't have the Military career Alexander Hamilton did. It was Adams who chartered recognition from European powers.

American Council of Education. (2019, March 11). White House proposes significant cuts to education programs for FY 2020. News Room. Retrieved November 25, 2022, from https://www.acenet.edu/News-Room/Pages/White-House-Proposes-Significant-Cuts-to-Education-Programs-for-FY-2020.aspx

bureaus, M. V. I. A. T. T. E. A. U. with A. F. P. (2022, March 11). 'get the hell out': Wave of Anti-Russian sentiment in Europe. Barron's. Retrieved November 25, 2022, from https://www.barrons.com/news/get-the-hell-out-wave-of-anti-russian-sentiment-in-europe-01647018307

Camera, L. (2022, March 9). Congress set to cut funds that made school meals free - US news & world ... US News. Retrieved November 25, 2022, from https://www.usnews.com/news/education-news/articles/2022-03-09/congress-set-to-cut-funds-that-made-school-meals-free

Conte, M. (2021, December 8). US announces funds to support independent journalism and reporters targeted for their work | CNN politics. CNN. Retrieved November 25, 2022, from https://www.cnn.com/2021/12/08/politics/blinken-summit-democracy-journalism/index.html

Rob Portman Press Release. (2016, December 23). President signs Portman-Murphy Counter-propaganda bill into law. Senator Rob Portman. Retrieved November 25, 2022, from https://www.portman.senate.gov/newsroom/press-releases/president-signs-portman-murphy-counter-propaganda-bill-law

Ferling, John E. (1992). John Adams: A Life. Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 978-0-87049-730-8.

Thoreau argued against any revolution coming “too soon.” Be realistic, what can you finish? Acting reckless without real support does nothing but cause unnecessary risk. Finding truth outside propaganda is our responsibility. We'll inevitably fall prey to one form of propaganda. There are many factions we're a part of. This will come with many biases. Instead of denying bias, be cognizant of it when you approach a topic. Find out what's supported by fact and what's propped by bias.

Thoreau acted when the surrounding society wouldn’t substantiate his belief. This doesn’t make him wrong. You don't owe apathy a consideration. You don't owe a palatable approach to those that have a problem with your conviction. You will take the time to consider all angles while they only accept their confirmation bias. The time for apathy needs to meet its end. We can do so via a fervent pursuit of truth. Do not let them discourage you, keep marching. They'll pick a tune and flag to march to in the end.

Also, let me recommend Howard Zinn’s book People’s History of the United States. He does more justice to American history from the people’s perspective than I ever could.

The Chapter referring to the Mexican-American war is “Thank God it wasn’t taken by Conquest.”

Origins of Instability in Early Republican Mexico (1991), p. 11. Rives, George Lockhart (1913). The United States and Mexico, 1821–1848: a history of the relations between the two countries from the independence of Mexico to the close of the war with the United States. Vol. 2. New York: C. Scribner's Sons.

See O'Sullivan's 1845 article "Annexation" Archived November 25, 2005, at the Wayback Machine, United States Magazine and Democratic Review. https://xroads.virginia.edu/~Hyper2/thoreau/civil.html

Maynard, W. Barksdale, Walden Pond: A History. Oxford University Press, 2005 (p. 265). Ferling, John E. (1992). John Adams: A Life. Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 978-0-87049-730-8.

Origins of Instability in Early Republican Mexico (1991), p. 11. Rives, George Lockhart (1913). The United States and Mexico, 1821–1848: a history of the relations between the two countries from the independence of Mexico to the close of the war with the United States. Vol. 2. New York: C. Scribner's Sons. http://www.historyisaweapon.com/defcon1/zinntak8.html

#history#united states#united states of america#book recommendation#class warfare#imperialism#anti imperialism#mexico#mexican#mexican american war#manifest destiny#monroe doctrine#american history#civil disobedience#martin luther king jr#gandhi#slavery#abolition#education#no child left behind#campism#colonialism#social justice#texas#war and peace#Santa Anna#european union#europe#russia#propaganda

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Photo of John Fulton Reynolds, c. 1846

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

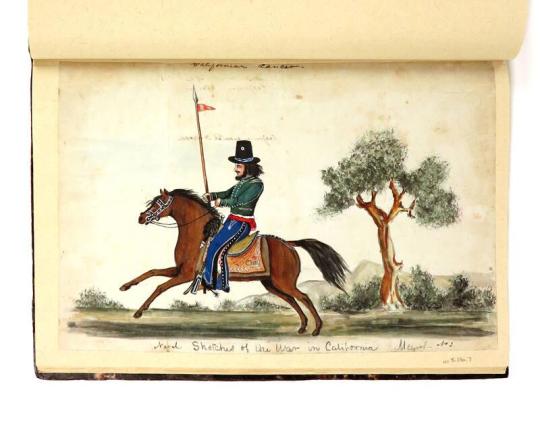

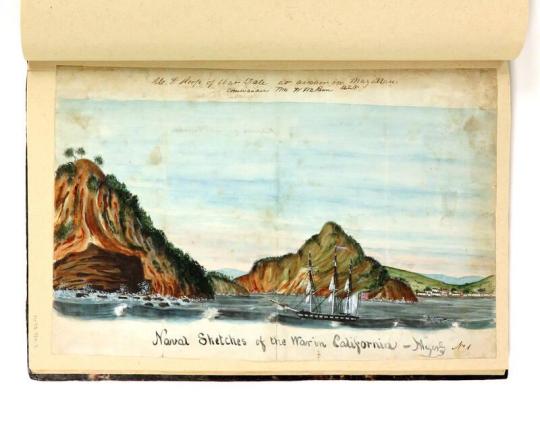

FDR The Naval Combat Art Collector

While he was governor of New York, Franklin D. Roosevelt purchased this original volume of drawings and sketches by William H. Meyers on August 18, 1930 for $900 from Francis D. Brinton. The artwork was considered the only known illustrations of an important phase of the 1846-1848 war with Mexico.

Born in Philadelphia in 1815, Meyers began his career in the United States Navy as an enlisted man and then worked as a civilian at the Washington Navy Yard before being appointed to the Warrant Officer rank of Gunner in 1841. Meyers served on board the sloop-of-war Dale during the naval operations along the coast of California from 1846-1847 during the Mexican-American War.

In 1939, Random House published the book, "Naval Sketches of the War in California,” featuring 28 reproductions from the original sketchbook. A limited-run publication, 1000 copies of the book were printed by the Grabhorn Press. In Franklin D. Roosevelt’s own words regarding his collection of Meyer’s works, written as the Introduction to the publication:

"He participated in many of the scenes depicted, and for the others had the privilege of discussion with eyewitnesses. There seems to have been no facile pen among the handful of bold, hard-bitten husky sailors, marines, soldiers and frontiersmen who won that empire for us. No doubt pen and paper were scarce in that primitive region. Complicated war operations scattered through a thousand miles of virgin coast and country gave little opportunity for writing or sketching. Thus the very dearth of adequate contemporary literature adds much to the historical value of Gunner Meyers’ brush.

In many years of collecting sketches, paintings and engravings relating to the Navy of the United States, I had found virtually none which had connection with naval operations in the Pacific in 1846 and 1847. When, therefore, I had the opportunity a few years ago of acquiring the original sketch-book of Gunner William H. Meyers, USN, I realized its historical value.

Not only do these sketches fill a definite gap in the history of this Nation and of our sister republic of Mexico, but they also throw an interesting light on the conduct of land and naval warfare less than a hundred years ago."

Join us throughout 2023 as we present #FDRtheCollector, featuring artifacts personally collected, purchased, or retained by Franklin Roosevelt, all from our Digital Artifact Collection: https://fdr.artifacts.archives.gov/objects/4885

#FDR the Collector#fdr#franklin d. roosevelt#museum from home#museum collection#combat art#combat artist#mexican american war#19th century

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Big Lit Meets the Mexican Americans: A Study in White Supremacy

HarperCollins tells us: “We publish content that presents a diversity of voices and speaks to the global community. We promote industry and company initiatives that represent people of all ethnicities, races, genders and gender identities, sexual orientations, ages, classes, religions, national origins and abilities.” The New York Times proclaims its dedication to building a “culture of inclusion,” while the University of Arizona’s MFA program commits itself “to proactively fostering diversity and inclusion throughout its curriculum, admissions, hiring, and day-to-day practices.”

Some of these statements may reflect actual practices while others are simply corporate boilerplate. Whether they are sincere or not, the fact remains that most books agented, sold, reviewed, and distributed are mostly written by white people and are, moreover, mostly agented, sold, reviewed, and distributed by other white people. (In fact, the term “diversity,” as used in such statements, seems to reinforce rather than confront the notion that white, cisgender people are the norm and everyone else is a big, indistinguishable mass of otherness. But that’s a different essay.)

Big Lit is virtually a whites-only country club. Everyone knows this. The lack of racial diversity among the people who populate Big Lit is an open secret. The Big Five — Penguin Random House, Hachette, Macmillan, Simon and Schuster, and HarperCollins — is still where it’s at in terms of getting maximum exposure, resources and mainstream acceptance. Big Lit can consign to near invisibility the work of entire communities of writers it decides not to take up.

This essay is a kind of case study of the Mexican-American literary community, a community whose writers Big Lit rarely takes up. But I don’t mean to offer another lecture about Big Lit’s lack of diversity (well, not entirely). Rather, I want to examine how the ideology of white supremacy works to brand an entire population of nonwhite people — here, Mexican Americans — as inherently inferior to whites, how that message is reinforced by means both legal and extra-legal, how it seeps into literary culture, and, how, ultimately, literary culture (i.e., Big Lit) consciously or unconsciously views this population through the lens of those white-supremacist beliefs.

This ingrained and complex racism can’t be ameliorated by platitudes about diversity or tokenistic representations of “diverse” populations.

Part One

When Donald Trump called Mexican immigrants “rapists” during the announcement of his 2016 presidential bid, he was strumming a very old chord in white America’s consciousness. Since the mid-19th century, the denigration of Mexicans and, by extension, Mexican Americans has been an ongoing project of white America. The pivotal point was the US invasion of 1848 and the forcible appropriation of half the territory that comprised the nascent Mexico. Then as now, Mexico saw the war for what it was: an unprovoked and unprincipled land grab. As a Mexican newspaper at the time thundered: “A government […] that starts a war without a legitimate motive is responsible for all its evils and horrors. The bloodshed, the grief of families, the pillaging, the destruction. […] Such is the case of the U.S. Government, for having initiated the unjust war it is waging against us today.”

Fueled by the almost religious conviction that the United States was destined to occupy the entire North American continent, Anglo America embarked on the near extermination of indigenous people and the conquest of Mexico. From the outset, Manifest Destiny was a racialist doctrine.

As one historian observes:

By 1850 the emphasis was on the American Anglo-Saxons as a separate, innately superior people who were destined to bring good government, commercial prosperity, and Christianity to the American continents and to the world. This was a superior race, and inferior races were doomed to subordinate status or extinction.

America’s true motives were laid bare in a contemporary North American periodical, the American Whig Review: “Mexico was poor, distracted, in anarchy and almost in ruins — what could she do to stay the hand of our power, to impede the march of our greatness? We were Anglo-Saxon Americans; it was our ‘destiny’ to possess and to rule this continent — we were bound to it.” (Mid-19th-century Mexico was a troubled, unstable polity but still: If your neighbor’s house is on fire, is the morally appropriate response to break in and steal everything of value you can lay your hands on?)

At the end of the war, over 100,000 Mexicans were trapped on what was now the American side of the border. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo guaranteed that these captive people would become naturalized American citizens, with all the rights and privileges thereof, and that their property rights would be respected. Those promises evaporated almost as soon as the ink was dry on the treaty. The promised enfranchisement, it turned out, was only federal, not state citizenship. This ploy allowed the states that were carved out of annexed territory to limit citizenship to something called “white Mexicans.” As for the property right guarantee, Mexican property owners became bankrupt in American courts when fighting off American predators and squatters who would trespass and forcefully stay on their private property.

Arising at the same time was Western genre fiction, emerging first in the form of dime novels. This genre provided the most popular and widely distributed representations of Mexicans and Mexican Americans from the mid-19th century well into the 20th. Its practitioners included writers like Zane Gray, O. Henry, and Stephen Crane, as well as countless pulp writers. Film and, later, television perpetuated these representations and gave them even wider currency. Central to the Western genre was the theme of Mexican racial inferiority, which these narratives used to justify the invasion and conquest of Mexico; indeed one author called it, "conquest fiction."

Much of early Western fiction originated or was set in Texas, always a hotbed of particularly virulent anti-Mexican sentiment. Mexico had initially welcomed Anglo settlement in Texas, but the Anglos who arrived tended to be slave-owning Southerners with reactionary views about the purported inferiority of darker-skinned people. Mexico abolished slavery in 1829. This contributed to the Anglo-led secession of Texas from Mexico and the founding of the Texas Republic; basically, the white Texans wanted to maintain slavery.

Their attitudes toward their erstwhile Mexican hosts was summed up by Texas patriot Stephan Austin, who on one occasion described Mexicans as a “mongrel Spanish-Indian and negro race,” and on another as “degraded and vile; the unfortunate race of Spaniard, Indian, and African is so blended that the worst qualities of each predominate.”

Antebellum pulp Westerns with titles like Mexico versus Texas, Bernard Lile: An Historical Romance, and Piney Woods Tavern; or, Sam Slick in Texas created a set of Mexican stereotypes that prevailed well into the 20th century, among them the lazy peon, the evil bandido, and the licentious señorita. In these works most Mexican males are “segregated into two distinctly inferior types: peon servants and mestizo bandidos. As “half-breeds,” the mestizo bandidos are “a cut above the peons,” but “have no moral scruples. […] When the American heroes finally ‘unmask’ these poseur gentlemen and expose their wickedness, they either kill them or hurl them back across the color line into ‘brownness’ and disgrace.” The distaff side is represented by “Mexican woman […] graced with voluptuous figures but burdened by loose moral principles.”

Higher-brow publications like The Atlantic and Scribner’s Magazine were no less derogatory. An 1899 article in The Atlantic entitled “The Greaser” portrayed its Mexican-American subject as “the mestizo, the Greaser, half-blood offspring of the marriage of antiquity and modernity.” A travel piece in an 1894 issue of Scribner’s Magazine described the borderland between Texas and Mexico as “The American Congo”; the piece is a veritable encyclopedia of racist stereotyping, including this Trumpian observation: “The Rio Grande Mexican is not a law-breaker in the American sense of the term; he has never known what law was and he does not care to learn; that’s all there is to it.”

These caricatures of Mexican Americans were amplified and even more widely distributed as early moviemakers discovered the appeal of Westerns. Mexicans were, once again, cast as the dark-skinned foils to upright Anglo heroes as summarized by an author:

[F]ilm titles and advertising made open use of the word greaser, at least up to the 1920’s: The Greaser’s Gauntlet, The Girl and the Greaser, Broncho Bill and the Greaser, The Greaser’s Revenge, Guns and Greasers, or, bluntly, The Greasers. The artistic and cultural sensitivity of these films match their titles. If adventure stories, they feature no-holds-barred struggles between good Americans and bad Mexicans. The cause of the conflict is often vaguely defined. Some greasers meet their fate because they are greasers. Others are on the wrong side of the law. Others violate Saxon moral codes. All of them rob, assault, kidnap, and murder with the same wild abandon as their dime-novel counterparts.

These silent-era representations continued into the talkies.

Brownness, stupidity, laziness, cowardice, lawlessness, and sexual immortality: these became the signifiers of Mexicans in white America’s consciousness, reinforcing the notion that Mexicans are inferior to white people. This inferiority was race-based — that is, Mexicans were presumed to be inherently and in some inchoate sense biologically less intelligent, capable, and moral than white people.So deeply embedded are these cultural images that, after the death of the Western as a popular genre in books, movies, and TV, they simply shape-shifted into more contemporary versions.

Instead of the bandidos of yore, Mexican-American men transformed into gangbangers and drug dealers; the lazy peons became grocery-cart-pushing homeless people and hapless drug addicts; the flashing-eyed señoritas now tottered around suggestively on Fuck Me Pumps uttering heavily accented malapropisms. Often, however, these stereotypes don’t speak at all. In movies and on TV, you see brown people silently pushing laundry carts, pruning rose bushes, or stacking dishes into an industrial dishwasher, a sepia background against which the whiteness — and, thus, the superiority — of the real heroes and heroines gleams all the more brightly.

Part Two

Before Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, there was Mendez v. Westminster in 1946, the first federal court decision striking down school segregation. Let me explain.

California’s Orange County had set up “Mexican schools,” which all children of Mexican descent were required to attend from first to fourth grade. The ostensible reason was that they couldn’t speak English, but all Mexican-American children were forced into these schools regardless of their fluency. By the time the Mendez and five other families sued, these schools had 5,000 students. In the then-prevalent racial binary of black versus white, Mexicans were grudgingly considered “white.” This meant the plaintiffs couldn’t allege racial discrimination. Instead, they argued that the segregation of public schools impermissibly discriminated against their children based on ancestry and presumptive language deficiency.

In short, Orange Country’s segregation scheme wasn’t authorized by state law; thus, by extension, neither were other forms of segregation imposed on Mexican Americans in California by a comprehensive set of statewide Jim Crow–like laws. To summarize the situation: By the 1920s, many Southern California communities had established ‘Mexican schools’ along with segregated public swimming pools, movie theaters, and restaurants.” (On a personal note, I can testify that my mother remembers being turned away from a Sacramento public swimming pool sometime in the late 1940s because she was — and is — undeniably mestiza in appearance.)

From the mid-19th to the mid-20th centuries, whites used a combination of discriminatory legal and terroristic extra-legal tactics against Mexican Americans. Mexican Americans were disenfranchised, faced residential and education segregation, were denied the use of public facilities, and were in danger of being lynched. Yes, lynched — 571 ethnic Mexicans were lynched between 1848 and 1928; in addition, the Texas Rangers summarily executed at least another 500 Mexicans without trial.

As has repeatedly been the case, these discriminatory legal measures and extra-judicial assaults corresponded to high tides of Mexican immigration. In this time of history, Mexican immigration was between 1900 and 1930 - many, like my great-grandparents, refugees. Nativist whites such as Madison Grant, author of the influential The Passing of the Great Race, deplored this invasion by a “mongrel race.” White America’s attitudes toward Mexican immigration have always been both exploitative and ambivalent. On the one hand, these immigrants are useful because they serve as a cheap source of agricultural labor in the West; however, because they are members of an inferior “mongrel race,” they have to be closely monitored and firmly kept in place.

The ease with which bare tolerance could shift to active hostility was dramatically illustrated during the Great Depression. During this period, an estimated 400,000 Mexican Americans, 60 percent of them American citizens by birth or by naturalization, were forcibly repatriated to Mexico. The pretexts given were that Mexican Americans were taking scarce jobs away from white Americans and were a drain on government relief assistance. (Sound familiar?)

In a frenzy of anti-Mexican hysteria, wholesale punitive measures were proposed and taken by government officials at the federal, state, and local levels. Laws were passed depriving Mexicans of jobs in the public and private sectors. Immigration and deportation laws were enacted to restrict emigration and hasten the departure of those already here. Contributing to the brutalizing experience were the mass deportation roundups and reparation drives. […] An incessant cry of “get rid of the Mexicans” swept the country.

Mexican Americans never passively consented to their victimization by white Americans. Following the end of the Mexican-American War, they fought the unlawful seizure of lands guaranteed to them under the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in American courts many being unsuccessful and losing their private property and homes to Americans who illegally squatted on their land and protested the decisions by California, Texas, and Arizona to limit citizenship to “white Mexicans.” In the 1930s, long before the establishment of the United Farm Workers, Mexican agricultural workers organized themselves into unions and went on strike in California, Arizona, Idaho, Washington, and Colorado; they were met with brutal suppression. “[w]ith scarcely an exception, every strike in which Mexicans participated in the borderlands in the thirties was broken by the use of violence and followed by deportations. In most of these strikes, Mexican workers stood alone, that is, they were not supported by organized labor.”

The 1960s and ’70s saw the birth of the Chicano Movement — emphasizing racial pride and resistance to racism. That movement also gave birth to a body of literature that is now acknowledged to contain many of the ur-texts that form the basis of Chicano/a and Latinx studies programs.

And now? Who are these Mexican Americans? While their numbers continued to be greatest in the western states, there are Mexican-American communities in every state in the union, with a significant presence in the Midwest and a growing presence in the South. In contrast to the aging white population, a 2007 survey revealed only six percent of “Hispanic Americans” to be 65 or older; the comparable percentage for whites was 15 percent. Thus, a brown workforce increasingly supports white retirees.

Contrary to the stereotype that most Americans of Mexican descent are recent immigrants, the majority of Mexican Americans are native-born. That percentage will only increase because Mexican immigration — even before Obama’s massive deportations and Trump’s war against immigrants — has been steadily decreasing, as a 2015 Pew Research Poll shows. That poll also dispels another stereotype, showing that almost 90 percent of native-born Mexican Americans are proficient in English. Moreover, Pew Research has also established that 83 percent of all Latinos and 91 percent of Latino millennials (including, of course, Mexican Americans) get their news in English.

The Department of Education reported a 126 percent jump in Latino students entering college between 2000 and 2015.

In short, Mexican Americans comprise a youthful, increasingly well-educated, largely native-born and English-proficient, aspirational community.

Yet, despite all this, Mexican-American representation in mainstream American culture, when it appears at all, remains either tokenistic, stereotypical, or both. In film, television, and books this emergent community is still largely ignored.

Part Thee

As part of my research for this essay, I looked at the course syllabi for a half-dozen courses in Latinx or Chicano literature from colleges across the nation, in order to see which Mexican-American works and writers scholars deem canonical. This is the list I came up with (virtually all these books were taught at more than one school):

Americo Paredes, George Washington Gómez (written in mid-’30s; published 1990)

Tomás Rivera, … y no se lo tragó la tierra/and the earth did not devour him (1971)

Rudolfo Anaya, Bless Me, Ultima (1972)

Sandra Cisneros, The House on Mango Street (1984)

Arturo Islas, The Rain God (1984)

Ana Castillo, The Mixquiahuala Letters (1986)

Gloria Anzaldúa, Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza (1987)

Alejandro Morales, The Rag Doll Plagues (1991)

Helena Maria Viramontes, Under the Feet of Jesus (1995)

Norma Elia Cantú, Canícula (1995)

Reyna Grande, Across a Hundred Mountains (2006)

What most of these books have in common is that, with two exceptions, none were published by the Big Five or their predecessors; instead, almost all were originally published by small presses. While some were later picked up by Big Five publishers for paperback editions, most are still being kept in print by independent or university presses. Even The House on Mango Street, now generally recognized as a classic work of American fiction was originally published by Arte Público Press.

What this illustrates is Big Lit’s long history of ignorance or indifference to Mexican-American writers and the Mexican-American experience in this country. Yet to read any of these books is to experience a vision of America at once unique and familiar, for each in its own way tells a quintessentially American story. It’s just not a white American story. Yet very few Mexican-American writers find a place in Big Lit.

Big Lit is a very, very white place. White people overwhelmingly populate the Big Five; as the now-famous publishing diversity study by Lee & Low Books reported, 79 percent of people employed in the industry in 2015 were white and only six percent Latino.

A 2019 salary survey of the publishing industry undertaken by Publishers Weekly put the percentage of white employees at 84 percent.

Librarians, who are crucial to the sale and dissemination of literary texts, are also overwhelmingly white. A February 2013 editorial in The Library Journal entitled “Diversity Never Happens” observed that “Hispanics are some of the strongest supporters of libraries, and yet they continue to be thinly represented among the ranks of librarians.” ”The editorial cites statistics showing that, while Latinos/as are more likely to use libraries on a monthly basis than whites, only eight percent of the 118,666 credentialled librarians were Latino/a. A 2017 statistical study reports that “89 percent of librarians in leadership or administration roles were white and non-Hispanic.”

Similar demographic information for other realms of Big Lit appears to be unavailable. No one seems to be keeping any record of what percentage of the writers who are reviewed — or the reviewers who review — in The New York Times Book Review, Publishers Weekly, or Booklist, for example, are white. In a 2012 study of book reviews published by The New York Times, it was found that 90 percent of the books reviewed in 2011 were by white writers. White writers are vastly and disproportionately overrepresented both as reviewers and subjects of reviews in comparison to writers of color.

There are over 1,300 literary agents in the United States, most of them in New York, but I could find no statistics about their racial demographics. I did find an anecdotal study from the late 1990s, in an article called “Dearth of Hispanic Literary Agents Frustrates Writers.” The asserted that neither the literary agencies canvassed in The Literary Market Place nor the roster of agents in the Association of Authors’ Representatives listed a single Latino/a agent. The number is now likely greater than zero, but I have no doubt that the profession remains at least as white as publishing.

Similarly, there are, to my knowledge, no statistics about the racial composition of students and faculty at the many MFA programs around the country. There are, however, plenty of anecdotal accounts of how students of color are received in these programs. The essay “The Student of Color in the Typical MFA Program” powerfully summarizes these experiences. According to the essay, if a student of color objects to a racist depiction in a work by a white student, she or he risks being accused of censorship, or else the objection is dismissed as a political argument outside the bounds of literary analysis. Moreover, the student’s objection often triggers guilt or anger in white students and teachers because it challenges their cherished beliefs that they are not racist, and so they respond by branding their colleague a troublemaker.

The whiteness of Big Lit has practical consequences for Mexican-American writers. If virtually every agent, editor, book reviewer, and librarian is white, then such writers will have a much harder time finding representation, getting published, being reviewed and recommended. Therefore, there will be fewer Mexican-American voices in the literary culture. And this, in turn, means that there will be fewer counterbalances to the racist depictions of Mexican Americans in mainstream culture — portrayals that allow Trump and other white supremacists to continue to vilify a large segment of the American population.

White progressives in Big Lit may lament this situation, but they take no responsibility for the perpetuation of white privilege, if not white supremacy, in literary culture. Why? Because that privilege benefits them.

Part Four

The obvious issue is this: the white people who make up Big Lit live in a culture whose history and practice enshrines the belief that Mexican Americans are inherently inferior to whites, and fundamentally they’re okay with that.

The standard American university education continues to emphasize the primacy of white writers and their experience. To achieve a literary culture that truly reflects America’s multiracial society first requires an acknowledgment that Big Lit’s views regarding the putative universality of white experience are rooted in the ideology of white supremacy.

Other commentators have noted that the Big Five apply a double standard when acquiring and retaining writers of color. Writers of color aren’t allowed to fail the same way white writers are allowed to. If one book by a white author doesn’t sell, no one at the publishing house says they shouldn’t acquire any books by white authors the next season. But if a book by a Mexican, for example, doesn’t sell, the publisher may take its sweet time in “taking a risk” on another.

But aren’t disappointing sales a good reason to not continue publishing a particular writer or kind of book? That would be an acceptable explanation if the same standard applied across the board. To amplify the point above, however, if a white novelist from Brooklyn fails to make back her advance, that doesn’t mean her publisher won’t acquire other white Brooklyn novelists or even refuse to publish that particular author’s next book. Moreover, and here’s where the argument really falls apart, most books fail to make money, at least initially. The editor-in-chief at One World noted at the LARB/USC publishing workshop in July 2019 that 10 percent of books published by the Big Five support the remaining 90 percent. If most books are a risk, why is that risk disproportionately attributed to work by writers of color?

“Hispanics don’t read.” Whether a Big Five editor ever actually uttered those words, it is widely believed by the Latino/a community to be a sentiment Big Lit harbors about us. According to a nationally syndicated columnist after a day or two after a book's release, she got a call from a New York Times reporter asking her how well the book would sell. The reporter jumped in to the first question: ‘Why don’t Latinos read?’”

The Big Five, like the larger media culture, are not representative of the U.S. but of the limited tastes of the elite of Manhattan and certain areas of Brooklyn. These cultural gatekeepers — publishers, editors, agents — are simply unfamiliar with Latinos. A bias seeps into their decision making, based again on the unwarranted assumption that Latinos don’t read.

The notion that Mexican Americans and other Latinos/as don’t read is clearly rooted in assumptions of racial inferiority — e.g., immigrant, poor, less educated, less intelligent.

In short, the ideology of white supremacy is at the root of Big Lit’s “diversity problem.” The reason Big Lit doesn’t seek out, encourage, publish, and promote Mexican-Americans writers is because the people who work in it don’t really believe that Mexican Americans are the intellectual or creative equals of — or that their stories have the same value as those of — white writers.

Hey Big Lit: You think the Mexican-American experience can be expressed in a handful of stereotypes, most of which emphasize the intellectual and moral inferiority of Mexican Americans. While we’ve had to figure out white people, you’ve never had to think past your stereotypes of us. While we’ve been paddling upstream against the current of your white-supremacist assumptions, you’ve been lazily drifting along in them. You know nothing of our historical experience, while all of us have had the false narrative of white American triumphalism forced down our throats. And while you mouth your support for “diversity,” any such initiatives that you control will be, at best, tokenistic. Indeed, the concept of “diversity” itself may simply be an attempt on your part to deflect attention away from white-supremacist assumptions by turning the issue of race into a discussion about mere representation.

There can be no real diversity without a real and meaningful redistribution of power.

It’s almost impossible to imagine that the white people who compose somewhere north of 79 percent of Big Lit would ever voluntarily and actively agree to — and work toward — an industry where their percentage slipped below 50 percent. When it comes right down to it, Big Lit, you’re much more invested in maintaining your privilege, and passing it down to your white heirs, than in helping to create a literary culture that genuinely represents the fullness of the American project — warts, near-genocides, invasions, lynchings, and all.

Of course, we’ll keep on calling you out, because you do respond sometimes — out of guilt, if nothing else. Maybe you’ll publish a few more Mexican-American writers, review a book or two about the Mexican-Americans experience, hire a Mexican-American writer to teach in your MFA program, highlight the works of Mexican Americans in your bookstore when it’s not “Hispanic Heritage Month.” We will also will continue to remind you that you will find yourself listed among the collaborators, right up there with the Scribner’s Magazine editor who commissioned “The American Congo.”

Source

#🇲🇽#usa#united states#racism#discrimination against Mexicans#imperialism#colonization#colonialism#history#mexican history#mexico#mexican american war#remember the alamo#texas#movies#books#representation#tv shows#segregation#Mendez v. Westminster #california#lynching#texas rangers#white supremacy#eugenics#immigration#mexican revolutiom#great depression#arizona#idaho

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's September 13th. On this day in 1847, six Mexican military cadets died in the defense of Mexico City during the Battle of Chapultepec, one of the last major battles of the Mexican–American War. At the time of the US invasion in 1846, Chapultepec Castle served as the Mexican Military Academy. Its troops and cadets were commanded by General Nicolás Bravo. On this day, the castle's 800 Mexican defenders included between 47 and a few hundred cadets. They were greatly outnumbered by General Winfield Scott's 7,000 troops. After about two hours of fighting, General Bravo ordered retreat, but six cadets refused to fall back and fought to the death. Legend has it that the last of the six, Juan Escutia, leapt from the castle wrapped in the Mexican flag to prevent the enemy from capturing it. The day of their martyrdom is now celebrated in Mexico as a civic holiday to honor the cadets' sacrifice.

In 1947, US President Harry S. Truman placed a wreath at the Obelisco a los Niños Héroes, a monument in Mexico City commemorating the cadets, and stood for a moment in silent reverence. Asked by American reporters why he had gone to the monument, Truman said, "Brave men don't belong to any one country. I respect bravery wherever I see it."

The result of the war was that Mexico lost almost half of its territory to the US. However, Mexico's language and culture has lived on in the seized lands and has even expanded beyond. ☮️ Peace… Jamiese of Pixoplanet

#heroes#bravery#brave#courage#courageous#mexico#mexico city#ciudad de mexico#mexican American war#chapultepec#juanescutia#escutia#mexican culture#mexican food#mexican music#mexican fashion#mexican american#mexicana#harry truman#castillo de chapultepec#chapultepec castle#winfield scott#nicholas bravo#dia de los ninos heroes#obelisco a los ninos heroes#military academy#treaty of Guadalupe hidalgo#espanol#jamiese#pixoplanet

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

BOOK REVIEW: VAMPIRES OF EL NORTE BY ISABEL CANAS

⭐⭐⭐

I went into this book looking forward not only to reading a genre I don’t normally read but because, based on the synopsis and what I knew about the book, it would also utilize elements of other genres I enjoy. While I loved the story and enjoyed reading the book, for me, it felt very mid.

It gave us little tastes of the horror and romance plotlines, but I don’t think we ever got quite enough for them to make an impact. The “vampires” had interesting lore when it was finally shared, but otherwise, we know very little of them. Usually, I’m okay with some intrigue, but here it just worked against the narrative. It almost felt like the book didn’t think the reader was smart enough to handle knowing more about them. When we did have a really cool and kinda freaky reveal about the vampires, I was hoping we’d get more and it would lean into its vampire horror label, but both the story and characters just played it off, which was disappointing.

The romance between Nena and Néstor just didn’t pack the punch I think it intended to. There was some character growth, which I always love, but it all happened a little too late to impact the story in a more meaningful way. I am happy with their ending, but I didn’t find myself rooting for them until the very end of the story, despite how their dynamic is set up initially.

What I enjoyed the most in this book was the historical fiction aspect and the writing style. I truly felt like I was experiencing several action-packed sequences alongside the characters and that I was being introduced to a different side of history. Many scenes played out cinematically in my head and I credit the writing style for that. I think this could make a visually stunning movie based on the writing alone.

#book review#book reviewer#2024 reviews#historical fiction#vampire horror#horror story#horror writing#vampire#vampire story#mexican american war

0 notes

Text

got to teach my husband about californian history and why the legend of zorro (2005) was a travesty

if you don't understand why, here, have the first sentence of the film description!

"A secret society, the Knights of Aragon, seeks to keep the United States from achieving manifest destiny -- and only the legendary Zorro (Antonio Banderas) can stop them."

#zorro#legend of zorro#the legend of zorro#the legend of zorro (2005)#antonio banderas#mexican american war#manifest destiny#he literally was like everybody quick vote to join the us#such a betrayal#folk heroes#hollywood#us imperialism#i love you goodnight

1 note

·

View note

Text

everytime i tell europeans my favorite cuisine is texmex & sonoran they are like “American bastardized Mexican food?” and i feel like im going insane. its not bastardized. its their fucking cuisine.

#never spoke to a tejano person in their life#im left to the task of explaining the mexican american war#as well as the texas independance#and how the border moved not the mexicans#and that their food with be shaped by a different geopolitical context#they get bored quickly#but i will defend the chimichanga

46K notes

·

View notes

Text

A United States Treasure: The History, Ecology, and Preservation of the Uintah Basin

“The more clearly we can focus our attention on the wonders and realities of the universe about us, the less taste we shall have for destruction.”― Rachel Carson

Ecology is an essential field of study that explores the relationships between living organisms and their environment. It is crucial for understanding how our natural world works and how we can maintain its balance. Ecology plays a…

View On WordPress

#earth#ecology#environmental science#history#mexican american war#nature#philosophy#preservation#science#skinwalker ranch#uintah basin#united states#united states history

0 notes

Text

last annual meeting of the Texas Veterans Association (1906)

#texas veterans association#texas#lone star republic#mexican american war#united states of america#history

0 notes

Text

Favorite thing is when historica figures hate other historical figures and things they did not because they did bad things ( which they still did ), but because of completely other things that they did that weren't even all that bad/important in the large scheme and to everyone else AND YET-

ex:

Daniel Webster hating Taney not because he's a fucking racist, but because he hates corporations and JOHN MARSHALL didn't hate corporations, and JOHN MARSHALL actually listened to my arguements, you little Jacksonian dipshit!

#daniel webster#john marshall#roger taney#andrew jackson#john c calhoun#james k polk#mexican american war

1 note

·

View note

Photo

In 1847, after landing at Veracruz, Winfield Scott orders a continent of marines to threaten the Tehuantepec Route, a strategic territory that served as an overland rout for good moving between the Atlantic and Pacific without the risk of traveling around Cape Horn. The war ends before the Marines can actually land, but port is shelled and blockaded by a few US naval vessels. Rumors abound in Mexico City and the Mexicans are willing to offer the Americans anything to abandon claim to such a vital part of their economy. The "Anything" in question is the inclusion of the Baja peninsula in the annexation of Mexican territory.

At the domestic negotiations around the admission of California and Texas to the Union, the parties get hyperfixated on the appropriate borders for the new states, especially now that the southern most point of the Untied States, the fishing village of Cabo San Lucas is over 800 nautical miles south of the Missouri Compromise line. After weeks of debate, California and Texas are admitted far smaller than they were in OTL, with far more territories drafted to be potential slave or free states per the terms of the Compromise of 1850. Texas and California are annoyed at this decision, but as their borders reflect the centers of population in 1850, nothing grows beyond minor grumbling.

By 1859 Colorado is petitioning for admission as a slave state, while Matagorda seeks admission as a free state. The chaos this causes in Congress carries over into the election of 1860 and the secession crisis itself. The Confederacy did not recognize Matagorda as a state, while the Union did. Colorado was a political nightmare because the Lincoln administration maintained that no states were actually in rebellion because secession was illegal to begin with, thus Colorado's right to enter the Union had to be respected... but would be delayed. This was made all the more complicated when The Army of Colorado was formed by J.P. Gillis and moved against Union forces in southern Colorado, what would later become Cabrillo.

Matagorda by comparison proved to be a boon for the Union, as it was quickly made an anchor point for the Anaconda plan, and hastened Texas's encirclement and capture by the Union. The state also had a sizable cotton industry of its own, and further complicated the Confederates' negotiations with the British.

Post-war, Colorado's admission to the Union was routinely delayed, and the unrecognized state was made the center of the 6th Military District which encompassed the Confederate claimed territories of the Southwest. This district was reduced to Colorado's modern borders within a year, and by all accounts was only created so the Republicans could show rapid progress for restoring the Union. Cabrillo would finally become a state in 1870, just after Georgia was re-admitted to the Union. The state was only accepted after Mariposa was similarly admitted as a state, as it was largely populated by Republicans.

As time passed, the states of the Southwest were slowly admitted to the Union, with Mojave being the last state in the contiguous United States to be admitted in 1914. As history marched along, the West Coast remained a Republican stronghold for the most part, with the exception of Colorado, largely due to its population of former Confederates who saw the state as "their piece" of the Golden West. After World War II, the population of the Pacific states exploded, with the Pacific Southwest seeing some of the largest growth in the country, a good deal of it from immigration via Mexico. As a result, it eventually became a common observation that winning the West Coast in an election would mean you'd win the White House and the Senate. The weight of the more urbanized states of the Northeast and West Coast, has bred a great deal of animosity among the country's more rural states, who've increasingly thrown their weight behind a string of third party candidates while the Democrats and Republicans fight for the support of the places where everyone actually lives.

Thanks to all my Patreon supporters who made this map possible. All my patrons get early access to my projects before they go live. Please subscribe at: patreon.com/SeanMcKnight

#Alternate History#alternate universe#map#cartography#texas#california#civil war#mexican american war

1 note

·

View note

Text

Pasadena and Galveston Ramblings

Pasadena and Galveston Ramblings

It took a visit to family in Pasadena with my mom and sister. While there, we saw wonderful things in Pasadena and Galveston that the area has to offer. Family settled in the area so most of our visit was focused on kinfolk. But we made time for a bit of touring.

My sister found an air B&B for our stay so the three of us settled into the house. With each of us in our own rooms we had plenty of…

View On WordPress

#Armand Bayou Hike and Bike Trail#Bishop Christopher E. Byrne#Engels on Edwards#family time#Galveston#Galveston Historical Foundation#Lone Star State#Mexican American War#Morning Kolaches#Pasadena#President Antonios Santa Anna#Sacred Heart Church#Sam Houston#San Jacinto Battle Monument and Museum#spurs#Sunflower Bakery & Cafe#The Moody Mansion

0 notes