#river basins

Photo

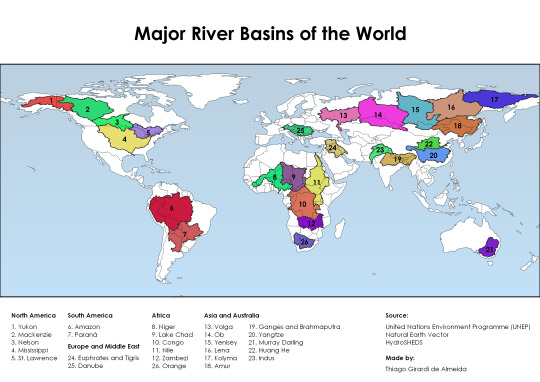

The 26 major river basins of the world

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

River basin map of Tanzania. Colours represent different catchment areas.

Read more and buy prints here.

Ko-fi | RedBubble | Etsy (digital prints)

#tanzania#africa#rivers#river basins#watersheds#watershed map#map#maps#mapping#geography#cartography#artists on tumblr#independent artist#my art

112 notes

·

View notes

Text

To safeguard our future, we must unite in action.

The air we breathe, the water we drink, the food on our tables, the medicines that heal us, the livelihoods we depend on — are all provided by Earth's ecosystems, on which humanity’s survival depends. UN Environment programme.

Follow the conversation witg the hashtags #ForNature.

#fornature#united nations environment programme#water resources#river basins#rivers#water bodies#take action#clean river

0 notes

Text

#Legend of Mana#Seiken densetsu 4#Lom#Legend of mana remake#Switch#Nintendo switch#Remaster#Waterfall#Natural bridge#Basin#River#Stream#Waves#Cascade#Cataract#Mine

140 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Following these small lakes, the source of Pinnacles Creek which feeds into Piute Creek, which feeds into the San Joaquin River, which flows to the San Francisco Bay. John Muir Wilderness, Sierra Nevada Mountains, California, USA. Photo by Van Miller

#pinnacles lakes basin#san joaquin river#Piute Creek#san franciso bay#san francisco#hiking#backpacking#camping#john muir wilderness#Sierra Nevada Mountains#california#©Van Miller#photography#travel#Wanderlust#geology#lakes#mountains#Wilderness#the wilderness journals

218 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Landing over the Potomac

Shot on Cinestill 800T

#cinestill 800t#potomac river#southwest#dc#plane#film photography#tidal basin#long exposure#film#light trails#washington#february#around dc#my work#photography

172 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anaconda, Queen of the Amazon.

#vintage illustration#snakes#anaconda#the amazon#south america#jungles#south american jungle#amazon basin#amazon river#eunectes murinus#herpetology#biology#zoology

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

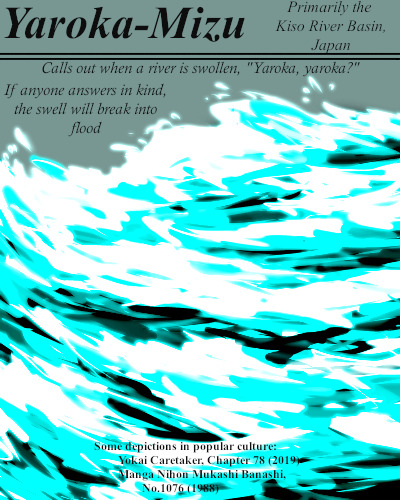

To respond in kind to the invisible Yaroka-Mizu's call is folly. Roughly translated, they ask "Do you want some?" Of course if one affirms with an answer they will give it all.

#BriefBestiary#bestiary#digital art#fantasy#folklore#legend#monster#yokai#river monster#invisible#youkai#yaroka-mizu#yaroka mizu#kiso river basin#japanese folklore#japanese legend#flood#river yokai#flood yokai

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

How solar power is changing life in Ecuador's Amazon basin

For more than 40 years, the local Indigenous people, the Achuar, have been advocating to stop oil development, which has ravaged large swaths of the Ecuadorian Amazon. But even as they fought against fossil fuels, gasoline was their only option to light their homes and power the boats tied to their livelihood. This area has the thinnest electric coverage in the country. But now a smattering of solar panels across 12 villages in a couple of Ecuador’s deeply forested eastern provinces are transforming life.

Solar power is shaping how they go about daily life in ways big and small, from how they get to work to how they negotiate their connections to the world beyond the Amazon.

Photo above: A solar-powered electric boat

For generations, young men farmed the land, built huts or left their village to find work outside the jungle. Now solar panels are opening up other options.

In the Kapawi Solar Center, an open structure overlooking the Pastaza River, 20 solar panels power a dozen outlets strapped to bamboo poles. There, technicians such as Óscar Mukucham can charge up and hold workshops on how to install panels.

As a boy, Mukucham, now 23, had visions of solar boats moving through the river. Now he teaches others how to maintain them in the Amazon humidity.

Solar power is also fueling eco-tourism. The Kapawi Ecolodge, a hotel managed by the community, boasts 64 panels that illuminate 10 cabins, the dining room and other hotel facilities for 24 hours a day.

The solar boats are so quiet, they make for ideal vessels for nature tours: They don’t scare away dolphins or birds.

For Canelos, the lamps and panels are enabling a bigger vision: powering the Amazon without scarring it with roads and poles. Solar energy connects them to the world beyond their home, while preserving the ancient traditions that have sprouted from its rich rainforest floor.

“We cannot talk about the fight against extractive activities if we are consuming fuel,” he said. “Just as the sun makes life possible on the planet, it also allows the Achuar to keep their culture alive.”

Source

#ecuador#amazon river#amazon basin#rural#solar power#solar power boats#solar farms#clean energy#transformation#latin america#indigenous peoples

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

New batch of bisque fired children, ready for glazing before final firing. I'm really enjoying working with this new clay, called Fool's Gold, that when fired to cone 6 will be a speckly golden color with tiny black flecks. Bisque fired it looks kinda pink!

#fossils#dinosaur#paleoart#archaeopteryx#salamander#lizard#it's a fossil from the Green River Basin and I have the details on my laptop lol#quince#ikebana#flowering quince#eastern tiger swallowtail butterfly#butterfly#ceramics#pottery#flower pots#wip#jurassicqueer original post#my art#artists on tumblr

108 notes

·

View notes

Text

Excerpt from this story from the New York Times:

There’s a struggle for law and order in many of the world’s tropical forests, and nature is losing.

Last week, I wrote about the major progress Colombia made in 2023, slashing deforestation rates by 49 percent in a single year. But this week, we learned the trend reversed significantly in the first quarter of this year. Preliminary figures show tree loss was up 40 percent since the start of the year, Colombia’s Minister of Environment, Susana Muhamad, told reporters on Monday.

Why have things changed so quickly? Mostly because a single armed group controls much of Colombia’s rainforests.

Muhamad explained that conflicts with Estado Mayor Central, a group that is thought to run a sprawling cocaine operation among other illegal activities, were partly behind the striking numbers. “In this case, nature is being placed in the middle of the conflict,” she said. According to experts, E.M.C. had largely banned deforestation and in recent months it seems to have allowed it again.

A 2023 United Nations report referred to this entanglement between drug trafficking and environmental crime as “narco-deforestation.” Perhaps nowhere is that phenomenon more clear than in Colombia, a country that’s both a stage for the decades-old global war on drugs and one of the most biodiverse corners of the planet, where the Andes Mountains meet the vast Amazon rainforest.

But what’s happening in Colombia underscores a growing challenge for many developing countries. Vast pristine forests are both essential to curb climate change and biodiversity loss, and they’re also prized by groups who want to hide illegal activities beneath thick tree canopies.

Today I want to explain why experts on the ground say that there’s no way to protect crucial forests like the Amazon without dealing with the growing power of armed groups.

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The 5 Largest River Basins

280 notes

·

View notes

Text

River basin map of the Americas. Colours represent different catchment areas.

Read more and buy prints here.

Ko-fi | RedBubble | Etsy (digital prints)

#geography#maps#cartography#my art#artists on tumblr#digital art#river map#map making#wall art#independent artist#the americas#american rivers#watersheds#watershed map#river basins#river basin map

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

4th Meeting, Global Workshop on Droughts in Trans-boundary Basins.

The global workshop will bring together water, agriculture, climate and environment communities as well as drought experts to jointly discuss best practices and lessons learned in addressing droughts in transboundary basins.

Watch the 4th Meeting, Global Workshop on Droughts in Transboundary Basins.

#droughts#rivers#Panel Discussion#lesson learnt#workshops#waterways#river basins#river's ecosystems#water governance

0 notes

Text

Above: Lidar-derived image of the Neches River in east Texas, U.S.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Biden administration agreed Thursday to spend more than $200 million to fully fund Native tribes’ plans to reintroduce salmon in the upper Columbia River basin — more than 80 years after construction of the Grand Coulee Dam rendered the fish extinct in parts of Washington, Idaho and British Columbia.

The unprecedented show of federal support is a course correction from the previous efforts of some federal agencies to resist tribal salmon restoration, which were documented in an August 2022 investigation by Oregon Public Broadcasting and ProPublica.

“This agreement is the start of fixing a wrong,” Greg Abrahamson, chair of the Spokane Tribe of Indians, said during the announcement of the agreement. “Grand Coulee Dam allowed the desert to bloom, and many faraway cities enjoyed the cheap electricity it produces, at my people’s expense.”

The announcement is also a recognition of the federal government’s long-standing violations of the fishing rights of sovereign tribes, some of whom have signed treaties with the U.S. government. Construction of Grand Coulee Dam destroyed the Columbia River fishing site of Kettle Falls, a regional trading hub and sacred site for many salmon-dependent tribes. It cut off hundreds of miles of river habitat for salmon, who migrate to the ocean as young fish and return to their home waters to spawn as adults. Salmon and other oceangoing fish once accounted for an estimated 60% of the historic diet for Northwest Indigenous people. After the construction of Grand Coulee and other dams in the upper Columbia basin, those fish disappeared.

After nearly 80 years without those fish, a coalition of tribes along the upper Columbia River developed in 2015 a multiphase plan to reintroduce salmon into areas where they’d been blocked.

The tribes’ long-term plan involves building hatcheries, releasing fish into waters above Grand Coulee, tracking their migration and developing plans to pass fish safely around the dams through techniques like trapping them and trucking them up or downstream. They designed the plan to ensure it does not interfere with hydropower generation at the federal government’s biggest dam on the Columbia.

27 notes

·

View notes